Abstract

Introduction

To examine gender differences in associations between mental health comorbidity and adverse childhood experiences (ACE) among adults with DSM-5 lifetime opioid use disorders (OUD).

Methods

In 2018, we analyzed 2012–13 nationally-representative data from 388 women and 390 men with OUD (heroin, prescription opioid misuse). Using weighted multinomial logistic regression, we examined factors associated with mental health comorbidity, tested a gender-by-childhood-adversity interaction term, and calculated predicted probabilities, controlling for covariates.

Results

Among adults with OUD, women are more likely than men to have comorbid mood or anxiety disorders (odds ratio [95% CI] 1.72 [1.20, 2.48]), and less likely to have conduct disorders. More women than men have prescription OUD (3.72 [2.24, 6.17]), and fewer have heroin use disorder (0.39 [0.27, 0.57]). Among both genders, ACE prevalence is high (>80%) and more than 40% are exposed to ≥3 types of ACE. Women more than men are exposed to childhood sexual abuse (4.22 [2.72, 6.56]) and emotional neglect (1.84 [1.20, 2.81]). Comorbid mood or anxiety disorders are associated with female gender (1.73 [1.18, 2.55]) and exposure to ≥3 types of ACE (3.71 [2.02, 6.85]), controlling for covariates. Moreover, exposure to more ACE elevates risk for comorbid mood or anxiety disorders more among women than men.

Conclusion

Among adults with OUD, ACE alters the gender gap in risk for comorbid mood or anxiety disorders. Using gender-tailored methods to address the harmful effects ACE on the mental health of individuals with OUD may help to prevent and ameliorate the current opioid epidemic.

Keywords: Gender differences, Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE), DSM-5 opioid use disorder, DSM-5 comorbid mood and anxiety disorders, National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC-III)

Introduction

The opioid epidemic is a national public health emergency, responsible for extraordinary numbers of accidental injuries, infectious diseases, and premature deaths.1–3 This has resulted in a historic shortening of American life expectancy.4, 5 Women with opioid use disorders (OUD) are especially vulnerable to these adverse outcomes. Among women aged 30–64 years, the drug overdose death rate increased 260% from 1999 to 2017, with a notable increase in deaths involving synthetic opioids (1,643%) and heroin (915%).6 Recent research using cross-sectional national survey data from 2007–2014 has shown that, although men have higher rates of heroin use and misuse of prescription opioids, women are increasing heroin use at a faster rate than men.7 At the same time, misuse of prescription opioids has been decreasing among both men and women more recently, but the rate of decrease is slower among women, leading to a convergence in the rate of prescription opioid misuse between women and men.7 There are known gender differences in the causes and consequences of opioid and other types of substance use disorders, and yet the particular variations are incompletely understood.8, 9

A decade ago, Grella and colleagues established that women with OUD have more pervasive and severe mental health problems than their male counterparts.10 Subsequent research found a co-occurring mental health condition is a critical risk factor for adverse outcomes, particularly among women with opioid or other substance use disorders.11, 12 More recently, research has pointed to the importance of examining the relationship of adverse childhood experiences (ACE) before age 18 on the development of subsequent health-related problems in adulthood. Exposure to physical or sexual abuse, and other types of childhood adversity, is associated with numerous poor health outcomes across the life span,13 including mental health disorders,14 alcohol and drug use disorders,15–17 and premature death.18 In turn, ACE also increases risk for earlier onset of risk behaviors, including criminal behavior and involvement with the criminal justice system and sexual risk behaviors.19–22

Regarding OUD, ACE are associated with earlier opioid use, ongoing injection opioid use, and more lifetime opioid overdose experiences.23 These behaviors often predict a more severe and persistent OUD over the life course.11 Importantly, much of the life course research on OUD was conducted prior to the current opioid epidemic.11 Thus, much of what we know about associations between ACE and OUD are mostly based on samples of individuals with heroin use disorder, which may not pertain to individuals with nonmedical prescription opioid use disorder. More recent emerging evidence suggests ACE elevates women’s odds for OUD (including heroin and nonmedical prescription opioid use disorder) and other substance use disorders to levels similar to or exceeding levels among men.16, 17 Furthermore, women are differentially exposed to certain types of ACE, i.e., sexual abuse, compared to men and therefore have worse outcomes.16, 17 Findings suggest ACE may cause or contribute to OUD differently for women and men. A remaining question is whether there are gender differences among adults with OUD in the relationships between ACE and mental health co-morbidity. Research could reveal gender-specific differences in the effects of ACE, which could be used to tailor OUD prevention and intervention initiatives. We address these knowledge gaps by examining gender differences in the relationship between ACE and mental health co-morbidity among a nationally representative sample of adults with OUD; we hypothesize that there is a greater association between ACE and mental health co-morbidity for women when compared to men. Moreover, we examine these relationships with a population dataset, concurrent with the dramatic increasing prevalence of heroin use and prescription opioid misuse.24–26 This survey data enables us to generate revised prevalence estimates of mental health conditions among women and men with OUD within the context of the current opioid crisis.

Methods

Parent study design

Cross-sectional data were obtained from the 2012–13 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC-III).27, 28 Detailed elsewhere,27 the NESARC-III target population comprised noninstitutionalized U.S. residents 18 years and older of households and selected group quarters. Trained interviewers performed informed consent and collected data using face-to-face computer-assisted personal interviews.27 The total sample size was 36,309. The household response rate was 72%; person-level response rate, 84%; and overall response rate, 60.1%, comparable with current national surveys.29, 30 Data were weighted to adjust for oversampling and nonresponse, and to represent the U.S. noninstitutionalized adult population, accounting for sociodemographic distributions per the 2012 American Community Survey.27 NESARC-III data have provided nationwide epidemiologic information on heroin and other opioid use.31, 32

Present study sample

NESARC-III administered the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism DSM-5 version of the Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule (AUDADIS-5) to separately measure lifetime alcohol and drug-specific types of substance use disorders, including heroin and nonmedical prescription opioid use disorder (defined as opiate painkillers not including heroin or methadone).33, 34 AUDADIS-5 diagnoses have fair-to-excellent reliability and validity. 35, 31

The present study focused on all individuals in NESARC-III with a lifetime heroin or nonmedical prescription opioid use disorder (unweighted n=778) totaling 388 women and 390 men. This sample represented 2.28% of the total (weighted) NESARC-III general population sample. Among this sample, 9.9% (weighted) had only a heroin use disorder (unweighted n=90), 79.1% (weighted) had only a nonmedical prescription opioid use disorder (unweighted n=620), and 11.0% (weighted) had both (unweighted n=68). The sample was 45.9% women and 54.1% men (weighted). In this sample, 47.0%, was aged 25–44, 33.0% was 45–64, 15.4% was 18–24, and 4.7% was 65 and older. Regarding race and ethnicity, the sample, was 77.8% White, 9.1% Hispanic, 9.1% Black, and 3.9% another race/ethnicity (e.g., Asian, Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, American Indian, Alaska Native). About half of the sample, 49.9%, had some college education or higher, 32.5% had a GED or high school diploma, and 17.6% had less than a high school education. Many were married (46.7%), 24.6% were widowed/divorced/separated, and 58.7% had never married. Fewer women than men had never married (25.0% vs. 31.8%, respectively) and more women than men were widowed/divorced/separated (29.1% vs. 20.8%, respectively; p<0.05). Most, 77.4%, lived in an urban area, with 35.2% living in the South, 24.0% the West, 21.2% the Midwest, and 19.5% the Northeast.

