Key Points

Question

How are comprehensive ophthalmology practices responding to common ocular complaints from patients during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic as of April 30, 2020?

Findings

In this cross-sectional study of 60 US ophthalmology practices, there were fairly uniform responses to 3 common ocular complaints across comprehensive ophthalmological practices. Private practices were more likely to schedule cataract evaluations and patients with posterior vitreous detachments sooner than university centers, while all practices were likely to ask about COVID-19 symptoms when scheduling urgent visits.

Meaning

These results suggest most practices were complying with the American Academy of Ophthalmology guidelines for scheduling patients during the COVID-19 pandemic.

This cross-sectional study reports practice patterns for common ocular complaints during the initial stage of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic among comprehensive ophthalmology practices in the US.

Abstract

Importance

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has drastically changed how comprehensive ophthalmology practices care for patients.

Objective

To report practice patterns for common ocular complaints during the initial stage of the COVID-19 pandemic among comprehensive ophthalmology practices in the US.

Design, Setting, and Participants

In this cross-sectional study, 40 private practices and 20 university centers were randomly selected from 4 regions across the US. Data were collected on April 29 and 30, 2020.

Interventions

Investigators placed telephone calls to each ophthalmology practice office. Responses to 3 clinical scenarios—refraction request, cataract evaluation, and symptoms of a posterior vitreous detachment—were compared regionally and between private and university centers.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary measure was time to next appointment for each of the 3 scenarios. Secondary measures included use of telemedicine and advertisement of COVID-19 precautions.

Results

Of the 40 private practices, 2 (5%) were closed, 24 (60%) were only seeing urgent patients, and 14 (35%) remained open to all patients. Of the 20 university centers, 2 (10%) were closed, 17 (85%) were only seeing urgent patients, and 1 (5%) remained open to all patients. There were no differences for any telemedicine metric. University centers were more likely than private practices to mention preparations to limit the spread of COVID-19 (17 of 20 [85%] vs 14 of 40 [35%]; mean difference, 0.41; 95% CI, 0.26-0.65; P < .001). Private practices had a faster next available appointment for cataract evaluations than university centers, with a mean (SD) time to visit of 22.1 (27.0) days vs 75.5 (46.1) days (mean difference, 53.4; 95% CI, 23.1-83.7; P < .001). Private practices were also more likely than university centers to be available to see patients with flashes and floaters (30 of 40 [75%] vs 8 of 20 [40%]; mean difference, 0.42; 95% CI, 0.22-0.79; P = .01).

Conclusions and Relevance

In this cross-sectional study of investigator telephone calls to ophthalmology practice offices, there were uniform recommendations for the 3 routine ophthalmic complaints. Private practices had shorter times to next available appointment for cataract extraction and were more likely to evaluate posterior vitreous detachment symptoms. As there has not been a study examining these practice patterns before the COVID-19 pandemic, the relevance of these findings on public health is yet to be determined.

Introduction

The current coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic caused by the novel severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 has led to drastic changes across the world, especially in the setting of close human interaction. The virus can lead to substantial morbidity and mortality, with reported mortality rates ranging from 0.75% to 3.0%.1,2,3,4 Across outpatient medicine, all specialties have considerably altered practice patterns, focusing on acute or emergent care to ensure safety of both patients and health care workers and to preserve medical equipment and supplies.5,6 Ophthalmology, in particular, has seen perhaps the greatest decrease in outpatient visits among all medical specialties.7,8

On March 18, 2020, the American Academy of Ophthalmology (AAO) issued the following statement:

The American Academy of Ophthalmology strongly recommends that all ophthalmologists provide only urgent or emergent care. This includes both office-based care and surgical care. The Academy recognizes that “urgency” is determined by physician judgment and must always take into account individual patient medical and social circumstances.9

They recommended all ophthalmologists cease to provide any treatment other than urgent or emergent care. There are several ophthalmologic emergencies that have both vision-threatening and life-threatening implications and necessitate urgent evaluation, such as retinal detachments, acute angle-closure glaucoma, acute diplopia, and central retinal artery occlusions.10,11,12,13 Generally, refractive disorders and cataract surgery are not considered emergencies, although there are specific scenarios where they may precipitate or signify severe ocular sequalae, such as acute hyperopia, congenital cataracts leading to amblyopia, and age-related cataracts leading to glaucomatous damage or precluding patients from performing self-care or driving.14,15,16 Evaluation of flashes and floaters, given their association with posterior vitreous detachment (PVD), retinal tear, and retinal detachment, are considered more urgent complaints.

