Abstract

Background

Wearable trackers are an increasingly popular tool among healthy adults and are used to facilitate self-monitoring of physical activity.

Objective

We aimed to systematically review the effectiveness of wearable trackers for improving physical activity and weight reduction among healthy adults.

Methods

This review used the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) methodology and reporting criteria. English-language randomized controlled trials with more than 20 participants from MEDLINE, CINAHL, Cochrane Library, Web of Science, PubMed, and Scopus (2000-2017) were identified. Studies were eligible for inclusion if they reported an intervention group using wearable trackers, reporting steps per day, total moderate-to-vigorous physical activity, activity, physical activity, energy expenditure, and weight reduction.

Results

Twelve eligible studies with a total of 1693 participants met the inclusion criteria. The weighted average age was 40.7 years (95% CI 31.1-50.3), with 64.4% women. The mean intervention duration was 21.4 weeks (95% CI 6.1-36.7). The usage of wearable trackers was associated with increased physical activity (standardized mean difference 0.449, 95% CI 0.10-0.80; P=.01). In the subgroup analyses, however, wearable trackers demonstrated no clear benefit for physical activity or weight reduction.

Conclusions

These data suggest that the use of wearable trackers in healthy adults may be associated with modest short-term increases in physical activity. Further data are required to determine if a sustained benefit is associated with wearable tracker usage.

Keywords: wearable activity tracker, physical activity, healthy adults, randomized controlled trials

Introduction

Wearable activity trackers have rapidly emerged in the past decade as consumer devices to support self-monitoring of physical activity [1,2]. The use of these devices has increased exponentially, and the global sales of wearables in health care are expected to reach US $4.4 billion in 2019 and US $4.5 billion by 2020 [3].

In the past, structured lifestyle interventions have utilized education with behavior change techniques, provision of written information materials, and telephone counseling in a series of combination and permutation [4,5]. These interventions are successful in the short term but not in the long term, and they tend to be labor-intensive and costly [2,6,7]. Today, the availability and accessibility of wearable trackers equip consumers with the ability to monitor their physical activity along with online applications with motivational and tracking tools. Several systematic reviews have shown that wearable trackers are effective [4,6,8].

Contemporary wearable trackers differ from conventional pedometers as they are sophisticated devices providing real-time multidimensional feedback on physiological and health parameters including steps, calories burned, distance covered, active time, sleep assessment, and heart rate, and may include mobile connectivity or an internet application to provide personalized feedback reports [9].

To date, most of the literature on wearable trackers has focused on their feasibility, validity, and reliability [10] with limited data on the impact using these devices has on improving physical activity [6,11]. The primary purpose of this study is to evaluate the effectiveness of wearable trackers and their impact on physical activity levels in healthy adult populations with secondary outcomes of weight change in overweight populations.

Methods

Protocol and Registration

The protocol for this study is registered under PROSPERO with registration number CRD42019131868.

Eligibility Criteria, Information Sources, Search and Study Selection

PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) [12] methods and reporting were used to perform a systematic literature search with a professional medical librarian (Multimedia Appendix 1) on English-language randomized controlled trials published between January 1, 2000, and August 1, 2017.

We considered English-language studies eligible for inclusion if they reported an intervention with at least one of the groups using wearable trackers to provide objective feedback on physical activity to the wearer, alone or in combination with other interventions to enhance physical activity. Only randomized controlled trials with more than 20 participants in the adult outpatient and community setting that reported a change in physical activity behavior (total steps, total activity, the proportion of participants at activity goal) were included. We are looking at the healthy population and therefore excluded studies that required participants to be hospitalized or confined to a research center, studies in disease populations, and obese populations. We excluded studies that were predominantly pedometer-based interventions since we were only considering the effect of wearable trackers.

Data Collection Process and Data Items

Two authors independently abstracted three categories of variables from each of the included studies, with differences resolved by consensus: intervention variables (intervention duration); participant variables; quality variables (method of blinding control participants to step counts, the use of validity- and reliability-tested wearable trackers, the extent of affordability of wearable trackers and the extent to which co-interventions may have affected physical activity). If the study reported results from a different period, we used the final immediate post-intervention data in our primary analysis. For studies that reported different intensities of physical activity instead of steps per day, we chose the walking intensity results for the primary analysis.

Risk of Bias and Quality Assessment

The risk of bias was assessed using the Cochrane risk of bias tool [13] across seven domains. Each domain was scored with low (L), unclear (U), or high (H) risk of bias. The domains assessed were as follows:

Random sequence generation: Was there selective bias (biased allocation to interventions) due to inadequate generation of a randomized sequence?

Allocation concealment: Was there selective bias (biased allocation to interventions) due to inadequate concealment of allocations prior to assignment?

Selective outcome reporting: Was there reporting bias due to selective outcome reporting?

Blinding outcome assessment: Was there detection bias due to knowledge of the allocated interventions by outcome assessors?

Blinding participants and personnel: Was there performance bias due to knowledge of the allocated interventions by participants and personnel during the study?

Incomplete outcome data: Was there attribution bias due to knowledge of the allocated interventions by outcome assessors?

Other sources of bias: Was there bias due to problems not covered elsewhere?

