Abstract

Objective

Early during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) pandemic, Australian EDs experienced an unprecedented surge in patients seeking screening. Understanding what proportion of these patients require testing and who can be safely screened in community‐based models of care is critical for workforce and infrastructure planning across the healthcare system, as well as public messaging campaigns.

Methods

In this cross‐sectional survey, we screened patients presenting to a COVID‐19 screening clinic in a tertiary ED. We assessed the proportion of patients who met testing criteria; self‐reported symptom severity; reasons why they came to the ED for screening and views on community‐based care.

Results

We include findings from 1846 patients. Most patients (55.3%) did not meet contemporaneous criteria for testing and most (57.6%) had mild or no (13.4%) symptoms. The main reason for coming to the ED was being referred by a telephone health service (31.3%) and 136 (7.4%) said they tried to contact their general practitioner but could not get an appointment. Only 47 (2.6%) said they thought the disease was too specialised for their general practitioner to manage.

Conclusions

While capacity building in acute care facilities is an important part of pandemic planning, it is also important that patients not needing hospital level of care can be assessed and treated elsewhere. We have identified a significant proportion of people at this early stage in the pandemic who have sought healthcare at hospital but who might have been assisted in the community had services been available and public health messaging structured to guide them there.

Keywords: coronavirus disease 2019, epidemic, outbreak, pandemic, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

Many patients who present to EDs for COVID‐19 screening can be safely screened in community‐based settings.

Key findings.

Many patients who request screening for COVID‐19 in EDs can be safely managed in community settings.

Community‐based testing should be strengthened.

Public messaging campaigns should reiterate that community testing is a safe and appropriate model of care for those who are well.

Introduction

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) pandemic, caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV‐2) infection 1 , 2 , 3 has raised many challenges for the Australian healthcare system. EDs are viewed as one key provider for testing 4 , 5 and some departments have reported a significant increase in patients presenting for screening and testing for SARS‐CoV‐2. What is poorly understood is what proportion of patients presenting require SARS‐CoV‐2 testing, and for those who do, whether EDs represented the most appropriate location and resource allocation for this care.

A high number of presentations from patients for whom testing is not indicated (such as during the early phase of importation of the virus into the country, where a targeted testing approach was adopted) places additional strain on the public health service in terms of human resource allocation and use of limited stocks of personal protective equipment, and risks nosocomial transmission if these patients are mixed with patients with COVID‐19. For patients who do require screening, EDs do not provide the most appropriate setting for care for patients with no or mild symptoms.

If Australia does experience a substantial surge of SARS‐CoV‐2 infections, there will be significant strain on the healthcare system and it will become critically important that the right patient is assessed, and then, if necessary, treated at the right facility.

We must rapidly generate evidence to calibrate and direct policy for safe, effective and efficient models of care for COVID‐19. We do not know how many mildly unwell patients elect to present to an ED for screening and the barriers and facilitators to other models of care such as community‐based care.

Here, we provide the first characterisation of patients presenting to hospital‐based screening early during the outbreak with respect to their need for testing, perceived severity of illness and perceptions on alternative models of care.

Methods

Setting

The Royal Melbourne Hospital (RMH) is a metropolitan tertiary hospital service, with an ED that manages 80 000 patients per year. Co‐located with this ED, a SARS‐CoV‐2 screening clinic was established on 25 January 2020 to deal with the surge in patients presenting for screening. The model of care is described elsewhere. 6 In summary, patients self‐selected for either screening clinic or ED triage based on signage outside both locations. A smartphone app provided decision support for the patients as well as self‐registration. Screening clinic patients were registered and triaged on entrance to the clinic and any that required critical care were moved immediately to the ED resuscitation space. Operation of the screening clinic fell to the ED at our health service, as the only established provider of unscheduled care in the hospital.

Design and participants

A consecutive sample of patients presenting to the SARS‐CoV‐2 screening clinic from 18 March 2020 to 30 March 2020 were invited to complete a brief survey as part of their clinic registration process. Patients were included if they were aged 16 years or older, able to complete the self‐registration survey independently, or communicate to a staff member who could complete it on their behalf. Patients were excluded if they required urgent medical treatment (as assessed by triage staff) because they were re‐streamed from the screening area into the resuscitation space of the ED.

