Abstract

Objective. The purpose of this study was to develop, pilot, and validate a situational judgement test (SJT) to assess professionalism in Doctor of Pharmacy (PharmD) students.

Methods. Test specifications were developed and faculty members were educated on best practices in item writing for SJTs. The faculty members then developed 75 pilot scenarios. From those, two versions of the SJT, each containing 25 scenarios, were created. The pilot population for the SJT was student pharmacists in their third professional year, just prior to starting their advanced pharmacy practice experiences. The students completed the two versions of the test on different days, approximately 48 hours apart, with 50 minutes allowed to complete each. Subsequently, students completed a questionnaire regarding the SJT at the conclusion of the second test.

Results. Version 1 of the SJT was completed by 228 students, and version 2 was completed by 225 students. Mean scores were 390 (SD=20, range 318-429) and 342 (SD=21, range 263-387) on test versions 1 and 2, respectively. The reliability of the tests was appropriate (test version 1, α=0.77; test version 2, α=0.79). Students felt that the content of the tests was realistic with respect to pharmacy practice (90.1%), and that the tests gave them an opportunity to reflect on how to approach challenging situations (82.6%).

Conclusion. We developed a reliable SJT to assess professionalism in PharmD students. Future research should focus on creating a personalized learning plan for students who do not meet minimum performance standards on this SJT.

Keywords: situational judgement test, professionalism, professional attributes, affective, assessment

INTRODUCTION

Schools and colleges of pharmacy are required to teach and assess students pharmacists’ attributes in the affective domain, including professionalism.1,2 Knowledge can often be assessed by administering multiple-choice questions, using Bloom’s taxonomy as a framework to determine students’ depth of knowledge.3 Professionalism and other “soft skills” are more difficult to objectively assess in an efficient, valid, and reliable manner and should be classified using Krathwohl’s taxonomy.4 Examples of techniques used to assess students’ professional attributes include drafting personal statements, completing self-efficacy ratings, soliciting references from people they have worked closely with, participating in multiple mini interviews, and/or having their behavior directly observed over a period of time. Each of these assessment techniques has limitations, including low reliability and/or validity (eg, personal statement, self-efficacy ratings, references), or are logistically cumbersome or cost prohibitive (eg, multiple mini interviews, repeated direct observations, of behavior patterns).5-7

Situational judgement tests (SJTs) are a valid and reliable way to assess students’ attributes in the affective domain, such as professionalism and leadership.8,9 Situational judgement tests are written or videotaped scenario-based tests that assess judgements that the test taker would commonly have to make in a typical work environment. These tests are purported to measure prosocial implicit trait policies (ITP), which are beliefs that individuals develop about the effectiveness of certain behaviors in a given situation.8,10-13 This allows the test taker to rank, rate, or prioritize responses to a given situation. Faculty members understand that students knowing the most effective responses to scenarios does not mean they will actually respond in this manner when faced with similar scenarios in the real world. However, responses given by job applicants on an SJT have been shown to strongly predict job performance related to the attributes assessed.11 In principle, the test items on an SJT describe or depict scenarios commonly encountered in a profession and the response options include a variety of methods to address each problem.

There are three common types of items on an SJT: rating, ranking, and multiple choice.8 Items on an SJT can be scored in a variety of ways to reflect the type of question used and the variations in the appropriateness of the best approach to address the scenario. Because SJTs measure behavioral judgements, there is often not a definite “correct response.” Which responses are deemed appropriate will likely depend on the role and context in which a judgement is being made. Therefore, the appropriateness of each response should be confirmed with a group of subject matter experts.

Situational judgement tests allow for standardization of assessment related to professional attributes in the affective domain, as all students complete the assessment using standardized scenarios. This method is also logistically feasible as the administration process is similar to traditional knowledge-based examinations and does not require repeated direct observations of behaviors. Development of an SJT may be resource intensive as it requires faculty members to develop new skills in scenario and item writing that are unique compared to skills required for creating traditional knowledge-based examinations.

