Summary

Haematology patients receiving chemo‐ or immunotherapy are considered to be at greater risk of COVID‐19‐related morbidity and mortality. We aimed to identify risk factors for COVID‐19 severity and assess outcomes in patients where COVID‐19 complicated the treatment of their haematological disorder. A retrospective cohort study was conducted in 55 patients with haematological disorders and COVID‐19, including 52 with malignancy, two with bone marrow failure and one immune‐mediated thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP). COVID‐19 diagnosis coincided with a new diagnosis of a haematological malignancy in four patients. Among patients, 82% were on systemic anti‐cancer therapy (SACT) at the time of COVID‐19 diagnosis. Of hospitalised patients, 37% (19/51) died while all four outpatients recovered. Risk factors for severe disease or mortality were similar to those in other published cohorts. Raised C‐reactive protein at diagnosis predicted an aggressive clinical course. The majority of patients recovered from COVID‐19, despite receiving recent SACT. This suggests that SACT, where urgent, should be administered despite intercurrent COVID‐19 infection, which should be managed according to standard pathways. Delay or modification of therapy should be considered on an individual basis. Long‐term follow‐up studies in larger patient cohorts are required to assess the efficacy of treatment strategies employed during the pandemic.

Keywords: Covid‐19, chemotherapy, risk factors

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19), caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV‐2), was declared a pandemic by the World Health Organisation (WHO) on 12 March 2020 after rapid global spread. 1 COVID‐19 has a varied clinical presentation ranging from asymptomatic/mild infection to life‐threatening illness requiring multi‐organ support. Recognised correlates of poor outcome include age and co‐morbidities such as hypertension, diabetes and coronary artery disease. 1 , 2 The mortality rate of those admitted to hospital in the UK is reported to be 30%, and over 45% in those admitted to intensive care. 2

Preliminary reports suggest that patients with an underlying malignancy have inferior outcomes. 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 While haematology patients are thought to be at increased risk of developing severe complications both due to immune dysfunction from their underlying haematological disorder and immunosuppressive therapies used for treatment, 8 , 9 , 10 delays in treatment of the underling malignancy may compromise patient safety and survival. Data from other cohorts worldwide suggest mortality from COVID‐19 is higher in haematology patients compared to the general population, 3 , 11 , 12 with reported mortality rates between 39% and 50% in other British haematology patient cohorts. 13 , 14 , 15 In particular, a recent UK case series reported significantly higher case fatality rates in haematology patients receiving immunosuppressive or cytotoxic therapy within three months of COVID‐19 diagnosis, raising concerns about the delivery of systemic anti‐cancer therapy (SACT) during the pandemic. 14

There is an ongoing need to share collective experience regarding the clinical course of COVID‐19 in patients with haematological disorders, particularly regarding implications for SACT delivery, in order to enable patients to receive treatment in a timely and safe manner during the pandemic. We describe the outcomes of 55 patients with a haematological diagnosis who were diagnosed with COVID‐19 or tested positive for SARS‐CoV‐2, of which 82% (45/55) were receiving SACT.

Patients and methods

Study design and participants

We studied 55 patients ≥ 18 years old with a haematological disorder who tested positive for SARS‐CoV‐2 or were diagnosed with COVID‐19 based on radiological or clinical criteria, between 20 March and 20 April 2020. Cases were identified through departmental surveillance which identified haematology patients testing positive for SARS‐CoV‐2 or with suspected or confirmed COVID‐19 in outpatient and inpatient departments. Data were censored on 8 May 2020. This cohort included 52 patients with an underlying haematological malignancy, two with bone marrow failure syndromes and one with immune‐mediated thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP) receiving elective immunosuppressive therapy Table I. Patients had laboratory‐confirmed SARS‐CoV‐2 [defined as a positive result on reverse‐transcriptase‐polymerase‐chain‐reaction (RT‐PCR) assay on a combined nose and throat swab specimen] or a high clinical suspicion of COVID‐19 (defined as SARS‐CoV‐2 RT‐PCR‐negative patients who had radiological evidence of pneumonia or an influenza‐like illness in the absence of another identifiable cause). Patient samples were tested using an in‐house assay targeting the N gene of SARS‐CoV‐2. Virology data presented are from combined nose and throat swabs. All laboratory and radiology investigations were performed as part of routine clinical care at the discretion of the treating team. This study was approved by the UK Health Research Authority (HRA) (IRAS number 282997, short title HD‐Covid‐19).

Table I.

Patient demographics, haematological diagnosis and treatment history.

|

All patients n = 55 |

Died n = 19 |

Recovered n = 35 |

OR (95% CI), value |

Severe Disease n = 25 |

No severe disease n = 30 |

OR (95% CI), P‐value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis, median (range) | 63·0 (23–88) | 67·0 (51–88) | 60·0 (23–82) | 1·96 (1·14–3·37), P = 0·015† | 66·0 (27–88) | 59·5 (23–82) | 1·44 (0·95–2·19), P = 0·086 |

| Sex, % (n/total) | |||||||

| Male | 69 (38/55) | 68 (13/19) | 69 (24/35) | 1·00 | 64 (16/25) | 73 (23/30) | 1·00 |

| Female | 31 (17/55) | 32 (6/19) | 31 (11/35) | 1·01 (0·30–3·35), P = 0·99 | 36 (9/25) | 27 (8/30) | 1·55 (0·49–4·88), P = 0·46 |

| Ethnicity, % (n/total | |||||||

| Caucasian | 70 (38/54) | 53 (10/19) | 79 (27/34) | 1·00, P = 0·039† | 60 (15/25) | 79 (23/29) | 1·00, P = 0·13 |

| Black | 9 (5/54) | 21 (4/19) | 3 (1/34) | 6·40 (0·65–62·84) | 16 (4/25) | 3 (1/29) | 11·20 (1·11–112·52) |

| Asian | 19 (10/54) | 26 (5/19) | 15 (5/34) | 2·40 (0·58–9·93) | 24 (6/25) | 14 (4/29) | 2·80 (0·67−11·75) |

| Other | 2 (1/54) | 0 | 3 (1/34) | – | 0 | 3 (1/29) | ‐ |

| Smoker, % (n/total) | |||||||

| Non‐smoker | 82 (31/38) | 86 (12/14) | 78 (18/23) | P > 0·99* | 87 (14/16) | 77 (17/22) | P 1 = 0·82 |

