Abstract

Background

Because of the global spread of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19), oncology departments across the world have rapidly adapted their cancer care protocols to balance the risk of delaying cancer treatments and the risk of COVID‐19 exposure. COVID‐19 and associated changes may have an impact on the psychosocial functioning of patients with cancer and survivors. This study was designed to determine the impact of the COVID‐19 pandemic on young people living with and beyond cancer.

Methods

In this cross‐sectional study, 177 individuals, aged 18 to 39 years, were surveyed about the impact of COVID‐19 on their cancer care and psychological well‐being. Participants also reported their information needs with respect to COVID‐19. Responses were summarized with a content analysis approach.

Results

This was the first study to examine the psychological functioning of young patients and survivors during the first weeks of the COVID‐19 pandemic. A third of the respondents reported increased levels of psychological distress, and as many as 60% reported feeling more anxious than they did before COVID‐19. More than half also wanted more information tailored to them as young patients with cancer.

Conclusions

The COVID‐19 pandemic is rapidly evolving and changing the landscape of cancer care. Young people living with cancer are a unique population and might be more vulnerable during this time in comparison with their healthy peers. There is a need to screen for psychological distress and attend to young people whose cancer care has been delayed. As the lockdown begins to ease, the guidelines about cancer care should be updated according to this population's needs.

Keywords: adolescent cancer, anxiety, coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19), depression, information needs, survey, young adult cancer

Short abstract

This study examines the psychological functioning of young people living with and beyond cancer during the first weeks of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) pandemic. A third have reported increased levels of psychological distress, and as many as 60% have reported feeling more anxious than they did before COVID‐19.

Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) was first identified in China in December 2019 1 and is an infectious disease caused by the novel virus called severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV‐2). 2 In most patients, COVID‐19 infection results in mild symptoms such as a fever and a dry cough, but in some cases and particularly in those with underlying health conditions and those who are immunocompromised, COVID‐19 can be more severe and can result in serious complications such as acute respiratory distress syndrome or even death. 3 To date, findings suggest that COVID‐19 poses little threat to children and young people 4 ; however, patients with cancer and survivors may be a vulnerable population. Individuals undergoing active treatment or taking immunosuppressive medication are known to be at higher risk for viral infections, 5 whereas those in survivorship might experience distress because of changes in their follow‐up care. Most young people living beyond cancer worry about cancer recurrence 6 , 7 and resultantly the disrupted follow‐up care, which includes physical examinations, and screening may lead to heightened anxiety. As such, adolescent and young adult (AYA) patients with cancer and survivors remain a group with unique needs during a pandemic outbreak such as the current COVID‐19 outbreak, even though the relative risks of infection and mortality for this population have not yet been established.

AYA patients with cancer and survivors have been recognized as a unique group of patients who face different challenges and needs than their younger peers or older adults. 8 , 9 In response to the global spread of the novel SARS‐CoV‐2, oncology departments quickly acted and adapted measures and protocols for cancer care. Most centers sought to balance the risk of delaying cancer treatment with that of exposing a vulnerable patient with cancer to the virus, and this resulted in crucial reprioritization; the most essential and necessary treatments remained on schedule, whereas early preventative screenings, follow‐up appointments, and nonessential surgeries were often delayed. 10 These changes were made rapidly, and the newly devised guidelines were operationalized with increased survival in mind and in hopes of rendering the oncology centers pandemic‐proof. 11 , 12 Although taking such measures is necessary for successful infection control, the subsequent steps will have to involve consideration of the psychological impact of COVID‐19 and related changes on patients with cancer, survivors, and their families.

Even though the scientific and patient support communities were quick to recognize the need to provide information about COVID‐19 to patients with cancer, 13 the sudden increase in and plethora of resources available were not necessarily tailored to AYA patients' and survivors' needs. We do not know whether the information available is adequate or whether AYAs living with or beyond cancer feel confident about making sense of and applying this information.

As after any major global disaster, the COVID‐19 pandemic is also likely to result in increased mental health symptomatology. 14 , 15 Because a subset of AYA patients with cancer experience significant levels of psychological distress even under normal circumstances, 16 , 17 it is important to recognize that worries associated with the pandemic and any delays in lifesaving treatments are likely to contribute to the anxiety in this population. Furthermore, the social distancing measures imposed to contain the spread of the infection may have unintended consequences for mental health via changes in social support, economic consequences, and changes to daily routines. 18 In AYAs who are already vulnerable to experiencing distress, this may further compound anxiety. To ensure that the needs of AYAs continue to be met during and after the COVID‐19 outbreak, developing new strategies that will help to manage and attenuate worries about COVID‐19 exposure should be a priority. This effectively requires an understanding of what the needs of AYAs are in this unprecedented context.

