Abstract

Mortality threats are among the strongest psychological threats that an individual can encounter. Previous research shows that mortality threats lead people to engage in unhealthy compensatory consumption (i.e., overeating), as a maladaptive coping response to threat. In this paper, we propose that reminders of heroes when experiencing mortality threat increases perceptions of personal power, which in turn buffers the need to engage in unhealthy compensatory consumption. We test and find support for our predictions in a series of four studies that include real‐world Twitter data after a series of terrorist attacks in 2016–2017, and three experimental studies conducted online and in the field with behavioral measures after Day of the Dead and during COVID‐19 pandemic. These findings advance the literature on compensatory consumption, mortality threats, and the psychological functions of heroes.

Keywords: compensatory consumption, coronavirus, heroes, mortality salience, power

1. INTRODUCTION

Unhealthy consumption is a global problem that public policy makers and organizations such as UNICEF and World Health Organization aim to understand the reasons and reduce the consequences of unhealthy consumption across the world. Although there may be several reasons for why consumers engage in unhealthy consumption, previous research shows that one of the reasons for why consumers engage in unhealthy consumption is to mitigate the effects of psychological threats they experience, in which unhealthy consumption acts as having a compensatory role (Ferraro, Shiv, & Bettman, 2005; Hirschberger, & Ein‐Dor, 2005). In this study, we examine a way that consumers may engage in less unhealthy compensatory consumption when they experience a mortality threat, which is one of the most experienced psychological threat consumers experience during their lifetime. We first provide the research motivation.

Individuals strive to organize their perceptions of the world and create meaning by developing expected relationships (e.g., good things happen to good people) and then perceiving events through the prism of these mental representations (Heine, Proulx, & Vohs, 2006). Meaning can be disrupted by incoming information and by experiences that violate one's beliefs and values (Proulx & Inzlicht, 2012). Certain situations can challenge one's sense of meaning in life, resulting in an experience of a psychological threat (Baumeister & Vohs, 2002). Research in psychology and marketing shows that psychological threats such as stereotype threats (Gill & Lei, 2018; Steele & Aronson, 1995), threats to self‐image (Gill & Lei, 2018; Thomas, Saenger, & Bock, 2017), threats to ego (Larson & Denton, 2014), and reminders of death (Heine et al., 2006) threaten one's sense of meaning in life.

According to the meaning maintenance model (Heine et al., 2006), when people experience psychological threats, they attempt to reestablish meaning by making mental adjustments. Individuals try to reestablish their threatened meaning by relying on alternative meaning representations (Heine et al., 2006). Some strategies to reestablish meaning and cope with psychological threats include reinforcing social connections (Wildschut, Sedikides, Arndt, & Routledge, 2006), perceiving time as a continuous interconnection between the past with the present and the future (Sarial‐Abi, Vohs, Hamilton & Ulqinaku, 2017), and believing in supernatural agents such as angels, devils, jinns, ancestor spirits, and God (Jong, Halberstadt, & Bluemke, 2012; Kay, Gaucher, Napier, Callan, & Laurin, 2008;). In terms of behavior in the marketplace, consumers engage in compensatory consumption, mostly unhealthy compensatory consumption, to cope with psychological threats (Mandel, Rucker, Levav, & Galinsky, 2017). While these activities differ greatly, they are similar in the sense that they offer individuals a chance to reaffirm representations of certain aspects of their lives and therefore, offer routes to coping with psychological threats.

In this study, we focus on instances when meaning is disrupted by one particular psychological threat, namely, mortality threat. We suggest that reminders of heroes reduce unhealthy compensatory consumption (i.e., overeating) when consumers experience mortality threats. The rationale is that heroes, known for their personal power, increase the perceptions of personal power in others (i.e., the power to act autonomously and to control one's own resources; Van Dijke & Poppe, 2006).

These research findings extend the literature on psychological threats and, more specifically, mortality threats by studying how consumers can engage in less unhealthy compensatory consumption when they experience a mortality threat. Although previous research suggests ways to cope with mortality threats, this study is limited to providing evidence for how to reduce unhealthy compensatory consumption when consumers experience mortality threats. Second, we identify perceptions of personal power as an active ingredient in this process, a novel finding that is relevant to the understanding and development of theories relating to coping with psychological threats. Previous research shows that building social connections (Wildschut et al., 2006) and connecting the present, past and future (Sarial‐Abi et al., 2017) are possible ways to cope with psychological threats. Here, we suggest that perceived personal power is another avenue to coping with psychological threat, namely, the mortality threat. Third, the finding that thinking about heroes can increase perceptions of personal power and that this is evident when consumers experience psychological threats makes a further novel contribution to the literature. This study supports previous research showing that heroes influence others psychologically, particularly during times of threat (e.g., Allison & Goethals, 2011; Kinsella, Ritchie, & Igou, 2015b; Sullivan & Venter, 2005); however, this finding also adds to existing scholarship on heroes and psychological threat (Green, Van Tongeren, Cairo, & Hagiwara, 2017; McCabe, Carpenter, & Arndt, 2016) by specifying a specific mediating variable: personal power.

1.1. Mortality threats as psychological threats

Psychological threats are uncomfortable and unpleasant psychological states that arise from a discrepancy between the current state and a desired end state (Folkman & Lazarus, 1984; Han, Duhachek, & Rucker, 2015; Kim & Rucker, 2012). Mortality threats are among the strongest psychological threats that any individual can encounter, disrupting the meaning of life (Arndt, Solomon, Kasser, & Sheldon, 2004; Becker, 1973; Routledge et al., 2011). Mortality threats are activated by fear of one's own death, by fear of losing someone dear, and even by watching a movie or reading news or a story that reminds individuals of their mortality and how death is an imminent reality (Rosenblatt, Greenberg, Solomon, Pyszczynski, & Lyon, 1989).

From a psychological perspective, mortality threats are important because they can decrease life satisfaction and job performance (De Clercq, Haq, & Azeem, 2017), decrease psychological well‐being, decrease prosocial intentions (Jonas, Schimel, Greenberg, & Pyszczynski, 2002) and increase stigmatization (Yousaf & Xiucheng, 2018). Psychological threats related to death have important consequences for consumer behavior as well. These threats can (a) affect individuals' preference towards luxury goods (e.g., Rolex watches) versus nonluxury goods (e.g., Pringles chips; Mandel & Heine, 1999), (b) affect preference for materialism and conspicuous consumption (Arndt et al., 2004) when consumers have the perception of being observed (vs. not) by others (Choi, Kwon, & Lee, 2007), (c) make individuals indulge more in impulsive consumption (Choi et al., 2007; Ruvio, Somer, & Rindfleisch, 2014), (d) make individuals prefer brands that are in line with their cultural belongingness (i.e., domestic brands vs. foreign ones; Liu & Smeesters, 2010), (e) lead to higher preferences towards vintage products (Sarial‐Abi et al., 2017), (f) result in resistance to product innovation (Boeuf, 2019), and (g) lead to greater propensity to use products and services designed to maintain a youthful image (Moschis, 1994). Taken together, these findings reiterate that mortality threats impact an individual's psychological state and everyday consumer behavior in a number of important ways. Important to the present investigation is the idea that mortality threats lead people to engage in compensatory consumption as a (maladaptive) form of coping. We propose that reminders of heroes reduce unhealthy compensatory consumption by consumers who experience mortality threats.

1.2. The psychological influence of heroes: Focus on personal power

The concept of heroes has existed since ancient times and remains important in modern society. In a survey conducted in 25 countries, 66% of people reported having at least one hero in their lives (Kinsella, Ritchie, & Igou, 2015a). While heroes are common in people's everyday lives, they are not easy to conceptualize theoretically (Franco, Blau, & Zimbardo, 2011; Kinsella et al., 2015a). A hero is depicted as a caring character who fights to make a positive difference in someone's life, winning the respect and admiration of the masses (Holt & Thompson, 2004). Recent prototype research identified being brave, fearless, selfless, self‐sacrificing, honest, and strong and having moral integrity as the central features of heroes (Kinsella et al., 2015a). Heroism is associated with “having guts” (i.e., showing gumption) and undertaking actions to help others, even though doing so may cause the helper's death or injury (Becker & Eagly, 2004).

