Abstract

The number of elderly patients with cancer has increased due to aging of the population. However, safety of programmed cell death-1 (PD-1) or programed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1) inhibitors in elderly patients remains controversial, and limited information exists in frail patients. The present study retrospectively identified 197 patients treated with nivolumab, pembrolizumab or atezolizumab for unresectable advanced cancer between September 2014 and December 2018. Patients were divided into the elderly (age, ≥75 years) and non-elderly (age, <75 years) groups. The detailed immune-related adverse events (irAE) profile and development of critical complications were evaluated. To assess tolerability, the proportion of patients who continued PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor for >6 months was analyzed. In the two groups, a three-element frailty score, including performance status, Charlson Comorbidity Index and neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio, was estimated, and patients were divided into the low-, intermediate- and high-frailty subgroups. Safety and tolerability were evaluated using the aforementioned items. A total of 58 patients (29.4%) were aged ≥75 years. No significant difference was found in the development of irAEs, hospitalization and treatment discontinuation due to irAEs between the two groups. However, the occurrence of unexpected critical complications was significantly higher in the elderly group (P=0.03). Among the elderly patients with high frailty, more critical complications and fatal irAE (hepatitis) were observed. In this population, 33.3% were able to continue treatment for >6 months without disease progression. The present analysis based on real world data showed similar safety and tolerability of PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors in elderly patients with advanced malignancies. However, the impact of irAE in elderly patients, especially those with frailty, was occasionally greater compared with that in younger and fit patients.

Keywords: immune-related adverse events, programmed cell death 1 inhibitors, immune checkpoint inhibitors, frail, elderly, aging

Introduction

As a result of population aging, the number of elderly patients with cancer is recently increasing, and of patients with cancer, ~70% are aged ≥65 years and 36% are aged 75 years in daily clinical practice (1). Elderly patients are frequently vulnerable and frail compared to younger patients due to comorbidities and geriatric problems, including physical or cognitive dysfunctions (2), and non-elderly patients may also have frailty with malnutrition or low performance status (PS) due to severe advanced malignancies. In these situations, conventional cancer treatments are often intolerable and have a particularly high risk of adverse events (3).

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), especially those targeting the programmed cell death-1 (PD-1) and programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1), which have improved outcomes for various advanced cancers, including non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), malignant melanoma (MM), renal cell carcinoma, urothelial cancer, head and neck cancer and gastric cancer (4–9), are generally considered to be more tolerable than conventional chemotherapy and clinical indications for immunotherapy continue to increase (4,10). These drugs may provide an opportunity for treatment of elderly or frail patients who cannot tolerate toxic chemotherapy or invasive treatment.

The age-related decline in the immune system, so called ‘immunosenescence’ has been recently reported in preclinical studies (11,12). T cells, the primary effectors of antitumor response, undergo significant changes with age. The naïve CD8+ T cells decline with age in part due to thymic involution and contraction of lymphopoietic stem cells (13), and decreased expression of CD28 on the surface of CD8+ T cells leads to decreased immune activation (14–16). While these numeric and functional defects in T cells have been characterized gradually, the potential impact of aging on efficacy and tolerability of immunotherapy in clinical practice remains unclear. Elderly patients has been underrepresented in clinical trials; moreover, those who were included had relatively good PS and function reserve capacities, which may not reflect the real-world population (17). The real-world clinical practice data in treating more vulnerable or frail patients with ICIs are severely insufficient, and identifying the safety and efficacy of ICIs in this population would be profitable.

Hence, based on a real-world cohort, we designed a two-part study: i) We evaluated the safety and tolerability of PD-1/PD-L1 monotherapy in elderly patients with advanced malignancies. ii) Using indirect markers of frailty including Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG)-PS, Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI), and neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), we estimated whether vulnerable and frail patients in the elderly and non-elderly groups were associated with higher risk of immune-related adverse events (irAEs) or complications.

Materials and methods

Patient population and data collection

We performed a retrospective review of electronic medical records of 197 patients who received nivolumab, pembrolizumab or atezolizumab as monotherapy for metastatic or unresectable advanced cancers from September 2014 to December 2018 at Kyoto Prefecture University of Medicine. These patients' data were continuously followed until the data lock on July 31, 2019. None of the patients had a history of pretreatment with other ICIs, such as ipilimumab, which is an anti-cytotoxic T-lymphocyte associated protein-4 antibody. This study was approved by the Medical Ethics Review Committee of the Kyoto Prefectural University of Medicine. Given the retrospective nature of this work, informed consent was waived for the participants included in the study in accordance with the standards of the Kyoto Prefectural University of Medicine Institutional Medical Ethics Review Committee.

All enrolled patients received PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor intravenously, according to a schedule of 3 mg/kg or 240 mg every 2 weeks for nivolumab, 2 mg/kg or 200 mg every 3 weeks for pembrolizumab, and 1,200 mg every 3 weeks for atezolizumab. The treatment was provided until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity or complication was noted.

We collected information on patients' age, sex, body mass index (BMI), tumor type, ECOG-PS (18), laboratory values, prior cancer treatments and comorbidities to calculate CCI scores at the time of induction of PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors (19). NLR, an inflammatory marker that is reported to be associated with frailty and nutritional status (20,21), and the prognostic nutritional index (PNI), which is also a nutritional marker used in various cancer types, was also calculated using laboratory findings (22–25). Additionally, we assessed the development, severity and clinical course of all irAEs, namely, thyroid dysfunction, cutaneous disorders, interstitial pneumonitis, colitis, adrenal insufficiency, hepatitis, diabetes, and encephalitis. Hepatitis was defined as liver dysfunction with compatible pathological findings from liver biopsy or determined by a hepatologist. The severity of irAE was graded according to the CTCAE 4.0 criteria.