The goal of this study was to evaluate practice patterns and time to first available appointment of comprehensive ophthalmology practices across the US during the COVID-19 pandemic using scripted telephone calls of 3 ophthalmological scenarios: refractive consultation, cataract consultation, and symptoms of a PVD. Using these scripts, we sought to identify if practices were complying with the AAO statement on COVID-19.

Methods

This study is in compliance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, received prospective approval from the Wills Eye Hospital institutional review board, and adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. The institutional review board waived the need for informed consent for center respondents, and all data were deidentified during data analysis.

The primary goal of this study was to assess the responses of comprehensive ophthalmology practices, both in university and private practice settings, to common ophthalmologic complaints during the COVID-19 pandemic using scripted telephone calls, including refraction request, cataract evaluation, and flashes and floaters. We excluded any ophthalmologic subspecialty practices, such as glaucoma, cornea, neuro-ophthalmology, pediatrics, or retina.

As previously described in the dermatologic literature, the methodology of calling practices and querying wait times for appointments using predetermined scripts has been well validated.17,18,19 To adequately assess the responses across the US, we divided the country into 4 regions: Northeast, South, Midwest, and West. Within each region, we identified 10 comprehensive private practices and 5 university medical centers with comprehensive ophthalmology practices for a total of 60 comprehensive ophthalmology practices. A university medical center was defined as a practice affiliated with a teaching hospital and an ophthalmology residency program; all other practices were considered private practice. The practices were chosen using a random search of the AAO Find an Ophthalmologist website within the specific region of the country.20 Specifically, we generated a list of ophthalmologists within 100 miles from each of the following cities: Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; New York, New York; Boston, Massachusetts; Durham, North Carolina; Miami, Florida; St Louis, Missouri; Chicago, Illinois; Minneapolis, Minnesota; Dallas, Texas; Houston, Texas; Denver, Colorado; Los Angeles, California; San Diego, California; San Francisco, California; Portland, Oregon; and Seattle, Washington. Using a random number generator, practices corresponding to the random number on each list were selected and divided evenly by the different regions in the country.

Investigators placed telephone calls to the publicly available telephone number listed for each comprehensive practice. An office was considered closed if there was no answer after 2 attempts during normal listed business hours or if a voice message was played conveying closure of the practice. If the call was answered, each author had a specific script to use when addressing the practice (eMethods in the Supplement). The first script involved a patient requesting an updated refraction as their current refraction was outdated. The second script involved a patient interested in a cataract surgery consultation. More specifically, this scenario had the patient inform the receptionist that their primary optometrist had diagnosed them with a cataract several months ago and they were interested in surgery. There was no acute worsening of their vision nor any eye pain. The third script involved a patient describing symptoms of a PVD in 1 eye, which represents a potentially urgent ophthalmological problem. The same author called each practice with the same script to allow for a degree of uniformity (R. I., M. Z., and Q. E. C., respectively). When speaking to the telephone respondent, the author asked if the practice was currently open to all appointments, only urgent or emergent appointments, or closed and currently delaying all appointments. The caller also asked if a telemedicine visit would be available. If able, the caller then asked for the soonest appointment offered by the practice. All practices were called during business hours on April 29 or April 30, 2020, during the COVID-19 pandemic in the US. The wait time for each call was recorded as well as if the telephone respondent inquired about symptoms consistent with active COVID-19 exposure. Additionally, the author recorded if the receptionist, physician, or practice’s website mentioned any measures taken to implement social distancing or improve sterilization practices (eg, virtual waiting room, limited hours, required usage of masks by all personnel and patients). Any appointments offered to the callers were declined. All callers were told they would be paying with money if insurance was required for an appointment.

Analyses comparing regional differences as well as the differences in the prevalence of COVID-19 as of April 30, 2020, in practice response were also performed.21 JMP software version 15.0 (SAS Institute) was used for statistical analysis and was performed on May 1, 2020, and again on June 27, 2020. For comparisons between continuous variables, the Wilcoxon rank sum test was performed. Group comparisons of the categorical data were performed using the Fisher exact test. Statistical significance was set at a P value less than .05, and all P values were 2-tailed.

Results

Practice Openings and Availability

A total of 60 practices were included. Of the 40 private practices, 2 (5%) were closed, 24 (60%) were only seeing urgent patients, and 14 (35%) remained open to all patients. Of the 20 university centers, 2 (10%) were closed, 17 (85%) were only seeing urgent patients, and 1 (5%) remained open to all patients (Table 1).

