Conversion of a busy inpatient oncology service that typically treats more than 5,000 patients a year to units caring for patients with COVID‐19 is a story of teamwork and resilience.

Warning Bells

Even before SARS‐CoV‐2 had officially arrived on U.S. shores, our hospital, like many others, had started to prepare. We engaged in modeling impact on hospital capacity, obtaining personal protective equipment, securing ventilators, and organizing a military‐like operation to prepare for the possibility of a pandemic. These models predicted that hospitals throughout our area would face a surge of inpatients, the volume of which would be unlike anything witnessed in our lifetimes.

In early March, the hospital recommended a dramatic increase in the number of inpatient and intensive care unit (ICU) beds devoted to patients with COVID‐19. It followed that we would need a similar dramatic increase in staffing to cover this surge of patients.

Coordinating Our Response

In a phased approach, the institution closed nonessential services, transferred pediatric patients to nearby medical centers, and began to train those who would provide COVID‐19 care. These efforts ensured that 12 hospital floors (307 beds) and nine intensive care units (179 beds) could be dedicated to COVID‐19 care, representing a 35% increase in our general medicine and a 400% increase in our regular ICU bed capacity. Surge ICU space was created from two postanesthesia care units, one perioperative care area, one 32‐bed oncology floor, and a 32‐bed neurology floor.

Staffing of these floors by the usual complement of residents, fellows, and hospitalists would not be sufficient to meet this demand and plans for additional staffing were quickly implemented. Our Division of Hematology/Oncology was among the subspecialties that volunteered to the Department of Medicine effort, and we recruited colleagues from neuro‐oncology and from community satellite clinics. At our side would be numerous residents and fellows—trainees who would be sorely tested and who would later reflect on both the unfathomable terror and enormous benefit of the experience.

Training for the New War

Before our medical oncologists could join in the fight on the COVID‐19 units, training had to be completed, floors and ICUs readied, and rotations scheduled. All of this happened within days, or sometimes within hours. In parallel, each subspecialty was tasked to grapple with the outpatient transition from in‐person to virtual care. Nowhere was the impact of this transition felt more acutely than in the cancer center, where in‐person visits are frequent and many patients require care that cannot be given remotely. Clinic schedules were rearranged to minimize the number of providers required in our outpatient clinics to accommodate inpatient service deployment.

One of our responsibilities was to prepare the first wave of oncologists who would treat the COVID‐19 surge of patients. Beyond the fact that this was unnerving and unfamiliar, we also had to think about admission order sets, medication reconciliation, and completing discharge modules—all within the context of an electronic medical record system that had not existed a few years before. Many of us were years beyond internal medicine board certification and deep into subspecialty careers, with the days of performing arterial blood gas checks and removing central lines a distant memory.

On top of needing an Intern 101 refresher, we also needed fluency in the rapidly changing language of COVID‐19—identifying risk factors, categorizing patients with severe disease, determining when to use certain drugs, treating coinfections, and discussing antiviral clinical trials with patients—all while understanding that there was a lot that we simply did not know about this new disease.

Our oncology team would eventually take over the 24‐hour staffing of three COVID‐19 units. Some of us would cover the overnight shifts, which was a radical change from our usual daytime routines. In considering schedules, it was imperative to ascertain the needs of each provider with regard to personal health issues, parenting/caregiving responsibilities, and myriad other factors. We took into consideration the possibility that many individuals might become ill or need time out of work. With these layers of information, we built a schedule to include five layers of backup on every given day.

Confounding this complicated plan was the uncertain timetable of the virus! When would the surge of ICU patients hit a peak? How long would patients require hospitalization? Would we be overstaffed or understaffed? Despite our perceived careful planning, it often remained impossible to respond to the unanticipated operational oscillations that would suddenly appear and demand immediate attention.

The challenge of implementing such wide‐sweeping changes was anticipated to be a little rocky, particularly because patient lives were at stake and because providers were facing a deadly and contagious disease. Our operational and logistical plans had to be seamless with the important goal of delivering care proficiently and safely.

Voices from Oncology Staff at the Front

One of the challenges in treating COVID‐19 was in learning how to correctly don and doff our personal protective equipment (PPE). Unfamiliar, unwieldy, time‐consuming, and uncomfortable, the correct use of PPE was nonetheless essential in minimizing self‐contamination.

“Wearing the PPE is exhausting; it takes this constant vigilance.”