The GRADE (Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation) system was used to rank the quality of evidence for each study [14]. The GRADE approach uses five considerations (study limitations, consistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness, and publication bias). The criteria for the grade of evidence are as follows:

High: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimated effect.

Moderate: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely close to the estimated effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different

Low: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimated effect.

Very low quality: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of the effect.

Synthesis of Results

Statistical analysis was performed with Comprehensive Meta-Analysis Version 3 [15]. For each of the included studies, we calculated the effect sizes of physical activity for our primary interest outcome using steps/day, total moderate-vigorous physical activity (MVPA), activity units or physical activity energy expenditure, depending on the available results from the studies with steps/day taking priority. We calculated the summary outcomes or the standardized mean difference (SMD) (95% CI) using random-effects calculations. SMD is used since the included studies all assess the same outcome, physical activity, but they measure it in a variety of ways (steps/day, MVPA, energy expenditure). Hence, differences in means that are the same proportion of the standard deviation will have the same SMD, regardless of the actual scales used to make the measurements [16].

The I2 statistic was used as a measure of variability in observed effects estimates attributable to between-study heterogeneity [17]. For variables exhibiting mild heterogeneity (I2≤25%), pooled estimates were derived with fixed effects models. For variables exhibiting more than moderate heterogeneity (I2>25%), pooled estimates were derived with random-effects models. Sub-group analysis was used to assess secondary outcomes.

Results

Study Selection

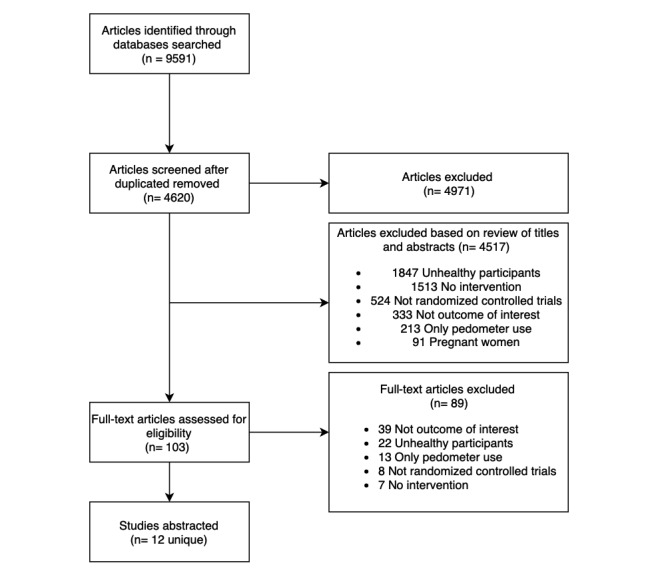

The primary search identified a total of 9591 studies from MEDLINE (n=1910), CINAHL (n=62), Cochrane Library (n=2871), Web of Science (n=1633), PubMed (n=1280), and Scopus (n=1835), as detailed in Multimedia Appendix 1. There were 4620 unique citations in which 103 full texts were retrieved for further review after applying the Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome, and Study type [18] criteria of inclusion and exclusion studies (Multimedia Appendix 2) at the title-and-abstract screening level. A total of 12 unique papers were retained for data abstraction (Figure 1) [19].

Figure 1.

PRISMA Flow Chart.

Study Characteristics

Characteristics of the included studies are presented in Table 1, and the intervention and comparators are presented in Table 2. A total of 1693 participants were included from 12 randomized trials. Included studies were published from 2007 to 2017.

Table 1.

Characteristics of participants in the included studies.

| Study name, publication year | Sample size | Participant characteristics | Study duration (weeks) | ||

|

|

|

Health status | Mean age (years) | Proportion |

|

| Ashe, 2016 [20] | 25 | Healthy participants | 40.1 | Women: 100% | 26 |

| Buis, 2017 [21] | 40 | Healthy overweight adults | 61.5 | Women: 66%; white ethnicity: 66% | 12 |

| Cadmus-Bertram, 2015 [22] | 51 | Healthy and overweight participants | 60.0 | White ethnicity: 92% | 16 |

| Godino, 2013 [23] | 466 | Healthy participants | 47.7 | Women: 46%; white ethnicity: 96% | 8 |

| Hurling, 2007 [24] | 77 | Healthy participants | 40.3 | Women: 66%; white ethnicity: 99% | 9 |

| Jakicic, 2016 [25] | 471 | Healthy overweight adults | 30.9 | Women: 71%; white ethnicity: 77% | 104 |

| Martin, 2015 [26] | 49 | Healthy overweight adults | 58.0 | Women: 46%; white ethnicity: 79% | 5 |

| Melton, 2016 [27] | 69 | Healthy participants | 19.7 | Women: 100%; black ethnicity: 100% | 6 |

| Poirier, 2007 [28] | 264 | Healthy participants | 39.9 | Women: 66%; white ethnicity: 77% | 7 |

| Shrestha, 2013 [29] | 28 | Healthy overweight adults | 32.1 | Women: 54% | 26 |

| Thompson, 2014 [30] | 49 | Healthy participants | 79.1 | Women: 91%; white ethnicity: 66% | 26 |

| Thorndike, 2014 [31] | 104 | Healthy participants | 29.0 | Women: 54% | 12 |

Table 2.

