Abstract

Objective. To characterize shared governance in US schools and colleges of pharmacy and recommend best practices to promote faculty engagement and satisfaction.

Findings. The literature review revealed only one study on governance in a pharmacy school and some data from an AACP Faculty Survey. Of the 926 faculty members who responded to the survey, the majority were satisfied or very satisfied with faculty governance (64%) and the level of input into faculty governance (63%) at their school. Faculty members in administrative positions and those at public institutions were more satisfied with governance. The forum resulted in the development of five themes: establish a clear vision of governance in all areas; ensure that faculty members are aware of their roles and responsibilities within the governance structure; ensure faculty members are able to join committees of interest; recognize and reward faculty contributions to governance; and involve all full-time faculty members in governance, regardless of their tenure status.

Summary. Establishing shared governance within a school or college of pharmacy impacts overall faculty satisfaction and potentially faculty retention.

Keywords: governance, faculty affairs, satisfaction, shared governance

INTRODUCTION

Shared governance is defined as “the shared responsibility between administration and faculty for primary decisions about the general means of advancing the general educational policy determined by the school's charter.”1 Over the past two decades, much attention has been focused on defining expectations and ideals for faculty involvement in shared governance in institutions of higher learning.1-4 Colleges and universities across the United States have diverse and often complex organizational governance structures, with great variability in the level of shared responsibility between administration and faculty members. Assignment of these responsibilities is greatly influenced by both internal and external factors,1,5 such as tenured vs non-tenured status, voting rights, areas of control and hiring decisions, curricular matters, tenure and promotion guidelines, and the extent to which shared governance between the faculty and administration is allowed.4

The Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE) requires that schools and colleges of pharmacy meet basic standards regarding school governance (standards 8.7), which ensures faculty participation in school or college governance.6 Yet, the standard is quite broad, only stating that “the college or school uses updated, published documents, such as bylaws, policies and procedures, to ensure faculty participation in the governance of the college or school.” The only primary literature related to shared governance in schools and colleges of pharmacy is focused on student governance.7 Thus, little is known about best and successful practices regarding shared governance models within pharmacy education.

To address this, the American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy’s (AACP’s) Council of Faculties charged the 2017-2018 Faculty Affairs Committee to conduct an environmental scan of the Academy. The scan was designed to explore faculty governance structures within colleges and schools of pharmacy, including the various classes of faculty members represented within those governance structures and their respective voting rights. The work that follows is the result of the committee’s efforts.

METHODS

Responding to its charge, the 2017-2018 Faculty Affairs Committee developed three strategies to identify current practices within pharmacy education and, based on best practices, to make recommendations for schools and colleges regarding faculty governance. The first was a thorough literature review of faculty governance within higher education; the second was to develop a survey to ask about the governance structure that faculty members have at their individual institutions and their satisfaction with it; and the third was to host an open forum at the February 2018 INspire (interim) meeting of AACP to gather additional thoughts, perspectives, and feedback regarding our charges and recommendations.

The literature search was conducted through EBSCO and included the following databases: Academic Search Premier, ERIC, Medline, and International Pharmaceutical Abstracts. The search was limited to English language scholarly and peer-reviewed journals over a 15-year period (2003-2018) and used the following terms: college/university governance, shared governance in higher education and health professions, and pharmacy. Publications from outside the United States, those describing clinical governance, or those unrelated to higher education were excluded.

After the completion of our literature review, a 27-item survey instrument was created to determine the status of faculty governance within US schools and colleges of pharmacy. The survey, which was administered through SurveyMonkey (Menlo Park, CA), was conducted by the committee to identify relevant, common, and best practices regarding faculty governance in health professions and higher education. In addition to committee members, the survey was shared with 10 additional faculty members at other institutions, as well as the administrative board of the COF, and feedback was incorporated for content and clarity. A link to the survey was distributed to the pharmacy academy via AACP Connect, direct emails via AACP E-lerts, and through direct contact with department chairs, deans, and other administrators, with the goal of reaching as many pharmacy faculty members as possible, regardless of AACP membership status.

