Abstract

The observation that people with schizophrenia misattribute the source of their own actions has led to the hypothesis that they suffer from altered sensorimotor processes underlying sense of agency. Furthermore, rubber hand studies suggest an abnormal experience of embodiment in schizophrenia. However, this latter finding is based on a procedure that elicits ownership sensations for a fake hand by visuo-tactile stimulation, leaving the agency subcomponent of embodiment relatively untouched. By using a visuo-motor version of the embodiment illusion able to actively elicit also sense of agency for an alien hand, we tested whether the putative sensorimotor deficits are also involved in altering embodiment sensations in schizophrenia. Subjective (questionnaire) and perceptual (forearm bisection performance) indexes of the embodiment illusion were collected. Differently from controls, both the explicit agency component and the implicit body metrics update were not modulated by the extent of visuo-motor congruency in participants with schizophrenia. We conclude that motor prediction and/or temporal binding window impairments may alter the feeling of embodiment and body representation in schizophrenia.

Keywords: mirror box, multisensory, ownership, agency, rubber hand illusion, psychosis

Introduction

Embodiment is the sense of being located within own bodily boundaries and it is conceptualized as essentially stemming from 2 phenomenal experiences, ie, sense of ownership and sense of agency upon our own body. Sense of ownership is the conscious awareness that our body belongs to us. Sense of agency is the feeling of initiating and controlling a voluntary action and the sense of authorship over its consequences.1 The integration of coherent bodily related multisensory signals seems crucial for bodily experiences to arise.2

People with schizophrenia suffer from an altered sense of agency, especially those with passivity symptoms. They may feel as if an external agent drove and/or engendered their own actions and thoughts, eg, “I’m forced to walk around. I’m being made to turn right and left.”3 According to a classical model of schizophrenia,4,5 passivity stems from disturbances affecting central operations devoted to the monitoring and rapid correction of actions.6 This hypothesis is based on the premise that the brain predicts kinematic and sensory outcomes of the movement whenever a motor command is issued. Predictions are then contrasted with actual sensory feedback by comparator mechanisms. In case of matching, sensory attenuation7 and subjective sense of agency arise.4 Due to comparator model failure, delusional patients are prone to assign action authorship to external forces.8–10 Nonetheless, this model cannot fully account for patients’ tendency to self-attribute others’ movements in action recognition tasks.11–14 A line of reasoning suggests that this inconsistency (ie, hypoattribution vs overattribution of self-agency) is only apparent and it can be explained by the high variability affecting motor prediction computation.10,14 For instance, findings of Synofzik et al14 suggest that the disruption of internal cues (ie, motor prediction and/or proprioception) prompts perceptual system of people with schizophrenia to increase the weight of external cues about self-agency (eg, visual feedback), a fact accounting for overattribution of self-agency in action recognition tasks. The authors speculate that in case of external cues unavailability, patients might assume that external forces are causing or influencing their actions. In addition, Voss et al15 found that people with schizophrenia exhibit stronger intentional binding and overrely on the retrospective component of agency based on sensory reafference more than on predictive mechanisms.15

The sense of ownership in schizophrenia16–20 has been investigated by the rubber hand illusion (RHI).21 For the RHI to emerge, the participant looks at a rubber hand receiving repetitive tactile stimuli, while his own hand hidden from view is synchronously stimulated. This procedure induces a sense of embodiment of the fake hand and the localization bias of the real hand toward it (ie, proprioceptive drift). Overall, patients demonstrated a stronger RHI.16–19 In the study by Thakkar et al,18 patients referred more intense ownership for the fake hand than controls after both synchronous and asynchronous stimulation along with an enhanced proprioceptive drift after synchronous stimulation. According to the authors, the stronger RHI depends on the imbalanced interplay between multisensory integration and abnormally weak preexisting models of the body.18,22 Ferri et al,20 instead, observed that when the integration of actual visuo-tactile stimuli is ruled out (because tactile stimuli approach without touching the hand), patients declare lower RHI intensities than controls. In authors’ view, these results indicate that anticipation of sensory events is insufficient for the illusion to occur in patients and that the abnormal susceptibility to the classical RHI depends on altered integration of actual sensory information more than on defective prestored body representations.20

