Abstract

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is one of the most common malignancies. The current treatments of metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC) are ineffective and the bottleneck problem. It is of significance to explore effective new therapeutic strategies to eradicate mCRC. Photothermal therapy (PTT) is an emerging technology for tumor therapy, with the potential in the treatment of mCRC. In this review, the current treatment approaches to mCRC including surgery, radiotherapy, chemotherapy interventional therapy, biotherapy, and photothermal therapy are reviewed. In addition, we will focus on the various kinds of nanomaterials used in PTT for the treatment of CRC both in vitro and in vivo models. In conclusion, we will summarize the combined application of PTT with other theranostic methods, and propose future research directions of PTT in the treatment of CRC.

Keywords: Mucinous adenocarcinoma, colorectal carcinoma, photothermal therapy, colorectal cancer

Introduction

The morbidity and mortality rate of colorectal cancer (CRC) ranked third in males and second in females, is high [1]. As the age of the average population increased, accompanied by environmental factors such as poor diet, smoking, low physical activity, and obesity, the incidence in CRC has increased rapidly since the 1950s [2,3]. In recent years, with the development of medicine and the application of tumor screening, the rate of CRC in the elderly has gradually reduced. On the other hand, the incidence of CRC in the younger population under 50 years of age has increased significantly [4]. This is because people generally would not screen if there was not a family history, leading to an advanced and less treatable form of CRC [5].

The treatment of patients with mCRC is one of the bottleneck problems. Distant metastases of CRC often occur first in the liver, the lung, and the peritoneum, followed by rarer distant metastases in the brain, the bone, and the retroperitoneal lymph nodes [6]. The liver is the most common site of CRC metastases, because about 30% of mCRC patients have liver metastases and 50% of patients with liver metastases also have other metastases during the disease [7]. Lung metastasis is the second most common form of colorectal cancer metastases, occurring in about 11% of CRC patients [8,9]. Lung metastasis from rectal cancer is more common than from colon cancer, because rectal cancer could spread directly to the systemic circulation via the internal iliac veins without passing through the portal vein [10]. Peritoneal metastasis occurs in about 4-13% of CRC patients [11,12], which was once considered a form of systemic distant metastases and a terminal state with poor prognosis [13]. At present, the treatment pattern of early and progressive CRC is a comprehensive treatment consisting of surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy. This comprehensive treatment resulted in a significant increase in 5-year survival rate of 71% in the early stage and 41% in the progressive stage [6]. However, the 5-year survival rate of patients with advanced colorectal cancer, namely metastatic CRC (mCRC), even after surgery, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, and other treatments is only 14% [6]. Therefore, exploring effective new treatment strategies is considerable for the treatment of mCRC.

This article reviews the current status of treatment of mCRC, including surgery, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, interventional therapy, biotherapy, and photothermal therapy. In addition, various photothermal conversion materials for CRC treatment using cellular and animal models, and the combination of PTT with other theranostic methods are evaluated.

Canonical treatment of mCRC

Currently, the main treatment methods of mCRC include: surgery [14-16]; radiotherapy [17,18]; chemotherapy [19-22]; biotherapy [23-31] and interventional therapy [32]. Depending on the severity of the disease, mCRC can be divided into two categories, oligometastatic CRC (localized mCRC) and extensive mCRC. Oligometastatic CRC is characterized by a disease state with less than 2 metastatic sites and 5 metastatic tumors. However, when the metastatic sites and numbers are over 2 and 5, respectively, mCRC is more severe and referred to as extensive mCRC. The goal for treating oligometastatic CRC is to achieve complete resection and tumor-free status by surgery or radiotherapy, while the goal for treating extensive mCRC is to achieve disease control through chemotherapy and biotherapy, as well as symptom relief. Table 1 compares the indications, complications, and outcomes of the current mCRC treatment methods.

Table 1.

Treatment of mCRC

| Category | Program | Indications | Complications | Efficacy | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surgical treatment (Primary resection +) | Partial hepatectomy | Except for unresectable extrahepatic disease, tumor involvement over 70% of liver, liver failure and intolerance to surgery | Liver failure, postoperative bleeding, heart failure, systemic sepsis | The 5-year survival rate in patients with surgery combined with chemotherapy is 50% | [14,33,34] |

| Partial pneumonectomy | Feasible complete resection, control of the primary tumor | Respiratory secretion retention, atelectasis, bronchopleural fistula | The 5-year survival rate is 25% to 35% | [8,35,36] | |

| CRS+HIPEC | Well/moderately differentiation without extraperitoneal metastasis | Anastomotic fistula, bleeding, wound infection, neutropenia | The 5-year survival rate is 31% | [15,37] | |

| Radiotherapy | Traditional radiotherapy | A palliative treatment for extensive mCRC | Radiation damage | Local symptom remission | [17,18] |

| SBRT | Oligometastatic CRC | Radiation hepatitis/pneumonia/enteritis | Improvement of local control rate | [17,18] | |

| Chemotherapy | FOLFIRI | A palliative/conversion/adjuvant therapy for mCRC | Febrile neutropenia, nausea, vomiting | The median OS is 16.2 months | [19,38] |

| FOLFOX | A palliative/conversion/adjuvant therapy for mCRC | Neutropenia, low platelet count, peripheral neuropathy | The median OS is 19.5 months | [20,34] | |

| CapeOX | A palliative/conversion/adjuvant therapy for mCRC | Diarrhea, hand-foot syndrome, peripheral neuropathy | The median OS is 16.3 months | [21,39] | |

| FOLFOXIRI | A palliative/conversion/adjuvant therapy for mCRC | Neutropenia, diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, peripheral neurotoxicity | The median OS is 19.6 months | [22,40] | |

| Interventional therapy | Radiofrequency ablation, cryoablation or microwave ablation | A palliative/conversion/adjuvant therapy for mCRC | Local recurrence, low fever, abdominal pain, muscle pain, nausea, vomiting, liver damage | Improvement of progression-free survival | [41,42] |

| Chemical/radiotherapy pharmaceuticals embolization or topical use of chemotherapy pharmaceuticals | Extensive mCRC insensitive to canonical chemotherapeutics | Local recurrence, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, liver function damage | Improvement of progression-free survival | [43] | |

| Biotherapy | EGFR targeting monoclonal antibody | K-ras wild-type patients combined with chemotherapy | Rashes, allergic reactions, and hypomagnesemia | Improvement of progression-free survival | [44-46] |

| VEGF targeting monoclonal antibody | Combination with chemotherapy | Hypertension, proteinuria, thromboembolism | Improvement of progression-free survival | [25,46] | |

| Immunity inhibitors | dMMR/MSI-H patients | Lipase concentration and amylase concentration increased | Improvement of progression-free survival | [29-31] |

Surgical treatment

Surgical treatment of mCRC refers to the simultaneous removal of primary and metastatic lesions. Primary resection mainly includes radical resection (R0 resection, no residual tumor cells under the microscope after resection) and palliative resection. The main methods include partial hepatectomy, partial pneumonectomy, and cytoreductive surgery combined with hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (CRS-HIPEC) and retroperitoneal lymphadenectomy.

The liver is the most common metastatic site of CRC, so liver metastasis is the most critical in the treatment of mCRC. For OMD with Colorectal liver metastasis (CLM), the surgical method is primary resection and partial hepatectomy. For OMD CRC patients with liver metastasis, the 5-year survival rate of these patients after local resection was about 30%, which increased up to 50% when combined local resection with postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy (Table 1) [14,33]. The disadvantage of partial hepatectomy is its limited application, for only 20% of patients with liver metastases could be removed surgically [33]. Reasons for inoperable treatment include unresectable extrahepatic disease, the cancerous liver involved is more than 70%, liver failure, and intolerance to surgery [14]. Researches show that 70% of CRC patients undergone partial hepatectomy experience tumor recurrence within 3 years [32,34].

Surgical treatment for patients with lung metastasis involves partial pneumonectomy. The indications for surgical treatment include feasible complete resection, control of the primary tumor, and surgery tolerance [35]. The 5-year survival rate of patients after partial pneumonectomy is 25%-35% [48,49]. This application is limited, since lung metastases are rarely isolated. Single lung metastasis account for only 1.7-7.2% of all mCRC patients with lung metastases [50]. It is expected that patients with mCRC who have undergone partial pneumonectomy would have received partial hepatectomy as well [51]. In addition, the recurrence rate after partial pneumonectomy is high with 80% of patients relapsing within 2 years [50,52].

Peritoneal metastasis is the second most common site of CRC metastasis, which usually cannot be completely removed surgically [15]. However, the metastatic foci of CRC peritoneal metastasis do not usually occur in a single site of the peritoneum, but spread to the adjacent peritoneum to form a diffuse distribution [13], so local resection cannot completely remove the peritoneal metastasis. Currently, the clinical treatment for peritoneal mCRC is cytoreductive surgery (CRS) combined with hyperthermic introperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) [53], namely CRS-HIPEC. CRS involves in the resection of all visible lesions, followed by HIPEC, through which chemotherapy drugs at 42-43°C are intraperitoneally injected during or straight after the operation [13]. CRS-HIPEC has been shown to effectively remove residual lesions in the abdominal cavity and prolong the survival time of patients with peritoneal metastasis through the combination of thermal effect and chemotherapeutics [15]. Since chemotherapeutic drugs need to be distributed uniformly throughout the abdominal cavity to kill the metastases instead of therapeutic targeting just one region, this will inevitably lead to damage of the normal surrounding tissue [54]. CRS-HIPEC has a couple of disadvantages: 1) CRS is complicated with long operation time of up to 8-10 h, making the process difficult to be tolerated by patients; and 2) The incidence of postoperative complications is very high, with the main complication rate of 12%-52%. The common complications are intestinal obstruction, abscess, hematologic toxicity, fistula, and septicemia [55].

Isolated retroperitoneal lymph node metastases usually recur after radical resection of CRC, accounting for about 1% of all CRC patients. After retroperitoneal lymphadenectomy, the median survival time is 31 months, with an overall five-year survival rate of 15%, compared with the median survival time of 3 months in the unresected patients [56]. However, the retroperitoneal lymphadenectomy is only limited to some cases. It is not appropriate when the metastases invade major blood vessels (such as superior mesenteric artery, abdominal axis, and aorta) and organs (such as the pancreas, bile ducts, and duodenum) or in patients intolerant to surgery.