Descriptive statistical analysis was performed on all completed responses. Response summaries were provided for survey questions, with missing responses excluded from the analysis. A descriptive summary of question responses was analyzed by tenure status (not eligible, tenure-track, and tenured faculty members). As determining faculty members’ satisfaction with governance was an integral part of the committee’s work, we also conducted exploratory regression analysis using Likert-scale responses to two questions pertaining to faculty satisfaction with school governance to attempt to identify groups of faculty members whose satisfaction with governance was significantly different from others. A simplified single-factor model for the latent variable governance satisfaction was created with these two items: “How satisfied are you with your college/school’s governance structure?” and “Are you satisfied with the level of faculty input into your college/school’s governance?”8 Question responses were scored as follows: one point for “very dissatisfied” through five points for “very satisfied” and a governance satisfaction score was created as a sum of these two question responses. For example, a faculty member responding “satisfied” for both questions would yield a score of eight (four points for each question) out of a maximum possible score of 10 points. Governance satisfaction was divided at a score of ≥8, which equated to minimal satisfaction for both questions (or, rarely, very satisfied for one and neutral on the other question). Those who were satisfied with governance were considered to have a high governance satisfaction and those below eight did not. The distribution of GS scores was used to determine break points for analysis using the GS score as the dependent variable adjusting for demographic variables as model covariates. A stepwise logistic regression approach was used to determine which variables would remain in the final model, with a significance level for variable entry set conservatively to 0.3.9,10 Model lack of fit was evaluated by the Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test.9 Survey results were collected in SurveyMonkey (San Mateo, CA), and all analyses were completed using SAS, version 9.4 (Cary, NC).

This initial survey results were used as a discussion topic when members of the committee hosted a forum at the 2018 AACP INSpire meeting. The 25:10 Crowd Sourcing technique (www.liberatingstructures.com) was used to identify the five most important themes related to governance in order of highest priority.

FINDINGS

The literature review revealed that the most comprehensive compilation of the major obstacles to and recommendations for the inclusion of all faculty members in shared governance processes was published by the American Association of University Professors (AAUP) in 2013.11 Through this work, the AAUP identified five overarching principles, which they then used as the foundation for the specific recommendations in their report and which can also be used by individual institutions when addressing their specific concerns related to governance. First, the AAUP affirmed that the definition of faculty needs to be clear and should include more than just those with tenured or tenure-track appointments. Second, despite recognized challenges in its implementation, the second principle was that all faculty members should have the opportunity to participate in governance. Faculty members must be knowledgeable about and take advantage of the opportunities to participate fully in shared governance in order for its benefits to be realized. They affirm that academic freedom and participation in governance are closely interrelated and, finally, all faculty, regardless of appointment, should receive due-process protections in order to support academic freedom.

A review of the literature revealed that faculty governance issues seem to affect all types of institutions, commonly in historically Black colleges and universities12 and liberal arts colleges,13 while limited data exist for health professions schools. One study describing the significant governance issues that exist in dental schools increased awareness of the unique operating structure of dental schools, and made specific recommendations on how governance, management, and leadership could be adapted to enhance governance effectiveness.14

We found that little data specific to shared governance in schools and colleges of pharmacy existed, aside from a study exploring student governance.7 However, findings from the annual AACP Faculty Survey, in which assessment of faculty satisfaction with administration and governance is a primary objective, suggest that most pharmacy faculty members are satisfied with the functioning of existing administration and governance structures.15 For example, in the 2017 survey, 87.3% of the faculty members who responded either agreed or strongly agreed that their school or college provided opportunities for faculty participation in governance.15

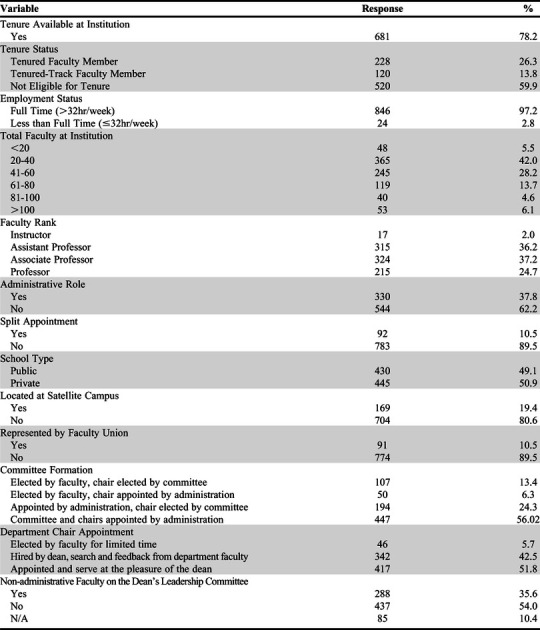

The committee received a total of 929 responses regarding the survey we conducted, with 926 faculty members consenting to complete the survey instrument, and three declining to participate. Of those who did participate, any questions that a respondent skipped were excluded from this analysis. Faculty members differed based on tenure status, rank, administrative appointments, relative size of their school or college’s faculty, whether they were employed at a public or private institution, if they were part of a faculty union, and whether they primarily resided on the main or a satellite campus. The complete demographic data for respondents is displayed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographics of Faculty Members at US Schools and Colleges of Pharmacy Who Responded to a Survey on Governance Within Their Institution

