Abstract

Purpose

Glaucoma is the second leading cause of blindness worldwide. Recent work suggests that estrogen and the timing of menopause play a role in modulating the risk of developing glaucoma. Menopause is known to cause modest changes in intraocular pressure; yet, whether this change is mediated through the outflow pathway remains unknown. Menopause also affects tissue biomechanical properties throughout the body; however, the impact of menopause on ocular biomechanical properties is not well characterized.

Methods

Here, we simultaneously assessed the impact of menopause on aqueous outflow facility and ocular compliance, as a measure of corneoscleral shell biomechanics. We used young (3–4 months old) and middle-aged (9–10 months old) Brown Norway rats. Menopause was induced by ovariectomy (OVX), and control animals underwent sham surgery, resulting in the following groups: young sham (n = 5), young OVX (n = 6), middle-aged sham (n = 5), and middle-aged OVX (n = 5). Eight weeks postoperatively, we measured outflow facility and ocular compliance.

Results

Menopause resulted in a 34% decrease in outflow facility and a 19% increase in ocular compliance (P = 0.011) in OVX animals compared with sham controls (P = 0.019).

Conclusions

These observations reveal that menopause affects several key physiological factors known to be associated with glaucoma, suggesting that menopause may contribute to an increased risk of glaucoma in women.

Keywords: ocular compliance, outflow facility, menopause, glaucoma, mechanics

Glaucoma is the leading cause of irreversible blindness, and it is estimated that it will affect over 76 million individuals worldwide by 2040.1,2 Glaucoma patients display a typical pattern of visual field loss accompanied by tissue remodeling at the optic nerve head and loss of retinal ganglion cells (RGCs). Recently, it has been proposed that estrogen deficiencies play a role in developing glaucoma in both genders1,3; however, women may have unique risk factors for developing glaucoma involving the estrogen pathway. For example, in women, mutations in the estrogen receptor beta are associated with ocular hypertension.4 Further, women who have experienced early menopause (<45 years of age) have a 2.5-fold increased risk of developing open-angle glaucoma compared with women who enter menopause over 45 years of age.5 Menopause is generally described as the period of time when the ovaries stop producing estrogen and progesterone. Because women represent 59% of the glaucomatous population and the role of menopause in glaucoma is poorly understood,3 the role of menopause as a risk factor for glaucoma merits further study.

Although glaucoma is multifactorial and can occur at any intraocular pressure (IOP), elevated IOP remains a major causal risk factor for developing glaucoma. IOP is biomechanically important in glaucoma, as IOP directly and indirectly mechanically loads the optic nerve head and it is thought that excessive ONH tissue deformation increases glaucomatous risk.6 The response of the eye to IOP depends on both the magnitude of IOP and the intrinsic biomechanical properties of ocular tissues, notably the connective tissues of the ONH and the sclera. Therefore, it is important to understand how menopause affects both IOP and the biomechanical properties of relevant ocular tissues.

Menopause is associated with modest IOP elevations, as IOP in postmenopausal women is 1 to 3 mm Hg higher than in age-matched premenopausal women.7,8 Further, estrogen therapy in postmenopausal women causes a 0.5- to 3-mm Hg decrease in IOP.9–11 Aqueous outflow facility is the major determinant of IOP, and estrogen treatment has been shown to increase outflow facility in female patients12; however, it is unknown whether menopause or age at menopause affects outflow facility. We will address this question here.

The second mechanism by which menopause may influence glaucoma risk is by altering biomechanical properties of ocular tissues, although the impact of menopause on ocular biomechanical properties is relatively unknown. Several studies demonstrated that estrogen and menstruation affect corneal mechanical properties, whereas another in vivo study found no such effect.13–15 Currently, no researcher has examined how menopause or estrogen affects the biomechanical properties of the entire corneoscleral shell. Importantly, there is strong evidence that menopause and estrogen influence biomechanical properties of non-ocular connective tissues, including the vagina, cartilage, and bone.16–19 Therefore, it is likely that menopause also affects biomechanical properties of ocular tissues.

