Graphical abstract

Keywords: Bank efficiency, Globalization, Foreign bank entry, International expansion, Home-country effect, Host-country effect

Abstract

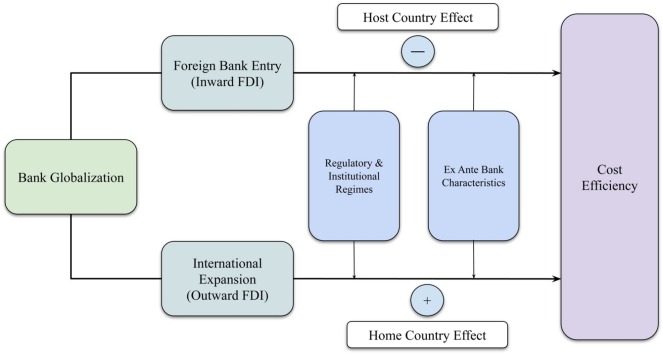

Analyzing 126 countries for 1995–2013, we investigate the link between bank globalization and efficiency from the perspective of both host and home countries. We find strong and consistent evidence that foreign bank entry is associated with lower efficiency in host countries (host-country effect), while foreign expansion in the banking sector improves the efficiency of banks at home (home-country effect). We further observe that the effect of bank globalization is dependent on the regulatory and institutional regimes of the respective host (home) countries. Specifically, stringent activity restrictions, tight supervision, fewer limitations on foreign banks, lower market entry barriers, and less government interference all help mitigate the efficiency loss from foreign bank entry. Less supervision power, multiple supervisors, more restrictions on foreign banks, and a competitive banking market are all conducive to the higher efficiency gain of incumbent domestic banks from the respective country’s outward investments in the banking sector. Moreover, we find that the adverse impact on efficiency from foreign bank presence is less pronounced for less risky, more profitable, and larger banks, while banks that are more efficient, more profitable, taking on more risk, and/or smaller gain more efficiency from their country’s foreign expansion.

1. Introduction

Globalization in banking has been part of the inherent international economic and financial linkages in the past few decades. The collapse of the Soviet Union and liberalization in Latin America have provided opportunities for foreign banks to enter countries in Central and Eastern Europe and Latin America in the 1990s. In recent years, further liberalization of financial services in other parts of the world, such as Asia, has prompted large banking institutions to invest in countries such as China and India. In tandem with the growing trend of bank globalization, research on globalization in banking has thrived as well. Many studies have examined the effects of bank globalization at the macro level. Some investigate the role banks play in the international transmission of shocks and co-movements of business cycles (Cetorelli and Goldberg, 2012; Morgan and Strahan, 2003; Peek and Rosengren, 1997). Others try to determine how financial sector foreign direct investment (FDI) affects host country employment (Bank for International Settlements, 2006), economic growth (Borensztein et al., 1998), or institutional development (Mishkin, 2007). Most of these studies show that bank globalization has significant impacts on the respective macroeconomic variables.

Another strand of the literature inspects the effects of bank globalization at the micro or bank level, particularly whether bank globalization helps improve bank performance, often gauged by profitability, costs, the net interest margin, or other performance measures. Most of these studies focus on banks in a particular economy or geographic region. Barajas et al. (2000) compare the performance of foreign-owned versus domestic banks in Columbia in the 1990s and find that financial liberalization generally had a beneficial impact on bank behavior in Colombia, by increasing competition, lowering intermediation costs, and improving loan quality. Using bank-specific data for a range of Latin American countries over the latter half of the 1990s, Crystal et al. (2001) investigate the effects of foreign bank entry and find that the financial strength ratings of local banks acquired by foreign entities generally experience slight improvements relative to their domestic counterparts. Sturm and Williams (2004) compare the efficiency of foreign-owned banks operating in Australia with domestic banks during the post-deregulation period 1988–2001. They find that foreign banks are, on average, more input efficient than domestic banks, mainly due to superior scale efficiency. Unite and Sullivan (2001) use accounting data for Philippine commercial banks over the period from 1990 through 1998 to investigate how the relaxation of foreign entry regulations affects domestic banks. They find foreign bank entry leads to declines in interest rate spreads and operating expenses. Yin et al. (2013) examine the technical efficiency of 171 Chinese banks over 1999–2010 and find bank efficiency to have an upward trend after China’s entry to the World Trade Organization in 2001. Similarly, Zhu and Yang (2016) investigate the risk-taking behavior of 123 banks in China from 2000 to 2013 and find that foreign acquisition has helped reduce risk taking by state-owned banks, and this effect is particularly significant for banks that are controlled by central or local governments.

Among the cross-country studies on bank globalization, Yin (2019) and Wu et al. (2017) both find that foreign bank entry increases bank risk, with datasets on 129 countries and 35 emerging countries, respectively. Chen et al. (2017) observe that foreign-owned banks take on more risk than their domestic counterparts in 32 emerging countries. Using data from 80 countries for 1988–1995, Claessens et al. (2001) find that foreign banks have higher profits than domestic banks in developing countries, but the opposite is true for developed countries, suggesting that the increased presence of foreign banks is associated with a reduction in profitability and margins for domestic banks. Ghosh (2016) uses a dataset of 169 nations spanning 1998–2013 and finds that a greater share of loans from nonresident banks, as well as a greater share of foreign banks, reduces both profits and overhead costs in the banking industry of host nations.

As surveyed by Konara et al. (2019), the relationship between financial sector FDI and host country bank efficiency has been documented in the literature at both the country and cross-country levels. These studies vary by countries (or regions) covered, sample period, measurement of efficiency, and methodology, and the findings are not overarching or universally conclusive. Some studies find that foreign banks are more efficient than domestic banks (e.g., Berger et al., 2009; Clarke et al., 2000; Dages et al., 2000), but others show otherwise, that is, foreign banks can be less efficient than domestic banks (e.g., Berger et al., 2000; DeYoung and Nolle, 1996) or about as efficient as incumbent domestic banks (e.g., Vander Vennet, 1996). Regarding the impact of foreign banks, there is evidence that foreign participation is conducive to a more efficient banking system in the host country (e.g., Berger et al., 2009; Bonin et al., 2005; Sturm and Williams, 2004), but others find the opposite or no significant impact. For example, most of the studies find that foreign bank participation has an adverse impact on bank efficiency in advanced economies (e.g., Berger et al., 2000; Chang et al., 1998; DeYoung and Nolle, 1996; Lensink et al., 2008). Konara et al. (2019) try to reconcile the discrepancies in the foreign entry–efficiency relationship by investigating the impact of financial sector FDI on different measures of efficiency (i.e., overall technical, pure technical, scale, cost, and revenue efficiencies) with a sample of eight emerging market economies. Their estimates show that foreign bank competition increases overall technical efficiency and scale efficiency, but has no clear impact on the other efficiency measures.

Since the 2008 financial crisis, especially with the recent trade dispute between the United States and China and the outbreak of the COVID-19 crisis, the debate on globalization has intensified, and the issue of whether bank globalization helps improve bank efficiency has become more prominent for policymaking, multinational banking strategy, as well as academic research. The purpose of this paper is to shed new light on the issue from different perspectives with an updated dataset. Specifically, we add to the literature in several aspects. First, most studies on the link between financial FDI and bank efficiency are country case studies on developing countries, such as those of Barajas et al. (2000) on Colombia, Crystal et al. (2001) on Latin America, Fujii et al. (2014) on India, Mulyaningsih et al. (2015) on Indonesia, and Unite and Sullivan (2001) on the Philippines. Only a few earlier studies cover developed countries, such as those of Chang et al. (1998) and DeYoung and Nolle (1996) on the United States and Sturm and Williams (2004) on Australia. Among the limited number of cross-country studies, most also focus on developing and emerging economies. Some examples include the works of Bonin et al. (2005) on 11 transition economies, Konara et al. (2019) on eight emerging market economies, Williams (2012) on four Latin American countries, and Yıldırım and Philippatos (2007) on 12 transition countries.1 The few studies that cover multiple developed countries include those of Berger et al. (2000) covering France, Germany, Spain, the United Kingdom, and the United States, and Lensink et al. (2008), covering 105 countries.

In this study, we employ a more comprehensive dataset that contains over 17,000 individual banks in 126 countries (81 developed and 45 developing countries) over the period between 1995 and 2013. This broad coverage provides a truly global context for examining the issue. The relatively long time span of the data also encompasses a historical period that witnessed the rapid liberalization of financial markets in many developing countries.

Second, we measure bank globalization with banking sector foreign investment inflows (foreign bank presence in the host country) and outflows (obtaining foreign claims by banks in the home country). Most of the literature views bank globalization as the increasing presence of foreign banks in host countries and estimates the effects of such foreign presence on the host countries’ bank performance, be they foreign or domestic (i.e., the host-country effect). We expand the scope of study by examining the impact of globalization from the perspective of both the host and home countries; that is, when banks establish a presence abroad (investment outflow), we investigate how this outward investment affects their efficiency at home (i.e., the home-country effect).