Furthermore, the duration of PD-1/PD-L1 treatment of each patient was retrieved from the medical records. This was defined as the time from the start of PD-1/PD-L1 treatment to the date of documented disease progression or any events that led to treatment discontinuation. Evaluation of clinical responses was based on the laboratory findings and the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors version 1.1. The patients were evaluated after the first 2–3 cycles and underwent computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging every 2–3 months according to the attending physician.

Assessment

Initially, all 197 patients were divided into two groups based on their age: Elderly group (age ≥75 years) and non-elderly group (age <75 years). In the assessment of safety, development and severity of each irAE, hospitalization and discontinuation of PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor treatment due to irAEs, requirement of corticosteroids or immunosuppressants for irAEs, and development of unexpected critical complications were evaluated. Moreover, the proportion of patients who continued PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor treatment for >6 months was analyzed for verification of tolerability among the two groups.

Since no formal geriatric assessments were performed, we used indirect markers to assess frailty. Namely, we constructed a three-element frailty scoring system, including ECOG-PS, CCI and NLR. These indirect markers were evaluated at the time of first administration of PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors. PS ≥2, CCI score ≥3 and NLR ≥4 were each given one point and the frailty score (FS) was calculated by adding the points of individual factors, as shown in Table I. We defined patients with FS=0 as having low, FS=1 as intermediate and FS=2 or 3 as high frailty. Based on this score, we respectively divided the elderly and non-elderly patients into low-, intermediate-, and high-frailty subgroups and evaluated the safety and tolerability of PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor treatment as mentioned above.

Table I.

Frailty scoring system.

| Marker | Value | Score |

|---|---|---|

| Performance Status | 0-1 | 0 |

| ≥2 | 1 | |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | 0-2 | 0 |

| ≥3 | 1 | |

| Neutrophil-Lymphocyte Ratio | <4 | 0 |

| ≥4 | 1 | |

| Total | Low | 0 |

| Intermediate | 1 | |

| High | 2, 3 |

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were presented as median with range according to their distribution. Student's t-test and Mann-Whitney U test were used to compare continuous variables between the elderly and non-elderly groups. The Chi-square test or Fisher's exact test was used to compare categorical variables. A Bonferroni adjustment was used for multiple comparisons. All statistical tests were two-sided, and a P-value <0.05 indicated statistical significance. All statistical analyses were performed using JMP® 13 (SAS Institute Inc.).

Results

Baseline characteristics

This study group of 197 patients consisted of 77 patients with NSCLC, 32 with MM, 29 with head and neck cancer, 27 with renal cell carcinoma, 23 with gastric cancer, and 9 with urothelial cancer. Of these patients, 146 received nivolumab, 42 received pembrolizumab and 9 received atezolizumab. At the time of analysis, the median follow-up duration was 43 weeks (range 2–254 weeks). There were 58 patients (29.4%) aged ≥75 years and 139 patients (70.6%) aged <75 years, which constituted the elderly and non-elderly groups, respectively. The baseline clinical characteristics of the patients in the two groups are shown in Table II. The average age in the non-elderly and elderly groups was 62.5 and 79.4 years (P<0.001), respectively. There were no significant differences in sex, BMI, follow-up duration, type of PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor administered, prior therapy lines, PS, NLR and PNI. A certain deviation in tumor type was observed, and the elderly group showed fewer prior therapy lines and higher CCI scores, although these did not reach statistical significance. In addition, 2 out of 7 patients with preexisting autoimmune disease were in use of corticosteroids or immunosuppressants at baseline; namely, a 70 years old man with dermatomyositis used corticosteroids and a 79 years old woman with rheumatoid arthritis used corticosteroids and immunosuppressants.

Table II.

Baseline characteristics of non-elderly (n=139) and elderly (n=58) patients.

| Characteristics | Non-elderly (age <75 years) | Elderly (age ≥75 years) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 62.5 | 79.4 | <0.01 |

| Sex, n (male/female) | 93/46 | 39/19 | 0.96 |

| PS, n | 0.72 | ||

| 0 | 78 | 32 | |

| 1 | 45 | 17 | |

| ≥2 | 16 | 9 | |

| Median follow-up period, weeks (range) | 40 (2–254) | 52 (8–170) | 0.12 |

| Tumor type, n | 0.08 | ||

| NSCLC | 56 | 21 | |

| MM | 18 | 14 | |

| Head and neck | 25 | 4 | |

| RCC | 20 | 7 | |

| Gastric | 16 | 7 | |

| Urothelial | 4 | 5 | |

| Treatment, n | 0.84 | ||

| Nivolumab | 106 | 40 | |

| Pembrolizumab | 26 | 16 | |

| Atezolizumab | 7 | 2 | |

| Prior therapy lines, n (≤1/≥2) | 68/71 | 36/22 | 0.09 |

| CCI, n | 0.09 | ||

| 0 | 74 | 25 | |

| 1, 2 | 55 | 23 | |

| ≥3 | 10 | 10 | |

| BMI | 21.2 | 20.9 | 0.58 |

| NLR | 4.1 | 3.8 | 0.50 |

| PNI | 43.2 | 43.6 | 0.71 |

| Preexisting autoimmune disease, n | 4 | 3 | 0.43 |

PS, performance status; NSCLC, non-small cell lung carcinoma; MM, malignant melanoma; RCC, renal cell carcinoma; CCI, Charlsons comorbidity index; BMI, body mass index; NLR, neutrophil lymphocyte ratio; PNI, prognostic nutritional index.