Table 1. Responses for All 3 Clinical Scenarios Among Private Practice Comprehensive Practices and University Centers During the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Pandemic.

| Characteristic | No. (%) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Private (n = 40) | University (n = 20) | ||

| Offices | |||

| Open for telemedicine visits | 7 (18) | 3 (15) | .81 |

| Open for all patient encounters | 14 (35) | 1 (5) | .04 |

| Normal office hours | 11 (28) | 10 (50) | .10 |

| Office able to see patients for refraction visit | 22 (55) | 8 (40) | .27 |

| Time to next available refraction appointment, mean (SD), d | 22.5 (16.7) | 41 (36.6) | .28 |

| Office able to see patients for cataract consultation visit | 33 (83) | 12 (60) | .11 |

| Time to next available cataract consultation, mean (SD), d | 22.1 (27.0) | 75.5 (46.1) | <.001 |

| Office able to see patients for PVD visit | 30 (75) | 8 (40) | .01 |

| Time to next available PVD appointment, mean (SD), d | 1.0 (0.8) | 1.1 (0.4) | .24 |

| Receptionist/website mention preparedness for COVID-19 | 14 (35) | 17 (85) | <.001 |

| Receptionist asked about COVID-19 symptoms, No./total No. (%) | |||

| For refraction | 1/40 (3) | 2/20 (10) | .26 |

| For cataract | 1/40 (3) | 1/13 (8) | .46 |

| For PVD | 20/35 (57) | 10/16 (63) | .77 |

Abbreviation: PVD, posterior vitreous detachment.

Use of Telemedicine

There were no significant differences between private and university centers in regards to the use of telemedicine (Table 1). A total of 7 of 40 private practices (18%) offered telemedicine services, while 3 of 15 university centers (20%) were offering telemedicine visits (mean difference [MD], 0.17; 95% CI, 0.10-0.23; P = .81). When analyzed by region or by COVID-19 prevalence, there were no differences in telemedicine services identified by practice setting (Table 2 and Table 3).

Table 2. Responses for All 3 Clinical Scenarios Among Private Practice Comprehensive Practices and Academic Centers During the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Pandemic.

| Characteristic | No. (%) | P value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Northeast (n = 15) | Midwest (n = 15) | South (n = 15) | West (n = 15) | ||

| Offices | |||||

| Open for telemedicine visits | 3 (20) | 3 (20) | 1 (7) | 3 (20) | .70 |

| Open for all patient encounters | 3 (20) | 1 (7) | 7 (47) | 4 (27) | .04 |

| Normal office hours | 3 (20) | 6 (40) | 8 (53) | 4 (27) | .23 |

| Office able to see patients for refraction visit | 11 (73) | 6 (40) | 7 (47) | 6 (40) | .21 |

| Time to next available refraction appointment, mean (SD), d | 36.9 (34.9) | 20.2 (11.0) | 19.7 (10.7) | 29.8 (19.5) | .81 |

| Office able to see patients for cataract consultation visit | 12 (80) | 11 (73) | 14 (93) | 8 (53) | .08 |

| Time to next available cataract consultation, mean (SD), d | 52.3 (50.0) | 43.9 (42.6) | 23.7 (31.2) | 24.1 (30.3) | .09 |

| Office able to see patients for PVD visit | 8 (53) | 10 (67) | 10 (67) | 10 (67) | .84 |

| Time to next available PVD appointment, mean (SD), d | 1.1 (0.4) | 0.8 (0.4) | 1.4 (1.2) | 0.8 (0.4) | .24 |

| Receptionist/website mention preparedness for COVID-19 | 5 (33) | 5 (33) | 9 (60) | 12 (80) | .03 |

| Receptionist asked about COVID-19 symptoms, No./total No. (%) | |||||

| For refraction | 2/15 (13) | 0 | 1/15 (7) | 0 | .28 |

| For cataract | 0 | 0 | 2/15 (14) | 0 | .16 |

| For PVD | 7/12 (58) | 8/12 (67) | 6/13 (46) | 9/14 (64) | .72 |

Abbreviation: PVD, posterior vitreous detachment.