In general, RHI studies suggest more malleable body boundaries in schizophrenia. It is worth noting, however, that the RHI relies on visuo-tactile stimulation that mostly gives rise to ownership sensations, while influencing agency much less and possibly only indirectly as a carryover effect of ownership modulation. To the best of our knowledge, whether disrupted sense of agency (either hypoattribution or hyperattribution of self-agency) and related sensorimotor processes affect the embodiment illusion in participants with schizophrenia has not been investigated yet. Here, we employed a mirror box (MB)24 procedure in which participants observed the reflection of an experimenter's hand, mimicking the movements of their own hand, hidden behind the mirror. This procedure allows to directly investigate the contribution of not only sense of ownership but also sense of agency to the embodiment of an alien hand by manipulating the congruency between motor command and visual feedback. To probe the occurrence of the illusion, 2 measures were collected: the Embodiment questionnaire ratings, to assess conscious feelings of incorporation of the external limb,23 and the forearm bisection task,24–28 to quantify post-MB changes in the perception of limb extension. As concerns the latter task, previous studies brought evidence that body metric representation is malleable. The active training of the limb can modulate body metric representation inducing a shift of the estimation of the forearm midpoint toward the hand.24–28 Crucially, a recent study26 suggested that the update of body metric representation can occur even when one performs motor training while embodying another person’s hand by means of the MB. The rationale is that “E is embodied if and only if some properties of E are processed in the same way as the properties of one’s body” (p.84).29 In agreement with this definition, an MB training in poststroke patients induced an update of affected limb metrics perception as a plausible consequence of the embodiment of the mirrored image of the unaffected hand as if the impaired hand was able to move again.26,30

According to previous evidence, we expected healthy participants to show an elongation of the perceived limb length and stronger feelings of ownership and agency for the alien hand according to the strength of embodiment induced by the visuo-motor congruency experienced during the MB training. Conversely, because of the impairment in agency-related processes, participants with schizophrenia were expected to show an altered modulation of explicit as well as implicit indexes of embodiment.

Methods

Subjects

Thirty-one people presenting a diagnosis of schizophrenia were recruited from the outpatient community service ASST Fatebenefratelli—Sacco (Milan) and from Bolzano Hospital Mental Health department. Diagnosis for schizophrenia was made by treating psychiatrists and confirmed through the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR.31 Current severity of psychopathological symptoms was evaluated using the Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms and the Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms.32,33 All patients were receiving stable dose of antipsychotic medications at the time of the assessment. Two patients were excluded because they did not meet criteria for schizophrenia. Thirty-six healthy controls were enrolled by word of mouth and by the online recruitment system of Department of Psychology (University of Milano-Bicocca) (table 1).

Table 1.

Sample demographics

| Patients (n = 29) |

Controls (n = 36) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 41.34 (14.12) | 25.75 (7.86) |

| Sex, male/female | 18/11 | 6/30 |

| Handedness, right/left/ambidextrous | 25/3/1 | 31/5/0 |

| Education, years | 12,41 (2.83) | 15.44 (2.32) |

| SANS | ||

| Affective flattening | 3.28 (1.04) | — |

| Alogia | 2.90 (0.90) | — |

| Avolition—Apathy | 3.90 (0.81) | — |

| Anhedonia—Asociality | 3.92 (1.05) | — |

| Attention | 3.44 (1.23) | — |

| SAPS | ||

| Hallucinations | 1.65 (1.16) | — |

| Delusions | 2.06 (1.08) | — |

| Bizarre behavior | 2.90 (1.54) | — |

| Formal thought disorders | 2.30 (1.10) | — |

| Antipsychotic medication, type | ||

| First generation | 2 | — |

| Second generation | 26 | — |

| Both | 1 | — |

Note: Values are presented as n or mean (SD). SANS, Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms; SAPS, Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms.

The study was approved by the Ethical Committee of the University of Milano-Bicocca and by the Ethical Committees of Fatebenefratelli—Sacco Hospital (Milan) and of Bolzano Hospital. The study was carried out in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.34 All participants provided written informed consent.