Profiles of irAEs in the elderly and non-elderly groups

The profiles of irAEs in the elderly and non-elderly groups are shown in Table III. Moreover, 52 patients (37.4%) in the non-elderly group and 28 patients (48.3%) in the elderly group developed any irAEs of any grade, which showed a slight tendency of more irAEs in elderly patients, although the difference was not statistically significant. Moreover, the analysis of irAEs showed no significant difference in the development of cutaneous disorders, thyroid dysfunction, interstitial pneumonitis, adrenal insufficiency, hepatitis, and diabetes. The severity of irAEs and clinical outcomes related to irAEs are shown in Table IV. Grade 3–5 irAEs developed equally in the non-elderly and elderly groups [12 patients (8.6%) in the non-elderly group and 5 (8.6%) in the elderly group], although one elderly patient with renal cell carcinoma developed grade 5 hepatitis (fulminant hepatitis), which showed resistance to pulse steroid therapy and died after the 4th cycle of nivolumab. Although the following data did not show statistical significance, hospitalization due to irAEs and use of corticosteroids or immunosuppressants for irAEs were slightly higher in the elderly patients, and PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor treatment was more easily discontinued in the elderly group than in the non-elderly group [9 patients (15.5%) vs. 13 patients (9.4%) (P=0.21)]. Furthermore, unexpected critical complications developed more frequently in the elderly patients (P=0.03), including each patient with acute exacerbation of chronic heart failure, cerebral hemorrhage, femoral neck fracture due to fall and sudden unexplained death.

Table III.

Development of irAEs among the non-elderly (n=139) and elderly (n=58) groups.

| irAEs | Non-elderly (age <75 years), n (%) | Elderly (age ≥75 years), n (%) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total of irAEs | 52 (37.4) | 28 (48.3) | 0.16 |

| Thyroid dysfunction | 18 (13.1) | 12 (20.7) | 0.18 |

| Cutaneous disorders | 25 (18.0) | 12 (20.7) | 0.66 |

| Interstitial pneumonitis | 10 (7.2) | 5 (8.6) | 0.73 |

| Colitis | 6 (4.3) | 2 (3.5) | 0.78 |

| Adrenal insufficiency | 5 (3.6) | 2 (3.5) | 0.96 |

| Hepatits | 3 (2.1) | 1 (1.7) | 0.84 |

| Diabetes | 2 (1.4) | 1 (1.7) | 0.70 |

irAEs, immune related adverse events.

Table IV.

Severity of irAEs and clinical outcomes related to irAEs in the non-elderly (n=139) and elderly (n=58) patients.

| Variables | Non-elderly (age <75 years), n (%) | Elderly (age ≥75 years), n (%) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total of irAEs | 52 (37.4) | 28 (48.3) | 0.16 |

| Grade 3–5 irAEs | 12 (8.6) | 5 (8.6) | 0.99 |

| Gr3: N=9, Gr4: N=3 | Gr3: N=2, Gr4: N=2, Gr5: N=1 | ||

| Hospitalization due to irAE | 12 (8.6%) | 7 (12.1%) | 0.46 |

| Use of corticosteroids or immunosuppressants for irAE | 17 (12.2) | 8 (13.8) | 0.76 |

| Treatment discontinuation due to irAE | 13 (9.4) | 9 (15.5) | 0.21 |

| Unexpected critical complications | 1 (0.7)a | 4 (6.9)b | 0.03 |

Worsening of preexisting dermatomyositis (n=1)

Exacerbation of chornic heart failure (n=1), cerebral hemorrhage (n=1), femoral neck fracture (n=1), sudden unexplained death (n=1). irAEs, immune related adverse events; Gr, grade.

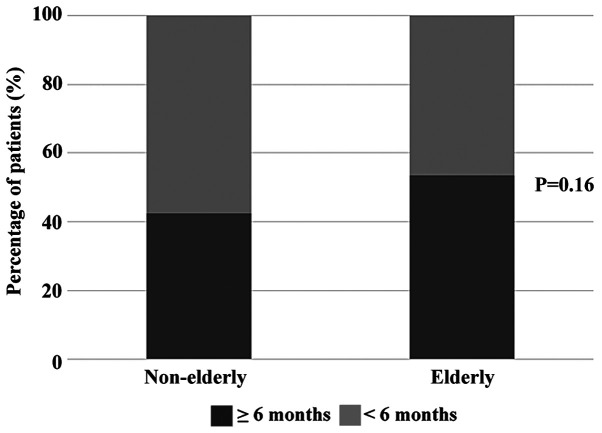

When we analyzed the treatment duration among the two groups, 59 patients (42.5%) in the non-elderly group and 31 patients (53.5%) in the elderly group were able to continue PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor treatment for >6 months (Fig. 1). In addition, patients who had longer treatment duration showed tendency to develop more irAEs in the two groups, especially in the non-elderly patients [29 patients (49.2%) with treatment period ≥6 months and 23 patients (28.8%)] with treatment period <6 months, P=0.01, data not shown). According to these results, PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors seemed to have comparable tolerability in elderly patients.

Figure 1.

Treatment period in the non-elderly and elderly groups. A total of 59 patients (42.5%) in the non-elderly group and 31 patients (53.5%) in the elderly group were able to continue programmed cell death protein-1/programmed cell death ligand 1 inhibitor treatment for >6 months. The χ2 test was performed for comparison.

Frailty scores

In the non-elderly group, 75 patients (54.0%) with FS=0, 51 patients (36.7%) with FS=1 and 13 patients (9.3%) with FS=2 or 3 were defined as patients with low, intermediate and high frailty, respectively. In the elderly group, 30 patients (51.7%) with FS=0, 16 patients (27.6%) with FS=1, and 12 patients (20.7%) with FS=2 or 3 were defined as patients with low, intermediate and high frailty, respectively. The proportion of patients with high frailty was considerably greater in the elderly group and close to significance (P=0.08).