| Current | 3 (1/38) | 0 | 4 (1/23) | 0 | 5 (1/22) | ||

| Ex‐smoker | 16 (6/38) | 14 (2/14) | 17 (4/23) | 12 (2/16) | 18 (4/22) | ||

| BMI, median (range) | 25·7 (18–40·5) | 24·3 (18·2–31) | 26·7 (18–40·5) | 0·33 (0·09–1·25), P = 0·10 | 25·8 (18·2–37·6) | 25·7 (18–40·5) | 0·61 (0·20–1·91), P = 0·40 |

| Comorbidities and ceiling of care | |||||||

| COPD, % (n/total) | |||||||

| No COPD | 98 (53/54) | 95 (18/19) | 100 (34/34) | P = 0·36* | 96 (24/25) | 100 (29/29) | P = 0·46* |

| COPD | 2 (1/54) | 5 (1/19) | 0 | 4 (1/25) | 0 | ||

| Ischaemic heart disease, % (n/total) | |||||||

| No IHD | 94 (51/54) | 100 (19/19) | 91 (31/34) | P = 0·55* | 96 (24/25) | 93 (27/29) | P > 0·99* |

| IHD | 6 (3/54) | 0 | 9 (3/34) | 4 (1/25) | 7 (2/29) | ||

| Hypertension, n (%) | |||||||

| No hypertension | 63 (34/54) | 68 (13/19) | 60 (21/35) | 1·00 | 68 (17/25) | 60 (18/30) | 1·00 |

| Hypertension | 37 (20/54) | 32 (6/19) | 40 (14/35) | 0·69 (0·21–2·25), P = 0·54 | 32 (8/25) | 40 (12/30) | 0·71 (0·23–2·15), P = 0·54 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | |||||||

| No diabetes | 80 (43/54) | 84 (16/19) | 76 (26/34) | 1·00 | 80 (20/25) | 79 (23/29) | 1·00 |

| Diabetes | 20 (11/54) | 16 (3/19) | 24 (8/34) | 0·61 (0·14– 2·64), P = 0·51 | 20 (5/25) | 21 (6/29) | 0·96 (0·25–3·62), P = 0·95 |

| Chronic kidney disease, n (%) | |||||||

| No CKD | 87 (47/54) | 89 (17/19) | 85 (29/34) | 1·00 | 84 (21/25) | 90 (26/29) | 1·00 |

| CKD | 13 (7/54) | 11 (2/19) | 15 (5/34) | 0·68 (0·12‐ 3·91), P = 0·67 | 16 (4/25) | 10 (3/29) | 1·65 (0·33–8·21), P = 0·54 |

| Haematology diagnosis, % (n/total) | |||||||

| MM/AL | 24 (13/55) | 21 (4/19) | 26 (9/35) | .. | 16 (4/25) | 30 (9/30) | .. |

| MDS | 7 (4/55) | 5 (1/19) | 9 (3/35) | .. | 4 (1/25) | 10 (3/30) | .. |

| Acute leukaemia | 20 (11/55) | 16 (3/19) | 20 (7/35) | .. | 24 (6/25) | 17 (5/30) | .. |

| CML | 2 (1/55) | 0 | 3 (1/35) | .. | 4 (1/25) | 0 | .. |

| B‐cell NHL low grade | 15 (8/55) | 16 (3/19) | 14 (5/35) | .. | 16 (4/25) | 13 (4/30) | .. |

| B‐cell NHL high grade | 16 (9/55) | 21 (4/19) | 14 (5/35) | .. | 16 (4/25) | 17 (5/30) | .. |

| BM failure syndromes | 4 (2/55) | 5 (1/19) | 3 (1/35) | .. | 4 (1/25) | 3 (1/30) | .. |

| TTP | 2 (1/55) | 0 | 3 (1/35) | .. | 0 | 3 (1/30) | .. |

| MPN | 11 (6/55) | 16 (3/19) | 9 (3/35) | .. | 16 (4/25) | 7 (2/30) | .. |

| Prior lines of therapy (Number), n (%) | |||||||

| 0 | 64 (35/55) | 58 (11/19) | 69 (24/35) | .. | 60 (15/25) | 67 (20/30) | .. |

| 1 | 13 (7/55) | 11 (2/19) | 11 (4/35) | .. | 16 (4/25) | 10 (3/30) | .. |

| 2 | 16 (9/55) | 26 (5/19) | 11 (4/35) | .. | 20 (5/25) | 13 (4/30) | .. |

| 3 | 4 (2/55) | 5 (1/19) | 3 (1/35) | .. | 4 (1/25) | 3 (1/30) | .. |

| 4 | 4 (2/55) | 0 | 6 (2/35) | .. | 0 | 7 (2/30) | .. |

| Stem cell transplant, n (%) | |||||||

| No ASCT | 83 (45/54) | 84 (16/19) | 85 (29/34) | .. | 84 (21/25) | 83 (24/29) | .. |

| AutoSCT | 13 (7/54) | 16 (3/19) | 9 (4/34) | .. | 12 (3/25) | 14 (4/29) | .. |

| AlloSCT | 4 (2/54) | 0 | 3 (1/34) | .. | 4 (1/25) | 3 (1/30) | .. |

| Immunosuppression within 14 days, n (%) | |||||||

| No immunosuppression | 53 (28/53) | 44 (8/18) | 59 (20/34) | 1·00 | 50 (12/24) | 55 (16/29) | 1·00 |

| Immunosuppression | 47 (25/53) | 56 (10/18) | 41 (14/34) | 1·79 (0·56–5·66), P = 0·32 | 50 (12/24) | 45 (13/29) | 1·23 (0·42–3·64), P = 0·71 |

| Days since chemo day 1, n (%) | |||||||

| ≥28 days since chemo day 1 | 18 (10/55) | 11 (2/18) | 25 (8/34) | 1·00 (P = 0·43) | 12 (3/25) | 23 (7/30) | 1·00 (P = 0·48) |

| 14‐28 days since chemo day 1 | 24 (13/55) | 26 (5/18) | 22 (7/34) | 2·86 (0·42–19·65) | 25 (6/25) | 23 (7/30) | 2·00 (0·35–11·36) |

| <14 days since chemo day 1 | 53 (29/55) | 63 (12/18) | 53 (17/34) | 2·82 (0·51–15·72) | 62 (15/25) | 47 (14/30) | 2·50 (0·54–11·62) |

| No treatment | 5 (3/55) | 0 | 3 (9/34) | .. | 4 (1/25) | 7 (2/30) | ‐ |

| Intensity of most recent treatment, n (%) | |||||||

| Non‐intensive | 65 (36/55) | 74 (14/19) | 63 (22/35) | 1·00 | 64 (16/25) | 67 (20/30) | 1·00 |

| Intensive | 29 (16/55) | 26 (5/19) | 29 (10/35) | 0·79 (0·22–2·79), P = 0·71 | 32 (8/25) | 27 (8/30) | 1·25 (0·38–4·07), P = 0·71) |

| No treatment | 5 (3/55) | 0 | 9 (3/35) | 4 (1/25) | 7 (2/30) | ||

BMI, body mass index; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; IHD, ischaemic heart disease; CKD, chronic kidney disease; autoSCT, autologous stem cell transplant; alloSCT, allogeneic stem cell transplant; chemo, chemotherapy.