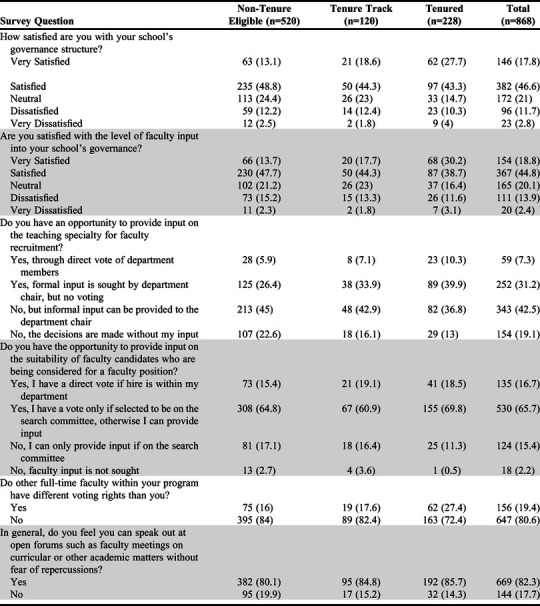

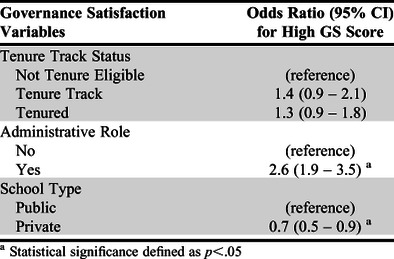

The majority of faculty members reported being either satisfied or very satisfied with their school governance structure (64%) and level of input on school governance (63%). Because of the charge given to our committee, we had a high interest in the level of faculty satisfaction with and input into governance structure and any significant differences in responses between groups of faculty members. For example, the majority of respondents reported being satisfied or very satisfied with their school governance structure (64%) and satisfied or very satisfied with the level of faculty input on school governance (63%). However, the percentages dropped to 57% and 55%, respectively, when faculty members with an administrative title were excluded. To determine this, we explored regression analysis using the responses of two Likert-style questions pertaining to faculty satisfaction with school governance as described in the methods. With this approach, we developed a final model of governance satisfaction that found significant differences based on whether a faculty member had an administrative role or was at a public or private institution (Tables 2 and 3). With the full model, faculty members reporting administrative roles were two and a half times more likely to have a high governance satisfaction score (Table 3). Additionally, faculty members working at public institutions were significantly more likely to have a high governance satisfaction score when compared to faculty members at private institutions (Table 3). There was no significant difference between tenure track status and governance satisfaction once adjusted for covariates. There was no evidence of lack of fit with the Hosmer and Lemeshow test (p=.11) for the final adjusted model.

Table 2.

Survey Responses of Faculty Members at US Schools and Colleges of Pharmacy Regarding Governance Within Their Institution, No. (%)

Table 3.

Governance Variables Significantly Associated With Governance Satisfaction Scores of Faculty Members at US Schools and Colleges of Pharmacy (n=815)

As a great deal of shared governance is accomplished through committee work and committee appointments, committee structure and formation were another major focus of our study. The majority of respondents (56%) indicated that committees, along with the committee chair, were generally appointed by the administration. Almost one in four respondents (24%) indicated that school administration appointed the committee and its members but the chair was elected by the committee members, while only 13% of respondents reported that committee members and the committee chair were selected by the faculty. Generally, faculty were able to serve on a committee, regardless of rank, with the exception of promotion and tenure committee, as 76% of respondents had no restrictions, while only 13% had restrictions (11% did not know.)