Development of irAEs and clinical outcomes in patients with low, intermediate, and high frailty

The development of irAEs and unexpected critical complications in the three frailty subgroups of the non-elderly and elderly patients are demonstrated in Tables V and VI. In the non-elderly patients, 35 patients (46.7%) with low frailty, 15 patients (29.4%) with intermediate frailty and 2 patients (15.4%) with high frailty developed any irAEs of any grade, which showed a tendency of lower development of irAEs in patients with high frailty (P=0.09). No significant difference was shown in the development of severe irAEs among the three groups. One patient with low frailty had exacerbation of the preexisting dermatomyositis 17 days after initiation of atezolizumab.

Table V.

Development of irAEs and unexpected critical complications among the three subgroups of frailty (age <75 years).

| Variables | Low frailty (FS=0) (n=75), n (%) | Intermediate frailty (FS=1) (n=51), n (%) | High frailty (FS=2, 3) (n=13), n (%) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total of irAEs | 35 (46.7) | 15 (29.4) | 2 (15.4) | 0.09 |

| Grade 3–5 irAEs | 5 (6.7) | 5 (9.8) | 2 (15.4) | 0.55 |

| Unexpected critical complications | Worsening of preexisting dermatomyositis (n=1) | None | None |

irAEs, immune related adverse events; FS, frailty score.

Table VI.

Development of irAEs and unexpected critical complications among the three subgroups of frailty (age ≥75 years).

| Variables | Low frailty (FS=0) (n=30), n (%) | Intermediate frailty (FS=1) (n=16), n (%) | High frailty (FS=2, 3) (n=12), n (%) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total of irAEs | 17 (56.7) | 7 (43.8) | 4 (33.3) | 0.36 |

| Grade 3–5 irAEs | 2 (6.7) | 2 (12.5) | 1 (8.3) | 0.80 |

| Unexpected critical complications | Cerebral hemorrhage (n=1), femoral neck fracture (n=1) | None | Exacerbation of chornic heart failure (n=1), sudden unexplained death (n=1) |

irAEs, immune related adverse events, FS, Frailty score.

In the elderly patients, 17 patients (56.7%) with low frailty, 7 patients (43.8%) with intermediate frailty, and 4 patients (33.3%) with high frailty developed any irAEs of any grade (P=0.36). There was also no significant difference in the development of grade 3–5 irAEs among the three subgroups. However, it should be noted that two patients with high frailty developed critical complications, including a case of sudden death.

Tables VII and VIII show the clinical outcomes of all patients (12 patients in the non-elderly group, 5 in the elderly group) who developed grade 3–5 irAEs. All non-elderly patients recovered from severe irAEs, including one patient with low and one patient with intermediate frailty restarting the same PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor. In contrast, one elderly patient with high frailty died of fulminant hepatitis as mentioned above, and no other patient resumed ICI treatment afterward.

Table VII.

Clinical features of the non-elderly patients with severe irAEs.

| Case | Age, years | Sex | Tumor type | Treatment | Frailty | irAE | Grade | Remission of irAE | Restart of PD-1/PD-L1 treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 60 | M | RCC | Nivolumab | Low | Diabetes | 4 (diabetic ketoacidosis) | Yes | Yes |

| 2 | 67 | F | NSCLC | Nivolumab | Low | Diabetes | 4 (diabetic ketoacidosis) | Yes | No |

| 3 | 71 | M | Urothelial | Pembrolizumab | Low | Colitis | 3 | Yes | No |

| 4 | 68 | M | MM | Nivolumab | Low | Aderenal insufficienecy | 3 | Yes | No |

| 5 | 70 | F | NSCLC | Nivolumab | Low | Interstitial pneumonitis | 3 | Yes | No |

| 6 | 74 | F | NSCLC | Nivolumab | Intermediate | Hepatitis | 4 | Yes | No |

| 7 | 73 | M | NSCLC | Pembrolizumab | Intermediate | interstitial pneumonitis | 3 | Yes | No |

| 8 | 71 | M | NSCLC | Atezolizumab | Intermediate | Encephatitis | 3 | Yes | No |

| 9 | 63 | M | NSCLC | Nivolumab | Intermediate | Interstitial pneumonitis | 3 | Yes | No |

| 10 | 60 | M | Head and neck | Nivolumab | Intermediate | Hepatitis | 3 | Yes | Yes |

| 11 | 44 | M | Gastric | Nivolumab | High | Interstitial pneumonitis | 3 | Yes | No |

| 12 | 73 | M | NSCLC | Pembrolizumab | High | Aderenal insufficinecy | 3 | Yes | No |

irAEs, immune-related adverse events; NSCLC, non-small cell lung carcinoma; MM, malignant melanoma; RCC, renal cell carcinoma.

Table VIII.

Clinical features of the elderly patients with severe irAEs.

| Case | Age, years | Sex | Tumor type | Treatment | Frailty | irAE | Grade | Remission of irAE | Restart of PD-1/PD-L1 treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 78 | M | NSCLC | Pembrolizumab | Low | Aderenal insufficienecy | 3 | Yes | No |

| 2 | 75 | M | RCC | Nivolumab | Low | Aderenal insufficienecy | 3 | Yes | No |

| 3 | 84 | F | MM | Nivolumab | Intermediate | Cutaneous disorder | 4 (Stevens-Johnson syndrome) | Yes | No |

| 4 | 77 | F | MM | Nivolumab | Intermediate | Diabetes | 4 (diabetic ketoacidosis) | Yes | No |

| 5 | 80 | F | RCC | Nivolumab | High | Hepatitis | 5 (fulminant hepatits) | No (died) | No |

irAEs, immune-related adverse events; NSCLC, non-small cell lung carcinoma; MM, malignant melanoma; RCC, renal cell carcinoma.