Measures

The dependent variable was the presence of a comorbid mental health disorder. NESARC-III used the AUDADIS-5 to measure DSM-5 diagnoses of: (1) mood disorders, including major depression, dysthymia, mania, and hypomania; (2) anxiety disorders, including panic disorder with and without agoraphobia, social phobia, specific phobia, and generalized anxiety disorder; (3) personality disorders, including borderline, conduct, schizotypal, and antisocial; and (4) post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Per DSM-5 criteria, all mood and anxiety disorder diagnoses met the clinical significance criterion and excluded substance and illness-induced cases. Reliability and validity of AUDADIS-5 assessment of mental health disorders are fair to good.33,36, 37 We examined the prevalence by gender of each type of mental health disorder. Per prior research,10 we defined comorbid mental health disorder as any lifetime DSM-5 mood or anxiety disorder.

A key independent variable was childhood adversity. NESARC-III assessed abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction before age 18 using items from the Conflict Tactics Scale38 and the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire.39 We considered the following 11 childhood adversity types, defined per the Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) study40, 41 and related epidemiological research16, 42 (Appendix A: Table 2): (1–3) abuse: emotional, physical, sexual; (4–5) neglect: emotional, physical; and (6–11) household dysfunction: mother treated violently and parental health (substance abuse, mental illness, incarceration, suicidal ideation). We created an indicator variable for individuals’ experience of adversity and a variable for the total number of different types of ACE (range: 0–11). Individuals who were missing data on all 11 types of ACE were coded as missing (n=2). Next, given the known dose-response association between behavioral health conditions and 1–2 experiences of ACE versus ≥3,20, 26 we followed methods used in prior NESARC studies16, 17, 43, 44 and created three mutually exclusive total-adversity categories: 0, 1–2, ≥3.

Table 2.

ACE Exposures among Adults with Lifetime OUD in NESARC-III, by Gendera

| Women (%) (n=388) |

Men (%) (n=390) |

Total (%) (n=778) |

Odds Ratio (95% CI) b | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of childhood adversity | ||||

| Any abuse, % | 56.6 | 48.7 | 52.3 | 1.38 (1.00, 1.90)* |

| Physical abuse | 36.0 | 39.7 | 38.0 | 0.85 (0.61, 1.20) |

| Sexual abuse | 36.3 | 11.9 | 22.9 | 4.22 (2.72, 6.56)*** |

| Emotional abuse | 32.7 | 27.0 | 29.6 | 1.31 (0.94, 1.83) |

| Any neglect, % | 54.8 | 59.8 | 57.5 | 0.81 (0.60, 1.09) |

| Physical neglect | 50.2 | 56.8 | 53.8 | 0.77 (0.58, 1.02) |

| Emotional neglect | 23.4 | 14.3 | 18.5 | 1.84 (1.20, 2.81)** |

| Any household dysfunction, % | 63.1 | 60.0 | 61.4 | 1.14 (0.81, 1.60) |

| Parental problematic substance use | 52.5 | 53.1 | 52.8 | 0.98 (0.69, 1.38) |

| Battered mom | 27.3 | 24.1 | 25.6 | 1.18 (0.79, 1.77) |

| Parental incarceration | 16.1 | 24.4 | 20.6 | 0.60 (0.36, 0.98)* |

| Parental mental illness | 11.2 | 10.8 | 11.0 | 1.04 (0.63, 1.72) |

| Parental suicide attempt | 8.4 | 9.3 | 8.9 | 0.89 (0.53, 1.49) |

| Parental suicide completion | 2.3 | 2.9 | 2.6 | 0.79 (0.25, 2.46) |

| Any childhood adversity, % | 85.0 | 80.7 | 82.7 | 1.36 (0.84, 2.21) |

| No. different types of childhood adversity, % | ||||

| 0 | 15.1 | 20.0 | 17.8 | ref |

| 1–2 | 38.2 | 33.7 | 35.8 | 0.75 (0.47, 2.20) |

| >=3 | 46.6 | 46.3 | 46.4 | 1.13 (0.77, 1.64) |

ACE, Adverse Childhood Experiences

NESARC-III, National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions-III

OUD, Opioid Use Disorder

Boldface indicates statistical significance (*p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001)

Weighted percentages and weighted odds ratios.

Women=1, Men = 0

Socio-demographic characteristics investigated were gender, age, race/ethnicity, and educational attainment.

Statistical Analysis

We examined by gender the prevalence of lifetime mental health disorders, lifetime opioid and other substance use disorders, and ACE. The strength of these associations was assessed in logistic regression models with gender entered as a dummy variable (women=1, men=0). Next, we used logistic regression to assess associations between any comorbid mood or anxiety disorder, ACE, and gender, controlling for covariates.45 We tested a “gender-by-childhood-adversity” interaction term. We used the moderation model to test for group differences with pair-wise comparisons and to calculate predicted probabilities with 95% confidence intervals for the outcome in relation to ACE. We used a two-tailed significance level at p <0.05. All analyses were weighted and conducted using STATA 15 with commands to account for complex survey design (StataCorp LP, 2014).

Results

Mood and Anxiety Disorders

Table 1 shows the prevalence of lifetime mood and anxiety disorders among adults with OUD by gender, and associated odds ratios (ORs; women vs. men) derived from the logistic regression models. Altogether, 68.4% of the study sample met criteria for at least one non-substance use disorder, 58.7% had at least one mood disorder, and 41.7% had at least one anxiety disorder. The most prevalent disorder was major depression, with 50.1% of the sample meeting diagnostic criteria.

Table 1.

Mental Health Disorders among Adults with Lifetime Opioid Use Disorders in NESARC-III, by Gendera

| Women (%) (n=388) |

Men (%) (n=390) |

Total (%) (n=778) |

Odds Ratio (95% CI) b | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any mood or anxiety disorder (Axis I) | 74.7 | 63.1 | 68.4 | 1.72 (1.20, 2.48)** |

| Any mood disorder | 63.7 | 54.5 | 58.7 | 1.46 (1.03, 2.09)* |

| Major depression (non-hierarchical) | 59.6 | 42.0 | 50.1 | 2.04 (1.42, 2.94)*** |

