Abstract

Nonmarket strategy – strategic actions directed at influencing the governmental, legalregulatory, and societal environment of business – is a key factor in an airlines' competitive position yet remains relatively under-analyzed in aviation research. The COVID-19 crisis has created a heightened role for nonmarket strategy and our paper argues that in deciding how to respond to a variety of policy measures introduced by governments, airline executives need to take into account the perceived legitimacy from the flying public of their response to governments. Our paper presents an integrative framework to analyze airlines' nonmarket response to COVID-19 governmental policy measures. Using a two-by-two matrix, we identify key conceptual links between industry's nonmarket response, the health impacts of a given policy measure as well as its economic costs for the airlines. Our study concludes that, unless economic stakes in a given policy measure are high, airlines do not risk active bargaining with governments over the content of that measure. Such bargaining could trigger a delegitimation cascade: a self-reinforcing process in which key stakeholders reassess their view of airlines' conduct and the industry's broader societal impact. Bargaining is pursued when economic impacts of policy measures are high, and in that case, the choice between cooperative and adversarial posture towards the government depends on the health impact of a given policy.

Keywords: COVID-19, Legitimacy, Airlines, Nonmarket strategy, Bargaining

Highlights

-

•

Airline executives need to take into account the perceived legitimacy of their response to COVID-19.

-

•

We identify four distinct nonmarket strategic options for airlines in response to governments.

-

•

We link those options with both a health impact felt by society and an economic impact felt by the airlines themselves.

-

•

Bargaining with governments runs a risk of triggering a delegitimation cascade.

1. Introduction

Few sectors have been as negatively impacted by the COVID-19 crisis as the airline industry. As this Special Issue suggests, the response set for airline executives is extensive and comprises numerous issues at strategic, tactical and operational levels (Zenker and Kock, 2020). To contribute to the conceptual and prescriptive discussion over the industry's response, our paper focuses on one specific aspect of the COVID-19 response set for airlines that has hitherto been overlooked by the emerging research on this topic – namely nonmarket strategy. This is salient because of the profound public policy impact that responses to COVID-19 are exerting worldwide. Scholars, executives and policymakers can all benefit from a clearer framing of the nonmarket options they face. This paper provides such a novel, integrative strategic framing that complements technical analyses of pandemics on airline operations as well as assessments of economic impacts of the latter on countries generally and the industry specifically.

A concept first introduced by economist Albert Hirschman, (1958), nonmarket strategy has been used by strategy and international business scholars since the late 1980s (Boddewyn, 1988; Baron, 1995). It came to be understood as a broad, integrative term for corporate strategic actions directed at governmental, legal-regulatory, political, and social environments of business. Bach and Allen (2010, 41) describe this concept as follows: “Nonmarket strategy starts with a simple, dual premise — first, that issues and actors ‘beyond the market’ increasingly affect the bottom line, and, second, that they can be managed just as strategically as conventional ‘core business’ activities within markets.” The COVID-19 crisis illustrates starkly that scholarly interest in nonmarket strategies has been well founded. It is clear that the broad array of governmental policies introduced in response to the pandemic have become the single most important factor determining the business future of even the most competitive airlines.

The nonmarket strategy literature suggests that there are two broad categories of nonmarket strategic initiatives that executives can choose to pursue. On one hand, there are so-called bargaining strategies, where executives explicitly or implicitly engage powerful governmental, political or societal actors to pursue public policy outcomes beneficial to firms. Bargaining strategies cover a broad array of approaches that vary in terms of the mutual attitude of firms and governmental/societal actors (the so-called “conflictual” and “partnership” bargaining nonmarket strategies; Boddewyn and Brewer, 1994) as well as the time horizon over which engagement is being conducted (the so-called “transactional” and “relational” bargaining nonmarket strategies; Hillman and Hitt, 1999). Examples of bargaining strategies include lobbying, campaign contributions, engagement and negotiations with advocacy and NGOs groups, neo-corporatist dialog through industry chambers or tripartite commissions, arbitration and litigation as well as illegal corruption.

Nonbargaining approaches stand in contrast to bargaining strategies. They are a set of initiatives focusing on interactions with the firm's nonmarket environment that does not involve direct engagement with political or social actors. Compliance with governmental regulations, business reconfiguration in response to those regulations (De Villa et al., 2018), selective avoidance of regulations or engagement in corporate social responsibility initiatives are all examples of nonbargaining nonmarket strategies.

In a classic study, Baron (1995) emphasized that key to competitive success lies at aligning its market strategy with its nonmarket strategy. In a COVID-19 world, the airline industry will have to intensify such integration. In particular, sensitivity towards health and safety issues underlying governmental policies will force airlines to pursue nonbargaining nonmarket approaches on some issues, while more traditional economic issues will continue to attract robust bargaining and advocacy. In the remainder of our paper we explore the reasons for why nonmarket choices may vary depending on the policy issue at hand. Key to our analysis is the concept of legitimacy of a business entity. Using that concept, we offer an integrative framework for balancing market and nonmarket considerations in response.

