Abstract

The emergence of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV‐2), the agent of novel coronavirus 2019 (COVID‐19), has kept the globe in disquiets due to its severe life‐threatening conditions. The most common symptoms of COVID‐19 are fever, sore throat, and shortness of breath. According to the anecdotal reports from the health care workers, it has been suggested that the virus could reach the brain and can cause anosmia, hyposmia, hypogeusia, and hypopsia. Once the SARS‐CoV‐2 has entered the central nervous system (CNS), it can either exit in an inactive form in the tissues or may lead to neuroinflammation. Here, we aim to discuss the chronic infection of the olfactory bulb region of the brain by SARS‐CoV‐2 and how this could affect the nearby residing neurons in the host. We further review the probable cellular mechanism and activation of the microglia 1 phenotype possibly leading to various neurodegenerative disorders. In conclusion, SARS‐CoV‐2 might probably infect the olfactory bulb neuron enervating the nasal epithelium accessing the CNS and might cause neurodegenerative diseases in the future.

Keywords: COVID‐19, neurodegenerative disorders, neuroinflammation, olfactory bulb dysfunction, SARS‐CoV‐2 neuroinvasion

Abbreviations

- AD

Alzheimer's disease

- CNS

central nervous system

- M1

microglia 1

- PD

Parkinson's disease

- SARS‐CoV‐2

severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

- TNF‐α

tumour necrosis factor‐α

1. INTRODUCTION

The novel pandemic coronavirus 2019 (COVID‐19) has expanded at an unprecedented rate around the globe where the researchers are striving to find a cure for this pandemic. This shattering viral infection has infected around 10.5 million people with a death toll of over five hundred thousand as of July, 2020. At this time, it is imperative to understand the possible connections between COVID‐19 and other detrimental illnesses (Balachandar et al., 2020). The COVID‐19 is highly prevalent in human and has the prospect to reach the brain without evident clinical symptoms. The central nervous system (CNS), a prodigy of convoluted cellular and molecular interactions, maintains life and orchestrates homoeostasis. Unfortunately, if there is any acute, tenacious or dormant form of viral infection inside the CNS, its immune system does not react subsequently, which results in neurological disorders. The severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV‐2) infection has created chaos due to its possible ability of neuronal invasion, which might have a long‐term effect on the affected patients in their future. Also, the study highlights that the mechanism or route of transmissions of the neuroinvasive property of SARS‐CoV‐2 remains scarce (Koralnik & Tyler, 2020; Li, Bai, & Hashikawa, 2020). Such type of neuroinvasive propensity of coronaviruses has been documented in most of its beta‐coronavirus form, including SARS‐CoV, MERS‐CoV, HCoV‐229E, and SARS‐CoV‐2 (Vellingiri et al., 2020). A study has indicated that, through this viral neuroinvasion, the SARS‐CoV‐N protein can invade various other organs such as the stomach, small intestine, kidney, sweat glands, parathyroid, pituitary gland and liver, resulting into multiorgan failure in human beings (Ding et al., 2004). While dealing with the aftermath of this pandemic, it is important to carefully consider the potential effects of SARS‐CoV‐2 and its diagnostics and treatment options in human body (Iyer et al., 2020).