The primary purpose of this project was to develop, pilot, and validate an SJT to assess the educational outcome of professionalism in a Doctor of Pharmacy (PharmD) program. The secondary purpose was to assess test fairness by examining student performance based on gender, ethnicity, and campus location.

METHODS

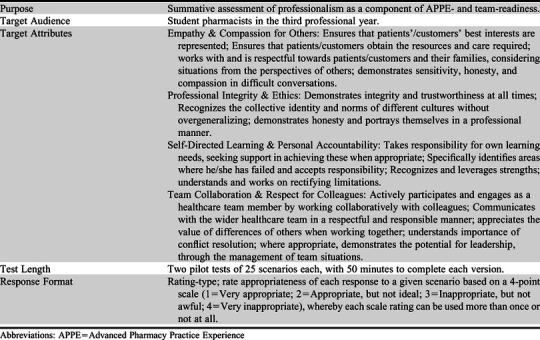

The development of this SJT began with creation of test specifications, including the selection and definition of target professional attributes assessed, the target audience, the purpose of including the SJT in the curriculum, test length and duration, and the types of questions to incorporate (Table 1). Factors that contributed to the identification of the target professionalism attributes used in this SJT included: current Doctor of Pharmacy (PharmD) program accreditation standards, review of the literature in health sciences education related to assessment of professionalism, and discussion regarding attributes that could be assessed using an SJT. The final list of attributes was determined via consensus building by the study authors.

Table 1.

Specifications for a Professionalism Situational Judgement Test Developed for Assessing Third-Year Pharmacy Students’ Readiness for Advanced Pharmacy Practice Experiences

After finalization of test specifications, 12 faculty subject matter experts participated in a two-day SJT scenario and item-writing workshop. These faculty members were selected to participate because they had worked in a variety of pharmacy practice settings (ambulatory care, community, health-system pharmacy, pharmaceutical sciences). Also, all 12 experts had experience teaching the PharmD curriculum at the University of Florida, which primarily uses collaborative learning methods within integrated courses.14 The workshop provided the faculty members with training in the key elements of writing scenarios and items for SJTs and served as a catalyst for them to begin writing scenarios to be used for a pilot SJT.

Working independently, the 12 faculty members created a total of 75 scenarios simulating common situations from classroom or pharmacy practice settings. Each scenario included five to eight responses and was written using a rating-type question format wherein test takers would be asked to rate the appropriateness of each of the possible responses to the scenario presented. Scenarios and the accompanying items were mapped to one of the target attributes of professionalism. Consultants experienced in development of SJTs and research then conducted a detailed review to determine the quality of the scenarios and responses. Scenarios and responses were reviewed with best practices of SJT design principles in mind, including ensuring scenarios measured one of the target professional attributes for pharmacy students, would be appropriate to ask all students, and did not include unnecessary clinical information. During this phase of the review process, scenarios and items were removed if they were specific to a process (eg, changing work schedule, reporting a medication error), did not require the test taker to make a significant judgement, asked the test take to make a knowledge-based judgement (eg, a clinical decision), or were too emotionally taxing. All scenarios and items were then reviewed by the subject matter experts for content validity, professional attribute measured by each scenario and response, and consensus of ratings for each response to be used as the answer key. Next, 50 scenarios were identified to include on this pilot SJT.

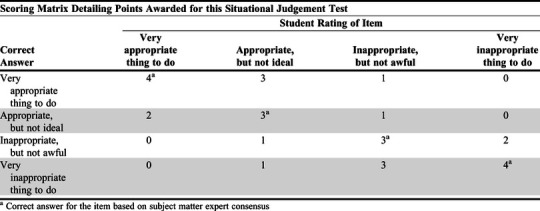

The 50 scenarios and associated responses were uploaded to the electronic testing program, Qualtrics (Provo, UT) and were reviewed to ensure consistency of visual representation and content. Items were scored using a matrix that was based on a near-miss system that allowed for partial credit to be given. Consultants experienced in the development of SJTs reviewed the pilot data along with the scenario content and the different ratings that had been assigned to each item throughout the development process to determine the final answer key for all items. Higher scores were given for student ratings of appropriateness which more closely aligned with the final answer key. An example of an SJT scenario with items is provided in Appendix 1. An example of an SJT scoring matrix is provided in Appendix 2.