Heroes are important for redefining individuals' well‐being in contemporary culture (Franco, Efthimiou, & Zimbardo, 2016). Reminders of heroes help individuals with self‐identification (Veen & College, 1994) and affect self‐perceptions (Sullivan & Venter, 2005). Heroes have psychological importance to humankind (Sullivan & Venter, 2005). Based on the lay theories that people have on the psychological role of heroes, there are three main psychological functions served by heroes: enhancing (e.g., providing motivation, hope, inspiration, and morale), moral modeling (e.g., reminding people about the concept of good, values, and making the world better), and protecting (e.g., from danger, threats, and evil) (Kinsella et al., 2015b). Importantly, heroes provide psychological resources to individuals, particularly during times of threat (e.g., Coughlan, Igou, van Tilburg, Kinsella, & Ritchie, 2019; Kinsella et al., 2015b; Sullivan & Venter, 2005).

Based on the literature reviewed so far, it is reasonable to argue that thinking about heroes reduces mortality threats. A key contribution of the current research is to test this assertion and, moreover, to attempt to identify an additional variable that may account for the relationship between heroes and mortality threats: personal power.

Perceptions of power are defined as the ability of an individual to achieve what the individual desires without being influenced by others (Galinsky, Magee, Gruenfeld, Whitson, & Liljenquist, 2008; Galinsky, Rucker, & Magee, 2015; Van Dijke & Poppe, 2006). It is a need to act for yourself, to control the environment, to overcome resistance, to reach goals and to pursue autonomy (Van Dijke & Poppe, 2006). There are two types of power: personal power and social power. Social power is defined as the ability to make others behave in a way they would not otherwise behave. Personal power is related to autonomy over one's own actions and resources (Lammers, Stoker, & Stapel, 2009).

Previous research shows that enhanced perceptions of personal power can make individuals feel less threatened (Anderson & Berdahl, 2002; Kay et al., 2008). This is because individuals with higher perceptions of personal power demonstrate a lower tendency to feel threatened (Anderson & Berdahl, 2002); they are less concerned about what happens in their social environments because they perceive themselves to be independent and free from others (Lammers et al., 2009).

Heroes are often described as being powerful (Kinsella et al., 2015a). While heroes are vested with power (Becker, 1973; Kinsella et al., 2015a; Lash, 1995), they display “autonomy, not authority” (Lash, 1995, p. 6). Heroes are powerful, and their power comes within them; it is not appointed to them by others (Lash, 1995). Heroes have a high degree of autonomy, which is the main feature of personal power, and they employ their power for independence over their actions rather than to push others to do something (Lash, 1995). Consequently, heroes are likely to be pillars that others turn to when facing a psychological threat. Heroes can provide psychological protection to individuals (e.g., protection from evil), they can instill hope, and they provide guidance to people (Kinsella et al., 2015b) when individuals experience psychological threats. Supporting this view, previous research has shown that reminders of heroes in product packaging bring to mind safety and protection related to the product on which the hero label is placed (Masters & Mishra, 2019)—in essence, the individual feels a strong connection to the vicarious heroic attributes, which in turn influences subsequent behavior (Holt & Thompson, 2004).

2. THE PRESENT RESEARCH

Drawing from these ideas and empirical findings, we propose that when consumers experience mortality threats, reminders of heroes (vs. not) influence their perceptions of power. Consequently, mortality threats affect their behavior less, reducing their tendency to engage in unhealthy compensatory consumption as a coping mechanism against mortality threats. Hence, we propose H1 and H2.

H1. When consumers experience mortality threats, reminders of heroes (vs. not) reduce unhealthy compensatory consumption.

H2. Perceptions of personal power mediate the effect of hero reminders on unhealthy compensatory consumption when consumers experience mortality threats.

We test our predictions H1 and H2 in a series of four studies. In Study 1, using real‐world Twitter data, we examine evidence for the relationship between reminders of heroes and mortality threats. We further examine evidence for the role of perceived sense of power in the relationship between reminders of heroes and mortality threats. In Studies 2a and 2b, we assess the evidence for the effect of mortality threats and reminders of heroes on unhealthy compensatory consumption with intentional and behavioral measures using online and field experiments. Finally, in Study 3, we examine evidence for the role of perceptions of personal power in the relationship between reminders of heroes and mortality threats on unhealthy compensatory consumption, using an intentional measure during a real‐world mortality threat context, namely, the global COVID‐19 pandemic. Additional information on the stimuli used in manipulations and the scales used to conduct the experiments is provided in the Supporting Information Material.1

3. STUDY 1

In this study, we tested the relationship between reminders of heroes and the experience of mortality threats. Moreover, we test the role of perceptions of power in the relationship between reminders of heroes and experience of mortality threats.

To test our predictions in a real‐life context, we used social users' tweets after a series of terrorist attacks that occurred in Turkey, Israel, and Germany between November 2016 and January 2017. We used terrorist attacks as a setting to test the relationship between the reminders of heroes and mortality threats because previous research suggests news on terrorist attacks results in enhanced mortality salience (Landau et al., 2004).

3.1. Materials and procedure

We collected Twitter posts immediately after news regarding specific terrorist attacks was aired on major TV channels. We collected data after the terrorist attacks that occurred between November 24th, 2016, and January 10th, 2017, for a total of 154,390 tweets. These terrorist attacks occurred in Turkey (i.e., Adana—November 24th, 2016; Istanbul Atatürk Airport—December 10th, 2016; Kayseri—December 17th, 2016; Ankara—December 19th, 2016; Reina—December 31st, 2016; and Izmir—January 5th, 2017), Germany (i.e., Berlin—December 20th, 2016), and Israel (i.e., Jerusalem—January 8th, 2017). We collected posts published by users of Twitter immediately after news of the terrorist attacks was released on major media channels (e.g., BBC and CNN). The maximum amount of time that passed between the start of the data collection and the announcement of the terrorist attack was 3 hr.

All the Twitter data were collected through the Twitter application programming interface (API) using the hashtag associated with the place of the attack. We collected data related to text and hashtags, author identification name and number, number of likes, number of retweets, number of previous posts of the author, and the number of friends and followers of the author. The API allows tweets related to a keyword (or a series of words) to be downloaded in real‐time (e.g., Rossi & Rubera, 2018). Given that the data were freely available online, no permission was required for further use (Tripathy, 2013). However, to ensure full compliance with the ethics of analyzing publicly available data, we did not include in any of our datasets the real name of the authors of the posts. The author's Twitter username was used only for the purpose of controlling whether multiple tweets were posted by the same user. After cleaning spam tweets from the data, we had a total of 154,390 tweets (original N = 170,093).

We used the Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count (LIWC2015) software to obtain proxies for reminders of heroes, the experience of mortality threat, and perceptions of personal power. LIWC2015 is composed of a dictionary, which includes approximately 6,400 words commonly used in everyday language and adapted to verbal speech common in social networks (also known as “netspeak”; Pennebaker, Boyd, Jordan, & Blackburn, 2015). LIWC2015 provides a score of the relative frequency of words in a tweet categorized in a series of clusters (e.g., heroes, death, power).

We composed the experience of the mortality threat measure by using the relative frequency of words in each tweet classified as related to death (e.g., bury, coffin, kill, dead, and death; Pennebaker et al., 2015; M = 1.631, SD = 2.729). To compose the reminders of the hero variable, we created a dummy variable that measured whether the word hero (or derivatives of it, such as heroic, heroism, or heroes) was mentioned in the tweet content or in the hashtags of each tweet posted during the identified time period. This variable took the value of 0 if the word hero was not contained in the text or hashtags and 1 if it was included (M = 0.05, SD = 0.21). To compose the perceptions of the personal power variable, we used the relative frequency of words in each tweet classified as related to power (e.g., strong, mighty, in command).