Characteristics of intervention and comparators of included studies.

| Study Name, Year | Intervention Device | Intervention | Comparator |

| Ashe, 2016 [20] | Fitbit | 26 weeks of group-based education, social support, individualized physical activity prescription, given Fitbit | 26 weeks: only received health-related information |

| Buis, 2017 [21] | Jawbone Up24 | Received a Jawbone Up24 monitor, a tablet with Jawbone Up app installed, and brief weekly telephone counseling | Waitlist control (did not receive any intervention until after their final assessment where they were provided the intervention in full) |

| Cadmus-Bertram, 2015 [22] | Fitbit | 16 weeks of Web-Based Tracking Group: Fitbit, instructional session, follow-up call at the fourth week | 16 weeks of standard pedometer |

| Godino, 2013 [23] | Combined HR monitor and accelerometer (Actiheart) | 8 weeks of wearing of Actiheart with one of three different types of feedback (simple, visual, contextualized) | 8 weeks of wearing of Actiheart but with no feedback until the end of the trial |

| Hurling, 2007 [24] | Wrist-worn accelerometer | 9 weeks of wristworn accelerometer, weekly exercise schedule, email reminders, real-time feedback via the internet | 9 weeks of wrist-worn accelerometer with no feedback |

| Jakicic, 2016 [25] | FIT Core; BodyMedia | 24 weeks of enhanced intervention: wearable technology, accompanying web interface to monitor diet and physical activity | 24 weeks of standard intervention: website for self-monitoring of diet and physical activity |

| Martin, 2015 [26] | Fitbug Orb | 3-arm study

|

Blinded participants with no feedback |

| Melton, 2016 [27] | Jawbone UP | 6 weeks of wearing Jawbone UP band and engaging with the application daily with weekly reminders | 6 weeks of using MyFitnessPal application |

| Poirier, 2007 [28] | Variety of activity trackers | 2-arm study

|

2-arm study

|

| Shrestha, 2013 [29] | Polar FA20 accelerometer | 1 time 1.5-hour lifestyle instruction and 26 weeks of continuous accelerometer use and feedback | 26 weeks of self-directed exercise and/or US Army mandated physical training |

| Thompson, 2014 [30] | Fitbit | 26 weeks of accelerometer use and feedback, weekly brief telephone counseling sessions focused on accelerometer feedback, 6 in-person brief counseling sessions | 26 weeks of accelerometer without feedback |

| Thorndike, 2014 [31] | Fitbit e3 | 2-arm study

|

2-arm study

|

aRCT: randomized controlled trial.

Study sample sizes varied from 21 to 471 participants. The participants’ weighted average age was 40.7 years (95% CI 31.1-50.3), and 64.4% of the participants were women. The duration of interventions ranged from 6 to 104 weeks, with a mean intervention duration of 21.4 weeks (95% CI 6.1-36.7).

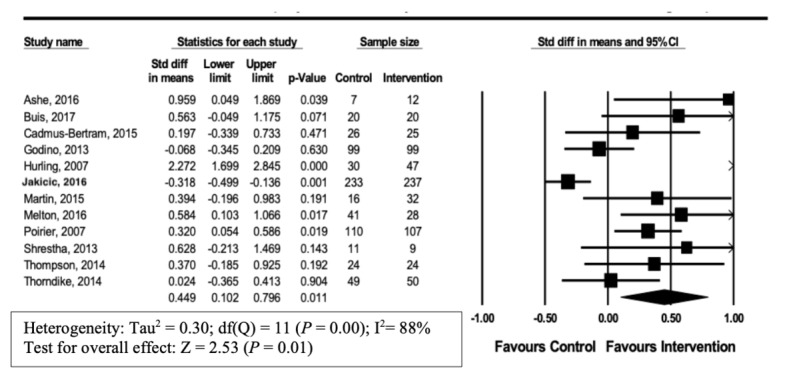

Impact of Wearable Tracker Use and Physical Activity

The primary outcome for this review was the impact of Wearable Tracker Use and Physical Activity. The overall summary estimate from 12 studies [20-31] showed a modest increase in physical activity with the usage of wearable trackers (SMD 0.449, 95% CI 0.10-0.80; P=.01). There was significant heterogeneity (I2=88%) (Figure 2). Subgroup analyses were performed for studies using steps/day or weight as reported endpoints, and in healthy versus overweight populations to explore mechanisms of heterogeneity.

Figure 2.

Forest plot of standardized mean difference (95% CI) in the effect of wearable trackers on physical activity.

We performed subgroup analyses and assessed heterogeneity to evaluate the robustness of our results [32].