A pilot study was then conducted to assess the reliability of the SJT. Student pharmacists in the third professional year (P3) served as the test population for the SJT pilot. The test population included student pharmacists from all three campus locations of the University of Florida College of Pharmacy. In the pilot, the SJT was divided into two versions, each containing 25 scenarios. Both test versions were administered online via Qualtrics in spring 2018 just prior to the start of advanced pharmacy practice experiences (APPEs). The P3 students completed the two versions of the test on different days, approximately 48 hours apart. Students were given 50 minutes to complete each version. Students also completed an evaluation questionnaire at the conclusion of version 2. The questionnaire included five items on a four-point Likert scale ranging from strongly agree to strongly disagree. This study was deemed exempt by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at the University of Florida.

Internal consistency was measured using Cronbach’s alpha. Items were removed that reduced Cronbach’s alpha by .005 or more to improve internal consistency of this SJT and to provide a more representative picture of future iterations of the test. These items were removed from the data prior to final psychometric analysis to evaluate the internal consistency, test difficulty, fairness, and face validity. Item quality was determined using the item discrimination index (DI), which is the correlation between the item and the overall mean SJT score (excluding the item itself). Items were classified in terms of their quality as good (DI>0.25), satisfactory (DI=0.24-0.17), moderate (DI=0.16-0.13), or limited (DI<0.13).12 Test difficulty was determined using mean scores, standard deviation, and score distribution. Test fairness related to gender, ethnicity, and campus was measured using an independent samples t test. Because of sample size, ethnicity was divided into two groups for this analysis, White students, and Black and minority ethnic (BAME) students, which includes those of non-white ethnicity, such as Hispanic. Students who did not report gender and ethnicity were not included in the analyses. One-way ANOVA was used to compare performance based on campus location. The Cohen d test was used to measure effect size for gender, ethnicity, and campus location.15 Face validity was measured using survey results, which were summarized using descriptive statistics.

RESULTS

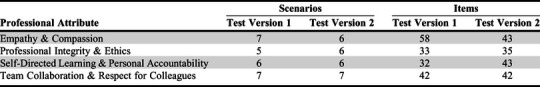

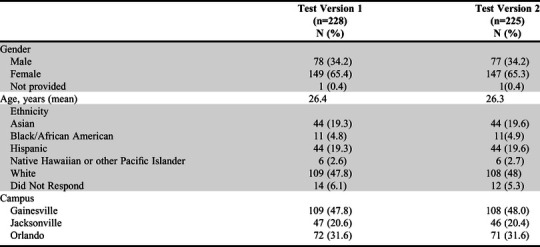

Fifty scenarios and 328 items were included in the pilot test: test version 1=165 items and test version 2=163 items. The distribution of scenarios and items across the four target professional attributes are outlined in Table 2. Test version 1 was completed by 228 students and test version 2 was completed by 225 students. Student demographics are summarized in Table 3.

Table 2.

Distribution of Scenarios and Items Based on Target Professional Attribute

Table 3.

Demographics of Participants in the Pilot Situational Judgement Test

On version 1 of the test, 144 (87%) of the 165 items performed well psychometrically (based on impact on Cronbach’s alpha) and were included in the final analysis. On version 2 of the test, 137 (84%) of the 163 items performed well psychometrically and were included in the final analysis. The distribution of item quality on version 1 of the test included 11 good items (8%), 46 satisfactory items (32%), 30 moderate items (21%), and 57 limited items (40%). The distribution of item quality on version 2 of the test included 20 good items (15%), 37 satisfactory items (27%), 22 moderate items (16%), and 58 limited items (42%). Both test versions demonstrated good reliability with regards to internal consistency (test version 1, α=0.77; test version 2, α=0.79).