In terms of faculty members’ ability to change the governance structure, 68% of respondents indicated their school had a mechanism in place for this, 8% said their school did not, and 24% were unsure. The majority of respondents said faculty members had a voice in matters pertaining to student admissions and admission policies (81%), curricular matters (92%), student progression policies (82%), and promotion policies (68%). A significant number of faculty members seemed to be unfamiliar with their rights and responsibilities within their program’s shared governance model. Some respondents did not know if they had direct voting rights or another means of faculty representation in decision making related to student admission policies (6%), student progression policies (7%), or matters pertaining to faculty promotion policies (13%). Finally, over half of the respondents were unaware of whether they were permitted to participate in a vote of no confidence in an administrator.

The recruitment of faculty members and opportunity to provide input into the teaching specialty or research focus of an open position was another area of shared governance that was explored in the survey. Only 19% of the faculty members responding felt that the opportunity to provide input into the focus area of an open position did not exist; however, the level of input varied greatly. Informal input that could be provided to the department chair was the most commonly cited by respondents, (43%), while another 31% responded that formal input was sought by the department chair. A vote by the department was the least common method used (reported by 7% of respondents). Once the faculty area is selected, the level of input that faculty members had in which candidate to hire also varied. The majority of respondents indicated that input was requested, either through a direct vote if the faculty candidate was to be part of their department (17%) or through input provided to the search committee (66%). Only 15% of respondents felt the search committee did not consider their input, and only 2% felt that faculty input was not sought.

The situation at most schools is apparently a little different when the faculty member to be hired is a department chair as the majority of respondents (52%) indicated that their department chairs were appointed by the dean, while only 6% were elected by the faculty. The remaining 42% were hired after a thorough search which included feedback from the department faculty. Finally, we explored whether faculty members felt free to speak at faculty meetings regarding academic matters without fear of repercussions, and all three faculty appointments (more than 80% of respondents) reported that they were comfortable speaking out. Approximately 20% of faculty members stated that they did not feel comfortable to speak freely at faculty meetings regarding academic matters without fear of repercussions. Interestingly, tenure status did not play a significant role in a faculty member’s comfort as tenure-track or tenured faculty were almost as likely to feel uncomfortable speaking up as their non-tenure eligible counterparts.

The preliminary survey results were used as an impetus to further open the dialogue among faculty members about faculty governance. At the 2018 INspire meeting, participants in the COF Forum were asked to provide feedback on the most significant governance issues affecting the faculty members at their institutions. Through use of the 25:10 Crowd Sourcing technique, the following five themes were identified in order of highest priority. First, faculty members’ workload was identified as a significant barrier to participation in shared governance. Participants were asked whether workload, including participation in governance as a form of service, was being appropriately and comprehensively measured and taken into consideration by administration in general, specifically during the promotion and tenure process. Second, participants were asked whether faculty members had sufficient time to commit to effective participation in the governance process, particularly when compared to the significance of their teaching and scholarship responsibilities.

This ties into the second ranked theme which was a concern regarding perceived inadequacy of faculty participation in shared governance overall. Participants raised concerns about unclear faculty expectations and understanding of their role in governance, the potential for differing expectations for participation between faculty members and administration, and breakdowns in communication between upper administration and faculty members related to institutional initiatives. Additionally, concerns were raised about a lack of accountability to ensure good faculty citizenship or participation in governance, which was the focus of another recent report of a separate COF Faculty Affairs Committee.16

The third theme centered around the promotion and tenure process itself with potential barriers being a lack of transparency in the policies and procedures guiding promotion and tenure. The fourth theme that emerged was the presence of differing rights and responsibilities for shared governance that are assigned to tenure track versus non-tenure eligible and/or adjunct faculty at some institutions. There may be differences in voting rights between tenured, tenure-track, and non-tenure eligible faculty members that may limit the ability of certain types or classes of faculty members to participate fully in shared governance, consistent with the findings of the survey. Additionally, some institutions limit the ability of non-tenure eligible faculty members to participate on university-level committees or to hold seats in the faculty senate. Some institutions may also limit the ability of non-tenure eligible faculty to participate in college-level committees and governance. Perceived inequality may in itself dissuade some faculty members from engaging in the work of governing their college of school.

The final theme that was identified involved concerns about the general decision-making process within schools and colleges of pharmacy. Specifically, there may be uncertainty or a lack of understanding of policies regarding the types of decisions that are made by administration with or without faculty input and the incomplete communication of decisions and the decision-making process back to faculty members. In summary, the five themes identified by pharmacy faculty members who participated in this forum, were very consistent with governance issues being raised by faculty across the country.12-14 They are also consistent with the findings of our governance survey.

