Abstract

The fibrinogen-to-albumin ratio (FAR), reflecting the systemic coagulation, nutritional and inflammation status of patients, has matured into a prognostic marker for several tumor types. However, only a few studies have assessed the utility of the FAR as a prognostic indicator in patients with advanced gastric cancer (GC) receiving first-line chemotherapy. In the present study, 273 patients with advanced GC who received first-line chemotherapy between January 2014 and January 2019 at the Cancer Hospital of China Medical University (Shenyang, China) were retrospectively analyzed. Using the cut-off values determined by receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis, the patients were divided into low-FAR (≤10.03) and high-FAR (>10.03), low-fibrinogen (<3.8 g/l) and high-fibrinogen (≥3.8 g/l), and low-albumin (<40.55 g/l) and high-albumin (≥40.55 g/l) groups. The associations of the pretreatment FAR and clinicopathological characteristics with progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) were evaluated. In order to estimate the prognostic value of the FAR for patients with poor prognosis or normal fibrinogen and albumin levels, subgroup analyses were performed. The FAR had a higher area under the ROC curve (0.690; 95% CI: 0.628–0.752; P<0.001) compared with either fibrinogen or albumin alone, which are common indicators of coagulation, nutritional and inflammatory indices. A high FAR was significantly associated with a more advanced stage, peritoneal metastasis, increased CA72-4 levels and anemia (all P<0.05). On survival analysis, a low FAR was associated with a longer PFS and OS compared with a high FAR (202 vs. 130 days and 376 vs. 270 days, respectively; both P<0.001), while the hazard ratio (HR) and P-values of the FAR were lower compared with those of fibrinogen and albumin alone on multivariate analysis (PFS: HR=0.638, 95% CI: 0.436–0.932, P=0.020; OS: HR=0.568, 95% CI: 0.394–0.819, P=0.002). Subgroup analysis indicated that among patients with poor prognosis, including multiple metastases, TNM stage IV and abnormal CA72-4 levels, the FAR may be used as an accurate prognostic marker (all P<0.05), and may also reliably identify patients with poor prognosis among those with normal fibrinogen and albumin levels (all P<0.001). The FAR was indicated to be a valuable marker for predicting PFS and OS in patients with advanced GC receiving first-line chemotherapy and is superior to either fibrinogen or albumin alone.

Keywords: fibrinogen-to-albumin ratio, gastric cancer, first-line chemotherapy, prognosis, progression-free survival, overall survival

Introduction

Gastric cancer (GC) is the third leading cause of cancer-associated mortality worldwide and the high incidence of GC poses a major threat to public health globally (1). At present, GC may be cured by radical resection; however, for patients with advanced-stage disease that can no longer receive radical surgical treatment, the median survival time after treatment with trastuzumab plus chemotherapy is only 13.8 months, the improvement of which poses a challenge to scientists and oncologists (2). Therefore, it is necessary to identify patients with poor prognosis as soon as possible, which will help doctors optimize treatment programs and improve the prognosis and quality of life of patients with advanced GC. The Union for International Cancer Control TNM classification system is one of the most common methods used by clinicians to evaluate the prognosis of patients with GC (3). However, this system has certain limitations, such as the fact that patients with the same tumor stage may have different clinical outcomes (4,5). Therefore, it is imperative to identify other independent prognostic markers for GC to further classify patients who have been staged according to the TNM system into subgroups with good and poor prognosis. The addition of other well-proven markers should enable doctors to treat patients with poor prognosis in a more timely and effective manner.

Tumorigenesis is a multifactorial process. Hypercoagulability, inflammation and malnutrition promote the occurrence, development, recurrence and metastasis of tumors and are associated with poor treatment outcomes (6–11). Analysis of existing data has demonstrated that conditions of hypercoagulability, inflammation and poor nutritional status are independent prognostic factors for poor prognosis of patients with GC. As a marker reflecting coagulation function nutritional and the inflammatory status of patients, several studies have used the fibrinogen-to-albumin ratio (FAR) or albumin-to-fibrinogen ratio (AFR) to evaluate the prognosis of various cancer patients, including those with GC, and have found that increased FAR or decreased AFR levels were associated with poor prognosis in cancer patients (12–17). Another critical role of FAR or AFR is to assess the effect of the chemotherapy regimen in a particular population to guide the selection of an optimal therapy (18–20). However, there are currently few reports on the pretreatment FAR being used as a marker to predict progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) in patients with GC undergoing first-line chemotherapy.

The aim of the present study was to investigate whether the pretreatment FAR may serve as a multifunctional marker for predicting PFS and OS in patients with advanced GC receiving first-line chemotherapy.

Materials and methods

Patient characteristics

The data of patients with non-resectable GC from the Cancer Hospital of China Medical University (Shenyang, China) between January 2014 and January 2019 were retrospectively evaluated. All patients included were required to fulfill the following criteria: i) The diagnosis was pathologically confirmed; ii) the TNM stage for patients with GC unable to undergo radical resection was considered only as stage III–IV; iii) the patients included in the data collection received no adjuvant chemoradiotherapy; iv) no severe coagulation disorders, nutritional therapy, acute infections or other inflammatory conditions prior to specimen collection; and v) blood sample collection performed within 1 week prior to the initial first-line chemotherapy. A total of 273 patients with advanced GC meeting the inclusion criteria were included in the present retrospective study, 183 of whom were male and 90 were female. The study protocol was approved by the Cancer Hospital of China Medical University Ethics Committee (Shenyang, China).

Clinical data collection and follow-up

In all patients included in the study, computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging or other accepted imaging examinations were used to determine the presence of metastatic lymph nodes and organs. The reference range for plasma fibrinogen, albumin and hemoglobin was 2–4, 35–55 and 115–155 g/l, respectively. The accepted normal range for carcinoembryonic antigen, CA19-9 and CA72-4 was 0–5 ng/ml, 0–37 U/ml and 0–6 U/ml, respectively. The FAR was calculated as follows: FAR=fibrinogen (g/l)/albumin (g/l) ×100%.