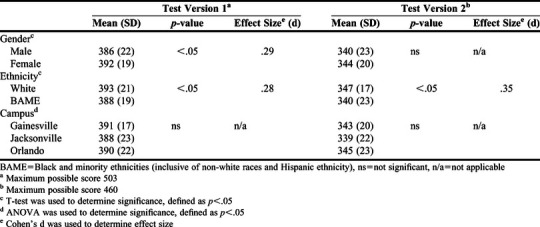

Students’ mean score on test version 1 was 77.6% (raw mean score 390, SD=20, range 318-429, maximum possible score 503) and the mean score on test version 2 was 74.5% (raw mean score 342, SD=21, range 263-387, maximum possible score 460). Measures of skewness indicated that the distribution of scores was moderately skewed (test version 1 skewness was -.84; test version 2 skewness was -.85). Kurtosis for test version 1 (.80) and test version 2 (.96) was within an acceptable range.16 Visual inspection of the distribution of scores also supported the assumption of normality.17 To examine the fairness of the tests, differences in performance within the student sample were analyzed for three demographic variables including gender, ethnicity, and campus (Table 4). Female students performed slightly better than male students on one version of the test. White students performed slightly better than BAME students on both versions of the test. No differences in performance were observed between students at the three campus locations.

Table 4.

Fairness Evaluation Related to Gender, Ethnicity, and Campus for Pilot Situational Judgement Test

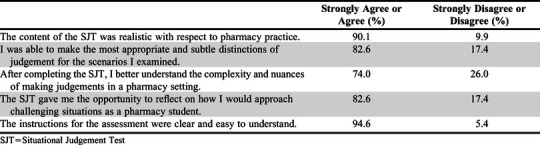

The response rate for the student evaluation questionnaire was 100%. Students were asked to indicate their level of agreement with items regarding the tests’ relevance, difficulty, clarity, and ability to differentiate responses (Table 5).

Table 5.

Student Perceptions Regarding the Situational Judgement Test

DISCUSSION

Situational judgement tests have been used primarily for employee selection processes, ie, to identify top-performing applicants who possess attributes that complement the knowledge and skills required in a particular profession.18-22 The application of the SJT as a high-stakes assessment in health professions education is starting to be explored. Goss and colleagues developed a high-stakes SJT to assess professionalism in final-year medical students in Australia.9 They developed three SJTs (40 scenarios per test) and administered them one month apart from each other to assess professionalism principles aligned with the five attributes used for the medical school selection process at the United Kingdom Foundation Programme.23 These attributes were coping with pressure, working effectively as part of a team, effective communication, problem solving, and commitment to professionalism.23 Using a combination of ranking and selection-type items, the reliability of that SJT was below typical standards (Cronbach’s alpha=0.45-0.63). They attributed this to the complexity of measuring professionalism and the use of multiple item types.

In contrast, our SJT focused on four professional attributes we identified as important for pharmacist practice, aligned with the programmatic educational outcome related to professionalism, and difficult to effectively assess using other approaches. Analysis of the pilot results indicate that psychometrically, our SJT is an effective test for assessing the targeted professional attributes for student pharmacists. Both pilot test versions had close to normal distribution and showed appropriate internal consistency. This demonstrates that both tests were capable of differentiating between students, thus providing a sufficient spread of scores. The level of difficulty is likely appropriate for an assessment, ie, the majority of students will perform at a satisfactory level, with a relatively high proportion of items within the test being identified as satisfactory or moderate in difficulty. This suggests that the SJT would be able to identify and differentiate between the poorest performing students, who may benefit from additional support prior to entering APPEs. The minimum desired level of reliability for a summative assessment is α=0.70.24 The Cronbach’s alpha for both SJT versions in this pilot (test version 1=0.77; test version 2=0.79) suggest that the scores are an accurate reflection of the test takers’ skills in relation to the domains being assessed and that the scoring approach used is appropriate for operational use to achieve the desired reliability. The measured reliability of our SJT was higher than that found by Goss and colleagues for their SJT, which may have been because of our use of a single item type and a narrower definition of professionalism attributes assessed on the SJT.