Based on the above evidence, we suspect that estrogen plays a role in regulation of outflow facility and ocular biomechanical properties; thus, we hypothesize that menopause will decrease outflow facility and ocular connective tissue stiffness. We further propose that these changes could synergistically elevate an individual's risk of developing glaucoma.

Methods

Animals

All studies were approved by an Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and conformed to the ARVO Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research. To assess how age and menopausal status alter outflow facility and ocular biomechanical properties, we studied young (3–4 months old) and middle-aged (9–10 months old) Brown Norway rats. Each group was subdivided, with some animals undergoing surgical menopause via ovariectomy (OVX) and the remaining animals undergoing a sham surgery. The sham surgery group accounted for the effects of anesthesia and surgery time while leaving the ovaries intact. This resulted in four separate groups: (1) young sham (n = 8), (2) young OVX (n = 8), (3) middle-aged sham (n = 8), and (4) middle-aged OVX (n = 8). All animals were housed in a 12-hour light/dark cycle with ad libitum access to food and water.

Ovariectomy is the bilateral removal of the ovaries to induce a postmenopausal status. In brief, animals were anesthetized using isoflurane (2%–4% with 100% oxygen) while resting on a heating pad. We made a dorsal incision, and the ovaries were individually identified. In OVX animals, the ovaries were removed, whereas in sham-operated animals the ovaries were exposed and placed back without excision. Wound clips were then used to close the skin, and animals were given an analgesic (buprenorphine 0.05 mg/kg).

Measurement of Outflow Facility and Ocular Biomechanical Properties

Previous work has shown that the mechanical properties of pelvic floor tissues are significantly affected by 8 weeks after OVX.19 Thus, we chose to house the animals for 8 weeks after surgery before euthanizing the animals using CO2. Eyes were then enucleated and we measured aqueous outflow facility and ocular biomechanical properties using the iPerfusion system,20 a custom-designed combination of hardware and software that simultaneously records pressure and fluid flow entering the eye during ocular perfusion. Although the system was originally designed to assess outflow facility,20 it is also capable of measuring ocular compliance.21 All perfusion experiments were begun within 30 minutes of enucleating the eyes.

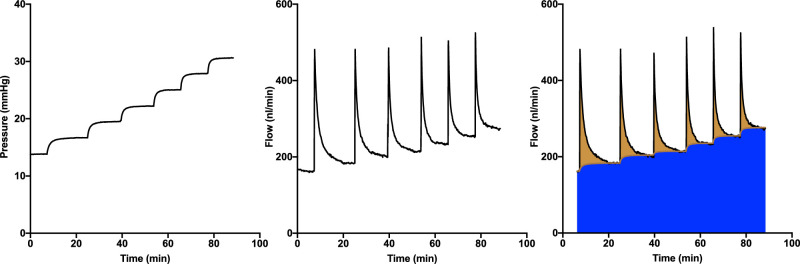

On each day of testing, the pressure and flow sensors in the iPerfusion system were calibrated, and the system compliance was measured. The system compliance was later used to determine ocular compliance by subtracting the system compliance from the total compliance (compliance of the system plus that of the eye). Enucleated eyes were secured on a stage in a heated (37°C) PBS bath, and the anterior chamber was cannulated with a 33-gauge (G) needle (NanoFil; World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL, USA). The eye was perfused with filtered Dulbecco's PBS with 5.5-mM glucose (DBG) and equilibrated at 13 mm Hg until a steady state was reached, typically requiring between 30 and 45 minutes. We then perfused the eye at eight equally divided pressure steps from 12 to 36 mmHg (Fig. 1), ensuring that a steady state was reached at each step based on a previously established threshold.20 We calculated the instantaneous ratio of flow/pressure, then evaluated the slope against time over a moving window of 450 seconds. When the slope was less than 0.1 nl/min/mm Hg/min continuously for a minute, steady state was considered to have been reached.