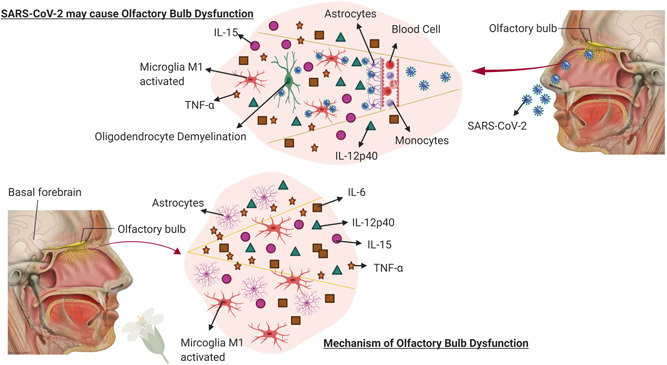

The blood–brain and blood–cerebrospinal fluid barrier play a decisive role in maintaining homeostasis as well as protecting the brain from free passages of pathogens like viruses (human coronavirus), where the entry often occurs via peripheral nerves especially the olfactory sensory neurons (Dahm et al., 2016; McGavern & Kang, 2011). Recently, it was observed that loss of smell (hyposmia) was manifested among the COVID‐19 patients who were admitted in the hospitals (Ling et al., 2020). We propose a hypothetical mechanism for the entry of SARS‐CoV‐2 inside the CNS via olfactory bulb, where viral lesions have the possibility to trigger the microglia 1 (M1) phenotype which in response could activate the proinflammatory cytokines. This may result in the secretion of cytokines which may induce demyelination in the nervous system. Our hypothetical mechanism was also supported by Das, Mukherjee, and Ghosh (2020) where the authors have observed that SARS‐CoV‐2 might exhibit an intrinsic capability to infect the neural cells and could spread from CNS to the periphery via transneuronal routes. Also Xydakis et al. (2020) and Gómez‐Iglesias et al. (2020) have stated that the virus has neuroinvasive potential and has the possibility to enter the brain through the olfactory bulb. Similar various recent studies related to COVID‐19 and neurological manifestations have been reported in Table 1. It has been reported that the SARS‐CoV‐2 enters the CNS via viral interaction with membrane‐bound ACE‐2 receptors which are expressed not only in nasal and oral mucosa but also in the nervous system (Dinkin et al., 2020; Li et al., 2020; Marinosci et al., 2020). In addition, the ACE2 receptors present in endothelial cells of the brain could be a possible reason for SARS‐CoV‐2 infection induced stroke as well as encephalitis (Nath, 2020). When the cells of the neuroepithelium are damaged by virus, they may recruit inflammatory cells to the site and trigger cytokine storm, causing subsequent damage to neurons and neurogenesis (Whitcroft et al., 2020). Armocida et al. (2020) have reported that COVID‐19 patients presenting with smell‐related symptoms should be provided with appropriate precautions as they might have an impact on neurological conditions as well as immunosuppression. De Santis (2020) has reported that SARS‐CoV‐2 could enter the CNS via olfactory bulb which might trigger cytokine storm, causing dysfunction in the brainstem and further leading to neuronal death. This mechanism of SARS‐CoV‐2 inside CNS raises questions on the possible common link between COVID‐19 and smell dysfunctions that might play a possible role in causing various neurodegenerative disorders. Reports have suggested that smell or olfactory dysfunction is a sensitive indicator for various neurodegenerative diseases such as Parkinson's diseases (PD), alzheimer's diseases (AD), and dementia (Ponsen et al., 2004; Richard, 2013; Velayudhan & Lovestone, 2009). The major player in smell dysfunction is the basal forebrain cholinergic system which regulates various neurotransmitters in the brain. The cholinergic neurons project into the olfactory bulb and modulate various neurological activities which stimulate immune response when a foreign agent invades the CNS. When there is a damage or defect in the cholinergic neurons, this might result into the activation of M1 phenotype and excite inflammatory mediators including IL‐6, IL‐12p40, IL‐15, and tumour necrosis factor‐α (TNF‐α) at a high level which has the possibility of neuroinflammation and cell death (Doursout et al., 2013; Richard, 2013; Wang, Zhou, Brand, & Huang, 2009). This detailed hypothetical mechanism has been depicted in Figure 1.

Table 1.

Studies related to COVID‐19 and neurological manifestations

| S. no | Type of study | Country where the study conducted | Concluding remarks | Manifestation | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Letter to the editor | Italy | The cause behind olfactory alterations in COVID‐29 could be due to infection in CNS rather than peripheral damage in nasal neuroepithelium. And gustatory alterations will be followed after olfactory disorder | Alterations in olfactory/gustatory functions | Ralli et al. (2020) |

| 2. | Letter to the editor | Switzerland | It is reported that anosmia could be used as an early prediction marker to detect this viral infection. Hence, scientific community has to focus on these symptoms and should make mandatory to test olfaction signs in COVID‐9 patients | Loss of smell or taste | Marinosci, Landis, and Calmy (2020) |

| 3. | Clinical update | London | The COVID‐19 patients are mainly associated with olfactory symptoms. This symptom should be used as a sign for self‐isolation and testing of COVID‐19. The authors suggest conducting psychophysical assessment will be more reliable in COVID‐19 patients | Loss of smell or taste | Whitcroft et al. (2020) |