The primary chemotherapeutic regimens for patients receiving first-line chemotherapy are as follows: SOX (oxaliplatin + S1)/CapeOX (oxaliplatin + capecitabine), FOLFOX (oxaliplatin + leucovorin + 5-fluorouracil) and DCF (docetaxel + cisplatin + 5-fluorouracil)/DOF (docetaxel + oxaliplatin + 5-fluorouracil). A total of 137 patients received SOX/CapeOX regimen, 49 patients received FOLFOX regimen, 36 patients received DCF/DOF regimen and 51 patients received S1 or capecitabine monotherapy. The efficacy of treatment was evaluated every 2–3 cycles. The Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors version 1.1 were employed to estimate the response to chemotherapy (21). Patients with first-line chemotherapy failure were followed up every 2–3 months. The latest follow-up date was December 2019. PFS and OS were considered as the primary endpoints. PFS was defined as the time from start of first-line chemotherapy until the first observed progression or the last follow-up visit without progression, while OS was defined as the time from the beginning of first-line chemotherapy to death from any cause or the end of follow-up.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was performed using SPSS v21 (IBM, Corp.). Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was applied to calculate the cut-off values of the FAR, fibrinogen and albumin. Fisher's exact test and the χ2 test were employed to evaluate the association between the FAR and the clinicopathological characteristics. Univariate and multivariate data analyses were conducted to identify potential predictors of PFS and OS. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to construct survival curves. The survival of patients was compared with the log-rank test. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistical significant difference.

Results

Optimal cut-off value of the FAR

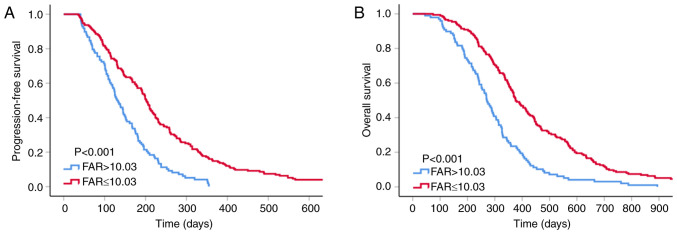

In addition to the FAR, the present study also assessed fibrinogen and albumin to determine whether the FAR is superior to either fibrinogen or albumin alone in predicting the prognosis of patients with GC. The area under the ROC curve (AUC) is considered to indicate the overall diagnostic power of a model, with a larger AUC indicating better diagnostic power of the prognostic predictor. In order to assess the ability of the FAR to discriminate between patients with advanced GC with different prognosis, ROC curve analysis was performed to determine the optimal cut-off values of the FAR, fibrinogen and albumin, and the AUC values of these three indicators were further compared. The median overall survival of 339 days was used as the fixed variable and the levels of FAR, fibrinogen and albumin as the test variables to determine the cut-off values. The optimal cut-off values of the FAR, fibrinogen and albumin were 10.033, 3.795 and 40.550, respectively. The FAR had a higher AUC value (0.690; 95% CI: 0.628–0.752; P<0.001) compared with fibrinogen (0.657; 95% CI: 0.593–0.721; P<0.001) and albumin (0.660; 95% CI: 0.596–0.724; P<0.001; Fig. 1), which indicated that the FAR is likely superior to fibrinogen and albumin alone in predicting the prognosis of patients with GC. The cut-off values of the FAR, fibrinogen and albumin were set as 10.03, 3.80 and 40.55, respectively, in the further analyses and patients with FAR >10.03, fibrinogen ≥3.80 and albumin ≥40.55 comprised the high-FAR group, whereas the remaining patients comprised the low-FAR group.

Figure 1.

ROC curve analyses for prognostic indicators in patients with advanced gastric cancer. ROC, receiver operating characteristic; FAR, fibrinogen-to-albumin ratio.

Association of clinicopathological characteristics with the FAR

Of the 273 patients included in the present study, 183 (67.03%) were male and 90 (32.97%) were female. The median age was 60 years (range, 52–65 years) and the median body mass index was 21.6 kg/m2 (range, 19.6–23.6 kg/m2). There were 80 (29.30%) patients with peritoneal metastasis and 220 (80.59%) patients with stage IV disease. Patients with a CA72-4 level >6 U/ml and hemoglobin <115 g/l accounted for 57.51 and 38.46% of the total, respectively (Table I).

Table I.

Association between pretreatment FAR and clinicopathological characteristics.

| Variable | All | Low FAR | High FAR | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 273 (100.0) | 175 (64.10) | 98 (35.90) | |

| Age (years) | 0.057 | |||

| <60 | 135 (49.45) | 79 (45.14) | 56 (57.14) | |

| ≥60 | 138 (50.55) | 96 (54.86) | 42 (42.86) | |

| Sex | 0.726 | |||

| Male | 183 (67.03) | 116 (66.29) | 67 (68.37) | |

| Female | 90 (32.97) | 59 (33.71) | 31 (31.63) | |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 0.965 | |||