Figure 1.

Ocular perfusion protocol. (Left) Representative pressure versus time trace during a perfusion. After an acclimatization period of 30 minutes at 13 mm Hg, the pressure is reduced to 12 mm Hg, at which point the perfusion is considered to begin (t = 0). Pressure is then increased in eight steps. The center panel illustrates the corresponding inflow versus time. (Right) Overview of the discrete volume method used to determine ocular volume at each pressure increment. The blue shaded region represents aqueous humor outflow, and the overlying brown shaded region indicates the flow involved in increasing the ocular volume. For each pressure step, the area of this region indicates the total volume increase (system plus eye), from which ocular compliance can be calculated.

In agreement with previous studies in mice,20,22 our preliminary tests confirmed that the Brown Norway rat exhibits zero flow at zero pressure; therefore, we fit the outflow behavior to a power law as previously described:20

| (1) |

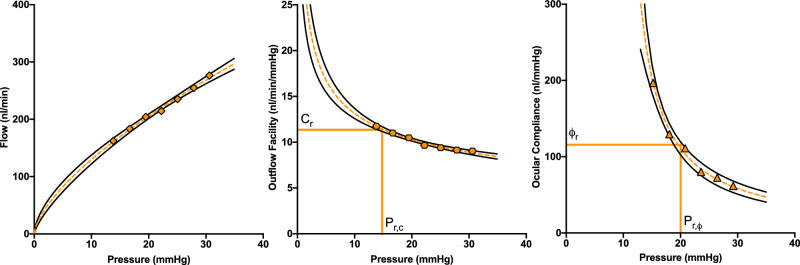

where P is intraocular pressure, Cr is the outflow facility at a reference pressure Pr,c, and β is a fitting parameter characterizing the pressure-dependent change in facility. We chose a reference pressure (Pr,c) of 15 mm Hg (Fig. 2) as a representative physiological pressure drop across the conventional outflow pathway for Brown Norway rats, which have a typical in vivo resting IOP of 20 mm Hg and for which we assumed an episcleral venous pressure of 5 mm Hg.23

Figure 2.

Representative flow, outflow facility, and ocular compliance versus pressure behavior in Brown Norway rats. Flow (left), outflow facility (center), and ocular compliance (right) are functions of pressure. The orange symbols represent measured values at each pressure step, the dashed orange lines are the corresponding fits, and the solid black lines represent the 95% confidence intervals of each fit. The vertical orange lines indicate the reference pressures (15 mm Hg and 20 mm Hg) at which outflow facility (Cr) and ocular compliance (ϕr) were determined.

To assess ocular tissue stiffness, we measured ocular compliance (ϕ), the incremental change in ocular volume per incremental change in IOP, corrected for system compliance as noted above.21 A more compliant eye implies that the corneoscleral shell is less stiff; thus, ocular compliance is an indirect measure of corneoscleral connective tissue properties. The compliance–pressure relationship can be described by a modified Friedenwald equation:

| (2) |

where ϕr is the ocular compliance at a reference pressure Pr,ϕ, which we chose to be 20 mm Hg (Fig. 2), corresponding to the average IOP of the Brown Norway rat.23 The parameter γ is an empirical parameter that accounts for deviation of the compliance–pressure relationship from the Friedenwald model (for which γ = 0).

Ocular compliance was calculated following the previously described discrete volume method,21 in which the compliance is defined as the change in ocular volume for a given change in pressure, ϕ = ∆V/∆P. For a given pressure step j, the ocular compliance can be calculated as

| (3) |

where ∆Pj is the change in pressure between two steps, T is the time at the end of the step, Q is the flow rate (nl/min) measured by the flow sensor, C is the outflow facility (see Equation 1), and ϕs is the system compliance. The term (Q – CP) describes the flow rate of fluid that is accumulating within the eye (i.e., which is expanding the corneoscleral shell); hence, the integral in Equation 3 provides the volume change of the eye (∆Vj) in response to the change in pressure (∆Pj).