Fisher's exact test used to calculate differences between patient groups.

denotes a significant P value (<0·05).

Statistical analysis

Logistic regression was used to compare the risk of developing severe disease [WHO ordinal score ≥ 5; non‐invasive ventilation (NIV) or invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV), or death] or the risk of death, for different baseline characteristics (all analyses are detailed in Tables I and II, Table SI). Duration of viral shedding was analysed using Kaplan–Meier methods, with time until resolution measured from the date of symptom onset until the first negative swab. Patients without a negative swab were censored at the time of the last positive swab. Only patients who recovered were included within this analysis. All analyses were performed using STATA version 15·1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

Table II.

COVID‐19 diagnosis and symptoms.

|

All patients n = 55 |

Died n = 19 |

Recovered n = 35 |

OR (95% CI), P value |

Severe Disease n = 25 |

No severe disease n = 30 |

OR (95% CI), P‐value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Days from symptoms to presentation | 4 (0–28) | 3 (0–14) | 4 (0–28) | .. | 4 (0–20) | 4 (0–28) | .. |

| COVID presentation, % (n/total) | |||||||

| Outpatient | 15 (8/55) | 5 (1/19) | 20 (7/35) | .. | 8 (2/25) | .. | .. |

| Inpatient | 86 (47/55) | 95 (18/19) | 80 (28/35) | .. | 92 (23/25) | .. | .. |

| Swab positive, % (n/total) | |||||||

| No | 13 (7/55) | 16 (3/19) | 11 (4/35) | .. | 12 (3/25) | .. | .. |

| Yes | 87 (48/55) | 84 (16/19) | 89 (31/35) | .. | 88 (22/25) | .. | .. |

| Method of diagnosis, % (n/total) | |||||||

| Nose and throat swab | 80 (44/55) | 79 (15/19) | 80 (28/35) | .. | 80 (20/25) | .. | .. |

| Radiological | 16 (9/55) | 21 (4/19) | 14 (5/35) | .. | 20 (5/25) | .. | .. |

| Clinical | 4 (2/55) | 0 | 6 (2/35) | .. | 0 | .. | .. |

| Highest fever recorded | 38·5 (37–40·5) | 38·5 (37–40·5) | 38·5 (37–40·2) | .. | 38·8 (37–40·5) | 38·4 (37–40) | .. |

| Fever ≥ 38, % (n/total) | |||||||

| No fever | 19 (9/47) | 22 (4/18) | 18 (5/28) | 1·00 | 17 (4/24) | 22 (5/23) | 1·00 |

| Fever | 81 (38/47) | 78 (14/18) | 82 (23/28) | 0·76 (0·17–3·32), P = 0·72 | 83 (20/24) | 78 (18/23) | 1·39 (0·32–5·99), P = 0·66 |

| Cough, % (n/total) | |||||||

| No cough | 30 (16/53) | 17 (3/18) | 38 (13/34) | 1·00 | 17 (4/24) | 41 (12/29) | 1·00 |

| Cough | 70 (37/53) | 83 (15/18) | 62 (21/34) | 3·10 (0·75–12·80), P = 0·12 | 83 (20/24) | 59 (17/29) | 3·53 (0·96−12·99), P = 0·058 |

| Sputum, % (n/total) | |||||||

| No sputum | 83 (44/53) | 78 (14/18) | 88 (30/34) | 1·00 | 75 (18/24) | 90 (26/29) | 1·00 |

| Sputum | 17 (9/53) | 22 (4/18) | 12 (4/34) | 2·14 (0·47, 9·84), P = 0·33 | 25 (6/24) | 10 (3/29) | 2·89 (0·64−13·08), P = 0·17 |

| Myalgia, % (n/total) | |||||||

| No myalgia | 89 (47/53) | 100 (18/18) | 82 (28/34) | P = 0·081* | 92 (22/24) | 86 (25/29) | 1·00 |

| Myalgia | 11 (6/53) | 0 | 18 (6/34) | 8 (2/24) | 14 (4/29) | 0·57 (0·09–3·41), P = 0·54 | |

| Fatigue, % (n/total) | |||||||

| No fatigue | 53 (28/53) | 44 (8/18) | 59 (20/34) | 1·00 | 33 (8/24) | 69 (20/29) | 1·00 |

| Fatigue | 47 (25/53) | 56 (10/18) | 41 (14/34) | 1·79 (0·56–5·66), P = 0·32 | 68 (16/24) | 31 (9/29) | 4·44 (1·40−14·14), P = 0·012† |

| Dyspnoea, % (n/total) | |||||||

| No dyspnoea | 39 (20/51) | 24 (4/17) | 48 (16/33) | 1·00 | 22 (5/23) | 54 (15/28) | 1·00 |

| Dyspnoea | 61 (31/51) | 77 (13/17) | 51 (17/33) | 3·06 (0·82–11·36), P = 0·095 | 78 (18/23) | 46 (13/28) | 4·15 (1·20−14·33), P = 0·024† |

| Diarrhoea, % (n/total) | |||||||

| No | 81 (43/53) | 83 (15/18) | 82 (15/18) | 1·00 | 79 (19/23) | 83 (24/29) | 1·00 |

| Yes | 19 (10/53) | 17 (3/18) | 18 (3/18) | 0·93 (0·20–4·27), P = 0·93 | 21 (5/23) | 17 (5/29) | 1·26 (0·32–5·01), P = 0·74 |

| Other infection present‡, % (n/total) | |||||||

| No | 37 (20/55) | 37 (7/19) | 37 (13/35) | 1·00 | 32 (8/25) | 40 (12/30) | 1·00 |

| Possible bacterial | 33 (18/55) | 32 (6/19) | 31 (11/35) | 1·01 (0·32–3·22), P = 0·98 | 40 (10/25) | 27 (8/30) | 1·42 (0·47–4·31), P = 0·54 |

| Confirmed bacterial | 31 (17/55) | 32 (6/19) | 31 (11/35) | 28 (7/25) | 33 (10/30) | ||