Radiotherapy

The radiotherapy for the treatment of mCRC includes traditional radiotherapy and stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT). Traditional radiotherapy has a limited effect in extracranial malignant tumors due to natural body movement and low radiation tolerance by the normal surrounding tissue. Consequently, traditional radiotherapy is only used for local symptom relief as a palliative treatment. SBRT, on the other hand, can be used for the local treatment of patients with oligometastatic CRC to achieve a tumor-free status [17]. SBRT along with the use of low-fraction radiation can deliver high-dose radiation to the target area, while normal tissues receive only low doses of radiation. In addition, the high dose radiation from SBRT provides additional anti-tumor effects, including direct cytotoxicity and microvascular damage in the target tumor tissue [18].

SBRT can be used for inoperable patients with oligometastatic CRC. In 2014, it was reported, the 2-year local control rate after SBRT against liver metastases is about 80%, and the 2-year survival rate was 32%-83%. The 2-year local control rate after SBRT against lung metastases was about 80% and the 2-year overall survival rate was 33%-86%. As for retroperitoneal lymph node metastases, the overall 3-year survival rate of patients with SBRT treatment was reported at 71% [18]. SBRT was reported to cause some complications including radioactive hepatitis, pneumonia, and enteritis. Currently, the efficacy study of SBRT to treat mCRC is limited to a small sample size. The optimum dose, indication, and validity of SBRT are still to be defined.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy can be applied as extensive mCRC palliative care, as well as conversion therapy for potentially resectable mCRC and adjuvant therapy for resectable mCRC. First-line chemotherapy can increase the median overall survival of patients with extensive mCRC to 12-20 months [19-22]. To date, the main CRC chemotherapy regimens include: FOLFIRI (calcium folinate, fluorouracil and irinotecan) [19]; FOLFOX (calcium folinate, fluorouracil and oxaliplatin) [20]; CapeOX (capecitabine and oxaliplatin) [21]; FOLFOXIRI (calcium folinate, fluorouracil, irinotecan and oxaliplatin) [22].

Chemotherapy is also used as a conversion therapy for unresectable mCRC and an adjuvant therapy for resectable mCRC. Conversion therapy can be used to improve disease status of unresectable metastases, and transform them into resectable lesions [57,58]. A report showed that 10% to 30% of patients with unresectable liver metastases became resectable after chemotherapy [59]. As for resectable mCRC, preoperative neoadjuvant chemotherapy is used to help determine the tumor response to chemotherapy. Thus, it also determines the optimal postoperative chemotherapy regimen. Preoperative neoadjuvant chemotherapy was also able to aid in identifying the patients not suitable for surgery due to the particular invasiveness of the tumor [60]. In addition, it has been shown that adjuvant chemotherapy after surgery for resectable mCRC improves the prognosis, where the 5-year RFS and OS rates (27% and 67%, respectively) of the patients receiving adjuvant chemotherapy are higher compared to those of the patients not receiving adjuvant chemotherapy after surgery (14% and 46%, respectively) [61].

Due to the poor selectivity of chemotherapeutic drugs used, treatments often come with serious systemic side effects. In patients, FOLFIRI has been shown to often cause mucous membrane inflammation, nausea, vomiting, and hair loss, while FOLFOX often causes neutropenia and neurosensory toxicity [62]. In addition, chemotherapy is not effective to treat all mCRC after surgery. Previous studies showed the use of chemotherapy after removal of peritoneal metastases did not result in obvious improvement in prognosis, and its overall survival rate was significantly lower than that of other organ metastases [63,64]. The main reason was that the concentration of intravenous chemotherapy drugs can be diluted significantly after penetrating through the peritoneal-plasma barrier, which meant the effective drug concentration in the peritoneal cavity cannot be achieved [65].

Interventional therapy

Interventional therapy of mCRC mainly includes ablation of energy devices (radiofrequency ablation, cryoablation, microwave ablation), embolization of interventional (chemotherapy or radiotherapy drugs), and local application of chemical drugs [43,66]. The treatment of hepatic metastasis of CRC remains the most common and important point in mCRC therapy, and surgery is the preferred treatment. A 10-year (1992-2002) clinical study enrolled 418 patients with CLM, assigned different treatment to them, and found that the total recurrence rate of ablation alone group was significantly higher than that of surgery combined with ablation group and surgery alone group for colorectal cancer with liver metastasis (84% vs 64% vs 52%) [67]. After follow-up for 4 years, the overall survival rate was 22% in the ablation alone group, 36% in the surgical combined ablation group, and 65% in the surgery alone group. The overall survival rate in the 5-year follow-up group was still 58% [67]. However, there are still a large number of patients with CLM who cannot remove the lesion completely. Therefore, the use of interventional therapy (such as ablation, interventional embolization, and local injection of chemicals) is of great significance for eliminating tumor lesions and improving PFS and OS in CLM patients. A phase II clinical trial (EORTC 40004) enrolled 119 patients with mCRC that cannot be resected completely, through comparing the efficacy of radiofrequency ablation + systemic chemotherapy and systemic chemotherapy, concluded that radiofrequency ablation combined with chemotherapy than simple chemotherapy significantly improves the OS and PFS. To radiofrequency ablation combined with systemic chemotherapy, the 3-year survival rate was 27.6%, the median progression-free survival was 16.8 months, and to systemic chemotherapy group, the 3-year survival rate was 10.6%, the median survival was 9.9 months [68]. In the latest guidelines of the European cancer society (ESMO), the significance of ablative therapy in the treatment of oligometastatic mCRC is again emphasized. The treatment of oligometastatic mCRC needs to be determined based on multidisciplinary discussions. Treatment options include R0 surgical resection, radiofrequency ablation, and interventional embolization [32].

Biotherapy

In recent years, the application of biotherapy in the treatment of cancer is a growing interest in cancer research. The main biotherapeutic agents used against mCRC include targeting drugs for CRC biomarkers and immunosuppressants for immune checkpoints [29-31]. However, biotherapy alone improves patients’ survival time limitedly, therefore, it’s usually used in combination with chemotherapy [69,70]. Along with chemotherapy, biotherapy was often used as palliative therapy for extensive mCRC and conversion therapy or adjuvant therapy in resectable mCRC [60,71].

Targeting biotherapy drugs used for mCRC treatment include monoclonal antibody for epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) [23-28]. EGFR targeting drugs include cetuximab (EGFR monoclonal antibody) and paracetamol. The overall survival time of patients with K-ras wildtype mCRC treated with cetuximab was 9.5 months, which almost doubled compared to 4.8 months for patients with supportive care alone [28]. In addition, cetuximab in combination with chemotherapy regimens such as FOLFOX and FOLFIRI reduced the risk of progression in K-ras wild type mCRC patients [44,45]. Unfortunately, cetuximab can only use for wild-type K-ras patients, since it was shown to not be beneficial in treating K-ras mutant patients [28,44].

VEGF targeted monoclonal antibody includes bevacizumab. Several studies have shown that the combination of bevacizumab and chemotherapy regimens prolongs the survival of patients with mCRC [23-25]. However, a study in 2015 found that the VEGF monoclonal antibody combined with the current first-line chemotherapy regimen of FOLFIRI and FOLFOX did not increase progression-free survival and the overall survival in patients with mCRC [23]. Thus, the efficacy of such therapies is still controversial.

The prevailing immunity inhibitors of programmed cell death protein-1 (PD-1) and Cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated protein-4 (CTLA-4) are effective in the treatment of mismatch repair deficient/microsatellite instability-high (dMMR/MSI-H) CRC [29,30]. Patients with mCRC of dMMR/MSI-H are usually not sensitive to chemotherapy, but they will experience a long-term control of the disease after receiving a combination of naloxone (a PD-1 inhibitor) and chemotherapy [31]. Compared with PD-1 inhibitor monotherapy alone, the combination of naltrexone and ipilimumab (a CTLA-4 inhibitor) improves the efficacy in mCRC of dMMR/MSI-H patients with higher progression-free survival and overall survival [30]. However, the application of immunity inhibitors has its limitations. First, the incidence of dMMR/MSI-H in the CRC terminal stage was low (about 3%-5%) [72], while whether or not to take immunity inhibitors depends on the type of tumor. Second, the efficacy of PD-1 inhibitors in patients with mismatch repair proficient/microsatellite instability-low (pMMR/MSI-L) or normal mismatch repair proficient/microsatellite stability (pMMR/MSS) was poor [29]. In addition, the combination therapy of PD-1 inhibitor and CTLA-4 inhibitor was beneficial only in a small number of pMMR/MSI-L patients [30].

In summary, there are some limitations in the traditional surgical treatment of mCRC, such as surgical trauma, side effects, and drug resistance. Surgical treatment is only limited to patients with resectable metastasis [15,33,35]. This method also leads to a higher rate of postoperative recurrence or complication [52,54,73]. SBRT, on the other hand, can be used for inoperable patients with oligometastatic CRC. However, indications for radiotherapy are limited, and the optimal dose and efficacy remain unknown [17,18]. Although chemotherapy showed some effectiveness in improving the disease status of mCRC and converting an unresectable tumor in to an operative lesion, its disadvantages and limitations include poor selectivity, poor efficacy, and more systemic adverse reactions [19-22,62]. Biotherapy, a relatively new concept, is often used in combination with chemotherapy and is only limited in treating a specific set of mCRC cohort [28,44,69,70]. There are levels of trauma and often major side effects associated with the current mCRC treatments available. Therefore, it is desirable to exploit new therapeutic strategies with low trauma and fewer side effects in the treatment of mCRC.

Photothermal therapy (PTT) for CRC

Photothermal therapy is a new technology of tumor therapy with great potential. The procedure for PTT is concentrating photothermal nano-materials on the tumor tissue by targeting technology, and then illuminating the tumor tissue with a light source. In this way, the light energy from the irradiation with strong tissue penetration is rapidly converted into heat energy utilizing photothermal nanomaterials, and thus killing the tumor cells [74]. Compared to the traditional treatment methods, PTT has significant advantages including higher specificity, lower invasive injury, and less normal tissue damage [75].

