Abstract

Latest statements from European and American societies recommend to rule out viral presence in endomyocardial biopsy (EMB) via polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis before starting immunosuppression or immunomodulation in acute lymphocytic myocarditis presenting with life‐threatening scenarios. However, recommendations in myocarditis are mostly based on heterogeneous studies enrolling patients with inflammatory cardiomyopathies and established heart failure rather than acute myocarditis. Thus, definitive evidence of a survival benefit from immunomodulation guided by viral presence is currently lacking. Finally, distinguishing innocent bystanders from causative agents among EMB‐detected viruses remain challenging and a major goal to achieve in the near future. Therefore, considerable divergence remains between official recommendations and clinical practice, including the possibility of starting immunosuppressive therapy empirically, without knowing viral PCR results. This review systematically discusses the unsolved issues of immunomodulation guided by viral presence in acute lymphocytic myocarditis, namely (i) virus epidemiology and prognosis, (ii) variability of viral presence rates, (iii) the role of potential viral bystander findings, and (iv) the main results of immunosuppression controlled trials in lymphocytic myocarditis. Furthermore, a practical approach for the critical use of viral presence analysis in guiding immunomodulation is provided, highlighting its importance before starting immunosuppression or immunomodulation. Future, multicentre studies are needed to address specific scenarios such as fulminant lymphocytic myocarditis and a virus‐tailored management as for parvovirus B19.

Keywords: Viral presence, Immunosuppressive therapy, Lymphocytic myocarditis, Endomyocardial biopsy, Polymerase chain reaction

Viral presence: a recommended investigation before immunosuppressive therapy

Myocarditis is an inflammatory disease of the myocardium characterized by great heterogeneity in clinical presentation and natural history, ranging from asymptomatic to rapidly progressive syndromes. 1 Three main clinical scenarios can be encountered: (i) acute clinically unstable or fulminant myocarditis; (ii) acute clinically stable myocarditis; and (iii) chronic myocarditis (i.e. symptoms lasting >6 months). Endomyocardial biopsy (EMB) remains the diagnostic gold standard for myocarditis, due to its definitive diagnosis capacity, particularly in patients presenting challenging clinical scenarios (i.e. acute clinically unstable or fulminant myocarditis). In patients with lymphocytic myocarditis and heart failure (HF) with severe left ventricular dysfunction or life‐threatening ventricular arrhythmias who do not respond to conventional treatments in the short term (i.e. 7–10 days), EMB may guide more advanced medical therapy, including immunosuppression and immunomodulation. 1 Histopathological and immunohistochemical analyses, combined with viral genome presence research via polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis, represent the cornerstones in addressing diagnosis and immunomodulation strategies.

Endomyocardial biopsy recommendations are heterogeneous and have changed significantly over the years, especially regarding the evaluation of viral presence in the cardiomyocytes via PCR analysis to guide immunosuppressive treatment. In the past, official Japanese guidelines 2 and a 2013 statement from the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association (ACCF/AHA) 3 did not recommend routine search for viral genome presence in the myocardium of patients with clinically suspected acute myocarditis. Conversely, the latest myocarditis guidelines from European and American societies specifically define the role of viral search in patients with lymphocytic myocarditis. Indeed, current recommendations by the European Society of Cardiology Working Group on Myocardial and Pericardial Diseases clearly state that ‘immunosuppression should be started only after ruling out active infection on EMB by PCR,’ and, ‘immunosuppression may be considered, on an individual basis, in infection‐negative lymphocytic myocarditis refractory to standard therapy in patients with no contraindications to immunosuppression.’ 4 Accordingly, the latest version of the Cochrane bank analysis reports that ‘corticosteroids may have a role in treating myocarditis without viral evidence.’ 5 The same recommendations have been reaffirmed in recent reviews, where different international experts highlight the need for ruling out viral presence in EMB via PCR analysis before starting immunosuppression or immunomodulation in clinically suspected acute myocarditis patients presenting life‐threatening scenarios. 1 , 6 , 7 These indications have been further confirmed in the latest statement from the AHA, which recommends viral search in clinically suspected acute and fulminant myocarditis. 8 Therefore, viral presence appears relevant in the clinical management of high‐risk lymphocytic myocarditis.