3.2. Results and discussion

The results revealed a negative relationship between reminders of heroes and experience of mortality threats (β = −.68, p < .001), controlling for the author of the post, number of likes and retweets, number of friends, followers, emotional valence, and previous posts shared by that author.2 These results provided initial evidence that people who are reminded of heroes experience weaker mortality threats. Robustness checks are provided in the Supporting Information Material section.

To test for the role of perceptions of personal power on the relationship between reminders of heroes and experience of mortality threat, we conducted a bootstrap mediation model analysis with STATA 15 with 1,000 replications and bias‐corrected confidence intervals. We used the reminders of the hero binary variable (explained above) as our main independent variable, the experience of mortality threat scores (explained above) as our main dependent variable, and perceptions of personal power (explained above) as the mediator. We used the same control variables as those above in the regression model. The results suggested a significant indirect effect of mediation (95% bias‐corrected confidence interval [CI]: −1,888,450 to −918,818.1) on the relationship between reminders of heroes and experience of mortality threat and a significant total effect (95% bias‐corrected CI: −1,888,451 to −918,818.8). Specifically, there was a positive relationship between reminders of heroes and perceptions of personal power (β = .81, p < .001) and a negative relationship between perceptions of personal power and experiences of mortality (β = −.11, p < .001).

Overall, these results suggest initial evidence of the relationship between reminders of heroes and the experience of mortality threats. Moreover, they provide initial evidence for the role of perceptions of personal power on the relationship between reminders of heroes and experiences of mortality threats. While we acknowledge the limitations of the correlational (and not causal) evidence of the relationships among our predicted variables, these results provide preliminary evidence for the predicted relationships using a natural context (i.e., Twitter) after the experience of terrorist attacks. In Studies 2a and 2b, we test our predictions in experimental settings.

4. STUDY 2a

In Study 2a, we test for the prediction that when consumers experience mortality threats as a response to a threat, they engage in unhealthy compensatory consumption, but reminders of heroes reduce the unhealthy compensatory consumption that is the behavioral indicator of the threat response (H1).

We randomly assigned participants to mortality threat (vs. control) and reminders of heroes (vs. not) conditions. We measured the intentions to engage in unhealthy compensatory consumption.

4.1. Participants

Two hundred participants (71 male; M = 36.62, SD = 12.78) participated in the experiment on the MTurk online platform in exchange for monetary compensation. This study used a two (mortality threat, control) by two (hero, no‐hero) between‐subjects design.

4.2. Materials and procedure

All the participants read that they would participate in a study on product preferences. We then randomly assigned participants to the mortality threat or control condition. Participants in the mortality threat condition were asked to take a few moments to think about their own death (Burke, Martens, & Faucher, 2010). Participants in the control condition were asked to take a few moments to think about a recent incident. Then, participants wrote a short paragraph about how they feel when thinking about their own death (past experience) and what would happen to them as they physically died (how they felt about the incident).

As a manipulation check, participants expressed the extent to which they felt their life was threatened and the extent to which they thought about death in that particular moment on two 7‐point scales (1 = Strongly Disagree and 7 = Strongly Agree). We tried collapsing the two items into a single variable—mortality threat manipulation check—with higher ratings indicating higher mortality threat (α = .57). Given the low value of Cronbach's α, we analyzed the two items separately rather than collapsing them into one unique variable.

We then randomly assigned the participants to the hero reminders or the no‐hero reminders condition. Consistent with previous research (Kinsella et al., 2015a), participants in the hero reminder condition were asked to “think of a person they considered a hero.” Participants in the no‐hero reminders condition were asked to “think of an acquaintance (i.e., someone you know slightly but, that is not a friend).” In both conditions, participants were asked to write down the name or the initials of the person they were thinking and briefly describe him/her.

As a manipulation check for the hero reminders condition, we asked participants to indicate the extent to which the person they described was considered heroic and the extent to which this person shows heroic behaviors on two 7‐point scales (1 = Strongly Disagree and 7 = Strongly Agree). Participants' responses were strongly related to each other (α = .97). Given the very high Cronbach's α score, we treated the items separately.

We then measured the participants' intentions to engage in unhealthy compensatory consumption. We asked participants to imagine that they have a bowl with one thousand M&Ms and a bowl with one thousand grapes in front of them. We asked them to imagine these two bowls in a randomized order. After each question, they indicated how much they would like to consume M&Ms or the grapes at that specific moment in time. We composed the unhealthy compensatory consumption score by calculating the difference between intentions to consume M&Ms and intentions to consume grapes (Min = −500, Max = 969, M CONSUMPTION = 5.21, SD = 204.48).

Participants also indicated the extent to which they like M&Ms and grapes on two 7‐point scales (1 = Far too little and 7 = Far too much). Moreover, participants indicated the extent to which they found M&Ms and grapes to be healthy and unhealthy on two 7‐point scales (1 = Far too little and 7 = Far too much). At the end, participants provided their demographic information and were thanked.

4.3. Results and discussion

4.3.1. Manipulation check and controls

As intended, participants in the mortality threat condition indicated that they felt their life was threatened more than the participants in the control condition, M THREAT = 3.54, SD THREAT = 1.56 versus M CONTROL = 1.61, SD CONTROL = 0.99, t(199) = 10.42, p < .001, Cohen's d = 1.48, and r = .59. Participants in the mortality threat condition indicated that they thought more about death than participants in the control condition, M THREAT = 3.54, SD THREAT = 1.56 versus M CONTROL = 1.61, SD CONTROL = 0.99, t(199) = 10.42, p < .001, Cohen's d = 1.48, and r = .59. Moreover, participants in the hero reminder condition indicated that they perceived the person they wrote about as more heroic than participants in the no‐hero reminder condition, M HERO = 6.26, SD HERO = 0.96 versus M NO‐HERO = 2.48, SD NO‐HERO = 1.52, t(199) = 20.92, p < .001, Cohen's d = 2.97, and r = .83, and they perceived the person's actions as more heroic in the hero reminder condition than in the no‐hero condition M HERO = 6.05, SD HERO = 1.18 versus M NO‐HERO = 2.57, SD NO‐HERO = 1.70, t(199) = 17.77, p < .001, Cohen's d = 2.38, the r = .77.

Moreover, the ratings for liking M&Ms (F(1, 196) = 0.10, p = .96) and grapes (F(1, 196) = 0.65, p = .581) were not significantly different in any of the conditions. Similarly, the perception of the healthiness of grapes (F(1, 196) = 0.29, p = .83) or the unhealthiness of M&Ms (F(1, 196) = 1.30, p = .274) did not differ among the four conditions. These findings rule out the possibility that the results are explained by higher liking of grapes or M&Ms or by healthy/unhealthy perceptions of grapes and M&Ms across the four conditions.

4.3.2. Unhealthy compensatory consumption

Consistent with H1, analysis of variance (ANOVA) analyses on intentions to engage in unhealthy compensatory consumption revealed a marginal interaction effect between mortality threat (vs. control) and hero (vs. no‐hero) reminder conditions, F(1, 196) = 3.002, p = .08. There was a main effect of mortality threat condition (F(1, 196) = 4.58, p = .034) and a main effect of hero reminder (F(1, 196) = 4.40, p = .037). Supporting H1, participants who were reminded of a hero (vs. not) had lower intentions to engage in unhealthy compensatory consumption when they were under the mortality threat condition, M HERO = −22.38, SD HERO = 156.22 versus M NO‐HERO = 86.32, SD NO‐HERO = 280.74, F(1, 196) = 7.47, p = .007, Cohen's d = 0.48, and r = .23. Participants' intentions to engage in unhealthy compensatory consumption did not differ among those who were reminded of a hero (vs. no‐hero) when they were under the control condition, M HERO = ‐33.96, SD HERO = 155.71 versus M NO‐HERO = ‐23.59, SD NO‐HERO = 153.99, F(1, 196) = 0.07, p = .798, Cohen's d = 0.07, and r = .04.