Experimental Procedure

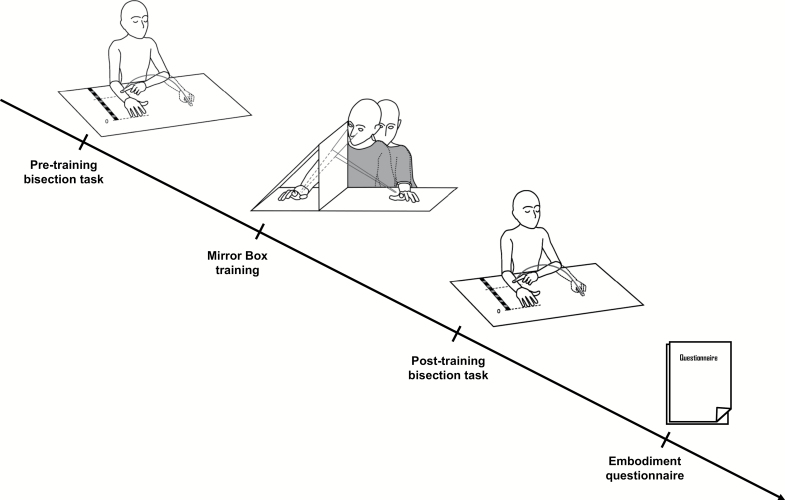

Participants underwent 3 experimental conditions, each one consisting of 4 phases (figure 1). Before starting the experiment, they were invited to remove bracelets and rings to enhance visual similarity between experimenter’s and participant’s limb during MB training. To avoid noisy tactile and proprioceptive clues during MB and bisection tasks, participants were often reminded to keep the tested limb still; once post-training bisection task ended, they could move their arm to restore baseline somatic feedback. The study was carried out by 2 experimenters. The first experimenter produced the movements that were reflected in the mirror and administered the questionnaire, while the second experimenter controlled for participants tapping at the proper rate during MB training and measured the endpoint of bisection trials.

Fig. 1.

Experimental procedure.

MB Training

After the pre-MB bisection task, participants were required to keep their eyes closed, to hold the upper limb (shortly before bisected) still on the table, and to put the other one under the table. The MB apparatus (ie, a triangle MB with a 60 × 50 cm reflective surface) was arranged so that the mirror was parallel to participant’s midsagittal plane and his/her limb was inside the MB. The experimenter sat near the participant, placing his limb on the table in order that its reflection matched the position of participant’s limb behind the mirror. To reduce visual interference due to the anatomical implausibility of the experimenter’s limb, a black cloth was draped onto participants’ trunk and experimenter’s shoulder.

During the training, participants had to raise and lower the index of the hidden hand for 1 min, following a metronome beating at 1 Hz. Meanwhile, they had to look at experimenter’s hand in the mirror. To reduce cutaneous inputs, they were instructed to avoid touching table surface with index finger.

Participants were exposed to 3 different types of (alien) visual feedback: (1) In-Phase: the experimenter tapped at the same frequency and in the same direction, ie, lowering the index at every beat; (2) In-Antiphase: the experimenter tapped at the same frequency but 180° out-of-phase, ie, raising the index at every beat; and (3) Random: the experimenter accomplished completely different finger movements, ie, following casual trajectories and irregular frequency. The order of conditions and hand laterality were counterbalanced across participants.

Bisection Task

In bisection task, participants were asked to arrange forearms in parallel position and to point at the middle of the tested limb with the contralateral hand. They were instructed to consider the limb length ranging from the elbow to the tip of the middle finger. Pointing movements had to be as straight as possible without online corrections once started.

Participants performed 10 pointing movements during each bisection task. As the task both preceded and followed each MB training, a total of 60 repetitions per subject were collected, ie, 10 trials × 2 bisection tasks (pre-MB, post-MB) × 3 conditions (In-Phase, In-Antiphase, Random). We measured both the subjective midpoint (ie, the distance between the middle fingertip and the point indicated by the subject) at each trial and the total length (ie, the distance between the middle fingertip and the olecranon). To normalize bisection estimates, the ratio between the 2 measures was calculated [R = subjective midpoint/total length].24

Questionnaire

At the end of each block, participants retrospectively rated their subjective experience during the MB training via a 27-item questionnaire. Statements were adapted from the RHI embodiment questionnaire.23 Particular attention was paid to the assessment of the Embodiment component of illusion and its subcomponents. Ownership items variously describe the feeling that the mirrored hand is likely to belong to one’s own body; Location items refer to a sense of spatial congruency between one’s own hand and the mirrored hand; Agency statements concern the sense of being the agent of the movements performed by the mirrored hand. For additional information, see supplementary material.

Participant had to verbally refer to what extent they agree/disagree with each statement by referring to a 7-point Likert scale presented on a sheet of paper (+3: strong agreement; 0: neither agreement nor disagreement; −3: strong disagreement). Items were read to participants and explained if needed.

To rule out participants’ response style effect, a within-subject standardization was adopted [Ipsatisation: y’ = (x-meanindividual)/SDindividual].35 Components scores were calculated from ipsatisation rates.

Data Analysis

Bisection R values were analyzed via linear mixed-effects model (lmer function; lme4 package36). Maximum Likelihood criterion was used to estimate fixed and random parameters, whereas models’ goodness of fit was compared by Likelihood Ratio test. Initially, a fixed intercept and by-subject random intercepts model was built to control for repeated-measure structure of data. To further specify random structure, Trial was entered as grouping factor and checked for model goodness-of-fit. Then, Group, Congruency, and Time of bisection task and their interactions were incrementally added as fixed effects and retained when they improved model goodness-of-fit. Lastly, a type III mixed-design ANOVA was executed on the final model.