| <18.5 or >25 | 72 (26.37) | 46 (26.29) | 26 (26.53) | |

| 18.5–25 | 201 (73.63) | 129 (73.71) | 72 (73.47) | |

| ECOG PS score | 0.695 | |||

| 0-1 | 228 (83.52) | 145 (82.86) | 83 (84.69) | |

| >1 | 45 (16.48) | 30 (17.14) | 15 (15.31) | |

| Histological differentiation | 0.050 | |||

| High/moderate | 72 (26.37) | 53 (30.29) | 19 (19.39) | |

| Poor/mucinous | 201 (73.63) | 122 (69.71) | 79 (80.61) | |

| Number of organs with metastasis | 0.486 | |||

| 0-1 | 180 (65.93) | 118 (67.43) | 62 (63.27) | |

| >1 | 93 (34.07) | 57 (32.57) | 36 (36.73) | |

| Peritoneal metastasis | 0.010 | |||

| Yes | 80 (29.30) | 42 (24.00) | 38 (38.78) | |

| No | 193 (70.70) | 133 (76.00) | 60 (61.22) | |

| TNM stage | 0.025 | |||

| III | 53 (19.41) | 41 (23.43) | 12 (12.24) | |

| IV | 220 (80.59) | 134 (76.57) | 86 (87.76) | |

| CEA (ng/ml) | 0.691 | |||

| ≤5 | 152 (55.68) | 99 (56.57) | 53 (54.08) | |

| >5 | 121 (44.32) | 76 (43.43) | 45 (45.92) | |

| CA19-9 (U/ml) | 0.264 | |||

| ≤37 | 168 (61.54) | 112 (64.00) | 56 (57.14) | |

| >37 | 105 (38.46) | 63 (36.00) | 42 (42.86) | |

| CA72-4 (U/ml) | 0.027 | |||

| ≤6 | 116 (42.49) | 83 (47.43) | 33 (33.67) | |

| >6 | 157 (57.51) | 92 (52.57) | 65 (66.33) | |

| Hemoglobin (g/l) | 0.031 | |||

| <115 | 105 (38.46) | 59 (33.71) | 46 (46.94) | |

| ≥115 | 168 (61.54) | 116 (66.29) | 52 (53.06) |

Values are expressed as n (%). FAR, fibrinogen-to-albumin ratio; ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status.

There were certain differences in the clinicopathological characteristics between the low-FAR and the high-FAR groups. An elevated FAR was significantly associated with peritoneal carcinomatosis (P=0.010), stage IV cancer (P=0.025), increased CA72-4 levels (P=0.027) and anemia (P=0.031). The clinicopathological characteristics of the patients are further described in detail in Table I.

Prognostic factors indicating patient survival

As presented in Table II, univariate analyses revealed that metastasis in >1 organ (P=0.003), peritoneal metastasis (P<0.001), TNM stage IV (P=0.026) and increased CA72-4 levels (P=0.001) were significantly associated with shorter PFS, while increased albumin (P=0.003) and reduced fibrinogen (P<0.001) and FAR (P<0.001) levels were significantly associated with longer PFS. On multivariate analysis, only peritoneal metastasis (P=0.042), CA72-4 levels (P=0.013), albumin (P=0.048) and FAR (P=0.020) were indicated to be independently associated with PFS. As the P-value of FAR (P=0.020) was lower compared with that of fibrinogen (P=0.231) and albumin (P=0.048) alone, the FAR was considered as significantly more effective than either fibrinogen or albumin alone in predicting PFS in patients with GC.

Table II.

Associations of PFS with FAR and other clinicopathological factors.

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor | HR | 95% CI | P-value | HR | 95% CI | P-value |

| Age >60 years | 0.988 | 0.778–1.255 | 0.921 | |||

| Male sex | 1.140 | 0.884–1.471 | 0.313 | |||

| Body mass index | ||||||

| <18.5 or >25 kg/m2 | 0.940 | 0.717–1.231 | 0.651 | |||

| ECOG PS score >1 | 1.295 | 0.940–1.784 | 0.114 | 1.164 | 0.832–1.629 | 0.376 |

| Histological differentiation, poor/mucinous | 1.144 | 0.873–1.500 | 0.329 | |||

| Metastasis in >1 organ | 1.464 | 1.138–1.883 | 0.003 | 1.232 | 0.920–1.651 | 0.162 |

| Peritoneal metastasis | 1.813 | 1.388–2.367 | <0.001 | 1.370 | 1.011–1.857 | 0.042 |

| TNM stage IV | 1.412 | 1.042–1.913 | 0.026 | 1.060 | 0.759–1.481 | 0.731 |

| CEA >5 ng/ml | 1.162 | 0.913–1.480 | 0.223 | |||

| CA19-9 >37 U/ml | 0.972 | 0.761–1.243 | 0.823 | |||

| CA72-4 >6 U/ml | 1.506 | 1.178–1.926 | 0.001 | 1.375 | 1.068–1.770 | 0.013 |

| Hemoglobin <115 g/l | 0.919 | 0.718–1.176 | 0.502 | |||

| Fibrinogen <3.8 g/l | 0.567 | 0.441–0.729 | <0.001 | 0.805 | 0.564–1.149 | 0.231 |

| Albumin ≥40.55 g/l | 0.697 | 0.547–0.887 | 0.003 | 0.770 | 0.595–0.998 | 0.048 |

| FAR ≤10.03 | 0.468 | 0.360–0.608 | <0.001 | 0.638 | 0.436–0.932 | 0.020 |

FAR, fibrinogen-to-albumin ratio; PFS, progression-free survival; ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; HR, hazard ratio.

As presented in Table III, metastasis to >1 organ (P=0.030), peritoneal metastasis (P<0.001) and CA72-4 levels >6 U/ml (P=0.033) were identified as risk factors adversely affecting the OS of patients with GC, while an age of >60 years (P=0.040), fibrinogen <3.8 g/l (P<0.001), albumin ≥40.55 g/l (P<0.001) and FAR ≤10.03 (P<0.001) were indicated to be protective factors favorably affecting the OS of patients with GC on univariate analysis. The results of the multivariate analysis demonstrated that the OS of patients with GG was independently associated with peritoneal metastasis (P=0.019), albumin (P=0.016) and FAR (P=0.002). FAR (P=0.002) was superior to fibrinogen (P=0.938) and albumin (P=0.016) in predicting the OS of patients with GC.

Table III.

Associations of OS with FAR and other clinicopathological factors.