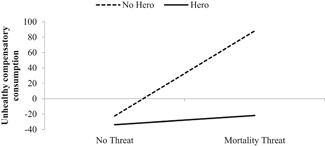

Moreover, consistent with previous research, participants who were not reminded of heroes engaged in more unhealthy compensatory consumption when they were under the mortality threat (vs. control) condition, F(1, 196) = 7.55, p = .007, Cohen's d = 0.49, and r = .24. As predicted, reminders of heroes mitigated participants' engagement in unhealthy compensatory consumption, so there was no difference in engagement in unhealthy compensatory consumption among participants who were under the mortality threat (vs. control) condition when they were reminded of a hero, F(1, 196) = 0.08, p = .774, Cohen's d = 0.07, and r = .04 (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The effect of mortality threat and reminders of heroes on unhealthy compensatory consumption—Study 2a

Among the participants who were under the control condition, there were no differences in the intentions to engage in unhealthy compensatory consumption between participants who were reminded of heroes (vs. no‐hero), M HERO = 33.96, SD HERO = 155.71 versus M NO‐HERO = 23.59, SD NO‐HERO = 153.99, F(1, 196) = 0.07, p = .798, Cohen's d = 0.07, and r = .03.

We repeated the analyses controlling for age and gender effects. The results persisted, reconfirming a marginal interaction effect of mortality threat (vs. control) and hero reminder (vs. not) conditions on unhealthy compensatory consumption, F(1, 196) = 2.91, p = .089), while age and gender did not show any significant relation with the intentions to engage in unhealthy compensatory consumption (p > .372).

The results of Study 2a support H1: consumers who experience mortality threats engage in less unhealthy compensatory consumption when they are reminded of heroes (vs. not). Although we find support for our predicted effect in this experimental study, the results of this study are based on an intentional measure. Hence, in Study 2b, we replicate the results of Study 2a using a real behavioral measure.

5. STUDY 2b

In Study 2b, we test for the prediction that when consumers experience mortality threats, reminders of heroes reduce unhealthy compensatory consumption (H1).

We conducted this study in the field in a context where the experience of mortality threat was high. We chose two particular days—the 1st and 2nd of November—to run the study. These 2 days are known as All Saints' Day, the Day of the Dead, and Dia de Muertos, in most Catholic countries (e.g., Italy, Poland, and Mexico), where the 1st of November is an official holiday. On these particular days, people are expected to remember their dead loved ones. As a control condition, we also collected data on the 5th and 6th of November. We randomly assigned participants to the hero (vs. no‐hero) reminder condition and measured unhealthy compensatory consumption. We used a behavioral dependent variable, in which we measured unhealthy compensatory consumption by counting the real amount of unhealthy consumption participants engaged in.

5.1. Participants

Ninety‐six participants (50 male; M = 37.95, SD = 13.90) participated in the field study on the 1st, 2nd, 5th, and 6th of November 2017.

5.2. Materials and procedure

We conducted the study in a major European city on the 1st, 2nd, 5th, and 6th of November 2017. Upon agreement to participate in the study, the participants who participated in the study on the 1st and 2nd of November were asked to indicate the extent to which they were thinking about death in that specific moment and the extent to which they felt that their life was threatened on two different 7‐point scales (1 = Strongly Disagree and 7 = Strongly Agree). The responses to these two questions were highly related; thus, we collapsed them into a single variable—mortality threat manipulation check—with higher ratings indicating higher experience of mortality threat (α = .69). The participants who participated in the study on the 5th and 6th of November responded to these two questions at the end of the survey, as exposure to these questions regarding the fear of death might raise mortality threat (Florian & Mikulincer, 1997).

The participants in the mortality threat condition (i.e., the 1st and 2nd of November) were then asked to recall the All Saints' and Day of Dead festivities and write something about it and how they cope with the fear of death. Sample replies include: “This day reminded me of dear people who do not live anymore, my grandparents for example;” “It is good that we take some time to remember them and visit their graves;” “Death scares me, especially on days like this;” “I hope people will remember me too when I'm not around anymore.” The participants in the control condition were immediately directed to the reminders of the hero (vs. not) condition.

Participants were randomly assigned to the reminders of the hero (vs. no‐hero) condition. In the hero reminder condition, participants thought of a person they considered to be a hero and wrote the reasons for why they considered that particular person to be a hero. Sample replies include: “My hero is my mother. She is the hero of my life because during all her life she tried to fulfill every need of mine, although she was all alone;” “My hero is Angela Merkel. She is a strong and independent woman who now has the power to rule the world and change it for the better.” In the no‐hero reminder condition, the participants were directed to the last part of the study.

In the last part of the study, we offered the participants a bowl of candies to thank them for their participation. We recorded the number of candies (M = 1.14, SD = 1.25) that was consumed by each participant as a measure of unhealthy compensatory consumption. This measurement is in line with previous research suggesting that when participants are exposed to mortality threats, they choose or consume greater amounts of unhealthy food (Ferraro et al., 2005) as a way to compensate for the mortality threat.

5.3. Results and discussion

5.3.1. Manipulation check

As expected, participants who participated in the study on the 1st and 2nd of November scored higher on the mortality threat manipulation check than participants who participated in the study on the 5th and 6th of November, M THREAT = 2.98, SD THREAT = 1.99 versus M CONTROL = 1.65, SD CONTROL = 0.85, t(94) = 3.98, p < .001, Cohen's d = 0.87, and r = .40.

5.3.2. Unhealthy compensatory consumption

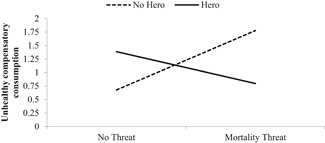

Consistent with H1, ANOVA analyses on intentions to engage in unhealthy compensatory consumption revealed a significant interaction effect of mortality threat (vs. control) and hero (vs. no‐hero) reminder conditions, F(1, 93) = 10.61, p = .002. There was no main effect from the mortality threat (p = .264) or hero reminder (p = .544) conditions on the number of candies consumed. Furthermore, the date (i.e., 1st vs. 2nd of November) of participation in the study had no effect on the unhealthy compensatory consumption of individuals in the mortality threat condition (p = .107).

Consistent with H1, participants in the hero reminder condition engaged in less unhealthy compensatory consumption and hence consumed fewer candies than participants in the no‐hero reminder condition when they participated in the study on the 1st and 2nd of November, M HERO = 0.79, SD HERO = 0.98 versus M NO‐HERO = 1.74, SD NO‐HERO = 1.38, F(1, 93) = 8.98, p = .004, Cohen's d = 0.80, and r = .37. There was no significant difference in the number of candies participants consumed when they were reminded or not reminded of heroes on the 5th and 6th of November, M HERO = 1.32, SD HERO = 1.34 versus M NO‐HERO = 0.67, SD NO‐HERO = 1.02, F(1, 93) = 3.00, and p = .09.

Consistent with previous research, the results also suggest that when participants were not reminded of heroes, the number of candies consumed significantly differed among the participants in the mortality threat and control condition, M THREAT = 1.74, SD THREAT = 1.38 versus M CONTROL = 0.67, SD CONTROL = 1.02, F(1, 93) = 9.74, p = .002, Cohen's d = 0.89, and r = .41), suggesting that consumers who experience mortality threats consume greater numbers of candies as a response to the threat compared to those who do not experience mortality threats when they are not reminded of heroes. However, consistent with our prediction, when participants are reminded of heroes, the number of candies does not differ among participants who are in the mortality threat and control condition, M THREAT = 0.79, SD THREAT = 0.98 versus M CONTROL = 1.32, SD CONTROL = 1.34, F(1, 93) = 2.24, and p = .14 (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The effect of mortality threat and reminders of heroes on unhealthy compensatory consumption—Study 2b

We repeated the analyses controlling for age and gender effects. The results persisted, reconfirming a marginal interaction effect of mortality threat and hero reminder conditions on unhealthy compensatory consumption, F(1, 93) = 9.06, and p = .003, with age not showing any significant relation with unhealthy compensatory consumption (p > .779) and gender showing a marginally significant relation with unhealthy compensatory consumption, F(1, 93) = 4.26, and p = .082.