Table 3. Responses for All 3 Clinical Scenarios Among Private Practices and University Centers During the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Pandemic by Geographic Region.

| Characteristic | Northeast | Midwest | South | West | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. (%) | P value | No. (%) | P value | No. (%) | P value | No. (%) | P value | |||||

| Private (n = 10) | Academic (n = 5) | Private (n = 10) | Academic (n = 5) | Private (n = 10) | Academic (n = 5) | Private (n = 10) | Academic (n = 5) | |||||

| Offices | ||||||||||||

| Open for telemedicine visits | 1 (10) | 2 (40) | .24 | 2 (20) | 1 (20) | >.99 | 1 (10) | 0 | >.99 | 3 (30) | 0 | .51 |

| Open for all patient encounters | 3 (30) | 0 | .26 | 1 (10) | 0 | >.99 | 6 (60) | 1 (20) | .28 | 4 (40) | 0 | .17 |

| Normal office hours | 3 (30) | 0 | .51 | 2 (20) | 4 (80) | .09 | 4 (40) | 4 (80) | .28 | 2 (20) | 2 (40) | .57 |

| Office able to see patients for refraction visit | 7 (70) | 4 (80) | >.99 | 6 (60) | 0 | .04 | 4 (40) | 3 (60) | .61 | 5 (50) | 1 (20) | .58 |

| Time to next available refraction appointment, mean (SD), d | 23 (21.6) | 62.3 (43.4) | .21 | 20.2 (11.0) | NA | NA | 18.3 (8.1) | 21.7 (15.3) | .48 | 32.2 (20.8) | 18.0 (0) | .38 |

| Office able to see patients for cataract consultation visit | 9 (90) | 3 (60) | .24 | 9 (90) | 2 (40) | .08 | 9 (90) | 5 (100) | >.99 | 6 (60) | 2 (40) | .61 |

| Time to next available cataract consultation, mean (SD), d | 31.7 (38.8) | 114.0 (10.1) | .03 | 26.7 (20.7) | 121.5 (6.4) | .03 | 9.6 (10.0) | 49.2 (41.1) | .02 | 19.7 (30.6) | 37.5 (36.0) | .39 |

| Office able to see patients for PVD visit | 7 (70) | 1 (20) | .12 | 7 (70) | 3 (60) | >.99 | 8 (80) | 2 (40) | .25 | 8 (80) | 2 (40) | .25 |

| Time to next available PVD appointment, mean (SD), d | 1.0 (0) | 2.0 (0) | .008 | 0.7 (0.5) | 1.0 (0) | .33 | 1.5 (1.3) | 1.0 (0) | .75 | 0.8 (0.5) | 1.0 (0) | .45 |

Abbreviations: NA, not applicable; PVD, posterior vitreous detachment.

Time to Next Available Appointment

Among the 40 private practices, 22 (55%) offered to schedule the refractive error scenario compared with 8 of 20 university centers (40%; P = .27). There was no difference in mean (SD) time to scheduling for refractive error in private practices compared with university centers (22.5 [16.7] days vs 41.0 [36.6] days; MD, 18.5; 95% CI, 13.4-48.5; P = .28). Among the 40 private practices, 33 (83%) offered to schedule the cataract evaluation scenario compared with 12 of 20 university centers (60%; MD, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.60-0.83; P = .11). Of note, private practices scheduled the cataract evaluation after a mean (SD) of 22.1 (27.0) days, whereas university centers scheduled the visit after a mean (SD) of 75.5 (46.1) days (MD, 53.4; 95% CI, 23.1-83.7; P < .001). There were more private practices that offered to schedule a patient with symptoms concerning for a PVD compared with university centers (30 of 40 [75%] vs 8 of 20 [40%]; MD, 0.42; 95% CI, 0.22-0.79; P = .01). However, there was no difference in the time to the appointment between private practices and university centers for PVD complaints (mean [SD] time, 1.0 [0.8] days vs 1.1 [0.4] days; MD, 0.10; 95% CI, −0.42 to 0.42; P = .24) (Table 1).

For the PVD scenario, 22 of 60 practices (37%) did not offer an appointment, and 11 of these 22 practices (50%) told the caller they would call back by the end of the day with guidance but did not return the telephone call. Of these 22 practices, 10 (45%) were university centers, comprising half of the university cohort. Additionally, 5 practices (23%), all of which were university centers, told the caller to report to the closest emergency department, 3 (14%) did not accept money instead of insurance, and 3 (14%) simply stated they do not deal with this type of problem.