| Chest X‐ray performed, % (n/total) | |||||||

| No CXR | 4 (2/50) | 6 (1/18) | 3 (1/31) | .. | 4 (1/24) | 4 (1/26) | .. |

| CXR | 96 (48/50) | 94 (17/18) | 97 (30/31) | .. | 96 (23/24) | 96 (25/26) | .. |

| Chest X‐ray findings, % (n/total) 2 | |||||||

| Clear | 17 (8/47) | 12 (2/16) | 21 (6/29) | 1·00 (P = 0·083) | 13 (3/23) | 21 (5/24) | 1·00 (P = 0·33) |

| Bilateral interstitial infiltrates | 53 (25/47) | 65 (11/16) | 45 (13/29) | 3·38 (0·59–19·38) | 70 (16/23) | 38 (9/24) | 3·38 (0·59–19·38) |

| Other infective findings | 26 (12/47) | 24 (4/16) | 28 (8/29) | 2·00 (0·28–14·20) | 17 (4/23) | 33 (8/24) | 2·00 (0·28–14·20) |

| Other, non‐infective findings | 4 (2/47) | 0 | 7 (2/29) | 0 | 8 (2/24) | ||

| CT Scan, % (n/total) | |||||||

| No CT scan | 71 (34/48) | 71 (12/17) | 73 (22/30) | .. | 65 (15/23) | 76 (19/25) | .. |

| CT scan performed | 29 (14/48) | 29 (5/17) | 27 (8/30) | .. | 35 (8/23) | 24 (6/25) | .. |

| CT scan findings, % (n/total) | |||||||

| Ground glass | 71 (10/14) | 80 (4/5) | 75 (6/8) | .. | 75 (6/8) | 67 (4/6) | .. |

| Nodular changes | 7 (1/14) | 0 | 0 | .. | 12 (1/8) | 0 | .. |

| Others | 21 (3/14) | 20 (1/5) | 25 (2/8) | .. | 12 (1/8) | 33 (2/6) | .. |

Other, non‐infective findings on chest X‐ray (CXR) group with clear X‐ray for regression analysis.

Fisher's exact test used to calculate differences between patient groups.

denotes a significant result (P < 0·05).

Possible infection and confirmed infection grouped for regression analysis.

Results

Demographics and clinical characteristics

Fifty‐five patients were identified, of whom 93% (51/55) required hospital admission including 11% (6/55) receiving cancer care at UCLH but admitted to other centres; 7% (4/55) were managed as outpatients. Among patients requiring hospital admission 86% (44/51) were on SACT at the time of COVID‐19 diagnosis, 87% (48/55) had a laboratory‐confirmed diagnosis of COVID‐19, 9% (5/55) were diagnosed based on radiological appearances on a plain chest radiograph (CXR) or computed tomography (CT), while 4% (2/55) had indeterminate radiology but a highly suggestive clinical picture of COVID‐19. Median age at time of COVID‐19 diagnosis was 63 (range 23–88) years, and 67% (37/55) were male. Patients had a variety of haematological diagnoses, of which 52 (95%) were malignant conditions (Table I).

Patient presentation

A diagnostic swab was taken from 85% (47/55) of patients as an inpatient or in the Emergency Department, and 15% (8/55) were tested as outpatients. Of these, 80% presented with fever and 70% had a cough (Table II). Four patients were admitted with symptoms including cough and fever but were found to be pancytopenic and a new diagnosis of acute leukaemia/myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) was made [two acute myeloid leukaemia (AML), one B‐cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (B‐ALL), one high‐risk MDS] with concomitant COVID‐19. Two patients were admitted to hospital for management of their haematological malignancy and were asymptomatic or had mild symptoms of COVID‐19. Both these patients underwent testing for SARS‐CoV‐2 infection due to possible infective contacts and/or hospital infection control policy. Four patients had been in hospital for greater than seven days before they developed symptoms and thus likely acquired COVID‐19 in hospital. Four patients were neutropenic (neuts < 1 × 109/l) at time of COVID‐19 diagnosis. Thirteen percent (7/55) developed neutropenia (<1 × 109/l) in the seven days following COVID‐19 diagnosis.

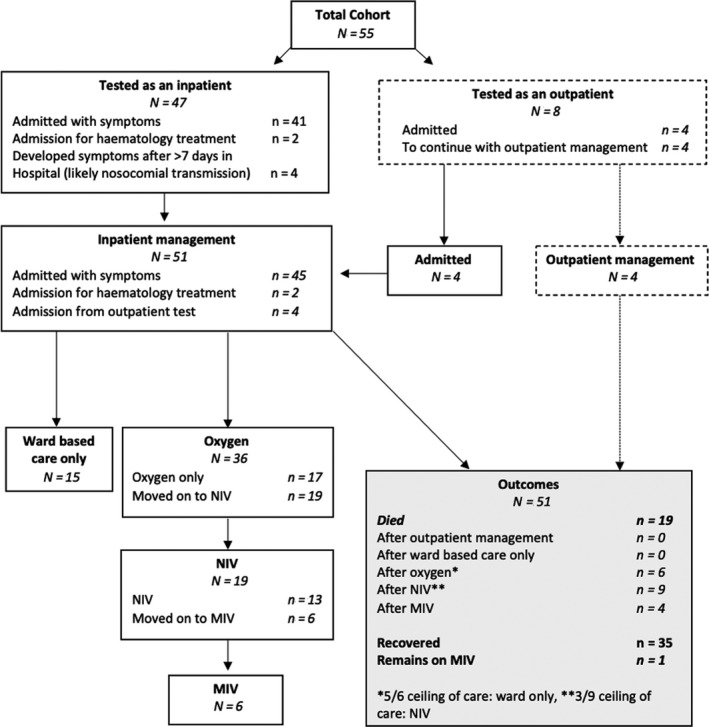

Outcomes and clinical course

Sixty‐four percent (35/55) of patients recovered, 35% (19/55) died and one patient remained on mechanical ventilation 33 days from diagnosis. Clinical course, respiratory support requirements and outcomes are detailed in Fig 1 and Table III. Median follow‐up in recovered patients was 27 days (range 17–43). Mortality in hospitalised patients was 37% (19/51). Thirty‐seven percent (19/51) required NIV; of these 13 (68%) died, four (21%) recovered, and one (5%) recovered after NIV and a period of IMV. Six (32%) who received NIV subsequently required IMV. In patients who recovered after NIV therapy alone, median duration of NIV was five days (range 4–8). Four of the 19 patients who required NIV or IMV survived (one recovering in hospital and one still ventilated at time of data censor). The mortality rate for those requiring invasive ventilation was 66% (4/6; Fig 1). Treatment escalation plans were used to define ceilings of care in 96% (53/55) of patients. Among these, 42% (32/55) were to receive intubation and cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) in the event of clinical deterioration, while 43% (23/55) were not (Table III).