We became acquainted with the “cytokine storm” seen in certain severe cases. Even those of us well‐versed in addressing the adverse reactions seen in our patients on immunotherapy were in unfamiliar territory and lacking in therapeutics.

“The scope and manifestations of COVID‐19 symptoms were overwhelming.”

“For patients with COVID‐19, it's often a helpless feeling. There are no effective treatments, and you feel that you are not doing enough.”

Facing the Enemy

When the moment came, our first oncology ward transitioned to a COVID‐19 unit in 3 frenzied hours. The pace was staggering. The roles for oncologists were initially at the attending level, but as need grew by the second week, we became responding clinicians across the general units and ICUs.

“The fellows and residents noticed that it's good for morale to have attending physicians working side by side with them, doing the same job, and with the same uncertainty about this disease. From our standpoint as attendings, it's a privilege to work with our trainees and we learn as much (or more) from them as they from us. The nursing and support staff have worked hardest of all, with the most responsibility. They have led the way with compassion and kindness, and we just try to follow in kind.”

Despite the dedication and deep caring of our oncologists, we recognized our limitations as internists and there remained the deeply unsettling question of whether we could adequately care for these vulnerable patients.

“It had been years since I had been involved in clinical care in the ICU. The team approach of the ICU allowed each of us to contribute our individual skillsets and to support one another during such a challenging time. I've never been prouder of my colleagues and of our profession.”

One of our biggest initial challenges was in overcoming fear. We were fearful of becoming infected ourselves, fearful of transporting the virus back home to our families, fearful of a patient's cough or sneeze, and fearful of touching anything without the proper protection. This fear was pervasive and, at times, paralyzing. In an incredible show of unity, not one person without a compelling home situation or personal health exception declined to participate.

“The only thing more formidable than the fear we have faced over the last several weeks is the overwhelming sense of compassion, connection, and teamwork.”

Early on, it was evident that there were racial and socioeconomic disparities in the population affected and admitted with severe COVID‐19. We saw a high proportion of Hispanics and adapted our teams to include at least one Spanish‐speaking physician in addition to normal translator services.

“Being alone in the hospital with an unfamiliar disease was hard for all patients and probably more so for those that spoke only Spanish. Being bilingual gave me a chance to directly connect and to feel grateful that I could advocate for my patients during this challenging time.”

As visitors to the hospital were strictly prohibited, we faced the challenge of engaging with patients and their families via telephone and teleconferences. This flew in the face of our normal inpatient oncology care, where one might sit on the side of a patient's bed or perhaps just stay in the room and listen to the family chat among each other. This terrible burden of loneliness only added to the anxiety and suffering of our sick patients and their home‐bound families.

“Patients on the COVID units faced this illness alone, without family or friends, separated from their care providers by layers of PPE. Finding ways to provide a more tangible, human connection—while also minimizing my exposure—was a challenge I faced every day.”

From the onset, we had to quickly adapt to ever‐changing recommendations and working conditions. We were not only learning about an entirely new disease but also doing so in the context of new wards with new teams and an evolving schedule.

“I quickly learned that my go‐to style of leadership—relying on the deliberate building of consensus—does not work well in a pandemic. During the COVID‐19 surge, the rapid messaging made it was impossible to engage in my customary manner. We faced a reality outside of our normal routines and had to adapt, carry on, and rely on each other.”

Uniting to Fulfill a New Calling

At the peak, we staffed three COVID‐19 units, day and night. Ninety‐four highly specialized academic oncologists served over 750 surge shifts and over 130 shifts in the COVID‐19 ICU. These 12‐hour shifts were stacked on top of inpatient responsibilities and outpatient virtual appointments.

At the outset, we did not ponder how well‐suited oncologists are for a pandemic. Oncologists attempt to marry compassionate care with up‐to‐date research. We encounter multiorgan involvement and regularly see patients in critical condition. The general framework of multidisciplinary team care translated well onto the COVID‐19 wards and to this different type of patient who required simultaneous management by inpatient medicine, infectious disease, and pulmonary teams. Furthermore, because of the unpredictable nature of cancer, oncologists are accustomed to dealing with unknowns, adjusting and considering alternate treatments as a patient's disease progresses. In practicing the art of oncology, we tried to guide our patients and their families through these trying times with empathy and clear communication. All of these skills were invaluable during the inpatient battle with COVID‐19.

“COVID‐19 is marked by relentless loneliness and fear. These emotions are experienced by individuals, families, and communities. In the face of this, we mobilized our best skills as oncologists to provide individualized and compassionate care, while supporting each other as colleagues and friends.”