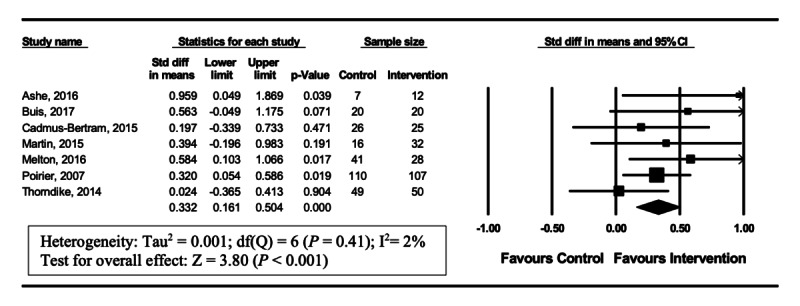

Impact of Wearable Tracker Use in Studies With Steps/Day as Primary Outcome Variable

A total of 7 [20-22,26-28,31] of 12 studies utilized steps/day as the primary endpoint. In these studies, steps/day were significantly increased by the end intervention (SMD 0.332, 95% CI 0.16-0.50; P<.001). Heterogeneity in this analysis was low (I2=2%) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Forest plot of standardized mean difference (95% Cl) in the effect of wearable trackers on steps/day.

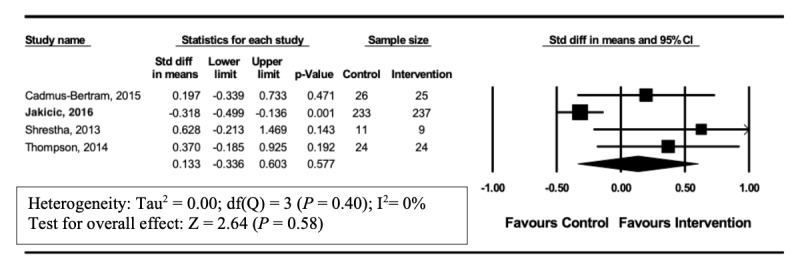

Impact of Wearable Tracker Use in Studies With Weight Loss as an Outcome

A total of 4 [22,25,29,30] of 12 studies reported weight change. However, no significant effect on weight change was observed (SMD 0.133, 95% CI –0.34 to 0.60, P=.58). Heterogeneity in this analysis was low (I2=0%) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Forest plot of standardized mean difference (95% Cl) in the effect of wearable trackers on weight loss for intervention and control group.

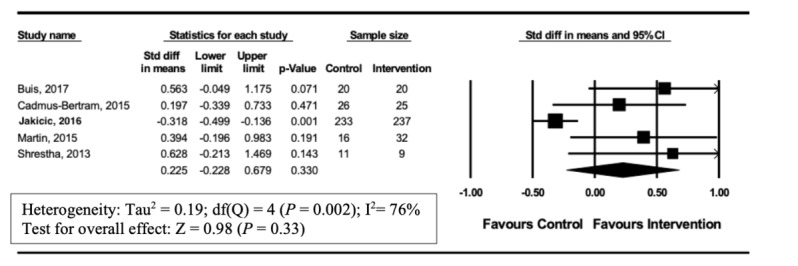

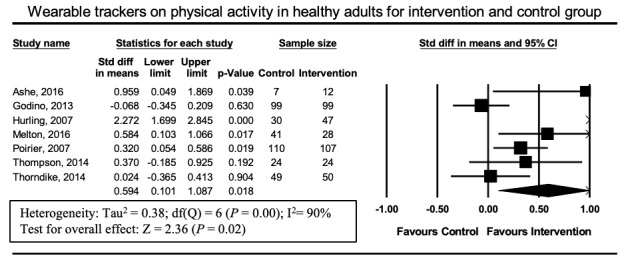

Impact of Wearable Tracker Use in Studies on Overweight Reduction

A total of 5 [21,22,25,26,29] of 12 studies reported physical activity outcomes in overweight adults. In these studies, no significant increase in physical activity occurred (SMD 0.225, 95% CI –0.23 to 0.68, P=.33). Heterogeneity in this analysis was high (I2=76%) (Figure 5). Seven [20,23,24,27,28,30,31] out of 12 studies reported physical activity outcomes in healthy adults unselected by weight. In these studies, a significant increase in physical activity was observed (SMD 0.594, 95% CI 0.10-1.09; P=.02) Heterogeneity in this analysis was high (I2=90%; Figure 6).

Figure 5.

Forest plot of standardized mean difference (95% CI) in the effect of wearable trackers on physical activity in overweight adults.

Figure 6.

Forest plot of standardized mean difference (95% CI) in the effect of wearable trackers on healthy adults.