Patients completed the study‐designed survey embedded into a larger epidemiological and clinical triage system (described elsewhere) 6 upon registering at the clinic. The web‐based (REDCap) survey was completed either on their phone or on a hospital supplied tablet. When required, patients were assisted by triage staff to help them complete the survey, including assisting with language translation. Survey questions are outlined in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Health access preference questions for patients presenting for screening

| Question | n = 1846, n (%) |

|---|---|

| Why have you attended today?† | |

| A health telephone service referred me | 578 (31.3) |

| I decided independently to attend | 570 (30.9) |

| My GP referred me | 344 (18.6) |

| My employer requires me to be tested | 220 (11.9) |

| A friend or family member suggested it | 204 (11.1) |

| Another health professional referred me | 162 (8.8) |

| How severe do you think your illness is? | |

| Mild | 1025 (57.6) |

| Moderate | 449 (25.2) |

| Severe | 67 (3.8) |

| I have no symptoms | 239 (13.4) |

| Where have you been to find out information about COVID‐19?† | |

| Government website | 1262 (68.4) |

| Internet | 946 (51.3) |

| Social media | 564 (30.6) |

| Newspaper | 344 (18.6) |

| Listen to radio | 336 (18.2) |

| If you knew you did not have COVID‐19 today, would you still present to hospital for these symptoms? | |

| No | 1271 (70.9) |

| In regard to using GPs for screening…† | |

| I do not have a GP | 293 (15.9) |

| My GP cannot screen me for COVID‐19 | 287 (15.6) |

| I tried to contact them, but could not get an appointment | 136 (7.4) |

| This illness is too specialised for my GP | 47 (2.6) |

| I was concerned about the cost of going to the GP | 22 (1.2) |

| I am too sick to be managed by a GP | 12 (0.7) |

Can select more than one answer.

COVID‐19, coronavirus disease 2019.

Data were stored on REDCap via the hospital's server in accordance with relevant information security protocols. This quality assurance project (QA202025 RMH Ethics) was approved by Melbourne Health (5 March 2020).

Data cleaning and analysis

Data was cleaned and analysed using stata (version 15.0; College Station, TX, USA). Survey responses completed for children (i.e. age under 16 years) were excluded from analyses (n = 3). Date of birth and age was excluded from analyses if the response was impossible (e.g. age of 1000 years). It was assumed that the date of birth was simply input incorrectly at the time of data collection and, accordingly, all other data from those surveys was included in the analysis.

Descriptive data are summarised with median and interquartile range for skewed data while categorical data are described with overall frequency and proportions. Where analysis refers to the suspected case definition, this refers to the prevailing Victorian Department of Health and Human Services case definition for COVID‐19 7 at the time of patient presentation.

Results

A total of 2359 patients arrived at the RMH and requested screening for COVID of whom 1846 (78.3%) completed the survey. Most were female (51.3%), with a median age of 32 years (interquartile range 25.5–42.9 years).

Risk of COVID‐19

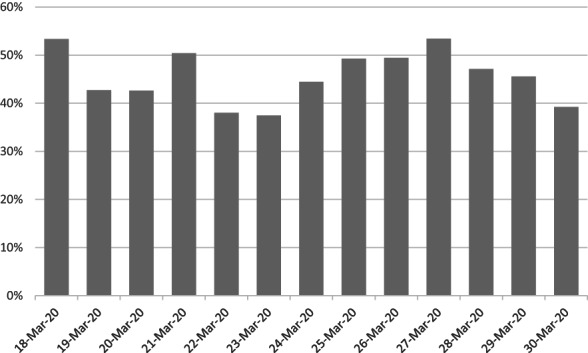

Whether a patient required testing depended on their symptoms, along with their travel history, contact with a confirmed case and whether they belonged to a high‐risk group (variably defined because of changing case definitions) (Table 1). Of our cohort, 825 (44.7%) of the 1846 patients met criteria for testing. The proportion of patients each day who met the criteria for COVID‐19 testing did not differ greatly or show any discernible pattern over time (Fig. 1).

TABLE 1.