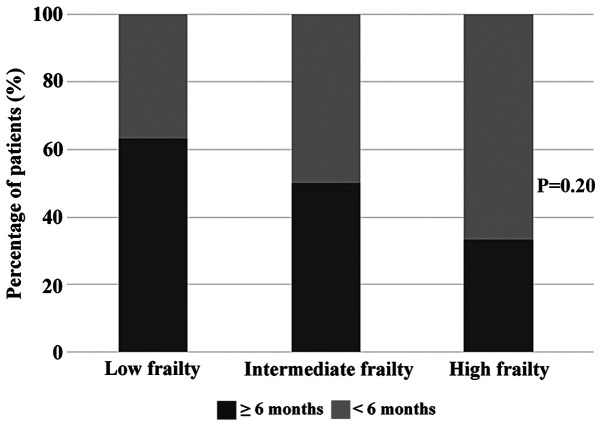

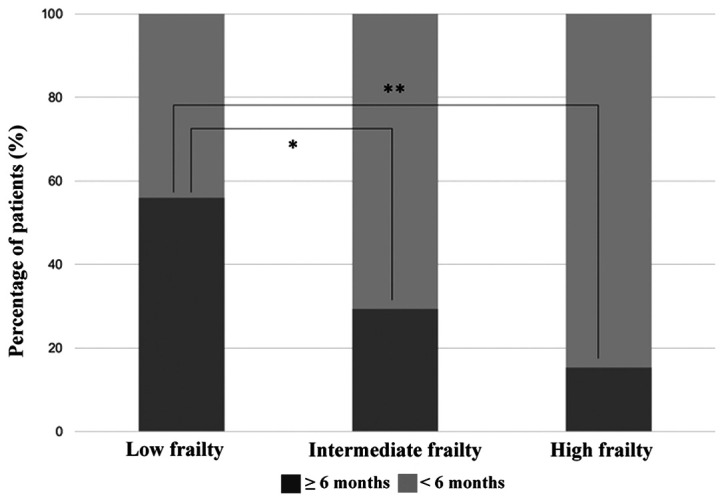

When we focused on the treatment duration of PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor among the three frailty subgroups, patients with low frailty showed a tendency to continue treatment for >6 months in both non-elderly and elderly population (Figs. 2 and 3). Nevertheless, 33.3% of patients with high frailty aged ≥75 years were able to continue PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor treatment for >6 months, suggesting a certain level of efficacy and tolerability of these drugs in this population.

Figure 2.

Treatment period in the three frailty subgroups of patients aged <75 years. A total of 42 patients (56.0%), 15 patients (29.4%) and 2 patients (15.4%) in the low-, intermediate- and high-frailty subgroups, respectively, were able to continue programmed cell death protein-1/programmed cell death ligand 1 inhibitor treatment for >6 months. The proportion was significantly greater in the low-frailty group than the other groups. Fisher's exact test was used and Bonferroni adjustment was used for multiple comparisons. *P<0.05; **P<0.01.

Figure 3.

Treatment period in the three frailty subgroups of patients aged ≥75 years. A total of 19 patients (63.3%), 8 patients (50.0%) and 4 patients (33.3%) in the low-, intermediate- and high-frailty subgroups, respectively, were able to continue programmed cell death protein-1/programmed cell death ligand 1 inhibitor treatment for >6 months. There was no significant difference among the three subgroups (P=0.20). Fisher's exact test was used and Bonferroni adjustment was used for multiple comparisons.

Discussion

In this study, we described the safety and tolerability of PD-1 inhibitors in elderly and frail patients with advanced malignancies. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate the correlation between indirect frailty markers and clinical outcomes in patients with advanced cancer treated by PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors.

Our data showed that elderly patients developed slightly more irAEs of any grade than non-elderly patients, although this was not statistically significant. In detail, no significant difference was found in the development of cutaneous disorders, thyroid dysfunction, interstitial pneumonitis, adrenal insufficiency, hepatitis, and diabetes. Moreover, the development of severe irAEs was similar between the non-elderly and elderly patients. However, hospitalization or treatment discontinuation due to irAEs and use of corticosteroids or immunosuppressants were more frequent in the elderly group. Additionally, unexpected critical complications developed more often in this group, including a case of acute exacerbation of chronic heart failure, cerebral hemorrhage and sudden death.

When we assessed frailty using indirect markers such as PS, CCI and NLR, the incidence of severe irAEs was not associated with the frailty levels in both non-elderly and elderly groups. In non-elderly patients, all recovered with proper treatment and each case with low/intermediate frailty were able to restart the same PD-1 inhibitor. On the contrary, none of the patients were able to restart PD-1 treatment, and grade 5 hepatitis and fatal complications were observed in the high-frailty subgroup. This supports the idea that assessment of frailty is especially important in elderly patients.

In previous clinical trials, no major increase in the incidence of irAEs was noted in this population (26–28). However, only relatively fit patients were enrolled and patients with reduced functional reserve or age-related comorbidities were excluded in these trials and therefore not representative of the ‘real-world’ population. In limited observational studies based on more general population of patients, contradictory results are reported. Sattar et al (29) and Leroy et al (30) showed a trend of higher incidence of irAEs in elderly patients. Muchnik et al (31) reported that a larger proportion of elderly patients were hospitalized and required corticosteroids and treatment discontinuation. Although not statistically significant, our data also showed a trend to increased irAEs of any grade with more frequent hospitalization, need of immune-modulating medication and treatment discontinuation in elderly patients. Meanwhile, our results also showed that the proportion of patients who were able to continue PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor treatment for >6 months was slightly larger in the elderly patients. This suggests that PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors may have comparable tolerability and provide similar levels of benefit to elderly patients. These ambivalent findings were found retrospectively with small sample size, although it implies further investigation of the application of ICIs in elderly patients.