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor | HR | 95% CI | P-value | HR | 95% CI | P-value |

| Age >60 years | 0.778 | 0.612–0.989 | 0.040 | 0.869 | 0.674–1.120 | 0.278 |

| Male sex | 1.136 | 0.881–1.465 | 0.324 | |||

| Body mass index | ||||||

| <18.5 or >25 kg/m2 | 1.014 | 0.774–1.329 | 0.921 | |||

| ECOG PS score >1 | 1.304 | 0.946–1.798 | 0.105 | 1.196 | 0.858–1.668 | 0.291 |

| Histological differentiation, poor/mucinous | 1.268 | 0.968–1.661 | 0.084 | 1.096 | 0.832–1.444 | 0.516 |

| Metastasis in >1 organ | 1.326 | 1.028–1.709 | 0.030 | 1.166 | 0.884–1.537 | 0.277 |

| Peritoneal metastasis | 1.932 | 1.478–2.524 | <0.001 | 1.441 | 1.063–1.955 | 0.019 |

| TNM stage IV | 1.188 | 0.879–1.605 | 0.263 | |||

| CEA >5 ng/ml | 1.123 | 0.884–1.428 | 0.342 | |||

| CA19-9 >37 U/ml | 1.072 | 0.839–1.369 | 0.578 | |||

| CA72-4 >6 U/ml | 1.301 | 1.021–1.656 | 0.033 | 1.224 | 0.951–1.574 | 0.116 |

| Hemoglobin <115 g/l | 0.932 | 0.729–1.192 | 0.575 | |||

| Fibrinogen <3.8 g/l | 0.628 | 0.490–0.804 | <0.001 | 0.986 | 0.695–1.399 | 0.938 |

| Albumin ≥40.55 g/l | 0.635 | 0.498–0.810 | <0.001 | 0.725 | 0.559–0.941 | 0.016 |

| FAR ≤10.03 | 0.463 | 0.358–0.599 | <0.001 | 0.568 | 0.394–0.819 | 0.002 |

FAR, fibrinogen-to-albumin ratio; OS, overall survival; ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; HR, hazard ratio.

Survival analysis according to pretreatment FAR

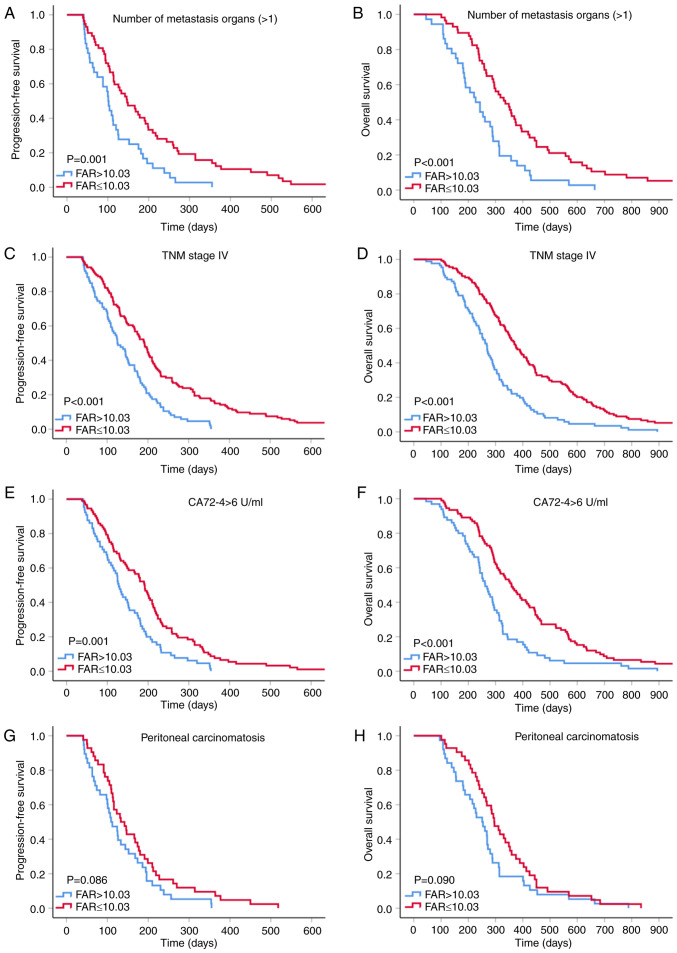

The median PFS and OS of the patients included in the present study were 174 and 339 days, respectively. The low-FAR group had longer median PFS and OS compared with the high-FAR group (202 vs. 130 days, P<0.001; and 376 vs. 270 days, P<0.001, respectively; Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier curves for (A) progression-free and (B) overall survival according to the cut-off value of FAR in patients. FAR, fibrinogen-to-albumin ratio.

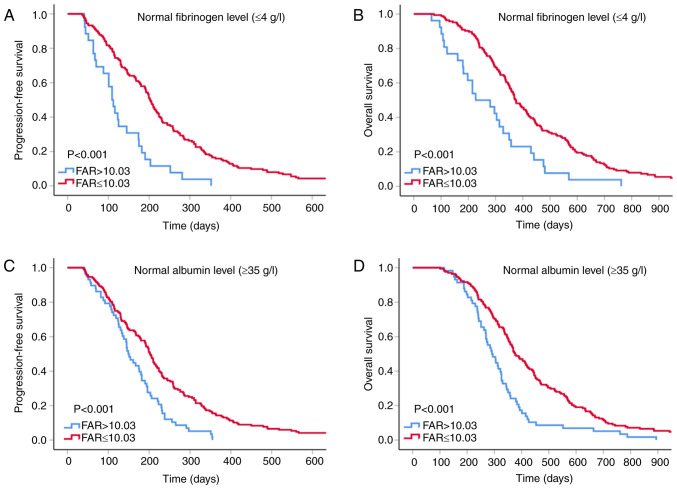

Survival analysis for the FAR according to the prognostic factor subtypes of GC

Previous studies demonstrated that distant metastasis, peritoneal infiltration, TNM stage IV disease and increased CA72-4 levels are crucial characteristics indicating unfavorable prognosis in patients with GC (22–24). Therefore, a subgroup analysis was performed to investigate whether the pretreatment FAR is able to further predict the outcomes of patients with GC with poor prognosis (Fig. 3). The results suggested improved PFS and OS in the low-FAR group within the subgroups with >1 metastatic organ (P=0.001 and P<0.001), stage IV cancer (all P<0.001) and elevated CA72-4 levels (P=0.001 and P<0.001). Although GC patients with low FAR within the peritoneal invasion subgroup tended to have longer PFS and OS, there was no statistical insignificance (all P>0.05) and this result may have been obtained due to the small sample size (n=80).