Third, in addition to investigating the average relationship between bank globalization and efficiency, we also look into how this relationship depends on the regulatory and institutional framework of the host (home) country. Furthermore, we examine the heterogeneous effect of bank globalization on local banks with different ex ante characteristics.

Lastly, we use multiple measures of bank efficiency to provide more robust evidence on the issue. We first measure cost efficiency with a stochastic frontier approach and a translog function. This measure of efficiency gauges the performance of a bank relative to the best performer in the sample. Specifically, cost efficiency compares the cost of a bank with the bank in the sample that incurs the lowest costs with the same outputs and inputs. In addition, we employ a financial ratio measure of cost efficiency that is common in cross-country studies on bank globalization and host country bank efficiency, that is, overhead costs. Consistency across the empirical results from these different measures of efficiency increases the reliability of our analysis.

We find that foreign bank entry has negative impacts on the host country’s cost efficiency, with a more prominent effect for developed countries and countries with a more competitive domestic market. However, the adverse impacts of foreign bank entry can be mitigated by stringent activity restrictions, tight supervision, fewer limitations on foreign banks, a lower market entry barrier, and greater financial freedom. Moreover, we observe that incumbent domestic banks that are large, less risky, and more profitable are affected to a lesser extent by foreign bank presence. Regarding the home country effect, evidence shows that foreign investment outflow in the banking sector helps improve bank efficiency in home countries. Banks located in countries with less supervision power, multiple supervisors, more limitations on foreign banks, less financial freedom, and a more competitive market gain greater efficiency from outward investment. Banks that are more efficient, risky, profitable, and/or smaller ex ante benefit more from their country’s FDI outflow in the banking sector. The evidence presented in this paper is robust to alternative measures of variables and econometric methods.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 discusses the relationship between bank globalization and efficiency. Section 3 details the methodology and data. Section 4 presents and discusses the empirical results. Section 5 concludes the paper.

2. Bank globalization and efficiency

2.1. Banking sector globalization and host country bank efficiency: the host-country effect

Globalization in the banking sector affects host country bank efficiency through different channels. First, foreign presence in the financial sector can increase competition in the host country. Jeon et al. (2011) examine the impact of foreign bank penetration on the competitive structure of host country banking sectors in emerging Asia and Latin America during 1997–2008. They find that an increase in foreign bank penetration enhances competition in the banking sector of those countries. With a sample of 50 countries, Claessens and Laeven (2004) find that countries with greater foreign presence and fewer entry restrictions tend to be more competitive. According to the “quiet life” hypothesis, in a less competitive environment, firms tend to have larger market power and do not have to put effort to maximize their cost efficiency in order to stay profitable. Consequently, the slack management due to the lack of competition results in less efficient firms. Therefore, the “quiet life” hypothesis suggests a competition–efficiency relationship, and supportive evidence has been documented in the literature (e.g., DeYoung et al., 1998; Jayaratne and Strahan, 1998; Koetter et al., 2012). With increased competition from foreign banks, domestic banks have to improve their efficiency to stay viable and competitive.

Second, bank efficiency improvement can arise from the resource transfer effect of FDI. It is well known in the literature that FDI has significant spillover effects on productivity and technology in host markets. Upon reviewing the evolution and consequences of banking sector globalization, especially for emerging markets, Goldberg (2009) concludes that, just as real-side (nonfinancial sector) FDI, financial sector FDI can induce limited technology transfers and productivity gains for the host country. Foreign multinational banks can bring in more sophisticated banking techniques and technology to a country that can help reduce the cost of financial intermediation (Caprio and Honohan, 1999; Levine, 1996). In addition, foreign banks can also bring in more efficient management skills, which are transferred to domestic banks through knowledge spillover within the banking industry. The “quiet life” hypothesis and resource transfer effect both suggest that foreign bank entry improves bank efficiency in the host country.

However, banking globalization can lower the efficiency of domestic banks. First, foreign banks may be able to cherry-pick high-quality customers with low default risk and leave high-risk customers for domestic banks, thus making domestic banks less profitable, inefficient, and less competitive. Detragiache et al. (2008) point out that foreign banks could have an advantage in monitoring high-end customers over domestic banks in developing countries.

Second, there can be impediments to the materialization of the competition–efficiency effect. Such impediments can include the dominance of foreign banks over domestic banks in information technology and client selection. Additionally, as discussed by Stiglitz (1993), facing pressure from more reputable multinational banks, domestic banks have to incur substantially more costs to compete and to stay afloat. This is consistent with the “banking specificities” hypothesis, which states that bank competition has a detrimental impact on cost efficiency (Fungáčová et al., 2013). To minimize the information asymmetries in the banking industry, banks need to monitor their customers, and there exist economies of scale in this process. For instance, maintaining a long-term business relationship can reduce monitoring costs. However, stiff competition makes it more difficult for banks to keep their customers for a long time, and operation costs increase as banks are unable to realize economies of scale in the face of intense competition. Pruteanu-Podpiera et al. (2008) examine the relationship between bank competition and bank efficiency in the Czech Republic over the transition period between 1994 and 2005 and find a negative relationship between competition and efficiency in banking. Furthermore, it can take years for the efficiency improvement to be realized, so it is not surprising to see no efficiency gains with foreign bank entry.

Third, the aforementioned discussions assume foreign bank entry increases host country bank competition. However, this might not always be the case, especially when foreign banks enter the market by merging with or acquiring local banks. Moguillansky et al. (2004) argue that foreign bank entry might not stimulate competition, due to the rent seeking strategies of foreign banks entering the Mexican market through mergers and acquisitions. Yeyati and Micco (2007) examine the impact of foreign penetration in Latin American countries in the 1990s and find that foreign penetration has led to a less competitive banking industry in those countries. Therefore, foreign bank entry is likely to be associated with lower efficiency in the host country.

The conflicting arguments above cannot lead to a clear expectation of the impact of foreign bank presence on host countries’ bank efficiency. Whether foreign bank entry increases or decreases bank efficiency becomes an empirical question.

2.2. Differences in host-country effects of bank globalization between advanced and developing economies

The evolution of bank globalization has not been directionally symmetric between advanced and developing economies. It is more often the case that banks from advanced economies establish a presence in developing economies than otherwise. It is perceivable that the bank efficiency effect of globalization is not symmetric either between advanced and developing economies. Banks in advanced economies are perceived to be more efficient than their counterparts in developing economies due to differences in technology, management proficiency, and the institutional environment. Focarelli and Pozzolo (2005) argue that banks that operate in developed markets are likely to be more efficient and thus hold a comparative advantage with respect to their counterparts in the developing countries. Therefore, the presence of foreign banks, particularly multinational banks from advanced economies, is expected to have a greater impact on the banking industry in general and on bank efficiency in particular in developing economies than the other way round. Jeon et al. (2011) observe that foreign bank penetration only increases banking competition in the host countries when the foreign banks are more efficient and less risky than domestic banks, but not otherwise.2 Therefore, if we assume that the foreign banks in developing countries are, on average, more efficient than incumbent domestic banks, both the resource transfer argument and the competition effect (“quiet life” hypothesis) support the conjecture that the efficiency gain from foreign bank entry should be more prominent in developing countries relative to developed countries.

Foreign bank entry, which often follows the regulatory liberalization of host countries, inevitably changes the ownership structure of banks in host countries, be it in the form of mergers and acquisitions or wholly owned greenfield investments. Thus, banking globalization has led to diversified ownership or increased foreign ownership in the banking industry in host countries. Unsurprisingly, the increase of foreign ownership in banking is more prominent in developing economies than in advanced economies. Goldberg (2009) notes that, following the dissolution of the Soviet Union, foreign bank entry into Central and Eastern Europe in the early 1990s led to the rapid growth of foreign ownership in local banking systems.

Changes in the ownership structure have implications for bank efficiency. An increase in foreign ownership can help improve overall bank efficiency in developing countries through multiple effects. The evidence in the literature shows that foreign banks in developing countries tend to be more efficient than domestic banks (Berger et al., 2004; Bonin et al., 2005). That alone contributes to the overall efficiency in the banking sector in developing countries, assuming no adverse effects of foreign bank entry (e.g., foreign bank dominance resulting in monopolistic behavior). In addition, foreign ownership participation in domestic banks can help improve these banks’ efficiency. In a study of foreign bank ownership and bank efficiency in China, Berger et al. (2009) find that foreign banks are most efficient and the minority foreign ownership of state-owned banks is associated with higher efficiency than those with no foreign ownership.3 Moreover, as discussed before, domestic banks can gain efficiency benefits through the spillover effect from foreign banks, even if they have no foreign ownership. In light of the foregoing discussions, we conjecture that a foreign presence in developing countries has a more pronounced effect on host countries’ bank efficiency than in developed countries.