Photothermal nanomaterials for PTT

Photothermal nanomaterials are nano-materials with the ability of photothermal conversion, usually using near-infrared radiation (NIR) as the light energy source [74,76]. Tissue components such as hemoglobin and water have the highest transmittance for NIR, allowing it to penetrate through 10 cm of subcutaneous tissue, 4 cm of skull/brain tissue, or 4 cm of muscle tissue [77,78]. Under the irradiation of NIR, only the part of the photothermal nanomaterial can produce enough heat to specifically kill the cancer cells, without damaging the surrounding tissues [79]. The types of photothermal nanomaterials currently under development for the use in CRC PTT include noble metal nanomaterials, carbon-based nanomaterials, metal compounds nanomaterials and organic nanomaterials [80]. Table 2 summarizes the application, outcomes, and clinical application prospects of various PTT materials with in vitro and in vivo models.

Table 2.

Photothermotherapy for CRC (continued from previous table)

| Category | Material | Model | Wavelength and intensity | Application | Outcome | Summarize | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Noble metal nanomaterials | SN38 conjugated hyaluronic acid gold nanoparticles | HT-29 and SW-480 cells | 630 nm; 30 mW 6 min | Combined chemo-PTT | Decreased cell viability and cell migration | excited with visilbe light; PTT in vitro; Lack of in vivo application value | [81] |

| Anti-MG1 conjugated hybrid magnetic gold nanoparticles | CC-531 cells CRC liver metastasis-bearing rats | 808 nm; 0.56 W/cm2 3 min | PTT, MR imaging | Increased tumor necrosis rate | excited with NIR; PTT; low photostability | [82] | |

| Immune-targeted gold-iron oxide hybrid nanoparticles | SW-1222 cells subcutaneous tumor-bearing mice | 808 nm; 3-5 W/cm2 20 min*7 times | PTT, MR imaging | Slowing down of tumor growth, tumor tissue necrosis | excited with NIR; PTT; low photostability | [83] | |

| Gd2O3: Ln coated gold nanorods | CC-531 cells CRC liver metastasis-bearing rats | 808 nm; 0.5/0.55 W/cm2 3 min | PTT, CT imaging | Large necrotic region in the center of the tumor | excited with NIR; interventional imaging guided chemo-PTT; low photostability | [84] | |

| Methylene blue loaded gold nanorods with SiO2 shell | CT-26 cells | 780 nm; 1 W/cm2 50 min | Combined PTT-PDT | Cell activity dropped to 11% | excited with NIR; PTT; low photostability | [85] | |

| PEGylated gold nanorods | CT-26 cells subcutaneous tumor-bearing mice | 808 nm; 3.5 W/cm2 | PTT | Increased OS, 4/9 of mice completed ablation | excited with NIR; molecular targeting and magnectic targeting guided chemo-PTT; low photostability | [86] | |

| FITC/cisplatin loaded chitosan-gold nanorods | LoVo cells | 808 nm; 1/2/3 W/cm2 | chemo-PTT, fluorescence imaging | Decreased cell viability | excited with NIR; chemo-PTT; low photostability | [87] | |

| MUC-1 aptamer targeted gold coated superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles | HT-29 cells | 820 nm; 0.7 W/cm2 2 min | PTT, MR imaging | Decreased cell viability | excited with NIR; PTT; low photostability | [88] | |

| DOX-loaded gold half-shell nanoparticles with anti-DR4 antibody | DLD-1 cells subcutaneous tumor-bearing mice | 808 nm; 82 W/cm2 10 min | Combined chemo-photothermal therapy | Slowing down of tumor growth, tumor tissue necrosis | excited with NIR; molecular targeting guided chemo-PTT; reduce MDR; low photostability | [89] | |

| FePt-gold nanoparticles hybrid anisotropic nanostructures | HT-29 cells subcutaneous tumor-bearing mice | 808 nm; 0.6 W/cm2 | PTT, MR/PAI imaging | Completed ablation | excited with NIR; MRI and PAI guided chemo-PTT; cytotoxicity | [90] | |

| Assembled phage fusion proteins modifed gold-silver hybrid nanorods | SW-620 cells | 808 nm; 4 W/cm2 10 min | PTT, fluorescence imaging | Decreased cell viability | excited with NIR; PTT; photostability | [91] | |

| Carbon-based nanomaterials | Irinotecan loaded hyaluronic acid/polyaspartamide-based double-network nanogels | HCT-116 cells | 810 nm; 3×10-3 W/mm3 | chemo-PTT | Decreased cell viability | excited with NIR; chemo-PTT; low photothermal conversion efficiency; cumulative toxicity | [103] |

| SN38 conjugated cyclodextrins coated graphene oxide | HT-29 cells | 808 nm; 2 W/cm3 | chemo-PTT | Decreased cell viability | excited with NIR; chemo-PTT; low photothermal conversion efficiency; cumulative toxicity | [104] | |

| Cetuximab/DOX modified magnetic graphene oxide | CT-26 cells subcutaneous tumor-bearing mice | 808 nm; 2.5 W/cm2 | chemo-PTT, MRI guidance | Completed ablation | excited with NIR; chemo-PTT; dual targeting; low photothermal conversion efficiency; cumulative toxicity | [105] | |

| Folic acid-functionalized multi-walled carbon nanotubes | RKO and HCT-116 cells | 1,064 nm; 30 J/cm2 | PTT | Decreased cell viability | excited with NIR; chemo-PTT; enhanced tumor affinity; low photothermal conversion efficiency; cumulative toxicity | [106] | |

| Multiwalled carbon nanotubes | RKO and HCT-116 cells | 1064 nm; 3 W/cm2 10 s | chemo-PTT | Decreased cell viability | excited with NIR; chemo-PTT; enhanced photothermal conversion efficiency; cumulative toxicity | [107] | |

| POSS-PCU nanocomposite polymer | HT-29 cells | 808 nm; 1/0.5 W/cm2 10 min | PTT | Decreased cell viability | excited with NIR; chemo-PTT; enhanced biocompatibility and photothermal conversion efficiency | [108] | |

| Metal compounds nanomaterials | copper sulfate nanocomposite materials | Caco-2 cells | 808 nm; 1/2/5 W/cm2 | PTT | Decreased cell viability | excited with NIR; PTT; low photothermal conversion efficiency; cumulative toxicity; inexpensive | [115] |

| PEGylated copper nanowires | CT-26 cells subcutaneous tumor-bearing mice | 808 nm; 1.5 W/cm2 6 min | chemo-PTT | Slowing down of tumor growth, tumor tissue necrosis | excited with NIR; PTT; low photothermal conversion efficiency; cumulative toxicity; inexpensive | [116] | |

| Amphiphilic polymer coated copper selenide nanocrystals | HCT-116 cells | 800 nm; 33 W/cm2 5 min | PTT | Necrocytosis | excited with NIR; PTT; inexpensive; moderate photothermal conversion efficiency; cumulative toxicity | [117] | |

| Organic nanomaterial | EGFR targeted micelles loaded with IR-780 | HCT-116 and SW-620 cells subcutaneous tumor-bearing mice | 780 nm 1.8 W/cm2 | chemo-PTT | Completed ablation of HCT-116 tumor | excited with NIR; chemo-PTT; biocompatibility and biodegradation; multimodal images; photobleaching | [118] |

| IR780 encapsulated nanostructured lipid | CT-26 cells subcutaneous tumor-bearing mice | 808 nm; 2 W/cm2 | PTT | Slowing down of tumor growth, tumor necrosis | excited with NIR; chemo-PTT; biocompatibility and biodegradation; Oral administration; photobleaching | [119] | |

| Indocyanine green and DOX loaded hyaluronic acid | HCT-116 cells subcutaneous/in situ tumor-bearing mice | 808 nm; 1 W/cm2 | chemo-PTT | inhibition of subcutaneous tumor and in situ tumor | excited with NIR; chemo-PTT; better biocompatibility and biodegradation; controllable drug release; photobleaching | [120] | |

| Radionuclide rhenium labeled micelles containing Dye IR-780 | HCT-116 cells subcutaneous tumor-bearing mice | 808 nm; 1.8 W/cm2 | PTT, SPECT imaging | Slowing down of tumor growth, tumor tissue necrosis | excited with NIR; chemo-PTT; biocompatibility and biodegradation; tissue damage | [121] | |

| SN38 and dye IR780 loaded nanomicelles | HCT-116 cells subcutaneous tumor-bearing mice | 808 nm; 1 W/cm2 | chemo-PTT | Slowing down of tumor growth, tumor tissue necrosis | excited with NIR; chemo-PTT; biocompatibility and biodegradation; reticuloendothelial system avoidance | [122] | |

| ADS-780 decorated apoferritin nanoparticles | HT-29 cells subcutaneous tumor-bearing mice | 808 nm; 1.2 W/cm2 | chemo-PTT fluorescence imaging | Slowing down of tumor growth, tumor tissue necrosis | excited with NIR; chemo-PTT; biocompatibility and biodegradation; dual-release mechanisms | [123] | |

| Platinum-chelated bilirubin nanoparticles | HT-29 cells subcutaneous tumor-bearing mice | 808 nm; 1 W/cm2 | PTT, PAI imaging | Slowing down of tumorgrowth, tumor tissue necrosis | excited with NIR; chemo-PTT; biocompatibility and biodegradation; PAI; EPR | [135] | |

| SN-38-encapsulated nanoporphyrin micelles | HT-29 cells subcutaneous tumor-bearing mice | 690 nm; 45/90 J/cm2 | chemo-PTT-PDT | Slowing down of tumorgrowth, tumor tissue necrosis | excited with NIR; chemo-PTT-PDT; biocompatibility and biodegradation; multimodal images | [124] | |

| Diketopyrrolopyrrole-triphenylamine organic Nanoparticles | HCT-116 cells subcutaneous tumor-bearing mice | 660 nm; 1 W/cm2 | PTT and PDT, PAI imaging | Completed ablation | excited with NIR; imaging combined with chemo-PTT; better biocompatibility and biodegradation; EPR; PTT-PDT | [125] | |

