Abstract

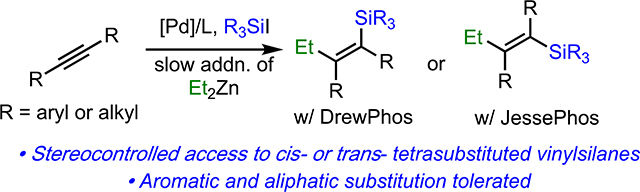

We report a palladium-catalyzed, three-component carbosilylation reaction of internal symmetrical alkynes, silicon electrophiles, and primary alkyl zinc iodides. Depending on the choice of ligand, stereoselective synthesis of either cis- or trans-tetrasubstituted vinyl silanes is possible. We also demonstrate conditions for the Hiyama cross-coupling of these products to prepare geometrically defined tetrasubstituted alkenes.

Graphical Abstract

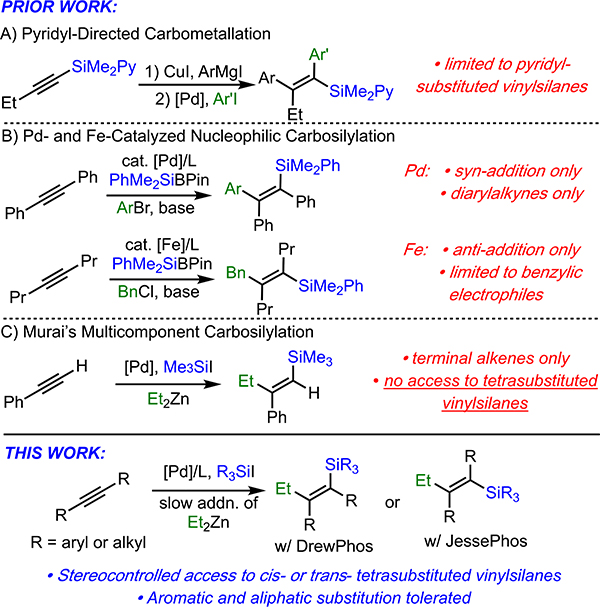

Vinylsilanes have a wide variety of applications in organic synthesis, including Hiyama cross-coupling reactions, Tamao-Fleming oxidations, and desilylative halogenations.1 Despite the development of numerous methods to prepare vinylsilanes,2 the stereocontrolled synthesis of tetrasubstituted vinylsilanes remains challenging. Classically, these highly substituted vinylsilanes have been prepared by the carbometallation of silylacetylenes; however, these methods typically require multiple steps, and often produce products with low E/Z selectivity.3 Only three examples of stereoselective tetrasubstituted vinylsilane synthesis are known. Itami has reported a copper-catalyzed single-pot carbometallation of pyridyl-substituted silylacetylenes.4 This method addresses stereocontrol in the carbometallation; however, it requires several steps to implement and is limited to the production of pyridyl silanes (Scheme 1A). In 2016, Shintani and Nozaki reported an elegant palladium-catalyzed tandem alkyne silylboration/Suzuki reaction that allows for net syn-carbosilylation of alkynes; however, this method is only effective for diarylalkynes (Scheme 1B).5 Most recently, Nakamura described a related iron-catalyzed method that, while effective for aliphatic alkynes, is limited to benzylic electrophiles and provides only the anti-addition products (Scheme 1B).6 Moreover, both of these latter methods require the use of nucleophilic silyl reagents, which can be challenging to access due to silicon’s low electronegativity.

Scheme 1.

Formation of Tetrasubstituted Vinylsilanes

In the early 1990’s, Murai reported the palladium-catalyzed carbosilylation of terminal alkynes using trimethylsilyl iodide and organometallic nucleophiles (Scheme 1C).7 This method is attractive because it takes advantage of silicon’s natural electrophilicity. However, Murai reported that the method did not work with internal alkynes, and thus did not allow access to tetrasubstituted vinylsilanes.