Epidemiological risk factors† of survey population

| Characteristic | n = 1846, n (%) |

|---|---|

| Overseas travel within last month | |

| Yes | 519 (28.1) |

| No | 1316 (71.3) |

| Did not answer | 11 (0.6) |

| Of those who had travelled overseas, destinations included | |

| Mainland China‡ | 10 (0.5) |

| Iran | 1 (0.05) |

| Italy | 17 (0.9) |

| South Korea | 1 (0.05) |

| Singapore | 49 (2.7) |

| Belonging to a high‐risk group§ | |

| Healthcare worker | 358 (19.4% of n = 1846§) |

| Aged care worker | 29 (2.5% of n = 1146§) |

| Resident of aged or residential care | 11 (1.1% of n = 1047§) |

| Aboriginal Torres Strait Islander | 18 (1.3% of n = 1408§) |

| None | 759 (72.5% of n = 1047§) |

| Contact (casual or close) with a confirmed case? | |

| Yes | 311 (16.8) |

Please note, in the survey these risks were more broadly defined than in the case definition, aimed at alerting clinicians who could then further assess risk.

Excluding Macau, Hong Kong and Taiwan.

The case definition changed during the period of assessment with updates to whom was considered a high risk population. Therefore, the survey was updated during the study period.

Figure 1.

Proportion of patients over time who met criteria for the coronavirus disease 2019 testing.

Self‐assessed severity of illness

Most patients (n = 1025; 57.6%) rated their illness as only mild, with another 239 (13.4%) stating they had no symptoms at all (Table 2). A minority of presenting patients self‐reported moderate (n = 449; 25.2%) or severe (n = 67; 3.8%) symptoms. The majority (n = 1271; 70.9%) of patients would not have presented to hospital for their symptoms if they knew they did not have COVID‐19.

Healthcare access preferences

When asked about utilising other models of care for screening for COVID‐19, some patients (n = 287; 15.6%) reported that their general practitioner (GP) could not test them for COVID‐19 and 293 (15.9%) patients who stated they did not have a GP (Table 2). A minority of patients did not use their GP for screening because of the cost (n = 22; 1.2%) or because they thought that the illness was too specialised for care by a GP (n = 47; 2.6%).

For these patients presenting to ED for COVID‐19 screening, the survey explored the catalyst for them choosing to attend (Table 2). Most commonly, either a telephone health service referred them (n = 578; 31.3%) or patients presented after making an independent decision to do so (n = 570; 30.9%). Other reasons for attending included being referred by a GP (n = 344; 18.6%) or an employer required the patient to be tested (n = 220; 11.9%).

Patients had accessed a variety of sources for information about COVID‐19, primarily accessing information from government websites (n = 1262; 68.4%), the internet (n = 946; 51.3%) and social media (n = 564; 30.6%).

Discussion

These data provide the first contemporary review of the patients presenting to a tertiary ED for COVID‐19 screening during a period before widespread community transmission. Of note, most patients had either mild or no symptoms and would not have presented to the ED had they known they did not have COVID‐19. Of those who did present, a significant proportion (55.3%) did not meet testing criteria. Further, few patients presenting to the screening clinic thought that their illness was either too severe or too specialised, for their GP to manage. Patients had sought information from a variety of sources about COVID‐19.

We had a good (78%) response rate and included non‐English speaking patients. However, our study has some limitations. Some patients did not answer all questions. The survey was conducted in a single ED with only those who had presented to the ED (and not other healthcare providers such as GPs) so our results may not generalise to patient groups beyond our setting. Further, we excluded patients who were assessed at triage to require active medical treatment or resuscitation, which may result in an under‐representation of the true number of severe cases presenting to the ED for COVID‐19 screening. The survey was based on self‐report and we were unable to verify patient responses (e.g. if they had tried to but been unable to get an appointment with a GP).

Our data have several clinical and policy implications. Ideally, only patients who require COVID‐19 testing based on current epidemiological or clinical history should present for screening, with perhaps only those who are unwell presenting to EDs. Given that most patients who presented to our ED had mild symptoms or did not meet testing criteria, serious consideration must be given to re‐directing such patients to an alternate service. Failing to do so before patients present to an ED will almost certainly result in EDs becoming overwhelmed if there is a surge of unwell patients presenting with COVID‐19 related respiratory failure.