Wolcott and colleagues developed an SJT designed for administration in five minutes that focused on empathy as part of a capstone assessment for first professional year student pharmacists.25 Nineteen scenarios included on the SJT were written by a single author with the expectation that students would complete as many as possible in the five-minute limit. Students completed a mean of 9.5 scenarios (range, 5-16). For the items completed by at least 20 students, the reliability observed was within expected standards (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.73 and 0.75). The authors did not specify the types of questions included on the SJT. Reliability of our SJT was in alignment with the SJT created by Wolcott and colleagues, although our SJT assessed a greater number of attributes (four attributes vs one attribute; item range per attribute, 5-7 vs 19) and permitted more time to complete the test (50 minutes vs 5 minutes).

No differences were observed in student performance based on campus location, a result which was expected because admissions metrics and curricular experiences were equivalent across campuses. While differences in scores based on gender and ethnicity were found, the effect sizes were small and, for gender, inconsistent across test versions. In addition, the differences identified among test takers were consistent with those found among test takers of other SJTs used within health professions education.26,27 Based on these findings, differences between groups will continue to be monitored during future administrations of this SJT.

Feedback from students indicated they felt this SJT was a realistic test that should be included as part of the PharmD program. The findings provide good evidence that the test specifications (Table 1) were suitable for this context. Students perceived the SJT as an opportunity to gain exposure to challenging situations they may encounter as a pharmacy student. Because of this, an SJT may be useful to implement earlier in the program as a formative assessment to track development of professional attributes in students as they progress.

This SJT will be added to our current APPE readiness process, which includes assessment of student knowledge and skill, to provide a more robust evaluation. Future directions for SJT development include implementation of a standard-setting process, and the incorporation of a formative SJT in the first and second professional years of the program to provide earlier identification of students who do not meet the performance standards. Personalized learning plans could be created for students who perform below expected standards on the formative SJT. Scenarios for the formative SJT will align with the same professional attributes but the settings will be ones with which this group of students can better relate, such as the classroom and introductory pharmacy practice experiences.

CONCLUSION

We developed a reliable SJT to assess four professional attributes: empathy and compassion for others; professional integrity and ethics; self-directed learning and personal accountability; and team collaboration and respect for colleagues. While small differences were observed in performance of subgroups for both ethnicity and gender, these will be monitored in future use of this SJT and investigated further to explore the differences. Students indicated they felt this SJT was realistic and provided an opportunity to reflect on how to respond to challenging situations.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors wish to thank Lindsey Childs-Kean, Stacey Curtis, Lori Dupree, Heather Hardin, Cary Mobley, Priti Patel, Erin St. Onge and Lihui Yuan, who contributed to writing items for this SJT.

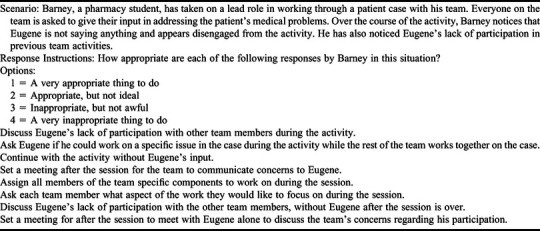

Appendix 1.

Example of a Scenario from a Situational Judgement Test

Appendix 2.