| 4. | Research article | Belgium, Italy, Spain, France | The olfactory and gustatory are most common symptoms observed in Europeans affected with COVID‐19. The authors suggest that the international scientific community should recognise sudden olfactory or gustatory dysfunction as important sign of COVID‐19 | Olfactory and gustatory dysfunction | Lechien et al. (2020) |

| 5. | Correspondence | United States of America | It is evident that COVID‐19 does not manifest upper respiratory form of infections such as red, runny, stuffy or itchy nose. Hence, the authors comment that based on these observations, this virus could also be a neurotropic virus which is site‐specific for olfactory system | Anosmia with or without dysgeusia | Xydakis et al. (2020) |

| 6. | Correspondence | Italy | The authors have reported that COVID‐19 patient presenting with smell‐related symptoms should be provided with appropriate precautions as they might have an impact on neurological conditions as well as immunosuppression | Loss of smell or taste | Armocida et al. (2020) |

| 7. | Review article | India | The authors have stated that patients with altered mental health or with smell and taste dysfunction must be tested for COVID‐19. Also more autopsies of brain from COVID‐19 affected patients should be conducted to track down the neurological manifestation of this viral infection | Mild (anosmia and ageusia) to severe (encephalopathy) | Das et al. (2020) |

| 8. | Short report | United States of America | The authors reported two cases who were infected with COVID‐19. The first case showed symptoms for Hunt and Hess (H&H) grade 3 aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage (SAH). The second case was symptoms of Ischaemic stroke with massive haemorrhagic conversion. But virus was not present in CSF | Hunt and Hess (H&H) grade 3 aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage (SAH). Ischaemic stroke | Al Saiegh et al. (2020) |

| 9. | Case report | New York | The authors reported a case who had Parkinson's disease was positive for COVID‐19; it was observed that the post‐mortem reports of COVID‐19 patient revealed that the virus was present in the neural and capillary endothelial cells in frontal lobe tissue | Normal symptoms of COVID‐19 | Paniz‐Mondolfi et al. (2020) |

| 10. | Letter to the editor | China | The authors report a rare case of a patient diagnosed with COVID‐19 who manifested with concomitant neurological symptoms such as altered consciousness and psychiatric symptoms | Altered consciousness and psychiatric symptoms | Yin et al. (2020) |

| 11. | Review article | Iran | Through this review article the authors have suggested that COVID‐19 patients do have mild to severe neurological manifestation such as headache, anosmia, Febrile seizures, convulsions, change in mental status, and encephalitis | Febrile seizures, convulsions, change in mental status, and encephalitis | Asadi‐Pooya and Simani (2020) |

| 12. | Case report | United States of America | The authors have reported a case of 74 year old patients who had history of Parkinson's disease was positive for COVID‐19. Further examination revealed that the patient has encephalopathy, nonverbal and unable to follow any commands | Encephalitis | Filatov, Sharma, Hindi, and Espinosa (2020) |

| 13. | Special editorial | Bethesda | The author have stated that ACE2 is also found in the endothelial cells of brain which could increase the possibility of stroke due to SARS‐CoV‐2 infection and also encephalitis as a potential complication. | Stroke, encephalitis | Nath (2020) |

| 14. | Case report | United States of America | The authors report a case of 72‐year‐old man who had history of hypertension, coronary heart disease, diabetes and kidney issues. The patient was also positive for COVID‐19. The authors observed that the patients had symptoms of seizures, which could be possible due to virus invading the CNS | Seizures | Sohal and Mossammat (2020) |

| 15. | Letter to the editor | Italy | The author have reported that SARS‐CoV‐2 could enter the CNS via olfactory bulb and may reach brainstem causing dysfunction and neuronal death. The author also suggest that this might trigger immune response | ‐ | De Santis (2020) |

| 16. | Perspective | China | The authors have reported that COVID‐19 patients are mainly known to have respiratory symptoms but the initial symptoms they have are kind of neurological one's | Loss of smell, mild cognitive impairment, altered taste, nerve pain, ataxia, etc | Zhou et al. (2020) |

| 17. | Retrospective study | Chicago | Through this study, the authors have reported that neurological manifestations of COVID‐19 could be highly variable and may be a serious complication of this infection | Encephalopathy, cognitive impairment, seizures, dysgeusia, etc | Pinna et al. (2020) |

| 18. | Review article | Philadelphia | The author has suggested that as COVID‐19 disease triggers the cytokine storm; hence, it may also trigger various auto‐immune diseases such as acute paralytic disease like Guillain‐Barre Syndrome | Guillain‐Barré Syndrome | Dalakas (2020) |