2.3. Banking sector globalization and home country bank efficiency: the home-country effect

Most studies on globalization and bank efficiency focus on the premise of the host country, that is, what impacts an incoming foreign bank presence has on the host country. Does international presence have a reverse impact on the efficiency of the banking sector at home? This is an important issue to study, since it relates to the motives of banks investing abroad, particularly banks in developing countries investing in advanced economies. However, we are not aware of research that specifically examines this topic and endeavor to explore the topic as part of our effort in this paper.

Like foreign investment in other industries, banks expand their business to foreign countries to follow their clients, diversify their portfolio, or seek higher profits and/or profit growth (García-Herrero and Navia, 2003). The international presence of banks can contribute to efficiency improvement at home, as well as abroad. On the one hand, banks can learn and develop more advanced technology and management skills in their foreign operations and apply them to their operations at home, thus improving their home bank efficiency. The improvement in efficiency through an international presence can be termed the international learning effect.

Additionally, through international diversification and portfolio optimization, banks that have an international presence can better allocate their resources and improve efficiency at home. We denote this benefit from globalization the resource allocation effect. In a study of banking globalization and monetary transmission, Cetorelli and Goldberg (2012) conjecture that global banks can respond to a domestic liquidity shock by activating a cross-border internal capital market between the head office and its foreign offices, thus reallocating funds based on relative needs. This international connectedness between the head office and foreign subsidiaries allows banks to better manage their risks and balance their assets and liabilities and thus improve their efficiency. We summarize the international learning and resource allocation effects in the following hypothesis: the international expansion of banks improves their efficiency at home.

As discussed earlier, banks in developing countries benefit more from incoming foreign banks from spillover in technology and management skills than banks in advanced economies do. Similarly, the international learning effect should also be more prominent for banks in developing countries, since banks in developed countries are generally more efficient (Focarelli and Pozzolo, 2005), and foreign banks in developed countries are mostly less efficient than the local banks (Berger et al., 2004).

3. Methodology and data

We adopt a two-step approach to study the impact of globalization on bank efficiency. In the first step, we estimate bank efficiency with a stochastic frontier approach and select an alternative bank efficiency measure. In the second step, we estimate an equation linking banking sector globalization to bank efficiency measures. In the following, we first discuss the measurement of the variables and their data sources and then describe the estimation models.

3.1. Measurement of bank efficiency and bank globalization

We measure bank efficiency in two ways. First, we adopt a stochastic frontier approach that has been recently applied to country-specific studies of bank efficiency. In addition, we measure bank efficiency with a financial ratio that is commonly used in the literature. This dichotomy allows us to cross-check the robustness of our analysis.

3.1.1. Bank efficiency measured with the stochastic frontier approach

As reviewed by Konara et al. (2019), besides the financial ratio measures, the two most widely used methods to estimate bank efficiency are parametric stochastic frontier analysis (SFA) and nonparametric data envelopment analysis. Studies using SFA include those of Berger et al. (2004, 2009), Bonin et al. (2005),Hasan and Marton (2003), and Williams (2012), and studies using data envelopment analysis include those of Konara et al. (2019), Sturm and Williams (2004), Tan and Anchor (2017), and Tan and Floros (2018). Most of the studies that focus on profit or cost efficiencies use SFA. Since this research tries to examine how bank globalization affects bank cost efficiency in host and home countries, we follow the literature and use SFA to estimate bank cost efficiency. As Kumbhakar and Lovell (2000) point out, the approach introduces one-sided error components designed to capture the effects of inefficiency. This method is relatively new compared with the older least squares–based approach to the estimation of production, cost, revenue, and profit functions. The application of SFA to bank efficiency allows us to gauge the performance of a bank relative to the best-practice bank in terms of costs, that is, the cost frontier.

We employ a translog functional form with three inputs and four outputs to estimate the cost frontier function. The three input price (w) variables are the price of labor (, the price of physical capital (, and the price of borrowed funds (). The four output (y) variables include (1) total loans, (2) total deposits, (3) liquid assets, and (4) other earning assets. The empirical model that we use to estimate cost efficiency is specified as

| (1) |

Where, for bank i and year t, , , and C represents total costs. Normalization by one of the input prices ( ensures price homogeneity.4 We also include country and year dummies to estimate the frontier. The country dummy is used to capture otherwise unobserved differences among banks that could be attributable to the legal, institutional, or macroeconomic conditions of their country of origin and the markets in which they operate. As indicated by Lozano-Vivas et al. (2002), failure to account for such systematic differences across countries leads to contaminated inefficiency scores. The year dummy allows for a time trend to influence the efficiency of banks, reflecting the impact of technology shifts and other time-dependent effects.

A bank’s cost efficiency is estimated with the efficiency factor , assuming an exponential distribution for the inefficiency term. According to the frontier approach, the minimum cost is set at one for the best-practice bank in the sample, and any other bank’s cost efficiency measure is higher than one, with the difference being an indicator of inefficiency compared with the frontier bank. For example, a cost efficiency score of 1.2 for a particular bank means that its costs are 20 % higher than those of the most efficient bank. Therefore, a higher score indicates lower efficiency. To reduce confusion, we call this estimated score the cost inefficiency.

3.1.2. Financial ratio measure of bank efficiency

In addition to the relative efficiency measure estimated with the stochastic frontier model, we also employ an alternative financial ratio measure of bank efficiency that is common in the literature. Specifically, we use overhead costs to proxy for bank cost efficiency. The variable overhead costs is the ratio of non-interest expenses to total assets, with a higher ratio indicating lower cost efficiency.

3.1.3. Measures of bank globalization

We follow the literature in adopting multiple measures for a country’s banking sector globalization, including foreign bank assets, foreign bank numbers, and foreign claims. The variable foreign bank assets is the percentage of total banking assets held by foreign banks. A bank with 50 % or more of its shares owned by foreign investors is considered a foreign bank (or a foreign-owned bank). The variable foreign bank numbers is the number of foreign-owned banks as a percentage of the total number of banks in an economy. Both variables measure the presence of foreign banks in the host country. The data for both variables were originally collected by Claessens and Van Horen (2014) and cover 1995–2013 for foreign bank numbers and 2004–2013 for foreign bank assets.

The variable foreign claims is constructed as the ratio of consolidated foreign claims by domestic banks to the home country’s gross domestic product (GDP). To illustrate, US banks’ investments abroad are US banks’ foreign claims and are measured as the ratio of these claims to the US GDP. More specifically, foreign claims include the home banks’ cross-border claims plus their foreign subsidiary local claims in all currencies. Foreign claims gauge the extent to which a country’s banking sector expands its business outside the home country. Data for foreign claims are obtained from the Bank for International Settlements.

3.1.4. Control variables

In our empirical analysis, we control for bank characteristics and country-level variables that gauge a country’s macroeconomic situation, financial environment, legal environment, and economic cycle. Bank-level variables are used to control for bank characteristics that are found to have a significant impact on bank efficiency in the literature. These variables include bank size, capital adequacy, loan share, asset growth, and Z score. Bank size matters in scale economy and, in turn, in efficiency; capital adequacy entails the safety of a bank and its funding costs; the loan share indicates a bank’s business orientation; asset growth shows the bank’s development; and the Z score measures insolvency risk. These variables have been found to be related to bank efficiency in the literature (e.g., Konara et al., 2019; Lensink et al., 2008). We use the logarithm of total assets to measure bank size, the capital-to-assets ratio for capital adequacy, the ratio of loans to total assets for the loan share, and the percentage change in total assets for asset growth. For bank i in year t, the Z score is constructed as , where represents the return on assets for, is the capital-to-assets ratio, and is the standard deviation of the return on assets, calculated only for the banks with at least four consecutive years of data. The data for the bank-level variables are retrieved from the BankScope database.

The macroeconomic environment affects bank performance and efficiency. Our macroeconomic variables include GDP per capita and GDP growth rate. The GDP per capita indicates the development level of an economy, while GDP growth reflects the dynamics of the economy. Data for these variables are obtained from the World Development Indicators database of the World Bank.

We describe a country’s financial environment with five variables, as follows: financial freedom measures the independence of the financial and banking sector from government control and interference. It incorporates the extent of the government regulation of financial services, government ownership, financial development, the government’s influence on credit allocation and openness to competition. The variable values range from zero to 100, with higher values representing greater freedom. The Heritage Foundation compiles data on financial freedom. The variable Boone indicator is a measure of the degree of competition. It is defined as the elasticity of profit to marginal costs, with smaller values indicating greater competition (Boone et al., 2005; Schaeck and Cihák, 2014). Bank concentration is measured with the Herfindahl–Hirschman Index, HHI.5 It is the sum of the squares of bank market shares in a country, with a higher value indicating greater concentration. A highly concentrated banking system dominated by a few large banks tends to be less efficient, according to the structure–conduct–performance hypothesis. The variable HHI is calculated by the authors with data from BankScope. The variable deposit money bank assets is defined as claims on the domestic real nonfinancial sector by deposit money banks as a share of the GDP, and it is used to measure the importance of the role that the banking system plays in a country. A higher ratio implies greater importance of the banking system in providing financing to the economy. The variable stock market capitalization, defined as the value of listed equity as a share of the GDP, measures a country’s stock market development and general level of financial development (Rajan and Zingales, 2003). Data for most of the financial environment variables have been compiled by Beck et al. (2000), Beck and Demirgüç-Kunt (2009), and Cihák et al. (2012) and are obtained from the World Bank’s Global Financial Development Database, except for financial freedom, the Boone indicator, and the HHI.