| Organic nanomaterial | Fe3+/vinylpyrrolidone coordination polymer nanoparticles | SW-620 cells subcutaneous tumor-bearing mice | 808 nm; 1.3 W/cm2 6 min | PTT,MR imaging | Completed ablation | excited with NIR; MRI guided PTT; biocompatibility and biodegradation; tumour-imaging sensitivity; facilitated renal clearance | [127] |

| Polydioxanone nanofibers | CT-26 cells | 808 nm; 2 W/cm2 3 min | chemo-PTT | Decreased cell viability | excited with NIR; chemo-PTT; biocompatibility and biodegradation; multimodal images | [126] | |

| Polyaniline-coated upconversion nanoparticles | U87MG cells subcutaneous tumor-bearing mice | 808 nm; 0.5 W/cm2 | PTT, fluorescence imaging | Completed ablation | excited with NIR; chemo-PTT; better biocompatibility and biodegradation;multimodal images | [128] | |

| Polyoxyethylene chain coated polyaniline nanoparticles | HCT-116 cells subcutaneous tumor-bearing mice | 808 nm; 0.5 W/cm2 | PTT | Completed ablation | excited with NIR; chemo-PTT; biocompatibility and biodegradation; photobleaching | [129] | |

| Conjugated polymer PCPDTBSe nanoparticles | CT-26 cells | 450/800 nm; 1.91/3.82 W/cm2 | PTT | Decreased cell viability | excited with NIR; chemo-PTT; biocompatibility and biodegradation; multimodal images; photobleaching | [130] | |

| Low band gap donor-acceptor conjugated polymer nanoparticles | RKO and HCT-116 cells | 808 nm; 600 mW/cm2 | PTT | Decreased cell viability | excited with NIR; chemo-PTT; biocompatibility and biodegradation; photobleaching; high photothermal effciency | [131] |

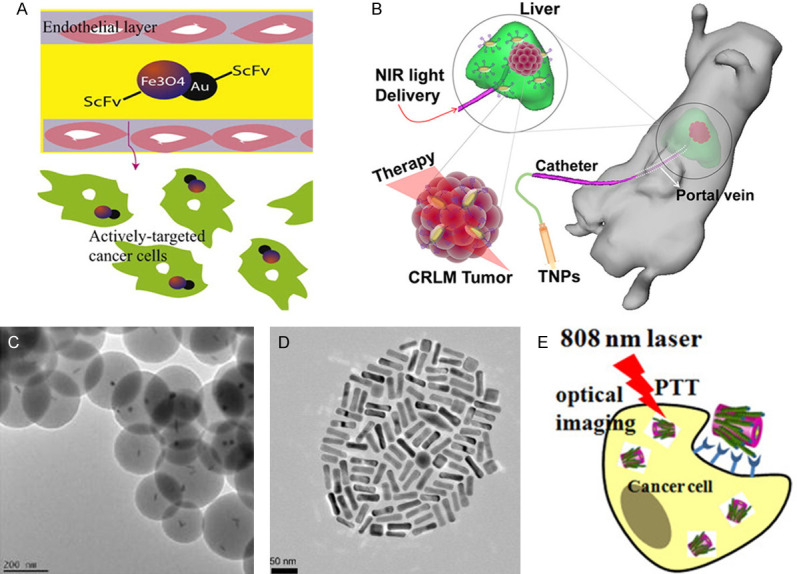

The noble metal nanomaterials of photothermal nanomaterials for photothermal therapy include gold nanoparticles [81-84], gold nanorods [85-87], gold nanoshells [88,89], and silver-based or platinum-based nanomaterials [90,91]. The surface plasmon resonance (SPR) of noble metal nanomaterials is the basis of their photothermal conversion ability [92], The absorption wavelength and photothermal conversion efficiency of these nanomaterials depend on the SPR effects, adjusted by the size, shape and structure of these nanomaterials [93].

The absorption peak of spherical gold nanoparticles is located within the visible light range. In 2017, Hosseinzadeh et al. demonstrated the use of a gold nanoparticle targeting MUC1 aptamer, with the maximum absorption wavelength of 630 nm which is within visible wavelength range in vitro [81]. Although they demonstrated its ability in decreasing the activity and migration of colorectal cancer cells by photothermal effect, the pure gold spherical nanoparticles alone were unsuitable for in vivo work due to the absorption peak of visible radiation. Therefore, the gold nanoparticles need to be hybridized to other materials, which will adjust their absorption peak to the near-infrared region making it suitable for PTT [94]. This is demonstrated in a paper showing tail vein injection of a gold-iron oxide hybrid nanoparticle targeting the CRC single-chain antibody A33scFv into the CRC subcutaneous tumor-bearing mice slowed down the growth rate of tumor volume and caused necrosis of tumor tissue after irradiation with NIR (Figure 1A) [83]. In addition, the material can be used as a contrast agent for T2-weighted imaging in magnetic resonance (MR) imaging, which can clearly show antigen-expressing tumor cells in vivo [83].

Figure 1.

Noble metal nanomaterials. A. Gold-iron oxide hybrid nanoparticles [83]; B. Portal vein injection of Au@Gd2O3:Ln [84]; C. Methylene blue loaded gold nanorods with SiO2 shell [85]; D. PEGylated gold nanorods [86]; E. schematic diagram showing PHNRS for PTT against CRC SW-620 cells [91].

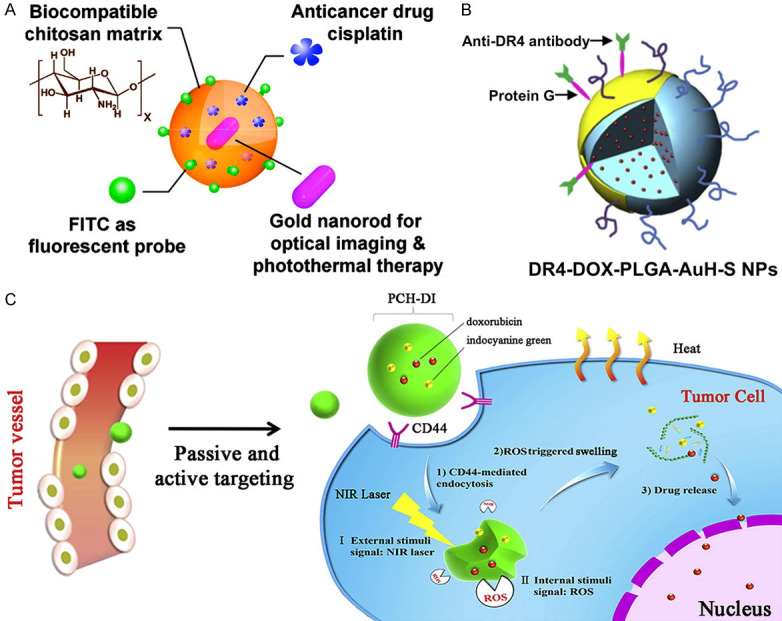

The absorption peak of gold nanorods is suitable to be adjusted to the NIR region by adjusting the aspect ratio [95]. Similarly, the method for adjusting the gold nanoshells is adjusting the size and the thickness [96]. In recent years, there are several studies indicating the potential of nanorod as a tool for PTT against CRC. This is demonstrated in a paper by Parchur et al., where they synthesized gold nanorods coated with Gd2O3: Ln (Au@Gd2O3: Ln) [84]. Their results showed that the nanorod injected through the portal vein into CRC liver metastatic cancer-bearing rats (Figure 1B) were able to cause tumor tissue necrosis by NIR irradiation, with minimal damage to the normal surrounding liver tissue. Another group showed a PEGylated gold nanorod intravenous injected and activated by NIR irradiation increased the average survival time of the CRC subcutaneous tumor-bearing mice significantly (Figure 1D) [86]. As a result, 4/9 of the mice had complete tumor ablation. In addition, a number of in vitro experiments also support the anti-tumor effect of the nanorod. Methylene blue loaded gold nanorods with SiO2 shell (Figure 1C) was shown to decrease the activity of CRC cells to 11% after NIR irradiation [85], while FITC and cisplatin loaded chitosan-gold nanorods hybrid nanosphere was also effective in decreasing CRC cell viability [87]. Gold nanoshells have a characteristic of the ability to carry functionalized molecules, thus making it multifunctional. This is shown in the paper describing the simultaneous use of a gold nanoshell carrying superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles in PTT and MR imaging [88]. Moreover, gold half-shell nanoparticles loaded with a chemotherapeutic drug doxorubicin (DOX) could produce both chemotherapy and PTT effects in CRC subcutaneous tumor-bearing mice [89]. Low photostability is the common disadvantage of gold materials. Low photostability can cause structural deformation, and structure deformation is one of the disadvantages in the use of gold materials [97]. This makes the viability and the therapeutic effects of gold materials difficult to control for treatments that require long irradiation time. Further study is required in creating a stable nanomaterial.

Platinum-based and silver-based nanomaterials are also considered for photothermal therapy. PVIII fusion protein modified gold-silver hybrid nanorods (PHNRS, Figure 1E) were used in PTT to target against CRC cells. As a result, the cell viability of cancer cells was reduced to 30%, while the control group was above 80% [91]. In addition, FePt-gold hybrid nanoparticles were put into the CRC subcutaneous tumor mouse model by intra-tumor injection, causing complete tumor ablation after NIR irradiation [90]. Besides their photothermal conversion properties, platinum nanomaterials have natural anticancer properties including their ability in causing DNA strand breaks and their antioxidant behavior [98,99], which could be enhanced by appropriate surface modification [100]. The anticancer characteristic of silver nanoparticles is the release of Ag+ that results in the formation of reactive oxygen species, and further mitochondrial toxicity and DNA damage [100,101]. Therefore, the cytotoxicity produced by local high concentrations of platinum-based and silver-based nanoparticles form a synergistic effect with photothermal therapy. Unfortunately, both platinum-based and silver-based nanomaterials have disadvantages in causing cytotoxicity to normal cells as well. For platinum-based nanomaterials, the reason is that their ability to cause DNA strand breaks in cells is non-selective, while for silver-based nanomaterials the reason is that they can also be easily oxidized by O2 or H2S in vivo to produce cytotoxic Ag+ in surrounding tissue or in blood circulation [102].