DISCUSSION

Shared governance is a key factor impacting overall faculty satisfaction, with components of governance potentially impacting faculty retention.17,18 Given the limited research available in this area, an important goal of this project was to begin the process of collecting information on faculty satisfaction with institutional governance across schools and colleges of pharmacy. The search of the literature determined that shared governance is an area that colleges and universities struggle with throughout higher education.12-14 One especially relevant article explored the leadership, governance, and management in dental education, which identified many of the same issues that are faced in pharmacy education and helped the committee frame the survey questions to gather the most pertinent information.

This survey included 926 respondents from 141 public and private institutions. Our findings indicate that many faculty members not only have the opportunity to be involved, but have a voice in governance. The importance of faculty input into academic decisions is critical, specifically when discussing key areas affecting institutions, such as curricular changes, admissions criteria, and the promotion and tenure process. Despite these positive numbers, the survey suggests there is still an opportunity and need for improvement. Approximately 15% of respondents to the survey indicated they were dissatisfied or very dissatisfied with the faculty governance at their institution and the level of faculty input into governance. In comparison, the AACP 2017 survey reported 10% of respondents disagreed or strongly disagreed that there are opportunities for faculty participation in governance.15 Among dissatisfied respondents, 30% are at institutions that do not offer tenure. The availability of tenure at institutions may be a variable impacting satisfaction based on job stability. Additional variables associated with results indicating higher faculty satisfaction with governance include: those who are tenured, those with an administrative role, and those at public institutions. Faculty members with administrative roles and those at a public institution were more likely to be highly satisfied, potentially confounding the relationship between tenure status and governance satisfaction.

Limitations to this study include that the survey respondents may be biased towards individuals who are associated with AACP in some manner, as non-members would have been less likely to have receive contact about the survey since AACP communications were a main method of survey distribution. In an effort to mitigate this possibility, survey respondent’s demographics were compared with those received by the AACP Faculty survey in 2017-2018.15 The AACP faculty survey represented 98 institutions and had 3077 respondents in comparison to this study’s 141 institutions and 929 respondents. The number of faculty at a tenure granting institution (78% vs 80%) and tenured faculty members who responded (28% vs 26%) was consistent between the two studies. However, only 62% of survey respondents did not have an administrative title in comparison to 74% of the AACP faculty survey.15 Thus, administrators could have been over represented in our analysis. When this variable was accounted for, we found that administrators were generally more satisfied with GS than non-administrators. However, given the governance satisfaction variable is exploratory and unvalidated, additional sensitivity analysis would need to be conducted to validate the use of GS as a dependent variable. Finally, for individuals who were not satisfied with governance structures, this survey did not specifically address turnover intention or productivity. For instance, a faculty member who was not fully satisfied with the amount of input they had in hiring new faculty members or administrators may have had flexibility in their job, increased annual/sick leave, or an improved retirement package that made up for this.

Several governance considerations, such as the level of faculty participation in governance, the perceived role or value of a tenured, tenure track, or non-tenure track faculty member, and the opportunity for faculty members to comment on administrative decisions, warrant additional review beyond this study. The survey findings indicate the need for additional research to further define the possible factors contributing to faculty satisfaction and to enable the development of targeted resources to assist institutions in addressing variables. Obviously, private institutions are not likely to switch to become public institutions, so that is not modifiable. However, the employment status of the faculty members, the governance model used, and perceptions about job security may be areas to target for adjustment.

Three governance themes arose from the survey and could serve as discussion points for institutions to use in initiating a dialogue to address institution specific concerns. First, define the role of governance at your institution and the decision-making process on key academic areas (eg, curriculum, admissions, and academic standards). Second, define the role of faculty members and administration in governance and reinforce the importance of all faculty members being involved (ie, non-tenure track, tenure track, and adjunct faculty). Finally, account for and reward faculty contributions to governance through the promotion and tenure process. Schools may consider involving all of their faculty members or appointing a governance task force to facilitate discussion of these three themes to create or update their institutional governing model. In addition, as with any change, the importance of ongoing assessment of the structure will be integral given an ever-evolving academic climate.