Questionnaire scores relating to each component were analyzed through separate 2 (between-subject factor Group) × 3 (within-subject factor Congruency) ANOVAs for unbalanced data (aov_ez function; afex package37). Finally, an exploratory correlation analysis was computed between questionnaire components (mean scores calculated on raw data) and psychopathological scales. All data analyses were carried out in R environment.38

Results

Bisection Judgements

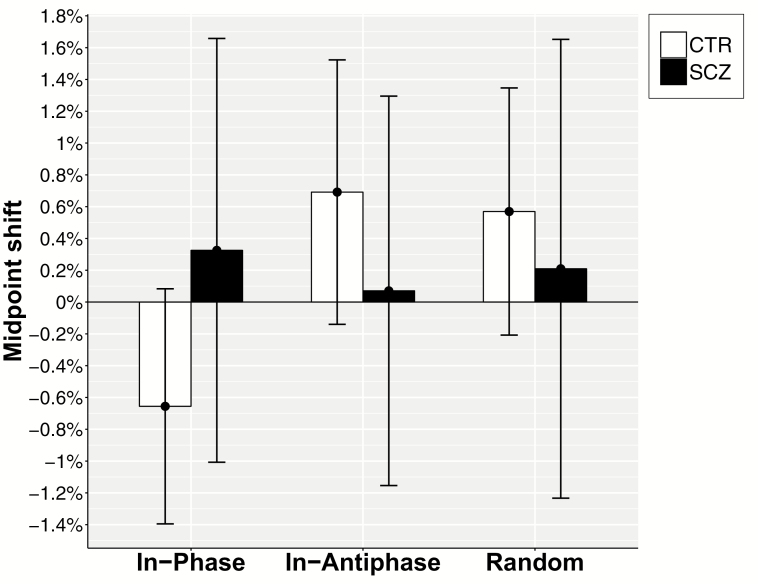

Bisection data were modeled as depending on all experimental predictors (fixed covariates: Group, Congruency, and Time) after adjusting for random effects Trial and Subject (see supplementary material). ANOVA run on the final model revealed significant differences for the 2-way interaction Group × Congruency [F2,3826.1 = 4.419; P = .012] and the 3-way interaction Group × Congruency × Time [F2,3826.1 = 4.562; P = .01]. Conversely, main effects Group [F1,65 = 0.595; P = .443], Congruency [F2,3826.1 = 2.392; P = .092], and Time [F2,3826.1 = 3.006; P = .083] and 2-way interactions Group × Time [F2,3826.1 = 0.001; P = .980] and Congruency × Time [F2,3826.1 = 2.496; P = .083] were not significant.

To examine the 3-way interaction, the mean post-MB midpoint displacement was calculated. Controls showed a distal shift equal to 0.66% [CI: −1.39; 0.08] after the In-Phase MB training but a proximal shift after both control conditions (In-Antiphase: 0.69% [CI: −0.14; 1.52]; Random: 0.57% [CI: −0.21; 1.35]). Patients displayed a less defined pattern, with a moderate proximal shift in all conditions (In-Phase: 0.33% [CI: −1.01; 1.66]; In-Antiphase: 0.07% [CI: −1.15; 1.30]; Random: 0.21% [CI: −1.23; 1.65]) (figure 2).

Fig. 2.

Post-MB forearm midpoint shift. Mean differences (±95% CI) between bisection performance before and after MB training. The shift is shown as percentage of the total forearm and hand length. Positive and negative values indicate a shift toward the elbow (proximal shift) and toward the hand (distal shift).