Our analysis also controls for a country’s legal environment. We employ a governance indicator compiled by the World Bank and retrieved from the World Governance Indicators database, rule of law. By definition, the rule of law captures perceptions of the extent to which agents have confidence in and abide by the rules of society. By construction, the rule of law ranges from approximately -2.5 to 2.5, with higher values representing stronger governance performance. Finally, we include a crisis dummy variable, crisis, in the regressions to take into account the impact of business cycles on bank efficiency. The variable equals one if a country is experiencing a systemic crisis, and zero otherwise.

3.2. Estimation of the effects of globalization on bank efficiency

In the second step, we use an unbalanced panel dataset to examine the relationship between bank globalization and efficiency. We estimate a panel model with ordinary least squares with bank and time fixed effects and clustering at the bank level. The set of baseline regressions we estimate are summarized as follows:

| (2) |

Where, for bank i, country j, and year t, is the bank efficiency measure; represents the level of the bank globalization of a country; and are matrices of bank- and country- level control variables, respectively; is the error term; and , , and are the parameters to be estimated. The parameter of interest is , the coefficient of bank globalization. Considering that the control variables are correlated with the main independent variable, that is, the measure of bank globalization, we orthogonalize the bank globalization measure with respect to the country-level control variables to isolate the effect of bank globalization on cost efficiency. Specifically, we regress the bank globalization measure on the country-level control variables and use the residuals to proxy for globalization.6

Berger et al. (2009) argue that time fixed effects should be avoided in the second-step regressions, given that the efficiency scores have been adjusted for the sample years in the first step. Therefore, to avoid adjusting time twice, we do not include year dummies when cost inefficiency from SFA is the dependent variable. Nonetheless, the results are qualitatively similar when we try to include these time fixed effects in the regressions. In addition, considering that the impact of bank globalization can take some time to materialize, and to minimize the potential endogeneity issue, we use one-year-lagged country-level variables in the regressions.7

The results from model (2) can only describe the average relationship between bank globalization and cost efficiency. This relationship can depend on the host and home countries’ regulatory and institutional regimes, and bank globalization could have a heterogeneous impact on domestic banks with different ex ante characteristics as well. To further investigate this potential heterogeneity, we modify the baseline model (2) by adding the interaction terms between bank globalization measures and the bank regulatory/institutional variables or bank characteristics variables, as follows:

| (3) |

| (4) |

Where R is a vector of bank regulatory and institutional variables and B represents ex ante bank characteristics. Specifically, R includes the variables activity restrictions, supervision power, multiple supervisors, limitations on foreign banks, applications denied, Boone indicator, and financial freedom. The variable activity restrictions gauges the extent to which a bank can be engaged in fee-generating activities. Its values range from 3 to 12, with higher values indicating more restrictions on bank activities. The variable supervision power measures the extent to which the supervisory authorities have the authority to take specific actions to prevent and correct problems. It ranges from 0 to 14, with higher values representing greater power. The variable multiple supervisors is a dummy variable that takes on the value of one if there is more than one supervisory body, and zero otherwise. A system with multiple supervisory bodies tends to provide better supervision, since banks are supervised from different perspectives. Both supervision power and multiple supervisors gauge the effectiveness of bank supervision. The variable limitations on foreign banks measures the activities that foreign banks are allowed in the host country, with a higher number indicating fewer restrictions on foreign banks. The variable applications denied is the percentage of applications to enter banking that have been denied. Both limitations on foreign banks and applications denied gauge a country’s market entry barrier. These regulatory and institutional variables are obtained from four surveys conducted by the World Bank in 2001, 2003, 2007, and 2001, respectively. The data used in this study are the average values of these variables from the four surveys. In addition, we include Boone indicator and financial freedom to measure a country’s institutional environment.

Ex ante bank characteristics B includes bank efficiency (cost efficiency, overhead costs), insolvency risk (Z score), profitability (return on assets), and size (bank assets), as defined earlier. We generate a dummy variable for each of these characteristics that equals one if the value is higher than the sample mean, and zero otherwise. One-year lags of these dummy variables are used.

3.3. Dataset

Our bank sample includes commercial banks, bank holding companies, savings banks, and cooperative banks. All the bank-level data are retrieved from the BankScope database provided by Bureau Van Dijk. We start with the whole dataset and make a few adjustments according to the following criteria. First, we exclude from the dataset countries with data for fewer than five banks for any given year. Second, we delete observations with obvious data errors (e.g., negative or zero total assets, negative or zero loans). Third, if both consolidated and unsolicited bank data are reported in the dataset, we keep only the consolidated data to avoid double counting. Since the bank globalization and bank ownership data are only available from 1995 to 2013, we end up with a dataset covering more than 17,000 banks in 126 countries from 1995 to 2013. The data for the country-level variables are compiled from various datasets, and the detailed variable definitions and data sources are summarized in Table 1 .

Table 1.

Variable definitions and data sources.

| Variables | Definition | Data Source |

|---|---|---|

| Dependent variables: | ||

| Cost inefficiency | Estimated with a stochastic frontier approach (model (1)) and is greater than 1, with a higher score associated with lower efficiency | BankScope |

| Overhead costs | Non-interest expense as a percentage of total assets | BankScope |

| Bank globalization measures: | ||

| Foreign bank assets | Percentage of total banking assets held by foreign banks | Global Financial Development Database |

| Number of foreign banks | Number of foreign-owned banks as a percentage of the total number of banks in an economy | Global Financial Development Database |

| Foreign claims | Ratio of consolidated foreign claims to the GDP | Global Financial Development Database |

| Bank characteristics: | ||

| Bank assets | Logarithm of bank assets (in millions of US dollars) to proxy for bank size | BankScope |

| Capital asset ratio | Ratio of equity capital to bank assets to measure capital adequacy | BankScope |

| Loan share | Ratio of loans to total assets to proxy for a bank’s business orientation | BankScope |

| Asset growth | Percentage growth in bank total assets | BankScope |

| Z score | , where, for bank i in year t, represents the return on assets, is the capital-to-assets ratio, and is the standard deviation of the return on assets, which is calculated only for banks with at least four consecutive years of data | BankScope |

| Macroeconomic variables: | ||

| GDP per capita | GDP per capita, in thousands of 2005 constant US dollars | World Development Indicators |

| GDP growth | Growth rate of the GDP, as a percentage | |

| Financial environment variables: | ||

| Financial freedom | Measure of independence from government control and interference | Heritage Foundation |

| Boone indicator | Elasticity of profits to marginal costs, a measure of the degree of competition | Global Financial Development Database |

| HHI | Herfindahl–Hirschman Index, i.e., the sum of the squares of bank market shares in a country | BankScope |

| Deposit money bank assets | Claims on the domestic real nonfinancial sector by deposit money banks as a share of the GDP | Global Financial Development Database |

| Stock market capitalization | Value of listed shares as a share of the GDP | |

| Legal Variable: | ||

| Rule of law | Perceptions of the extent to which agents have confidence in and abide by the rules of society | Worldwide Governance Indicators Database |

| Economic cycle variable: | ||

| Crisis | Dummy that equals 1 if a country is undergoing a systemic crisis, and 0 otherwise | Global Financial Development Database |

| Regulatory and institutional variables: | ||

| Activity restrictions | Range of fee-generating activities banks can participate in, with higher values indicating more restrictive regulations | Bank Regulation and Supervision Database, Barth et al. (2008, 2013), Cihák et al. (2012) |

| Supervision power | Whether the supervisory authorities have the authority to take specific actions to prevent and correct problems | |

| Multiple supervisors | Dummy equal to 1 when there are multiple supervisors | |

| Limitations on foreign banks | Whether foreign banks can own domestic banks and whether foreign banks can enter a country's banking industry, with values ranging from 0 to 4, with lower values indicating greater stringency | |

| Applications denied | Fraction of applications to enter banking that are denied | |

3.4. Summary statistics

Table 2 displays the summary statistics of all the variables used in this study. Cost efficiency ranges from 1.054 to 4.397, with a mean of 1.284, implying the average bank incurs 28.4 % more costs than a fully efficient bank. Overhead costs fall within the range of [0.53 33.98], with an average of 3.938, suggesting that, on average, a bank’s non-interest costs account for 3.938 % of its total assets.