| 19. | Review article | Pakistan | The authors have suggested that the COVID‐19 patients with neurological manifestations must be given utmost care and high priority index as it may also cause severe complications | Headache, dizziness, encephalopathy, and delirium | Ahmad and Rathore (2020) |

| 20. | Systematic review | United States of America | In this review article, the authors have also suggested that the SARS‐CoV‐2 infection mainly spreads through cribriform plate or olfactory bulb and could disseminate viz trans‐synaptic transfer | Hyposmia, headaches, encephalitis, demyelination, neuropathy, and stroke | Montalvan, Lee, Bueso, De Toledo, and Rivas (2020) |

Abbreviations: COVID‐19, coronavirus 2019; CNS, central nervous system; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; SARS‐CoV‐2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2.

Figure 1.

Mechanism of action for COVID‐19 neuroinvasion. Figure 1 depicts the hypothetical mechanism of entry of SARS‐CoV‐2 inside the CNS via olfactory bulb along with the mechanism involved in olfactory bulb dysfunction. This image is evident that both the pathways of mechanism are similar where the M1 phenotype of microglia gets activated which may further stimulate the pro‐inflammatory cytokines that have the possibility of resulting in neuroinflammation. COVID‐19, coronavirus 2019; CNS, central nervous system; M1, microglia 1; SARS‐CoV‐2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

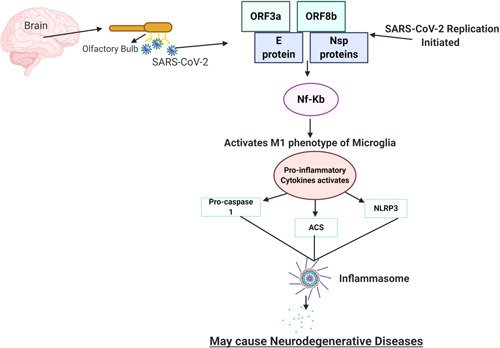

When this M1 phenotypes are activated, it might produce the proinflammatory cytokines or enhance phagocytosis or apoptosis which might contribute to the development of various neurodegenerative disorders (Seo, Kim, & Kang, 2018). After the entry of SARS‐CoV‐2 into the olfactory bulb, it possibly results in viral replication forming the ORF3a, ORF8b, E and other viral proteins. These proteins may also activate the (nuclear factor kappa‐light‐chain‐enhancer of activated B cells) NF‐Kb pathway followed by other proinflammatory cytokines such as TNF‐α, interleukin ‐1b (IL‐1b), and interleukin‐6 (IL‐6; Figure 2). This will bring to light the prominent proteins such as α‐synuclein and amyloid fibres which could get aggregated in neurodegenerative disorders. This inflammatory environment in the brain could also trigger oxidative stress mediators such as reactive oxygen species and nitrogen species, finally resulting in loss of dopamine (DA) neurons or the aggregation of amyloid fibrils forms, soluble proteins which assemble to form insoluble fibres that are resistant to degradation, which is the major pathogenesis of PD and AD (Hassanzadeh & Rahimmi, 2019; Kaavya et al., 2020; Rambaran & Serpell, 2008; Venugopal, Mahalaxmi, Venkatesh, & Balachandar, 2019).

Figure 2.

Depiction of the possible role of SARS‐CoV‐2 to cause neurodegenerative diseases. The entry of SARS‐CoV‐2 in the CNS through olfactory bulb upon nasal infection may possibly cause inflammation and demyelination. Upon binding with the olfactory bulb, the viral replication is initiated. ORF3a, ORF8b, E proteins, and the NF‐KB pathway activate the inflammasome pathway through various means, leading to the activation of cytokine. This results in a cytokine storm, which further results into various neuronal inflammations and may result into neurodegenerative disorders. CNS, central nervous system; SARS‐CoV‐2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