Example SJT Scoring Matrix

REFERENCES

- 1.Accreditation standards and key elements for the professional program in pharmacy leading to the doctor of pharmacy degree, 2016. Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education; Chicago, IL: https://www.acpe-accredit.org/pdf/Standards2016FINAL.pdf. Accessed June 19, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Medina MS, Plaza CM, Stowe CD, et al. Center for the Advancement of Pharmacy Education 2013 Educational Outcomes. Am J Pharm Educ. 2013;77(8):Article 162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bloom BS. ed. Taxonomy of Educational Objectives. The Classification of Educational Goals. Handbook I: Cognitive Domain. New York, NY: McKay; 1956. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anderson L, Krathwohl D, eds. A Taxonomy for Learning, Teaching, and Assessing: A Revision of Bloom’s Taxonomy of Educational Objectives. 1st ed. London, England: Longman; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Patterson F, Knight A, Dowell J, et al. How effective are selection methods in medical education and training? a systematic review. Med Educ. 2016;50(1):36-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kelley KA, Stanke LD, Rabi SM, et al. Cross-validation of an instrument for measuring professionalism behaviors. Am J Pharm Educ. 2011;75(9):Article 179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tanzer K, Dintzer M. Promoting professional socialization within the experiential curriculum: implementation of a high-stakes professionalism rubric. Am J Pharm Educ. 2017;81(1):Article 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patterson F, Zibarras L, Ashworth V. Situational judgement tests in medical education and training: research, theory and practice: AMEE Guide No. 100. Med Teach. 2016;38(1):3-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goss BD, Ryan AT, Waring J, et al. Beyond selection: the use of situational judgement tests in the teaching and assessment of professionalism. Acad Med. 2017;92(6):780-784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Motowidlo SJ, Hooper AC, Jackson HL. Implicit policies about relations between personality traits and behavioral effectiveness in situational judgement tests. J Appl Psychol. 2006;91(4):749-761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lievens F, Patterson F. The validity and incremental validity of knowledge tests, low-fidelity simulations, and high-fidelity simulations for predicting job performance in advanced-level high-stakes selection. J Appl Psychol. 2011;96(5):927-940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Patterson F, Driver R. Situational judgement tests. In Patterson F, Zibarras L, eds. Selection & Recruitment in the Healthcare Professions. London, England: Palgrave Macmillan; 2018:79-112. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Motowidlo SJ, Lievens F, Chosh K. Prosocial implicit trait policies underlie performance on different situational judgement tests with interpersonal content. Human Performance. 2018;31(4):238-254. [Google Scholar]

- 14.University of Florida College of Pharmacy Pharm.D. Curriculum. https://curriculum.pharmacy.ufl.edu/curriculum-courses/. Accessed June 19, 2020.

- 15.Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. New York, NY: Routledge Academic; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bulmer MG. Principles of Statistics. New York, NY: Dover Publications, Inc.; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cramer D, Howitt D. The SAGE Dictionary of Statistics. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 18.University Clinical Aptitude Test (UCAT). UCAT Consortium website. https://www.ucat.ac.uk/ucat/. Accessed June 19, 2020.

- 19.CASPer. Altus Assessments website. https://altusassessments.com/discover-casper/. Accessed June 19, 2020.

- 20.Dore KL, Reiter HI, Kreuger S, et al. CASPer, an online pre-interview screen for personal/professional characteristics: prediction of national licensure scores. Adv in Health Sci Educ. 2017;22(2):327-336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dore DL, Reiter HI, Eva KW. Extending the interview to all medical school candidates – computer-based multiple sample evaluation of noncognitive skills (CMSENS). Acad Med. 2009;84(10 Suppl):S9-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.General Pharmaceutical Council. Pharmacist Education and Training. https://www.pharmacyregulation.org/education/pharmacist-education. Accessed June 19, 2020.

- 23.Petty-Saphon K, Walker KA, Patterson F, et al. Situational judgement tests reliably measure professional attributes important for clinical practice. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2017;8:21-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cortina JM. What is coefficient alpha? an examination of theory and applications. J Appl Psychol. 1993;78(1):98. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wolcott MD, Lupton-Smith C, Cox WC, McLaughlin JE. A 5-minute situational judgement test to assess empathy in first-year student pharmacists. Am J Pharm Educ. 2019;83(6):Article 6960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Husbands A, Rodgerson MJ, Dowell J, Patterson F. Evaluating the validity of an integrity-based situational judgement test for medical school admissions. BMC Med Educ. 2015;15:144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Patterson F, Galbraith K, Flaxman C, Kirkpatrick CMJ. Evaluation of a situational judgement test to develop non-academic skills in pharmacy students. Am J Pharm Educ. 2019;84(10):Article 7074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]