| Dysthymia (non-hierarchical) | 25.1 | 19.9 | 22.3 | 1.35 (0.92, 1.99) |

| Manic disorder (non-hierarchical) | 10.9 | 12.2 | 11.6 | 0.87 (0.47, 1.63) |

| Hypomanic disorder (non-hierarchical) | 2.2 | 3.3 | 2.8 | 0.68 (0.26, 1.76) |

| Any anxiety disorder | 54.6 | 30.8 | 41.7 | 2.71 (1.83, 4.02)*** |

| Panic disorder w/o agoraphobia | 15.7 | 11.3 | 13.3 | 1.46 (0.85, 2.50) |

| Panic disorder w/agoraphobia | 10.0 | 2.1 | 5.7 | 5.28 (1.88, 14.85)** |

| Social phobia | 16.2 | 9.0 | 12.3 | 1.96 (1.04, 3.69)* |

| Specific phobia | 20.3 | 9.2 | 14.3 | 2.52 (1.53, 4.14)*** |

| Generalized anxiety disorder | 30.0 | 12.9 | 20.8 | 2.90 (1.78, 4.72)*** |

| Any personality disorder | 55.1 | 57.0 | 56.1 | 0.93 (0.61, 1.40) |

| Schizotypal personality disorder (at least 1 criterion soc/occ) c | 24.7 | 30.4 | 27.8 | 0.75 (0.51, 1.10) |

| Schizotypal personality disorder (at least 2 criteria soc/occ) c | 19.4 | 22.3 | 21.0 | 0.83 (0.57, 1.23) |

| Borderline personality disorder (at least 1 criterion soc/occ) c | 49.1 | 42.6 | 45.6 | 1.30 (0.92, 1.84) |

| Borderline personality disorder (at least 2 criteria soc/occ) c | 45.5 | 39.3 | 42.2 | 1.29 (0.90, 1.84) |

| Conduct disorder without soc/occc | 15.9 | 33.5 | 25.4 | 0.37 (0.25, 0.56)*** |

| Conduct disorder with soc/occc | 11.1 | 24.7 | 18.5 | 0.38 (0.25, 0.58)*** |

| Antisocial personality disorder without soc/occ | 15.4 | 32.2 | 24.5 | 0.38 (0.26, 0.57)*** |

| Antisocial personality disorder with soc/occ | 10.8 | 24.7 | 18.3 | 0.37 (0.24, 0.57) |

NESARC-III, National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions-III

Boldface indicates statistical significance (*p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001)

All disorders reflect DSM-5 criteria.

Weighted percentages and weighted odds ratios.

Women=1, Men = 0

Diagnoses are provided with and without the requirement for the distress/social-occupational dysfunction criterion.

Women had approximately 1.5 the odds as men for having a lifetime mood disorder (1.46 [95% CI 1.03, 2.09]) and were twice as likely as men to have major depression (OR 2.04 [95% CI 1.42, 2.94]). There was no difference between women and men, however, in the odds of having dysthymia, manic disorder, and hypomanic disorder. Women had more than twice the odds of men for having an anxiety disorder (OR 2.71 [95% CI 1.83, 4.02]), with significantly greater odds of having panic disorder with agoraphobia (OR 5.28 [95% CI 1.88, 14.85]), social phobia (OR 1.96 [95% CI 1.04, 3.69]), specific phobia (OR 2.52 [95% CI 1.53, 4.14]), and generalized anxiety disorder (OR 2.90 [95% CI 1.78, 4.72]).

Personality Disorders

More than half of the sample, 56.1%, met criteria for at least one personality disorder (see Table 1). Women were about a third as likely as men to have conduct disorder and antisocial personality disorder. There was no gender difference in the odds of having schizotypal or borderline personality disorder. Overall, there was no gender difference in the likelihood of having at least one of the personality disorders that was assessed.

Alcohol, Tobacco, and Drug-Specific Use Disorders

We examined prevalence rates by gender for specific substance use disorders in the lifetime (Appendix B). A majority of the sample, 90.1%, had nonmedical prescription opioid use disorder, and 20.9% had heroin use disorder. More women than men had nonmedical prescription opioid use disorder (OR 3.72 [95% CI 2.24, 6.17]), and fewer had heroin use disorder (OR 0.39 [95% CI 0.27, 0.57]) (Appendix B).

Other than opioids, the most prevalent types of substance use disorder were alcohol and tobacco, with ~75% of the sample meeting disorder criteria for each of these substances, followed by marijuana (36.5%), cocaine (27.0%), sedatives (26.6%), stimulants (22.5%), hallucinogens (11.9%), club drugs (9.6%), and inhalants/solvents (4.4%). Overall, 82.9% had an alcohol or drug use disorder in addition to an OUD. Results from the logistic regression models showed women were less likely than men to have alcohol, marijuana, cocaine, and hallucinogen use disorders; there was no gender difference in the odds of having any of the remaining SUD disorders. Adults with both a lifetime OUD and also a lifetime mood or anxiety disorder were significantly more likely to meet lifetime criteria for disorders related to tobacco (OR 1.84), alcohol (OR 2.31), marijuana (OR 1.59), and sedatives (OR 1.76) (see Appendix C). This was the case even when gender was included as a covariate, indicating the relationship between lifetime mental health disorders and other substance use disorders among adults with OUD is independent of gender.

Childhood Adversity

Most women and men with OUD (82.7%) had been exposed to some type of childhood adversity; about 46% had experienced ≥3 types of ACE (Table 2). More than half of women and men reported childhood physical neglect or having had parents with problematic substance use, making each of these the most commonly reported specific type of ACE. By gender, more women than men had experienced childhood sexual abuse (OR 4.22 [95% CI 2.72, 6.56]) and childhood emotional neglect (OR 1.84 [95% CI 1.20, 2.81]), and fewer women had experienced childhood parental incarceration (OR 0.60 [95% CI 0.36, 0.98]).

Predictors of Mood and Anxiety Disorders

Weighted regression model results from a main effects model (Table 3, Model 1) indicated among adults with OUD, the presence of a comorbid mental health disorder was positively associated with being female (OR 1.73 [95% CI 1.18, 2.55]) and exposure to 3 or more types of ACE (OR 3.71 [95% CI 2.02, 6.85]); it was negatively associated with being age 65 or older (OR 0.24 [95% CI 0.08, 0.74]) and Hispanic race/ethnicity (OR .41 [95% CI 0.21, 0.78]).

Table 3.

ACE and Comorbid Mental Health Disorders among Adults with Lifetime OUD in NESARC-III, by Gender (n=776)

| Model 1. Main effects | Model 2. Moderated | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds Ratio | 95 % CI | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | |

| Women (ref: men) | 1.73*** | 1.18, 2.55 | 1.20 | 0.53, 2.68 |

| Age (ref: 18–24) | ||||

| 25–44 | 0.63 | 0.31, 1.31 | 0.61 | 0.30, 1.23 |

| 45–64 | 0.51 | 0.24, 1.12 | 0.50 | 0.24, 1.06 |

| 65 and older | 0.24** | 0.08, 0.74 | 0.24** | 0.09, 0.69 |

| Race/ethnicity (ref: White) | ||||

| Hispanic | 0.41** | 0.21, 0.78 | 0.40** | 0.20, 0.79 |

| Black | 0.83 | 0.43, 1.59 | 0.86 | 0.46, 1.63 |

| Other (AAPI, AINA) | 1.32 | 0.49, 3.58 | 1.31 | 0.48, 3.56 |

| Educational attainment (less than GED/HS) | ||||

| GED | 0.96 | 0.48, 1.95 | 1.01 | 0.50, 2.03 |

| High School | 0.92 | 0.53, 1.61 | 0.92 | 0.51, 1.65 |

| College | 1.29 | 0.83, 2.02 | 1.30 | 0.82, 2.04 |

| Post-baccalaureate | 2.11 | 0.81, 5.53 | 2.18 | 0.84, 5.68 |

| No. different types of childhood adversity (ref: 0) | ||||

| 1–2 | 1.52 | 0.82, 2.83 | 1.66 | 0.73, 3.75 |

| ≥3 | 3.71*** | 2.02, 6.85 | 2.47* | 1.14, 5.32 |

| Interaction term (ref: men & 0 childhood adversity) | -- | -- | Omnibus F-test = .003 | |

| Women & 1–2 childhood adversity exposures | 0.90 | 0.33, 2.46 | ||

| Women & ≥3 childhood adversity exposures | 3.32* | 1.25, 8.83 | ||

ACE, Adverse Childhood Experiences

NESARC-III, National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions-III

OUD, Opioid Use Disorder

Boldface indicates statistical significance (*p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001)

Weighted data

Comorbid=1, Non-comorbid = 0.