To adapt and better prepare for any future outbreaks, it is important to understand the impact of the novel SARS‐CoV‐2 on AYAs' cancer care and their well‐being. The aims of this study were 1) to gather initial evidence of the impact of COVID‐19 on AYA cancer patients' and survivors' psychological well‐being and cancer care and 2) to understand where they received the information about the pandemic and how satisfied they were with the resources on COVID‐19.

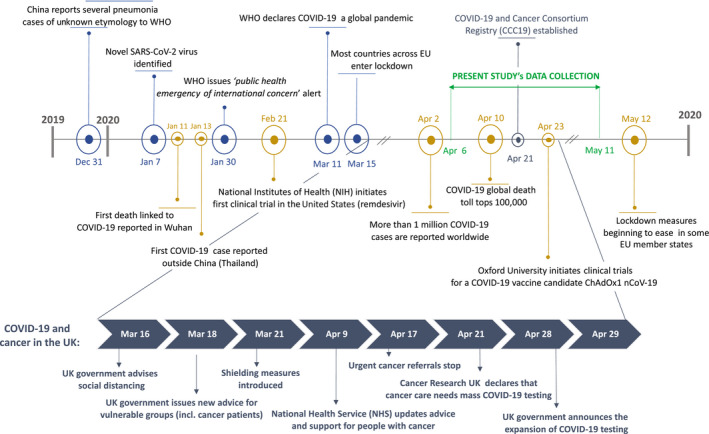

To provide the future readership with context, Figure 1 provides an overview with all the relevant dates and facts known to the authors at the time of writing this article (May 12, 2020).

Figure 1.

Global and UK COVID‐19 context at the time of this study. This figure is aimed at providing future readership with the COVID‐19 context at the time of this writing (May 12, 2020). By mid‐March, most countries across Europe had begun nationwide lockdowns. At the beginning of April, most cancer centers began adapting their treatment protocols. By late April, CCC19 had been established, with currently more than 100 participating institutions globally reporting results about COVID‐19 outcomes in patients with cancer. There are currently several vaccine trials that have already begun testing in healthy human participants. CCC19 indicates COVID‐19 and Cancer Consortium Registry; COVID‐19, coronavirus disease 2019; EU, European Union; SARS‐CoV‐2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; WHO, World Health Organization.

Materials and Methods

This anonymous, cross‐sectional survey was an extension of an ongoing longitudinal study exploring the predictors of psychological well‐being and holistic recovery in AYA patients with cancer. The original study protocol and the COVID‐19 survey material can be viewed at https://osf.io/ncpv8/. This study was approved by the Medical Sciences Inter‐Divisional Research Ethics Committee at the University of Oxford (R61437/RE005).

Data were collected via Qualtrics, secure online survey software, via an anonymous link distributed on social media outlets and online via patient organizations' web posts or newsletters. Participants were provided brief information about the study and eligibility criteria as well as its current aim: understanding the impact of COVID‐19 on their cancer care and well‐being. The survey had 2 equal arms, a Slovenian arm and an English arm, accessible to anyone who was able to read and respond in English. Participants were all patients with cancer or survivors aged 18 to 39 years who had been diagnosed with any form of malignant cancer when they were 10 years old or older.

Measures and Survey Description

Demographic and medical information

Participants reported their age, sex, geographical region, and current living arrangement. They also reported their current health status, treatment status, whether or not they had a preexisting mental health condition or other chronic illness, and whether they were taking any immunosuppressant medication (ie, steroids).

Psychological distress

Psychological distress was measured with the Patient Health Questionnaire for Depression and Anxiety (PHQ‐4), a 4‐item measure of the frequency of 2 anxiety symptoms and 2 depressive symptoms on a 4‐point Likert scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day). The reliability and validity of the brief PHQ‐4 scale have been established in general and clinical populations, and a score of 3 or higher on either subscale and a total score of 6 or higher are indicative of clinically relevant distress. 19 , 20 Cronbach's α in our study was 0.84 for the PHQ‐4 and 0.83 and 0.78 for the anxiety and depression subscales, respectively.