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier curves for FAR according to various risk groups. (A) PFS and (B) OS for number of metastasis organs (>1); (C) PFS and (D) OS for patients with TNM stage IV; (E) PFS and (F) OS for patients with CA72-4 >6 U/ml; (G) PFS and (H) OS for patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis. FAR, fibrinogen-to-albumin ratio; PFS, progression-free survival; OS, overall survival.

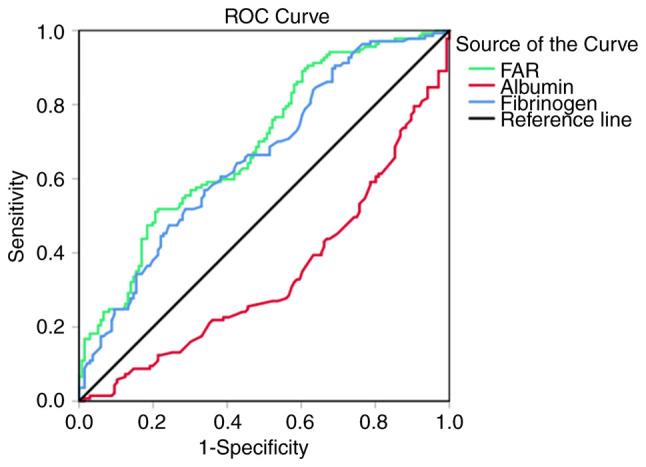

For patients with normal albumin and fibrinogen levels, clinicians may be prone to overlooking the coagulation, inflammation and nutritional status that may indicate the prognosis of such patients. Thus, a subgroup analysis was performed to investigate whether the FAR is able to provide a clue as to the prognosis of patients with normal albumin and fibrinogen indices. The results suggested that low FAR within normal plasma fibrinogen and albumin level subgroups of patients with GC was an indicator of longer PFS and OS (all P<0.001; Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Kaplan-Meier curves for FAR for patients with normal levels of fibrinogen and albumin. (A) PFS and (B) OS for patients with normal fibrinogen; (C) PFS and (D) OS for patients with normal albumin levels. FAR, fibrinogen-to-albumin ratio; PFS, progression-free survival; OS, overall survival.

Discussion

Previous studies have reported the importance of the FAR in predicting the prognosis of different types of cancer (25–29). Zhang et al (30) indicated that a reduced AFR was an independent predictor of poor OS in surgical stage II and III GC. In the present study, it was determined that patients with GC and a high FAR had shortened OS. In other words, the previous and the present study suggested that patients with elevated fibrinogen levels and decreased albumin levels had poor prognosis. Therefore, the conclusion regarding the prognostic value of AFR and FAR for predicting the OS of patients with GC in these two studies are similar. However, the patient characteristics of the present cohort are different from those in the previous study: The patients of the present study had stage III–IV unresectable GC and all patients received first-line chemotherapy. To the best of our knowledge, the present study was the first study to indicate that the FAR may be an independent predictor of first-line chemotherapy-associated PFS and long-term OS in patients with advanced GC. Furthermore, the prognostic value of the FAR was more powerful compared with that of either fibrinogen or albumin alone. The most noteworthy result of the present study was that the subgroup analysis results demonstrated that the FAR may be a cost-effective and accessible marker for patients with poor prognosis to further predict the clinical outcomes of these populations. Furthermore, the FAR may be a reliable indicator for predicting the prognosis of patients with normal albumin and fibrinogen levels that may otherwise not draw the physicians' attention. Therefore, physicians may be able to formulate personalized treatment patterns for patients with GC with different prognosis by effectively applying the FAR.

There is increasing and credible evidence that cancer-associated hypercoagulability, inflammation and malnutrition are highly prevalent among cancer patients. These abnormal conditions may weaken the response of tumor patients to treatment and promote the occurrence, development, metastasis and exacerbation of cancer (31–36). The potential mechanism may be as follows: First, patients with malignant tumors may occasionally be in a hypercoagulable state, which may manifest as venous thromboembolism and disseminated intravascular coagulation. Although thrombosis may not be common among patients with advanced cancer, systemic hypercoagulability is frequently observed. The coagulation cascade has a crucial role in tumor growth. Components involved in the hypercoagulable state provide a stable framework for the tumor extracellular matrix, which sets the conditions for angiogenesis, adhesion, migration and invasion of tumor cells. The interaction of coagulation cytokines may also impede the cytotoxicity of immune cells against tumor cells (37). Furthermore, cytokines may also induce tumor cell proliferation and invasion by mediating the adhesion between leukocytes and endothelial cells, which promotes inflammation (38).

Second, inflammation is a hallmark of cancer (39). Inflammation may lead to mutagenesis, predisposing to the accumulation of mutations in tumor protein 53 and other cancer-associated genes and chronic inflammation that induces tissue damage may disrupt the barrier function, expose the stem cell region to environmental carcinogens or facilitate stem cells to be eroded by genotoxic compounds, which may trigger tumor formation (40). Kim et al (41) reported that tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α and Toll-like receptor family member-2 (TLR2) may be essential for cancer metastasis. Cancer cells may trigger macrophage activity, which promotes the production of TNF-α by activating TLR2. The extracellular matrix proteoglycan versican, which is elevated in tumors, augments metastatic cancer growth by triggering TLR2 complexes and causing TNF-α release. These factors create an inflammatory microenvironment, which promotes metastatic growth (41).

Finally, malnutrition is universal among cancer patients receiving oncological treatment. Patients suffering from malnutrition have lower tumor treatment completion rates, poorer quality of life and more complications, which ultimately leads to lower survival rates (42). Malnutrition may cause fluctuation in the bone marrow stromal microenvironment, debilitate hematopoiesis and trigger thymic atrophy through apoptosis of immature CD4/CD8 double-positive thymocytes, thereby promoting a decline in immunity, which facilitates the proliferation of tumor cells (43).