2. COVID-19: Nonmarket impacts on the airline industry

The significance of the nonmarket environment that the airline industry must confront in a COVID-19 world is difficult to overestimate. Terry (2020) observes that decisions and actions that governments and regulators take during COVID-19 will affect the duration and gravity of the crisis; speed of recovery from it and the extent of industry transformation. How governments intervene in the sector will create winners and losers among airlines – reshaping the competitive landscape under which they will compete in the years ahead.

The impact is particularly profound because while governments are providing airlines with financial carrots, they come with particularly costly sticks. In the short run, the latter include the impact of lockdowns and border closures (discussed in more detail in the next section). In the medium term, the public health and hygiene regulations imposed or contemplated by governments may be dramatic. For example, a report by the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (2020) urged airlines to practice distancing, hand hygiene, respiratory etiquette, use of medical face masks, and to require passengers to declare their COVID-19-related status before receiving boarding permission. In the US, Baldwin (2020) reports that Delta Airlines uses a “fogging process” used in many health-care facilities while American Airlines and United Airlines indicated they are using high-grade disinfectants and multipurpose cleaners on all touch points on aircraft. Aircraft that remain overnight at an airport receive an enhanced cleaning procedure. Last but not least, Emirates prototyped pre-flight COVID-19 tests on-site at Dubai airport, which provide results within 10 min. The airline requires its crew to wear personal protective equipment (PPE) and passengers to wear masks (Werner, 2020).

Just as these costly mandates are implemented, important governments are also extending unprecedented levels of financial support to the distressed industry. Europe's largest carrier group, Lufthansa German Airlines agreed on a state bailout worth €9 billion (USD 9.9 billion) that grants the German Federal government a 20 percent stake in the airline group which in turn gives it two seats on the supervisory board allowing it to exercise its voting rights in exceptional circumstances, such as to protect the firm against a takeover ("Lufthansa in 'advanced talks' over coronavirus bailout" 2020). As we discuss below in part three, this bailout package came after considerable bargaining between the senior executives and federal government officials. France and the Netherlands will provide a bailout of 10.2 billion euros, (USD10.8 billion), to rescue Air France-KLM. One of Europe's biggest airline groups, it will receive a €4 billion bank loan backed by the French state and a €3 billion direct government loan (Alderman, 2020). British Airways, part of International Airlines Group (IAG) that includes American Airlines, Iberia and Vueling accessed a GBP300 million (USD 371 million) government loan from the Bank of England's Coronavirus Corporate Finance Facility (CCFF) in the second week of April 2020. Fonte (2020) reports that the Italian government will provide around 3 billion euros (USD 3.2 billion) of fresh capital into Alitalia leading to its renationalization. Table 1 below outlines selected bailout packages as of end of June 2020 of European carriers.

Table 1.

Financial Support offered to European Airlines in response to COVID-19 as of end June 2020.

| Airline | Amount (€ mn) | Status (June 26, 2020) | Type of Support |

|---|---|---|---|

| Air Baltic | 250 | Agreed | Recapitalization |

| Air France-KLM Group | |||

| Air France | 7000 | Agreed | Loan and Loan Guarantee |

| KLM | 3200 | Agreed | Loan and Loan Guarantee |

| Alitalia | 3000 | Awaiting Parliamentary approval | Nationalization |

| Condor | 550 | Agreed | Loan |

| EasyJet UK | 670 | Agreed | Loan |

| Finnair | 826/414 | Agreed/Under discussion | Credit guarantee and Recapitalization |

| International Airlines Group (IAG) | |||

| British Airways | 343 | Agreed | Loan |

| Iberia | 750 | Agreed | Loan |

| Vueling | 260 | Agreed | Loan |

| Lufthansa Group | |||

| Lufthansa German Airlines | 9000 | Agreed | Loan and equity stake |

| Austrian Airlines | 450 | Agreed | State Aid and Loan tied partially to meeting CO2 reduction and other climate mitigation efforts |

| Swiss International Airlines | 1200 | Agreed | Loan and no dividend payments during duration of loan |

| Brussels Airlines | 290 | Under discussion | Unknown |

| Nordica | 30 | Agreed | Recapitalization |

| Norwegian Express | 277 | Agreed | Loan Guarantee |

| Regional Carriers in Norway | 121 | Agreed | Loan Guarantees |

| Ryanair | 670 | Agreed | Loan |

| SAS | 407 | Agreed | Credit Guarantee |

| All airlines operating in Sweden | 318 | Agreed | Loan Guarantees |

| TAP Portugal | 1200 | Agreed | Loan |

| TUI Group | 1800 | Agreed | Loan and no dividend payments during duration of loan |

| TUI Fly | 250 | Under discussion | No clarity |

| Virgin Atlantic | 573 | Under discussion | Loan and credit guarantees |

| Wizzair | 344 | Agreed | Loan |

Source: authors' own adapted from https://www.transportenvironment.org/what-we-do/flying-and-climate-change/bailout-tracker. June 26, 2020.