COVID‐19: impact on care and information resources

Respondents self‐reported if and how the pandemic‐related events disrupted their cancer treatment and care, what the impact of the pandemic was on their psychological well‐being, where they received the information about the novel SARS‐CoV‐2, and how satisfied they were with the information available on a scale from 0 (least satisfied/trustworthy) to 10 (most satisfied/trustworthy; see https://osf.io/ncpv8/).

Analysis

The analyses were conducted in R (version 3.6.3) 21 with the following packages: ggplot2 (version 3.3.0), 22 dplyr (version 0.8.5), 23 psych (version 1.9.12.31), 24 and papaja (version 0.1.0.984). 25

Survey data were analyzed in an exploratory and descriptive manner to provide preliminary evidence of the impact of the COVID‐19 pandemic on the subjective well‐being of patients with cancer. We also reported the self‐reported impact of COVID‐19 on individuals' cancer treatment protocols.

Qualitative responses were analyzed via a content analysis approach. 26 The approach has been described as suitable for mixed method research and allows for a more positivistic approach to analysis and the description of phenomena. 27 Two researchers (U.K. and S.R.) independently read and coded all of the responses to open‐ended questions about the impact of COVID‐19 on the psychological well‐being of patients with cancer and their caretakers. The researchers coded responses both deductively by organizing them around the current study aims and survey questions and inductively by devising a list of categories to describe the impact on cancer care and the most common worries from participants' descriptions. The formulated categories were refined and operationalized into a coherent list, upon which all qualitative responses were mapped. The interrater reliability for this procedure was 96%. Lastly, the classification of responses was checked by a third author, and discrepancies were resolved in a consensus meeting. All illustrative quotes in the main body are from different participants.

Results

Participants

During the period between April 6 and May 12, 2020, 177 AYA patients with cancer and survivors participated in the study and completed at least 80% of the survey. Thirty‐nine were from the Slovenian arm, and 138 were from the English arm. Participants' demographic and medical information is presented in Table 1. On average, patients with cancer were 29.33 years old (SD, 6.17 years). A third of the responders (57 of 177) were in active treatment at the time of the study, 14% (24 of 177) had completed treatment within the previous 6 months, and 54% (96 of 177) had completed their cancer treatment more than 6 months ago. In the last group, 14 individuals (15%) were still taking immunosuppressive medication.

Table 1.

Demographic and Medical Information of the Participants (n = 177)

| Variable | Value |

|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) [range], y | 29.33 (6.17) [18‐39] |

| Sex, No. (%) | |

| Female | 154 (87) |

| Male | 20 (11) |

| Prefer not to answer | 3 (2) |

| Region, No. (%) | |

| North America | 92 (53) |

| Central and South America | 2 (1) |

| Europe | 78 (44) |

| Middle East | 1 (1) |

| Africa | 0 (0) |

| Asia | 1 (1) |

| Oceania | 3 (2) |

| Living arrangement, No. (%) | |

| Alone | 24 (14) |

| Shared house | 13 (7) |

| Partner only | 45 (25) |

| Parents | 20 (11) |

| Family | 72 (41) |

| Other | 4 (2) |

| Treatment status, No. (%) | |

| Undergoing treatment | 57 (32) |

| Completed within 6 mo | 24 (14) |

| Completed more than 6 mo ago | 96 (54) |

| Immunosuppressant medications, No. (%) | |

| Yes | 41 (23) |

| No | 122 (69) |

| Prefer not to answer | 14 (8) |

| Mental health diagnosis, No. (%) | |

| Yes | 66 (37) |

| No | 108 (61) |

| Prefer not to answer | 3 (2) |

COVID‐19 Impact on Cancer Care

Forty‐five percent of AYA patients with cancer (79 of 177) reported that COVID‐19 had an impact on their cancer treatment or care, and 21% (38 of 177) reported no impact at the time but worried that there might be.

According to the short answers, the analyses revealed 6 categories of most commonly reported changes in cancer care. These categories were as follows: follow‐up appointments being postponed or cancelled, appointments being performed over the phone or virtually, cancer treatment and/or surgery being postponed, having to be alone during the treatment, having reduced access to medicine, and experiencing changes in treatment protocols (eg, reduced bloodwork or oral chemotherapy instead of intravenous chemotherapy).

COVID‐19 Impact on Psychological Well‐Being

More than a third of AYA participant scored in the clinical range for psychological distress. Individuals who were undergoing treatment or were within 6 months of treatment completion reported higher levels of psychological distress on average. Symptoms of anxiety were more common than depressive symptomatology. The mean scores and proportions of participants scoring in the clinical range of psychological distress are reported in Table 2.

Table 2.