Use of Screening Methods

When evaluating callers for symptoms consistent with COVID-19 infection, there were no significant differences between private or university centers for any scenario. Only 3 of 56 practices (5%) asked about symptoms in the refraction clinical scenario and 2 of 49 (4%) for cataract surgery scenario. However, 30 of 51 practices (59%) asked COVID-19 screening questions when scheduling PVD visits, including 20 of 35 private practices (57%) and 10 of 16 university centers (63%). University centers were also more likely than private practices to display or announce preparations in place to combat the spread of COVID-19 (17 of 20 [85%] vs 14 of 40 [35%]; mean difference, 0.41; 95% CI, 0.26-0.65; P < .001), with increased hand hygiene, use of masks, limited visitors, or increased personal protective equipment use for clinicians (Table 1).

Regional Comparisons

The responses between the 4 different geographic regions (Northeast, South, Midwest, and West) are detailed in Table 2. Briefly, ophthalmology practices in the South were more likely than other regions to be open to all patients (South, 7 of 15 [47%]; Northeast, 3 of 15 [20%]; Midwest, 1 of 15 [7%]; West, 4 of 15 [27%]; P = .04), and practices in the West were more likely than other regions to announce preparedness for decreasing the spread of COVID-19 (West, 12 of 15 [80%]; Northeast, 5 of 15 [33%]; South, 5 of 15 [33%]; Midwest, 9 of 15 [60%]; P = .03). There were no other statistical differences identified between the regions. The geographic regions were further subdivided based on private or university practice, and the results are presented in Table 3.