Previous studies have demonstrated that anti-coagulant therapy, anti-inflammatory treatment and nutritional support may reduce susceptibility to cancer, prevent disease exacerbation and improve the clinical outcome (44–46). As a reliable prognostic indicator, the FAR relies on fibrinogen and albumin. Fibrinogen is an acute-phase protein produced by the liver and its plasma levels increase under hypercoagulable and inflammatory conditions (47–49). A large body of evidence indicated that fibrinogen-related coagulation dysfunction is tightly linked to cancer angiogenesis, invasion, progression and metastasis (50,51). Reliable data have demonstrated that elevated fibrinogen levels are associated with poor prognosis of patients with cancer, including GC (52,53). Albumin is also produced by liver cells. The tumor-associated proinflammatory cytokines TNF-α and interleukin-6 are able to inhibit albumin production by hepatocytes (54). The decrease in plasma albumin levels indicates a high degree of inflammation, poor nutritional status and poor treatment efficacy (55,56). Albumin has also been investigated for its potential value in predicting shorter survival in a number of cancer types, including GC (57,58).

As mentioned above, albumin and fibrinogen are important prognostic indicators for patients with GC, but their accuracy may be compromised by certain factors, such as dehydration or fluid retention. The results of the present ROC curve analysis demonstrated that the AUC of the FAR (0.690) was higher compared with that of fibrinogen (0.657) and albumin (0.660), and the P-value of FAR (PFS: P=0.020; OS: P=0.002) was lower compared with that of fibrinogen (PFS: P=0.231; OS: P=0.938) and albumin (PFS: P=0.048; OS: P=0.016) on multivariate analyses, which indicated that the prognostic value of the FAR was superior to that of either fibrinogen or albumin alone.

Based on the results of the present study, clinicians may use the FAR to distinguish patients with poor prognosis and personalize treatment to improve their quality of life and prolong survival. There were certain limitations to the present study. First, as this was a single-center retrospective study, the usefulness of the FAR requires verification by multicenter large-scale studies. Furthermore, a total of 273 patients included in the present study, which is a small sample size and may be insufficient to draw definitive conclusions.

In conclusion, the FAR prior to first-line chemotherapy may help identify specific patient populations that are likely to benefit from chemotherapy and is an independent predictor of PFS and OS; therefore, it may be used as an innovative, dependable prognostic index for patients with advanced-stage GC.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (grant no. 2018YFC1311600), the Scientific Research Foundation for the Introduction of Talents, Liaoning Cancer Hospital & Institute (grant no. Z1702), the Science and Technology Planning Project of Liaoning Province of China (grant no. 201800449) and the Science and Technology Planning Project of Shenyang (grant no. 191124088).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors' contributions

LZ analyzed the patient data and was a major contributor in writing the manuscript. LZ, ZW, JX, ZZ, HL, YW, QD, HP, QW, FB, FL and JZ performed the retrospective analysis of patients. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This project was approved by the Ethical Committee of the Cancer Hospital of China Medical University (Shenyang, China). Due to the retrospective nature of this study the Ethics Committee waived written informed consent of the included patients.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