Based upon the continued need for simple protocols that can assess highly substituted vinylsilanes, as well as our ongoing interest in developing silyl-Heck-type reactions,8,9 we have reinvestigated the use of electrophilic carbosilylation for the preparation of tetrasubstituted vinylsilanes. Through identification of both the proper order of addition of reagents and the correct ligands, the stereoselective synthesis of syn- and anti- tetrasubstituted vinylsilanes via carbosilylation of internal alkynes is now possible. This method is applicable to both diaryl- and dialkyl-alkynes, as well as a variety of silyl functionalities, allowing for highly general access to tetrasubstituted vinylsilanes. Finally, we also report general conditions that allow for the tetrasubstituted vinylsilanes to undergo Hiyama-coupling, which also allows for facile synthesis of stereodefined tetrasubstituted alkenes.

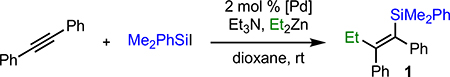

We began by reproducing the results reported by Murai, which involved the addition of the silyl iodide to a solution of Et2Zn and diphenylacetylene. In our case, however, we replaced Me3SiI with PhMe2SiI with an eye towards downstream functionalization.10 Consistent with Murai’s findings, only traces of the desired product were observed (Table 1, entry 1). Surprisingly, however, when the order of addition was switched and Et2Zn was added to a solution of alkyne and silyliodide, noticeably more product was formed (entry 2). As described by Murai, the major byproduct was phenyldimethylethylsilane resulting from alkylation of the silylhalide by Et2Zn. Murai suggested that this byproduct results from the direct reaction of the two reagents;7b however, control experiments in our lab revealed that this side reaction is also palladium-catalyzed.11 Combined, these results led us to investigate the slow addition of Et2Zn, which further improved the yield (entry 3). Extending the time of slow addition, in combination with switching the precatalyst to (PPh3)2PdCl2, the addition of Et3N to the solution,12 and adjustment of the stoichiometry resulted in nearly quantitative formation of the desired product (entries 4–6). Finally, to increase the utility of the method with more complex nucleophiles, we also investigated the use of alkylzinc halides as nucleophiles. This change resulted in an equally efficient reaction (entry 7). In all cases, only the product of syn-addition was observed.

Table 1.

Identification of Reaction Conditions for Diaryl Alkynes

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | [Pd] | Me2PhSiI (equiv) | Nucleophile (equiv) | Et3N (equiv) | Conditions | Yield 1 (%)a |

| 1 | Pd(PPh3)4 | 1 | Et2Zn (1) | 0 | Me2PhSiI added last, over 0.5 min | <1 |

| 2 | Pd(PPh3)4 | 1 | Et2Zn (1) | 0 | Et2Zn added last, over 0.5 min | 6 |

| 3 | Pd(PPh3)4 | 1 | Et2Zn (1) | 0 | Et2Zn added last, over 1 h | 25 |

| 4 | (Ph3P)2PdCl2 | 1 | Et2Zn (1) | 1 | Et2Zn added last, over 1 h | 70 |

| 5 | (Ph3P)2PdCl2 | 1 | Et2Zn (1) | 1 | Et2Zn added last, over 4 h | 89 |

| 6 | (Ph3P)2PdCl2 | 3 | Et2Zn (1.5) | 3 | Et2Zn added last, over 4 h | 95 |

| 7 | (Ph3P)2PdCl2 | 3 | EtZnI (1.5) | 3 | EtZnI added last, over 4 h | 95 |

Yield determined by GC.