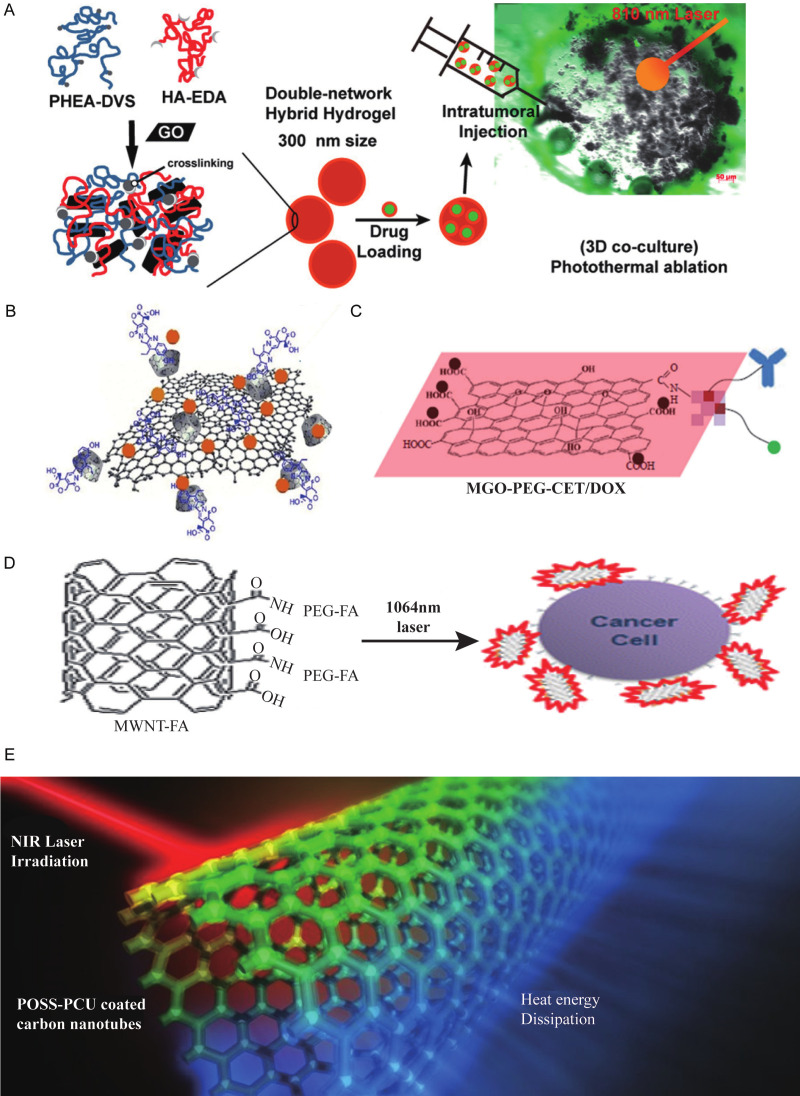

Carbon-based nanomaterials also have NIR absorption capacity. The types which currently under development for photothermal therapy include graphene [103-105] and carbon nanotubes [106-108]. Graphene is made up of a flat sheet of carbon atoms, while carbon nanotube is a three-dimensional structure made of graphene [109,110].

Carbon-based nanomaterials have electrochemical properties and non-covalent bond binding properties, thus allowing them to use in combination with functionalized molecules which also have covalent or noncovalent binding and different surface chemical properties. Some of these include magnetic materials [105] and chemotherapeutic drugs [111]. A number of publications have demonstrated due to the large aromatic surface areas of the graphene oxide nanogels, they can be loaded with chemotherapeutic drugs including irinotecan (Figure 2A) [103], SN38 (an active metabolite of irinotecan, Figure 2B) [104], cetuximab and Fe3O4 magnetic nanoparticles (Figure 2C) [105]. In addition, another paper showed that the multiwalled carbon nanotubes bound with folic acid Figure 2D) can enhance the affinity for CRC cells by 400-500%, and decrease the activity of CRC cells by 50-60% after NIR irradiation [106]. Moreover, Tan et al., synthesized poly (carbonate-urea) urethane functionalized multiwalled carbon nanotubes (POSS-PCU, Figure 2E) that can thermally ablate cancer cells under NIR irradiation [108]. However, the main disadvantages of carbon-based nanomaterials are first their low photothermal conversion efficiency, which means a higher irradiation wavelength or intensity is necessary compared with other materials. This may result in more normal tissue damage [112]. Second, they can easily deposit into organs such as liver, kidney, and skin, causing granuloma formation and further leading to the development of cysts and organ damage [113,114].

Figure 2.

Carbon-based nanomaterials. A. Irinotecan loaded graphene oxide nanogels [103]. B. SN38 loaded graphene oxide nanogels [104]. C. Cetuximab and Fe3O4 Magnetic nanoparticles loaded graphene oxide nanogels [105]. D. Multiwalled carbon nanotubes bound with folic acid [106]. E. POSS-PCU nanocomposite polymer [108].

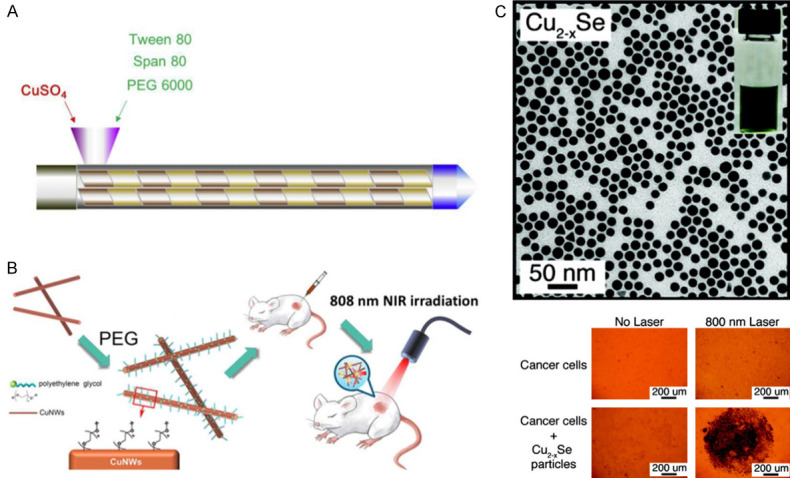

Currently, the studies of metal compound nanomaterials used in CRC photothermotherapy are few, and the materials targeting CRC in vivo need to be developed. Metal compound nanomaterials mainly include copper compounds [115-117]. The advantages of metal compound nanomaterials are their low cost and low cytotoxicity [116]. A recent study reported that copper sulfate nanocomposite materials (CuSO4 NCs, Figure 3A) decreased the viability of CRC cells after NIR irradiation [115]. In addition, polyethylene glycol coated copper nanowires (PEGylated CuNWs, Figure 3B) was shown to induce tumor cell necrosis and inhibit tumor growth in CRC subcutaneous tumor-bearing mice through intratumor injection and NIR irradiation [116]. Furthermore, Hessel et al. [117] synthesized copper selenide nanocrystals (Cu (2-x) Se nanocrystals, Figure 3C) that necrotized CRC cells under NIR irradiation. The disadvantage of metal compound nanomaterials is similar to carbon-based nanomaterials in that they also have low photothermal conversion efficiency. Ultimately, these materials require high power NIR or adjustment in their size and shape to improve the photothermal conversion ability [75].

Figure 3.

Metal compounds nanomaterials. A. CuSO4 NCs [115]. B. PEGylated CuNWs [116]. C. Cu (2-x) Se nanocrystals [117].

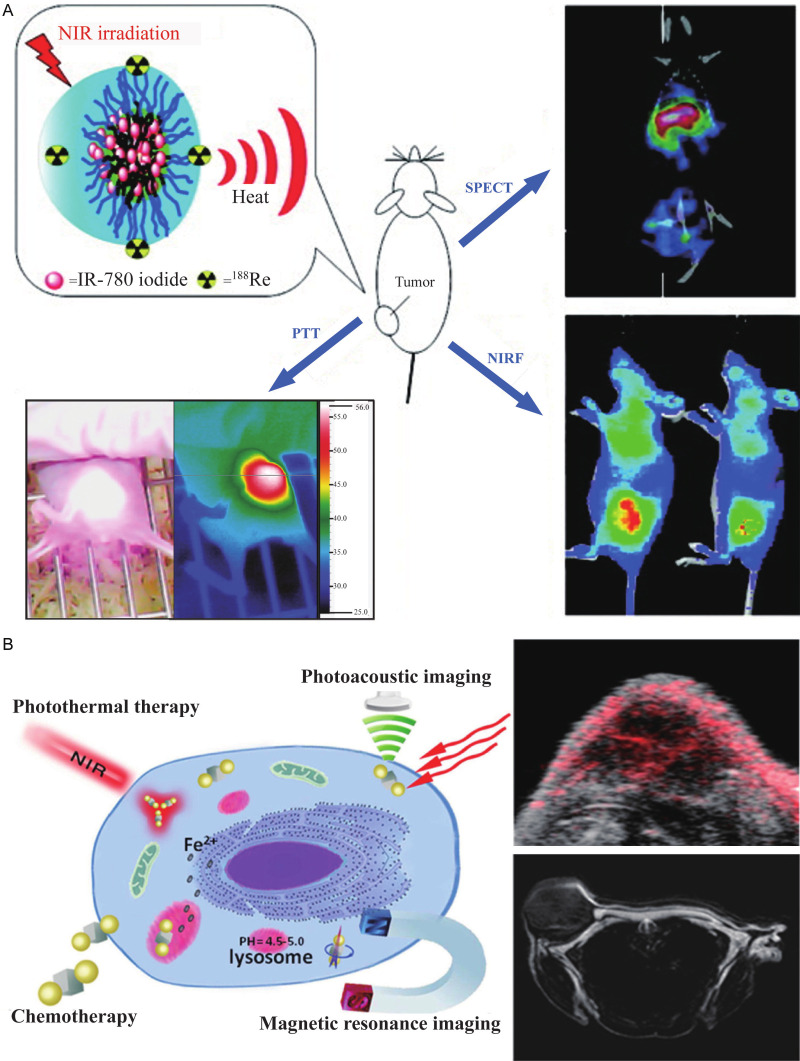

Organic nanomaterials currently under development include NIR dye-based nanomicelles [118-124], porphyrin liposome nanomaterials [89], small organic nanomaterials [125]; and organic polymer nanomaterials [126-131].