Practice Patterns and COVID-19 Disease Prevalence

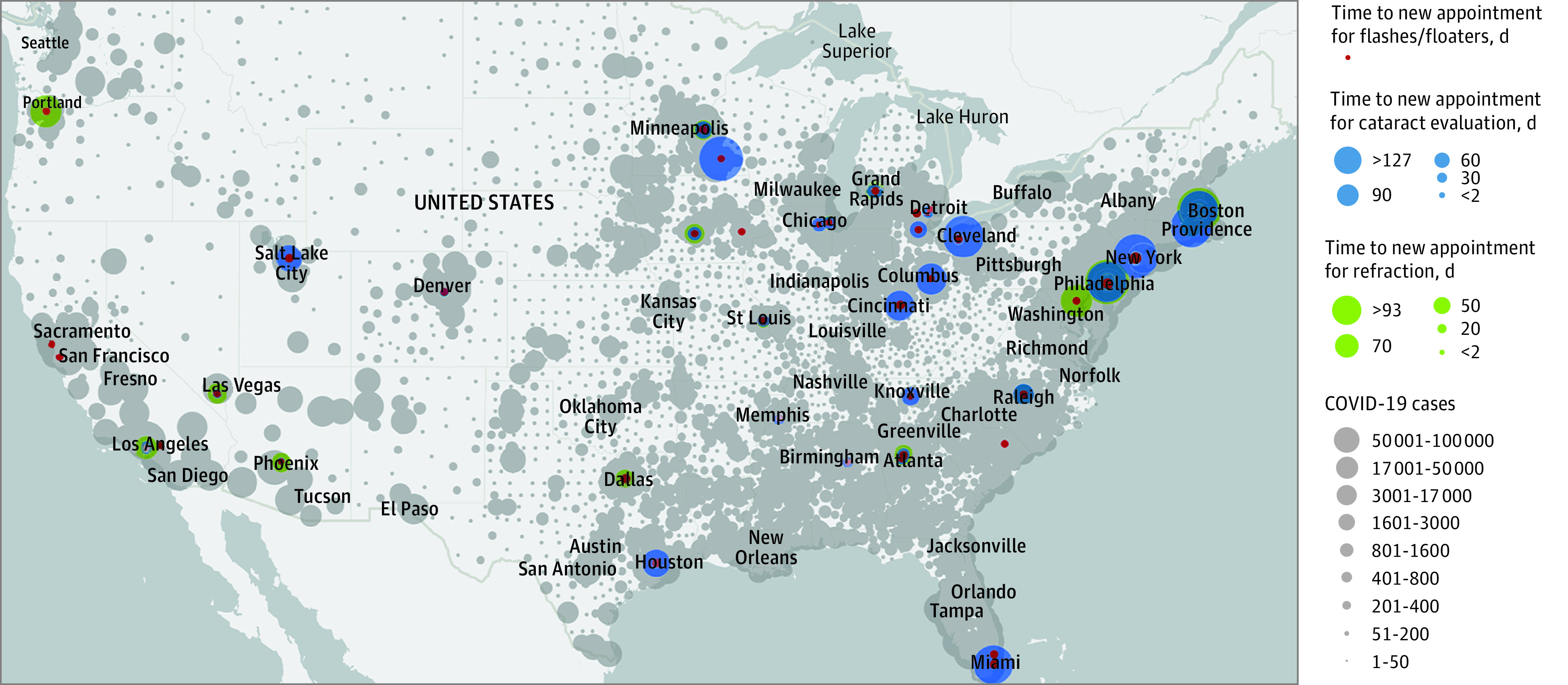

When comparing US practices located in the areas with the highest prevalence of COVID-19 as of April 30, 2020, there were no significant differences in response to any of the patient scripts (Table 4). The Figure maps the prevalence of COVID-19 as of April 30, 2020, and overlays the results of time to scheduling refraction, cataract, and PVD appointments.

Table 4. Responses for All 3 Clinical Scenarios Among the 30 Practices Within Areas of Higher Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Prevalence and 30 Practices in Areas of Lower COVID-19 Prevalence.

| Characteristic | COVID-19 prevalence, No. (%) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Higher (n = 30) | Lower (n = 30) | ||

| Offices | |||

| Open for telemedicine visits | 5 (17) | 5 (17) | >.99 |

| Open for all patient encounters | 7 (23) | 8 (27) | .53 |

| Normal office hours | 9 (30) | 12 (40) | .59 |

| Office able to see patients for refraction visit | 16 (53) | 14 (47) | .80 |

| Time to next available refraction appointment, mean (SD), d | 29.7 (29.6) | 26.4 (17.5) | .86 |

| Office able to see patients for cataract consultation visit | 25 (83) | 20 (67) | .23 |

| Time to next available cataract consultation, mean (SD), d | 40.0 (43.9) | 31.6 (36.6) | .68 |

| Office able to see patients for PVD visit | 18 (60) | 20 (67) | .79 |

| Time to next available PVD appointment, mean (SD), d | 1.1 (0.2) | 0.9 (0.7) | .25 |

| Receptionist/website mention preparedness for COVID-19 | 14 (47) | 17 (57) | .61 |

| Receptionist asked about COVID-19 symptoms, No./total No. (%) | |||

| For refraction | 2/30 (7) | 1/30 (3) | >.99 |

| For cataract | 1/26 (4) | 1/29 (4) | >.99 |

| For PVD | 15/26 (58) | 15/25 (60) | >.99 |

Abbreviation: PVD, posterior vitreous detachment.

Figure. Heat Map of the US With Prevalence of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Infections as of April 30, 2020.

The map overlays displays of time to refraction request, cataract evaluation, and posterior vitreous detachment examination for each practice within this study. Larger dots represent higher prevalence of COVID-19 infection and longer times to evaluation for each clinical scenario.

Discussion

In this study, we report practice patterns of comprehensive ophthalmology practices during the COVID-19 pandemic in regards to 3 common clinical scenarios of differing clinical urgency. This study identifies that comprehensive ophthalmologists appear to be abiding by guidelines suggesting evaluation for only urgent patients. Our findings mirror a recent report looking at dermatology practices,22 another outpatient-based subspecialty. In summary, more private practices were open to all patients during the COVID-19 pandemic while university centers were more likely to only see urgent patients, and private practice centers were seeing patients sooner for both nonurgent and semiurgent ophthalmologic complaints.

When broken down by region, there were essentially no differences in practice patterns, other than practices in the South were seeing patients for cataract consultations sooner than the rest of the country. Additionally, there did not appear to be any difference in responses among centers located in regions with higher COVID-19 prevalence compared with regions with a lower prevalence. Private practices were more likely to see patients for cataract consultations sooner than university centers and were more likely to see patients with PVD symptoms, but there was no difference in the time to new refraction visits between the cohorts. Despite scheduling these patients sooner than their regionally matched university counterparts, the ophthalmology private practices were, on average, scheduling patients with nonurgent and emergent conditions beyond the period of time set in place for most states to begin resuming elective surgeries. Thus, while appointment times may have been shorter, they appear to remain in line with the AAO’s and public health officials’ risk mitigation strategies.