As the ocular compliance itself changes during a pressure step, the calculated ocular compliance corresponds to an intraocular pressure (Pϕ,j) that lies between the limits of the pressure for step j and is determined using the mean value theorem:21

| (4) |

Equation 2 can be fit to the acquired Pϕ,j and values to calculate ϕr and γ. However, as γ is not known a priori, an iterative process is applied, which is described elsewhere,21 by initially assuming that γ = 0 to calculate Pϕ,j values with Equation 4, then using these to estimate γ using Equation 2 and repeating.

Statistics

All data analysis and statistics were performed in MATLAB R2016 (MathWorks, Natick, MA, USA). First, we removed outliers using methods described by Iglewicz and Hoaglin.24 In brief, we calculated a z-score based on the median and the median absolute deviation, with values greater than 3.5 indicating an outlier. After excluding poor cannulations and outliers, we obtained the following numbers of animals per group: young sham (n = 5), young OVX (n = 6), middle-aged sham (n = 5), and middle-aged OVX (n = 5). Similar to an earlier approach, a log transformation was applied to outflow facility and ocular compliance, and all datasets were then assessed for normality using an Anderson–Darling test. All fitting parameters (Cr, β, ϕr, and γ) are detailed in the Table and were analyzed using a two-way ANOVA, with age (young vs. middle-aged) and menopausal status (sham vs. OVX) as the two main factors. Based on established statistical methodology,25,26 when the interaction effect between age and menopausal status was not significant in the two-way ANOVA, we report only the main effects of age and of menopause on our outcome measures. Thus, we compare only young versus middle-aged or sham versus OVX. A difference was considered significant at P < 0.05. Comparisons between groups are represented as the percent difference and 95% confidence interval (CI). Data are presented as box-and-whisker plots (lines represent the median, and bars are the minimum to maximum).

Table.

Measured Outcome Parameters for Each Cohort of Rats

| Group, Mean (95% CI) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Young Sham(n = 5) | Young OVX(n = 6) | Middle-Aged Sham(n = 6) | Middle-Aged OVX(n = 5) |

| Outflow facility (nl/min/mm Hg) | 21.2 (11.2 to 40.0) | 12.9 (8.7 to 19.0) | 26.1(23.8 to 28.7) | 19.7 (12.7 to 30.4) |

| β (unitless) | −0.38 (−0.49 to 0.25) | −0.39 (−0.75 to 0.19) | −0.55 (−0.65 to 0.46) | −0.54 (−0.62 to 0.46) |

| Ocular compliance (nl/mm Hg) | 109 (96 to 123) | 131 (111 to 154) | 97 (85 to 111) | 111 (95 to 130) |

| γ (mm Hg) | −8.1 (−11.6 to 4.8) | −6.3 (−9.5 to 3.2) | −5.6 (−7.5 to 3.7) | −6.1 (−9.9 to 2.3) |

The outflow facility at a reference pressure of 15 mm Hg (Cr) and the corresponding nonlinearity parameter (β) describe the outflow facility–pressure relationship. Ocular compliance at a reference pressure of 20 mm Hg (ϕr) and the corresponding nonlinearity parameter (γ) describe the ocular compliance–pressure relationship. Because β and γ take negative values, we report means and confidence intervals.