Comorbid mental health disorder is defined as any DSM 5 mood or anxiety disorder.

2 individuals were omitted due to missing data.

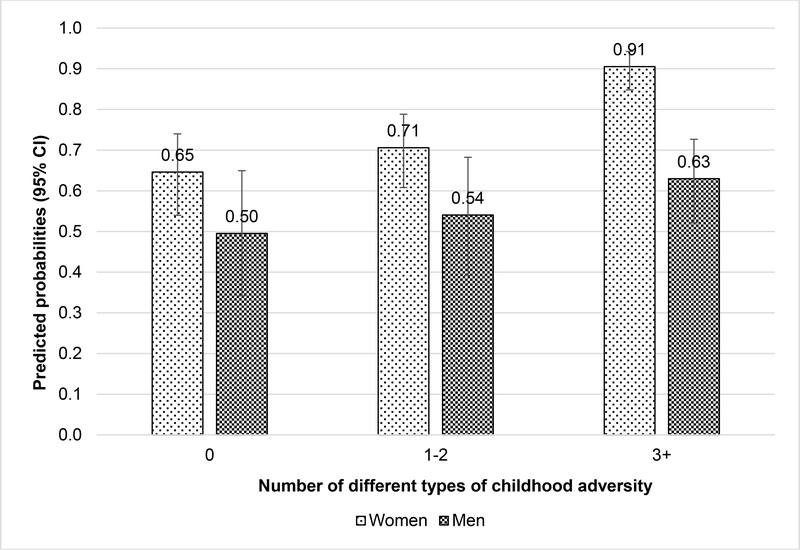

In a multiplicative model, and controlling for covariates, the “gender by childhood adversity” term was statistically significant at p < 0.003 (omnibus F test) (Table 3, Model 2). Given that there was evidence for moderation, we conducted pair-wise comparisons to test which specific contrasts were statistically significant. Figure 1 shows predicted probabilities with 95% of confidence intervals by gender for presence of a comorbid mental health condition in relation to ACE. A visual inspection suggested women with OUD mostly exhibited higher predicted probability for a comorbid mental health condition than men with OUD. However, this gender difference in predicted probability for a comorbid mental health condition was statistically significant only among individuals who had experienced 3 or more types of ACE. Specifically, among individuals with 3 or more types of ACE, the predicted probability for a mental health condition was higher among women (0.91) than among men (0.63), representing a difference of 0.28 that was significant at p < 0.001. In contrast, the gender differences in predicted probabilities for a mental health condition among individuals with 0 or 1–2 types ACE were not statistically significant.

Figure 1.

Gendered comorbid mental health disorders probabilities by ACE count, adults with lifetime OUD in NESARC-III (n = 776)

ACE, Adverse Childhood Experiences

NESARC-III, National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions-III

OUD, Opioid Use Disorder

Comorbid mental health disorder is defined as any DSM 5 mood or anxiety disorder.

Based on results from Table 3, Model 2.

Discussion

Among adults with opioid use disorder (OUD), women are more likely than men to have comorbid mood or anxiety disorders and less likely to have conduct disorders. Findings are remarkably consistent with Grella and colleagues’ previous report.10 Although the relationship between gender and comorbidity of OUD and mental health disorders is consistent, the overall gender difference in prevalence of OUD is decreasing, so women comprise a larger proportion of those in the population with OUD relative to men. We also found more women than men have prescription OUD, and fewer have heroin use disorder. In the current opioid epidemic, women are at similar46 or greater risk than men for the misuse of prescription opioids.47, 48

Our findings implicate the need to develop and implement gender-sensitive prevention and intervention programs. Overall, the rates of treatment for non-medical prescription opioid use remain low, with less than one third of men and women with non-medical prescription opioid use disorders ever receiving treatment.46 Policy interventions to address the opioid epidemic have largely concentrated on disseminating interventions for opioid-overdose prevention and reversal, improving treatment for OUD, increasing MAT capacity, improving treatment of chronic pain, and increasing prescription monitoring49–51 Additionally, more attention is needed to address the high rates of co-morbid mental health disorders among the population with OUD and how both gender and comorbidity may influence the outcomes of these various interventions.

We also found more than 80% of both women and men with OUD have experienced some type of ACE; nearly half have been exposed to three or more types of ACE. In comparison, among women and men who do not have OUD, about 58% of each gender have experienced some type of ACE; about 19% have been exposed to three or more types of ACE (analysis not shown). Findings point to the much greater extent to which individuals with OUD have been exposed to ACE compared to peers in the general population who do not have OUD. We also found that comorbid mood or anxiety disorders among adults with OUD was associated with female gender and ACE, controlling for other factors. Moreover, with more ACE the gender gap in risk for comorbid mood or anxiety disorders widened. Consistent with similar research, women with OUD are also more adversely affected by these experiences. Specifically, among adults with OUD, exposure to more ACE elevates risk for comorbid mood or anxiety disorders for women more compared to men.

Collectively, these findings suggest using gender-tailored methods to address the harmful effects of ACE on the mental health of individuals with OUD may help to prevent and ameliorate the nation’s current opioid epidemic. Tailoring could include greater integration of trauma-specific care principles52 into treatment of women with OUD and more aggressive efforts to diagnose and treat comorbid mood and anxiety disorders. Pediatricians and other health care providers have already begun to take an active role in setting an agenda to prevent ACE53 and disrupt its intergenerational effects.54–58 While efforts are needed for all children at risk, these results suggest gender-tailored messages may also be important.