Table 2.

Summary statistics of bank efficiency, globalization, and control variables.

| Variables | No. of observations | Mean | Standard deviation | Minimum | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bank efficiency measures: | |||||

| Cost inefficiency | 204,240 | 1.284 | 0.331 | 1.054 | 4.397 |

| Overhead costs | 220,725 | 3.938 | 3.334 | 0.530 | 33.980 |

| Bank globalization measures: | |||||

| Foreign bank numbers | 222,401 | 23.119 | 13.910 | 1 | 83 |

| Foreign bank assets | 134,754 | 18.594 | 15.286 | 1 | 92 |

| Foreign claim | 216,531 | 38.841 | 27.004 | 0.194 | 175.857 |

| Bank characteristics: | |||||

| Bank assets | 225,852 | 6.081 | 1.728 | 2.197 | 11.528 |

| Capital asset ratio | 225,294 | 10.609 | 8.337 | 2.130 | 78.750 |

| Loan share | 224,837 | 60.636 | 17.524 | 0.004 | 91.941 |

| Asset growth | 202,834 | 10.127 | 18.161 | −25.760 | 135 |

| Z score | 187,888 | 35.171 | 33.598 | 1.621 | 237.522 |

| Macroeconomic variables: | |||||

| GDP per capita | 225,007 | 35.528 | 14.089 | 0.514 | 60.534 |

| GDP growth | 225,314 | 2.265 | 2.464 | −5.619 | 9.269 |

| Financial environment variables: | |||||

| Financial freedom | 223,681 | 69.755 | 17.190 | 10 | 90 |

| Boone indicator | 206,876 | −0.054 | 0.102 | −3.196 | 1.907 |

| HHI | 225,491 | 0.098 | 0.138 | 0.013 | 1.000 |

| Deposit money bank assets | 220,561 | 82.047 | 44.213 | 14.931 | 221.547 |

| Stock market capitalization | 205,891 | 94.875 | 45.928 | 6.039 | 216.159 |

| Legal environment variable: | |||||

| Rule of law | 221,397 | 1.230 | 0.766 | −1.123 | 1.943 |

| Economic cycle variable: | |||||

| Crisis | 197,312 | 0.297 | 0.457 | 0 | 1 |

| Regulatory and institutional variables: | |||||

| Activity restrictions | 224,536 | 7.419 | 1.720 | 3.333 | 12 |

| Supervision power | 223,158 | 11.950 | 1.963 | 6 | 14.500 |

| Multiple supervisors | 224,485 | 0.652 | 0.443 | 0 | 1 |

| Limitations on foreign banks | 223,746 | 3.931 | 0.269 | 0 | 4 |

| Applications denied | 209,290 | 0.033 | 0.094 | 0 | 0.893 |

Notes: This table displays the summary statistics of the bank efficiency and globalization measures, as well as the control variables. Although most variables are ratios or indexes, the GDP per capita is in thousands of US dollars. Variable definitions and data sources are reported in Table 1.

As measures of bank globalization, foreign bank numbers and foreign bank assets proxy for the level of foreign bank presence in the host countries. The average number of foreign banks accounts for 23.119 % of the total number of banks in the host countries. On average, foreign bank assets account for 18.594 % of total bank assets. These two measures seem to suggest that foreign banks, which exist in the host countries as subsidiaries or branches of parent banks, are generally smaller than the incumbent domestic banks in terms of assets. Foreign claims represent a country’s expansion to other countries in the banking sector. The average consolidated foreign claims are 38.841 % of the GDP.

Turning to the bank characteristics variables, bank assets, measured as the logarithm of bank assets in millions of US dollars, ranges from 2.197 to 11.528, with a mean of 6.081. The capital asset ratio, calculated as the ratio of bank equity capital to total assets, has a mean of 10.609 %. The average loan share, the ratio of loans to assets, is 60.636 %, indicating the average bank’s loans account for 60.636 % of total assets. On average, bank assets grow at a rate of 10.127 % and the bank Z score is 35.171.

Our macroeconomic variables are the GDP per capita and GDP growth. Over the sample period of 1995–2013, the average GDP per capita of all the countries in the sample is 35,528 US dollars, and the average GDP growth rate is 2.265 %. For the financial environment variables, financial freedom ranges from 10 to 90, with an average of 69.755, indicating that the financial systems of the countries covered in this study range from “near repressive” to “minimal government interference” and, on average, fall into the category “limited government interference,” according to the Heritage Foundation’s categorization.8 The average of the competition measure Boone indicator is -0.054, and the average measure of concentration, HHI, is 0.098. The ratio of deposit money bank assets to the GDP estimates the importance of the banking sector in an economy, and the average is 82.047 %. Stock market capitalization, that is, the value of listed shares as a percentage of the GDP, measures the importance of an alternative source of funds to banks, and is, on average, 94.875 %, ranging from 6.039 % to 216.159 %. Regarding the legal environment and economic cycle variables, the average of rule of law is 1.23, and the average of the crisis dummy is 0.297. The averages of the regulatory and institutional variables are 7.419 for activity restrictions, 11.95 for supervision power, 0.652 for multiple supervisors, 3.931 for limitations on foreign banks, and 0.033 for applications denied.

Table 3 lists the correlation matrix of all the variables of this study. These variables are all significantly correlated with each other at the 1 % level. Without controlling for the other variables, the pairwise correlation between the cost efficiency measures (cost inefficiency and overhead costs) are positivity correlated with the number of foreign banks, indicating that a foreign bank presence in host countries increases cost inefficiency. However, cost inefficiency is negatively associated with foreign bank assets, where overhead costs are positively associated, rendering conflicting evidence. Both cost inefficiency and overhead costs are negatively correlated with foreign claims, providing preliminary evidence that foreign expansion reduces cost inefficiency in home countries.

Table 3.

Correlation matrix of the variables.

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2 | 0.52 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3 | 0.06 | 0.14 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 4 | −0.01 | 0.09 | 0.72 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 5 | −0.02 | −0.16 | 0.20 | 0.11 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 6 | 0.02 | −0.21 | −0.03 | 0.01 | 0.14 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 7 | 0.26 | 0.37 | 0.16 | 0.08 | −0.03 | −0.26 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||

| 8 | −0.17 | −0.10 | −0.11 | −0.11 | 0.06 | −0.06 | −0.19 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||

| 9 | 0.02 | 0.18 | 0.08 | 0.11 | −0.10 | −0.02 | 0.09 | −0.04 | 1 | |||||||||||||||

| 10 | −0.12 | −0.20 | −0.16 | −0.17 | 0.17 | 0.01 | −0.02 | 0.04 | −0.15 | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| 11 | −0.17 | −0.38 | −0.16 | −0.25 | 0.25 | −0.06 | −0.23 | 0.26 | −0.25 | 0.16 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| 12 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.10 | 0.13 | −0.19 | −0.05 | 0.10 | −0.09 | 0.20 | −0.08 | −0.29 | 1 | ||||||||||||

| 13 | −0.15 | −0.21 | 0.18 | 0.12 | 0.22 | −0.16 | −0.07 | 0.22 | −0.08 | 0.00 | 0.66 | −0.16 | 1 | |||||||||||

| 14 | 0.00 | −0.06 | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.07 | −0.05 | −0.07 | −0.07 | 0.02 | 0.10 | −0.06 | −0.02 | 1 | ||||||||||

| 15 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.31 | 0.23 | 0.25 | 0.12 | 0.14 | −0.14 | 0.10 | −0.02 | −0.33 | 0.16 | −0.25 | 0.04 | 1 | |||||||||

| 16 | −0.02 | −0.27 | −0.35 | −0.24 | 0.43 | 0.35 | −0.22 | −0.03 | −0.18 | 0.25 | 0.14 | −0.31 | −0.23 | 0.12 | 0.10 | 1 | ||||||||

| 17 | −0.09 | −0.16 | 0.13 | −0.06 | 0.05 | −0.18 | −0.01 | 0.20 | −0.02 | 0.00 | 0.63 | 0.14 | 0.62 | −0.05 | −0.16 | −0.27 | 1 | |||||||

| 18 | −0.21 | −0.45 | −0.19 | −0.18 | 0.29 | 0.02 | −0.30 | 0.23 | −0.28 | 0.21 | 0.91 | −0.29 | 0.59 | 0.09 | −0.35 | 0.28 | 0.47 | 1 | ||||||

| 19 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.16 | −0.20 | 0.14 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.06 | −0.10 | −0.01 | 0.16 | −0.43 | −0.03 | 0.05 | −0.07 | 0.07 | −0.07 | 0.08 | 1 | |||||

| 20 | −0.05 | −0.03 | 0.16 | 0.06 | −0.42 | −0.12 | 0.05 | 0.11 | 0.05 | −0.30 | 0.10 | 0.12 | 0.31 | −0.05 | −0.23 | −0.58 | 0.41 | −0.04 | 0.04 | 1 | ||||