Results

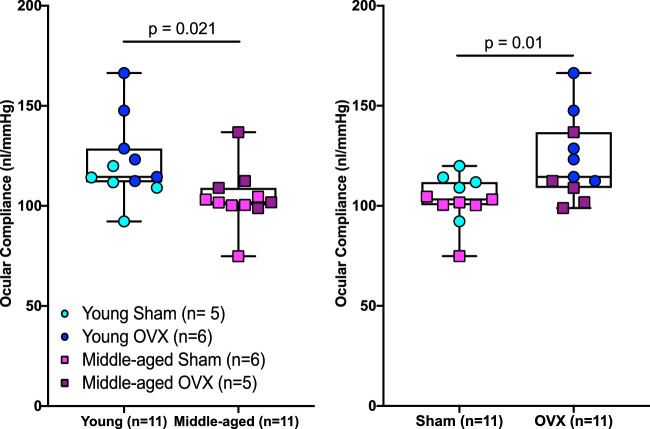

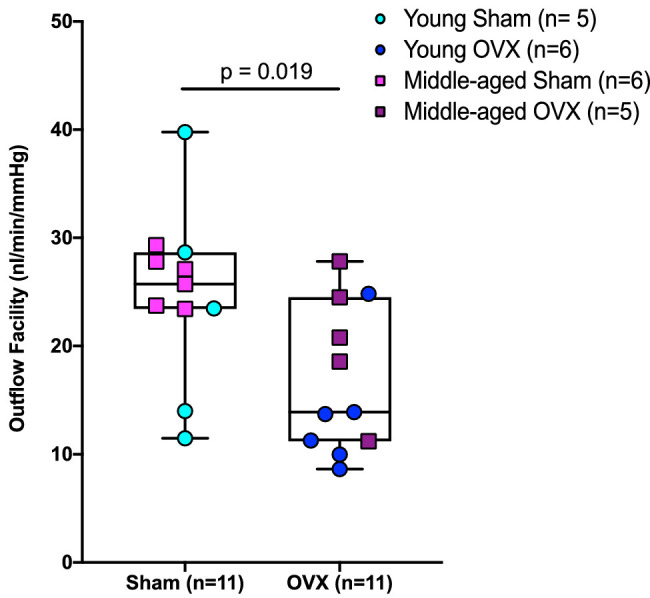

Similar to work published in mice,20 we observed that Equation 1 was able to describe the relationship between outflow facility and pressure in rats (Fig. 2). Although there was no interaction effect of menopause and age on outflow facility (F1,18 = 0.5, P = 0.49), menopausal status affected outflow facility. Specifically, outflow facility was 34% (95% CI, 17–48) lower in OVX animals versus controls (F1,18 = 6.6, P = 0.019) (Fig. 3); however, menopausal status did not impact the nonlinearity of the flow–pressure relationship—that is, the value of the parameter β (F1,18 = 0.02, P = 0.90) (Table). There was also no interaction effect on β between age and menopause (F1,18 = 0.04, P = 0.85); however, middle-aged animals had a 34% (95% CI, 23–44) lower β value versus young animals (F1,18 = 11.03, P = 0.004).

Figure 3.

Menopausal status (OVX) decreased outflow facility in Brown Norway rats. Independent of age, there was a main effect of menopause on outflow facility. Data are pooled across age cohorts for outflow facility to represent the main effect of menopausal status on outflow facility.

All animals displayed a decrease in ocular compliance as pressure increased, as expected. Similar to the situation in mice,21 the modified Friedenwald equation (Equation 2) was able to capture the relationship between ocular compliance and pressure (Fig. 2). Again, we did not find a significant interaction between age and menopause (F1,18 = 0.1, P = 0.68) for ocular compliance; however, OVX animals had a 19% (95% CI, 9–30) increase in ocular compliance (F1,18 = 8.1, P = 0.01) (Fig. 4) compared with sham animals. We also found that ocular compliance was 14% (95% CI, 6–22) lower in middle-aged versus young animals (F1,18 = 6.4, P = 0.021) (Fig. 4). We did not find an interaction effect of menopausal status and age (F1,18 = 1.1, P = 0.31), main effect of menopausal status (F1,18 = 0.32, P = 0.58), or main effect of age (F1,18 = 1.47, P = 0.24) on the nonlinearity parameter γ (Table).

Figure 4.