Patients with advanced malignancies have an increased risk of frailty due to cancer cachexia or tumor-related disabilities, and more than half of elderly patients are vulnerable or frail (32). Selecting frail patients using geriatric assessment can help personalize treatment decisions, which leads to less treatment-related adverse events and mortality (3). However, the best geriatric assessment tool to evaluate frailty has still not reached consensus and consequently not widely used in daily clinical practice (2). ICI treatment is generally considered to be more tolerable than chemotherapy, although there are still concerns about the greater impact of irAEs in frail patients than in fit patients due to comorbidities and reduced functional reserve. From the abovementioned background, only a few studies have described the correlation between frailty and safety of immunotherapy. Welaya et al (33) did not find any relationships between impairment in geriatric assessment domains and complications but showed that patients with impairments of instrumental activities of daily living had shorter treatment duration. Archibald et al (34) used indirect frailty markers reporting that frail elderly patients had similar response rates and treatment toxicity compared to fit patients. We also used indirect markers such as ECOG-PS, CCI and NLR, which have been reported to correlate with frailty (20,35,36), and created an original scoring system showing marginally difference between elderly and non-elderly patients. Indeed, this system is not sufficient, although provided a certain indication of frailty in cancer patients. Further evaluation of frailty markers, classification systems and geriatric assessment tools are urgently warranted in this field.

In this study, we did not find a correlation between the development of grade 3–5 irAEs and frailty levels but warned that fatal irAEs and complications may develop more frequently in frail elderly patients. This may be a result of reduced functional reserve or interaction of adverse events and comorbidities. Although some recent studies have reported the safety and efficacy of retreatment with ICIs after irAEs, contradictory reports exist and no consensus has been reached yet (37–39). Therefore, restarting ICIs after irAEs may be too challenging for these patients. Regardless of age, the treatment duration was shorter in frail patients. Perhaps, this was because frailty was defined based on PS and NLR, which can be related to disease activity (40,41), and patients may have had more rapidly progressive cancer, in which PD-1 inhibitors are less effective (42). Besides, the incidence of irAEs of any grade was low in frail patients, especially in the younger group. Although, we speculate that this was influenced by the shorter treatment duration. It is noteworthy that 33.3% of elderly patients with high frailty were able to continue PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor treatment for >6 months. We consider this data valuable because these patients may have no indication of conventional chemotherapy, and PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors may provide an opportunity to prolong life expectancy with safety and mild toxicity. This data may become more meaningful when PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor treatment indication has expanded more broadly, and we hope this result serves as a basis for future research.

There are several limitations in this study. First, this was a single-center retrospective study. Therefore, the analyzed data were limited by its retrospective nature, and the patient sample size was relatively small. However, the collected data were purely based on daily clinical practice in our hospital and we did not include patients on clinical trials because these patients could have closer monitoring of adverse events; thus, we believe that our cohort was representative of the general population. Second, we used indirect markers for the evaluation of frailty instead of formal geriatric assessment, because it was not performed in our study cohort. Indeed, geriatric assessment will help us clearly identify vulnerable and frail patients. Nevertheless, our three-element frailty scoring system showed more frail patients in the elderly patients indicating that this method was reasonable.

Therefore, based on data of the ‘real-world’ population, we demonstrated that mild and severe irAEs developed similarly in non-elderly and elderly patients treated with PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors. In elderly patients, frailty evaluation seemed to be essential in the safe management of PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor treatment. Simultaneously, we also note that a certain proportion of frail elderly patients can receive great benefit from these drugs with close monitoring. Therefore, further prospective studies are required to evaluate the safety of ICI treatment in frail patients using geriatric assessment and identify predictive biomarkers for optimizing the application of antitumor immunotherapy.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- ICI

immune checkpoint inhibitors

- PD-1

programmed cell death protein-1

- PD-L1

programmed cell death ligand 1

- NSCLC

non- small cell lung cancer

- MM

malignant melanoma

- irAEs

immune-related adverse events

- CTLA-4

cytotoxic T-lymphocyte associated protein-4

- PS

performance status

- CCI

Charlson Comorbidity Index

- NLR

neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio

Funding

No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors' contributions

TS, TI and YI were responsible for the design of the study, selection and analysis and interpretation of the data. They also have revised critically the manuscript for important intellectual content. TI, JU, YT, SK, JA, AA, HT, TK, HK, FH, MI, SH, OU, TT and KT were responsible for the acquisition and clinical interpretation of the data. All authors had full access to all of the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The present study was designed under the responsibility of Kyoto Prefectural University of Medicine, in conjunction with the steering committee (approval no. ERB-C-867-1). Given the retrospective nature of this work, the requirement for informed consent was waived for the individual participants included in the study in accordance with the standards of the Kyoto Prefectural University of Medicine Institutional Medical Ethics Review Committee.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