| 21 | −0.05 | −0.09 | 0.30 | 0.13 | −0.14 | −0.18 | −0.02 | 0.14 | −0.02 | −0.15 | 0.42 | 0.05 | 0.57 | −0.05 | −0.22 | −0.47 | 0.65 | 0.31 | 0.05 | 0.68 | 1 | |||

| 22 | −0.20 | −0.18 | 0.02 | −0.10 | −0.18 | −0.25 | −0.15 | 0.23 | −0.12 | 0.05 | 0.60 | −0.09 | 0.58 | −0.08 | −0.55 | −0.41 | 0.49 | 0.59 | 0.08 | 0.37 | 0.58 | 1 | ||

| 23 | −0.22 | −0.40 | −0.07 | −0.05 | 0.22 | 0.09 | −0.26 | 0.12 | −0.20 | 0.11 | 0.56 | −0.20 | 0.40 | 0.09 | −0.22 | 0.22 | 0.24 | 0.63 | −0.02 | 0.09 | 0.23 | 0.34 | 1 | |

| 24 | 0.05 | 0.14 | 0.08 | 0.15 | −0.03 | 0.08 | 0.14 | −0.12 | 0.12 | −0.10 | −0.54 | 0.16 | −0.29 | −0.03 | 0.31 | −0.08 | −0.27 | −0.58 | −0.07 | 0.03 | −0.19 | −0.42 | −0.10 | 1 |

Notes: This table reports the correlation matrix of all the variables in this study. The correlations are all significant at 1 % level. The variables are 1) cost inefficiency, 2) overhead costs, 3) foreign bank numbers, 4) foreign bank assets, 5) foreign claims, 6) bank assets, 7) capital asset ratio, 8) loan share, 9) asset growth, 10) Z score, 11) GDP per capita, 12) GDP growth, 13) financial freedom, 14) Boone indicator, 15) HHI, 16) deposit money bank assets, 17) stock market capitalization, 18) rule of law, 19) crisis, 20) activity restrictions, 21) supervision power, 22) multiple supervisors, 23) limitations on foreign banks, and 24) applications denied.

4. Empirical results

4.1. Impact of foreign bank entry on host country bank efficiency: the host-country effect

We run separate regressions with separate efficiency and globalization measures and subsamples, as specified in model (2), using unbalanced panel data. Table 4 displays the regression results of the impact of foreign bank entry on the host country’s cost efficiency. Columns (1) to (4) show strong and consistent evidence that foreign bank numbers are positively associated with both cost inefficiency and overhead costs, suggesting that foreign bank presence increases cost inefficiency. With foreign bank assets as a proxy for foreign bank presence, columns (5) to (8) display the same evidence. The findings here are at variance with some studies (e.g., Berger et al., 2009; Unite and Sullivan, 2001), but are consistent with others (e.g., Chang et al., 1998; Lensink et al., 2008).

Table 4.

Foreign bank entry and host country bank efficiency (host-country effect).

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cost inefficiency | Cost inefficiency | Overhead costs | Overhead costs | Cost inefficiency | Cost inefficiency | Overhead costs | Overhead costs | |

| All banks | Domestic banks | All banks | Domestic banks | All banks | Domestic banks | All banks | Domestic banks | |

| Foreign bank numbers | 0.0091*** | 0.0111*** | 0.0209*** | 0.0247*** | ||||

| (0.0006) | (0.0006) | (0.0037) | (0.0041) | |||||

| Foreign bank assets | 0.0014*** | 0.0035*** | 0.0354*** | 0.0573*** | ||||

| (0.0004) | (0.0005) | (0.0032) | (0.0040) | |||||

| Bank assets | −0.0449*** | −0.0356*** | −0.5152*** | −0.4668*** | −0.0233** | −0.0215** | −0.3049*** | −0.3353*** |

| (0.0061) | (0.0061) | (0.0460) | (0.0473) | (0.0102) | (0.0106) | (0.0807) | (0.0865) | |

| Capital asset ratio | 0.0144*** | 0.0142*** | 0.0794*** | 0.0792*** | 0.0165*** | 0.0171*** | 0.0917*** | 0.0986*** |

| (0.0011) | (0.0012) | (0.0075) | (0.0086) | (0.0015) | (0.0016) | (0.0111) | (0.0128) | |

| Loan share | −0.0009*** | −0.0007*** | 0.0084*** | 0.0092*** | −0.0016*** | −0.0014*** | 0.0048** | 0.0059** |

| (0.0002) | (0.0002) | (0.0014) | (0.0014) | (0.0003) | (0.0003) | (0.0023) | (0.0024) | |

| Asset growth | −0.0009*** | −0.0010*** | −0.0026*** | −0.0030*** | −0.0013*** | −0.0014*** | −0.0065*** | −0.0071*** |

| (0.0001) | (0.0001) | (0.0006) | (0.0006) | (0.0001) | (0.0001) | (0.0009) | (0.0010) | |

| Z score | −0.0016*** | −0.0014*** | −0.0206*** | −0.0195*** | −0.0017*** | −0.0017*** | −0.0287*** | −0.0302*** |

| (0.0002) | (0.0002) | (0.0015) | (0.0016) | (0.0003) | (0.0003) | (0.0026) | (0.0027) | |

| GDP per capita | 0.0188*** | 0.0251*** | 0.0883*** | 0.1513*** | 0.0179*** | 0.0269*** | 0.2204*** | 0.3508*** |

| (0.0020) | (0.0022) | (0.0136) | (0.0166) | (0.0030) | (0.0035) | (0.0210) | (0.0265) | |

| GDP growth | −0.0188*** | −0.0227*** | −0.1558*** | −0.1856*** | −0.0232*** | −0.0278*** | −0.1760*** | −0.2160*** |

| (0.0011) | (0.0013) | (0.0080) | (0.0095) | (0.0013) | (0.0015) | (0.0108) | (0.0125) | |

| Financial freedom | 0.0012*** | 0.0023*** | 0.0118*** | 0.0142*** | −0.0000 | 0.0012*** | 0.0358*** | 0.0455*** |

| (0.0003) | (0.0003) | (0.0019) | (0.0021) | (0.0003) | (0.0004) | (0.0028) | (0.0033) | |

| Boone indicator | 0.0608** | 0.0500 | −0.3335* | −0.7380*** | −0.1813*** | −0.1118 | 0.1595 | 0.6903 |

| (0.0297) | (0.0492) | (0.1793) | (0.2849) | (0.0679) | (0.0750) | (0.3066) | (0.4493) | |

| HHI | 0.3845*** | 0.5131*** | 0.7669*** | 1.0842*** | 0.0850** | 0.3109*** | 1.2928*** | 2.7702*** |

| (0.0313) | (0.0338) | (0.1778) | (0.2061) | (0.0340) | (0.0456) | (0.1863) | (0.2525) | |

| Deposit money bank assets | −0.0025*** | −0.0030*** | −0.0018** | −0.0022** | −0.0020*** | −0.0027*** | −0.0015 | −0.0057*** |

| (0.0002) | (0.0002) | (0.0008) | (0.0008) | (0.0002) | (0.0002) | (0.0011) | (0.0014) | |

| Stock market capitalization | −0.0006*** | −0.0008*** | −0.0027*** | −0.0031*** | −0.0011*** | −0.0017*** | −0.0279*** | −0.0350*** |

| (0.0001) | (0.0002) | (0.0009) | (0.0010) | (0.0002) | (0.0002) | (0.0015) | (0.0019) | |

| Rule of law | 0.1030*** | 0.1800*** | 2.0985*** | 2.8993*** | 0.3895*** | 0.4938*** | 4.2751*** | 5.5171*** |

| (0.0272) | (0.0310) | (0.2004) | (0.2443) | (0.0330) | (0.0383) | (0.2913) | (0.3529) | |

| Crisis | 0.0890*** | 0.0885*** | 0.4692*** | 0.4355*** | 0.0473*** | 0.0366*** | 0.4961*** | 0.4416*** |

| (0.0051) | (0.0052) | (0.0332) | (0.0326) | (0.0050) | (0.0051) | (0.0412) | (0.0436) | |

| N | 123313 | 118605 | 130861 | 125410 | 76836 | 73398 | 80692 | 76801 |

| R2 | 0.109 | 0.119 | 0.099 | 0.107 | 0.117 | 0.132 | 0.128 | 0.150 |

Notes: This table shows the results of regressions as specified in model (2). All regressions are clustered at the bank level, with bank fixed effects. Year fixed effects are included when overhead costs is the dependent variable. The variable definitions and data sources are reported in Table 1. Standard errors are in parentheses, and *, **, and *** denote significance at the 10 %, 5 %, and 1 % levels, respectively.