Age and menopausal status influence ocular biomechanical properties in Brown Norway rats. Middle-aged animals had a significantly lower ocular compliance (left panel) compared to young animals; however, OVX caused a significant increase in ocular compliance (right panel). Data were pooled to show the main effect of age or menopausal status on ocular compliance, as no interaction was found between age and menopause.

Discussion

Our data show that menopausal status decreases aqueous outflow facility and increases the compliance of the corneoscleral shell in a rat model of menopause. These data support our hypothesis and suggest that menopause itself is related to risk factors for developing glaucoma. We also found that approaches developed to describe the nonlinear relationship between outflow facility and ocular compliance with pressure in mice20,21 were well suited to characterize these behaviors in rats.

Our finding that OVX decreased outflow facility is consistent with both the modest elevations in IOP (1–3 mm Hg) measured in postmenopausal women7,9–12 and data suggesting that estrogen therapy increases outflow facility.12

Interestingly, in contrast to previous studies in mice,20 in which β is positive, we found that β was consistently negative, implying a decrease in outflow facility with increasing pressure. Furthermore, although OVX affected β, we did find that age caused a significant increase in the absolute value of β; that is, middle-aged animals exhibited a larger relative reduction in outflow facility with increasing pressure than did younger animals. The reasons for these differences are not clear and deserve further attention in future studies. Nonetheless, these measurements taken using iPerfusion indicate that rats require an assessment of how outflow facility changes as a function of IOP, which we were able to describe using the previously developed equation.20

We also found that OVX increased ocular compliance, which translated to a decrease in stiffness of the corneoscleral shell. The effect of OVX on tissue compliance has been observed in other tissues, including the pelvic floor and arterial tissues.17,19,27,28 The present study and these earlier works indicate that OVX leads to systemic changes in biomechanical properties of connective tissues and could play an important role in the aging process for women. We also found that age caused a significant decrease in ocular compliance, consistent with several other reports showing that the sclera becomes stiffer with age.29–32 This is a normal impact of aging and was important to reproduce within our dataset. The increase in ocular compliance that we measured after OVX is expected to increase optic nerve head tissue deformation caused by a given IOP and thus could increase glaucoma risk,6 although some data on this topic do not support this interpretation.33

Taken together, these results are important because they illustrate that OVX affects multiple components of ocular physiology in ways that may increase the risk of developing glaucoma. Although there are clinical data suggesting that early menopause increases glaucoma risk,3,5 we did not detect an interaction between age and OVX. This may be due in part to our limited sample size and age of these cohorts. Alternatively, the lack of interaction may be because age and OVX have opposite effects on ocular compliance. Specifically, a decrease in ocular stiffness occurring in early menopausal women may increase optic nerve head deformation for a longer period of time (5–7 years) before the natural stiffening that occurs with age counteracts this effect. Such effects would be challenging to study in animal models due to variations in lifespans and circulating hormones but are intriguing and warrant further investigation.

There are limitations to the present study. First, we measured outflow facility in enucleated eyes, which may impact measurements, especially the nonlinearity of the relationship between outflow facility and pressure (β). The measured value of β may be an artifact of the species, euthanasia technique, or enucleation. As noted earlier, previous reports in mice have reported a positive value of β.20,21 Nonetheless, it is still intriguing that, under matched testing conditions, we found significant differences in the flow–pressure relationship between OVX and sham eyes. Previous reports using the iPerfusion system in mice measured an outflow facility of 5.4 nl/min/mm Hg,20 and we expect a higher outflow facility for the larger rat eye. Indeed, our pooled sham groups had an outflow facility of 23.8 nl/min/mm Hg, which agrees with the outflow facility (23 nl/min/mm Hg) reported by Ficarrotta et al.34 using a different approach in male Brown Norway rats, supporting the interpretation of our overall results.