The results of this study support our prediction that when consumers experience mortality threats, reminders of heroes reduce unhealthy compensatory consumption (H1). Unlike Study 2a and findings from previous research, we did not find a main effect of mortality threats on unhealthy compensatory consumption. We speculate that one of the reasons for this result may be that experiments conducted in the field do not provide evidence as powerful as that in a more controlled setting (Gneezy, 2017; Viglia & Dolnicar, 2020). Although we found support for our predicted effect (H1), the nature of the experiment being in the field with a real behavioral measure may account for the weaker effects we find in Study 2b compared to Study 2a. In Study 3, we test for the role of perceptions of personal power in the relationship between mortality threats and reminders of heroes on unhealthy compensatory consumption.

6. STUDY 3

In Study 3, we test the prediction that perceptions of personal power mediate the effect of hero reminders on unhealthy compensatory consumption when consumers experience mortality threats (H2). As in Study 2b, we conducted the study in a context where mortality threat is high. We conducted the study at a time when the majority of the countries in the world are experiencing the threat of the COVID‐19 pandemic. In the present study, after all the participants reflected on their experience of living with COVID‐19, we randomly assigned them to reminders of hero (vs. no‐hero) conditions. We measured intentions to engage in unhealthy compensatory consumption and perceptions of personal power.

In this study, we also tested for the effects of self‐enhancement needs and body esteem on our predicted effects. Igou et al. (2018) previously found that self‐enhancement needs affect the relationship between people and heroes (e.g., heroic motivations) such that heroic motivations are greater when people have self‐enhancement (i.e., desire to feel good about oneself) needs. Hence, we measured and controlled for the role of self‐enhancement in our study. Moreover, research on food compensatory consumption suggests that body esteem can also play a role in the effect between mortality threats and compensatory consumption (Ferraro et al., 2005; Goldenberg, McCoy, Pyszczynski, Greenberg, & Solomon, 2000). Specifically, respondents with high body esteem reacted less to mortality threats by overeating than those with low body esteem. Therefore, we measured and controlled for the effects of body esteem in this study.

6.1. Participants

Two hundred participants were recruited in the United States using Prolific Academic in return for monetary compensation. One hundred ninety‐two completed the study (94 male, M = 33.15, SD = 11.14).

6.2. Materials and procedure

Participants first reflected on the threatening situation that the world is facing due to the COVID‐19 pandemic by thinking how it has affected over 2 million people all over the world and how over 160,000 have died so far. Given the far‐reaching impact of the global COVID‐19 pandemic at the time of data collection (23rd of April 2020) and the fact that for most people, it is difficult to escape mortality reminders in everyday life (“the threat of death hangs in the air, and many people fear the worst,” Long, 2020, p. 1), we decided that a control condition could not be included in the present study. Hence, all participants were asked to reflect on how the COVID‐19 pandemic situation induces fear of death for them personally.

As a measure of mortality threats, participants were asked to indicate the extent to which they were thinking about death in that specific moment and the extent to which they felt that their life was threatened on two different 7‐point scales (1 = Strongly Disagree and 7 = Strongly Agree). The responses to these two questions were highly related; thus, we collapsed them into a single variable—mortality threats—with higher ratings indicating higher experience of mortality threats (α = .70, M MORTALITY THREAT = 3.94, SD = 1.59).

Next, participants were randomly assigned to either hero or no‐hero reminder conditions (McCabe et al., 2016). As in Study 2a, participants were asked to write about an acquaintance in the no‐hero reminder condition.

We then measured participants' intentions to engage in unhealthy compensatory consumption. We launched the study in a time between breakfast and lunch in the United States. We asked them to imagine having a bowl that they would fill with food that they would want to eat in that particular moment. They were shown six different snacks (i.e., apple, banana, brioche, chocolate cake, cookies, and a fruit smoothie), each accompanied by calorie information. Participants were able to choose more than one snack (please refer to Supporting Information Material for details). As a proxy for intentions to engage in unhealthy compensatory consumption, we calculated the difference between the total calories of the unhealthy snack (i.e., brioche, cookie, chocolate cake) and healthy snack (i.e., apple, banana, fruit smoothie) that participants indicated that they wanted to consume at that moment.

Next, participants completed the perceived power scale using the 8‐item scale from

Anderson and Galinsky (2006) (α = .89). Sample items include “If I want to, I get to make the decisions” and “I think I have a great deal of power” (see Supporting Information Material).

We measured self‐enhancement needs with a 10‐item scale (Hepper, Gramzow, & Sedikides, 2010), which was used in Igou et al. (2018). Sample items include: “Although, in the past I have not been perfect, I think that in general I have positive characteristics and am quite able of achieving something that is exceptional,” “Looking back, I believe that I have been changing, growing, and improving as a person,” and “I believe that I will be happy and successful in the future, more than in the past” (α = .86); see Supporting Information Material. Moreover, we tested for body esteem by asking participants to indicate how they feel about their weight and about their physical appearance using two 5‐point scales (1 = Have strong negative feelings, 2 = Have moderate negative feelings, 3 = Have no feeling one way or the other, 4 = Have moderate positive feelings, 5 = Have strong positive feelings) adapted from Franzoi and Shields (1984) (α = .72).

Finally, as a manipulation check for the hero reminder condition, we asked participants to indicate the extent to which they find the person they wrote about as heroic and the extent to which they find his/her actions as heroic on two 7‐point scales (1 = Strongly Disagree and 7 = Strongly Agree) (α = .97). Given the high value of Cronbach's α, we treated the two items separately.

Finally, participants provided demographic information, and they were thanked.

6.3. Results and discussion

6.3.1. Manipulation check

As intended, participants in the hero reminder condition indicated that they perceive the person they wrote about as more heroic than participants in the no‐hero reminder condition, M HERO = 6.16, SD HERO = 1.00 versus M NO‐HERO = 3.45, SD NO‐HERO = 1.45, t(190) = 14.73, p < .001, Cohen's d = 2.18, and r = .74. Participants in the hero reminder condition also indicated that they perceive the actions of the person they wrote about as more heroic than participants in the no‐hero reminder condition, M HERO = 6.07, SD HERO = 0.94 versus M NO‐HERO = 3.42, SD NO‐HERO = 1.42, t(190) = 14.84, p < .001, Cohen's d = 2.20, and r = .74.

6.3.2. Perceived sense of power

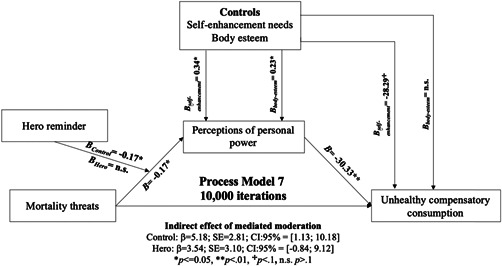

To test the relationship between mortality threats and hero reminders on perceived sense of power, we used a Johnson‐Neyman analysis. We expected that while mortality threats would decrease perceptions of personal power, this effect would not persist for those who are reminded of heroes. The results suggest that mortality threats decrease perceptions of power (B = −.17, SE = 0.07, t = −2.45, p = .012), but the effect does not persist for those reminded of heroes (p = .124) (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

The effect of mortality threats and hero reminders on perceptions of personal power

6.3.3. Test of conditional indirect effects

We next tested the mediating role of perceptions of personal power in the relationship between mortality threats and hero reminders on unhealthy compensatory consumption using a mediated moderation model. We used a mediated moderation model with mortality threats as the independent variable, reminders of heroes as the moderator, perceived personal power as the mediator, and the calories consumed as the dependent variable. We used the Hayes (2013) Model 7 macro with 10,000 bootstrapped samples.