Psychological Distress Among Adolescents and Young Adults

| No. | Mean (SD) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anxiety | Depression | Total | ||

| Total sample | 177 | 2.61 (1.94) | 1.92 (1.71) | 4.53 (3.29) |

| Undergoing treatment | 57 | 2.84 (1.89) | 2.07 (1.69) | 4.91 (3.22) |

| Completed within 6 mo | 24 | 3.54 (2.02) | 2.29 (1.90) | 5.83 (3.60) |

| Completed more than 6 mo ago | 96 | 2.24 (1.87) | 1.73 (1.66) | 3.97 (3.15) |

| No. | No. (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anxiety | Depression | Total | ||

| Total sample | 177 | 56 (32) | 34 (19) | 51 (29) |

| Undergoing treatment | 57 | 20 (35) | 10 (18) | 17 (30) |

| Completed within 6 mo | 24 | 12 (50) | 6 (25) | 12 (50) |

| Completed more than 6 mo ago | 96 | 24 (25) | 18 (19) | 22 (23) |

The Patient Health Questionnaire for Depression and Anxiety items are rated on a 4‐point Likert scale ranging from 0 to 3. The upper half of the table lists means and SDs, whereas the bottom half lists numbers and proportions of individuals scoring in the clinical range.

In addition, participants were asked how they felt in comparison with before the pandemic. Sixty‐two percent of the respondents (109 of 177) reported feeling more anxious than before, 29% (52 of 177) reported feeling the same, and 9% (16 of 177) reported feeling less anxious than before. The proportion of individuals feeling more anxious was the same for those currently in treatment and those who had completed treatment more than 6 months ago (see the Supporting Table 1).

The short responses revealed that the most common concerns among AYAs related to COVID‐19 and their health status were as follows: not being sure how big of a risk COVID‐19 posed for them or how their body would react to the infection, being anxious about experiencing serious complications if they were to catch the virus, and having their cancer care delayed. However, individuals also reported an impact on mood as well as worries about their family members, returning to “the normal,” and finances. The categories of participants' responses and examples can be viewed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Categories of Content on the Impact of COVID‐19 on Psychological Well‐Being

| Category | Definition | Example |

|---|---|---|

| General anxiety | Broad statements and descriptions of anxiety and worries that are not specified or described in detail | “My anxiety levels tend to be quite high. I had felt like I had my anxiety under control, but this situation has thrown me off.” |

| Health anxiety | Broad statements of worries about own health and hypochondria, including concerns about individuals' mental health and illness triggers | “I worry that my current health problems will not be taken as seriously in the healthcare system as they were before.” |

| Loneliness | Mentions of lacking support, feeling low and sad because of isolation, feelings of loneliness | “Whereas I was isolated prior to the global lockdown, I was still able to have the physical support of my family given that they were healthy. I have now lost that, making navigating cancer treatment all the more lonely.” |

| Low mood | Broader descriptions of low mood or morale, depression | “Increased feelings of depression and overeating.” |

| Disruptions | Refers to the impact on mental health and well‐being due to disruptions in daily living and activities | “My biggest source of happiness was my job and not being able to see my students is heartbreaking.” |

| Death/dying | Explicit mentions about dying and mortality | “I am constantly worried that if I fall sick, I will end up dying considering my cancer history and weak immune system.” |

| Worry about COVID‐19: self | Worries about how one's body would react to COVID‐19, worries about severe complications due to COVID‐19, including worries about receiving adequate care if one were to contract COVID‐19 | “I am worried that if I caught it, I would be one of the ones that do not do well as I have had radiation to my spleen and still have low lymphocytes.” |

| Worry about COVID‐19: others | Worries about close individuals or family members contracting the virus | “Mostly worried about family/elder members of the family wanting to get outside more.” |

| Cancer care | Changes and disruptions in cancer care, which are unfavorable; worry about continuing with care and going to the hospital, where many people are infected | “I worry about what stage my cancer will be when they are finally able to do my surgery/treatment.” |

| Return to normal | Concerns about how to return to normal, what normal will look like; worries about returning back to work | “Going back to work eventually stresses me.” |

| Finance | Direct financial impact from job loss or disruption; loss of insurance | “I have lost my job, risk losing my insurance, and will be in active treatment until late summer.” |

Abbreviation: COVID‐19, coronavirus disease 2019.