At the same time, US carriers (American Airlines, Delta Air Lines and United Airlines) are all beneficiaries of a USD 25 billion government rescue package appropriated by US Congress (Young, 2020). The largest low-cost carrier (LCC) in the US, Southwest Airlines, will receive more than USD 3.2 billion, made up of USD 2.2 billion in direct payroll support and a USD 1 billion unsecured ten-year term loan with low interest rates (Otley, 2020).

With the exception of Etihad, the Middle East carriers Emirates, Qatar Airways and Turkish Airlines are all recipients of state aid. Narayanan and Nair (2020) report that Emirates is in talks to raise billions of USD in loans from local and international banks, on top of Dubai's state bailout, which remains undisclosed, for the world's largest long-haul airline carrier. Nicholson (2020) details that while Qatar Airways positioned itself as the airline to ‘get people home’ during COVID-19, it has been operating some flights at 50 percent occupancy. This has led to calls for financial support from the CEO of Qatar Airways. Lastly, Turkish Airlines will receive unspecified funds from the Turkish government as part of national COVID-19 stimulus package (Airline Economics, 2020).

Interestingly, three of Europe's largest LCCs (EasyJet, Ryanair and Wizzair) have attempted to play the state aid issue both ways. When European governments announced large financial bailouts for their national carriers, they initially opposed them. Saeed (2020) reports that by the end of the summer 2020, Ryanair may file between 10 and 15 cases with the EU. Derrick (2020) also details similar dissent from Wizzair executives. Yet by end of April 2020, Wizzair announced that it has received confirmation that it was an eligible issuer under the UK Government's Covid Corporate Financing Facility (CCFF) and that Ryanair had raised GBP 600 m (USD 750 m) from the same facility (Caswell, 2020). Last but not least, Easyjet was reported by Laville (2020) to have received similar sums as Ryanair from the UK government.

3. COVID-19: Market impacts on the airline industry

The extant literature has considered the impacts of public health emergencies and pandemics on the aviation sector. In particular they emphasize the centrality of actions and processes introduced in aviation on the spread of viruses. For example, Gold et al. (2019) examined the screening strategies employed by airlines during a pandemic. They found that exit screenings were very effective in reducing the spread of the virus during air travel. In a similar vein Nikolaou and Dimitriou (2020) used an epidemiological simulation modelling exercise to look how European airports play a central role in the spread of COVID-19 globally. Based on the experience of previous pandemics to impact the industry, Chung (2015) observes that there is an inherent tension between public health demands and the financial sustainability of aviation that comes from restrictions imposed by measures to control pandemics. It creates the need for and a space in which compromises between governments and airlines are reached.

Thus, it is not by accident that our discussion of the strategic landscape facing the industry started by focusing on the nonmarket aspect. Indeed, the scale of the above-mentioned nonmarket impacts on the airline industry makes it difficult to even conceptualize the purely commercial challenges of the industry; almost all of these challenges are related, at least indirectly, to the public policy response to COVID-19. The catastrophic drop in air travel in the spring of 2020 is a perfect case in point. Its swiftness was undoubtedly the result of widespread lockdowns, quarantines and border closures imposed by governments. Carter (2020) describes data from April 2020 that shows that the number of flights dropped by almost 80 percent globally and more than 90 percent in Europe compared to 2019. In the U.S. the number of passengers screened by the United States Transportation Security Administration dropped from about 2.5 million passengers per day to between 130,000 and 215,000 passengers during the first week of May 2020. As lockdowns are slowly lifted since the start of June 2020, passenger numbers still remain at a fraction of what they were before COVID-19.

The economic devastation for the airline industry is manifest. International Civil Aviation Organization data indicate that there has been an overall reduction of between 33 and 60 percent of seats offered by airlines. This implies an overall reduction of 1878 to 3227 million passengers leading to a forecasted loss of approximately USD 244bn to USD 420bn of gross operating revenues of airlines (International Civil Aviation Organization, 2020). By May 2020, five commercial airlines had gone bankrupt (FlyBe (UK); Avianca (Colombia); Compass Airlines (US); Virgin Australia; Transtate Airlines US) (Slotnick, 2020). It is expected that around USD 200bn worth of state aid worldwide will be made available by governments to support the industry and prevent further insolvency (Ramsey, 2020). Table 2 below details European insolvencies as of the end of June 2020.

Table 2.

European airline insolvencies by end June 2020.

| Airline | Country | Status | With Effect From |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ernest Airlines | Italy | Ceased operations/company voluntary arrangement | February 19, 2020 |

| Atlas Global | Turkey | Ceased operations/filed for bankruptcy | February 14, 2020 |

| Air Italy | Italy | Ceased operations/in liquidation | February 26, 2020 |

| FlyBe | UK | Ceased operations/in administration | March 5, 2020 |

| LEVEL Europe | Austria | Ceased operations/filed for insolvency | June 18, 2020 |

| SunExpress Deutschland | Germany | Ceased operations/plans liquidation | June 23, 2020 |

| City Jet | Ireland | In Examinership/Still currently operating | April 17, 2020 |

Source: authors' own adapted from Centre for Aviation data.