Controversial issues

Immunosuppression appears mandatory in specific non‐infectious myocarditis settings, such as giant cell myocarditis, necrotizing eosinophilic myocarditis and cardiac sarcoidosis. 7 Approximately 90% of the myocarditis cases encountered in clinical practice are lymphocytic, mostly caused by viruses and subsequent immune response. The maladaptive immune response following cardiotropic virus infection has been characterized best in animal models of myocarditis sustained by enteroviruses. 6 Coxsackievirus groups A and B, belonging to the enteroviruses, were shown to enter within cardiomyocytes via the transmembrane coxsackievirus and adenovirus receptor and to induce rapid cytolysis due to pronounced viral replication. 9 The potential mechanisms of direct cardiac damage induced by other non‐enteroviruses are less defined. 9 In recent genome‐wide association studies, specific genetic loci and innate and acquired immune response pathways have been associated with human host responses against infectious diseases, 10 especially HLA variants. These findings were not confirmed in the study by Belkaya et al., 11 where genetic mutations in interferon‐mediated immunity investigated in human‐induced pluripotent stem cell‐derived cardiomyocytes did not result in increased susceptibility to viral myocarditis, though the study did note a potential association between myocarditis and defects in cardiac structural proteins. Available evidence is clearly heterogeneous and further research on the pathophysiological mechanisms of viral heart damage is required, mostly regarding autoimmune reactions and genetically defined host factors. Furthermore, distinguishing innocent bystanders from causative myocarditis agents, among EMB‐detected viruses, is of utmost importance to address tailored therapy. However, this is a challenging task to pursue and a major goal to achieve in the near future. Currently, viral presence in the myocardium is a pathological finding; the only exception is parvovirus B19 (PVB19), which, particularly at low viral burden, has been reported in non‐inflammatory cardiac disease as well, 12 and also requires further research.

In myocarditis, recommendations are mostly based on small and heterogeneous studies that enrolled patients with inflammatory cardiomyopathies and established HF; any definitive evidence of a survival benefit from immunomodulation is currently lacking. 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 Particularly in the minority of patients with clinically suspected acute myocarditis and positive viral presence upon PCR analysis, antiviral drugs 19 , 20 and intravenous immunoglobulins (IVIG) 21 were shown to be well‐tolerated and increase viral clearance. 4 However, controlled adult IVIG therapy experiences are limited. 8

Immunosuppression guided by comprehensive EMB analysis may be considered in myocarditis with high‐risk presentation, such as fulminant myocarditis, acute HF, electrical instability due to life‐threatening ventricular arrhythmias and, rarely, patients with recurrent acute myocarditis and persistently elevated serum troponin. Still, the value of immunosuppression in these scenarios has never been investigated in dedicated trials.

Therefore, considerable divergence remains between official recommendations and clinical practice, and some Centres start immunosuppressive therapy empirically, without knowing the PCR results on viral presence in the myocardium. 22 This practice is mainly supported by data from a retrospective Italian registry, including a highly selected population of patients with clinically acute myocarditis. EMB was performed for most of the patients with fulminant myocarditis and only a minority of them were treated without knowing EMB results. Furthermore, molecular virus search via PCR analysis was not systematically performed and the implications of the presence of specific viruses for clinical management and prognosis could not be investigated. 22

The following are the main observations to consider when conducting molecular analysis in EMB samples.

Virus epidemiology and prognosis

In 2007, Caforio et al. 23 demonstrated an association between viral presence (mostly enteroviruses) and increased mortality at univariate analysis of an Italian cohort. Although the researchers found a negligible PVB19 frequency, they did not systematically investigate this virus presence. Conversely, Kindermann et al. 24 in 2008 reported a higher frequency of PVB19 and/or human herpes virus 6 (HHV‐6) detection in a consecutive German cohort, but viral presence did not emerge as independently associated with survival upon multivariate analysis. These studies show a temporal shift in virus epidemiology, in particular the lower frequency of enteroviruses in the latest cohorts and a high PVB19 frequency in Germany. These studies are not comparable, though, since the two cohorts' viral epidemiology was different. However, these discrepancies partially derive from a more extensive search for the PVB19 viral genome, resulting from the heightened awareness of PVB19 as a potential viral agent in myocarditis over time; therefore, its prevalence in the Italian cohort might have been reasonably underestimated. The increased awareness over time of causative viral myocarditis agents due to molecular EMB analysis yields a more accurate characterization of virus‐tailored clinical management of patients.

Lastly, enteroviruses are established viral myocarditis causative agents in animals and in humans 9 ; conversely, the role of other viruses (particularly PVB19 and HHV‐6) is at present controversial and requires further scrutiny.