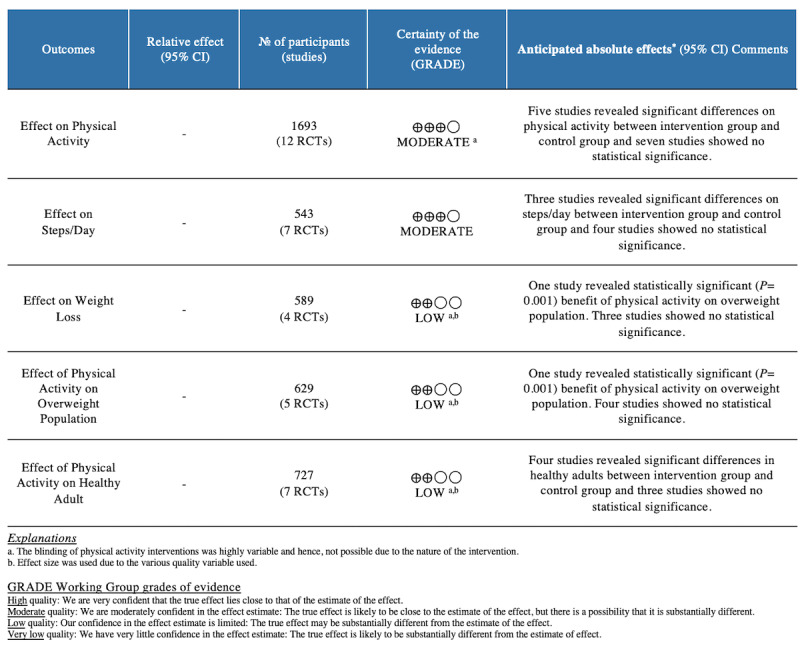

Synthesis of Results

A GRADE summary of results is presented in Figure 7. We assessed outcomes using the Cochrane GRADE approach. Results were downgraded when there was serious risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision, upgrading of a large effect size, or a dose-response gradient, all of which are possible confounding effects. Such confounding effects may create the appearance of an effect when there is none or reduce the appearance of an effect [33]. A GRADE Summary of Evidence table is provided in Multimedia Appendix 4.

Figure 7.

GRADE Working Group grades of evidence summary.

Risk of Bias Across Results

Risk of bias (ROB) is measured using the Cochrane risk of bias tool [13] for randomized controlled trials, and the summary of the evaluation is shown in Table 3. Selection bias was low as randomization was considered high in all of the studies. In 2/12 studies [20,28], methods for allocation concealment were described in insufficient details resulting in high ROB, and one [21] of the studies showed an unclear ROB. For the outcome of physical activity, the blinding of participants and personnel was highly variable as there are challenges to blinding physical activity interventions.

Table 3.

Risk of bias (Cochrane Critical Appraisal Skills Program Toola).

|

|

Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q6 | Q7 | Total score/7 | Quality Score, % |

| Ashe, 2016 [20] | Lb | L | Hc | Ud | H | L | L | 4.5 | 64 |

| Buis, 2017 [21] | L | L | U | U | U | L | L | 5.5 | 79 |

| Cadmus-Bertram, 2015 [22] | L | L | L | U | U | U | H | 4.5 | 64 |

| Godino, 2013 [23] | L | L | L | U | L | L | L | 6.5 | 93 |

| Hurling, 2007 [24] | L | L | L | U | H | L | L | 5.5 | 79 |

| Jakicic, 2016 [25] | L | L | L | U | L | L | L | 6.5 | 93 |

| Martin, 2015 [26] | L | L | L | U | H | L | L | 5.5 | 79 |

| Melton, 2016 [27] | L | L | L | L | U | L | L | 6.5 | 93 |

| Poirier, 2007 [28] | L | L | H | U | L | L | L | 5.5 | 79 |

| Shrestha, 2013 [29] | L | H | L | L | L | L | L | 6 | 86 |

| Thorndike, 2014 [31] | L | U | L | L | H | U | L | 5 | 71 |

| Thompson, 2014 [30] | L | H | L | U | L | L | L | 6 | 86 |

| Category Score (%) | 100 | 88 | 79 | 45 | 54 | 88 | 100 |

|

|

aCochrane risk of bias tool. Q1: Were there selection bias (biased allocation to interventions) due to inadequate generation of a randomized sequence? Q2: Were there selective bias (biased allocation to interventions) due to inadequate concealment of allocations prior to assignment? Q3: Were there reporting bias due to selective outcome report? Q4: Were there bias due to problems not covered elsewhere in the table? Q5: Were there performance bias due to knowledge of the allocated interventions by participants and personnel during the study? Q6: Were there detection bias due to knowledge of the allocated interventions by outcome assessors? Q7: Were there attribution bias due to amount, nature, or handling or incomplete outcome data?

bL: low risk.

cH: high risk.

dU: unclear risk.

Most of the trials (9/12, 58%) [20-25,27,28,30] did not provide sufficient methodological detail to judge bias not covered within other domains mentioned and were given judged to have an unclear ROB. The remaining studies (25%) provided sufficient details and judged to be low ROB [26,29,31].

Reporting bias was judged to be at low ROB because most of the trials (9/12, 75%) [21-26,29-31] reported details of the measured outcomes that were sufficient.

Detection bias was judged to be low since most of the trials (10/12, 83%) [20-30] provided sufficient information regarding outcome blinding assessment, and the remaining trials (16%) provided insufficient information.

Attrition bias was assessed to be low since all the trials reported the numbers reported to each group. The majority of trials (11/12, 92%) [20,21,23-31] included information on attrition and excisions from the analysis. One trial [22] did not disclose the reason for attrition/exclusion in sufficient detail, resulting in a judgment of high ROB.

Of the 12 studies measuring physical activity as an outcome, only 2 were judged to be of high ROB in terms of performance bias due to lack of blinding, and 1 study showed inadequate information regarding blinding.

Overall ROB was assessed, and the majority of studies (9/12, 75%) [21,23-30] were judged to be at low ROB and the remaining studies [20,22,31] were judged at unclear ROB.

Publication bias was determined by visual inspection of funnel plots comparing physical activity against effect size. There was visual evidence of publication bias with at least two studies falling outside the range of expected precision for their effect size (Multimedia Appendix 3).