Moreover, physical distancing measures imposed by many authorities resulted in social isolation, with 52% of AYAs (90 of 173) reporting feeling more isolated than they did before the pandemic. On the other hand, 39% (68 of 173) reported feeling about the same, and 9% (15 of 173) reported feeling less isolated than before and better understood by their friends and family:

Even though I am still as isolated as I was when going through treatment and recovery, I find I feel less isolated than before because now my friends and family understand a lot better how it feels.

The qualitative responses highlighted that despite an increase in social interactions online, many individuals missed a more intimate human connection with others. Although a few individuals reported having more time for themselves and their families, others reported that the isolation made them more anxious, depressed, and claustrophobic. Their needs as patients with cancer were felt to have become secondary:

People are so concerned with COVID‐19 that they don't care about my cancer anymore.

For some, isolation also acted as a trigger and reminded them of their cancer:

It makes me feel like I am in the first steps of my treatment all over again.

COVID‐19 Information Resources and Satisfaction

Participants were asked what sources they relied on for obtaining information related to the COVID‐19 pandemic. The majority of respondents (159 of 172) relied on a minimum of 2 different sources, with the general news being most read (135 of 172); this was followed by social media (109 of 172). Less than a third (46 of 172) relied on cancer support groups and patient organizations for COVID‐19–specific information. Individuals in different illness phases reported relying on the same information resources. Satisfaction with the available information related to COVID‐19 and its trustworthiness were perceived to be moderate (6.2/10 and 6.1/10, respectively), with individuals currently undergoing treatment reporting the least satisfaction and trustworthiness for the available information (see the Supporting Table 4 for a breakdown by treatment status).

Only 24% of the respondents (42 of 173) reported receiving direct communication regarding COVID‐19 from their oncologists or health care teams, with the majority of these respondents (64%) undergoing treatment at the time of this study. More than half of the participants (56% [96 of 170]) reported wanting more information about how to cope with the pandemic (see the Supporting Tables 2 and 3 for a breakdown by treatment status). Furthermore, 35% of AYAs (60 of 172) would have preferred information about COVID‐19 tailored to their needs as young patients with cancer and survivors:

It would be nice to have something to read designed with me in mind.

On the other hand, a few individuals reported that having more information would be overwhelming, and some reported the need for information specifically for mental health resources for patients with cancer during a pandemic.

Discussion

Evidence to date suggests that young people are at lower risk for contracting the novel SARS‐CoV‐2 virus or developing serious complications from it 4 , 28 ; however, youth living with and beyond cancer might be at increased risk because of the compromised immunity resulting from illness and/or late effects of cancer. 5 , 29 Moreover, changes in cancer care protocols may increase the levels of anxiety and uncertainty not only for those undergoing active treatment but also for individuals in long‐term care. Our cross‐sectional study of youth living with and beyond cancer, conducted in the initial weeks of the COVID‐19 pandemic, found that 3 in 10 AYAs experienced increased levels of psychological distress, with anxiety being more prominent than depressive symptomatology. As many as 6 in 10 AYAs reported feeling more anxious during the COVID‐19 pandemic than they had previously.

Higher levels of distress during a pandemic outbreak might be expected, 14 and a variety of psychological problems such as panic disorder, anxiety, and depression due to the COVID‐19 pandemic have already been observed in the general population. 30 It may be that this is compounded for patients with cancer because of the salience of risks to their health and their vulnerability due to immunosuppression. The themes driving anxiety and worry for our participants were predominantly related to physical health and cancer‐related concerns. A recent study of Italian adolescent patients with cancer and survivors revealed that both groups worried about contracting the virus and felt personally at risk for severe complications, with survivors reporting more worry than those in follow‐up care. 31 When stratified by treatment status, our results revealed the highest levels of anxiety in those who had completed treatment within the past 6 months, who were followed by those in treatment at the time of the study. We speculate that this may in part be due to the uncertainty often experienced upon treatment completion, when individuals often have to wait for scans before remission can be confirmed. These treatment transitions can be burdensome for patients. 9 , 32 The first few months after treatment are also often marked by frequent follow‐up appointments, all of which were likely postponed or cancelled because of the current pandemic. The added uncertainty is likely to contribute to anxiety symptoms.

The lowest levels of clinically elevated psychological distress were present in those off treatment, for whom the care was also least affected by the pandemic and associated events. Nevertheless, a high proportion of those off treatment also reported feeling more anxious now than they did before the pandemic.