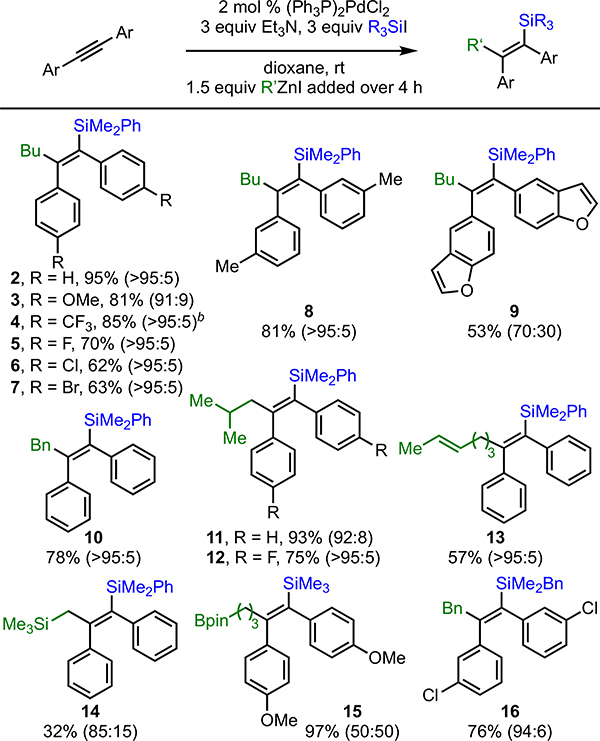

The scope of the reaction, with respect to diaryl acetylene, alkylzinc iodide, and iodosilane is broad (Scheme 2). High yields and outstanding syn-selectivity were generally observed. Functional group compatibility is also high, and includes aryl ethers (3), trifluoromethyl groups (4), aryl halides (5–7), heterocycles (9), increased steric bulk (8, 11, 12), alkenes (13), and alkyl boronic esters and silanes (14–15). As a general trend, lower syn-selectivity was observed with increased electron-density on the alkene β to silicon.13

Scheme 2.

Scope of Aryl-Substituted Vinylsilanes

aIsolated yields, syn/anti ratios (reported in parentheses) were determined by GC analysis of the crude reaction mixture. b((C6F5)P)2PdCl2.

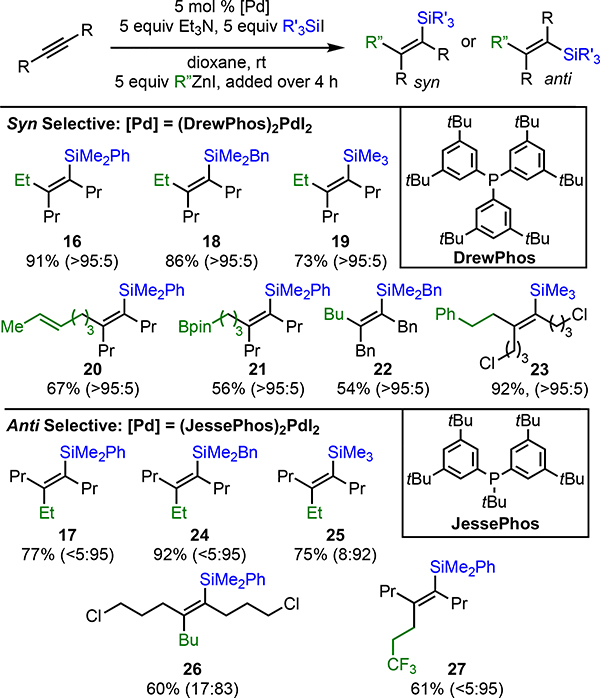

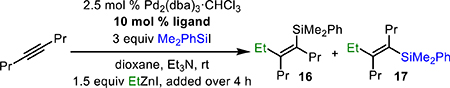

Our attention then turned to alkyl-substituted alkynes. We were initially disappointed to find that the conditions developed in Table 1 lead to poor syn/anti mixtures of products (Table 2, entry 1). To address this issue, we investigated the role of the ligand in stereoselection. Less electron-rich triarylphosphines gave poor reactivity (not shown). More electron-rich phosphines provided similar yield of product, but with low levels of selectivity (entry 2). Gratifyingly, however, we found that by using DrewPhos [(3,5-tBu2C6H3)3P],11a which features tert-butylated phenyl groups, dramatically improved selectivity for syn-addition product 16 was achieved (entry 3). Equally surprising, with even larger ligands, a reversal in selectivity was observed and anti-addition product 17 was observed as the major product (entry 4). Ultimately, JessePhos [(3,5-tBu2C6H3)2P(tBu)]8d proved superior in this regard, providing both high yield and outstanding selectivity for 17 (entry 5). Thus, depending upon the choice of ligand, either the syn- or anti-addition product can be selectively prepared.