Variability of viral presence rates

Genome sequences of more than 27 viruses have been detected in hearts with myocarditis, including coxsackievirus groups A and B, echovirus, human immunodeficiency virus 1, herpes simplex virus and hepatitis A and C. 25 , 26 Influenza A and B viruses can trigger myocarditis, but their roles as direct causes of myocarditis have yet to be assessed. Although viral infection remains the most likely first cause of lymphocytic myocarditis in clinical practice, PCR analyses are negative in most cases, excluding PVB19. 25 , 27 Conversely, in the chronic HF setting, due to dilated cardiomyopathy, a viral presence can be found in 67% of cases (mostly PVB19) upon EMB via PCR analysis, with 27% having dual or multiple infections in the myocardium from different viral agents. 28

The contemporary PCR analysis for viral presence in EMB specimens and blood samples should always be investigated, as this technique is the gold standard to rule out the possibility of tissue contamination. The absence of a viral genome in a blood sample greatly reduces the likelihood of passive blood contamination of EMB specimen. The presence of a viral genome in both samples requires further investigation through quantitative PCR analysis to assess the viral load. 4

Most currently, the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19), caused by SARS‐CoV‐2, has emerged as a potential cause of myocarditis, mostly due to an important cytokine release and immune response. 29 SARS‐CoV‐2 particles have recently been reported at EMB in macrophages of the interstitial space via electromicroscopy, 30 but no particles were detected in cardiomyocytes and viral PCR was negative. Therefore, the evidence of direct cardiac involvement of SARS‐CoV‐2 is still lacking. As a consequence, the implications of viral presence upon EMB need to be assessed in future studies and might be limited, at present, to highly selected, life‐threatening acute scenarios.

As such, viral PCR analysis in EMB samples should be performed on a regular basis to better characterize the pathological substrate causing myocarditis and to guide clinical decision‐making.

Role of potential viral bystander findings

The operative implications of PVB19 remain uncertain. 15 , 25 PVB19 is the most frequently detected virus in PCR analyses, 23 having appeared in 33–64% of cases across different studies. 6 , 25 However, similar percentages of PVB19‐positive analyses have been demonstrated in patients with non‐inflammatory cardiomyopathy (i.e. ischaemic or valvular heart disease) who were undergoing cardiac surgery, 12 bringing the role of PVB19 as a pathogenic agent or innocent bystander into question. For this reason, PCR‐based quantification of viral genomes and replicative status is required, mostly for PVB19, before starting immunosuppression. On the one hand, low‐copy PVB19 may enable the initiation of steroid therapy, 15 but on the other, patients with severe systemic PVB19 infections presenting with fulminant myocarditis can have a high viral load (> 500 copies/µg DNA) that prevents immunosuppressive drug administration, due to the risk of uncontrolled infection. Therefore, the differentiation between high and low viral loads is quite important. As reported by Bock et al., 31 the mean PVB19 viral load found in EMB specimens in clinically acute myocarditis is substantially higher than that detected in chronic myocarditis (709 vs. 316 copies/µg DNA), thus suggesting its potential to trigger and foster persistent infection and inflammation.

Although recognized as a causative viral agent, the pathophysiological mechanisms of HHV‐6 in acute myocarditis remain to be assessed. 9 The HHV‐6 genome can be found in up to 20% of myocardial samples from subjects with myocarditis or dilated cardiomyopathy, but it rarely causes severe myocarditis in immunocompetent hosts. 9 However, when it does, fulminant hepatitis may be associated with it, and patients may face a fatal outcome accordingly. 32 Further, conventional treatment of HHV‐6 positive myocarditis consists of acyclovir administration, and steroid therapy should be avoided due to a subsequent increase in viral load. 9

Currently, there are cut‐off values for the viral quantification of PVB19 (> 500 copies/µg DNA) 31 , 33 , 34 and HHV‐6 (> 500 copies/µg DNA). 7 These are considered clinically relevant thresholds for the maintenance of myocardial inflammation. Still, future research is required to better define the virus‐specific cut‐off values to distinguish innocent bystanders from real pathogenic agents and to confirm their implications for patient management.