The social impact of the disease containment measures has been considerable. Most governments and authorities across the world have imposed physical distancing as a way to slow the spread of the virus within communities. For many, these measures resulted in social isolation, which can result in increased feelings of loneliness and further contribute to the feelings of low mood and anxiety. 33 The majority of our participants recounted being familiar with isolation measures because of their cancer experience. For some AYAs, de novo isolation acted as a negative reminder of their illness, whereas almost 10% reported feeling less anxious and isolated in comparison with the time before the pandemic. The qualitative responses revealed that this may be due to the fact that they felt better understood, spent more time with their families, or even found more time for themselves.

Research to date suggests that AYAs with cancer like to be involved in their care and need tailored, age‐appropriate information about their cancer, care, late effects, and resources. 34 , 35 Only a quarter of our participants reported receiving direct communication related to COVID‐19 from their health care providers, and we demonstrated that more than half of the AYAs would have liked to have received more information on how to cope during the COVID‐19 pandemic and specifically information tailored to them as young patients with cancer and survivors. Regardless of the time that had passed since diagnosis, the most common worry was knowing the extent of the risk for contracting the virus and how their body would react if they were to contract the infection.

Unlike Italian adolescents, 31 our AYA participants consumed most of the news related to the pandemic via general news sources, which were followed by social media outlets. This difference may be due to the older age of our sample. The fact that AYAs received most information from general news sources could also explain the reported need for more tailored information. The utility of social media as a way of delivering reliable information as well as interventions to AYA cancer communities is gaining traction and could pave the way for an eHealth approach to oncological AYA care. 36 Preliminary evidence supports the feasibility and acceptability of online psychosocial interventions for AYAs in treatment 37 or early posttreatment phases 38 ; however, future research should carefully evaluate if online support and digital approaches to care respond equally well to the needs of AYAs living with and beyond cancer.

Strengths and Limitations

Although the global reach and early data collection add the largest contribution to the growing body of knowledge about the COVID‐19 pandemic, there are several limitations that limit the generalizability of our work. Our sample size was relatively small, highly heterogeneous, and mostly female, and most responses were submitted from North America and Europe. Although a geographically diverse sample offers broad and preliminary insights into COVID‐19–related concerns of AYAs globally, it also limits generalizability because of the diverse health care systems, time lags between peaks of the pandemic across different countries, and measures taken to prevent the spread of COVID‐19.

Participants were a self‐selected group who responded to the online study post, and we collected only minor though relevant details related to their medical and cancer history. Moreover, the survey was cross‐sectional in nature, with psychological distress assessed with a very brief measure, and it relied on short answer questions, to which many individuals provided responses with limited context and detail. We relied on retrospective self‐reporting of changes in psychological distress since the advent of COVID‐19, which is subject to reporting biases. Nevertheless, we have provided important preliminary evidence that offers invaluable directions for future research on the impact of COVID‐19, and we have also captured the experiences of this vulnerable population in the early weeks of the COVID‐19 pandemic. Our sample included respondents at different stages of cancer treatment and beyond.

Clinical Implications

The COVID‐19 pandemic is rapidly evolving, and we learn new details every day. Even though the disruptions in our daily routines and health care systems pose many challenges, therein lie many opportunities for improvement of AYA cancer care in the future. The current situation highlights the continued need to screen for psychological distress and attend to those who might be experiencing distress even under normal circumstances. Finding ways of doing this while providing follow‐up care remotely is particularly important within the current ways of working, and the brief PHQ‐4 used in this study may offer a promising way to monitor psychological distress in clinical contexts.

The health care teams should actively engage and provide relevant and reliable information about COVID‐19 for patients with cancer and survivors as well as information about any mental health resources. This will be important as the lockdown measures begin to ease in the coming months. Individuals whose care was delayed should receive adequate support so that they follow through with their appointments and continue the necessary treatment. Although attending to those who are undergoing treatment or have just recently completed it has been a priority, our results emphasize that the needs of long‐term survivors should not be overlooked because many may be experiencing higher levels of distress on account of their illness history.

Telemedicine and eHealth might offer a favorable approach for some AYAs; however, in scaling them up, we have to ensure that we do not leave behind those with limited access to digital technologies.

Funding Support

Urška Košir acknowledges the support of the Economic and Social Research Council and Ad Futura (Slovenia) as well as the following patient organizations for help with recruitment and continued support of research endeavors: Europa Donna Slovenia, Lymphoma and Leukemia Society, OnkoMan, OnkoNet, and Elephants and Tea. Maria Loades is funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) through a doctoral research fellowship (DRF‐2016‐09‐021). Jennifer Wild's research is supported by MQ and the NIHR Oxford Health Biomedical Research Centre. This report is independent research. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the National Health Service, NIHR, or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures

The authors made no disclosures.