Telemedicine has emerged as an important resource for patient care during the COVID-19 pandemic. Although this study took place nearly 1 month following the AAO’s call for reduced office visits and a recommendation to limit our care to urgent patients only, there were relatively few practices performing telemedicine visits, with 7 of 40 private practice centers (18%) and 3 of 15 university centers (15%) doing so. Telemedicine is a validated practice for specific ophthalmic complaints, especially if implemented in the appropriate settings.23,24 Interestingly, in a previous survey study regarding comfortability with telemedicine use and interpreting patient photographs online, 59% of respondents had low confidence in providing patient care via telemedicine.25 The current infrastructure of the health care system, along with the potential logistical restrictions (establishing a secure system to communicate with patients in such a short timeframe), worries about potential reimbursement, and concern for medicolegal liabilities, may help to explain the hesitancy of physicians to adopt a telemedicine system for their patients. Additionally, the scripted complaints in this study are not amenable to telehealth visits and certainly may have influenced the responses of the receptionists and physicians responding to the scripts.

Use of COVID-19 screening methods has also emerged as an important practice pattern during the pandemic. This study was conducted near the peak of the initial stage of the COVID-19 pandemic in the US. When scheduling patients with nonurgent complaints (ie, refraction and cataract evaluation), most appointments were made several weeks from the time the call was conducted. In these scenarios, the authors were rarely asked for symptoms consistent with active infection with COVID-19. However, when calls were placed to the same centers in the urgent PVD scenario, there was a large increase in the number of offices asking about COVID-19 symptoms (20 of 35 private practices [57%] and 10 of 16 university centers [63%]). These visits were routinely scheduled within 0 to 2 days, and the office staff was likely instructed to identify all potentially sick patients during the scheduling call as opposed to using these screening questions for appointments made several weeks in advance. In the nonurgent case scenarios, we are unable to answer if the practices would subsequently query patients about symptoms closer to their appointments. Interestingly, university centers more frequently outlined on their website and/or during the telephone conversation specific safety measures they were using compared with private practices.

Limitations

There are several limitations in our study. Scripted callers were used rather than real patients with real complaints. However, these methods have been validated in the past.17,19 This study also took place 1 month after the AAO issued a mandate urging only emergent care from all health care professionals. At the time the telephone calls were conducted, there were vastly different approaches to public health safety as well as health care practices among the states in the different regions of our trial. Although these differing approaches to health care may have influenced potential responses, at the time of calling, all states involved in the study had stay-at-home guidelines in place.26 Another limitation is that some university centers may have diverted resources to more urgent specialties in their respective institutions (eg, intensive care units, emergency departments), which could have ultimately affected their outpatient clinic management and their responses. However, dynamic systems changes during the COVID-19 pandemic may influence practice management variables, and examining these effects was one of the goals of the study. While there were more university general ophthalmology practices that were closed or unable to schedule a patient with symptoms concerning for a PVD compared with private practices, the university practices may have had an alternative phone number for the university subspecialty departments. Furthermore, although we conducted 180 unique telephone conversations spread through 4 regions of the country, it is possible that a different population of practices may have resulted in different responses. Additionally, to our knowledge, a study comparing wait times between university and private practices for the scenarios presented in the absence of a pandemic has not been performed. However, it has been previously reported that private practices have faster times to next available appointments for blepharoplasty consultations compared with university centers.27 Since the differences in responses prior to COVID-19 to these clinical scenarios described have not been studied, to our knowledge, we cannot be certain that differences noted between practice centers and regions reflect the effect of COVID-19 or are inherent differences in scheduling patterns between private practices and university centers. Moreover, while appointment times may have been shorter for private practices, it is possible that practices may reschedule patients if, when appointment times approach, risk mitigation strategies may favor appointment deferment.

Conclusions

These findings suggest private practices had faster times to schedule cataract consultations during the COVID-19 pandemic and were more likely to see patients with symptoms of a possible PVD than university centers. Interestingly, areas with higher prevalence of COVID-19 had no difference for any metric for any of the scenarios presented, but practices were more likely to ask about COVID-19 symptoms when scheduling more urgent appointments. This study identifies that most comprehensive ophthalmologists were abiding by guidelines suggesting evaluation for only urgent patients, with minimal differences between private practices and university centers.

eMethods. Scripts for phone calls.