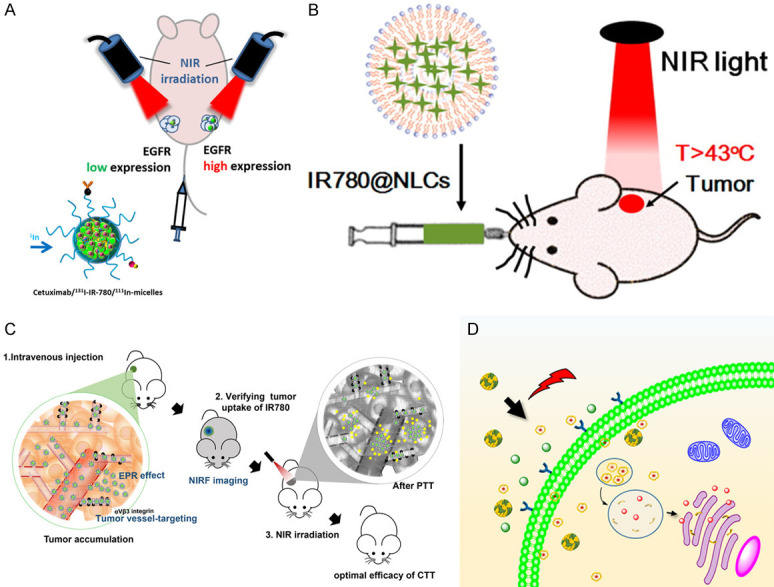

Organic nanomaterials have better biocompatibility and biodegradation compared with inorganic nanomaterials [132]. This is demonstrated a by research showing the use of nanomaterials containing NIR dyes such as indocyanine green and heptamethine cyanine which can be excreted through the urine [133]. Nanomaterials carrying liposome and protein have been shown to be degraded in the body [134,135]. It was shown that an EGFR-targeted micelle containing NIR dye IR-780 (Figure 4A) can successfully accumulate in CRC tumor tissue through tail vein injection of subcutaneous tumor-bearing mice and subsequently reduce the size of the tumor after irradiation [118]. In another report, they demonstrated that a nanostructured lipid carrier containing NIR dye (IR780@NLCs, Figure 4B) was stable in simulated gastric and intestinal conditions and targeted tumor in subcutaneous tumor-bearing mice through oral absorption [119]. In addition, some polymer materials, such as Fe3+/vinylpyrrolidone coordination polymer nanoparticles [127], polyaniline-coated upconversion nanoparticles [128], and polyoxyethylene chain coated polyaniline nanoparticles [129], have been shown to completely ablate the tumor in a CRC subcutaneous tumor-bearing mouse model after NIR irradiation.

Figure 4.

Organic nanomaterials. A. EGFR-targeted micelles containing NIR dye [118]. B. IR780@NLCs [119]. C. SN38 and dye IR780 loaded nanomicelles [122]. D. Dye ADS-780 decorated apoferritin nanoparticles [123].

For combined applications, some organic nanomaterials have been designed to bind to functional molecules, such as anticancer drugs and contrast agents. Many functional molecules binding nanomaterials for colorectal cancer were reported, including SN38 and dye IR780 loaded nanomicelles (Figure 4C) [122], SN-38-encapsulated nano porphyrin micelles (SN-NPM) [122], DOX and indocyanine green loaded hyaluronic acid [120], dye ADS-780 decorated apoferritin nanoparticles (Figure 4D) [123], Platinum-chelated bilirubin nanoparticles [136], and radionuclide rhenium labeled micelles containing Dye IR-780 [121]. After tail vein injection and NIR irradiation of these materials in CRC subcutaneous tumor-bearing mice they were all shown to be effective in slowing down the growth rate of tumor volume and in causing tumor tissue necrosis. The disadvantage of organic photothermic agents is their susceptibility to photobleaching [118]. Their absorption capacity decreases rapidly as functions of time, which makes them insufficient for long irradiation treatment [135].

Combined application of photothermal therapy

Imaging-guided photothermal therapy is an effective method to detect the biological distribution of photothermal nanomaterials and evaluate the performance of PTT in tumor ablation. In this way, visualization of the tumor metastasis provides an effective reference factor for irradiation range before treatment, and therapeutic effect after treatment as well. These include fluorescence imaging [87,91,123,128], MR imaging [82-84,88,90,127], and photoacoustic imaging [90,125,136].

Attaching fluorescent probes to nanomaterials is to detect/track fluorescence imaging-guided photothermal therapy. Synthesized cisplatin was loaded into chitosan/gold nanorod hybrid nanosphere conjugated to a fluorescence probe, fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) by a covalent linkage [87]. By using the microscopic scattering dark-field imaging of localized surface plasmon resonance and fluorescence images of FITC, the hybrid nanosphere could be used as a bimodal contrast agent for real-time optical imaging. At the same time, the combined effect from the PTT and chemotherapy can accelerate the death of cancer cells, allowing an all-in-one system of cell imaging, drug delivery, and photothermal therapy.

Photothermal conversion materials connected with superparamagnetic materials are suitable for MR imaging and PTT. Azhdazadeh et al. [88]synthesized gold-plated superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles with the MUC-1 aptamer as a targeting agent (Au@SPIONs). Au@SPIONs significantly attenuated the MR signal strength of CRC cells HT-29 treated compared with control cells.

Nanomaterials carrying radionuclides are applicable for positron emission tomography (PET) or single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) [137,138]. Peng et al. [121] synthesized NIR dye IR-780 loaded multifunctional micelles labeled with the radionuclide rhenium-188 for photothermal treatment and SPECT imaging in CRC subcutaneous tumor-bearing mice. The radiation of the subcutaneous tumor increased in SPECT/CT image after injection of the micelles 24 h later, achieving a better tumor and non-tumor contrast (Figure 5A).

Figure 5.

Image-guided photothermal therapy. A. NIR dye IR-780 loaded multifunctional micelles labeled with the radionuclide rhenium-188 [121]. B. hybrid anisotropic nanoparticles composed of iron platinum alloy nanoparticles and gold nanoparticles [90].

Photothermal therapy can be guided by photoacoustic imaging (PAI). Tissue produces sound waves under irradiation because of local heating and small expansion, and the signal of the photoacoustic effect is proportional to light absorption [139]. An interesting report by Zhang et al. [90] synthesized hybrid anisotropic nanoparticles (HANs) composed of iron platinum alloy nanoparticles and gold nanoparticles. The irradiation absorption ability of the gold nanoparticles was applicable as a contrast agent for PAI and as a photothermal conversion material. Also, the iron platinum alloy nanoparticles have super paramagnetism which is applicable as an MRI contrast agent [140]. Therefore, HANs can be used to act as a PAI and an MRI contrast agent, as well as a PTT photothermal conversion material, to utilize different imaging modes and overcome the disadvantages of different imaging modes. The photoacoustic signal and MR signal could be clearly detected in the tumor site 1 h after injecting HANs in tumor-bearing mice (Figure 5B).

Traditional chemotherapeutic drugs often cause systemic adverse reactions due to their poor selectivity [62]. However, combined chemo-photothermal therapy is more than just a simple combination. Here are the advantages: 1) The photothermal conversion materials are suitable as carriers of chemotherapeutic drugs, improving the selectivity of the chemotherapeutic drugs and prolonging their circulation time in the blood [141]. 2) The thermal effect produced by photothermal therapy can enhance the local chemotherapy effect [142] or allow a temperature-sensitive drug delivery system [143]. Therefore, combined chemo-PTT will allow fewer drugs to be used to achieve the same effect and thus minimize the side effects.

Recently, a publication reported a FITC/cisplatin loaded chitosan/gold nanorod hybrid nanosphere for combined chemo-PTT (Figure 6A) [87]. The idea is that the hybrid nanospheres can provide space for loading of the specific anticancer drugs, and cisplatin. Traditional cancer chemotherapy is often limited by multidrug resistance (MDR), because the multidrug resistance membrane transporters can transport multiple drugs out of cells and prevent intracellular drug accumulation [144]. However, this nanosphere technology including DOX loaded gold half-shell nanoparticles (Figure 6B) is capable of overcoming MDR by transferring heat to cancer cells effectively [89]. As a result, the nanoparticles combined with the chemotherapy drugs decreased the growth rate of tumors in a CRC subcutaneous tumor-bearing mouse model with a significantly lower DOX dose compared to conventional chemotherapy at a higher dose. Another group showed treatment of hyaluronic acid nanoparticles loaded with DOX and indocyanine green (PCH-DI, Figure 6C) [120] can result in 82.9% subcutaneous tumor inhibition. PCH-DI treatment in the in-situ induction model resulted in a significantly lower number and volume of tumors compared to those in the chemotherapy alone group, PTT alone group, or untreated group.

Figure 6.

Combined chemo-photothermal therapy. A. FITC/cisplatin loaded chitosan/gold nanorod hybrid nanospheres [87]; B. DOX loaded gold half-shell nanoparticles [89]. C. PCH-DI [120].