Author Contributions

Urška Košir: Conceptualization, data analysis and interpretation, and writing–original draft. Maria Loades: Data analysis and interpretation and writing–original draft. Jennifer Wild: Data interpretation and writing–review and editing. Milan Wiedemann: Data analysis and interpretation and writing–review and editing. Alen Krajnc: Data collection, data interpretation, and writing–review and editing. Sanja Roškar: Data analysis and interpretation. Lucy Bowes: Study design and conceptualization, data analysis and interpretation, and writing–review and editing.

Supporting information

Table S1‐S4

Košir U, Loades M, Wild J, Wiedemann M, Krajnc A, Roškar S, Bowes L. The impact of COVID‐19 on the cancer care of adolescents and young adults and their well‐being: Results from an online survey conducted in the early stages of the pandemic. Cancer. 2020:126:4414–4422. 10.1002/cncr.33098

We thank all participants who took the time to respond during these stressful times.

References

- 1. Lu H, Stratton CW, Tang YW. Outbreak of pneumonia of unknown etiology in Wuhan, China: the mystery and the miracle. J Med Virol. 2020;92:401‐402. doi:10.1002/jmv.25678 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. World Health Organization . Clinical Management of Severe Acute Respiratory Infection When Novel Coronavirus (nCoV) Infection Is Suspected: Interim Guidance. Accessed May 12, 2020. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/331446?search‐result=true&query=10665%2F331446&scope=&rpp=10&sort_by=score&order=desc

- 3. Rothan HA, Byrareddy SN. The epidemiology and pathogenesis of coronavirus disease (COVID‐19) outbreak. J Autoimmun. 2020;109:102433. doi:10.1016/j.jaut.2020.102433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chen N, Zhou M, Dong X, et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet. 2020;395:507‐513. doi:10.1016/S0140‐6736(20)30211‐7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kamboj M, Sepkowitz KA. Nosocomial infections in patients with cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:589‐597. doi:10.1016/S1470‐2045(09)70069‐5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Koch L, Jansen L, Brenner H, Arndt V. Fear of recurrence and disease progression in long‐term (≥5 years) cancer survivors—a systematic review of quantitative studies. Psychooncology. 2013;22:1‐11. doi:10.1002/pon.3022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kosir U, Wiedemann M, Wild J, Bowes L. Cognitive mechanisms in adolescent and young adult cancer patients and survivors: feasibility and preliminary insights from the Cognitions and Affect in Cancer Resiliency Study. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol. 2020;9:289‐294. doi:10.1089/jayao.2019.0127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Marjerrison S, Barr RD. Unmet survivorship care needs of adolescent and young adult cancer survivors. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1:e180350. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.0350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Barr RD, Ferrari A, Ries L, Whelan J, Bleyer WA. Cancer in adolescents and young adults: a narrative review of the current status and a view of the future. JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170:495‐501. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.4689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dinmohamed AG, Visser O, Verhoeven RHA, et al. Fewer cancer diagnoses during the COVID‐19 epidemic in the Netherlands. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:750‐751. doi:10.1016/S1470‐2045(20)30265‐5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. van de Haar J, Hoes LR, Coles CE, et al. Caring for patients with cancer in the COVID‐19 era. Nat Med. 2020;26:665‐671. doi:10.1038/s41591‐020‐0874‐8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Schrag D, Hershman DL, Basch E. Oncology practice during the COVID‐19 pandemic. JAMA. Published online April 13, 2020. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.6236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Nekhlyudov L, Duijts S, Hudson SV, Jones JM, Keogh J, Love B. Addressing the needs of cancer survivors during the COVID‐19 pandemic. J Cancer Surviv. Published online April 25, 2020. doi:10.1007/s11764‐020‐00884‐w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Holmes EA, O’Connor RC, Perry VH, et al. Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID‐19 pandemic: a call for action for mental health science. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7:547‐560. doi:10.1016/S2215‐0366(20)30168‐1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Galea S, Merchant RM, Lurie N. The mental health consequences of COVID‐19 and physical distancing. JAMA Intern Med. Published April 10, 2020. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.1562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Barnett M, McDonnell G, DeRosa A, et al. Psychosocial outcomes and interventions among cancer survivors diagnosed during adolescence and young adulthood (AYA): a systematic review. J Cancer Surviv. 2016;10:814‐831. doi:10.1007/s11764‐016‐0527‐6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kosir U, Wiedemann M, Wild J, Bowes L. Psychiatric disorders in adolescent cancer survivors: a systematic review of prevalence and predictors. Cancer Rep. 2019;2:e1168. doi:10.1002/cnr2.1168 [Google Scholar]