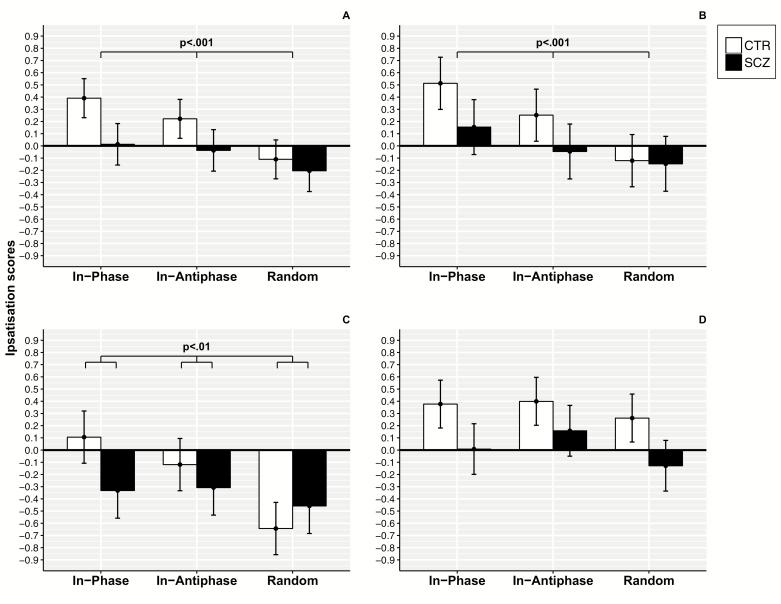

Questionnaire Responses

Significant effects were explored through graph inspection (figure 3). Ipsatisation makes between-group comparisons unreliable because adjusted scores represent deviations from the within-subject mean, which is 035; however, within-subject variance across conditions and interaction effects are not affected and reliably interpretable. Therefore, significant main effect Group will be mentioned but not commented on. The effect size statistics for between-within designs () will be provided (0.02: small, 0.13: medium, 0.26: large).39

Fig. 3.

Embodiment questionnaire ratings. Estimated marginal means of Embodiment (panel A), Ownership (panel B), Agency (panel C) and Location (panel D).

Embodiment: both main effects Group [F1,63 = 9.988; P = .002; = 0.06] and Congruency [F2,126 = 11.196; P < .001; = 0.09] were significant but not the interaction effect Group × Congruency [F2,126 = 1.691; P = .189; = 0.01]. Ownership: both the main effects Group [F1,63 = 3.891; P = .053; = 0.03] and Congruency [F2,126 = 12.760; P < .001; = 0.08] were significant but not the interaction effect Group × Congruency [F2,126 = 1.839; P = .163; = 0.01]. Agency: the main effect Group [F1,63 = 1.661; P = .202; = 0.01] was not significant, but the main effect Congruency [F2,126 = 11.899; P < .001; = 0.08] and the interaction effect Group × Congruency [F2,126 = 5.561; P = .005; = 0.04] were significant. Location: the main effect Group [F1,63 = 11.375; P = .001; = 0.08] was significant, but the main effect Congruency [F2,126 = 2.699; P < .071; = 0.02] and the interaction effect Group × Congruency [F2,126 = 0.388; P = .679; = 0.003] were not.

These results indicate that the general embodiment sensation and the feeling of ownership for the alien hand were driven by the degree of visuo-motor congruency in both groups: the higher the visuo-motor congruency, the higher the rates provided by subjects. Instead, sense of agency, which follows the extent of visuo-motor congruency in controls, stands on average at similar values across conditions in patients. For further results, see supplementary material.

Correlation Analysis

Correlation analysis suggests that hallucination severity moderately correlated with Ownership ( = .41, Puncorr = .026), Location ( = .41, Puncorr = .026), Agency ( = .43, puncorr = .021), and Movement ( = .38, Puncorr = .045) scores in Random condition. Location items related to In-Phase condition mildly correlated with alogia severity ( = .41, Puncorr = .029). For the entire correlation matrix, see supplementary material.

Discussion

In this study, we aimed to test the impact of sense of agency impairment on embodiment in people suffering from schizophrenia. The MB illusion specifically allowed to modulate the agency subcomponent of the bodily awareness in participants.

As expected, higher cross-modal congruency between sensory reafferent signals (ie, coherence between the visual feedback from the alien hand and the proprioceptive feedback from the participant’s hand) can evoke feelings of embodiment for the hand in the mirror in healthy people.40–43 This result also agrees with the proposal that the coherence between afferent and efferent information increases the likelihood that an extra-personal limb is tagged as “mine”,44 albeit obvious morphological differences. In the current study, when the alien hand kinematically mimicked participant’s hand movements, the visual feedback in the mirror could effectively approximate predictions. The generation of internal predictions is thought to enable the sensorimotor system to precisely anticipate temporal and postural parameters of the movement that is just about to be accomplished, crucially improving self-recognition.45 We suggest that an “inclusion” of the image of the alien limb within one’s own body representation may occur during the MB training.26,30 Specifically, the prolonged view of an alien hand moving in accordance with motor predictions would lead comparator mechanisms to embody it as a self-generated sensory feedback. The visual feedback provided by the alien hand might then be used by the motor system to feed up the dynamic short-term sensorimotor representations serving action program and guidance.29