Immunosuppression controlled trials in lymphocytic myocarditis

Previous studies investigating immunosuppression in patients with lymphocytic myocarditis were often retrospective and characterized by great heterogeneity in inclusion criteria, immunosuppressive regimens, pre‐specified endpoints and follow‐up time. 18 , 35 Among prospective studies, the Myocarditis Treatment Trial 16 randomized 111 patients with biopsy‐proven myocarditis with left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) < 45% and HF during the 2 years preceding their enrolment to receive immunosuppressive therapy (prednisone with either cyclosporine or azathioprine) or conventional treatment for 24 weeks. At 28 weeks, no significant changes in LVEF or survival benefits were found between groups. However, the population was largely unselected in terms of aetiologic substrate, grade of inflammatory activation, viral genome presence and virus type. Indeed, the investigators enrolled patients without knowing viral presence or absence on EMB. More recently, the TIMIC study 14 enrolled a well‐selected population of 85 patients with histologically confirmed, virus‐negative myocarditis with LVEF <45% and > 6 months of chronic HF (including New York Heart Association classes III and IV) who were unresponsive to maximal tolerable doses of conventional medical therapy. The TIMIC study implemented standard histological criteria with positive immunohistochemical analysis and negative PCR results on an extensive virus panel to selectively address immunosuppression vs. placebo in patients with myocarditis. Although this study did not report data on hard endpoints, such as mortality, at 6 months, 88% of the patients treated with immunosuppressive therapy had significant left ventricular reverse remodelling. 14 Of note, the lack of response to immunosuppressive therapy was found in 5 (12%) out of 43 patients, suggesting the presence of alternative mechanisms of myocardial damage that are not adequately targeted by immunosuppression.

Therefore, the rational indication to immunosuppression is based on the presence of biopsy‐proven, infection‐negative active myocarditis and its specific aetiology, 8 regardless of clinical presentation (both recent‐onset and chronic HF). However, it must be acknowledged that more data about immunosuppression in myocarditis with HF symptoms developed <6 months (acute or fulminant presentations) should be gathered; as such, controlled studies in this population are strongly advocated.

Future perspectives: a long way to go

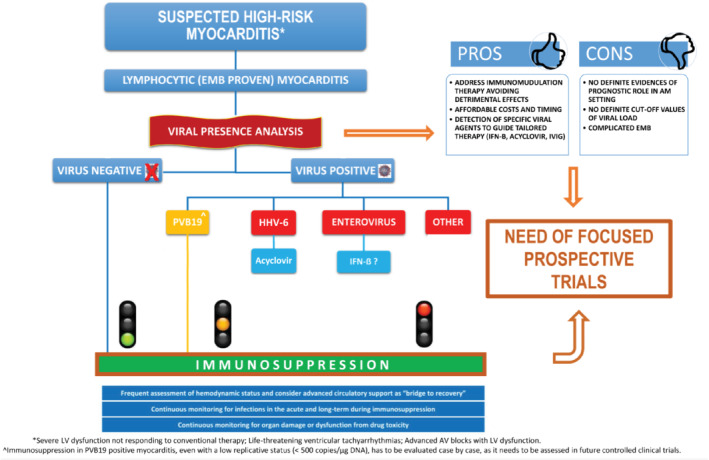

Patient‐tailored diagnostics and therapeutic management are required, as immunosuppression carries a non‐negligible risk of potentially major complications, including the suppression of appropriate immunologic response and the subsequent worsening of myocardial injury, an increase and proliferation of secondary ‘opportunistic’ infections and drug‐related toxicity. Knowledge of viral genome presence may influence therapeutic choices. In this perspective and also considering its viable costs and reasonable wait time, PCR‐based viral genome quantification in biopsy‐proven lymphocytic myocarditis should not be restricted in its application (Figure 1 ). At our institution, PCR results are available within 48–72 h for the majority of viruses, with the exception of enterovirus and PVB19, which require five working days due to virus‐specific features. Costs vary depending on the number of viruses being tested but all are easily affordable at third level centres, considering that just a few hundred euros are generally needed. Selecting the appropriate EMB timing is crucial as viral clearance increases after the acute phase. However, this procedure is burdened by a mild yet relevant rate of major complications (around 1%) even in experienced centres. 1 Myocardial samples can be collected from different sites in the left ventricle, right ventricle or interventricular septum with variable diagnostic accuracy. Regardless of collection site, however, it is crucial to obtain an adequate number (≥4) of tissue samples and to preserve them appropriately. 1 Therefore, EMB performed early in clinical presentation usually offers the most accurate diagnostic information. 6 In addition, although very little data are currently available, the replicative activity of viruses causing myocarditis could be a further element to consider, along with viral genome quantification when evaluating patients' eligibility to immunosuppression. Active viral replication might represent a contraindication to immunosuppression. In this respect, viral load quantification could prove important, mostly in PVB19‐positive patients. Although PCR analysis allows quantification of viral load and replicative status from EMB specimens, this technique lacks standardization, as different protocols can be adopted. In addition, inter‐laboratory variability and the absence of definite cut‐off values for ‘significant’ viral load and viral replication require cautious interpretation of results. Procedural standardization among different laboratories and future focused research are thus required (Figure 1 ).