More broadly, the strong association observed between exposure to adverse childhood experiences and OUD points to the need to address the larger context in which childhood abuse and trauma may be a vector for later development of opioid use disorders, as well as other psychiatric and substance use disorders.59 This argues for the adoption of a public health framework for combating the opioid crisis, which includes effective clinical interventions as well as strategies that address the larger structural determinants that underlie the development of these disorders.60

Limitations and Strengths

Findings must be considered in light of several limitations. OUD, mental health disorders, and ACE were self-reported and may be impacted by biases (social desirability, recall). These biases may have been more salient among men, given their reluctance to disclose childhood interpersonal abuse experiences, suggesting our results may underestimate the relationship between men’s experiences of ACE and risk for mental health disorders.61 Prior studies that have examined the validity of retrospective recall of ACE have concluded these reports may be biased but are sufficiently valid for epidemiological research, particularly when ACE is well-defined61–63 as was done by NESARC. ACE was measured as a count variable. Future research would be strengthened by considering the typologies of ACE and how experiences group together by gender. The cross-sectional design precluded determining temporal sequencing of experiences, making causal inferences unfeasible. We did not explore associations with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) or adulthood trauma. In this sample, women were more than twice as likely as men to have PTSD (35.5% of women, 17.4% of men; OR 2.61 [95% CI 1.74, 3.91]). PTSD is highly comorbid with other psychiatric disorders,64 warranting future research. Finally, additional analysis indicated that among individuals with only nonmedical prescription opioid use disorder (and no heroin use disorder), more women than men had any mood or anxiety disorder (74.2% vs. 62.8%; p<0.001); among individuals with only heroin use disorder (and no nonmedical prescription opioid use disorder), 70.7% of women and 65.9% of men had any mood or anxiety disorder, a difference that was not statistically significant. Differences by gender in exposure to any childhood adversity were not statistically significant among individuals with only nonmedical prescription opioid use disorder (women: 85.4%, men: 81.9%) and among individuals with only heroin use disorder (women: 88.1%, men: 76.1%). Due to sample size limilations, we did not present results separately for heroin use disorder and nonmedical prescription opioid use disorders as has been done by previous studies using NESARC data,32,34 constituting an area for future research.

Regarding study strengths, we utilized nationally representative data that includes standardized assessments of OUD, mental health, and ACE. Data is critical for assessing our nation’s patterns and prevalence of these experiences and health conditions; these data provide generalizable knowledge on early life factors associated with mental health among adults with OUD. Additionally, the deliberate overrepresentation of young adults, racial/ethnic minorities, and group home residents, ensures the sample includes populations and a life-course period that are associated with OUD development. Finally, women have been underrepresented in research on OUD. Our findings demonstrate women form a large percentage of persons with OUD (46% in our data). Thus, a key strength is that we explore by gender the potential etiological origins of OUD and mental health conditions.

Conclusions

Among U.S. adults with OUD, ACE alters the gender gap in risk for comorbid mood or anxiety disorders. Using gender-tailored methods to address the harmful effects of ACE on the mental health of individuals with OUD may help to prevent and ameliorate the nation’s current opioid epidemic.

Statements

This study was approved by the appropriate ethics committee and has therefore been performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments.

Highlights.

80% of adults with opioid use disorder (OUD) have had adverse childhood experiences (ACE).

Among adults with OUD, ACE increases risks for mood or anxiety disorders.

ACE alters the gender gap in risk for comorbid mood or anxiety disorders.

Gender-tailored responses to ACE may prevent and ameliorate the opioid epidemic.

Acknowledgments

Role of Funding Sources

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Dr. Evans is supported by The Greenwall Foundation, the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) UG3 DA0044830-02S1 and UG1DA050067-01, and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), Center for Substance Abuse Treatment (CSAT) Grant No. 1H79T1081387-01.

Appendices

Appendix A. Operationalization of key variables

Alcohol and drug use disorders (AUD, DUD)

Lifetime AUD diagnoses required at least 2 of the 11 DSM-5 criteria in the past year or prior to the past year. 35 Diagnoses before the past year required clustering of at least 2 criteria within a 1-year period. 35 Substance-specific DUD included nonheroin opioid and heroin, and also sedative or tranquilizer, cannabis, amphetamine, cocaine, club drug (e.g., ecstasy, ketamine), hallucinogen, and solvent/inhalant. 31 Consistent with DSM-5, each lifetime diagnoses required at least 2 of the 11 criteria arising from use of the same substance in the past year or prior to the past year. 31 Diagnoses before the past year required clustering of at least 2 criteria for the same drug within a 1-year period. 31

Childhood adversity

NESARC-III assessed adverse childhood events occurring before age 18 using questions that were a subset of items from the Conflict Tactics Scale38 and the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire. 39 Respondents were asked to respond to all questions pertaining to abuse or neglect (except emotional neglect) on a five-point scale (never, almost never, sometimes, fairly often, or very often). Emotional neglect questions employed an alternative five-point scale of never true, rarely true, sometimes true, often true, or very often true. All questions pertaining to general household dysfunction required yes/no responding (except questions regarding having a battered mother, which used the same scale as for the items on abuse or neglect) (Table 2).

We considered 11 types of childhood adversity, which we defined to be consistent with definitions employed in the Adverse Childhood Experiences study 15, 40 and epidemiological research on childhood adversity. 16, 42

Physical abuse was defined as a response of “sometimes” or greater to either question when asked how often a parent or other adult living in the respondent’s home (1) pushed, grabbed, shoved, slapped, or hit the respondent; or (2) hit the respondent so hard it left marks or bruises, or caused an injury.

Emotional abuse was identified as a response of “fairly often” or “very often” to any question when asked how often a parent or other adult living in the respondent’s home (1) swore at, insulted, or said hurtful things to the respondent; (2) threatened to hit or throw something at the respondent (but did not do it); or (3) acted in any other way that made the respondent afraid he/she would be physically hurt or injured.

Sexual abuse was examined using four questions that examined the occurrence of sexual touching or fondling, attempted intercourse, or actual intercourse by any adult or other person when the respondent did not want the act to occur or was too young to understand what was happening. Any response other than “never” on any of the questions was coded as sexual abuse.

Physical neglect was defined as any response other than “never” to five questions that asked about experiences of being made to do difficult or dangerous chores, being left unsupervised when too young to care for self or going without needed clothing, school supplies, food, or medical treatment.

Emotional neglect was defined by five questions asking whether respondents felt a part of a close-knit family or whether anyone in the family of origin made the respondent feel special, wanted the respondent to succeed, believed in the respondent, or provided strength and support. Following prior research, the five items were reverse-scored and summed; scores of 15 or greater were coded as emotional neglect. 15, 40, 42

Parental substance abuse was a form of household dysfunction that was assessed with two questions asking whether a parent or other adult living in the home had a problem with alcohol or drugs. A response of “yes” to either question was defined as parental substance abuse.

To characterize the history of having a battered mother, respondents were asked whether the respondent’s father, stepfather, foster/adoptive father, or mother’s boyfriend had ever done any of the following to the respondent’s mother, stepmother, foster/adoptive mother, or father’s girlfriend: (1) pushed, grabbed, slapped, or threw something at her; (2) kicked, bit, hit with a fist, or hit her with something hard; (3) repeatedly hit her for at least a few minutes; or (4) threatened to use or actually used a knife or gun on her. Any response of “sometimes” or greater for questions 1 or 2, or any response except “never” for questions 3 or 4, was defined as having a battered mother.

For the other measures of household dysfunction, respondents were asked to answer with either “yes” or “no” whether a parent or other adult in the home (1) went to jail or prison; (2) was treated or hospitalized for mental illness; (3–4) attempted or actually committed suicide. A response of “yes” to any of these questions was coded as household dysfunction.

Appendix Table A.1.