YI has received research grants and lecture fees from Ono Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Bristol-Myers Squibb, MSD and research grants from Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. TI and TT received lecture fees from Ono Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. and Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. TT has also received research grants from Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. KT and OU have received research grants from Ono Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. and Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. KT has also received lecture fees from Ono Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Bristol-Myers Squibb, MSD and Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. The authors declare that all these conflicts of interest are not connected with the issue of this paper. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.National Cancer Institute, corp-author. Cancer Stat Facts: Cancer of Any Site. [Dec 16;2019 ]; Available from: https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/all.html. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wildiers H, Heeren P, Puts M, Topinkova E, Janssen-Heijnen ML, Extermann M, Falandry C, Artz A, Brain E, Colloca G, et al. International Society of Geriatric Oncology consensus on geriatric assessment in older patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:2595–2603. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.54.8347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hurria A, Togawa K, Mohile SG, Owusu C, Klepin HD, Gross CP, Lichtman SM, Gajra A, Bhatia S, Katheria V, et al. Predicting chemotherapy toxicity in older adults with cancer: A prospective multicenter study. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:3457–3465. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.34.7625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Robert C, Long GV, Brady B, Dutriaux C, Maio M, Mortier L, Hassel JC, Rutkowski P, McNeil C, Kalinka-Warzocha E, et al. Nivolumab in previously untreated melanoma without BRAF mutation. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:320–330. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1412082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Borghaei H, Paz-Ares L, Horn L, Spigel DR, Steins M, Ready NE, Chow LQ, Vokes EE, Felip E, Holgado E, et al. Nivolumab versus docetaxel in advanced nonsquamous non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1627–1639. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1507643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Motzer RJ, Escudier B, McDermott DF, George S, Hammers HJ, Srinivas S, Tykodi SS, Sosman JA, Procopio G, Plimack ER, et al. CheckMate 025 Investigators Nivolumab versus everolimus in advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1803–1813. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1510665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ferris RL, Blumenschein G, Jr, Fayette J, Guigay J, Colevas AD, Licitra L, Harrington K, Kasper S, Vokes EE, Even C, et al. Nivolumab for recurrent squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1856–1867. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1602252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ansell SM, Lesokhin AM, Borrello I, Halwani A, Scott EC, Gutierrez M, Schuster SJ, Millenson MM, Cattry D, Freeman GJ, et al. PD-1 blockade with nivolumab in relapsed or refractory Hodgkin's lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:311–319. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1411087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kang Y-K, Boku N, Satoh T, Ryu M-H, Chao Y, Kato K, Chung HC, Chen JS, Muro K, Kang WK, et al. Nivolumab in patients with advanced gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction cancer refractory to, or intolerant of, at least two previous chemotherapy regimens (ONO-4538-12, ATTRACTION-2): A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2017;390:2461–2471. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31827-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garon EB, Rizvi NA, Hui R, Leighl N, Balmanoukian AS, Eder JP, Patnaik A, Aggarwal C, Gubens M, Horn L, et al. KEYNOTE-001 Investigators Pembrolizumab for the treatment of non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:2018–2028. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1501824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Elias R, Morales J, Rehman Y, Khurshid H. Immune checkpoint inhibitors in older adults. Curr Oncol Rep. 2016;18:47. doi: 10.1007/s11912-016-0534-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elias R, Karantanos T, Sira E, Hartshorn KL. Immunotherapy comes of age: Immune aging & checkpoint inhibitors. J Geriatr Oncol. 2017;8:229–235. doi: 10.1016/j.jgo.2017.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tomihara K, Curiel TJ, Zhang B. Optimization of immunotherapy in elderly cancer patients. Crit Rev Oncog. 2013;18:573–583. doi: 10.1615/CritRevOncog.2013010591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Czesnikiewicz-Guzik M, Lee WW, Cui D, Hiruma Y, Lamar DL, Yang ZZ, Ouslander JG, Weyand CM, Goronzy JJ. T cell subset-specific susceptibility to aging. Clin Immunol. 2008;127:107–118. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2007.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weng NP, Akbar AN, Goronzy J. CD28(−) T cells: Their role in the age-associated decline of immune function. Trends Immunol. 2009;30:306–312. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2009.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Filaci G, Fravega M, Negrini S, Procopio F, Fenoglio D, Rizzi M, Brenci S, Contini P, Olive D, Ghio M, et al. Nonantigen specific CD8+ T suppressor lymphocytes originate from CD8+CD28− T cells and inhibit both T-cell proliferation and CTL function. Hum Immunol. 2004;65:142–156. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2003.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Loh KP, Wong ML, Maggiore R. From clinical trials to real-world practice: Immune checkpoint inhibitors in older adults. J Geriatr Oncol. 2019;10:384–388. doi: 10.1016/j.jgo.2019.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oken MM, Creech RH, Tormey DC, Horton J, Davis TE, McFadden ET, Carbone PP. Toxicity and response criteria of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. Am J Clin Oncol. 1982;5:649–655. doi: 10.1097/00000421-198212000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: Development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nishijima TF, Deal AM, Williams GR, Guerard EJ, Nyrop KA, Muss HB. Frailty and inflammatory markers in older adults with cancer. Aging (Albany NY) 2017;9:650–664. doi: 10.18632/aging.101162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sato Y, Gonda K, Harada M, Tanisaka Y, Arai S, Mashimo Y, Iwano H, Sato H, Ryozawa S, Takahashi T, et al. Increased neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio is a novel marker for nutrition, inflammation and chemotherapy outcome in patients with locally advanced and metastatic esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Biomed Rep. 2017;7:79–84. doi: 10.3892/br.2017.924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mirili C, Yılmaz A, Demirkan S, Bilici M, Basol Tekin S. Clinical significance of prognostic nutritional index (PNI) in malignant melanoma. Int J Clin Oncol. 