Figure 1.

Critical proposal for an operative flow‐chart to guide immunosuppressive treatment in high‐risk lymphocytic myocarditis. Immunosuppression supported by current evidence (in green); knowledge gap in scientific literature about immunosuppression (in orange); immunosuppression contraindicated because of potential harm and/or lack of evidence (in red). Viral load by quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is measured in copies/µg DNA. AM, acute myocarditis; AV, atrio‐ventricular; EMB, endomyocardial biopsy; HHV‐6, human herpesvirus 6; IFN‐B, interferon beta; IVIG, intravenous immunoglobulins; LV, left ventricular; PVB19, parvovirus B19.

For the abovementioned reasons, the exclusion of viral presence before starting full immunosuppressive therapy (i.e. azathioprine and corticosteroids for at least 6 months) in lymphocytic myocarditis is recommended. This might decrease potential side effects, such as uncontrolled virus replication, subsequent active infection and additional global clinical deterioration, that are possibly life‐threatening in high‐risk patients with lymphocytic myocarditis. 18 Notably, in highly selected patients presenting with severe fulminant myocarditis and who require temporary advanced mechanical circulatory support systems, 1 early immunosuppression may be crucial to survival. In this setting, a prompt EMB, including viral search, is recommended and the initiation of partial immunosuppressive treatment (e.g. pulse steroid therapy) while obtaining PCR results might represent a reasonable approach. 33 The subsequent decision of whether to implement or discontinue immunosuppression may be deferred after eventual virus detection.

The value of viral presence to guide immunosuppressive treatment in patients with lymphocytic myocarditis requires more evidence and remains a subject of debate among experts, especially when considering the different clinical impact of viruses. 33 In particular, the possibility of immunosuppression in PVB19‐positive myocarditis, especially with a low replicative status, needs to be assessed in future controlled clinical trials (Figure 1 ).

Therefore, future consensus documents and, mostly, dedicated randomized controlled trials will be pivotal in establishing the role of viral presence in guiding immunomodulation in lymphocytic myocarditis.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Fondazione CRTrieste, Fondazione CariGO, Fincantieri and all the healthcare professionals for the continuous support to the clinical management of patients affected by cardiomyopathies and myocarditis. Furthermore, we would like to thank all the patients and their families, the nurses and the doctors who refer patients to the Cardiomyopathies Center of Trieste.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