Operationalization of childhood adversity

| Event | # of items | Wording of each item | Response categories | Occurrence of childhood adversity is indicated by… |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abuse | ||||

| Physical abuse | 2 | How often a parent or other adult living in the respondent’s home (1) Pushed, grabbed, shoved, slapped, or hit the respondent; or (2) Hit the respondent so hard it left marks or bruises, or caused an injury |

5-point scale 1 = never 2 = almost never, 3 = sometimes 4 = fairly often 5 = very often |

“Sometimes” or greater to either item |

| Sexual abuse | 4 | Occurrence of (1) Sexual touching or fondling (2) Attempted intercourse, or (3) Actual intercourse by any adult or (4) Other person when the respondent did not want the act to occur or was too young to understand what was happening |

5-point scale 1 = never 2 = almost never, 3 = sometimes 4 = fairly often 5 = very often |

Any response other than “never” on any item |

| Emotional abuse | 3 | How often a parent or other adult living in the respondent’s home (1) Swore at, insulted, or said hurtful things to the respondent (2) Threatened to hit or throw something at the respondent (but did not do it); or (3) Acted in any other way that made the respondent afraid he/she would be physically hurt or injured |

5-point scale 1 = never 2 = almost never, 3 = sometimes 4 = fairly often 5 = very often |

A response of “fairly often” or “very often” to any item |

| Neglect | ||||

| Physical neglect | 5 | Respondents’ experiences of (1) Being left unsupervised when too young to care for themselves or (2) being made to do dangerous or difficult chores, or (3–5) Going without needed clothing, school supplies, food, or medical treatment |

5-point scale 1 = never 2 = almost never, 3 = sometimes 4 = fairly often 5 = very often |

Any response other than “never” to any item |

| Emotional neglect | 5 | Whether the respondent (1) Felt a part of a close-knit family or whether anyone in the respondent’s family of origin (2) Made the respondent feel special (3) wanted the respondent to succeed (4) Believed in the respondent, or (5) Provided strength and support |

5 point scale 1 = never 2 = rarely 3 = sometimes 4 = often 5 = very often |

Reverse-scored and summed; indicated by scores ≥15 15, 40–42 |

| Household dysfunction | ||||

| Battered mom | 4 | Whether the respondent’s father, stepfather, foster/adoptive father, or mother’s boyfriend had ever done any of the following to the respondent’s mother, stepmother, foster/adoptive mother, or father’s girlfriend (1) Pushed, grabbed, slapped, or threw something at her (2) Kicked, bit, hit with a fist, or hit her with something hard (3) Repeatedly hit her for at least a few minutes (4) Threatened to use or actually used a knife or gun on her |

5-point scale 1 = never 2 = almost never, 3 = sometimes 4 = fairly often 5 = very often |

Any response of “sometimes” or greater for questions 1 or 2, or any response except “never” for questions 3 or 4 |

| Parental | ||||

| Substance use | 2 | Whether (1) a parent or (2) other adult living in the home had a problem with alcohol or drugs | 0 = No 1 = Yes |

Response of “yes” to either item |

| Incarceration | 1 | Parent or other adult in the home went to jail or prison | 0 = No 1 = Yes |

Yes |

| Mental illness | 1 | Parent or other adult in the home was treated or hospitalized for a mental illness | 0 = No 1 = Yes |

Yes |

| Suicide attempt | 1 | Parent or other adult in the home attempted suicide | 0 = No 1 = Yes |

Yes |

| Suicide | 1 | Parent or other adult in the home actually committed suicide | 0 = No 1 = Yes |

Yes |

Appendix B.

Lifetime Other Substance Use Disorders among Adults with Lifetime OUD in NESARC-III, by Gendera

| Women (%) (n=388) |

Men (%) (n=390) |

Total (%) (n=778) |

Odds Ratio (95% CI) b | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Opioids | 95.6 | 85.4 | 90.1 | 3.72 (2.24, 6.17)*** |

| Heroin | 13.0 | 27.6 | 20.9 | 0.39 (0.27, 0.57)*** |

| Tobacco | 70.8 | 77.2 | 74.2 | 0.72 (0.49, 1.05) |

| Alcohol | 70.0 | 80.0 | 75.2 | 0.60 (0.39, 0.90)* |

| Marijuana | 30.6 | 41.6 | 36.5 | 0.62 (0.42, 0.92)* |

| Cocaine | 20.4 | 32.6 | 27.0 | 0.53 (0.35, 0.80)** |

| Sedatives | 29.8 | 23.9 | 26.6 | 1.36 (0.97, 1.89) |

| Stimulants | 20.2 | 24.5 | 22.5 | 0.78 (0.51, 1.18) |

| Hallucinogen | 7.4 | 15.8 | 11.9 | 0.42 (0.22, 0.81)** |

| Club drugs | 6.8 | 11.9 | 9.6 | 0.54 (0.29, 1.02) |

| Inhalants/solvents | 2.7 | 5.9 | 4.4 | 0.44 (0.17, 1.13) |

| Other substances | 2.0 | 2.4 | 2.2 | 0.82 (0.31, 2.19) |

| Any other substancec | 77.8 | 87.2 | 82.9 | 0.51 (0.32, 0.82)** |

NESARC-III, National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions- III

OUD, Opioid Use Disorder

p<0.05

p<0.01

p<0.001

All disorders reflect DSM-5 criteria.

Weighted percentages and weighted odds ratios.

Women=1, Men = 0

Any of the above substances, except for tobacco, in addition to heroin/opioids

Appendix C.

Lifetime Other Substance Use Disorders among Adults with Lifetime Opioid Use Disorders in NESARC-III, by Comorbid Mental Health Statusa

| Comorbid (%) (n=530) |

Non-comorbid (%) (n=248) |

Total (%) (n=778) |

Odds Ratio (95% CI)b | Odds Ratio Adjusted for Gender (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Opioids | 90.4 | 89.7 | 90.1 | 1.08 (0.59, 1.99) | 0.93 (0.49, 1.75) |

| Heroin | 20.7 | 21.3 | 20.9 | 0.97 (0.64, 1.47) | 1.09 (0.71, 1.67) |

| Tobacco | 77.7 | 66.8 | 74.2 | 1.73 (1.17, 2.57)** | 1.84 (1.21, 2.79)** |

| Alcohol | 79.8 | 65.4 | 75.2 | 2.09 (1.35, 3.24)*** | 2.31 (1.46, 3.65)*** |

| Marijuana | 39.3 | 30.6 | 36.5 | 1.47 (0.98, 2.21) | 1.59 (1.07, 2.35)* |

| Cocaine | 28.1 | 24.8 | 27.0 | 1.19 (0.74, 1.91) | 1.30 (0.81, 2.08) |

| Sedatives | 30.1 | 19.2 | 26.6 | 1.81 (1.21, 2.73)** | 1.76 (1.17, 2.64)** |

| Stimulants | 23.2 | 21.2 | 22.5 | 1.12 (0.69, 1.82) | 1.16 (0.71, 1.90) |

| Hallucinogen | 12.3 | 11.3 | 11.9 | 1.10 (0.56, 2.17) | 1.23 (0.63, 2.43) |

| Club drugs | 10.2 | 8.2 | 9.6 | 1.27 (0.62, 2.62) | 1.39 (0.68, 2.82) |

| Inhalants/solvents | 5.0 | 3.2 | 4.4 | 1.60 (0.59, 4.29) | 1.78 (0.66, 4.78) |

| Other substances | 2.3 | 1.9 | 2.2 | 1.20 (0.33, 4.43) | 1.24 (0.33, 4.67) |

| Any other substancec | 87.0 | 74.1 | 82.9 | 2.33 (1.42, 3.84)*** | 2.67 (1.59, 4.47)*** |

National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions-III

p<0.05

p<0.01

p<0.001

All disorders reflect DSM-5 criteria.