Discussion

This meta-analysis examined the effects of wearable trackers on physical activity and is based on 12 randomized controlled trials involving 1693 participants. Overall, wearable tracker usage was associated with improvements in physical activity (SMD 0.594, 95% CI 0.10-1.09; P=.018). Interventions that included a consumer-based wearable tracker demonstrated an improvement in physical activity as compared to control groups, especially with daily steps. No clear evidence of benefit was seen from wearable tracker use in the endpoints of weight reduction or physical activity of overweight populations. Indeed, a recent review showed a potential increase in physical activity but no evidence for its effectiveness in weight loss [34].

Public Health Implications

This data may have both individual and public health implications. Wearable trackers can support continuous health monitoring at both the individual and the population level. Wearable trackers are activity monitoring tools that help to engage patients as advocates in their personalized care and have been proposed to encourage healthy behavior. Benefits are thought to include prevention or reduction of health problems, support of chronic disease self-management, enhanced provider knowledge, reduced number of healthcare visits, and personalized, localized, and on-demand interventions in ways not previously possible [35]. The low cost of delivery and the feasibility of wearable trackers makes them an attractive potential tool to facilitate self-monitoring of physical activity. The data presented in this meta-analysis demonstrates that wearable tracker usage was associated with short-term gains in physical activity [36].

A wide range of wearable trackers was used. Four [20,22,30,31] of 12 studies used Fitbit, two [21,27] used Jawbone Up, and the remaining studies used a variety of other wearable trackers. The relative proportion of commercial wearable trackers in the included studies is similar to global market shares, with Fitbit having the largest market share (20%) and hence applicable to the real world [37]. The Fitbit and Jawbone Up used in this meta-analysis have the same selected measures of “steps, distance, calories, and sleep” and are worn on the wrist [21,22,27,30,31]. A systematic review assessing the validity and reliability of Fitbit and Jawbone found that the validity and inter-device reliability of steps counts was generally high [10].

Study Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, most studies included in this meta-analysis included small study sizes with short intervention durations and limited follow-up, highlighting the necessity for longer-term studies. The variety of study designs may have been reflected by the statistical heterogeneity of the outcomes. Hence, it might be challenging to generalize the results due to heterogeneity. Future research should explore the long-term effectiveness of wearable trackers in increasing physical activity. Second, statistical estimates of publication bias identified individual, small studies with relatively large effect sizes, which may be a reflection of a file drawer effect. Third, it is difficult to establish the independent contribution of adjunctive interventions (eg, behavioral counseling, interactive health coach, weekly reminders, and text messages) that were often offered alongside wearable tracker usage. The last study was obtained in 2017, since which time there have been changes in market share due to the volatile nature of the industry. The entrance of new brands like Apple, Xiaomi, and Samsung means that an updated review is needed. Next, the skewed demographics to white females would mean that the translation to other demographics might be limited. Lastly, we restricted our search to only full-text published articles in the English language and, thus, may have excluded relevant studies outside our current scope.

Recommendations for Further Research

The current study examined the utility of wearable activity trackers in healthy adults and found a modest but measurable benefit in the population studied. Important questions for future research could include the identification of appropriate deployment strategies for these novel technologies in cardiac rehabilitation, aged care, and youth. A related question that we could not address was the role of social engagement in modulating the response of participants to wearable tracking devices.

Recommendations for Clinical Practice

The current study provides qualified support for the use of wearable activity trackers in healthy populations, showing evidence of short-term gains in physical activity, but not weight. As technology advances and these devices improve over time, future studies will be necessary to delineate the optimal use case for these devices.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this meta-analysis demonstrates the efficacy of wearable trackers in facilitating short-term increases in consumer physical activity. Future studies will be required to determine the durability of the influence of wearable tracker use on consumer physical activity behavior.

Acknowledgments

AG is supported by a Future Leader Fellowship of the National Heart Foundation of Australia (111086) and Prof Robyn A Clark Heart Foundation Future Leader Fellowship (APP ID. 100847).

Abbreviations

- GRADE

Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation

- MVPA

moderate-vigorous physical activity

- RCT

randomized controlled trial

- ROB

risk of bias

- SMD

standardized mean difference

Search strategies.

PICOS criteria for inclusion and exclusion of studies.

Funnel plot showing publication bias.