Administrators and faculty members should be effectively represented in the governance of the university in accordance with its policies and procedures. In addition, the college or school should use updated, published documents such as bylaws, policies, and procedures, to ensure faculty participation in the governance of the college or school. The importance of all faculty members having a role in governance may offer a benefit in the overall advancement of pharmacy education by ensuring all stakeholders have a voice and a process to offer input on university policies and processes within a university governance model. In addition, the role of faculty members in governance is echoed through the AAUP’s recommendations as well as those of the Association of Governing Boards (AGB). Institutions are encouraged to ensure that voting within institutional governance is the same for all faculty members and the role of faculty members in decision-making is clearly defined.1,11 A shared governance model, as supported within AGB’s white paper, may provide the optimal, collaborative environment to ensure faculty and administrative input into key academic areas and to reinforce the importance of contributions from the campus community to institutional governance.

Recommendations

To optimize faculty governance and increase faculty satisfaction and participation in governance, the AACP Council of Faculties Faculty Affairs Committee of 2017-2018 makes the following recommendations to academic pharmacy stakeholders, ie, pharmacy faculty members, schools and colleges or pharmacy, and the AACP.

For all schools and colleges of pharmacy we have five recommendations. First, establish and/or maintain a clear vision of governance in all areas, including curriculum, admission, student progression, faculty promotion, and hiring policies. Second, ensure that faculty members are aware of their roles and responsibilities within their governance structure by including this information as part of new employee orientation programs and ensure the information is regularly reviewed with faculty members throughout their careers. Third, because faculty representation and voice often occur through committee structures, faculty members should have a means of joining committees of interest and chairing those committees as appropriate. Fourth, faculty contribution to governance should be accounted for and rewarded through the promotion and tenure process. Finally, faculty members should be defined in an inclusive manner, and all full-time faculty members should have an opportunity to be involved in governance, regardless of tenure status.

To AACP and the Council of Faculties, we proposed the following resolutions to the 2018-2019 Rules and Resolutions Committee of the COF. First that “AACP supports giving all faculty, regardless of tenure status or eligibility for tenure, decision-making and voting privileges in the governance structure of its schools or colleges.” Second that “AACP supports the inclusion of all faculty in decision making of processes within curriculum, admission, student progression, as well as faculty promotion and hiring policies.” Finally, that “The council of faculties encourages faculty to play an active role in their college/schools governance structure”

SUMMARY

The AACP Council of Faculties Faculty Affairs Committee explored the current status of faculty governance within US schools and colleges of pharmacy and developed recommendations for stakeholders to consider. Using a survey to assess government style and governance satisfaction, we found that faculty members at public institutions and faculty members with administrative titles were more likely than their counterparts to be satisfied with the faculty governance at their institutions. Overall, faculty members were generally satisfied with their involvement in governance, but the committee noted areas for additional review by institutions. Faculty members need to be aware of their roles within the governance structure and all faculty members should have an opportunity to participate in governance, be vocal, and have their roles recognized through the promotion process within their institutions. Pharmacy education is not alone in facing governance challenges, and many of our committee’s recommendations have been echoed by other organizations including dental education and liberal arts programs.13,14

Appendix 1. Survey Instrument

Does your institution offer tenure (yes, no)?

Which of the following best describes your status at your institution?

Non tenure eligible

Tenure track faculty member

Tenured faculty member

What is your current employment status?

Part time <20 hours a week

Part time 21-32 hours week

Full time – 32 hours+

What is the approximate size of the full-time faculty within the pharmacy program?

What is your faculty rank?

Do you have an administrative role within the pharmacy program (yes, no)?

Do you have a split appointment (part of your salary is paid by a hospital or other entity)?

What is the name of your pharmacy program?

Is your program a public or private institution?

Are you located on a satellite or extension campus or otherwise separated from the main campus?

Are you represented by a faculty union or have an AAUP negotiated contract?

How satisfied are you with your college/school’s governance structure?

Are you satisfied with the level of faculty input into your college/school’s governance?

Which of the following best describes how committees are formed in your college/school’s governance structure?

Committees are appointed by the administration, but the chair is elected by the committee

Committees are elected by the faculty and elect their chairs

Committees and committee chairs are appointed by the administration

Committee members are elected by the faculty, but the Chair is appointed by the administration

Except for your college/school’s tenure/promotion committee, does your faculty status limit your eligibility to serve on other committees in your college/school (yes - explain, no, I don’t know)?

Does your faculty status limit your eligibility to serve on any committees at your university (yes - explain, no, I don’t know)?

Do faculty have the means to initiate a change to your faculty governance structure and/or documents such as the faculty handbook (yes - explain, no, I don’t know)?