As the initial wave of lockdowns is eased, the mid-to-long term market impacts becomes more evident. A combination of COVID-19 infectiousness and serious symptoms will have a lasting impact on the preferences and choices of both business and leisure fliers. Traveler behavior towards flying by plane could transform substantially as passengers realize that despite boarding a sanitized aircraft, the epidemiological risk of being infected in a pressurized cabin at ten thousand meters altitude is undeniable. During the H1N1 epidemic, the World Health Organization (World Health Organisation, 2009) identified that the virus could be spread up to two rows ahead and two rows behind an infected passenger. Seabra et al. (2013) examined perceived risks of international travel from pandemics and terrorist events and assessed risk perception patterns across countries. Respondents suggested that as far as health and personal safety were concerned, they regarded as a legitimate expectation that travel organizations should assure this before they travel. A recent study by Union Bank of Switzerland (UBS) suggests that air travel in the EU and China could be reduced as passengers switch from air to rail travel (UBS, 2020). COVID-19 concerns seem also to be converging with climate change concerns around flying. Current disruption to air travel is an occasion for passengers to shape their travel behaviors beyond the pandemic (Badstuber, 2020). Overall, there is an undeniable and legitimate concern in society that shapes airlines’ nonmarket response to COVID-19. We now turn to this issue.

4. Linking Market and Nonmarket: The legitimacy perspective

So far, we have outlined both the market and nonmarket challenges faced by the airline industry in a COVID-19 world. While the core advice of strategic management scholarship is that a firm's responses to market and nonmarket challenges should be aligned with each other, how such alignment is arrived at is not always clearly spelled out. We fill this gap with the help of the concept of legitimacy. Viewed as “a pivotal but often confusing construct in management theory” (Suddaby et al., 2017, 451), legitimacy has been defined in numerous ways. Perhaps the most influential of these definitions considers legitimacy as “a generalized perception or assumption that the actions of an entity are desirable, proper, or appropriate within some socially constructed system of norms, values, beliefs, and definitions” (Suchman, 1995, 574). Suddaby, Bitektine, and Haack (2017) point out that dominant understanding sees legitimacy as an intangible strategic asset built up by conforming with societal and industry-specific norms and expectations (see also Deephouse, 1996). Boddewyn (1995) points out that compliance with government-imposed legal and regulatory standards is an important source of legitimacy.

Suddaby et al. (2017) also observe that legitimacy can be viewed as continuous process of legitimation and delegitimation. Legitimacy thus understood is a generalized, collective perception composed of subjective judgments of a firm by its key stakeholders (customers, shareholders, journalists etc.). Tost (2011) uses advances in neuroscience to describe the process in which an individual with a stable judgement about legitimacy of a particular firm moves on to reassess this judgment. The author points out that such a “mental alarm” that makes individuals reassess their judgement concerning legitimacy of a given firm is most often caused by so-called jolts. Jolts are both systemic “major events […] disturbing the functioning of the field” (Tost, 2011, 700) but also more micro-level experiences of “a dramatic violation of expectations” of a given firm (Tost, 2011, 701). The author also points out that “the mental alarm is more likely to be activated” if the event in question invites a switch between positive and negative legitimacy judgement” (Id.).

As far as the airline industry is concerned, the COVID-19 pandemic falls well within the definition of the macro-level legitimacy jolt. The sudden cessation of almost all air travel, and the persistent sense of risk and uncertainty concerning travel in general, in itself creates fertile ground for broad segments of the flying public to rethink their judgments concerning the legitimacy of the airline industry. Against the background of shaken expectations and taken-for-granted beliefs, a single micro-level event showing airlines as not sufficiently committed to the maintenance of highest standards for health and safety of the flying public may trigger what Kuran and Sunstein (1998, 683) dubbed “an availability cascade [:] a self-reinforcing process of belief formation by which an expressed perception triggers a chain reaction that gives the perception increasing plausibility through its rising availability in public discourse.” Airlines and their executives should be well aware about the risk of evoking such a “delegitimation cascade” in which key stakeholders quickly reassess their view of airlines conduct and its broader social impact.

5. Airline Nonmarket strategy in a COVID-19 context

The COVID-19 pandemic has created a period of legitimacy volatility for the airline industry. Since, as mentioned above, the perceived compliance with both governmental regulations and societal norms are important sources of continuous legitimacy, airline executives may be particularly cautious about defying those norms and regulations. At the same time, the same health crisis brought unprecedented economic pressures on the industry. This creates a powerful counterincentive to passive compliance with particularly costly and disruptive measures.