Table 2.

Effect of Ligand on Selectivity of Alkyl-Substituted Vinylsilanes

| ||

|---|---|---|

| Entry | Ligand | Combined Yield and Ratio 16/17a |

| 1 | Ph3P | 88%, 65:35 |

| 2 | (4-OMeC6H4)3P | 66%, 60:40 |

| 3 | (3,5-tBu2C6H3)3P | 76%, 90:10 |

| 4 | (o-tol)3P | 65%, 18:82 |

| 5 | (3,5-tBu2C6H3)2P(tBu) | 67%, <5:95 |

Yields and syn/anti ratios determined by GC.

After additional optimization, which included use of preformed Pd(II)I2 precatalysts and adjustment of the stoichiometry,14 the scope of both the syn- and anti-selective conditions were explored (Scheme 3, top and bottom, respectively). Similar to the scope of the reaction with aryl-substituted alkynes, the reaction of alkyl-substituted alkynes was tolerant to a range of substitution on the silicon center (16–19, 24, 25). In addition, a range of functional groups were tolerated, including alkyl chlorides (23, 26), trifluoromethyl-groups (27), boronic esters (21), alkenes (20), and aromatic groups (22, 23).

Scheme 3.

Scope of Alkyl-Substituted Tetrasubstituted Vinylsilanesa

aIsolated yields, syn/anti ratios determined by GC analysis of the crude reaction mixture and reported in parentheses.

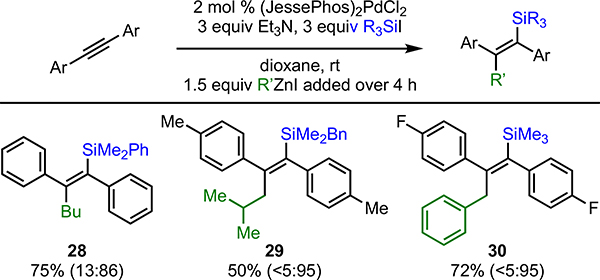

With the discovery that JessePhos leads to anti products, we also investigated its use in the carbosilylation of diarylalkynes. We found that (JessePhos)2PdCl2 is a suitable palladium precatalyst and leads to good yields of aryl-substituted tetrasubstituted vinylsilanes with excellent anti-selectivity (Scheme 4).

Scheme 4.

Anti-Addition of Aryl Alkynes

aIsolated yields, syn/anti ratios determined by GC analysis of the crude reaction mixture (reported in parenthesis).