Fig 1.

Consort diagram.

Table III.

COVID‐19 therapies and clinical outcomes.

| COVID‐19 therapies and clinical outcomes | n = 55 |

|---|---|

| Thrombotic event/anticoagulation | % (n/total) |

| Admission anticoagulation* | |

| Prophylactic low molecular weight heparin | 58% (26/45) |

| Therapeutic dose low molecular weight heparin | 13% (6/45) |

| Direct oral anticoagulants | 7% (3/45) |

| Thrombotic events | |

| Deep vein thrombosis | 5% (3/55) |

| Pulmonary embolism | 5% (3/55) |

| PICC‐associated superficial thrombophlebitis | 2% (1/55) |

| ICU/HDU level therapy | % (n/total) |

| CPAP | 35% (19/55) |

| Endotracheal intubation | 11% (6/55) |

| Renal replacement therapy | 2% (1/53) |

| Vasopressors | 10% (5/55) |

| Treatment escalation plans: | % (n/total) |

| Full escalation | 58·1% (32/55) |

| Escalation to NIV only | 29·1% (16/55) |

| Ward based therapies only | 12·7% (7/55) |

| DNACPR in place | 41·8% (23/55) |

| Outcomes | Days (range) |

| Median length of stay: | |

| In hospital | 13 (0–135) |

| In ICU | 7 (1–32) |

| Median duration of: | |

| CPAP | 4 (1–15) |

| % (n/total) | |

| Died in hospital | 35% (19/55) |

| Discharged from hospital | 64% (35/55) |

| Restarted haematological cancer‐directed therapy | 52% (14/27) |

FiO2, fraction of inspired oxygen; ICU, intensive care unit; HDU, high dependency unit; CPAP, continuous Positive Airway Pressure; DNACPR, do not attempt cardiopulmonary resuscitation; NIV, non‐invasive ventilation; PCR, polymerase chain reaction.

Data regarding baseline anticoagulation missing in 6/51 hospitalised patients.

Risk factors for severe disease/mortality

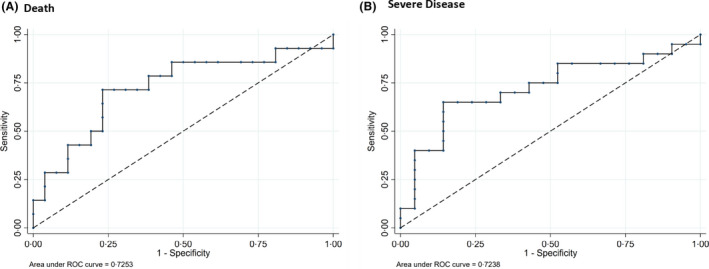

High C‐reactive protein (CRP) levels at clinical presentation were significantly associated with an increased risk of severe disease and death, with CRP ≥ 100 mg/l translating to a markedly increased risk of severe disease, (overall rersponse [OR] 5·94 [1·52, 23·18], P = 0·010) and death (OR: 5·63 [1·35, 23·45], P = 0·018). Receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curve analysis confirmed that baseline CRP conferred a high sensitivity and specificity for both risk of disease severity and death (Fig 2). No other haematological or biochemical parameters at diagnosis showed an increased risk of disease severity or death (Table SI).

Fig 2.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis of C‐reactive protein. (A) Death; for a cut‐off of 100, sensitivity 71·5% and specificity 65·4%. (B) Severe disease; for a cut‐off of 100, sensitivity 65·0% and specificity 71·4%.

Age was significantly associated with mortality, almost doubling the risk of death for each 10‐year increase: {odds ratio (OR) 1·96, 95% CI [1·14, 3·37], P = 0·015}. An increased risk of severe disease was observed in older patients, although this did not reach significance: (OR 1·44 [0·95, 2·19], P = 0·086). Ethnicity was significantly associated with an increased risk of death, with black patients having an 11‐fold increased mortality risk compared to Caucasian patients (P = 0·039). None of the previously reported co‐morbidities associated with adverse risk such as hypertension or diabetes were significant in this cohort, nor was the presence of multiple adverse risk factors.

Impact of COVID‐19 on choice and delivery of SACT

At the time of COVID‐19 diagnosis, 94% (52/55) of patients were currently on or had previously received SACT.

Forty‐five (82%) patients testing positive for SARS‐CoV‐2 had received SACT within 28 days of their diagnosis (Table I). Of those who were currently on or had recently received SACT, 65% (34/52) had their therapy modified by dose change (n = 1), treatment delay (n = 28) and/or a change in treatment regimen (n = 5) due to concerns regarding the administration of standard chemotherapy during the COVID‐19 pandemic and in line with national guidance. 16 No therapy regimens were associated with an increased risk of disease severity or death although patient numbers in these groups were small.

A new haemato‐oncology diagnosis requiring treatment coincided with a positive SARS‐CoV‐2 PCR result in 7% (4/55) of patients. Venetoclax plus azacitadine were used as induction treatment for one patient with AML and one with high‐risk MDS. One patient received gilteritinib (based on FLT3 mutation) as induction treatment for AML. 17 These regimens were felt to be less myelosuppressive compared to standard therapy. 18 , 19 A patient with a new diagnosis of Philadelphia‐positive B‐ALL and a mild clinical presentation of COVID‐19 underwent reduced‐intensity imatinib‐based induction therapy on the UKALL60+ protocol. 20 All four patients recovered from COVID‐19 despite undergoing induction therapy during their illness.