All the authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:394–424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bang YJ, Van Cutsem E, Feyereislova A, Chung HC, Shen L, Sawaki A, Lordick F, Ohtsu A, Omuro Y, Satoh T, et al. Trastuzumab in combination with chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone for treatment of HER2-positive advanced gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction cancer (ToGA): A phase 3, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2010;376:687–697. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61121-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fang C, Wang W, Deng JY, Sun Z, Seeruttun SR, Wang ZN, Xu HM, Liang H, Zhou ZW. Proposal and validation of a modified staging system to improve the prognosis predictive performance of the 8th AJCC/UICC pTNM staging system for gastric adenocarcinoma: A multicenter study with external validation. Cancer Commun (Lond) 2018;38:67. doi: 10.1186/s40880-018-0337-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yoon JY, Sigel K, Martin J, Jordan R, Beasley MB, Smith C, Kaufman A, Wisnivesky J, Kim MK. Evaluation of the prognostic significance of TNM staging guidelines in lung carcinoid tumors. J Thorac Oncol. 2019;14:184–192. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2018.10.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shao Y, Geng Y, Gu W, Ning Z, Huang J, Pei H, Jiang J. Assessment of lymph node ratio to replace the pn categories system of classification of the tnm system in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. J Thorac Oncol. 2016;11:1774–1784. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2016.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khorana AA, Fine RL. Pancreatic cancer and thromboembolic disease. Lancet Oncol. 2004;5:655–663. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(04)01606-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miller GJ, Bauer KA, Howarth DJ, Cooper JA, Humphries SE, Rosenberg RD. Increased incidence of neoplasia of the digestive tract in men with persistent activation of the coagulant pathway. J Thromb Haemost. 2004;2:2107–2114. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2004.01011.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Balkwill F, Mantovani A. Inflammation and cancer: Back to Virchow? Lancet. 2001;357:539–545. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04046-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mantovani A, Allavena P, Sica A, Balkwill F. Cancer-related inflammation. Nature. 2008;454:436–444. doi: 10.1038/nature07205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arends J, Bodoky G, Bozzetti F, Fearon K, Muscaritoli M, Selga G, van Bokhorst-de van der Schueren MA, von Meyenfeldt M, DGEM (German Society for Nutritional Medicine) Zürcher G, et al. ESPEN guidelines on enteral nutrition: Non-surgical oncology. Clin Nutr. 2006;25:245–259. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2006.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bozzetti F, Arends J, Lundholm K, Micklewright A, Zurcher G, Muscaritoli M; ESPEN. ESPEN Guidelines on parenteral nutrition: Non-surgical oncology. Clin Nutr. 2009;28:445–454. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2009.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xu Q, Yan Y, Gu S, Mao K, Zhang J, Huang P, Zhou Z, Chen Z, Zheng S, Liang J, et al. A novel inflammation-based prognostic score: The fibrinogen/albumin ratio predicts prognoses of patients after curative resection for hepatocellular carcinoma. J Immunol Res. 2018;2018:4925498. doi: 10.1155/2018/4925498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang YY, Liu ZZ, Xu D, Liu M, Wang K, Xing BC. Fibrinogen-albumin ratio index (fari): A more promising inflammation-based prognostic marker for patients undergoing hepatectomy for colorectal liver metastases. Ann Surg Oncol. 2019;26:3682–3692. doi: 10.1245/s10434-019-07586-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xu WY, Zhang HH, Xiong JP, Yan XB, Bai Y, Lin JZ, Long JY, Zheng YC, Zhao HT, Sang XT. Prognostic significance of the fibrinogen-to-albumin ratio in gallbladder cancer patients. World J Gastroenterol. 2018;24:3281–3292. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v24.i29.3281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li SQ, Jiang YH, Lin J, Zhang J, Sun F, Gao QF, Zhang L, Chen QG, Wang XZ, Ying HQ. Albumin-to-fibrinogen ratio as a promising biomarker to predict clinical outcome of non-small cell lung cancer individuals. Cancer Med. 2018;7:1221–1231. doi: 10.1002/cam4.1428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zou YX, Qiao J, Zhu HY, Lu RN, Xia Y, Cao L, Wu W, Jin H, Liu WJ, Liang JH, et al. Albumin-to-fibrinogen ratio as an independent prognostic parameter in untreated chronic lymphocytic leukemia: A retrospective study of 191 cases. Cancer Res Treat. 2019;51:664–671. doi: 10.4143/crt.2018.358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.You X, Zhou Q, Song J, Gan L, Chen J, Shen H. Preoperative albumin-to-fibrinogen ratio predicts severe postoperative complications in elderly gastric cancer subjects after radical laparoscopic gastrectomy. BMC Cancer. 2019;19:931. doi: 10.1186/s12885-019-6143-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yu W, Ye Z, Fang X, Jiang X, Jiang Y. Preoperative albumin-to-fibrinogen ratio predicts chemotherapy resistance and prognosis in patients with advanced epithelial ovarian cancer. J Ovarian Res. 2019;12:88. doi: 10.1186/s13048-019-0563-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ying J, Zhou D, Gu T, Huang J, Liu H. Pretreatment albumin/fibrinogen ratio as a promising predictor for the survival of advanced non small-cell lung cancer patients undergoing first-line platinum-based chemotherapy. BMC Cancer. 2019;19:288. doi: 10.1186/s12885-019-5490-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang L, Zhang J, Wang Y, Dong Q, Piao H, Wang Q, Zhou Y, Ding Y. Potential prognostic factors for predicting the chemotherapeutic outcomes and prognosis of patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Lab Anal. 2019;33:e22958. doi: 10.1002/jcla.22958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, Schwartz LH, Sargent D, Ford R, Dancey J, Arbuck S, Gwyther S, Mooney M, et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: Revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1) Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:228–247. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Singh P, Toom S, Huang Y. Anti-claudin 18.2 antibody as new targeted therapy for advanced gastric cancer. J Hematol Onco. 2017;10:105. doi: 10.1186/s13045-017-0473-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thomassen I, van Gestel YR, van Ramshorst B, Luyer MD, Bosscha K, Nienhuijs SW, Lemmens VE, de Hingh IH. Peritoneal carcinomatosis of gastric origin: A population-based study on incidence, survival and risk factors. Int J Cancer. 2014;134:622–628. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shimada H, Noie T, Ohashi M, Oba K, Takahashi Y. Clinical significance of serum tumor markers for gastric cancer: A systematic review of literature by the task force of the japanese gastric cancer association. Gastric Cancer. 2014;17:26–33. doi: 10.1007/s10120-013-0259-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sun DW, An L, Lv GY. Albumin-fibrinogen ratio and fibrinogen-prealbumin ratio as promising prognostic markers for cancers: An updated meta-analysis. World J Surg Oncol. 2020;18:9. doi: 10.1186/s12957-020-1786-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wu M, Pan Y, Jia Z, Wang Y, Yang N, Mu J, Zhou T, Guo Y, Jiang J, Cao X. Preoperative plasma fibrinogen and serum albumin score is an independent prognostic factor for resectable stage II–III Gastric Cancer. Dis Markers. 2019;2019:9060845. doi: 10.1155/2019/9060845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li Y, Yang JN, Cheng SS, Wang Y. Prognostic significance of FA score based on plasma fibrinogen and serum albumin in patients with epithelial ovarian cancer. Cancer Manag Res. 2019;11:7697–7705. doi: 10.2147/CMAR.S211524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang Y, Xiao G. Prognostic significance of the ratio of fibrinogen and albumin in human malignancies: A meta-analysis. Cancer Manag Res. 2019;11:3381–3393. doi: 10.2147/CMAR.S198419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sun SY, Chen PP, Meng LX, Li L, Mo ZX, Sun CH, Wang Y, Liang FH. High preoperative plasma fibrinogen and serum albumin score is associated with poor survival in operable esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Dis Esophagus. 