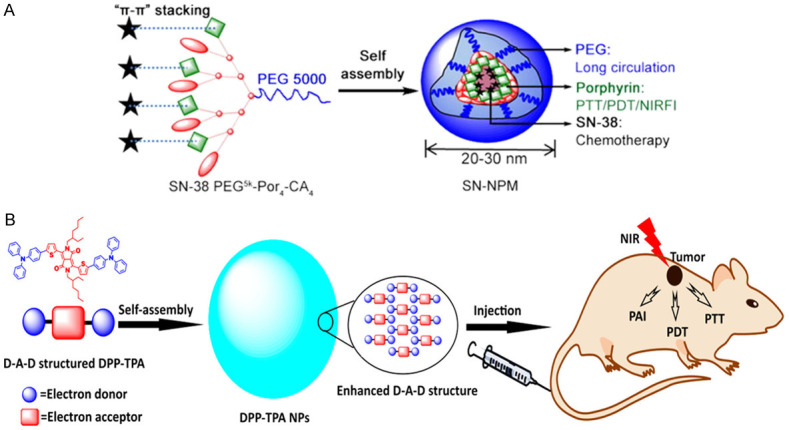

Photosensitizers used in photodynamic therapy (PDT) transport energy to oxygen molecule to produce cytotoxic singlet oxygen and subsequently induces cells to produce cytokines which can destroy tumor cell membranes and microvessels [145,146]. Since both PDT and PTT require light irradiation, combining both photothermal-photodynamic therapies will form a highly effective cancer irradiation treatment. However, the disadvantages of PDT therapy are that the wavelength of radiation required for photosensitizer is usually less than 700 nm which is below the NIR range, and that the synthesis of water-soluble photosensitizers is difficult due to the hydrophobic structure of photosensitizers [147]. Therefore, photothermal materials are required to serve as carriers of the photosensitizers for targeted transport to the tumor regions and to address their limitations in wavelength of light irradiation and water solubility.

Recently, Seo et al. [85] used gold nanorods (GNR) combined with methylene blue (MB) as the photothermal material. Methylene blue is a water-soluble phenothiazine photosensitizer with a high quantum yield of singlet oxygen [148]. MB-GNR resulted in prolonged NIR irradiation time, thus reactive oxygen species increased significantly compared to the group with MB without the GNR photothermal material. Consequently, MB-GNR showed the dual effects of photodynamic and photothermal treatment with a significantly better anticancer effect compared to pure gold nanorod or pure methylene blue alone.

Besides, Yang et al. [124] synthesized SN-38-encapsulated nanoporphyrin micelles (SN-NPM) which were capable of combining photothermal therapy, photodynamic therapy, and chemotherapy into one (Figure 7A). SN-38 is an important and highly effective chemotherapeutic drug for various cancers including colorectal cancer [149]. Water-soluble nano porphyrin micelles can be activated to generate heat and reactive oxygen at the tumor sites under NIR irradiation. Yang et al. [124] showed the tumor volume grew significantly slower after SN-NPM combined therapy in tumor-bearing mice compared to each of the three single therapies.

Figure 7.

Combined photothermal-photodynamic therapy. A. SN-NPM capable of triple therapy of photothermal therapy, photodynamic therapy and chemotherapy [124]. B. DPP-TPA applicable for PAI-guided combined photothermal-photodynamic therapy [125].

Furthermore, Cai et al. [125] synthesized diketopyrrolopyrrole-triphenylamine organic nanoparticles (DPP-TPA) applicable for PAI combined with PTT and PDT (Figure 7B). The use of DPP-TPA showed a passive targeted effect at the tumor sites through the enhanced permeability and retention effects after they were injected into subcutaneous tumor-bearing mice [150]. In the study, the photoacoustic signal intensity reached its maximum value in the tumor site 2 hours after injection, suggesting the best waiting time for tumor localization and photothermal-photodynamic therapy. Ultimately, the tumor achieved completed ablation after the treatment.

Conclusions and perspective

In summary, the traditional treatments of mCRC, including surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and biotherapy, have inevitable limitations. Photothermal therapy provides a new strategy for the treatment of mCRC. Current researches of PTT are centered on material construction and verification on animal models, focusing on three main themes: low cytotoxicity, high photothermal conversion efficiency, and high biocompatibility.

The major challenges now remain to solve the application of photothermal therapy in clinical medicine. The first is the issue of biological safety. The photothermal nanomaterials in current researches do not cause acute toxicity in the short term, but lack of long-term toxicity evaluation criteria and research reports. The second is clinical technology issues. Current researches are limited to the treatment of cell level and animal tumor models. The corresponding medical equipment and method for clinical photothermal therapy thus are needed to investigate due to the limited range of effects of light irradiation.

Therefore, future studies need to focus on three aspects. Firstly, the evaluation standard of the biosafety of photothermal nanomaterials should be defined. In which the mechanism and rate of removal of photothermal nanomaterials, such as through their own metabolic degradation, photodegradation, or through urine excretion, need to be explored. Moreover, researchers should explore the short-term and long-term toxic and side effects caused by material deposition in vivo and define the evaluation indicators. Finally, the development of new nanomaterials or optimization of existing nanomaterials should be devoted to. The existing nanomaterials are, more or less, defective. It’s of great significance to improve the photostability of gold nanomaterials or improve the photothermal conversion efficiency of graphene nanomaterials. In another way, we could develop new nanomaterials that are photostable and efficient in photothermal conversion. What’s more, the clinical application of photothermal therapy should be studied. As to mCRC, it’s critical to explore the application of photothermal therapy for mCRC, such as external irradiation, natural intracavitary irradiation, or intraperitoneal irradiation. There is potential for photothermal therapy to become an ideal choice in accurate positioning and precise treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer with the development of interdisciplinary research.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (16ykjc25), Sun Yat-Sen University Clinical Research 5010 Program (2016005), Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Grant (1158402) and National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) (81671928).