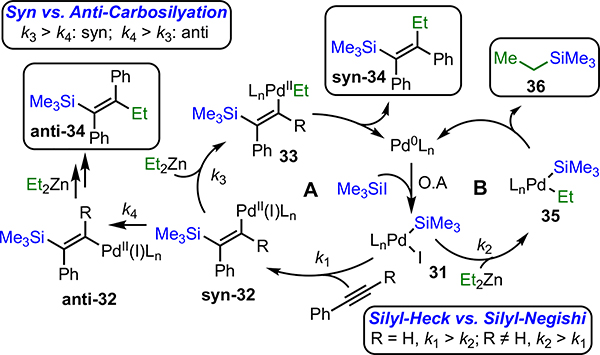

The newly discovered ability to prepare tetrasubstituted vinylsilanes using this method, particularly in the context of the earlier results reported by the Murai group, can be understood in the context of two competing silyl-Heck-like and silyl-Negishi reactions. Both proceed via oxidative addition of Pd(0) to the silyl halide. As proposed by Murai,7b the carbosilylation pathway (Figure 1, pathway A) proceeds via migratory insertion of the alkyne, transmetallation, and reductive elimination. With terminal alkynes, migratory insertion is evidently fast, and pathway A dominates. With internal alkynes, however, migratory insertion is slower, and direct transmetallation of the Pd(II)(SiR3)I (31) can compete. With high concentration of organometallic nucleophile, this latter pathway dominates, resulting in silyl-Negishi alkylation.11a However, by holding the concentration of the nucleophile low, the rate of transmetallation is suppressed and the carbosilylation pathway proceeds.

Figure 1.

Mechanistic Discussion

The ability to select syn- or anti-addition products based upon ligand appears to be predominately due to relative strength of the π-bond in intermediate 32. Electron-donors β to silicon are expected to weaken the bond. Simultaneously, larger ligands sterically destabilize this intermediate. When rupture of the π-bond (k4) is faster than transmetallation (k3), isomerization to the anti-product occurs.15

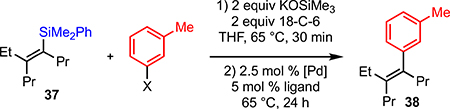

Lastly, we wished to demonstrate the utility of the tetrasubstituted vinylsilanes by converting them to stereodefined tetrasubstituted alkenes using a Hiyama reaction. Although Denmark’s tetrasubstituted vinylsilanolates can undergo cross-coupling,16,17 there is only a single example of a cross-coupling of a non-activated tetrasubstituted vinylsilane bearing all-carbon groups on silicon.18,19 Unfortunately, those conditions failed to result in cross-coupling of the tetrasubstituted vinylsilanes prepared in this study.14

Anderson has demonstrated that all-carbon-bearing trisubstituted vinylsilanes can undergo Hiyama coupling with aryl iodides in the presence of 18-crown-6 and KOSiMe3 using Pd2(dba)3 as the catalyst.20 Unfortunately, those conditions also failed to cross-couple the more substituted tetrasubstituted vinylsilanes (Table 3, entry 1). However, by combining the use of 18-crown-6 and KOSiMe3 with the use of SPhos as ligand (as identified in the Denmark studies),16,21 we were able to cross-couple both aryl iodides and aryl bromides in good yield (entries 2 and 3).14 As all-carbon-substituted vinylsilanes are easier to manipulate than the corresponding silanolates, these conditions should prove to be a useful advance in Hiyama cross-coupling.

Table 3.

Hiyama Cross-Coupling Conditions

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | X | [Pd] | Ligand | Yield (%) |

| 1 | I | Pd2(dba)3 | none | 0 |

| 2 | I | [(allyl)PdCl2 | SPhos | 50a |

| 3 | Br | [(allyl)PdCl2 | SPhos | 62b |

Yield determined by GC.

Isolated yield.

In conclusion, we have developed a three-component carbosilylation reaction for the synthesis of tetrasubstituted vinylsilanes directly from readily available or easily synthesized starting materials. This method allows for the formation of either the syn- or anti-addition vinylsilane products depending on the ligand choice. In addition, we have demonstrated the utility of the reaction through the development of a Hiyama cross-coupling reaction, which allows for the formation of stereodefined tetrasubstituted alkenes directly from these vinylsilane products. Current studies are focused on carbosilylation reactions on non-symmetric internal alkynes.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The University of Delaware and the National Science Foundation (CAREER CHE-1254360 and CHE-1800011) are gratefully acknowledged for support. S.B.P. thanks the NSF for a Graduate Research Fellowship (1247394). Gelest, Inc. (Topper Grant Program) is acknowledged for gift of chemical supplies. Data was acquired at UD on instruments obtained with the assistance of NSF and NIH funding (NSF CHE-0421224, CHE-0840401, CHE-1229234; NIH S10 OD016267, S10 RR026962, P20 GM104316, P30 GM110758).