GRADE Summary of Evidence Table.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Kirk MA, Amiri M, Pirbaglou M, Ritvo P. Wearable Technology and Physical Activity Behavior Change in Adults With Chronic Cardiometabolic Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Am J Health Promot. 2018 Dec 26;33(5):778–791. doi: 10.1177/0890117118816278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van der Bij Akke K, Laurant Miranda G H, Wensing Michel. Effectiveness of physical activity interventions for older adults: a review. Am J Prev Med. 2002 Feb;22(2):120–33. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(01)00413-5.S0749379701004135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dias D, Paulo Silva Cunha J. Wearable Health Devices-Vital Sign Monitoring, Systems and Technologies. Sensors (Basel) 2018 Jul 25;18(8) doi: 10.3390/s18082414. https://www.mdpi.com/resolver?pii=s18082414 .s18082414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Howlett NT, Trivedi Daksha, Troop Nicholas A, Chater Angel Marie. Are physical activity interventions for healthy inactive adults effective in promoting behavior change and maintenance, and which behavior change techniques are effective? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Transl Behav Med. 2019 Jan 01;9(1):147–157. doi: 10.1093/tbm/iby010. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/29506209 .4913688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cradock KA, ÓLaighin Gearóid, Finucane FM, Gainforth HL, Quinlan LR, Ginis KAM. Behaviour change techniques targeting both diet and physical activity in type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2017 Feb 08;14(1):18. doi: 10.1186/s12966-016-0436-0. https://ijbnpa.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12966-016-0436-0 .10.1186/s12966-016-0436-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coughlin SS, Stewart J. Use of Consumer Wearable Devices to Promote Physical Activity: A Review of Health Intervention Studies. J Environ Health Sci. 2016 Nov;2(6) doi: 10.15436/2378-6841.16.1123. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/28428979 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hillsdon MF, Foster C, Thorogood M. Interventions for promoting physical activity. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005 Jan 25;(1):CD003180. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003180.pub2. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/15674903 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brickwood K, Watson G, O'Brien J, Williams AD. Consumer-Based Wearable Activity Trackers Increase Physical Activity Participation: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2019 Apr 12;7(4):e11819. doi: 10.2196/11819. https://mhealth.jmir.org/2019/4/e11819/ v7i4e11819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hickey AM, Freedson PS. Utility of Consumer Physical Activity Trackers as an Intervention Tool in Cardiovascular Disease Prevention and Treatment. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2016;58(6):613–9. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2016.02.006.S0033-0620(16)30016-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Evenson KR, Goto MM, Furberg RD. Systematic review of the validity and reliability of consumer-wearable activity trackers. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2015 Dec 18;12(1):159. doi: 10.1186/s12966-015-0314-1. https://ijbnpa.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12966-015-0314-1 .10.1186/s12966-015-0314-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ridgers ND, McNarry MA, Mackintosh KA. Feasibility and Effectiveness of Using Wearable Activity Trackers in Youth: A Systematic Review. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2016 Nov 23;4(4):e129. doi: 10.2196/mhealth.6540. https://mhealth.jmir.org/2016/4/e129/ v4i4e129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liberati A, Altman Douglas G, Tetzlaff Jennifer, Mulrow Cynthia, Gøtzsche Peter C, Ioannidis John P A, Clarke Mike, Devereaux P J, Kleijnen Jos, Moher David. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2009 Jul 21;339(4):b2700. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2700. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/19622552 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Gøtzsche Peter C, Jüni Peter, Moher D, Oxman AD, Savovic J, Schulz KF, Weeks L, Sterne JAC, Cochrane Bias Methods Group. Cochrane Statistical Methods Group The Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011 Oct 18;343(oct18 2):d5928–d5928. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d5928. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/22008217 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Atkins David, Best Dana, Briss Peter A, Eccles Martin, Falck-Ytter Yngve, Flottorp Signe, Guyatt Gordon H, Harbour Robin T, Haugh Margaret C, Henry David, Hill Suzanne, Jaeschke Roman, Leng Gillian, Liberati Alessandro, Magrini Nicola, Mason James, Middleton Philippa, Mrukowicz Jacek, O'Connell Dianne, Oxman Andrew D, Phillips Bob, Schünemann Holger J, Edejer Tessa Tan-Torres, Varonen Helena, Vist Gunn E, Williams John W, Zaza Stephanie, GRADE Working Group Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2004 Jun 19;328(7454):1490. doi: 10.1136/bmj.328.7454.1490. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/15205295 .328/7454/1490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Borenstein M, Hedges L, Higgins J, Rothstein H. Comprehensive Meta-Analysis Version 3. Comprehensive Meta-Analysis Version 3. [2017-07-13]. https://www.meta-analysis.com/downloads/Meta-Analysis%20Manual%20V3.pdf .