References

- 1.Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395(10229):1054-1062. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Du R-H, Liang L-R, Yang C-Q, et al. Predictors of mortality for patients with COVID-19 pneumonia caused by SARS-CoV-2: a prospective cohort study. Eur Respir J. 2020;55(5):2000524. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00524-2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Han Q, Lin Q, Jin S, You L. Coronavirus 2019-nCoV: a brief perspective from the front line. J Infect. 2020;80(4):373-377. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.02.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang L, Li J, Guo S, et al. Real-time estimation and prediction of mortality caused by COVID-19 with patient information based algorithm. Sci Total Environ. 2020;727:138394. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.American College of Surgeons COVID-19: recommendations for management of elective surgical procedures. Accessed May 3, 2020. https://www.facs.org/covid-19/clinical-guidance/elective-surgery

- 6.AMA resources available to physicians to navigate COVID-19 pandemic. News release. American Medical Association. March 20, 2020. Accessed May 3, 2020. https://www.ama-assn.org/press-center/press-releases/ama-resources-available-physicians-navigate-covid-19-pandemic

- 7.Mehrotra A, Chernew M, Linetsky D, Hatch H, Cutler D The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on outpatient visits: a rebound emerges. Accessed May 3, 2020. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/2020/apr/impact-covid-19-outpatient-visits

- 8.Analysis: ophthalmology lost more patient volume due to COVID-19 than any other specialty. Accessed May 13, 2020. https://eyewire.news/articles/analysis-55-percent-fewer-americans-sought-hospital-care-in-march-april-due-to-covid-19/

- 9.American Academy of Ophthalmology Recommendations for urgent and nonurgent patient care. Accessed May 3, 2020. https://www.aao.org/headline/new-recommendations-urgent-nonurgent-patient-care

- 10.Romaniuk VM. Ocular trauma and other catastrophes. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2013;31(2):399-411. doi: 10.1016/j.emc.2013.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Prasad S. The urgency and site of retinal detachment surgery. Eye (Lond). 2006;20(9):1105-1106. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6702144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Biousse V, Nahab F, Newman NJ. Management of acute retinal ischemia: follow the guidelines! Ophthalmology. 2018;125(10):1597-1607. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2018.03.054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Collignon NJ. Emergencies in glaucoma: a review. Bull Soc Belge Ophtalmol. 2005;(296):71-81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khan A. Refractive emergency. Surv Ophthalmol. 1996;40(5):405-406. doi: 10.1016/S0039-6257(96)80070-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.American Academy of Ophthalmology List of urgent and emergent ophthalmic procedures. Accessed May 10, 2020. https://www.aao.org/headline/list-of-urgent-emergent-ophthalmic-procedures

- 16.Li L, Wang Y, Xue C. Effect of timing of initial cataract surgery, compliance to amblyopia therapy on outcomes of secondary intraocular lens implantation in Chinese children: a retrospective case series. J Ophthalmol. Published online March 22, 2018. doi: 10.1155/2018/2909024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tsang MW, Resneck JS Jr. Even patients with changing moles face long dermatology appointment wait-times: a study of simulated patient calls to dermatologists. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55(1):54-58. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2006.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tan S, Seiger K, Renehan P, Mostaghimi A. Trends in private equity acquisition of dermatology practices in the United States. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155(9):1013-1021. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.1634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Resneck JS Jr, Lipton S, Pletcher MJ. Short wait times for patients seeking cosmetic botulinum toxin appointments with dermatologists. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57(6):985-989. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2007.07.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.American Academy of Ophthalmology Find an ophthalmologist. Accessed May 3, 2020. https://secure.aao.org/aao/find-ophthalmologist

- 21.Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center COVID-19 United States cases by county. Accessed May 3, 2020. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/us-map

- 22.Muddasani S, Housholder A, Fleischer AB. An assessment of United States dermatology practices during the COVID-19 outbreak. J Dermatolog Treat. 2020;31(5):436-438. doi: 10.1080/09546634.2020.1750556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morse AR. Telemedicine in ophthalmology: promise and pitfalls. Ophthalmology. 2014;121(4):809-811. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2013.10.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Starr MR, Barkmeier AJ, Engman SJ, Kitzmann A, Bakri SJ. Telemedicine in the management of exudative age-related macular degeneration within an integrated health care system. Am J Ophthalmol. 2019;208:206-210. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2019.03.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Woodward MA, Ple-Plakon P, Blachley T, et al. Eye care providers’ attitudes towards tele-ophthalmology. Telemed J E Health. 2015;21(4):271-273. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2014.0115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.The Council of State Governments COVID-19 resources for state leaders. Accessed May 3, 2020. https://web.csg.org/covid19/executive-orders/

- 27.Knezevic A, Yoon MK. Differences in wait times for cosmetic blepharoplasty by ASOPRS members. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2018;34(3):222-224. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0000000000000922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods. Scripts for phone calls.