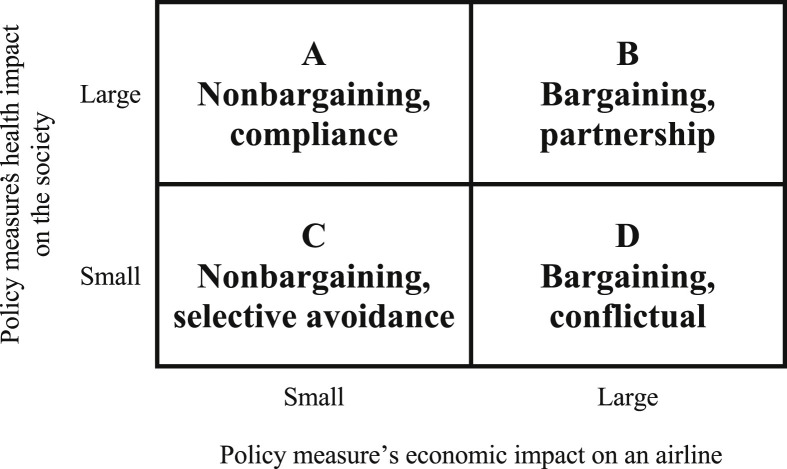

The balance between the desire to avoid a “delegitimation cascade” on one hand and immediate economic pressures on the other determines the nonmarket strategic choices that airlines will make in response to proposed new governmental actions and policy measures during the COVID-19 pandemic. Fig. 1 presents the resulting palette of nonmarket options. The industry response depends on the size of the health impacts on society of a particular policy measure proposed by a government as well as on economic impacts of a given measure on airlines.

Fig. 1.

Nonmarket strategic approaches of airlines in response to governmental Covid-19 measures.

Let's discuss the resulting nonmarket options for the industry. If a given policy measure would have relatively insignificant economic impact on the industry but large health impact on the flying public (quadrant A), the concerns about continuous legitimacy of the industry will take precedence over economic pressures. This results in nonbargaining nonmarket strategy, focused on passive compliance with governmental mandates or even more proactive Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) measures going beyond of government mandates. Examples include rapid introduction of low touch processes and social distancing measures at check-in and boarding as well as thorough cleaning of aircraft (Grant, 2020). In those situations, noncompliance could logically and quickly trigger a major health incident (such as a publicized case of mass infection), acting as a legitimacy jolt for the already anxious flying public. In that case, more active bargaining with governments over the proposed measures would risk creating a perception that the industry is not living up to its responsibilities in a COVID-19 world.

A second case concerns measures where both health and economic impacts are small (quadrant C). The dominant nonmarket strategy is also nonbargaining, but in this case focused on selective avoidance. In this case, airline executives may not want to aggressively bargain over a proposed regulation. The low economic impact at stake does not justify taking the risk of creating a negative perception of the industry's attitude. As the risk of a major health incident resulting from non-compliance is also relatively small, airlines have few incentives to comply to the letter. Airlines may agree in principle to make the cabins as hygienic as possible but may be unwilling to remove seat back pockets or add Perspex dividers between seats (Garcia, 2020). As new realities set in, we expect this category to expand. Note that in cases of rules with low health impact, authorities have little incentive to extensively monitor compliance.

The third situation is where both health impact on the public and the economic impact on the airline is large (quadrant B). This situation presents the greatest challenge for airlines executives. Compliance with the proposed measure significantly adds to financial stress on the industry. Given the large health impact of the measure in question, non-compliance or even a perception that the airline is pushing back against the safety measure may trigger a delegitimation cascade for the airlines. We expect the industry to engage in bargaining with political actors over the final shape of the measure, but to do it in a conciliatory, “partnership” manner (Boddewyn and Brewer, 1994). Airlines accept the legitimate concerns of society around safeguarding health but engage governments in bargaining over how to achieve the broadly accepted objective. For instance, eliminating the middle seat in an economy class row or de-densifying the cabin by taking out seat rows or leaving them empty was initially considered by numerous regulators as a necessary safety precaution. The industry never questioned the objectives of the policy but bargained with governments to find a less costly solution (e.g. requiring facemasks for passengers and PPE for cabin crew). This option prevailed, following intensive lobbying by IATA, the global industry association (Lillit, 2020).