Table 4 also provides estimates for the control variables. For the bank characteristics, the results suggest that banks with larger assets tend to be more efficient, reflecting economies of scale. Banks with higher ratios of capital are less cost-efficient in all specifications, indicating maintaining more capital could be costly and cause inefficiency. The negative coefficients for asset growth and the Z score across all regressions imply that banks that grow quickly and those with lower insolvency risk tend to be more efficient. The positive estimates for the GDP per capita suggest that bank cost efficiency is lower in countries with a higher GDP per capita, which is counterintuitive and could be due to multicollinearity between the GDP per capita and other control variables. Table 3 shows that the correlation between the GDP per capita and financial freedom, stock market capitalization, and the rule of law are 0.66, 0.63, and 0.91, respectively. Further robustness checks, discussed later, show that the relationship between the GDP per capita and bank efficiency is sensitive to the measures of cost efficiency. Therefore, no clear relationship is obtained. The coefficients for GDP growth are consistently significant and negative across all regressions, indicating that bank efficiency is higher during periods of rapid economic growth. The market concentration (HHI) is linked to greater inefficiency, which is consistent with the structure–conduct–performance hypothesis. Banks are more efficient if the banking sector plays a more important role in the country’s financial system, as indicated by the negative coefficients for deposit money bank assets. Banks have higher efficiency in countries with a more developed stock market. The rule of law is positively related to cost inefficiency, implying that following the rule of law could incur more costs and lead to inefficiency. Not surprisingly, we find that bank efficiency is lower during periods of systemic crisis. Banks’ business orientation (loan share) and the host countries’ financial freedom and competition (Boone indicator) show no consistent relationship with bank efficiency, with conflicting evidence from different specifications.

4.2. Impact of foreign expansion on home country bank efficiency: the home-country effect

We further examine whether the extent of outward foreign investment in the banking sector has an impact on home country bank efficiency (home-country effect). Table 5 reports the relationship between foreign claims, a measure of a country foreign investment outflow, and bank efficiency. With alternative measures of bank efficiency and samples, the negative and significant coefficients for foreign claims across all regressions indicate that international expansion in the banking sector helps improve home country bank efficiency. As argued earlier, the international learning and resource allocation effects of international expansion could contribute to the improvement of bank efficiency in home countries. The estimates for the control variables are mostly the same as presented in Table 4, except that financial freedom and the Boone indicator here show consistently negative coefficients, suggesting that banks tend to be more efficient in countries with less government interference and a more competitive banking market. Table 5 presents no consistent evidence regarding the relationship between bank concentration and efficiency.

Table 5.

Foreign expansion and home country bank efficiency (home-country effect).

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cost inefficiency | Cost inefficiency | Overhead costs | Overhead costs | |

| All banks | Domestic banks | All banks | Domestic banks | |

| Foreign claims | −0.0004*** | −0.0006*** | −0.0067*** | −0.0083*** |

| (0.0001) | (0.0001) | (0.0011) | (0.0012) | |

| Bank assets | −0.0520*** | −0.0513*** | −0.5183*** | −0.4885*** |

| (0.0052) | (0.0054) | (0.0452) | (0.0462) | |

| Capital asset ratio | 0.0147*** | 0.0149*** | 0.0800*** | 0.0804*** |

| (0.0011) | (0.0012) | (0.0075) | (0.0085) | |

| Loan share | −0.0008*** | −0.0007*** | 0.0091*** | 0.0097*** |

| (0.0002) | (0.0002) | (0.0014) | (0.0014) | |

| Asset growth | −0.0010*** | −0.0010*** | −0.0028*** | −0.0031*** |

| (0.0001) | (0.0001) | (0.0006) | (0.0006) | |

| Z score | −0.0020*** | −0.0020*** | −0.0220*** | −0.0213*** |

| (0.0002) | (0.0002) | (0.0015) | (0.0016) | |

| GDP per capita | 0.0038*** | 0.0043*** | 0.0899*** | 0.1470*** |

| (0.0009) | (0.0009) | (0.0138) | (0.0161) | |

| GDP growth | −0.0075*** | −0.0081*** | −0.1636*** | −0.1911*** |

| (0.0007) | (0.0007) | (0.0081) | (0.0096) | |

| Financial freedom | −0.0020*** | −0.0021*** | −0.0013 | −0.0023 |

| (0.0002) | (0.0002) | (0.0014) | (0.0015) | |

| Boone indicator | −0.2173*** | −0.3294*** | −1.5281*** | −2.3443*** |

| (0.0505) | (0.0749) | (0.4157) | (0.5552) | |

| HHI | 0.0161 | 0.0534** | −0.5805*** | −0.4796*** |

| (0.0236) | (0.0260) | (0.1597) | (0.1734) | |

| Deposit money bank assets | −0.0017*** | −0.0017*** | −0.0034*** | −0.0043*** |

| (0.0001) | (0.0001) | (0.0007) | (0.0007) | |

| Stock market capitalization | −0.0016*** | −0.0017*** | −0.0022** | −0.0026*** |

| (0.0001) | (0.0001) | (0.0009) | (0.0010) | |

| Rule of law | 0.0589*** | 0.0793*** | 2.3798*** | 3.1476*** |

| (0.0198) | (0.0209) | (0.1980) | (0.2320) | |

| Crisis | 0.0282*** | 0.0266*** | 0.3715*** | 0.3282*** |

| (0.0030) | (0.0032) | (0.0297) | (0.0290) | |

| N | 123890 | 119548 | 131885 | 126728 |

| R2 | 0.087 | 0.089 | 0.099 | 0.106 |

Notes: This table shows the results of regressions as specified in model (2). All regressions are clustered at the bank level, with bank fixed effects. Year fixed effects are included when overhead costs is the dependent variable. The variable definitions and data sources are reported in Table 1. Standard errors are in parentheses, and *, **, and *** denote significance at the 10 %, 5 %, and 1 % levels, respectively.

4.3. Impact of bank globalization on efficiency in developed and developing countries

As argued earlier, the impact of bank globalization on efficiency could be different between developed and developing countries. We hypothesize that the impact is expected to more prominent in developing countries than in advanced economies. To investigate the potential heterogeneity, we rerun the regressions in Table 4, Table 5 separately for developed and developing countries and summarize the estimates in Table 6 . Since we are more interested in the impact of bank globalization on incumbent domestic banks, as well as for brevity, we only report the estimates for domestic banks. The conclusion is the same with all banks included, however.

Table 6.

Heterogeneous impacts of foreign bank entry on bank efficiency, by income group.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) | (11) | (12) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cost inefficiency | Cost inefficiency | Overhead costs | Overhead costs | Cost inefficiency | Cost inefficiency | Overhead costs | Overhead costs | Cost inefficiency | Cost inefficiency | Overhead costs | Overhead costs | |

| Developed countries | Developing countries | Developed countries | Developing countries | Developed countries | Developing countries | Developed countries | Developing countries | Developed countries | Developing countries | Developed countries | Developing countries | |

| Foreign bank numbers | 0.0088*** | 0.0004 | 0.0320*** | 0.0216** | ||||||||

| (0.0006) | (0.0011) | (0.0046) | (0.0089) | |||||||||

| Foreign bank assets | 0.0004 | 0.0022 | 0.0669*** | 0.0218** | ||||||||

| (0.0003) | (0.0014) | (0.0046) | (0.0106) | |||||||||

| Foreign claims | −0.0007*** | −0.0045*** | −0.0081*** | −0.0045 | ||||||||

| (0.0001) | (0.0014) | (0.0012) | (0.0168) | |||||||||

| N | 116020 | 2571 | 122606 | 2790 | 71571 | 1813 | 74896 | 1891 | 116961 | 2587 | 123922 | 2806 |

| R2 | 0.095 | 0.169 | 0.115 | 0.129 | 0.115 | 0.157 | 0.178 | 0.122 | 0.090 | 0.174 | 0.111 | 0.123 |

Notes: This table shows the results of the regressions as specified in model (2), with different subsamples. All regressions are clustered at the bank level, with bank fixed effects. Year fixed effects are included when overhead costs is the dependent variable. For brevity, the estimates for the control variables are not reported. The variable definitions and data sources are reported in Table 1. Standard errors are in parentheses, and *, **, and *** denote significance at the 10 %, 5 %, and 1 % levels, respectively.

Columns (1) to (8) of Table 6 show the regression results for the host-country effect and columns (9) to (12) those for the home-country effect. Consistent with Table 4, the positive coefficients for foreign bank numbers and assets indicate that foreign bank presence is associated with the lower efficiency of domestic banks. The magnitude and significance of these coefficients are higher for developed countries than for developing countries. As argued in Section 2, foreign bank entry could affect domestic banks in different ways. Foreign competition can pressure local banks to improve efficiency, but it can also incur more costs for domestic banks to stay viable, which causes inefficiency. In addition, the resource transfer effect helps domestic banks improve efficiency. The evidence presented so far suggests that the negative effect from foreign competition dominates the positive effects from foreign competition and resource transfer. Since the resource transfer effect is expected to be more prominent for developing countries than developed countries, it could offset more of the negative effect from foreign competition, which could be a plausible explanation for why foreign bank presence imposes less of a negative impact on bank efficiency in developing countries.