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hiyama T; Oestreich M, Organosilicon Chemistry - Novel Approaches and Reactions. Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Lim DSW; Anderson EA, Synthesis of Vinylsilanes. Synthesis 2012, 44, 983–1010, 10.1055/s-0031-1289729; [DOI] [Google Scholar]; (b) Anderson EA; Lim DSW, Science of Synthesis. Thieme Chemistry: Stuttgart, 2015; Vol. 1, p 59. [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Negishi E, Controlled carbometalation as a new tool for carbon-carbon bond formation and its application to cyclization. Acc. Chem. Res. 1987, 20, 65–72, 10.1021/ar00134a004; [DOI] [Google Scholar]; (b) Snider BB; Karras M; Conn RSE, Nickel-catalyzed addition of Grignard reagents to silylacetylenes. Synthesis of tetrasubstituted alkenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1978, 100, 4624–4626, 10.1021/ja00482a066. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Itami K; Kamei T; Yoshida J. i., Diversity-Oriented Synthesis of Tamoxifen-type Tetrasubstituted Olefins. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2003, 125, 14670–14671, 10.1021/ja037566i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shintani R; Kurata H; Nozaki K, Intermolecular Three-Component Arylsilylation of Alkynes under Palladium/Copper Cooperative Catalysis. J. Org. Chem 2016, 81, 3065–3069, 10.1021/acs.joc.6b00587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Iwamoto T; Nishikori T; Nakagawa N; Takaya H; Nakamura M, Iron-Catalyzed anti-Selective Carbosilylation of Internal Alkynes. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2017, 56, 13298–13301, 10.1002/anie.201706333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.(a) Chatani N; Amishiro N; Murai S, A new catalytic reaction involving oxidative addition of iodotrimethylsilane (Me3SiI) to palladium(0). Synthesis of stereodefined enynes by the coupling of Me3SiI, acetylenes, and acetylenic tin reagents. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1991, 113, 7778–7780, 10.1021/ja00020a060; [DOI] [Google Scholar]; (b) Chatani N; Amishiro N; Morii T; Yamashita T; Murai S, Pd-Catalyzed Coupling Reaction of Acetylenes, Iodotrimethylsilane, and Organozinc Reagents for the Stereoselective Synthesis of Vinylsilanes. J. Org. Chem 1995, 60, 1834–1840, 10.1021/jo00111a048. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.(a) McAtee JR; Martin SES; Ahneman DT; Johnson KA; Watson DA, Preparation of Allyl and Vinyl Silanes by the Palladium-Catalyzed Silylation of Terminal Olefins: A Silyl-Heck Reaction. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2012, 51, 3663–3667, 10.1002/anie.201200060; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Martin SES; Watson DA, Preparation of Vinyl Silyl Ethers and Disiloxanes via the Silyl-Heck Reaction of Silyl Ditriflates. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2013, 135, 13330–13333, 10.1021/ja407748z; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) McAtee JR; Martin SES; Cinderella AP; Reid WB; Johnson KA; Watson DA, The first example of nickel-catalyzed silyl-Heck reactions: direct activation of silyl triflates without iodide additives. Tetrahedron 2014, 70, 4250–4256, 10.1016/j.tet.2014.03.021; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) McAtee JR; Yap GPA; Watson DA, Rational Design of a Second Generation Catalyst for Preparation of Allylsilanes Using the Silyl-Heck Reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2014, 136, 10166–10172, 10.1021/ja505446y; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) McAtee JR; Krause SB; Watson DA, Simplified Preparation of Trialkylvinylsilanes via the Silyl-Heck Reaction Utilizing a Second Generation Catalyst. Adv. Synth. Cat 2015, 357, 2317–2321, 10.1002/adsc.201500436; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Krause SB; McAtee JR; Yap GPA; Watson DA, A Bench-Stable, Single-Component Precatalyst for Silyl-Heck Reactions. Org. Lett 2017, 19, 5641–5644, 10.1021/acs.orglett.7b02807; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Vulovic B; Watson DA, Heck-Like Reactions Involving Heteroatomic Electrophiles. Eur. J. Org. Chem 2017, 2017, 4996–5009, 10.1002/ejoc.201700485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.(a) Also see: Hiroshi Y; Toshi-aki K; Teruyuki H; Masato T, Heck-type Reaction of lodotrimethylsilane with Olefins Affording Alkenyltrimethylsilanes. Chem. Lett 1991, 20, 761–762, 10.1246/cl.1991.761; [DOI] [Google Scholar]; (b) Matsumoto K; Huang J; Naganawa Y; Guo H; Beppu T; Sato K; Shimada S; Nakajima Y, Direct Silyl-Heck Reaction of Chlorosilanes. Org. Lett 2018, 20, 2481–2484, 10.1021/acs.orglett.8b00847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.The results reported in Table 1 are qualitatively identical with use of Me3SiI