The last category on our strategic map concerns policy measures with high economic impact on the airlines but low health impact on the public (quadrant D). Here economic considerations prevail over worries about delegitimation. The strategy of choice for airlines will be conflictual bargaining with political actors, with airline executives driving a hard bargain with governments on economic support. The classic argument at an airline's disposal is ‘too big to fail’. It is legitimate for governments (and society) to bail airlines out, otherwise the cost of travel will rise once routes are cut after insolvency (Gurdus, 2020). Since airlines know that the government has an interest in bailing them out, they can bargain hard over the details of the quid pro quo. Carsten Spohr, Lufthansa Group CEO, summed up this strategy in blunt terms: “We were hit by this crisis, which is not our fault. We need government support. We do not need government management” (Horton, 2020). His airline was losing 1 million euro per day at the time of the statement. Three weeks later, the European Commission agreed in principle to allowing the German aid but requested that the airline surrender a number of slots. This led to the Heinz Hermann Thiele, an industrialist controlling 15 percent of Lufthansa stock, to reject the offer fearing stock dilution should the German federal government take a 20 percent stake. Only after considerable cajoling from the Lufthansa Group Management Board, unrelated to the stock dilution concern, did he relent (Ziady, 2020). Another example of the same strategy is the hard opposition of LCCs to the bailouts of the traditional carriers. Executives such as Ryanair's Michael O'Leary had few qualms about loudly protesting governmental subsidies and bailouts that, in his view, create an uneven playing field (Saeed, 2020).

Similarly, in June 2020, three major airlines – British Airways, Easyjet and Ryanair – sued the UK government over a sweeping policy that mandates 14-day quarantine on every person arriving to the United Kingdom. As predicted by our model, the airlines quite readily agreed with an earlier version of the policy that imposed quarantine on people from high risk countries. (Milligan et al., 2020). That policy was still be very costly, but its health impact was unambiguously large. A significant inflow of travelers from countries with high infection rates would quickly trigger serious health incidents. But the blanket inclusion of countries that have much lower infection rate than Britain itself manifestly is not going to have a significant impact on public health. Indeed, in their lawsuit, the airlines asked the judge precisely for a scientific review of the health impact of the indiscriminate quarantine order. The airlines may be reasonably confident in the outcome of such an review given the statement of Patrick Vallance, the Chief Scientific Adviser to the UKs government, who admitted in June 2020 that quarantine was most effective where Britain had few cases of coronavirus and other countries had higher rates of infection” (Parker and Plimmer, 2020).

6. Conclusion

By focusing on the nonmarket aspects of COVID-19 analyzed in this paper, we offer a novel contribution to the debate over its impact and why airlines and governments respond in the way they do. At a time of unprecedented financial peril for the airline industry caused by COVID-19, senior executives are having to make critical choices about how they align their market strategy with their regulatory position to secure survival.

Current and emerging research has focused understandably on both operational, technical and broader economic impacts of COVID-19 on the airline industry. Our paper suggests that these impacts and the choices made by airline executives and public policymakers in response are intimately framed by the perceived legitimacy of their actions by the flying public. Using the concept of business legitimacy, we have offered an integrative strategic framework mapping the options available to airlines as they respond to a host of governmental policy measures. Drawing on early evidence, we tie these options to health impact on society of a given measure and economic impact felt by the airlines themselves.

We show that by engaging in bargaining with governmental and societal actors over COVID-19 policy measures, airlines run the risk of triggering a self-reinforcing delegitimation cascade. This risk is for airlines only if economic stakes of a policy measure are high leading to risk mitigation by airlines through engaging in conciliatory bargaining when a policy measure is significant for public health. In case of policy measures that are of low economic impact, airlines will not risk the perception of being less than committed to the wellbeing of the flying public and would not engage in bargaining with governments. They will comply faithfully, or even exceed governmental mandates, if non-compliance would carry a risk of a major health incident. In other cases, they will selectively avoid compliance.

Viewed through the lens of COVID-19, our analysis suggests important research questions about nonmarket strategy that should form a basis for future research. This includes the following: does legitimacy vary depending on the nature of political systems (democracy v. authoritarian) in which airlines operate? Are nonmarket choices made by airlines constrained by the nature of their business models i.e. full-service carriers v. LCCs? Do we observe variations in the nonmarket choices made by airlines as a function of their ownership structure (state ownership, privately held or publicly traded)? Is there is an identifiable link between the nature of organizational culture and nonmarket strategy choices?

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jairtraman.2020.101867.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- Airline Economics State aid for airlines – the story so far. 2020. https://www.aviationnews-online.com/airline/state-aid-for-airlines-the-story-so-far/

- Alderman Liz. New York Times; 2020. Air France-KLM Gets €10 Billion Bailout as Coronavirus Hits Travel.https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/25/business/air-france-klm-bailout.html Apr. 25, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bach David, Allen David. What every CEO needs to know about nonmarket strategy. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2010;51(3):41. [Google Scholar]

- Badstuber Nicole. Guardian; 2020. Flights Are Grounded – Is This the Moment We Give up Our Addiction to Flying?https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2020/apr/09/flights-are-grounded-is-this-the-moment-we-give-up-our-addiction-to-flying Apr. 9, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin Shawn. CNBC.com; 2020. What Airlines Are Doing to Clean Their Planes.https://www.cnbc.com/2020/04/02/how-do-american-united-and-delta-clean-their-airplanes-amid-covid-19.html Apr. 2, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Baron David P. Integrated strategy: market and nonmarket components. Calif. Manag. Rev. 1995;37(2):47–65. http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=buh&AN=9504072292&site=ehost-live [Google Scholar]