Consistent with Table 5, the negative coefficients for foreign claims in columns (9) to (12) in Table 6 suggest a positive impact of foreign expansion on bank efficiency at home. With cost inefficiency scores estimated with SFA, columns (9) and (10) seem to suggest that developing countries benefit more from efficiency gains from outward FDI in their banking sector. Nevertheless, with overhead costs as the proxy for cost inefficiency, evidence shows the opposite in columns (11) and (12), which renders inconclusive evidence.

4.4. Regulatory and institutional regimes and the impact of globalization on bank efficiency

The classification of developed and developing countries is based on per capita GDP only, but countries differ in many other aspects. In this section, we intend to examine how the regulatory and institutional regimes of a country affect the relationship between bank globalization and efficiency. As specified in model (3), the potential heterogeneity is reflected by the coefficients for the interaction terms.

Column (1) of Table 7 shows that foreign bank entry increases the cost inefficiency of the incumbent domestic banks in host countries, but this negative effect can be mitigated by stringent activity restrictions. Similarly, the negative coefficients for the interaction terms in columns (2) and (3) suggest that tight supervision with stronger supervision power by the authorities and multiple supervisors help alleviate the negative impact of foreign banks. As designed, variable limitations on foreign banks measure the number of activities that foreign banks can engage in, with higher values indicating fewer restrictions. The negative coefficients for the interaction terms in column (4) imply that fewer restrictions on foreign banks are associated with a low degree of efficiency loss with foreign bank entry. The evidence in column (5) suggests that with more applications to enter banking being denied, banks lose more efficiency when foreign banks enter the market. Regarding foreign bank assets, column (6) provides evidence that banks in a less competitive market suffer greater efficiency loss with a foreign presence. Column (7) indicates that banks lose less efficiency from foreign bank entry with greater financial freedom in the host countries. The results from columns (4), (5), and (7) are consistent with each other, all suggesting a banking market with a lower market entry barrier and fewer restrictions helps mitigate the negative effect of foreign entry. To save space, the estimates with overhead costs as the proxy for bank inefficiency are not presented here, but they depict the same evidence.

Table 7.

Regulatory and institutional regimes and the host-country effect of bank globalization.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cost inefficiency | Cost inefficiency | Cost inefficiency | Cost inefficiency | Cost inefficiency | Cost inefficiency | Cost inefficiency | |

| Foreign bank numbers | 0.0087*** | 0.0290*** | 0.0049*** | 0.0502*** | 0.0026*** | 0.0045*** | 0.0152*** |

| (0.0017) | (0.0030) | (0.0005) | (0.0060) | (0.0004) | (0.0004) | (0.0012) | |

| Foreign bank numbers × | |||||||

| Activity restrictions | −0.0006*** | ||||||

| (0.0002) | |||||||

| Supervision power | −0.0021*** | ||||||

| (0.0002) | |||||||

| Multiple supervisors | −0.0015 | ||||||

| (0.0009) | |||||||

| Limitations on foreign banks | −0.0120*** | ||||||

| (0.0015) | |||||||

| Applications denied | 0.0032** | ||||||

| (0.0016) | |||||||

| Boone indicator | −0.0011 | ||||||

| (0.0013) | |||||||

| Financial freedom | −0.0002*** | ||||||

| (0.0000) | |||||||

| N | 118675 | 118396 | 118675 | 118465 | 113009 | 118734 | 118748 |

| R2 | 0.110 | 0.113 | 0.109 | 0.115 | 0.119 | 0.109 | 0.113 |

| Foreign bank assets | 0.0053*** | 0.0241*** | 0.0040*** | 0.0270*** | 0.0021*** | 0.0016*** | 0.0120*** |

| (0.0008) | (0.0019) | (0.0006) | (0.0038) | (0.0003) | (0.0004) | (0.0011) | |

| Foreign bank assets × | |||||||

| Activity restrictions | −0.0007*** | ||||||

| (0.0001) | |||||||

| Supervision power | −0.0023*** | ||||||

| (0.0002) | |||||||

| Multiple supervisors | −0.0080*** | ||||||

| (0.0008) | |||||||

| Limitations on foreign banks | −0.0067*** | ||||||

| (0.0010) | |||||||

| Applications denied | 0.0056** | ||||||

| (0.0022) | |||||||

| Boone indicator | 0.0088*** | ||||||

| (0.0026) | |||||||

| Financial freedom | −0.0002*** | ||||||

| (0.0000) | |||||||

| N | 73492 | 73288 | 73492 | 73314 | 68479 | 73524 | 73538 |

| R2 | 0.129 | 0.133 | 0.131 | 0.131 | 0.118 | 0.128 | 0.131 |

Notes: This table displays the results of regressions as specified in model (3). All the regressions are clustered at the bank level, with bank fixed effects. For brevity, the estimates for the control variables are not reported. The variable definitions and data sources are reported in Table 1. Standard errors are in parentheses, and *, **, and *** denote significance at the 10 %, 5 %, and 1 % levels, respectively.

Table 8 shows that the home-country effect of bank globalization also depends on the home country’s regulatory and institutional regimes. With the two measures of cost inefficiency, the evidence shows that foreign expansion of the banking sector improves bank efficiency at home, but banks gain less efficiency if there are more restrictions on fee-generating activities (column (1)), fewer limitations on foreign banks (column (4)), and a lower degree of government interference (column (7)) in the banking sector. Although bank competition in the home country does not seem to matter in panel A, panel B does show that banks located in a less competitive banking market benefit more from foreign expansion (column (6)). In columns (2) and (3), more supervision power by the bank authorities tends to mitigate the positive impact of foreign expansion of the banking sector, whereas multiple supervisors tend to enhance it. The impact of applications denied is inconclusive, with opposite coefficients in the two panels.

Table 8.

Regulatory and institutional regimes and the home-country effect of bank globalization.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panel A | Dependent variable = cost inefficiency | ||||||

| Foreign claims | −0.0053*** | −0.0077*** | −0.0002 | −0.0102*** | −0.0003** | −0.0006*** | −0.0042*** |

| (0.0003) | (0.0006) | (0.0001) | (0.0037) | (0.0001) | (0.0001) | (0.0005) | |

| Foreign claims × | |||||||

| Activity restrictions | 0.0008*** | ||||||

| (0.0001) | |||||||

| Supervision power | 0.0006*** | ||||||

| (0.0001) | |||||||

| multiple supervisors | −0.0016*** | ||||||

| (0.0002) | |||||||

| Limitations on foreign banks | 0.0024*** | ||||||

| (0.0009) | |||||||

| Applications denied | 0.0042*** | ||||||

| (0.0005) | |||||||

| Boone indicator | 0.0003 | ||||||

| (0.0011) | |||||||

| Financial freedom | 0.0001*** | ||||||

| (0.0000) | |||||||

| N | 119603 | 119324 | 119603 | 119393 | 113833 | 119662 | 119676 |

| R2 | 0.093 | 0.092 | 0.090 | 0.091 | 0.108 | 0.089 | 0.090 |

| Panel B | Dependent variable = overhead costs | ||||||

| Foreign claims | −0.0150*** | −0.0677*** | −0.0049*** | −0.2148*** | −0.0044*** | −0.0083*** | −0.0561*** |

| (0.0020) | (0.0041) | (0.0010) | (0.0327) | (0.0010) | (0.0012) | (0.0047) | |

| Foreign claims × | |||||||

| Activity restrictions | 0.0014*** | ||||||

| (0.0003) | |||||||

| Supervision power | 0.0055*** | ||||||

| (0.0004) | |||||||

| multiple supervisors | −0.0091*** | ||||||

| (0.0018) | |||||||

| Limitations on foreign banks | 0.0538*** | ||||||

| (0.0082) | |||||||

| Applications denied | −0.0008 | ||||||

| (0.0040) | |||||||

| Boone indicator | −0.0234** | ||||||

| (0.0098) | |||||||

| Financial freedom | 0.0007*** | ||||||

| (0.0001) | |||||||

| N | 126801 | 126388 | 126801 | 126586 | 120988 | 126860 | 126874 |

| R2 | 0.102 | 0.106 | 0.102 | 0.114 | 0.114 | 0.102 | 0.107 |

Notes: This table displays the results of regressions as specified in model (3). All the regressions are clustered at the bank level, with bank fixed effects. Year fixed effects are included when overhead costs is the dependent variable. For brevity, the estimates for the control variables are not reported. The variable definitions and data sources are reported in Table 1. Standard errors are in parentheses, and *, **, and *** denote significance at the 10 %, 5 %, and 1 % levels, respectively.