- 16.Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 The Cochrane Collaboration. United States: John Wiley & Sons Ltd; 2011. Cochrane Handbook. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Higgins JPT, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002 Jun 15;21(11):1539–58. doi: 10.1002/sim.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Methley AM, Campbell S, Chew-Graham C, McNally R, Cheraghi-Sohi S. PICO, PICOS and SPIDER: a comparison study of specificity and sensitivity in three search tools for qualitative systematic reviews. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014 Nov 21;14(1) doi: 10.1186/s12913-014-0579-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moher David, Liberati Alessandro, Tetzlaff Jennifer, Altman Douglas G, PRISMA Group Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009 Jul 21;6(7):e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. http://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ashe MC, Winters M, Hoppmann CA, Dawes MG, Gardiner PA, Giangregorio LM, Madden KM, McAllister MM, Wong G, Puyat JH, Singer J, Sims-Gould J, McKay HA. "Not just another walking program": Everyday Activity Supports You (EASY) model-a randomized pilot study for a parallel randomized controlled trial. Pilot Feasibility Stud. 2015 Jan 12;1(1):4. doi: 10.1186/2055-5784-1-4. https://pilotfeasibilitystudies.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/2055-5784-1-4 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lyons EJ, Swartz MC, Lewis ZH, Martinez E, Jennings K. Feasibility and Acceptability of a Wearable Technology Physical Activity Intervention With Telephone Counseling for Mid-Aged and Older Adults: A Randomized Controlled Pilot Trial. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2017 Mar 06;5(3):e28. doi: 10.2196/mhealth.6967. https://mhealth.jmir.org/2017/3/e28/ v5i3e28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cadmus-Bertram LA, Marcus BH, Patterson RE, Parker BA, Morey BL. Randomized Trial of a Fitbit-Based Physical Activity Intervention for Women. Am J Prev Med. 2015 Sep;49(3):414–8. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.01.020. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/26071863 .S0749-3797(15)00044-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Godino JG, Watkinson C, Corder K, Marteau TM, Sutton S, Sharp SJ, Griffin SJ, van Sluijs EMF. Impact of personalised feedback about physical activity on change in objectively measured physical activity (the FAB study): a randomised controlled trial. PLoS One. 2013 Sep 16;8(9):e75398. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0075398. http://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0075398 .PONE-D-13-22387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hurling R, Catt M, Boni Marco De, Fairley BW, Hurst T, Murray P, Richardson A, Sodhi JS. Using internet and mobile phone technology to deliver an automated physical activity program: randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2007 Apr 27;9(2):e7. doi: 10.2196/jmir.9.2.e7. https://www.jmir.org/2007/2/e7/ v9i2e7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jakicic JM, Davis KK, Rogers RJ, King WC, Marcus MD, Helsel D, Rickman AD, Wahed AS, Belle SH. Effect of Wearable Technology Combined With a Lifestyle Intervention on Long-term Weight Loss: The IDEA Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2016 Sep 20;316(11):1161–1171. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.12858. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/27654602 .2553448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martin SS, Feldman DI, Blumenthal RS, Jones SR, Post WS, McKibben RA, Michos ED, Ndumele CE, Ratchford EV, Coresh J, Blaha MJ. mActive: A Randomized Clinical Trial of an Automated mHealth Intervention for Physical Activity Promotion. JAHA. 2015 Oct 29;4(11) doi: 10.1161/jaha.115.002239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Melton BF, Buman MP, Vogel RL, Harris BS, Bigham LE. Wearable Devices to Improve Physical Activity and Sleep. Journal of Black Studies. 2016 Jul 27;47(6):610–625. doi: 10.1177/0021934716653349. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Poirier J, Bennett WL, Jerome GJ, Shah NG, Lazo M, Yeh H, Clark JM, Cobb NK. Effectiveness of an Activity Tracker- and Internet-Based Adaptive Walking Program for Adults: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Med Internet Res. 2016 Feb 09;18(2):e34. doi: 10.2196/jmir.5295. https://www.jmir.org/2016/2/e34/ v18i2e34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shrestha M, Combest T, Fonda SJ, Alfonso A, Guerrero A. Effect of an accelerometer on body weight and fitness in overweight and obese active duty soldiers. Mil Med. 2013 Jan;178(1):82–7. doi: 10.7205/milmed-d-12-00275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thompson WG, Kuhle CL, Koepp GA, McCrady-Spitzer SK, Levine JA. "Go4Life" exercise counseling, accelerometer feedback, and activity levels in older people. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2014 May;58(3):314–9. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2014.01.004.S0167-4943(14)00005-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thorndike AN, Mills S, Sonnenberg L, Palakshappa D, Gao T, Pau CT, Regan S. Activity monitor intervention to promote physical activity of physicians-in-training: randomized controlled trial. PLoS One. 2014 Jun 20;9(6):e100251. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0100251. http://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0100251 .PONE-D-14-08116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Handbook C. Undertaking subgroup analyses. United States: John Wiley & Sons Ltd; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ryan R, Hill S. How to GRADE. How to GRADE the quality of the evidence Cochrane Consumers and Communication. 2018 Jul 25; doi: 10.26181/5b57d95632a2c. https://figshare.com/articles/How_to_GRADE/6818894 . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.de Vries HJ, Kooiman TJ, van Ittersum MW, van Brussel M, de Groot M. Do activity monitors increase physical activity in adults with overweight or obesity? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2016 Oct 26;24(10):2078–91. doi: 10.1002/oby.21619. doi: 10.1002/oby.21619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chiauzzi E, Rodarte C, DasMahapatra P. Patient-centered activity monitoring in the self-management of chronic health conditions. BMC Med. 2015 Apr 09;13(1):77. doi: 10.1186/s12916-015-0319-2. https://bmcmedicine.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12916-015-0319-2 .10.1186/s12916-015-0319-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lyons EJ, Lewis ZH, Mayrsohn BG, Rowland JL. Behavior change techniques implemented in electronic lifestyle activity monitors: a systematic content analysis. J Med Internet Res. 2014 Aug 15;16(8):e192. doi: 10.2196/jmir.3469. https://www.jmir.org/2014/8/e192/ v16i8e192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Feehan LM, Geldman J, Sayre EC, Park C, Ezzat AM, Yoo JY, Hamilton CB, Li LC. Accuracy of Fitbit Devices: Systematic Review and Narrative Syntheses of Quantitative Data. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2018 Aug 09;6(8):e10527. doi: 10.2196/10527. https://mhealth.jmir.org/2018/8/e10527/ v6i8e10527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Search strategies.

PICOS criteria for inclusion and exclusion of studies.

Funnel plot showing publication bias.

GRADE Summary of Evidence Table.