Bisection data show that the strength of visuo-proprioceptive congruency also impacts on perceived body metrics. Indeed, the post-MB estimation of limb length increases/decreases along the forearm proximo-distal axis across conditions. The distal midpoint shift after the In-Phase condition replicates the study of Tosi et al,26 wherein hemiplegic patients showed an extension of the perceived length of the paretic limb induced by the motor training with MB. The bidirectional relocation of the subjective midpoint observed here is suggestive of a relative “elongation” of the limb representation, when embodiment of the alien hand occurs, but of a “shortening,” when embodiment is prevented. These effects are consistent with the hypothesis of plastic modifications of bodily representation serving motor control, ie, the body schema.46 We propose that post-MB bisection shifts may reflect top-down regulation of proprioception when body schema update is induced by the MB training. Otherwise stated, body schema may be subject to increased/reduced weighting of the hand segment representation as a result of the extent of visuo-motor congruency experienced during the MB training. Such an update may in turn induce an increased/reduced proprioceptive representation of the hand, as suggested by the distal and proximal shifts. This hypothesis agrees with the previously suggested dampening of proprioception following sensorimotor incongruency.42 Conversely, a mere effect of multiple muscles and joints activation and/or of the sustained visual attention on the hand can be ruled out because if this were the case, the midpoint shift would have been constantly distal across conditions.

Differently from controls, patients exhibited similar levels of agency across conditions. Consistently, bisection performance does not show a clear trend of proximo-distal modulation (see CI, figure 2). Overall, these results suggest that these aspects of the illusion are not driven by visuo-proprioceptive congruency in schizophrenia.

Two, not mutually exclusive, impairments might explain these findings. On the one hand, they might depend on the putative defective computation of motor predictions.47 Impaired predictions might have prevented the correct detection of kinematic similarities/dissimilarities in the mirrored hand, abolishing the modulation of the agency ratings across conditions. Furthermore, the high variance of bisection performance may support the hypothesis that internal motor prediction in schizophrenia is highly unreliable, as suggested by Synofzik et al.14 In this study, when asked to indicate the visual endpoint of pointing movements previously executed in the absence of visual feedback, patients demonstrated greater intertrial variability than controls. Given that endpoint estimation could be based on internal cues only, these results have been interpreted as a possible index of highly variable internal predictions.14 Accordingly, it is likely that the comparison between predicted and actual feedback, which would contribute to the inclusion of the alien hand within one’s own body schema, is also affected by high variability. As a result, the modulation of body metrics cannot clearly emerge. It is worth noticing, however, that other reasons for this high variability cannot be completely ruled out. For instance, the previously found link between passivity profile and body representation distortions.19,48 We carried out a posteriori analysis, dividing schizophrenia group according to passivity symptom severity. Nonetheless, an unclear trend of bisection performance still resulted, conceivably because of small subgroup size (supplementary material). Moreover, deficits of sustained attention in schizophrenia49 may play a role because fluctuations in the maintenance of the attentional focus on the mirrored hand may have altered embodiment processes.

A second potential explanation for the anomalous modulation of embodiment indexes is the width of the temporal binding window (TBW), ie, the time interval within which different sensory stimuli are very likely to be bound in the same percept. Prior work has shown wider visuo-proprioceptive TBW in schizophrenia12 with respect to healthy people.12,50,51 Therefore, lack of agency and bisection performance modulation might relate to lower multisensory temporal acuity. Interestingly, Ferri et al52 show that audio-tactile TBW, which is positively associated to the level of cognitive-perceptual schizotypy (an index of psychoses proneness), can be predicted by the temporal structure of spontaneous activity in auditory cortex. A causal link between temporal properties of resting-state neural fluctuations and multisensory TBW has been postulated in the “spatiotemporal” model of schizophrenia,53 which posits that the breakdown of intrinsic brain’s activity dynamics (both at spatial and temporal level) constitutes the neurobiological substrate of different psychopathological symptoms. In the case of ego disturbances (like agency disruption), the unbalance between the Default Mode Network, which is highly implicated in self-related processing, and Central Executive Network, conversely devoted to the processing of exogenous stimuli, would entail the pathological mixing of internally and externally oriented thoughts.53,54 Accordingly, reasons for the abnormal trend of bisection data and sense of agency might lie in the impairment of bottom-up sensory mechanisms and in the abovementioned impossibility to discretely distinguish between internal vs external perceptual contents. As regards correlation analysis, we avoided strong claims based on it given that it was mainly for exploratory purposes.

To conclude, this study yields 2 main findings. First, perceived body metrics bidirectionally update according to the strength of embodiment illusion, an effect that is compatible with an online reconfiguration of body schema. Second, patients did not demonstrate significant body metrics and sense of agency modulation, indicating that not only compromised visuo-tactile integration16–20 but also impaired visuo-motor integration may affect body representation building up in schizophrenia.

Funding

Università degli Studi di Milano-Bicocca (PhD grant to I.R.; FA-15311 to A.M. granted by the University of Milano-Bicocca).