Re‐directing well patients or those with only mild illness will require accurate triaging as well as alternative services. Possibilities for alternate services to conduct triaging incorporating epidemiological and clinical histories include a hotline, community‐based screening service, GP practices or self‐screening via an app/online service. Those patients who do warrant testing for SARS‐CoV‐2 could then be directed to an appropriate service, with well patients being directed to a community clinic or general practice and unwell patients being referred to ED with their specialised services in critical care. Our data suggest patients are willing to be screened in the community, as demonstrated by the small proportion of patients who reported that they thought the illness was too specialised for GPs to manage. Future research may wish to undertake more comprehensive assessment of patients' willingness to seek alternative models of testing (such as shopping centre‐based or home screening) – these were not yet widely available during the survey period.

Although we collected data over a brief period, we saw no decline in the proportion of patients presenting who did not meet criteria for testing, despite widespread public messaging about screening criteria at the time. Given that patients in the present study had accessed a variety of sources for COVID‐19 information, consistent triaging and messaging across these services about who should and should not be tested will be vital to minimise unnecessary screening.

Conclusions

Under the scenario of increasing cases, the COVID‐19 pandemic may cause a sustained surge of patients to EDs around Australia. In order to avoid additional unnecessary burden on the public health system, it is imperative the right patient is treated at the right facility. During this pandemic phase, there will be an urgent need to explore alternative avenues for testing and assessment of patients with milder illness away from hospitals. This will ensure the right patient is treated at the right facility.

Acknowledgements

RMH ED COVID‐19 Working Group: Nicola Walsham, Ben Smith, David Camilleri, Susan Harding, Steve Pincus, Emma Gardiner, Emma Smith, Naomi Watson, Bruce Garbutt, Cherylnn McGurgan, Elizabeth Bradbury. The Murdoch Children's Research Institute is funded through Victorian Operating Fund. HH holds a NHMRC Practitioner fellowship grant GN1136222. AR is funded by Open Philanthropies.

Author contributions

AR, MD, JK, MP: Research design. AR, MD, JK, MP: Data collection. AR, MD, DP, RP, MP, HH, JK: Results analysis and interpretation. AR, MD, DP, RP, MP, HH, JK: Drafting and critical revision of the article. All authors: final approval of the version to be published.

Competing interests

None declared.

Amanda Rojek, MBBS, DPhil, Fellow in Emerging Infectious Diseases; Martin Dutch, FACEM, MPH&TM, Emergency Physician; Daniel Peyton, FRACP, MPH, Paediatrician; Rachel Pelly, BPsySci (Hons), Research Assistant; Mark Putland, FACEM, Director of Emergency Department; Harriet Hiscock, FRACP, MD, Professor of Paediatrics; Jonathan Knott, FACEM, PhD, Emergency Physician.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- 1. Guan W‐J, Ni Z‐Y, Hu Y et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020; 382: 1708–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA 2020; 323: 1239–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wuhan Municipal Health Commission . Report of Clustering Pneumonia of Unknown Etiology in Wuhan City. 2019. [Cited Mar 2020.] Available from URL: http://wjw.wuhan.gov.cn/front/web/showDetail/2019123108989

- 4. Murphy B. Chief Medical Officer update on coronavirus testing. News GP. 2020. [Cited Mar 2020.] Available from URL: https://www1.racgp.org.au/newsgp/professional/chief‐medical‐officer‐update‐on‐coronavirus‐testin

- 5. Department of Health . Australian Health Sector Emergency Response Plan for Novel Coronavirus 2019. 2020. [Cited 4 Mar 2020.] Available from URL: https://www.health.gov.au/resources/publications/australian‐health‐sector‐emergency‐response‐plan‐for‐novel‐coronavirus‐covid‐19

- 6. Rojek AM, Dutch M, Camilleri D et al. Early clinical response to a high consequence infectious disease outbreak: insights from COVID‐19. Med. J. Aust. 2020; 212: 447–50.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Department of Health and Human Services . Health Services and General Practice – Coronavirus Disease (COVID‐19). 2020. [Cited 30 Mar 2020.] Available from URL: https://www.dhhs.vic.gov.au/health‐services‐and‐general‐practitioners‐coronavirus‐disease‐covid‐19

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.