- Boddewyn Jean J. Political aspects of MNE theory. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 1988;19(3):341–363. doi: 10.2307/155130. http://www.jstor.org/stable/155130 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boddewyn Jean J. The legitimacy of international-business political behavior. Int. Trade J. 1995;9(1):143–161. [Google Scholar]

- Boddewyn Jean J., Brewer Thomas L. International-business political behavior: new theoretical directions. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1994;19(1):119–143. doi: 10.5465/amr.1994.9410122010. http://amr.aom.org/content/19/1/119.abstract [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carter Jamie. Forbes; 2020. Future Air Travel Is ‘Touchless’ yet Terrifying: Fewer Flights, Sudden Border Closures, No Movies.https://www.forbes.com/sites/jamiecartereurope/2020/05/11/the-future-of-travel-is-touchless-yet-terrifying-with-fewer-flights-last-minute-border-closures/ May 11, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Caswell Mark. BusinessTraveller.com; 2020. Ryanair Forecasting 74 Million Drop in Passenger Numbers in FY21.https://www.businesstraveller.com/business-travel/2020/05/18/ryanair-forecasting-74-million-drop-in-passenger-numbers-in-fy21/ (blog). May 18. [Google Scholar]

- Chung Lap Hang. Impact of pandemic control over airport economics: reconciling public health with airport business through a streamlined approach in pandemic control. J. Air Transport. Manag. 2015;44:42–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jairtraman.2015.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Villa, Maria A., Rajwani Tazeeb, Lawton Thomas C., Mellahi Kamel. To engage or not to engage with host governments: corporate political activity and host country political risk. Global Strategy Journal. 2018;9(2):208–242. [Google Scholar]

- Deephouse David L. Does isomorphism legitimate? Acad. Manag. J. 1996;39(4):1024–1039. doi: 10.2307/256722. http://www.jstor.org/stable/256722 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Derrick Emily. SimpleFlying.com (blog); 2020. Wizz Air CEO Not Happy with State Aid for Airlines.https://simpleflying.com/wizz-air-state-aid/ Apr. 3. [Google Scholar]

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control . Mare. 23 2020. Considerations Relating Social Distancing Measures in Response to COVID-19. Brussels. [Google Scholar]

- Fonte Giuseppe. Reuters.com; 2020. Italy to Inject 3 Bln Euros in New Alitalia.https://www.reuters.com/article/italy-alitalia-minister/update-1-italy-to-inject-3-bln-euros-in-new-alitalia-minister-idUSL8N2CP4B6 [Google Scholar]

- Garcia Marisa. Runway Girl Network (blog); 2020. Industry Stakeholders Weigh Likelihood of Major Cabin Reconfigurations.https://runwaygirlnetwork.com/2020/05/08/industry-stakeholders-weigh-likelihood-of-major-cabin-reconfigurations/ May 8. [Google Scholar]

- Gold Lukas, Balal Esmaeil, Horak Tomas, Cheu Ruey Long, Mehmetoglu Tugba, Gurbuz Okan. Health screening strategies for international air travelers during an epidemic or pandemic. J. Air Transport. Manag. 2019;75:27–38. doi: 10.1016/j.jairtraman.2018.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant Martin. Forbes; 2020. Delta Air Lines Changes Boarding Procedure to Accommodate Social Distancing.https://www.forbes.com/sites/grantmartin/2020/04/12/delta-air-lines-changes-boarding-procedure-to-accommodate-social-distancing/ Jun. 3, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Gurdus Lizzy. CNBC.com; 2020. These Two Airlines Are ‘too Big to Fail,’ Investor Says.https://www.cnbc.com/2020/04/02/american-airlines-coronavirus-downgrade-airline-stock-2020-outlook.html Apr. 2, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hillman Amy J., Hitt Michael A. Corporate political strategy formulation: a model of approach, participation, and strategy decisions. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1999;24(4):825–842. doi: 10.5465/amr.1999.2553256. http://amr.aom.org/content/24/4/825.abstract [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hirschman Albert. Yale University Press; New Haven: 1958. The Strategy of Economic Development. [Google Scholar]

- Horton Will. Forbes; 2020. Lufthansa CEO Argues Bailout Conditions: ‘Nobody Wants the State at the Helm of Lufthansa.https://www.forbes.com/sites/willhorton1/2020/05/05/lufthansa-ceo-argues-bailout-conditions-nobody-wants-the-state-at-the-helm-of-lufthansa/ May 5, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- International Civil Aviation Organization 2020. Economic impacts of COVID-19 on Civil aviation. May 10, 2020. https://www.icao.int/sustainability/Pages/Economic-Impacts-of-COVID-19.aspx

- Kuran Timur, Sunstein Cass R. Availability cascades and risk regulation. Stanford Law Rev. 1998;51(4):683–768. https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.journals/stflr51&i=695 https://heinonline.org/HOL/PrintRequest?handle=hein.journals/stflr51&collection=journals&div=30&id=695&print=section&sction=30 [Google Scholar]