A second limitation is related to our compliance measurements. We measured compliance of the entire corneoscleral shell and thus do not know how OVX independently impacted the cornea and sclera. Future tests directly characterizing the impact of OVX on the cornea and sclera should be performed, as scleral properties are thought to be more relevant in glaucoma. In addition, based on the finding that menopausal status impacts ocular compliance, future studies focused on assessing the extracellular matrix content and organization of the sclera are warranted. Another limitation is the use of OVX to model menopause. Here, we have shown that menopause affects outflow facility and ocular compliance; however, it should be noted that menopause has various effects throughout the body and that differences in age, animal strain, and duration of menopause may influence its impact on biomechanical properties of tissues. These questions are outside the scope of the present study, but it is important to acknowledge the potential for menopause to have a range of effects due to multiple factors. OVX also causes a rapid decline in circulating hormones, and although this can occur in women, a majority of women undergo a perimenopausal state (i.e., a gradual loss of circulating hormones during the transition into menopause). However, in an animal study, the ability to control the timing and duration of menopause facilitates the interpretation of results and provides the ability to assess how age at menopause may be related to risk factors for glaucoma.

Accepting these limitations, we believe these results are important. They highlight that menopausal status affects outflow facility and ocular biomechanical properties. Specifically, we have illustrated that menopausal status is a unique factor to consider in the development of glaucoma in women.

Acknowledgments

Supported by a Department of Veterans Affairs Rehabilitation Research & Development (RR&D) Service Career Development Award (RX002342A [AJF]) and a Department of Veterans Affairs RR&D Service Senior Research Career Scientist Award (RX003134 [MTP]), as well as by the Georgia Research Alliance (CRE), Royal Academy of Engineering (JMS) and the National Institutes of Health (EY022359 [DRO]). The opinions expressed herein do not necessarily reflect those of the Department of Veterans Affairs, the National Institutes of Health, or the U.S. Government.

Disclosure: A.J. Feola, None; J.M. Sherwood, None; M.T. Pardue, None; D.R. Overby, None; C.R. Ethier, None