2019;24:1301–1310. doi: 10.1007/s10147-019-01461-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang W, Ye B, Liang W, Ren Y. Preoperative prognostic nutritional index is a powerful predictor of prognosis in patients with stage III ovarian cancer. Sci Rep. 2017;7:9548. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-10328-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li D, Yuan X, Liu J, Li C, Li W. Prognostic value of prognostic nutritional index in lung cancer: A meta-analysis. J Thorac Dis. 2018;10:5298–5307. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2018.08.51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Onodera T, Goseki N, Kosaki G. Prognostic nutritional index in gastrointestinal surgery of malnourished cancer patients. Nihon Geka Gakkai Zasshi. 1984;85:1001–1005. (In Japanese) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Singh H, Kim G, Maher VE, Beaver JA, Pai-Scherf LH, Balasubramaniam S. FDA subset analysis of the safety of nivolumab in elderly patients with advanced cancers. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(Suppl 15):10010. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.34.15_suppl.10010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nosaki K, Saka H, Hosomi Y, Baas P, de Castro G, Jr, Reck M, Wu YL, Brahmer JR, Felip E, Sawada T, et al. Safety and efficacy of pembrolizumab monotherapy in elderly patients with PD-L1-positive advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: Pooled analysis from the KEYNOTE-010, KEYNOTE-024, and KEYNOTE-042 studies. Lung Cancer. 2019;135:188–195. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2019.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Spigel D, Schwartzberg L, Waterhouse D, Chandler J, Hussein M, Jotte R, Stepanski E, Mccleod M, Page R, Sen R, et al. Is nivolumab safe and effective in elderly and PS2 patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC)? Results of CheckMate 153. J Thorac Oncol. 2017;12:S1287–S1288. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2016.11.1821. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sattar J, Kartolo A, Hopman WM, Lakoff JM, Baetz T. The efficacy and toxicity of immune checkpoint inhibitors in a real-world older patient population. J Geriatr Oncol. 2019;10:411–414. doi: 10.1016/j.jgo.2018.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leroy V, Gerard E, Dutriaux C, Prey S, Gey A, Mertens C, Beylot-Barry M, Pham-Ledard A. Adverse events need for hospitalization and systemic immunosuppression in very elderly patients (over 80 years) treated with ipilimumab for metastatic melanoma. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2019;68:545–551. doi: 10.1007/s00262-019-02298-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Muchnik E, Loh KP, Strawderman M, Magnuson A, Mohile SG, Estrah V, Maggiore RJ. Immune checkpoint inhibitors in real-world treatment of older adults with non-small cell lung cancer. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67:905–912. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Handforth C, Clegg A, Young C, Simpkins S, Seymour MT, Selby PJ, Young J. The prevalence and outcomes of frailty in older cancer patients: A systematic review. Ann Oncol. 2015;26:1091–1101. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Welaya K, Loh KP, Messing S, Szuba E, Magnuson A, Mohile SG, Maggiore RJ. Geriatric assessment and treatment outcomes in older adults with cancer receiving immune checkpoint inhibitors. J Geriatr Oncol. 2020;11:523–528. doi: 10.1016/j.jgo.2019.05.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Archibald WJ, Victor AI, Strawderman MS, Maggiore RJ. Immune checkpoint inhibitors in older adults with melanoma or cutaneous malignancies: The Wilmot Cancer Institute experience. J Geriatr Oncol. 2020;11:496–502. doi: 10.1016/j.jgo.2019.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gleason LJ, Benton EA, Alvarez-Nebreda ML, Weaver MJ, Harris MB, Javedan H. FRAIL questionnaire screening tool and short-term outcomes in geriatric fracture patients. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2017;18:1082–1086. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2017.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Facon T, Dimopoulos MA, Meuleman N, Belch A, Mohty M, Chen WM, Kim K, Zamagni E, Rodriguez-Otero P, Renwick W, et al. A simplified frailty scale predicts outcomes in transplant-ineligible patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma treated in the FIRST (MM-020) trial. Leukemia. 2020;34:224–233. doi: 10.1038/s41375-019-0539-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Santini FC, Rizvi H, Plodkowski AJ, Ni A, Lacouture ME, Gambarin-Gelwan M, Wilkins O, Panora E, Halpenny DF, Long NM, et al. Safety and efficacy of re-treating with immunotherapy after immune-related adverse events in patients with NSCLC. Cancer Immunol Res. 2018;6:1093–1099. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-17-0755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Simonaggio A, Michot JM, Voisin AL, Le Pavec J, Collins M, Lallart A, Cengizalp G, Vozy A, Laparra A, Varga A, et al. Evaluation of readministration of immune checkpoint inhibitors after immune-related adverse events in patients with cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2019;5:1310. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.1022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dolladille C, Ederhy S, Sassier M, Cautela J, Thuny F, Cohen AA, Fedrizzi S, Chrétien B, Da-Silva A, Plane AF, et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitor rechallenge after immune-related adverse events in patients with cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2020;6:865. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.0726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bowen RC, Little NAB, Harmer JR, Ma J, Mirabelli LG, Roller KD, Breivik AM, Signor E, Miller AB, Khong HT. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio as prognostic indicator in gastrointestinal cancers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Oncotarget. 2017;8:32171–32189. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.16291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Templeton AJ, McNamara MG, Šeruga B, Vera-Badillo FE, Aneja P, Ocaña A, Leibowitz-Amit R, Sonpavde G, Knox JJ, Tran B, et al. Prognostic role of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in solid tumors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106:dju124. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dju124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kato K, Masuishi T, Fushiki K, Nakano S, Kawakami T, Kawamoto Y, Narita Y, Tsushima T, Nakatsumi H, Kadowaki S, et al. Impact of tumor growth rate during preceding treatment on tumor response to nivolumab or irinotecan in advanced gastric cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(Suppl 4):84. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2019.37.4_suppl.84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.