- 18. Brooks SK, Webster RK, Smith LE, et al. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. Lancet. 2020;395:912‐920. doi:10.1016/S0140‐6736(20)30460‐8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lowe B, Wahl I, Rose M, et al. A 4‐item measure of depression and anxiety: validation and standardization of the Patient Health Questionnaire‐4 (PHQ‐4) in the general population. J Affect Disord. 2010;122:86‐95. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2009.06.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Lowe B. An ultra‐brief screening scale for anxiety and depression: the PHQ–4. Psychosomatics. 2009;50:613‐621. doi:10.1016/s0033‐3182(09)70864‐3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. R Core Team . R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wickham H. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis. Springer; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wickham H, Francois R, Henry L, Muller K. dplyr: A Grammar of Data Manipulation. Accessed May 13,2020. http://cran.r‐project.org/package=dplyr

- 24. Revelle W. psych: Procedures for Psychological, Psychometric, and Personality Research. Accessed May 13,2020. https://cran.r‐project.org/package=psych

- 25. Aust F, Barth M. papaja: Create APA Manuscripts With R Markdown. Accessed May 13,2020. https://github.com/crsh/papaja

- 26. Krippendorf K. Content Analysis: An Introduction to Its Methodology. 4th ed. Sage Publications Ltd; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Elo S, Kaariainen M, Kanste O, Polkki T, Utriainen K, Kyngas H. Qualitative content analysis. Sage Open. 2014;4:215824401452263. doi:10.1177/2158244014522633 [Google Scholar]

- 28. Boulad F, Kamboj M, Bouvier N, Mauguen A, Kung AL. COVID‐19 in children with cancer in New York City. JAMA Oncol. Published online May 13, 2020. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.2028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Desai A, Sachdeva S, Parekh T, Desai R. Covid‐19 and cancer: lessons from a pooled meta‐analysis. JCO Glob Oncol. 2020;6:557‐559. doi:10.1200/GO.20.00097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Qiu J, Shen B, Zhao M, Wang Z, Xie B, Xu Y. A nationwide survey of psychological distress among Chinese people in the COVID‐19 epidemic: implications and policy recommendations. Gen Psychiatr. 2020;33:19‐21. doi:10.1136/gpsych‐2020‐100213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Casanova M, Bagliacca EP, Silva M, et al. How young patients with cancer perceive the Covid‐19 (coronavirus) epidemic in Milan, Italy: is there room for other fears? Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2020;67:e28318. doi:10.1002/pbc.28318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wilkins KL, D’Agostino N, Penney AM, Barr RD, Nathan PC. Supporting adolescents and young adults with cancer through transitions: position statement from the Canadian Task Force on Adolescents and Young Adults With Cancer. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2014;36:545‐551. doi:10.1097/MPH.0000000000000103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Matthews T, Danese A, Caspi A, et al. Lonely young adults in modern Britain: findings from an epidemiological cohort study. Psychol Med. 2019;49:268‐277. doi:10.1017/S0033291718000788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Greenzang KA, Fasciano KM, Block SD, Mack JW. Early information needs of adolescents and young adults about late effects of cancer treatment. Cancer. 2020;126:3281‐3288. doi:10.1002/cncr.32932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Drew D, Kable A, van der Riet P. The adolescent's experience of cancer: an integrative literature review. Collegian. 2019;26:492‐501. doi:10.1016/j.colegn.2019.01.002 [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ramsey WA, Heidelberg RE, Gilbert AM, Heneghan MB, Badawy SM, Alberts NM. eHealth and mHealth interventions in pediatric cancer: a systematic review of interventions across the cancer continuum. Psychooncology. 2019;29:17‐37. doi:10.1002/pon.5280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Chalmers JA, Sansom‐Daly UM, Patterson P, McCowage G, Anazodo A. Psychosocial assessment using telehealth in adolescents and young adults with cancer: a partially randomized patient preference pilot study. J Med Internet Res. 2018;7:e168. doi:10.2196/resprot.8886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Sansom‐Daly UM, Wakefield CE, Bryant RA, et al. Feasibility, acceptability, and safety of the Recapture Life videoconferencing intervention for adolescent and young adult cancer survivors. Psychooncology. 2019;28:284‐292. doi:10.1002/pon.4938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1‐S4