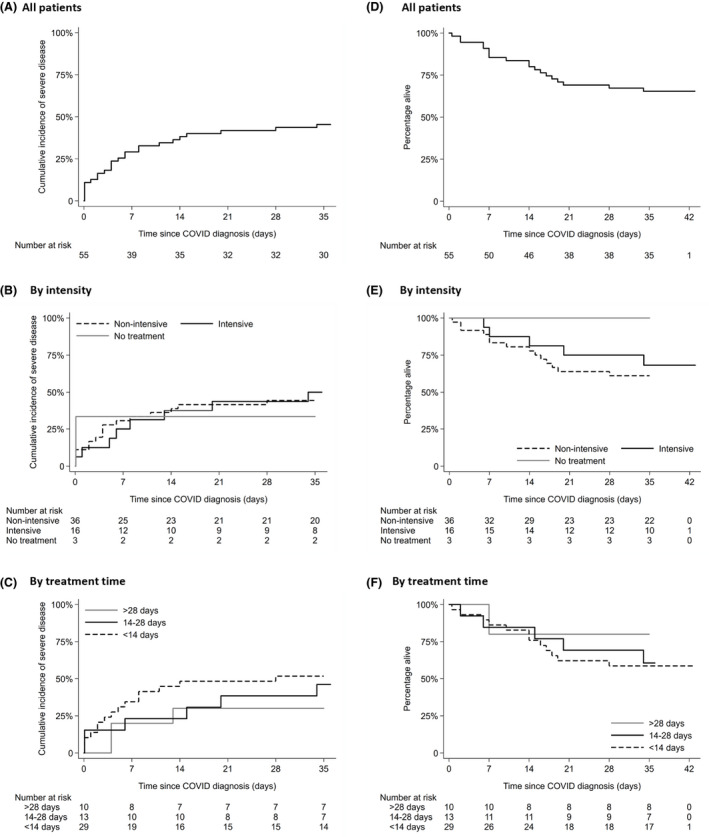

Timing of SACT therapy and regimen intensity was also assessed. While we saw higher numbers of severe disease and death for those treated within 28 days, these did not reach statistical significance (Table I, Fig 3). Intensity of therapy regimen did not appear to increase the risk of developing severe disease (Fig 3, Table SII). Receiving steroids as part of SACT or for graft versus host disease (GVHD) did not significantly affect outcomes in this cohort either.

Fig 3.

Cumulative incidence of event (severe disease) for (A) whole cohort, (B) by treatment group (intensive/non‐intensive) and (C) by treatment time. Patients who had recovered without severe disease were recorded as not having an event and last follow‐up time was censored at day 35 (the day after last reported COVID severe event in the cohort). (D) Kaplan–Meier survival curve of the whole cohort, (E) treatment intensity and (F) treatment time. Patients who had recovered were censored at day 35 (the day after the last reported COVID death). [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Seven out of 55 patients (12%) had previously undergone autologous stem cell transplant (autoSCT). One autoSCT patient was diagnosed with COVID‐19 within 28 days of administration of stem cells and died on day 28 post stem cell infusion after receiving NIV. All other autoSCT patients had received stem cell infusion >6 months prior to COVID‐19 diagnosis. Of the seven autoSCT patients, three (43%) died.

Four percent (2/55) of the total cohort had previously undergone allogeneic stem cell transplantation (alloSCT) and both had received stem cell infusion in the six months prior to COVID‐19 diagnosis (one within 28 days), and were being treated for GVHD at the time of infection. One patient died and the other remains on invasive ventilation at time of data censor.

Microbiological and virological results

In all, 86% (43/50) of patients received systemic antibiotics, and 6% (3/50) antifungal therapy during their COVID‐19 illness. A number of patients had other concomitant infections diagnosed during their COVID‐19 admission (Table SIII). Thus, 6% (3/49) demonstrated concomitant viral infections [rhinovirus and influenza A (n = 1), metapneumovirus (n = 1), adenovirus (n = 1)]. The median duration of SARS‐CoV‐2 viral shedding in recovered patients was 34 days (27 patients, 95% CI 27–47). The longest duration of shedding in a recovered patient still positive at the time of data censure was 49 days. The time to negative swab was not prolonged in patients treated with chemo‐ or immunotherapy in the last 14 or 28 days.

Thromboembolic prophylaxis and events

Of inpatients, 78% (35/45) received anticoagulation at admission: 58% (26/45) received prophylactic dose low‐molecular‐weight heparin (LMWH), while 20% (9/45) received therapeutic anticoagulation (six LMWH, three direct oral anticoagulants) for pre‐existing indications. Thrombocytopenia occurred in 18% (7/45), precluding LMWH administration.

The overall rate of venous thromboembolism (VTE) following COVID‐19 diagnosis was 13% (7/55): three with pulmonary emboli, three with deep‐vein thromboses [one associated with a peripheral‐inserted central venous catheter (PICC), and one with PICC‐associated superficial thrombophlebitis]. These were identified at a median of five days (range 1–12) from COVID‐19 diagnosis. Among thrombotic events, 71% (5/7) were diagnosed while on LMWH (four receiving prophylactic dose and one treatment dose). Adjustment or omission of their prophylactic/treatment LMWH was required in 57% (26/46) of inpatients, including 28% (13/46) due to thrombocytopenia, and 2% (1/46) due to bleeding. One intensive‐care patient with underlying myeloproliferative neoplasm (MPN) suffered embolic digital ischaemia, with no other arterial events reported.

Clinical trials and experimental drugs

Of the SARS‐CoV‐2 RT‐PCR‐positive haematology cohort at our centre, 8% (4/48) were successfully recruited into COVID‐19 clinical trials. Two patients with clinical and biochemical features of hyper‐inflammation were treated with the interleukin‐1 receptor antagonist anakinra off trial (before clinical trials of immunomodulatory drugs were open). One made a gradual recovery with a progressive reduction in temperature, oxygen demand and inflammatory markers over a 10‐day period, allowing weaning of anakinra and discharge from hospital; the other remains ventilated at the time of data censor.

Discussion

We report the outcomes of a large cohort of haematology patients with COVID‐19, the majority of whom were receiving SACT. Despite valid concerns regarding the vulnerability of haematology patients to COVID‐19, our observed mortality of 37% in hospitalised patients indicates that a significant proportion of haematology patients recover from COVID‐19, despite recent or concurrent SACT. Despite heterogeneity in our patient cohort and methodology, the mortality rate described here is consistent with those from other UK cohorts of patients with haematological malignancy and COVID‐19 (39–52%). 13 , 14 , 15 While a direct comparison with a non‐haematology cohort has not been performed, our data corroborate existing studies that haematology patients are at increased risk of severe disease and mortality from COVID‐19, with a large UK population study reporting lower mortality of 33% of all hospitalised cases, despite an older median study age of 72 years. 2 Several risk factors for severe COVID‐19 in the general population are relevant to patients with haematological disorders. 21 Each 10‐year increase in age corresponded to a doubling in risk of death, while black patients had an 11‐fold increase in risk of death compared to Caucasian patients. Patients with respiratory symptoms (cough and dyspnoea), patient‐reported fatigue at diagnosis and raised CRP at presentation were also associated with an increased risk of severe disease or mortality. These risk factors may help identify patients requiring admission for clinical monitoring and those that can be advised to self‐isolate in the community with supervised remote review.