Do you have voting rights on matters pertaining to the following (yes – through a direct vote, yes – through faculty representation on the responsible committee, I don’t know, no)?

Admissions and admissions policies

Curriculum and what courses are approved

Student progression policies

Promotion policies

Can you provide input regarding the teaching specialty or research focus of new faculty that will be recruited?

Yes, through direct vote of department members

Yes, formal input is sought by the department chair, but no voting

No, but some level of informal input can be provided to department chair

No, the decisions are made without my input

Can you provide input on the suitability of faculty candidates who are being considered for a faculty position?

Yes, a direct vote if hire is within my department

Yes, I have a vote only if selected to be on the search committee, otherwise I can provide input

No, I can only provide input if on the search committee

No, faculty input is not sought

How are department/division chairs appointed?

They are elected by the faculty to a term of X years

They are appointed by the dean or upper administration

They are appointed by the dean after a thorough search and feedback from department faculty

Do you have voting rights in no confidence votes of the following (yes, no, I don’t know):

Department chair of your department

Dean of the college/school

Provost, president or other upper administration

Assistant/associate deans

Do other full-time faculty within your program have different voting rights than you do (yes - explain, no, I don’t know)?

Are there any non-administrative faculty that represent the faculty on the dean’s leadership committee (yes - explain, no, n/a)?

In general, do you feel you can speak out at open forums such as faculty meetings on curricular or other academic matters without fear of repercussions?

REFERENCES

- 1.Association of Governing Boards. Consequential Boards: Adding Value Where It Matters Most. Report of the National Commission on College and University Board Governance 2014. http://agb.org/sites/default/files/legacy/2014_AGB_National_Commission.pdf. Accessed July 1, 2020.

- 2.Cramer SF. Shared Governance in Higher Education, Demands, Transitions and Transformations. Vol 1 Albany, NY: State University of New York Press; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lechuga VM. Exploring current issues on shared governance. New Directions for Higher Education. 2004;2004(127):95-98. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Simplicio JSC. Shared governance: an analysis of power on the modern university campus from the presceptice of an administrator. Education. 2006;126(4):763-768. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maguad BA. Managing the system of higher education: competition or collaboration? Education. 2018;138(3):229-238. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education. Guidance for the Accreditation Standards and Key Elements for the Professional Program in Pharmacy Leading to the Doctor of Pharmacy Degree ("Guidance for Standards 2016. "). Published February 2015. https://www.acpe-accredit.org/pdf/GuidanceforStandards2016FINAL.pdfAccessed July 1, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kennedy DR, Ginsburg DB, Harnois NJ, Spooner JJ. The role and responsibilities of pharmacy student government associations in pharmacy programs. Am J Pharm Educ. 2015;79(7):100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.deVellis R. Scale Development: Theory and Applications. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Inc; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hosmer DW LS, Sturdivant RX. Applied Logistic Regression. 3rd ed: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shtatland EC, Barton MB. The perils of stepwise logistic regression and how to escape them using information criteria and the output delivery system. Proceedings of the Twenty-sixth Annual SAS Users Group International Conference. 2001:222-226. [Google Scholar]

- 11.American Association of University Professors. The Inclusion in Governance of Faculty Members Holding Contingent Appointments. AAUP Committee on Contingency and the Profession, Committee on College and University Governance; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fink JL., III In reply - Use of laptops and other technology in the classroom. Am J Pharm Educ. 2010;74(8):152c. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shinn LD. Top down or bottom up? leadership and shared governance on campus. Change: The Magazine of Higher Learning. 2014;46(4):52-55. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Townsend GT, Skinner R, Bissell V, et al. . Leadership, governance and management in dental education – new societal challenges. Eur J Dent Edu. 2008;12(s1):131-148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy 2017 https://www.aacp.org/sites/default/files/2017-10/2017_Faculty%20Survey_National%20Summary%20Report.pdf National Faculty Survey. 2017.

- 16.Hammer DP, Bynum LA, Carter J, et al. . Revisiting faculty citizenship. Am J Pharm Educ. 2019;83(4):7378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Coyle YM, Aday LA, Battles JB, Hynan LS. Measuring and predicting academic generalists' work satisfaction: implications for retaining faculty. Acad Med. 1999;74(9):1021-1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lowenstein SR, Fernandez G, Crane LA. Medical school faculty discontent: prevalence and predictors of intent to leave academic careers. BMC Med Educ. 2007;7:37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]