The results reveal that there is no direct effect of mortality threats on unhealthy compensatory consumption (β = −1.28; SE = 6.77; CI 95%: −14.64, 12.08). However, previous research suggests that there need not be a significant direct link between the independent and dependent variable to have an indirect effect (Zhao, Lynch Jr., & Chen, 2010). We also could not find an overall mediated moderation effect (β = −1.73; SE = 3.79; CI 95%: −9.81, 5.75]. However, the conditional indirect effect results reveal that participants who are not reminded of heroes experience greater levels of mortality threats and engage in more unhealthy compensatory consumption through a negative relationship with perceptions of personal power (β CONTROL = 5.18; SE = 2.81; CI 95%: 1.13, 10.18). This relationship does not persist when people are reminded of heroes (β HERO = 3.54; SE = 3.10; CI 95%: −0.84, 9.12; see Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Mediated moderation model of mortality threats, hero reminders, perceptions of personal power, and unhealthy compensatory consumption

We next tested for the role of body esteem and self‐enhancement needs. The results persist when controlling for body esteem (B BODYESTEEM = 0.23, SE = 0.07, t = 3.06, p = .003) and self‐enhancement needs (B SELF‐ENHANCEMENT = 0.34, SE = 0.10, t = 3.30, p = .001). Self‐enhancement needs have a marginal effect on unhealthy compensatory consumption (B SELF ENHANCEMENT = −28.29, SE = 16.01, t = 1.78, p = .079), but body esteem has no effect on unhealthy compensatory consumption, p = .713.

The results also persist when we use the sum of the calories of all the snacks participants would intentionally consume as a proxy for unhealthy compensatory consumption (for brevity, we do not report the results here but can provide them on request). There is no effect of gender (p = .519) or age (p = .152) on any of the predicted models.

The results of Study 3 support our prediction that perceptions of personal power mediate the effect of hero reminders on unhealthy compensatory consumption when consumers experience mortality threats (H2). In this study, we did not find an overall mediated moderation effect. We speculate that the reason why we did not find an overall mediated moderation effect while we found support for the predicted effect (H2) may be because we conducted this study at a time when consumers all around the world are exposed to mortality threats due to the COVID‐19 pandemic. Research shows that the COVID‐19 pandemic has created in people a general fear of death which resides in the air among people of all ages and genders, despite the actual risk that each of them has in getting severally affected by it (Long, 2020). Hence, we speculate that this could have affected the results so that the effect of mortality threats on unhealthy compensatory consumption is not as evident as it would have been when comparing mortality threats condition to a control situation. However, even under these circumstances, the results of this study support our prediction that perceptions of personal power mediate the effect of hero reminders on unhealthy compensatory consumption when consumers experience mortality threats (H2). The results are robust in a context where consumers are experiencing real mortality threats.

7. GENERAL DISCUSSION

From pandemics to terrorist attacks to natural disasters, consumers all around the world are exposed to mortality threats that disrupt the meaning in their lives. Moreover, unhealthy compensatory consumption is employed to cope with the mortality threats that consumers experience. However, there are few insights in marketing literature on how to reduce the unhealthy compensatory consumption of consumers who experience mortality threats. Addressing this study gap, we develop and find robust empirical support to understand how consumers can reduce unhealthy compensatory consumption when they experience mortality threats. We find support for the main effect and the mediating mechanism. The findings from one correlational study and three experimental studies are robust across different mortality threat contexts (e.g., terrorist attacks, Día de Muertos, All Saints Day, or the Day of the Dead, and the COVID‐19 pandemic), and the different responses included intentional and behavioral responses.

As hypothesized, consumers who are reminded of heroes (vs. not) engage in less unhealthy compensatory consumption when they experience a mortality threat. Moreover, perceptions of personal power mediate the effect of mortality threats and reminders of heroes on unhealthy compensatory consumption. We conclude with a discussion of the theoretical contributions of the present research, the managerial implications of the findings, the limitations and the opportunities for further research.

7.1. Theoretical contributions

The findings from this study contribute to the literature on compensatory consumption, mortality threats, and heroes in a number of ways. Previous research on consumer behavior suggests that consumers engage in compensatory consumption and mostly unhealthy compensatory consumption when they experience a mortality threat (Mandel et al., 2017). The results of the present research add to the existing body of literature on compensatory consumption and extend it further by identifying perceptions of personal power as a novel mediator in the relationship between reminders of heroes and coping with psychological threats (in this case, mortality threats). The evidence supporting the role of heroes in boosting perceptions of power and coping responses to psychological threat opens up a range of new opportunities for both scholarly and applied work using heroes to support individuals during times of difficulty.

The findings here show the role that heroes can play in reducing psychological threat, which extends previous literature on consumers who turn to supernatural agents such as angels, devils, jinns, ancestor spirits, and God when they experience a psychological threat (Jong et al., 2012; Kay et al., 2008). This study shows that reminders of heroes (often present in everyday life) do not necessarily have to be supernatural agents and help consumers cope with mortality threats.

Further, contributing to the previous literature on how consumers cope with mortality threats, we suggest that other than building social connections (Wildschut et al., 2006) or time connections (Sarial‐Abi et al., 2017), consumers can cope with psychological threats by enhancing perceptions of personal power. We find support for our hypothesis that perceptions of personal power mediate the effect of mortality threats and reminders of mortality threat on unhealthy compensatory consumption, which extends the literature on mortality threats.

Finally, the results of this study contribute to the growing literature on heroism. While previous research in psychology suggests that heroes help individuals cope with psychological threats (Kinsella, Igou, & Ritchie, 2017), research in psychology lacks empirical evidence on how heroes help individuals cope with threats. The results of this study empirically show that heroes help consumers cope with mortality threats by enhancing perceptions of personal power.

7.2. Practical implications

It is expected that people overeat (i.e., intake a greater‐than‐normal number of calories) during periods of psychological threats, including COVID‐19 lockdowns, as a way to emotionally cope with the psychological threat (Muscogiuri, Barrea, Savastano, & Colao, 2020). The findings here show that inviting people to reflect on their heroes can mitigate the unwanted effects of psychological threats and provide some relief to those experiencing threats. Our findings suggest that both during threatening times related to terrorist attacks and COVID‐19 pandemic, hero reminders can provide some relief to people experiencing mortality threats. By inviting people to reflect on their heroes, policy makers are likely to reduce maladaptive coping methods such as overeating and thus, contribute to public discussion about health during the COVID‐19 pandemic and other sources of public threat in the future. These findings provide an opportunity to highlight heroes as a lost‐cost, immediately available tool for helping others cope with mortality threats.

Relatedly, our findings provide important implications for consumers' welfare and well‐being. Previous research suggests that consumers exposed to mortality threats might be more prone to unhealthy compensatory consumption (Ferraro et al., 2005; Hirschberger, & Ein‐Dor, 2005; Mandel & Smeesters, 2008). This problem may be improved when these consumers experiencing mortality threats are reminded of heroes. The findings of our research suggest that during times when consumers experience mortality threats, being exposed to brands that have images of heroes on product packages or use heroes in brand communications may provide relief to these consumers and consequently reducing intentions for unhealthy compensatory consumption. Further research can also investigate whether hero reminders may also reduce unhealthy compensatory consumption that result from other psychological threats (e.g., social identity threat).

Second, purely from a tactical communications perspective, when mortality threats are high, managers can use heroes in their communications. For example, several brands already use the hero concept in their product and communication strategies. For example, GoPro uses #Heroes hashtag on social media (http://gethashtags.com/instagram/tag/gopro). One of the major target segments of GoPro is people who have active lifestyles and are not afraid of engaging in risky activities (Rose, 2017). We suggest that a positioning based on being a hero when using a GoPro product might mitigate the effects of mortality threats experienced by individuals when engaging in risky, life‐threatening activities.

Third, the findings identify that perceptions of personal power help consumers cope with the negative consequences of mortality threats. Highlighting that consumers have personal power can help them cope with mortality threats.