2019:32. doi: 10.1093/dote/doy057. doi: 10.1093/dote/doy057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang J, Li SQ, Liao ZH, Jiang YH, Chen QG, Huang B, Liu J, Xu YM, Lin J, Ying HQ, Wang XZ. Prognostic value of a novel FPR biomarker in patients with surgical stage II and III gastric cancer. Oncotarget. 2017;8:75195–75205. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.20661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Batschauer AP, Figueiredo CP, Bueno EC, Ribeiro MA, Dusse LM, Fernandes AP, Gomes KB, Carvalho MG. D-dimer as a possible prognostic marker of operable hormone receptor-negative breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 2010;21:1267–1272. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdp474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tsimafeyeu IV, Demidov LV, Madzhuga AV, Somonova OV, Yelizarova AL. Hypercoagulability as a prognostic factor for survival in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2009;28:30. doi: 10.1186/1756-9966-28-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dolan RD, Laird BJA, Horgan PG, McMillan DC. The prognostic value of the systemic inflammatory response in randomised clinical trials in cancer: A systematic review. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2018;132:130–137. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2018.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bilen MA, Martini DJ, Liu Y, Lewis C, Collins HH, Shabto JM, Akce M, Kissick HT, Carthon BC, Shaib WL, et al. The prognostic and predictive impact of inflammatory biomarkers in patients who have advanced-stage cancer treated with immunotherapy. Cancer. 2019;125:127–134. doi: 10.1002/cncr.31778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schütte K, Tippelt B, Schulz C, Röhl FW, Feneberg A, Seidensticker R, Arend J, Malfertheiner P. Malnutrition is a prognostic factor in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) Clin Nutr. 2015;34:1122–1127. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2014.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maasberg S, Knappe-Drzikova B, Vonderbeck D, Jann H, Weylandt KH, Grieser C, Pascher A, Schefold JC, Pavel M, Wiedenmann B, et al. Malnutrition predicts clinical outcome in patients with neuroendocrine neoplasia. Neuroendocrinology. 2017;104:11–25. doi: 10.1159/000442983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Palumbo JS, Talmage KE, Massari JV, La Jeunesse CM, Flick MJ, Kombrinck KW, Jirousková M, Degen JL. Platelets and fibrin(ogen) increase metastatic potential by impeding natural killer cell-mediated elimination of tumor cells. Blood. 2005;105:178–185. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-06-2272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ridker PM, MacFadyen JG, Thuren T, Everett BM, Libby P, Glynn RJ. Effect of interleukin-1β inhibition with canakinumab on incident lung cancer in patients with atherosclerosis: Exploratory results from a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2017;390:1833–1842. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32247-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mantovani A. Cancer: Inflaming metastasis. Nature. 2009;457:36–37. doi: 10.1038/457036b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Greten FR, Grivennikov SI. Inflammation and cancer: Triggers, mechanisms, and consequences. Immunity. 2019;51:27–41. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2019.06.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kim S, Takahashi H, Lin WW, Descargues P, Grivennikov S, Kim Y, Luo JL, Karin M. Carcinoma-produced factors activate myeloid cells through TLR2 to stimulate metastasis. Nature. 2009;457:102–106. doi: 10.1038/nature07623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Marin Caro MM, Laviano A, Pichard C. Nutritional intervention and quality of life in adult oncology patients. Clin Nutr. 2007;26:289–301. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2007.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Savino W, Dardenne M. Nutritional imbalances and infections affect the thymus: Consequences on T-cell-mediated immune responses. Proc Nutr Soc. 2010;69:636–643. doi: 10.1017/S0029665110002545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Spek CA, Versteeg HH, Borensztajn KS. Anticoagulant therapy of cancer patients: Will patient selection increase overall survival? Thromb Haemost. 2015;114:530–536. doi: 10.1160/TH15-02-0124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wu CY, Wu MS, Kuo KN, Wang CB, Chen YJ, Lin JT. Effective reduction of gastric cancer risk with regular use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in Helicobacter pylori-infected patients. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:2952–2957. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.0695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Klek S, Scislo L, Walewska E, Choruz R, Galas A. Enriched enteral nutrition may improve short-term survival in stage IV gastric cancer patients: A randomized, controlled trial. Nutrition. 2017;36:46–53. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2016.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lin Y, Liu Z, Qiu Y, Zhang J, Wu H, Liang R, Chen G, Qin G, Li Y, Zou D. Clinical significance of plasma D-dimer and fibrinogen in digestive cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2018;44:1494–1503. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2018.07.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Davalos D, Akassoglou K. Fibrinogen as a key regulator of inflammation in disease. Semin Immunopathol. 2012;34:43–62. doi: 10.1007/s00281-011-0290-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ferrigno D, Buccheri G, Ricca I. Prognostic significance of blood coagulation tests in lung cancer. Eur Respir J. 2001;17:667–673. doi: 10.1183/09031936.01.17406670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Palumbo JS, Kombrinck KW, Drew AF, Grimes TS, Kiser JH, Degen JL, Bugge TH. Fibrinogen is an important determinant of the metastatic potential of circulating tumor cells. Blood. 2000;96:3302–3309. doi: 10.1182/blood.V96.10.3302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Im JH, Fu W, Wang H, Bhatia SK, Hammer DA, Kowalska MA, Muschel RJ. Coagulation facilitates tumor cell spreading in the pulmonary vasculature during early metastatic colony formation. Cancer Res. 2004;64:8613–8619. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yu X, Hu F, Yao Q, Li C, Zhang H, Xue Y. Serum fibrinogen levels are positively correlated with advanced tumor stage and poor survival in patients with gastric cancer undergoing gastrectomy: A large cohort retrospective study. BMC Cancer. 2016;16:480. doi: 10.1186/s12885-016-2510-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Perisanidis C, Psyrri A, Cohen EE, Engelmann J, Heinze G, Perisanidis B, Stift A, Filipits M, Kornek G, Nkenke E. Prognostic role of pretreatment plasma fibrinogen in patients with solid tumors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Treat Rev. 2015;41:960–970. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2015.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pfensig C, Dominik A, Borufka L, Hinz M, Stange J, Eggert M. A new application for albumin dialysis in extracorporeal organ support: Characterization of a putative interaction between human albumin and proinflammatory cytokines IL-6 and TNFα. Artif Organs. 2016;40:397–402. doi: 10.1111/aor.12557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Diakos CI, Charles KA, McMillan DC, Clarke SJ. Cancer-related inflammation and treatment effectiveness. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:e493–e503. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70263-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Paccagnella A, Morassutti I, Rosti G. Nutritional intervention for improving treatment tolerance in cancer patients. Curr Opin Oncol. 2011;23:322–330. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0b013e3283479c66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gupta D, Lis CG. Pretreatment serum albumin as a predictor of cancer survival: A systematic review of the epidemiological literature. Nutr J. 2010;9:69. doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-9-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ouyang X, Dang Y, Zhang F, Huang Q. Low serum albumin correlates with poor survival in gastric cancer patients. Clin Lab. 2018;64:239–245. doi: 10.7754/Clin.Lab.2017.170804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.