- 11.(a) Cinderella AP; Vulovic B; Watson DA, Palladium-Catalyzed Cross-Coupling of Silyl Electrophiles with Alkylzinc Halides: A Silyl-Negishi Reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2017, 139, 7741–7744, 10.1021/jacs.7b04364; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Vulovic B; Cinderella AP; Watson DA, Palladium-Catalyzed Cross-Coupling of Monochlorosilanes and Grignard Reagents. ACS Catal 2017, 7, 8113–8117, 10.1021/acscatal.7b03465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.We are unsure of the role of Et3N in these reactions, but speculate that it might be involve in activating the silyliodide reagent towards oxidative addition by via formation of the silylammonium salt. See: Christenson B; Ullenius C; Hakansson M; Jagner S, Addition of Me2CuLi to enones and enoantes effects of solvent and additives on the yield and stereoselectivity. Tetrahedron 1992, 48, 3623–3632, 10.1016/S0040-4020(01)88500-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.In the case of 15, both the electron-richness of the alkyne starting material and the specific alkyl zinc iodide contribute to the low E/Z ratio. See result for 2 and Supporting Information.

- 14.See Supporting Information.

- 15.For a related proposal, see: Amatore C; Bensalem S; Ghalem S; Jutand A, Mechanism of the carbopalladation of alkynes by aryl-palladium complexes. J. Organomet. Chem 2004, 689, 4642–4646, 10.1016/j.jorganchem.2004.05.032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Denmark SE; Kallemeyn JM, Stereospecific Palladium-Catalyzed Cross-Coupling of (E)- and (Z)-Alkenylsilanolates with Aryl Chlorides. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2006, 128, 15958–15959, 10.1021/ja065988x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Also see: Li E; Zhou H; Östlund V; Hertzberg R; Moberg C, Regio- and stereoselective synthesis of conjugated trienes from silaborated 1,3-enynes. New J. Chem 2016, 40, 6340–6346, 10.1039/C6NJ01019A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Denmark SE; Liu JH-C, Sequential Silylcarbocyclization/Silicon-Based Cross-Coupling Reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2007, 129, 3737–3744, 10.1021/ja067854p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.For an example using internal carboxylate activation, see: Shindo M; Matsumoto K; Shishido K, Intramolecularly Activated Vinylsilanes: Fluoride-Free Cross-Coupling of (Z)-β-(Trialkylsilyl)acrylic Acids. Synlett 2005, 2005, 176–178, 10.1055/s-2004-836033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Anderson JC; Munday RH, Vinyldimethylphenylsilanes as Safety Catch Silanols in Fluoride-Free Palladium-Catalyzed Cross-Coupling Reactions. J. Org. Chem 2004, 69, 8971–8974, 10.1021/jo048746t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barder TE; Walker SD; Martinelli JR; Buchwald SL, Catalysts for Suzuki-Miyaura Coupling Processes: Scope and Studies of the Effect of Ligand Structure. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2005, 127, 4685–4696, 10.1021/ja042491j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.