7.3. Limitations and further research

Our research has some limitations that offer opportunities for further work. First, in this study of how consumers can cope with mortality threats with reminders of heroes, we did not distinguish among different types of heroes. For instance, we did not consider the difference between heroes who are very personal—like a parent, a sibling, a spouse, or some unknown‐by‐the‐masses person (personal hero)—and heroes who are less personal, such as a well‐known figure (cultural hero). We also did not consider whether there are any differences between human and nonhuman (e.g., superheroes) heroes. Further research can examine whether different types of heroes differentially reduce the unhealthy compensatory consumption of consumers who experience mortality threats.

Second, in investigating how to reduce the unhealthy compensatory consumption of consumers when they experience a psychological threat, we mainly focused on mortality threats as a psychological threat that consumers experience. Further research can examine whether the results hold for different types of psychological threats, such as social exclusion, self‐esteem, or social identity threats.

For empirical testing, we had samples mainly from the United States and Europe. Hence, our research does not allow for cultural comparisons or a generalization of results across different cultures. Future research could further investigate the cultural background of individuals and how this affects not only perceptions of heroes but also the virtues of heroes that may have the greatest impact on coping with mortality threats (Green et al., 2017; Kinsella et al., 2017).

8. CONCLUSIONS

In summary, this study provides a useful step in exploring how consumers can reduce unhealthy compensatory consumption when they experience a mortality threat. We propose and find support that reminders of heroes help consumers reduce unhealthy compensatory consumption when they experience a mortality threat by enhancing perceptions of personal power. We hope that this study stimulates further work on the role of heroes in coping with psychological threats in general and mortality threats in particular. We further hope that this study will further extend the research on compensatory consumption, mortality threats, and heroes.

Supporting information

Supporting information

Ulqinaku A, Sarial‐Abi G, Kinsella EL. Benefits of heroes to coping with mortality threats by providing perceptions of personal power and reducing unhealthy compensatory consumption. Psychology & Marketing. 2020;37:1433–1445. 10.1002/mar.21391

This paper is written as part of the dissertation of the first author under the guidance and supervision of the second author.

Footnotes

Unless noted otherwise, we ran the analyses in SPSS Statistics 23 and 25 IBM software. We report effect sizes with partial η 2 Cohen's d and effect‐size correlation r (referred to as r for the rest of the manuscript), where r = d/√(d 2 + 4), as suggested by Becker (2000). The experiments were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Ethical Review Board of the first and second authors' home institutions at the time this study started. All the participants provided their informed consent before participating in the study. None of the participants who completed our studies were excluded from the analyses unless otherwise noted for reasons identified before conducting the research (number of excluded participants reported in each study). No participants were added after the initial analyses were conducted. The attention check consisted of the following: “We want to measure your attention to the questions. If you select 'a lot' now, then it means you are not paying lots of attention and will not be paid; hence, select 'a little' to be paid.” Participants who selected “a lot” were excluded from the analyses.

As a robustness check, we repeated the analyses without the controls, and the results persisted (β = −.96, p < .001).

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data is available upon reasonable request to authors.

REFERENCES

- Allison, S. T. , & Goethals, G. R. (2011). Heroes: What they do and why we need them. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, C. , & Berdahl, J. L. (2002). The experience of power: examining the effects of power on approach and inhibition tendencies. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83(6), 1362–1377. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, C. , & Galinsky, A. D. (2006). Power, optimism, and risk‐taking. European Journal of Social Psychology, 36(4), 511–536. [Google Scholar]

- Arndt, J. , Solomon, S. , Kasser, T. , & Sheldon, K. M. (2004). The urge to splurge: A terror management account of materialism and consumer behavior. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 14(3), 198–212. [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister, R. F. , & Vohs, K. D. (2002). The pursuit of meaningfulness in life. In Snyder C. R. & Lopez S. J. (Eds.), Handbook of positive psychology (pp. 608–618). New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, E. (1973). The denial of death. New York: Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, L. A. (2000). Effect size calculators. Retrieved from http://www.uccs.edu/faculty/lbecker/

- Becker, S. W. , & Eagly, A. H. (2004). The heroism of women and men. American Psychologist, 59(3), 163–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boeuf, B. (2019). The impact of mortality anxiety on attitude toward product innovation. Journal of Business Research, 104, 44–60. [Google Scholar]

- Burke, B. L. , Martens, A. , & Faucher, E. H. (2010). Two decades of terror management theory: A meta‐analysis of mortality salience research. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 14(2), 155–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi, J. , Kwon, K. N. , & Lee, M. (2007). Understanding materialistic consumption: A terror management. Perspective. Journal of Research for Consumers, 13, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- De Clercq, D. , Haq, I. U. , & Azeem, M. U. (2017). Perceived threats of terrorism and job performance: The roles of job‐related anxiety and religiousness. Journal of Business Research, 78, 23–32. [Google Scholar]

- Coughlan, G. , Igou, E. R. , van Tilburg, W. A. , Kinsella, E. L. , & Ritchie, T. D. (2019). On boredom and perceptions of heroes: A meaning‐regulation approach to heroism. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 59(4), 455–473. [Google Scholar]

- Ferraro, R. , Shiv, B. , & Bettman, J. R. (2005). Let us eat and drink, for tomorrow we shall die: Effects of mortality salience and self‐esteem on self‐regulation in consumer choice. Journal of Consumer Research, 32(1), 65–75. [Google Scholar]

- Florian, V. , & Mikulincer, M. (1997). Fear of death and the judgment of social transgressions: A multidimensional test of terror management theory. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 73(2), 369–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folkman, S. , & Lazarus, R. S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York: Springer Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Franco, Z. E. , Blau, K. , & Zimbardo, P. G. (2011). Heroism: A conceptual analysis and differentiation between heroic action and altruism. Review of General Psychology, 15(2), 99–113. [Google Scholar]

- Franco, Z. E. , Efthimiou, O. , & Zimbardo, P. G. (2016). Heroism and eudaimonia: Sublime actualization through the embodiment of virtue. In Vittersø J. (Ed.), Handbook of eudaimonic well‐being, international handbooks of quality‐of‐Life (pp. 337–348). Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Franzoi, S. L. , & Shields, S. A. (1984). The body esteem scale: Multidimensional structure and sex differences in a college population. Journal of Personality Assessment, 48(2), 173–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galinsky, A. D. , Magee, J. C. , Gruenfeld, D. H. , Whitson, J. A. , & Liljenquist, K. A. (2008). Power reduces the press of the situation: Implications for creativity, conformity, and dissonance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95(6), 1450–1466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galinsky, A. D. , Rucker, D. D. , & Magee, J. C. (2015). Power: Past findings, present considerations, and future directions. In Mikulincer M., Shaver P. R., Simpson J. A. & Dovidio J. F. (Eds.), APA handbooks in psychology: APA handbook of personality and social psychology (Vol. 3, pp. 421–460). Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Gill, T. , & Lei, J. (2018). Counter‐stereotypical products: Barriers to their adoption and strategies to overcome them. Psychology & Marketing, 35(7), 493–510. [Google Scholar]

- Gneezy, A. (2017). Field experimentation in marketing research. Journal of Marketing Research, 54(1), 140–143. [Google Scholar]

- Goldenberg, J. L. , McCoy, S. K. , Pyszczynski, T. , Greenberg, J. , & Solomon, S. (2000). The body as a source of self‐esteem: The effect of mortality salience on identification with one's body, interest in sex, and appearance monitoring. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79(1), 118–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green, J. D. , Van Tongeren, D. , Cairo, A. , & Hagiwara, N. (2017). Heroism and the pursuit of meaning. In Allison S. T., Goethals G. R. & Kramer R. M. (Eds.), Handbook of heroism and heroic leadership (Vol. 9, pp. 507–524). New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Han, D. , Duhachek, A. , & Rucker, D. D. (2015). Distinct threats, common remedies: How consumers cope with psychological threat. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 25(4), 531–545. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression‐based approach. New York, NY: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Heine, S. J. , Proulx, T. , & Vohs, K. D. (2006). The meaning maintenance model: On the coherence of social motivations. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 10(2), 88–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hepper, E. G. , Gramzow, R. H. , & Sedikides, C. (2010). Individual differences in self‐enhancement and self‐protection strategies: An integrative analysis. Journal of Personality, 78(2), 781–814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirschberger, G. , & Ein‐Dor, T. (2005). Does a candy a day keep the death thoughts away? The terror management function of eating. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 27(2), 179–186. [Google Scholar]