Weighted percentages and weighted odds ratios.

Comorbid=1, Non-comorbid = 0. Comorbid is defined as any mood or anxiety disorder.

Any of the above substances except for tobacco, in addition to heroin/opioids

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Hedegaard H, Minino AM, Warner M. Drug overdose deaths in the United States, 1999–2017. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db329-h.pdf. NCHS Data Brief 2018;329:1–8. Accessed May 13, 2019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hedegaard H, Warner M, Minino AM. Drug overdose deaths in the United States, 1999–2016. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db294.htm. NCHS Data Brief. 2017;294:1–8. Accessed May 13, 2019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Substance Abuse Mental Health Services. Office of the Surgeon G. In: Facing Addiction in America: The Surgeon General’s report on alcohol, drugs, and health. https://addiction.surgeongeneral.gov/sites/default/files/OC_SpotlightOnOpioids.pdf Published 2016 Accessed May 13, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kochanek KD, et al. Mortality in the United States, 2016. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db293.htm. NCHS Data Brief. 2017;293: 1–8. Accessed May 13, 2019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Murphy SL, Xu J, Kochanek KD, Curtin SC, Arias E. Deaths: Final Data for 2015. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr66/nvsr66_06.pdf. Natl Vital Stat Rep 2017;66(6):1–75. Accessed May 13, 2019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.VanHouten JP, Rudd RA, Ballesteros MF, Mack KA. Drug overdose deaths among women aged 30–64 years - United States, 1999–2017. MMWR. 2019;68(1):1–5. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6801a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marsh JC, Park K, Lin YA, Bersamira C. Gender differences in trends for heroin use and nonmedical prescription opioid use, 2007–2014. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2018;87:79–85. 10.1016/j.jsat.2018.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Office of Women’s Health. Final Report: opioid use, misuse, and overdose in women. https://www.womenshealth.gov/files/documents/final-report-opioid-508.pdf. Published July 19, 2017. Accessed 5/09/2019

- 9.Meyer JP, Isaacs K, El-Shahawy O, Burlew AK, Wechsberg W. Research on women with substance use disorders: reviewing progress and developing a research and implementation roadmap. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019;197:158–163. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.01.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grella CE, Karno MP, Warda US, Niv N, Moore AA. Gender and comorbidity among individuals with opioid use disorders in the NESARC Study. Addict Behav 2009;34(6–7):498–504. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.addbeh.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hser YI, Evans E, Grella C, Ling W, Anglin D. Long-term course of opioid addiction. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2015; 23(2):76–89. 10.1097/HRP.0000000000000052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Greenfield SF, Brooks AJ, Gordon SM, et al. Substance abuse treatment entry, retention, and outcome in women: a review of the literature. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;86(1):1–21. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.05.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hughes K, Bellis MA, Hardcastle KA, et al. The effect of multiple adverse childhood experiences on health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2017;2(8):e356–e366. 10.1016/S2468-2667(17)30118-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Green JG, McLaughlin KA, Berglund PA, et al. Childhood adversities and adult psychiatric disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication I: associations with first onset of DSM-IV disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(2):113–123. https://dx.doi.org/10.1001%2Farchgenpsychiatry.2009.186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cavanaugh CE, Petras H, Martins SS. Gender-specific profiles of adverse childhood experiences, past year mental and substance use disorders, and their associations among a national sample of adults in the United States. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2015;50(8):1257–1266. 10.1007/s00127-015-1024-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Evans EA, Grella CE, Upchurch DM. Gender differences in the effects of childhood adversity on alcohol, drug, and polysubstance-related disorders. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2017;52(7):901–912. 10.1007/s00127-017-1355-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Evans EA, Upchurch DM, Simpson T, Hamilton AB, Hoggatt KJ. Differences by veteran/civilian status and gender in associations between childhood adversity and alcohol and drug use disorders. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2018;53(4):421–435. 10.1007/s00127-017-1463-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Anda RF, Dong M, Brown DW, et al. The relationship of adverse childhood experiences to a history of premature death of family members. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:106 10.1186/1471-2458-9-106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Campbell JA, Walker RJ, Egede LE. Associations between adverse childhood experiences, high-risk behaviors, and morbidity in adulthood. Am J Prev Med. 2016;50(3):344–352. 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.07.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fox BH, Perez N, Cass E, Baglivio MT, Epps N. Trauma changes everything: examining the relationship between adverse childhood experiences and serious, violent and chronic juvenile offenders. Child Abuse Negl. 2015;46:163–173. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marshall B, Spohr SA, Taxman FS, Walters ST. The effect of childhood household dysfunction on future HIV risk among probationers. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2017;28(2):754–769. 10.1353/hpu.2017.0072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stinson JD, Quinn MA, Levenson JS. The impact of trauma on the onset of mental health symptoms, aggression, and criminal behavior in an inpatient psychiatric sample. Child Abuse Negl. 2016;61:13–22. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2016.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stein MD, Conti MT, Kenney S, et al. Adverse childhood experience effects on opioid use initiation, injection drug use, and overdose among persons with opioid use disorder. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2017;179:325–329. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Compton WM, Jones CM, Baldwin GT. Relationship between nonmedical prescription-opioid use and heroin use. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(2):154–163. 10.1056/NEJMra1508490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dart RC, Surratt HL, Cicero TJ, et al. Trends in opioid analgesic abuse and mortality in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(3):241–248. 10.1056/NEJMsa1406143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jones CM. Heroin use and heroin use risk behaviors among nonmedical users of prescription opioid pain relievers - United States, 2002–2004 and 2008–2010. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;132(1–2):95–100. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grant BF, Amsbary M, Chu A. Source and accuracy statement: National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions-III (NESARC-III). Rockville, MD: National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hasin DS, Grant BF. The National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC) waves 1 and 2: review and summary of findings. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2015;50(11):1609–1640. 10.1007/s00127-015-1088-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Detailed Tables. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; Rockville, MD: 2016. Accessed May 13, 2019 https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-MethodSummDefsHTML-2015/NSDUH-MethodSummDefsHTML-2015/NSDUH-MethodSummDefs-2015.htm [Google Scholar]

- 30.Blackwell DL, Lucas JW, Clarke TC. Summary Health Statistics for U.S. Adults: National Health Interview Survey, 2012; National Center for Health Statistics. Vital Health Stat Published 2014;10(260). Accessed May 13, 2019 https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/series/sr_10/sr10_260.pdf [PubMed]