References

- 1. Quigley HA, Broman AT. The number of people with glaucoma worldwide in 2010 and 2020. Br J Ophthalmol. 2006; 90: 262–267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wang W, He M, Li Z, Huang W. Epidemiological variations and trends in health burden of glaucoma worldwide. Acta Ophthalmol. 2019; 97: e349–e355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Vajaranant TS, Pasquale LR. Estrogen deficiency accelerates aging of the optic nerve. Menopause. 2012; 19: 942–947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mabuchi F, Sakurada Y, Kashiwagi K, Yamagata Z, Iijima H, Tsukahara S. Estrogen receptor beta gene polymorphism and intraocular pressure elevation in female patients with primary open-angle glaucoma. Am J Ophthalmol. 2010; 149: 826–830.e1–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hulsman CA, Westendorp IC, Ramrattan RS, et al.. Is open-angle glaucoma associated with early menopause? The Rotterdam Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2001; 154: 138–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Burgoyne CF. A biomechanical paradigm for axonal insult within the optic nerve head in aging and glaucoma. Exp Eye Res. 2011; 93: 120–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Panchami, SR, Shenoy JP, Shivakumar J, Kole SB. Postmenopausal intraocular pressure changes in South Indian females. J Clin Diagn Res. 2013; 7: 1322–1324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Qureshi IA. Ocular hypertensive effect of menopause with and without systemic hypertension. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1996; 75: 266–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Vajaranant TS, Maki PM, Pasquale LR, Lee A, Kim H, Haan MN. Effects of hormone therapy on intraocular pressure: the Women's Health Initiative-Sight Exam study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2016; 165: 115–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sator MO, Joura EA, Frigo P, et al.. Hormone replacement therapy and intraocular pressure. Maturitas. 1997; 28: 55–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Altintas O, Caglar Y, Yuksel N, Demirci A, Karabas L. The effects of menopause and hormone replacement therapy on quality and quantity of tear, intraocular pressure and ocular blood flow. Ophthalmologica. 2004; 218: 120–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Treister G, Mannor S. Intraocular pressure and outflow facility. Effect of estrogen and combined estrogen-progestin treatment in normal human eyes. Arch Ophthalmol. 1970; 83: 311–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Goldich Y, Barkana Y, Pras E, et al.. Variations in corneal biomechanical parameters and central corneal thickness during the menstrual cycle. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2011; 37: 1507–1511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Spoerl E, Zubaty V, Raiskup-Wolf F, Pillunat LE. Oestrogen-induced changes in biomechanics in the cornea as a possible reason for keratectasia. Br J Ophthalmol. 2007; 91: 1547–1550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Seymenoglu G, Baser EF, Zerdeci N, Gulhan C. Corneal biomechanical properties during the menstrual cycle. Curr Eye Res. 2011; 36: 399–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Feola A, Duerr R, Moalli P, Abramowitch S. Changes in the rheological behavior of the vagina in women with pelvic organ prolapse. Int Urogynecol J. 2013; 24: 1221–1227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rasanen T, Messner K. Articular cartilage compressive stiffness following oophorectomy or treatment with 17beta-estradiol in young postpubertal rabbits. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1999; 78: 357–362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chen L, Zeng T, Xia W, Li H, Zhou M. The effect of estrogen on the restoration of bone mass and bone quality in ovariectomized rats. J Tongji Med Univ. 2000; 20: 283–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Moalli PA, Debes KM, Meyn LA, Howden NS, Abramowitch SD. Hormones restore biomechanical properties of the vagina and supportive tissues after surgical menopause in young rats. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008; 199: e161–e168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sherwood JM, Reina-Torres E, Bertrand J, Rowe B, Overby DR. Measurement of outflow facility using iPerfusion. PLoS One. 2016; 11: e0150694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sherwood JM, Boazak EM, Feola AJ, Parker K, Ethier CR, Overby DR. Measurement of ocular compliance using iPerfusion. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2019; 7: 276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Madekurozwa M, Reina-Torres E, Overby DR, Sherwood JM. Direct measurement of pressure-independent aqueous humour flow using iPerfusion. Exp Eye Res. 2017; 162: 129–138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Moore CG, Johnson EC, Morrison JC. Circadian rhythm of intraocular pressure in the rat. Curr Eye Res. 1996; 15: 185–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Iglewicz B, Hoaglin D. How to Detect and Handle Outliers. Milwaukee, WI: American Society for Quality Control, Statistics Division; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sheskin DJ. Handbook of Parametric and Nonparametric Statistical Procedures. Third ed. Boca Raton, FL: Chapman & Hall/CRC Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Motulsky H. Intuitive Biostatistics. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Cox RH, Fischer GM. Effects of sex hormones on the passive mechanical properties of rat carotid artery. Blood Vessels. 1978; 15: 266–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Zhang Y, Stewart KG, Davidge ST. Estrogen replacement reduces age-associated remodeling in rat mesenteric arteries. Hypertension. 2000; 36: 970–974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Coudrillier B, Pijanka J, Jefferys J, et al.. Effects of age and diabetes on scleral stiffness. J Biomech Eng. 2015; 137: 0710071–07100710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Grytz R, Fazio MA, Libertiaux V, et al.. Age- and race-related differences in human scleral material properties. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2014; 55: 8163–8172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Fazio MA, Grytz R, Morris JS, et al.. Age-related changes in human peripapillary scleral strain. Biomech Model Mechanobiol. 2014; 13: 551–563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Girard MJ, Suh JK, Bottlang M, Burgoyne CF, Downs JC. Scleral biomechanics in the aging monkey eye. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009; 50: 5226–5237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kimball EC, Nguyen C, Steinhart MR, et al.. Experimental scleral cross-linking increases glaucoma damage in a mouse model. Exp Eye Res. 2014; 128: 129–140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ficarrotta KR, Bello SA, Mohamed YH, Passaglia CL. Aqueous humor dynamics of the Brown-Norway rat. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2018; 59: 2529–2537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]