- Holt, D. B. , & Thompson, C. J. (2004). Man‐of‐action heroes: The pursuit of heroic masculinity in everyday consumption. Journal of Consumer Research, 31(2), 425–440. [Google Scholar]

- Igou, E. R. , van Tilburg, W. , Kinsella, E. L. , & Buckley, L. K. (2018). On the existential road from regret to heroism: Searching for meaning in life. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 2375. 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonas, E. , Schimel, J. , Greenberg, J. , & Pyszczynski, T. (2002). The Scrooge effect: Evidence that mortality salience increases prosocial attitudes and behavior. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 28(10), 1342–1353. [Google Scholar]

- Jong, J. , Halberstadt, J. , & Bluemke, M. (2012). Foxhole atheism, revisited: The effects of mortality salience on explicit and implicit religious belief. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 48(5), 983–989. [Google Scholar]

- Kay, A. C. , Gaucher, D. , Napier, J. L. , Callan, M. J. , & Laurin, K. (2008). God and the government: Testing a compensatory control mechanism for the support of external systems. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95(1), 18–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S. , & Rucker, D. D. (2012). Bracing for the psychological storm: Proactive versus reactive compensatory consumption. Journal of Consumer Research, 39(4), 815–830. [Google Scholar]

- Kinsella, E. L. , Igou, E. R. , & Ritchie, T. D. (2017). Heroism and the pursuit of a meaningful life. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 0022167817701002. [Google Scholar]

- Kinsella, E. L. , Ritchie, T. D. , & Igou, E. R. (2015a). Zeroing in on heroes: A prototype analysis of hero features. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 108(1), 114–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinsella, E. L. , Ritchie, T. D. , & Igou, E. R. (2015b). Lay perspectives on the social and psychological functions of heroes. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lammers, J. , Stoker, J. I. , & Stapel, D. A. (2009). Differentiating social and personal power: Opposite effects on stereotyping, but parallel effects on behavioral approach tendencies. Psychological Science, 20(12), 1543–1548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landau, M. J. , Solomon, S. , Greenberg, J. , Cohen, F. , Pyszczynski, T. , Arndt, J. , & Cook, A. (2004). Deliver us from evil: The effects of mortality salience and reminders of 9/11 on support for President George W. Bush. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 30(9), 1136–1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson, L. R. , & Denton, L. T. (2014). eWOM watchdogs: Ego‐threatening product domains and the policing of positive online reviews. Psychology and Marketing, 31(9), 801–811. [Google Scholar]

- Lash, J. (1995). The hero: Manhood and power. London: Thames and Hudson. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J. , & Smeesters, D. (2010). Have you seen the news today? The effect of death‐related media contexts on brand preferences. Journal of Marketing Research, 47(2), 251–262. [Google Scholar]

- Long, M. (2020). Coronavirus and the fear of death. Retrieved from https://lancasteronline.com/features/together/coronavirus-and-the-fear-of-death-column/article_38d2b5f0-7a74-11ea-9aba-c7fca162b7a5.html

- Mandel, N. , & Heine, S. J. (1999). Terror management and marketing: He who dies with the most toys wins. Advances in Consumer Research, 26, 527–532. [Google Scholar]

- Mandel, N. , Rucker, D. D. , Levav, J. , & Galinsky, A. D. (2017). The compensatory consumer behavior model: How self‐discrepancies drive consumer behavior. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 27(1), 133–146. [Google Scholar]

- Mandel, N. , & Smeesters, D. (2008). The sweet escape: Effects of mortality salience on consumption quantities for high‐and low‐self‐esteem consumers. Journal of Consumer Research, 35(2), 309–323. [Google Scholar]

- Masters, T. , & Mishra, A. (2019). The influence of hero and villain labels on the perception of vice and virtue products. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 29, 428–444. [Google Scholar]

- McCabe, S. , Carpenter, R. W. , & Arndt, J. (2016). The role of mortality awareness in hero identification. Self and Identity, 15(6), 707–726. [Google Scholar]

- Moschis, G. P. (1994). Consumer behavior in later life: Multidisciplinary contributions and implications for research. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 22(3), 195–204. [Google Scholar]

- Muscogiuri, G. , Barrea, L. , Savastano, S. , & Colao, A. (2020). Nutritional recommendations for CoVID‐19 quarantine. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 74, 850–851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennebaker, J. W. , Boyd, R. L. , Jordan, K. , & Blackburn, K. (2015). The development and psychometric properties of LIWC2.

- Proulx, T. , & Inzlicht, M. (2012). The five “A” s of meaning maintenance: Finding meaning in the theories of sense‐making. Psychological inquiry, 23(4), 317–335. [Google Scholar]

- Rose, B. (2017). GoPro is finally starting to right the ship. Retrieved from https://www.outsideonline.com/2232891/gopro-finally-starting-right-ship

- Rosenblatt, A. , Greenberg, J. , Solomon, S. , Pyszczynski, T. , & Lyon, D. (1989). Evidence for terror management theory: I. The effects of mortality salience on reactions to those who violate or uphold cultural values. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57(4), 681–690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi, F. , & Rubera, G. (2018). Measuring competition for attention in social media: NWSL Players on Twitter. Retrieved from https://papers.ssrn.com

- Routledge, C. , Arndt, J. , Wildschut, T. , Sedikides, C. , Hart, C. M. , Juhl, J. , & Schlotz, W. (2011). The past makes the present meaningful: nostalgia as an existential resource. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 101(3), 638–652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruvio, A. , Somer, E. , & Rindfleisch, A. (2014). When bad gets worse: The amplifying effect of materialism on traumatic stress and maladaptive consumption. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 42(1), 90–101. [Google Scholar]

- Sarial‐Abi, G. , Vohs, K. D. , Hamilton, R. , & Ulqinaku, A. (2017). Stitching time: Vintage consumption connects the past, present, and future. . Journal of Consumer Psychology, 27(2), 182–194. [Google Scholar]

- Steele, C. M. , & Aronson, J. (1995). Stereotype threat and the intellectual test performance of African Americans. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69(5), 797–811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan, M. P. , & Venter, A. (2005). The hero within: Inclusion of heroes into the self. Self and Identity, 4(2), 101–111. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, V. L. , Saenger, C. , & Bock, D. E. (2017). Do you want to talk about it? When word of mouth alleviates the psychological discomfort of self‐threat. Psychology & Marketing, 34(9), 894–903. [Google Scholar]

- Tripathy, J. P. (2013). Secondary data analysis: Ethical issues and challenges. Iranian Journal of Public Health, 42(12), 1478–1479. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Dijke, M. , & Poppe, M. (2006). Striving for personal power as a basis for social power dynamics. European Journal of Social Psychology, 36(4), 537–556. [Google Scholar]

- Veen, S. V. , & College, C. (1994). The consumption of heroes and the hero of hierarchy of effects. Advances in Consumer Research, 21(1), 332–336. [Google Scholar]

- Viglia, G. , & Dolnicar, S. (2020). A review of experiments in tourism and hospitality. Annals of Tourism Research, 80, 102858. [Google Scholar]

- Wildschut, T. , Sedikides, C. , Arndt, J. , & Routledge, C. (2006). Nostalgia: Content, triggers, functions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 91(5), 975–993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yousaf, S. , & Xiucheng, F. (2018). Halal culinary and tourism marketing strategies on government websites: A preliminary analysis. Tourism Management, 68, 423–443. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, X. , Lynch, J. G., Jr , & Chen, Q. (2010). Reconsidering Baron and Kenny: Myths and truths about mediation analysis. Journal of Consumer Research, 37(2), 197–206. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting information

Data Availability Statement

Data is available upon reasonable request to authors.