Reaching the Other Side

We wanted to be brave—to stare down the unknown and provide care for our patients in the most adverse circumstances—and manage to stay strong while doing so. The reality is that we were often uncertain, anxious, and concerned. But we found strength and resilience as a team and supported each other in addressing and overcoming our fears.

As the first inpatients recovered and were discharged (as of June 23, 2020, there have been 1,510 individuals), a sense of relief started to replace the fear. This group of oncologists‐turned‐interns demonstrated that they possessed the skills to step into an uncertain situation and care for a new patient population.

“It was humbling to take care of patients with COVID‐19. More than ever we needed compassion and emotional connectivity with our patients and their families battling this devastating and isolating disease.”

June 10, 2020, marked the end of the oncology surge effort and a time to reflect on the previous 83 days. It was truly a team effort; physicians from all disciplines, nurses, nurse practitioners, residents, fellows, interpreter services, environmental services, dietary services, patient transport, and administrators were all critical. This experience made us better, stronger, and more human. By employing the art of oncology, we helped in a time of great need and remain prepared for whatever the future may bring. We now know that, together, we can face danger and enormous uncertainty and still find safe harbor on the other side.

Disclosures

Samuel J. Klempner: Merck, Eli Lilly, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Pieris, Foundation Medicine, Boston Biomedical (C/A), Turning Point Therapeutics (OI); Ephriam P. Hochberg: Leuko and Travelling, TRAPelo (C/A); Meghan J. Mooradian: AstraZeneca, Necktar Pharmaceuticals, Immunai (C/A); Richard J. Lee: Janssen (RF), Bayer, Dendreon, GE, Exelixis (SAB); David B. Sykes: Clear Creek Bio (OI); Aditya Bardia: Pfizer, Novartis, Genentech, Merck, Radius Health, Immunomedics, Taiho, Sanofi, Diiachi Pharma/Astra Zeneca, Puma, Biothernostics Inc., Phillips, Eli Lilly, Foundation Medicine (C/A), Genentech, Novartis, Pfizer, Merck, Sanofi, Radius Health, Immunomedics, Diiachi Pharma/AstraZeneca (RF [institutional]); Rachel P. Rosovsky: Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Janssen (RF [institutional]), Bristol‐Myers Squibb. Janssen. Portola, Dova (C/A); David P. Ryan: MPM Capital, Acworth Pharmaceuticals, Thrive Earlier Detection (OI), MPM Capital, Oncorus, Gritstone Oncology, Maverick Therapeutics, 28/7 Therapeutics (C/A), Johns Hopkins University Press, Uptodate, McGraw Hill (Other: publishing). The other authors indicated no financial relationships.

(C/A) Consulting/advisory relationship; (RF) Research funding; (E) Employment; (ET) Expert testimony; (H) Honoraria received; (OI) Ownership interests; (IP) Intellectual property rights/inventor/patent holder; (SAB) Scientific advisory board

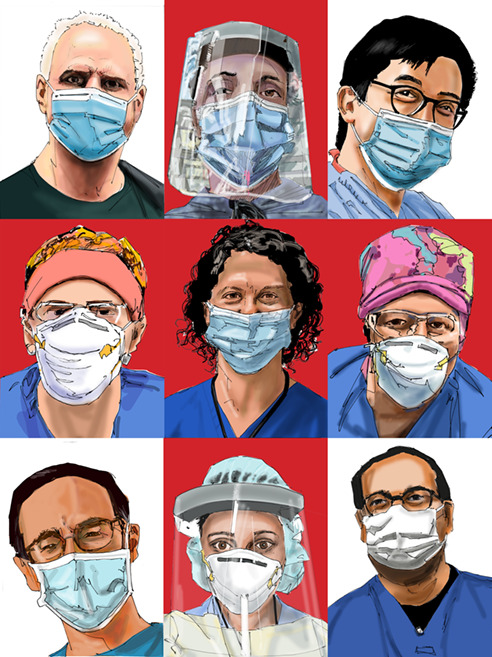

Credit: Robert Biedrzycki

Disclosures of potential conflicts of interest may be found at the end of this article.

No part of this article may be reproduced, stored, or transmitted in any form or for any means without the prior permission in writing from the copyright holder. For information on purchasing reprints contact Commercialreprints@wiley.com. For permission information contact permissions@wiley.com.