References

- 1. Sinagra G, Anzini M, Pereira NL, Bussani R, Finocchiaro G, Bartunek J, Merlo M. Myocarditis in clinical practice. Mayo Clin Proc 2016;91:1256–1266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. JCS Joint Working Group . Guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of myocarditis (JCS 2009). Circ J 2011;75:734–743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, Butler J, Casey DE, Drazner MH, Fonarow GC, Geraci SA, Horwich T, Januzzi JL, Johnson MR, Kasper EK, Levy WC, Masoudi FA, McBride PE, McMurray JJV, Mitchell JE, Peterson PN, Riegel B, Sam F, Stevenson LW, Tang WH, Tsai EJ, Wilkoff BL. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013;62:e147–e239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Caforio AL, Pankuweit S, Arbustini E, Basso C, Gimeno‐Blanes J, Felix SB, Fu M, Helio T, Heymans S, Jahns R, Klingel K, Linhart A, Maisch B, McKenna W, Mogensen J, Pinto YM, Ristic A, Schultheiss HP, Seggewiss H, Tavazzi L, Thiene G, Yilmaz A, Charron P, Elliott PM. Current state of knowledge on aetiology, diagnosis, management, and therapy of myocarditis: a position statement of the European Society of Cardiology Working Group on Myocardial and Pericardial Diseases. Eur Heart J 2013;34:2636–2648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chen HS, Wang W, Wu SN, Liu JP. Corticosteroids for viral myocarditis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;(10):CD004471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pollack A, Kontorovich AR, Fuster V, Dec GW. Viral myocarditis‐diagnosis, treatment options, and current controversies. Nat Rev Cardiol 2015;12:670–680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Heymans S, Eriksson U, Lehtonen J, Cooper LT. The quest for new approaches in myocarditis and inflammatory cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016;68:2348–2364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kociol RD, Cooper LT, Fang JC, Moslehi JJ, Pang PS, Sabe MA, Shah RV, Sims DB, Thiene G, Vardeny O. Recognition and initial management of fulminant myocarditis: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2020;141:e69–e92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Pankuweit S, Klingel K. Viral myocarditis: from experimental models to molecular diagnosis in patients. Heart Fail Rev 2013;18:683–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chapman SJ, Hill AV. Human genetic susceptibility to infectious disease. Nat Rev Genet 2012;13:175–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Belkaya S, Kontorovich AR, Byun M, Mulero‐Navarro S, Bajolle F, Cobat A, Josowitz R, Itan Y, Quint R, Lorenzo L, Boucherit S, Stoven C, Di Filippo S, Abel L, Zhang SY, Bonnet D, Gelb BD, Casanova JL. Autosomal recessive cardiomyopathy presenting as acute myocarditis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017;69:1653–1665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Moimas S, Zacchigna S, Merlo M, Buiatti A, Anzini M, Dreas L, Salvi A, Di Lenarda A, Giacca M, Sinagra G. Idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy and persistent viral infection: lack of association in a controlled study using a quantitative assay. Heart Lung Circ 2012;21:787–793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wojnicz R, Nowalany‐Kozielska E, Wojciechowska C, Glanowska G, Wilczewski P, Niklewski T, Zembala M, Poloński L, Rozek MM, Wodniecki J. Randomized, placebo‐controlled study for immunosuppressive treatment of inflammatory dilated cardiomyopathy. Circulation 2001;104:39–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Frustaci A, Russo MA, Chimenti C. Randomized study on the efficacy of immunosuppressive therapy in patients with virus‐negative inflammatory cardiomyopathy: the TIMIC study. Eur Heart J 2009;30:1995–2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tschöpe C, Elsanhoury A, Schlieker S, Van Linthout S, Kühl U. Immunosuppression in inflammatory cardiomyopathy and parvovirus B19 persistence. Eur J Heart Fail 2019;21:1468–1469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mason JW, O'Connell JB, Herskowitz A, Rose NR, McManus BM, Billingham ME, Moon TE. A clinical trial of immunosuppressive therapy for myocarditis. The Myocarditis Treatment Trial Investigators. N Engl J Med 1995;333:269–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. De Luca G, Campochiaro C, Sartorelli S, Peretto G, Sala S, Palmisano A, Esposito A, Candela C, Basso C, Rizzo S, Thiene G, Della Bella P, Dagna L. Efficacy and safety of mycophenolate mofetil in patients with virus‐negative lymphocytic myocarditis: a prospective cohort study. J Autoimmun 2020;106:102330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Frustaci A, Chimenti C, Calabrese F, Pieroni M, Thiene G, Maseri A. Immunosuppressive therapy for active lymphocytic myocarditis. Circulation 2003;107:857–863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kühl U, Lassner D, von Schlippenbach J, Poller W, Schultheiss HP. Interferon‐beta improves survival in enterovirus‐associated cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol 2012;60:1295–1296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Schultheiss HP, Piper C, Sowade O, Waagstein F, Kapp JF, Wegscheider K, Groetzbach G, Pauschinger M, Escher F, Arbustini E, Siedentop H, Kuehl U. Betaferon in Chronic Viral Cardiomyopathy (BICC) trial: effects of interferon‐β treatment in patients with chronic viral cardiomyopathy. Clin Res Cardiol 2016;105:763–773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. McNamara DM, Holubkov R, Starling RC, Dec GW, Loh E, Torre‐Amione G, Gass A, Janosko K, Tokarczyk T, Kessler P, Mann DL, Feldman AM. Controlled trial of intravenous immune globulin in recent‐onset dilated cardiomyopathy. Circulation 2001;103:2254–2259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ammirati E, Cipriani M, Lilliu M, Sormani P, Varrenti M, Raineri C, Petrella D, Garascia A, Pedrotti P, Roghi A, Bonacina E, Moreo A, Bottiroli M, Gagliardone MP, Mondino M, Ghio S, Totaro R, Turazza FM, Russo CF, Oliva F, Camici PG, Frigerio M. Survival and left ventricular function changes in fulminant versus nonfulminant acute myocarditis. Circulation 2017;136:529–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Caforio AL, Calabrese F, Angelini A, Tona F, Vinci A, Bottaro S, Ramondo A, Carturan E, Iliceto S, Thiene G, Daliento L. A prospective study of biopsy‐proven myocarditis: prognostic relevance of clinical and aetiopathogenetic features at diagnosis. Eur Heart J 2007;28:1326–1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kindermann I, Kindermann M, Kandolf R, Klingel K, Bültmann B, Müller T, Lindinger A, Böhm M. Predictors of outcome in patients with suspected myocarditis. Circulation 2008;118:639–648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mahfoud F, Gartner B, Kindermann M, Ukena C, Gadomski K, Klingel K, Kandolf R, Bohm M, Kindermann I. Virus serology in patients with suspected myocarditis: utility or futility? Eur Heart J 2011;32:897–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Liu ZL, Liu ZJ, Liu JP, Kwong JS. Herbal medicines for viral myocarditis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;(8):CD003711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Dennert R, Crijns HJ, Heymans S. Acute viral myocarditis. Eur Heart J 2008;29:2073–2082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kühl U, Pauschinger M, Noutsias M, Seeberg B, Bock T, Lassner D, Poller W, Kandolf R, Schultheiss HP. High prevalence of viral genomes and multiple viral infections in the myocardium of adults with ‘‘idiopathic’’ left ventricular dysfunction. Circulation 2005;111:887–893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Inciardi RM, Lupi L, Zaccone G, Italia L, Raffo M, Tomasoni D, Cani DS, Cerini M, Farina D, Gavazzi E, Maroldi R, Adamo M, Ammirati E, Sinagra G, Lombardi CM, Metra M. Cardiac involvement in a patient with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19). JAMA Cardiol 2020;5:1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Tavazzi G, Pellegrini C, Maurelli M, Belliato M, Sciutti F, Bottazzi A, Sepe PA, Resasco T, Camporotondo R, Bruno R, Baldanti F, Paolucci S, Pelenghi S, Iotti GA, Mojoli F, Arbustini E. Myocardial localization of coronavirus in COVID‐19 cardiogenic shock. Eur J Heart Fail 2020;22:911–915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bock CT, Klingel K, Kandolf R. Human parvovirus B19‐associated myocarditis. N Engl J Med 2010;362:1248–1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ashrafpoor G, Andréoletti L, Bruneval P, Macron L, Azarine A, Lepillier A, Danchin N, Mousseaux E, Redheuil A. Fulminant human herpesvirus 6 myocarditis in an immunocompetent adult. Circulation 2013;128:e445–e447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Veronese G, Ammirati E, Brambatti M, Merlo M, Cipriani M, Potena L, Sormani P, Aoki T, Sugimura K, Sawamura A, Okumura T, Pinney S, Hong K, Shah P, Braun OÖ, Van de Heyning CM, Montero S, Petrella D, Huang F, Schmidt M, Raineri C, Lala A, Varrenti M, Foà A, Leone O, Gentile P, Artico J, Agostini V, Patel R, Garascia A, Van Craenenbroeck EM, Hirose K, Isotani A, Murohara T, Arita Y, Sionis A, Fabris E, Hashem S, Garcia‐Hernando V, Oliva F, Greenberg B, Shimokawa H, Sinagra G, Adler ED, Frigerio M, Camici PG. Viral genome search in myocardium of patients with fulminant myocarditis. Eur J Heart Fail 2020;22:1277–1280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lotze U, Egerer R, Glück B, Zell R, Sigusch H, Erhardt C, Heim A, Kandolf R, Bock T, Wutzler P, Figulla HR. Low level myocardial parvovirus B19 persistence is a frequent finding in patients with heart disease but unrelated to ongoing myocardial injury. J Med Virol 2010;82:1449–1457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Merlo M, Gentile P, Ballaben A, Artico J, Castrichini M, Porcari A, Cannatà A, Perkan A, Bussani R, Sinagra G. Acute inflammatory cardiomyopathy: apparent neutral prognostic impact of immunosuppressive therapy. Eur J Heart Fail 2020;22:1280–1282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]