In this patient cohort, 81% had SACT modifications (delay or de‐intensification) in light of their COVID‐19 diagnosis, including when receiving induction treatment for new diagnoses of haematological malignancies, in line with emerging evidence and guidance. 22 While patients who received SACT within 28 days of COVID‐19 diagnosis had higher rates of severe disease and mortality, this was not statistically significant, although analysis is limited by the size and heterogeneity of the cohort. While a recent UK series has suggested that recent SACT confers a higher risk of death from COVID‐19 in haemato‐oncology patients, 14 two recent multicentre cohort studies including haematology patients have found no impact of SACT timing on COVID‐19 outcome, 23 , 24 highlighting the need for further data regarding the implications for different disease subtypes and treatment modalities. While caution in instituting SACT is clearly warranted, our data suggest that modification of therapy including the use of non‐standard treatment regimens can be considered in haematology patients with COVID‐19 to allow treatment of the haematological diagnosis while accepting risks of COVID‐19 infection. Indeed, our experience of patients with newly diagnosed leukaemias and active SARS‐CoV‐2 infection also demonstrates that, where urgently indicated, SACT may be safely delivered in this setting, emphasising that referral of new diagnoses to specialist treating centres for prompt initiation of lifesaving SACT should not be delayed. Where the COVID‐19 pandemic has forced a paradigm shift in therapy, the long‐term follow‐up of these patients will be crucial to assess efficacy in comparison to more intensive chemotherapy‐based regimens. Furthermore, the cases of newly diagnosed leukaemia highlight the importance of COVID‐19 testing as part of routine investigation of patients with haematological malignancies in the current climate. 25 Both patients in our cohort had mild symptoms, suggesting that patients undergoing SACT may still have asymptomatic infection only. Universal screening of all admissions may help to identify these patients early and enable appropriate isolation and monitoring.

Haematology patients frequently have a potentially curable malignancy and/or temporary therapy‐induced immune impairment and should, therefore, be considered for higher‐level supportive interventions such as NIV or IMV, despite having therapy‐induced cytopenias and immune impairment. Treatment escalation plans should be made by clinicians with expert knowledge of the underlying haematological diagnosis, in consultation with critical‐care colleagues. Furthermore, as many haematology patients will not be able to access novel therapies through clinical trials due to threshold laboratory values or recent use of other biologic agents, other routes to access promising therapeutic agents for COVID‐19 need to be considered.

Recent data from patients in the general population with COVID‐19 have identified that haematological parameters including anaemia or thrombocytopenia are risk factors for severe disease. 1 , 26 In haematology patients these parameters are confounded by underlying disease: accordingly, no significant association between haematological parameters and risk of severe disease/mortality was identified in this cohort, further highlighting the importance of determining other risk factors to assess disease severity in this patient group.

Coagulopathy in COVID‐19 pathophysiology is an ongoing area of research, with early observations highlighting high rates of VTE occurrence, particularly in those with severe COVID‐19. 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 Prophylactic LMWH, unless contraindicated, is, therefore, advised for all COVID‐19 patients. 31 Patients with haematological malignancies present further challenges due to additional VTE risk from underlying malignancy, repeated prolonged hospital admissions and indwelling central venous catheter use, as well as cytopenias from underlying disease or SACT. In this study, VTE rates of 13% despite prophylactic LMWH use were seen, highlighting the low index of clinical suspicion for VTE required in this setting. Further studies with prolonged follow‐up are required to determine which patients may benefit from empirical intermediate/treatment dose anticoagulation, or extended prophylaxis post discharge. Combining anticoagulation with SACT therapy remains challenging in this patient cohort and requires robust planning to reduce both VTE and bleeding risks. However, all patients should be VTE risk‐assessed for at least thromboprophylaxis, and higher doses of anticoagulation may be appropriate dependant on additional risk factors.

Gaining insight into the duration of viral shedding in this patient population is paramount in estimating transmission risk. Compared to reports from Chinese patient cohorts, where median duration of shedding was 20 days, our cohort of haematology patients demonstrated prolonged viral shedding. 1 , 26 However, implications of viral shedding on infection rates are unknown as viral culture studies were not performed.

Although this study reveals valuable early insights into the management of this patient group within the evolving pandemic, limitations remain, particularly in cohort size and underlying disease heterogeneity. The valuable early insights gained in such case series with detailed case annotation must be complemented by validation within a larger dataset where multivariable analysis is possible. An international collaborative effort is required in order to further understand COVID‐19 infection in specific disease groups.

In conclusion, we describe risk factors and outcomes for 55 haematology patients, including the largest series of haematology patients on current SACT to date. The SARS‐CoV‐2 pandemic presents an unprecedented challenge to haematologists and their patients who are on SACT. While our data confirm that haematology patients represent a high‐risk cohort, the majority of patients survive, even in the context of recent SACT. Risk factors for disease severity and mortality within this group have been identified which may assist with risk stratification and decisions regarding hospital admission but require validation in larger datasets. Finally, our data indicate that chemo‐immunotherapy can be safely delivered to these patients but may require regimen modification, and effects on long‐term disease control remain to be clarified.

Author contributions

TAF and KMA wrote the project proposal, IRAS form and obtained HRA approval. TAF, ETB, WYC, JD, SJC, EAK, KD and OT collected the data. AAK analysed the data, and created the figures. All authors were involved in the writing of the manuscript and provided clinical care for the patients described. All authors had access to the clinical and laboratory data. TAF and KMA had final responsibility to submit for publication.

Supporting information

Table SI. WCC, white cell count; ref, reference range; CRP, C‐reactive protein; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; ALT, alanine transaminase. All percentages rounded to the nearest whole number. * denotes a significant result (P < 0.05).

Table SII. Intensive and non‐intensive SACT regimes.

Table SIII. Microbiology and virology co‐infection data.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge all the medical, nursing and allied health professionals who provided clinical care for this cohort of patients during this difficult time. We would like to acknowledge Jiexin Zheng, Mike Northend, Catherine Zhu, Lorna Neill, Kushani Ediriwickrema, Rosie Amerikanou, Sneha Patel, Jin‐Sup Shin, Pemantah Ramdeny, Edward Poynton and Moosa Qureshi for their assistance with the data collection.