2. CONCLUSION

While most studies related to COVID‐19 are in its nascent stages, a more in‐depth research is required in this domain to enhance the knowledge about this virus on neuroinvasion. As described so far, COVID‐19 is an acute respiratory infection which demonstrates neurotropic capacities, thus allowing the virus to gain dormancy and might inhibit immunological reactions in the host cell. It has been hypothesised that SARS‐CoV‐2 enters the neuroepithelium by binding to the olfactory receptors. Further, the virus subsequently enters the brain stem and the medulla oblongata, causing respiratory problems (De Santis, 2020; Ralli, Di Stadio, Greco, de Vincentiis, & Polimeni, 2020). Based on the experimental studies in mice, SARS‐CoV and MERS‐CoV had revealed that the virus could enter the brain possibly via the olfactory bulb, following its spread to some specific brain parts such as thalamus and brainstem (Li et al., 2020). In a recent study, it was observed that the postmortem reports of COVID‐19 revealed that the virus was present in the neural and capillary endothelial cells in frontal lobe tissue (Paniz‐Mondolfi et al., 2020). Interestingly, the olfactory dysfunctions were also found in patients without other symptoms, indicating that these abnormalities can be beneficial in early identification of disease (Lechien et al., 2020). Considering the high similarity between SARS‐CoV and SARS‐CoV‐2, the patients affected with COVID‐19 or recovered patients have probable chances to infect various organs including lungs, heart, kidney, brain and gastrointestinal tracts (Baig, Khaleeq, Ali, & Syeda, 2020). Hence, this review suggests that through olfactory bulb the SARS‐CoV‐2 might infect the brain which was also evaluated by Matthew (2020) and Ling et al. (2020) for which further investigation are required. The possible link between COVID‐19 and neurological conditions could help us to understand the neuroinvasion properties of the virus and develop precautionary measures to prevent it. In conclusion, this review warrants more research in this area to uncover the mechanism of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection via olfactory bulb and its implications in neurodegenerative diseases.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors declare that there are no conflict of interests.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The author (Vellingiri Balachandar) would like to thank Bharathiar University for providing the necessary infrastructure facility and the Science and Engineering Research Board (SERB; ECR/2016/001688), Government of India, New Delhi for providing necessary help in carrying out this review process.

Mahalaxmi I, Kaavya J, Mohana Devi S, Balachandar V. COVID‐19 and olfactory dysfunction: A possible associative approach towards neurodegenerative diseases. J Cell Physiol. 2021;236:763–770. 10.1002/jcp.29937