- Laville Sandra. The Guardian; 2020. Coronavirus: Airlines Seek €12.8bn in Bailouts without Environmental Conditions Attached.https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/apr/22/airlines-seek-128bn-in-coronavirus-bailouts-without-environmental-conditions-attached Apr. 22, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Lillit Marcus. CNN.com; 2020. IATA Backs Face Masks but Not Middle Seat Closures for Post-coronavirus Air Travel.https://edition.cnn.com/travel/article/iata-middle-seats-face-masks-coronavirus-intl-hnk/index.html May 7, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Lufthansa in 'advanced talks' over coronavirus bailout Deutsche Welle. 2020. https://www.dw.com/en/lufthansa-in-advanced-talks-over-coronavirus-bailout/a-53523170 May 21, 2020.

- Milligan Ellen, Browning Jonathan, Siddharth Vikram Philip. Bloomberg.com; 2020. Airlines Challenge U.K.’s Quarantine to Boost Travel Market.https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-04-05/emirates-airline-said-to-seek-billions-of-dollars-in-bank-loans Jun. 12, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Narayanan Archana, Nair Dinesh. Bloomberg.com; 2020. Emirates Airline Seeks Billions in Loans after Virus Hit.https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-04-05/emirates-airline-said-to-seek-billions-of-dollars-in-bank-loans Apr. 20, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson Dylan. World of Aviation (blog); 2020. Qatar Airways Seeking Bailout Despite Continuing Flights.https://worldofaviation.com/2020/03/qatar-airways-seeking-bailout-despite-continuing-flights/ Jun 1. [Google Scholar]

- Nikolaou Paraskevas, Dimitriou Loukas. Identification of critical airports for controlling global infectious disease outbreaks: stress-tests focusing in Europe. J. Air Transport. Manag. 2020:101819. doi: 10.1016/j.jairtraman.2020.101819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otley Tom. Business Traveller (blog); 2020. These Airlines Have Received a Bailout.https://www.businesstraveller.com/features/these-airlines-have-received-a-bailout/ May 21. [Google Scholar]

- Parker George, Plimmer Gill. Financial Times; 2020. UK Quarantine Regime Begins Despite Airlines' Opposition. Jun. 8 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ramsey Malcolm. 2020. Airlines: Financial Eporting Implications of COVID-19 KPMG. [Google Scholar]

- Saeed Saim. Politico.eu; 2020. Ryanair Goes to War against Coronavirus Bailouts.https://www.politico.eu/article/ryanair-goes-to-war-against-coronavirus-bailouts/ May 12, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Seabra Cláudia, Dolnicar Sara, Abrantes José Luís, Kastenholz Elisabeth. Heterogeneity in risk and safety perceptions of international tourists. Tourism Manag. 2013;36:502–510. [Google Scholar]

- Slotnick David. Some of the world's airlines could go bankrupt because of the COVID-19 crisis. Business Insider. 2020 https://www.businessinsider.com/coronavirus-airlines-that-failed-bankrupt-covid19-pandemic-2020-3?r=DE&IR=T May 12, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Suchman Mark C. Managing legitimacy: strategic and institutional approaches. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995;20(3):571–610. [Google Scholar]

- Suddaby Roy, Bitektine Alex, Haack Patrick. Legitimacy. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2017;11(1):451–478. [Google Scholar]

- Terry Bryan. 2020. COVID-19: Rising to the Challenge with Resilience in the Airline Sector. Apr. 3, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Tost Leigh Plunkett. An integrative model of legitimacy judgments. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2011;36(4):686–710. [Google Scholar]

- UBS By train or by plane? Traveller's dilemma after COVID-19, amid climate change concerns. 2020. https://www.ubs.com/global/en/investment-bank/in-focus/2020/by-train-or-by-plane.html Apr. 2.

- Werner Laurie. Forbes; 2020. Emirates Airlines Tests Passengers for COVID-19 Pre-flight.https://www.forbes.com/sites/lauriewerner/2020/04/15/emirates-airlines-tests-passengers-for-covid-19-pre-flight/ Jun. 2, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organisation . May 13 2009. WHO Technical Advice for Case Management of Influenza A(H1N1) in Air Transport. Geneva. [Google Scholar]

- Young Sarah. Reuters.com; 2020. British Airways Owner Bets on Costs Not Bailouts to Survive.https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-iag/british-airways-owner-bets-on-costs-not-bailouts-to-survive-idUSKCN22B0UQ Apr. 29, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Zenker Sebastian, Kock Florian. The coronavirus pandemic–A critical discussion of a tourism research agenda. Tourism Manag. 2020;81:104164. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2020.104164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziady Hanna. CNN Business; 2020. 'We Simply Don't Have Any money.' Lufthansa Shareholders Approve $10 Billion Bailout.https://edition.cnn.com/2020/06/24/business/lufthansa-bailout-heinz-hermann-thiele/index.html June 25, 2020. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.