Conflict of Interest statement

The authors have declared that there are no conflicts of interest in relation to the subject of this study.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Braun N, Debener S, Spychala N, et al. The senses of agency and ownership: a review. Front Psychol. 2018;9(535):1-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Azanõn E, Tamè L, Maravita A, et al. Multimodal contributions to body representation. Multisens Res. 2016. doi: 10.1163/22134808-00002531. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Waters FA, Badcock JC. First-rank symptoms in schizophrenia: reexamining mechanisms of self-recognition. Schizophr Bull. 2010;36(3):510–517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Frith CD, Blakemore SJ, Wolpert DM. Explaining the symptoms of schizophrenia: abnormalities in the awareness of action. Brain Res Rev. 2000;31(2-3):357-63. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0173(99)00052-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Frith C. Explaining delusions of control: the comparator model 20 years on. Conscious Cogn. 2012;21(1):52-4. doi: 10.1016/j.concog.2011.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wolpert DM, Ghahramani Z. Computational principles of movement neuroscience. Nat Neurosci. 2000;3 Suppl:1212–1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Blakemore SJ, Wolpert DM, Frith CD. Central cancellation of self-produced tickle sensation. Nat Neurosci. 1998;1(7):635–640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Blakemore SJ, Smith J, Steel R, Johnstone CE, Frith CD. The perception of self-produced sensory stimuli in patients with auditory hallucinations and passivity experiences: evidence for a breakdown in self-monitoring. Psychol Med. 2000;30(5):1131–1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Shergill SS, Samson G, Bays PM, Frith CD, Wolpert DM. Evidence for sensory prediction deficits in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(12):2384–2386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lindner A, Thier P, Kircher TT, Haarmeier T, Leube DT. Disorders of agency in schizophrenia correlate with an inability to compensate for the sensory consequences of actions. Curr Biol. 2005;15(12):1119–1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Daprati E, Franck N, Georgieff N, et al. Looking for the agent: an investigation into consciousness of action and self-consciousness in schizophrenic patients. Cognition. 1997;65(1):71-86. doi: 10.1016/S0010-0277(97)00039-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Franck N, Farrer C, Georgieff N, et al. Defective recognition of one’s own actions in patients with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158(3):454–459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Fourneret P, de Vignemont F, Franck N, Slachevsky A, Dubois B, Jeannerod M. Perception of self-generated action in schizophrenia. Cogn Neuropsychiatry. 2002;7(2):139–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Synofzik M, Thier P, Leube DT, Schlotterbeck P, Lindner A. Misattributions of agency in schizophrenia are based on imprecise predictions about the sensory consequences of one’s actions. Brain. 2010;133(Pt 1):262–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Voss M, Moore J, Hauser M, Gallinat J, Heinz A, Haggard P. Altered awareness of action in schizophrenia: a specific deficit in predicting action consequences. Brain. 2010;133(10):3104–3112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Peled A, Ritsner M, Hirschmann S, Geva AB, Modai I. Touch feel illusion in schizophrenic patients. Biol Psychiatry. 2000;48(11):1105-8. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3223(00)00947-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Peled A, Pressman A, Geva AB, Modai I. Somatosensory evoked potentials during a rubber-hand illusion in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2003;64(2-3):157-63. doi: 10.1016/S0920-9964(03)00057-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Thakkar KN, Nichols HS, McIntosh LG, Park S. Disturbances in body ownership in schizophrenia: evidence from the rubber hand illusion and case study of a spontaneous out-of-body experience. PLoS One. 2011;6(10):e27089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Graham KT, Martin-Iverson MT, Holmes NP, Jablensky A, Waters F. Deficits in agency in schizophrenia, and additional deficits in body image, body schema, and internal timing, in passivity symptoms. Front Psychiatry. 2014;5:126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ferri F, Costantini M, Salone A, et al. Upcoming tactile events and body ownership in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2014;152(1):51-7. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2013.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Botvinick M, Cohen J. Rubber hands “feel” touch that eyes see. Nature. 1998;391(6669):756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Klaver M, Dijkerman HC. Bodily experience in schizophrenia: factors underlying a disturbed sense of body ownership. Front Hum Neurosci. 2016;10:305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Longo MR, Schüür F, Kammers MP, Tsakiris M, Haggard P. What is embodiment? A psychometric approach. Cognition. 2008;107(3):978–998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sposito A, Bolognini N, Vallar G, Maravita A. Extension of perceived arm length following tool-use: clues to plasticity of body metrics. Neuropsychologia. 2012;50(9):2187–2194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Garbarini F, Fossataro C, Berti A, et al. When your arm becomes mine: pathological embodiment of alien limbs using tools modulates own body representation. Neuropsychologia. 2015;70:402–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Tosi G, Romano D, Maravita A. Mirror box training in hemiplegic stroke patients affects body representation. Front Hum Neurosci. 2018;11(617):1-10. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2017.00617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. D’Angelo M, di Pellegrino G, Seriani S, Gallina P, Frassinetti F. The sense of agency shapes body schema and peripersonal space. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):13847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Romano D, Uberti E, Caggiano P, Cocchini G, Maravita A. Different tool training induces specific effects on body metric representation. Exp Brain Res. 2019;237(2):493–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. de Vignemont F. Body schema and body image–pros and cons. Neuropsychologia. 2010;48(3):669–680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Romano D, Bottini G, Maravita A. Perceptual effects of the mirror box training in normal subjects. Restor Neurol Neurosci. 2013;31(4):373–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW.. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders Research Version, Patient Edition with Psychotic Screen (SCID-I/P); New York: Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Andreasen N. The Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS). Iowa City: University of Iowa;1984. doi: 10.4236/oalib.1100693. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Andreasen NC. Scale for the assessment of negative symptoms (SANS): : conceptual and theoretical foundations. Br J Psychiatry Suppl. 1989;7:49-58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. World Medical Organization. Declaration of Helsinki. BMJ. 1996;313:1448–1449. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Fischer R, Milfont TL. Standardization in psychological research. Int J Psychol Res. 2010;3(1):88-96. doi: 10.21500/20112084.852. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Bates D, Sarkar D. lme4: Linear Mixed-Effects Models Using S4 Classes.2006. http://cran.r-project.org. Accessed August 30, 2017.