- 31.Grant BF, Saha TD, Ruan WJ, et al. Epidemiology of DSM-5 drug use disorder: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions-III. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;73(1):39–47. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.2132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Martins SS, Sarvet A, Santaella-Tenorio J, Saha T, Grant BF, Hasin DS. Changes in US lifetime heroin use and heroin use disorder: prevalence from the 2001–2002 to 2012–2013 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(5):445–455. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.0113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Grant BF, Goldstein RB, Smith SM, et al. The Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule-5 (AUDADIS-5): reliability of substance use and psychiatric disorder modules in a general population sample. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015;148:27–33. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.11.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Saha TD, Kerridge BT, Goldstein RB, et al. Nonmedical prescription opioid use and DSM-5 nonmedical prescription opioid use disorder in the United States. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016;77(6):772–780. 10.4088/JCP.15m10386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Grant BF, Goldstein RB, Saha TD, et al. Epidemiology of DSM-5 Alcohol Use Disorder: Results From the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions III. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(8):757–766. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.0584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hasin DS, Sarvet AL, Meyers JL, et al. Epidemiology of adult DSM-5 major depressive disorder and its specifiers in the United States. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75(4):336–346. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.4602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hasin DS, Shmulewitz D, Stohl M, et al. Procedural validity of the AUDADIS-5 depression, anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder modules: substance abusers and others in the general population. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015;152:246–256. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.03.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Straus MA, Hamby SL, Boney-McCoy S, Sugarman DB. The Revised Conflict Tactics Scales (CTS2): development and preliminary psychometric data. J. Fam. Issues. 1996;17(3):283–316. 10.1177/019251396017003001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bernstein DP, Fink L, Handelsman L, et al. Initial reliability and validity of a new retrospective measure of child abuse and neglect. Am. J. Psychiatry. 1994;151(8):1132–1136. 10.1176/ajp.151.8.1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dube SR, Felitti VJ, Dong M, Chapman DP, Giles WH, Anda RF. Childhood abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction and the risk of illicit drug use: The Adverse Childhood Experiences Study. Pediatrics. 2003;111(3):564–572. 10.1542/peds.111.3.564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dong M, Anda RF, Dube SR, Giles WH, Felitti VJ. The relationship of exposure to childhood sexual abuse to other forms of abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction during childhood. Child Abuse Negl. 2003;27(6):625–639. 10.1016/S0145-2134(03)00105-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Afifi TO, Henriksen CA, Asmundson GJ, Sareen J. Childhood maltreatment and substance use disorders among men and women in a nationally representative sample. Can J Psychiatry. 2012;57(11):677–686. 10.1177/070674371205701105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McLaughlin KA, Conron KJ, Koenen KC, Gilman SE. Childhood adversity, adult stressful life events, and risk of past-year psychiatric disorder: a test of the stress sensitization hypothesis in a population-based sample of adults. Psychol Med. 2010;40(10):1647–1658. 10.1017/S0033291709992121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Myers B, McLaughlin KA, Wang S, Blanco C, Stein DJ. Associations between childhood adversity, adult stressful life events, and past-year drug use disorders in the National Epidemiological Study of Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC). Psychol Addict Behav. 2014; 28(4):1117–1126. 10.1037/a0037459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hernán MA, Robins JM. Causal Inference. Boca Raton: Chapman & Hall/CRC, forthcoming; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kerridge BT, Saha TD, Chou SP, et al. Gender and nonmedical prescription opioid use and DSM-5 nonmedical prescription opioid use disorder: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions - III. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015;156:47–56. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.08.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hemsing N, Greaves L, Poole N, Schmidt R. Misuse of prescription opioid medication among women: a scoping review. Pain Res. Manag. 2016;1754195 10.1155/2016/1754195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Serdarevic M, Striley CW, Cottler LB. Sex differences in prescription opioid use. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2017;30(4):238–246. 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Blanco C, Volkow ND. Management of opioid use disorder in the USA: present status and future directions. Lancet. 2019; 393(10182):1760–1772. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)33078-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Volkow ND, Frieden TR, Hyde PS, Cha SS. Medication-assisted therapies--tackling the opioid-overdose epidemic. N Engl J Med. 2014; 370(22):2063–2066. 10.1056/NEJMp1402780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Volkow ND, Collins FS. The role of science in addressing the opioid crisis. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(4):391–394. 10.1056/NEJMsr1706626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fareed A, Eilender P, Haber M, Bremner J, Whitfield N, Drexler K (2013) Comorbid posttraumatic stress disorder and opiate addiction: a literature review. Journal of Addictive Diseases. 2013; 32(2): 168–179. 10.1080/10550887.2013.795467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bethell CD, Solloway MR, Guinosso S, et al. Prioritizing possibilities for child and family health: an agenda to address adverse childhood experiences and foster the social and emotional roots of well-being in pediatrics. Acad. Pediatr. 2017;17(7s):S36–s50. 10.1016/j.acap.2017.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Le-Scherban F, Wang X, Boyle-Steed KH, Pachter LM. Intergenerational associations of parent adverse childhood experiences and child health outcomes. Pediatrics. 2018;141(6). 10.1542/peds.2017-4274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Letourneau N, Dewey D, Kaplan BJ, et al. Intergenerational transmission of adverse childhood experiences via maternal depression and anxiety and moderation by child sex. J Dev Orig Health Dis. 2019;10(1):88–99. 10.1017/S2040174418000648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.McDonnell CG, Valentino K. Intergenerational Effects of Childhood Trauma: Evaluating Pathways Among Maternal ACEs, Perinatal Depressive Symptoms, and Infant Outcomes. Child Maltreatment 2016;21(4):317–326. 10.1177/1077559516659556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.McDonald SW, Madigan S, Racine N, Benzies K, Tomfohr L, Tough S. Maternal adverse childhood experiences, mental health, and child behaviour at age 3: The All Our Families Community Cohort Study. Prev Med. 2019;118:286–294. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2018.11.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sun J, Patel F, Rose-Jacobs R, Frank DA, Black MM, Chilton M. Mothers’ adverse childhood experiences and their young children’s development. Am J Prev Med. 2017;53(6):882–891. 10.1016/j.amepre.2017.07.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dasgupta N, Beletsky L, Ciccarone D. Opioid crisis: no easy fix to its social and economic determinants. Am J Public Health. 2018; 108(2): 182–186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Saloner B, McGinty EE, Beletsky L, Bluthenthal R, Beyrer C, Botticelli M, Sherman SG. A public health strategy for the opioid crisis. Public Health Reports. 2018; 133 (1_supp l), 24S–34S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hardt J, Rutter M. Validity of adult retrospective reports of adverse childhood experiences: review of the evidence. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry. 2004;45(2):260–273. 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00218.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Brewin CR, Andrews B, Gotlib IH. Psychopathology and early experience: a reappraisal of retrospective reports. Psychol Bull 1993;113(1):82–98. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/0033-2909.113.1.82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Patten SB, Wilkes TC, Williams JV, et al. Retrospective and prospectively assessed childhood adversity in association with major depression, alcohol consumption and painful conditions. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2015;24(2):158–165. 10.1017/S2045796014000018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Smith SM, Goldstein RB, Grant BF. The association between post-traumatic stress disorder and lifetime DSM-5 psychiatric disorders among veterans: data from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions-III (NESARC-III). J. Psychiatr. Res. 2016;82:16–22. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2016.06.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]