References

- 1. Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, Fan G, Liu Y, Liu Z, et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID‐19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395:1054–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Docherty AB, Harrison EM, Green CA, et al. Features of 16,749 hospitalised UK patients with COVID‐19 using the ISARIC WHO Clinical Characterisation Protocol. medRxiv. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3. Dai M, Liu D, Liu M, Zhou F, Li G, Chen Z, et al. Patients with cancer appear more vulnerable to SARS‐COV‐2: a multi‐center study during the COVID‐19 outbreak. Cancer Discov. 2020;CD‐20‐0422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Liang W, Guan W, Chen R, Wang W, Li J, Xu K, et al. Cancer patients in SARS‐CoV‐2 infection: a nationwide analysis in China. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:335–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wang H, Zhang L. Risk of COVID‐19 for patients with cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:e181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72314 cases from the Chinese center for disease control and prevention. JAMA. 2020;323:1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zhang L, Zhu F, Xie L, Wang C, Wang J, Chen R, et al. Clinical characteristics of COVID‐19‐infected cancer patients: a retrospective case study in three hospitals within Wuhan, China. Annals of Oncol. 2020;31:894–901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. El‐Sharkawi D, Iyengar S. Haematological cancers and the risk of severe COVID‐19: Exploration and critical evaluation of the evidence to date. Br J Haematol. 2020; 10.1111/bjh.16956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gosain R, Abdou Y, Singh A, Rana N, Puzanov I, Ernstoff MS. COVID‐19 and cancer: a comprehensive review. Curr Oncol Rep. 2020;22:53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kanellopoulos A, Ahmed MZ, Kishore B, Lovell R, Horgan C, Paneesha S, et al. COVID‐19 in bone marrow transplant recipients: reflecting on a single centre experience. Br J Haematol. 2020;190. 10.1111/bjh.16856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. He W, Chen L, Chen L, Yuan G, Fang Y, Chen W, et al. COVID‐19 in persons with haematological cancers. Leukemia. 2020;34:1637–45. 10.1038/s41375-020-0836-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Martín‐Moro F, Marquet J, Piris M, Michael BM, Sáez AJ, Corona M, et al. Survival study of hospitalised patients with concurrent COVID‐19 and haematological malignancies. Br J Haematol. 2020;190: 10.1111/bjh.16801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Aries JA, Davies JK, Auer RL, Hallam SL, Montoto S, Smith M, et al. Clinical outcome of coronavirus disease 2019 in haemato‐oncology patients. Br J Haematol. 2020;190. 10.1111/bjh.16852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Booth S, Willan J, Wong H, Khan D, Farnell R, Hunter A, et al. Regional outcomes of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection in hospitalised patients with haematological malignancy. Eur J Haematol. 2020. 10.1111/ejh.13469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Shah V, Ko Ko T, Zuckerman M, Vidler J, Sharif S, Mehra V, et al. Poor outcome and prolonged persistence of SARS‐CoV‐2 RNA in COVID‐19 patients with haematological malignancies; King's College Hospital experience. Br J Haematol. 2020. 10.1111/bjh.16935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence . COVID‐19 rapid guideline: delivery of systemic anticancer treatments. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng161/resources/covid19-rapid-guideline-delivery-of-systemic-anticancer-treatments-pdf-66141895710661. Accessed 16 May 2020. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Andrew JW, Ethan T‐B, Maryam S, Fiona C, Rajeev G, Adele K, et al. Fielding Successful remission induction therapy with gilteritinib in a patient with de novo FLT3‐mutated acute myeloid leukaemia and severe COVID‐19. Br J Haematol. 2020. 10.1111/bjh.16962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. DiNardo CD, Pratz K, Pullarkat V, Jonas BA, Arellano M, Becker PS, et al. Venetoclax combined with decitabine or azacitidine in treatment‐naive, elderly patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2019;133:7–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Perl AE, Martinelli G, Cortes JE, Neubauer A, Berman E, Paolini S, et al. Gilteritinib or chemotherapy for relapsed or refractory FLT3‐mutated AML. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:1728–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Fielding A. A study for older adults with acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (UKALL60+). https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01616238. Accessed 16 May 2020.

- 21. Intensive Care National Audit & Research Centre . ICNARC report on COVID‐19 in critical care. 15 May 2020. https://www.icnarc.org/Our-Audit/Audits/Cmp/Reports. Accessed 16 May 2020.

- 22. National Cancer Research Institute . Recommendations for the management of patients with AML during the COVID19 outbreak: a statement from the NCRI AML Working Party. http://www.cureleukaemia.co.uk/media/upload/files/aml-covid-v3.4.pdf. Accessed 16 May 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kuderer NM, Choueiri TK, Shah DP, Shyr Y, Rubinstein SM, Rivera DR, et al., Covid & Cancer, C . Clinical impact of COVID‐19 on patients with cancer (CCC19): a cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395:1907–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lee LYW, Cazier JB, Starkey T, Turnbull CD, Team UKCCMP, Kerr R, et al. COVID‐19 mortality in patients with cancer on chemotherapy or other anticancer treatments: a prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395:1919–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Brissot E, Labopin M, Baron F, Bazarbachi A, Bug G, Ciceri F, et al. Management of patients with acute leukemia during the COVID‐19 outbreak: practical guidelines from the acute leukemia working party of the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2020. 10.1038/s41409-020-0970-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Cui S, Chen S, Li X, Liu S, Wang F. Prevalence of venous thromboembolism in patients with severe novel coronavirus pneumonia. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18:1421–4. 10.1111/jth.14830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Helms J, Tacquard C, Severac F, Leonard‐Lorant I, Ohana M, Delabranche X, et al. & Group, C.T . High risk of thrombosis in patients with severe SARS‐CoV‐2 infection: a multicenter prospective cohort study. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46:1089–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Klok FA, Kruip MJHA, van der Meer NJM, Arbous MS, Gommers DAMPJ, Kant KM, et al. Incidence of thrombotic complications in critically ill ICU patients with COVID‐19. Thromb Res. 2020;191:145–7. 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Middeldorp S, Coppens M, Haaps TF, Foppen M, Vlaar AP, Müller MCA, et al. Incidence of venous thromboembolism in hospitalized patients with COVID‐19. J Thromb Haemost. 2020. 10.1111/jth.14888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Thachil J, Tang N, Gando S, Falanga A, Cattaneo M, Levi M, et al. ISTH interim guidance on recognition and management of coagulopathy in COVID‐19. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18:1023–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table SI. WCC, white cell count; ref, reference range; CRP, C‐reactive protein; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; ALT, alanine transaminase. All percentages rounded to the nearest whole number. * denotes a significant result (P < 0.05).

Table SII. Intensive and non‐intensive SACT regimes.

Table SIII. Microbiology and virology co‐infection data.