- 37. Singmann H, Bolker B, Westfall J, Aust F. afex: Analysis of Factorial Experiments. R package version 0.18-0. 2017. https://cran.r-project.org/package=afex. Accessed November 7, 2017.

- 38. R Development Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2016. doi: 10.1038/sj.hdy.6800737. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Bakeman R. Recommended effect size statistics for repeated measures designs. Behav Res Methods. 2005;37(3):379–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Holmes NP, Snijders HJ, Spence C. Reaching with alien limbs: visual exposure to prosthetic hands in a mirror biases proprioception without accompanying illusions of ownership. Percept Psychophys. 2006;68(4):685–701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. McCabe CS, Haigh RC, Halligan PW, Blake DR. Simulating sensory-motor incongruence in healthy volunteers: implications for a cortical model of pain. Rheumatology. 2005;44(4):509-16. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keh529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Medina J, Khurana P, Coslett HB. The influence of embodiment on multisensory integration using the mirror box illusion. Conscious Cogn. 2015;37:71–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Romano D, Caffa E, Hernandez-Arieta A, Brugger P, Maravita A. The robot hand illusion: inducing proprioceptive drift through visuo-motor congruency. Neuropsychologia. 2015;70:414–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Apps MA, Tsakiris M. The free-energy self: a predictive coding account of self-recognition. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2014;41:85–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Tsakiris M, Haggard P, Franck N, Mainy N, Sirigu A. A specific role for efferent information in self-recognition. Cognition. 2005;96(3):215–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Berlucchi G, Aglioti SM. The body in the brain revisited. Exp Brain Res. 2010;200(1):25–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. van der Weiden A, Prikken M, van Haren NE. Self-other integration and distinction in schizophrenia: a theoretical analysis and a review of the evidence. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2015;57:220–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Graham-Schmidt KT, Martin-Iverson MT, Holmes NP, Waters F. Body representations in schizophrenia: an alteration of body structural description is common to people with schizophrenia while alterations of body image worsen with passivity symptoms. Cogn Neuropsychiatry. 2016;21(4):354–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Hoonakker M, Doignon-Camus N, Bonnefond A. Sustaining attention to simple visual tasks: a central deficit in schizophrenia? A systematic review. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2017;1408(1):32–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Ismail MAF, Shimada S. “Robot” hand illusion under delayed visual feedback: relationship between the senses of ownership and agency. PLoS One. 2016;11(7):e0159619. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0159619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Shimada S, Qi Y, Hiraki K. Detection of visual feedback delay in active and passive self-body movements. Exp Brain Res. 2010;201(2):359-64. doi: 10.1007/s00221-009-2028-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Ferri F, Nikolova YS, Perrucci MG, et al. A neural “Tuning Curve” for multisensory experience and cognitive-perceptual schizotypy. Schizophr Bull. 2017;43(4):801–813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Northoff G, Duncan NW. How do abnormalities in the brain’s spontaneous activity translate into symptoms in schizophrenia? From an overview of resting state activity findings to a proposed spatiotemporal psychopathology. Prog Neurobiol. 2016;145–146:26–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Robinson JD, Wagner NF, Northoff G. Is the sense of agency in schizophrenia influenced by resting-state variation in self-referential regions of the brain? Schizophr Bull. 2016;42(2):270–276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.