REFERENCES

- Ahmad, I. , & Rathore, F. A. (2020). Neurological manifestations and complications of COVID‐19: A literature review. Journal of Clinical Neuroscience, 77, 8–12. 10.1016/j.jocn.2020.05.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al Saiegh, F. , Ghosh, R. , Leibold, A. , Avery, M. B. , Schmidt, R. F. , Theofanis, T. , … Gooch, M. R. (2020). Status of SARS‐CoV‐2 in cerebrospinal fluid of patients with COVID‐19 and stroke. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry, 10.1136/jnnp-2020-323522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armocida, D. , Pesce, A. , Raponi, I. , Pugliese, F. , Valentini, V. , Santoro, A. , & Berra, L. V. (2020). Anosmia in COVID‐19: severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 through the nasoliary epithelium and a possible spreading way to the central nervous system—A purpose to study. Neurosurgery, 10.1093/neuros/nyaa204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asadi‐Pooya, A. A. , & Simani, L. (2020). Central nervous system manifestations of COVID‐19: A systematic review. Journal of the Neurological Sciences, 413, 116832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baig, A. M. , Khaleeq, A. , Ali, U. , & Syeda, H. (2020). Evidence of the COVID‐19 virus targeting the CNS: Tissue distribution, host‐virus interaction, and proposed neurotropic mechanisms. ACS Chemical Neuroscience, 11(7), 995–998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balachandar, V. , Mahalaxmi, I. , Mohana Devi, S. , Kaavya, J. , Senthil Kumar, N. , Gracy, L. , … Ssang‐Goo, C. (2020). Follow‐up studies in COVID‐19 recovered patients ‐ Is it mandatory. Science of the Total Environment, 729, 139021. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.139021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahm, T. , Rudolph, H. , Schwerk, C. , Schroten, H. , & Tenenbaum, T. (2016). Neuroinvasion and inflammation in viral central nervous system infections. Mediators of Inflammation, 2016, 8562805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalakas, M. C. (2020). Guillain‐Barré syndrome: The first documented COVID‐19‐triggered autoimmune neurologic disease: More to come with myositis in the offing. Neurology(R) Neuroimmunology & Neuroinflammation, 7(5), e781. 10.1212/NXI.0000000000000781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das, G. , Mukherjee, N. , & Ghosh, S. (2020). Neurological insights of COVID‐19 pandemic. ACS Chemical Neuroscience, 11, 1206–1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Santis, G. (2020). SARS‐CoV‐2: A new virus but a familiar inflammation brain pattern. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, S0889‐1591(20), 30676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding, Y. Q. , He, L. , Zhang, Q. L. , Huang, Z. , Che, X. , Hou, J. , … Jiang, S. (2004). Organ distribution of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) associated coronavirus (SARS‐CoV)in SARS patients: Implications for pathogenesis and virus transmission pathways. Journal of Pathology, 203, 622–630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinkin, M. , Gao, V. , Kahan, J. , Bobker, S. , Simonetto, M. , Wechsler, P. , … Leifer, D. (2020). COVID‐19 presenting with ophthalmoparesis from cranial nerve palsy. Neurology, 10.1212/WNL.000000000000970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doursout, M. F. , Schurdell, M. S. , Young, L. M. , Osuagwu, U. , Hook, D. M. , Poindexter, B. J. , … Bick, R. J. (2013). Inflammatory cells and cytokines in the olfactory bulb of a rat model of neuroinflammation; insights into neurodegeneration? Journal of Interferon & Cytokine Research: The Official Journal of the International Society for Interferon and Cytokine Research, 33(7), 376–383. 10.1089/jir.2012.0088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filatov, A. , Sharma, P. , Hindi, F. , & Espinosa, P. S. (2020). Neurological complications of coronavirus disease (COVID‐19): Encephalopathy. Cureus, 12(3), e7352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez‐Iglesias, P. , Porta‐Etessam, J. , Montalvo, T. , Valls‐Carbó, A. , Gajate, V. , Matías‐Guiu, J. A. , … Matías‐Guiu, J. (2020). An online observational study of patients with olfactory and gustory alterations secondary to SARS‐CoV‐2 infection Frontiers in Public Health, 8, 243. 10.3389/fpubh.2020.00243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassanzadeh, K. , & Rahimmi, A. (2019). Oxidative stress and neuroinflammation in the story of Parkinson's disease: Could targeting these pathways write a good ending? Journal of Cellular Physiology, 234, 23–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iyer, M. , Jayaramayya, K. , Subramaniam, M. D. , Lee, S. B. , Dayem, A. A. , Cho, S. G. , & Vellingiri, B. (2020). COVID‐19: An update on diagnostic and therapeutic approaches. BMB Reports, 53(4), 191–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaavya, J. , Mahalaxmi, I. , Dhivya, V. , Venkatesh, B. , Arul, N. , Mohana Devi, S. , … Balachandar, V. (2020). Unraveling correlative roles of dopamine transporter (DAT) and Parkin in Parkinson's disease (PD)‐A road to discovery? Brain Research Bulletin, 157, 169–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koralnik, I. J. , & Tyler, K. L. (2020). COVID‐19: A global threat to the nervous system. Annals of Neurology, 88(1), 1–11. 10.1002/ana.25807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lechien, J. R. , Chiesa‐Estomba, C. M. , De Siati, D. R. , Horoi, M. , Le Bon, S. D. , Rodriguez, A. , … Saussez, S. (2020). Olfactory and gustatory dysfunctions as a clinical presentation of mild‐to‐moderate forms of the coronavirus disease (COVID‐19): A multicenter European study. European Archives of Oto‐Rhino‐Laryngology, 1–11. 10.1007/s00405-020-05965-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y. C. , Bai, W. Z. , & Hashikawa, T. (2020). The neuroinvasive potential of SARS‐CoV2 may play a role in the respiratory failure of COVID‐19 patients. Journal of Medical Virology, 92, 1–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling, M. , Mengdie, W. , Shanghai, C. , Quanwei, H. , Jiang, C. , Candong, H. , … Bo, Hu (2020). Neurological manifestations of hospitalized patients with COVID‐19 in Wuhan, China: A retrospective case series study. medRxiv. 10.1101/2020.02.22.20026500 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marinosci, A. , Landis, B. N. , & Calmy, A. (2020). Possible link between anosmia and COVID‐19: Sniffing out the truth. European Archives of Oto‐Rhino‐Laryngology, 1–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthew, A. (2020, March 24). Lost smell and taste hint COVID‐19 can target the Nervous system. The Scientist.

- McGavern, D. B. , & Kang, S. S. (2011). Illuminating viral infections in the nervous system. Nature Reviews Immunology, 11, 318–329. 10.1038/nri2971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montalvan, V. , Lee, J. , Bueso, T. , De Toledo, J. , & Rivas, K. (2020). Neurological manifestations of COVID‐19 and other coronavirus infections: A systematic review. Clinical Neurology and Neurosurgery, 194, 105921. 10.1016/j.clineuro.2020.105921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nath, A. (2020). Neurologic complications of coronavirus infections. Neurology, 94(19), 809–810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paniz‐Mondolfi, A. , Bryce, C. , Grimes, Z. , Gordon, R. E. , Reidy, J. , Lednicky, J. , … Fowkes, M. (2020). Central nervous system involvement by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus ‐2 (SARS‐CoV‐2). Journal of Medical Virology, 92, 699–702. 10.1002/jmv.25915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinna, P. , Grewal, P. , Hall, J. P. , Tavarez, T. , Dafer, R. M. , Garg, R. , … Silva, I. D. (2020). Neurological manifestations and COVID‐19: Experiences from a tertiary care center at the frontline. Journal of the Neurological Sciences, 415, 116969. 10.1016/j.jns.2020.116969 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponsen, M. M. , Stoffers, D. , Booij, J. , van Eck‐Smit, B. L. F. , Wolters, E. C. , & Berendse, H. W. (2004). Idiopathic hyposmia as a preclinical sign of Parkinson's disease. Annals of Neurology, 56(2), 173–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ralli, M. , Di Stadio, A. , Greco, A. , de Vincentiis, M. , & Polimeni, A. (2020). Defining the burden of olfactory dysfunction in COVID‐19 patients. European Review for Medical and Pharmacological Sciences, 24(7), 3440–3441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rambaran, R. N. , & Serpell, L. C. (2008). Amyloid fibrils: Abnormal protein assembly. Prion, 2(3), 112–117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richard, L. D. (2013, September 30). Smell and the degenerating brain. The Scientist.

- Seo, Y. , Kim, H. S. , & Kang, K. S. (2018). Microglial involvement in the development of olfactory dysfunction. Journal of Veterinary Science, 19(3), 319–330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohal, S. , & Mossammat, M. (2020). COVID‐19 presenting with seizures. IDCases, 20, e00782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velayudhan, L. , & Lovestone, S. (2009). Smell identification test as a treatment response marker in patients with Alzheimer disease receiving donepezil. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology, 29, 387–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vellingiri, B. , Jayaramayya, K. , Iyer, M. , Narayanasamy, A. , Govindasamy, V. , Giridharan, B. , … Subramaniam, M. D. (2020). COVID‐19: A promising cure for the global panic. Science of the Total Environment, 725, 138277. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venugopal, A. , Mahalaxmi, I. , Venkatesh, B. , & Balachandar, V. (2019). Mitochondrial calcium uniporter as a potential therapeutic strategy for alzheimer's disease (AD). Acta Neuropsychiatrica, 32(2), 65–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H. , Zhou, M. , Brand, J. , & Huang, L. (2009). Inflammation and taste disorders: mechanisms in taste buds. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1170, 596–603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitcroft, K. L. , & Hummel, T. (2020). Olfactory dysfunction in COVID‐19: Diagnosis and management. Journal of the American Medical Association, 10.1001/jama.2020.8391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xydakis, M. S. , Dehgani‐Mobaraki, P. , Holbrook, E. H. , Geisthoff, U. W. , Bauer, C. , Hautefort, C. , … Hopkins, C. (2020). Smell and taste dysfunction in patients with COVID‐19. The Lancet Infectious Diseases, S1473‐S3099(20), 30293. 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30293-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R. , Feng, W. , Wang, T. , Chen, G. , Wu, T. , Chen, D. , … Xiang, D. (2020). Concomitant neurological symptoms observed in a patient diagnosed with coronavirus disease 2019. Journal of Medical Virology, 10.1002/jmv.25888 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y. , Li, W. , Wang, D. , Mao, L. , Jin, H. , Li, Y. , … Hu, B. (2020). Clinical time course of COVID‐19, its neurological manifestation and some thoughts on its management. Stroke and Vascular Neurology, 5(2), 177–179. 10.1136/svn-2020-000398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]