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:394–424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel RL, Fedewa SA, Anderson WF, Miller KD, Ma J, Rosenberg PS, Jemal A. Colorectal cancer incidence patterns in the united states, 1974-2013. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2017;109 doi: 10.1093/jnci/djw322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kuipers EJ, Grady WM, Lieberman D, Seufferlein T, Sung JJ, Boelens PG, van de Velde CJ, Watanabe T. Colorectal cancer. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2015;1:15065. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2015.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Austin H, Henley SJ, King J, Richardson LC, Eheman C. Changes in colorectal cancer incidence rates in young and older adults in the United States: what does it tell us about screening. Cancer Causes Control. 2014;25:191–201. doi: 10.1007/s10552-013-0321-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moore KJ, Sussman DA, Koru-Sengul T. Age-specific risk factors for advanced stage colorectal cancer, 1981-2013. Prev Chronic Dis. 2018;15:E106. doi: 10.5888/pcd15.170274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fedewa SA, Ahnen DJ, Meester RGS, Barzi A, Jemal A. Colorectal cancer statistics, 2017. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67:177–193. doi: 10.3322/caac.21395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lemmens VE, Klaver YL, Verwaal VJ, Rutten HJ, Coebergh JW, de Hingh IH. Predictors and survival of synchronous peritoneal carcinomatosis of colorectal origin: a population-based study. Int J Cancer. 2011;128:2717–2725. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vatandoust S, Price TJ, Karapetis CS. Colorectal cancer: metastases to a single organ. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:11767–11776. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i41.11767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mitry E, Guiu B, Cosconea S, Jooste V, Faivre J, Bouvier AM. Epidemiology, management and prognosis of colorectal cancer with lung metastases: a 30-year population-based study. Gut. 2010;59:1383–1388. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.211557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sakorafas GH, Zouros E, Peros G. Applied vascular anatomy of the colon and rectum: clinical implications for the surgical oncologist. Surg Oncol. 2006;15:243–255. doi: 10.1016/j.suronc.2007.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hughes ES, Cuthbertson AM. Recurrence after curative excision of carcinoma of the large bowel. JAMA. 1962;182:1303–1306. doi: 10.1001/jama.1962.03050520001001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Segelman J, Granath F, Holm T, Machado M, Mahteme H, Martling A. Incidence, prevalence and risk factors for peritoneal carcinomatosis from colorectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2012;99:699–705. doi: 10.1002/bjs.8679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aoyagi T, Terracina KP, Raza A, Takabe K. Current treatment options for colon cancer peritoneal carcinomatosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:12493–12500. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i35.12493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Simmonds PC, Primrose JN, Colquitt JL, Garden OJ, Poston GJ, Rees M. Surgical resection of hepatic metastases from colorectal cancer: a systematic review of published studies. Br J Cancer. 2006;94:982–999. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vassos N, Piso P. Metastatic colorectal cancer to the peritoneum: current treatment options. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2018;19:49. doi: 10.1007/s11864-018-0563-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pfannschmidt J, Dienemann H, Hoffmann H. Surgical resection of pulmonary metastases from colorectal cancer: a systematic review of published series. Ann Thorac Surg. 2007;84:324–338. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2007.02.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kobiela J, Spychalski P, Marvaso G, Ciardo D, Dell’Acqua V, Kraja F, Błażyńska-Spychalska A, Łachiński AJ, Surgo A, Glynne-Jones R, Jereczek-Fossa BA. Ablative stereotactic radiotherapy for oligometastatic colorectal cancer: systematic review. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2018;129:91–101. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2018.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Takeda A, Sanuki N, Kunieda E. Role of stereotactic body radiotherapy for oligometastasis from colorectal cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:4220–4229. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i15.4220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.de Gramont A, Figer A, Seymour M, Homerin M, Hmissi A, Cassidy J, Boni C, Cortes-Funes H, Cervantes A, Freyer G, Papamichael D, Le Bail N, Louvet C, Hendler D, de Braud F, Wilson C, Morvan F, Bonetti A. Leucovorin and fluorouracil with or without oxaliplatin as first-line treatment in advanced colorectal cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2000;18:2938–2947. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.16.2938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goldberg RM, Sargent DJ, Morton RF, Fuchs CS, Ramanathan RK, Williamson SK, Findlay BP, Pitot HC, Alberts SR. A randomized controlled trial of fluorouracil plus leucovorin, irinotecan, and oxaliplatin combinations in patients with previously untreated metastatic colorectal cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2004;22:23–30. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.09.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cassidy J, Clarke S, Díaz-Rubio E, Scheithauer W, Figer A, Wong R, Koski S, Lichinitser M, Yang TS, Rivera F, Couture F, Sirzén F, Saltz L. Randomized phase III study of capecitabine plus oxaliplatin compared with fluorouracil/folinic acid plus oxaliplatin as first-line therapy for metastatic colorectal cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2008;26:2006–2012. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.9898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Falcone A, Ricci S, Brunetti I, Pfanner E, Allegrini G, Barbara C, Crinò L, Benedetti G, Evangelista W, Fanchini L, Cortesi E, Picone V, Vitello S, Chiara S, Granetto C, Porcile G, Fioretto L, Orlandini C, Andreuccetti M, Masi G. Phase III trial of infusional fluorouracil, leucovorin, oxaliplatin, and irinotecan (FOLFOXIRI) compared with infusional fluorouracil, leucovorin, and irinotecan (FOLFIRI) as first-line treatment for metastatic colorectal cancer: the Gruppo Oncologico Nord Ovest. J. Clin. Oncol. 2007;25:1670–1676. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.0928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Passardi A, Nanni O, Tassinari D, Turci D, Cavanna L, Fontana A, Ruscelli S, Mucciarini C, Lorusso V, Ragazzini A, Frassineti GL, Amadori D. Effectiveness of bevacizumab added to standard chemotherapy in metastatic colorectal cancer: final results for first-line treatment from the ITACa randomized clinical trial. Ann Oncol. 2015;26:1201–1207. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdv130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hurwitz H, Fehrenbacher L, Novotny W, Cartwright T, Hainsworth J, Heim W, Berlin J, Baron A, Griffing S, Holmgren E, Ferrara N, Fyfe G, Rogers B, Ross R, Kabbinavar F. Bevacizumab plus irinotecan, fluorouracil, and leucovorin for metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2335–2342. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Saltz LB, Clarke S, Díaz-Rubio E, Scheithauer W, Figer A, Wong R, Koski S, Lichinitser M, Yang TS, Rivera F, Couture F, Sirzén F, Cassidy J. Bevacizumab in combination with oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy as first-line therapy in metastatic colorectal cancer: a randomized phase III study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2008;26:2013–2019. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.9930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stintzing S, Modest DP, Rossius L, Lerch MM, von Weikersthal LF, Decker T, Kiani A, Vehling-Kaiser U, Al-Batran SE, Heintges T, Lerchenmüller C, Kahl C, Seipelt G, Kullmann F, Stauch M, Scheithauer W, Held S, Giessen-Jung C, Moehler M, Jagenburg A, Kirchner T, Jung A, Heinemann V. FOLFIRI plus cetuximab versus FOLFIRI plus bevacizumab for metastatic colorectal cancer (FIRE-3): a post-hoc analysis of tumour dynamics in the final RAS wild-type subgroup of this randomised open-label phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17:1426–1434. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30269-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Heinemann V, von Weikersthal LF, Decker T, Kiani A, Vehling-Kaiser U, Al-Batran SE, Heintges T, Lerchenmüller C, Kahl C, Seipelt G, Kullmann F, Stauch M, Scheithauer W, Hielscher J, Scholz M, Müller S, Link H, Niederle N, Rost A, Höffkes HG, Moehler M, Lindig RU, Modest DP, Rossius L, Kirchner T, Jung A, Stintzing S. FOLFIRI plus cetuximab versus FOLFIRI plus bevacizumab as first-line treatment for patients with metastatic colorectal cancer (FIRE-3): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:1065–1075. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70330-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Karapetis CS, Khambata-Ford S, Jonker DJ, O’Callaghan CJ, Tu D, Tebbutt NC, Simes RJ, Chalchal H, Shapiro JD, Robitaille S, Price TJ, Shepherd L, Au HJ, Langer C, Moore MJ, Zalcberg JR. K-ras mutations and benefit from cetuximab in advanced colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1757–1765. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0804385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Le DT, Uram JN, Wang H, Bartlett BR, Kemberling H, Eyring AD, Skora AD, Luber BS, Azad NS, Laheru D, Biedrzycki B, Donehower RC, Zaheer A, Fisher GA, Crocenzi TS, Lee JJ, Duffy SM, Goldberg RM, de la Chapelle A, Koshiji M, Bhaijee F, Huebner T, Hruban RH, Wood LD, Cuka N, Pardoll DM, Papadopoulos N, Kinzler KW, Zhou S, Cornish TC, Taube JM, Anders RA, Eshleman JR, Vogelstein B, Diaz LA. PD-1 blockade in tumors with mismatch-repair deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:2509–2520. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1500596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Overman MJ, Lonardi S, Wong KYM, Lenz HJ, Gelsomino F, Aglietta M, Morse MA, Van Cutsem E, McDermott R, Hill A, Sawyer MB, Hendlisz A, Neyns B, Svrcek M, Moss RA, Ledeine JM, Cao ZA, Kamble S, Kopetz S, Andre T. Durable clinical benefit with nivolumab plus ipilimumab in DNA mismatch repair-deficient/microsatellite instability-High metastatic colorectal cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018;36:773–779. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.76.9901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Overman MJ, McDermott R, Leach JL, Lonardi S, Lenz HJ, Morse MA, Desai J, Hill A, Axelson M, Moss RA, Goldberg MV, Cao ZA, Ledeine JM, Maglinte GA, Kopetz S, André T. Nivolumab in patients with metastatic DNA mismatch repair-deficient or microsatellite instability-high colorectal cancer (CheckMate 142): an open-label, multicentre, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18:1182–1191. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30422-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Van Cutsem E, Cervantes A, Adam R, Sobrero A, Van Krieken JH, Aderka D, Aranda Aguilar E, Bardelli A, Benson A, Bodoky G, Ciardiello F, D’Hoore A, Diaz-Rubio E, Douillard JY, Ducreux M, Falcone A, Grothey A, Gruenberger T, Haustermans K, Heinemann V, Hoff P, Köhne CH, Labianca R, Laurent-Puig P, Ma B, Maughan T, Muro K, Normanno N, Österlund P, Oyen WJ, Papamichael D, Pentheroudakis G, Pfeiffer P, Price TJ, Punt C, Ricke J, Roth A, Salazar R, Scheithauer W, Schmoll HJ, Tabernero J, Taïeb J, Tejpar S, Wasan H, Yoshino T, Zaanan A, Arnold D. ESMO consensus guidelines for the management of patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Ann Oncol. 2016;27:1386–1422. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdw235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Poston GJ, Adam R, Alberts S, Curley S, Figueras J, Haller D, Kunstlinger F, Mentha G, Nordlinger B, Patt Y, Primrose J, Roh M, Rougier P, Ruers T, Schmoll HJ, Valls C, Vauthey NJ, Cornelis M, Kahan JP. OncoSurge: a strategy for improving resectability with curative intent in metastatic colorectal cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2005;23:7125–7134. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.08.722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nordlinger B, Sorbye H, Glimelius B, Poston GJ, Schlag PM, Rougier P, Bechstein WO, Primrose JN, Walpole ET, Finch-Jones M, Jaeck D, Mirza D, Parks RW, Mauer M, Tanis E, Van Cutsem E, Scheithauer W, Gruenberger T. Perioperative FOLFOX4 chemotherapy and surgery versus surgery alone for resectable liver metastases from colorectal cancer (EORTC 40983): long-term results of a randomised, controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:1208–1215. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70447-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Warwick R, Page R. Resection of pulmonary metastases from colorectal carcinoma. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2007;33(Suppl 2):S59–63. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2007.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McAfee MK, Allen MS, Trastek VF, Ilstrup DM, Deschamps C, Pairolero PC. Colorectal lung metastases: results of surgical excision. Ann Thorac Surg. 1992;53:780–786. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(92)91435-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kuijpers AM, Mirck B, Aalbers AG, Nienhuijs SW, de Hingh IH, Wiezer MJ, van Ramshorst B, van Ginkel RJ, Havenga K, Bremers AJ, de Wilt JH, Te VE, Verwaal VJ. Cytoreduction and HIPEC in the netherlands: nationwide long-term outcome following the Dutch protocol. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20:4224–4230. doi: 10.1245/s10434-013-3145-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ychou M, Hohenberger W, Thezenas S, Navarro M, Maurel J, Bokemeyer C, Shacham-Shmueli E, Rivera F, Kwok-Keung Choi C, Santoro A. A randomized phase III study comparing adjuvant 5-fluorouracil/folinic acid with FOLFIRI in patients following complete resection of liver metastases from colorectal cancer. Ann Oncol. 2009;20:1964–1970. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdp236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Coskun U, Buyukberber S, Yaman E, Uner A, Er O, Ozkan M, Dikilitas M, Oguz M, Yildiz R, B DY, Kaya AO, Benekli M. Xelox (capecitabine plus oxaliplatin) as neoadjuvant chemotherapy of unresectable liver metastases in colorectal cancer patients. Neoplasma. 2008;55:65–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Masi G, Cupini S, Marcucci L, Cerri E, Loupakis F, Allegrini G, Brunetti IM, Pfanner E, Viti M, Goletti O, Filipponi F, Falcone A. Treatment with 5-fluorouracil/folinic acid, oxaliplatin, and irinotecan enables surgical resection of metastases in patients with initially unresectable metastatic colorectal cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2006;13:58–65. doi: 10.1245/ASO.2006.03.094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Inoue Y, Miki C, Hiro J, Ojima E, Yamakado K, Takeda K, Kusunoki M. Improved survival using multi-modality therapy in patients with lung metastases from colorectal cancer: a preliminary study. Oncol Rep. 2005;14:1571–1576. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Petre EN, Jia X, Thornton RH, Sofocleous CT, Alago W, Kemeny NE, Solomon SB. Treatment of pulmonary colorectal metastases by radiofrequency ablation. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2013;12:37–44. doi: 10.1016/j.clcc.2012.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nishiofuku H, Tanaka T, Matsuoka M, Otsuji T, Anai H, Sueyoshi S, Inaba Y, Koyama F, Sho M, Nakajima Y, Kichikawa K. Transcatheter arterial chemoembolization using cisplatin powder mixed with degradable starch microspheres for colorectal liver metastases after FOLFOX failure: results of a phase I/II study. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2013;24:56–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2012.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Van Cutsem E, Köhne CH, Hitre E, Zaluski J, Chang Chien CR, Makhson A, D’Haens G, Pintér T, Lim R, Bodoky G, Roh JK, Folprecht G, Ruff P, Stroh C, Tejpar S, Schlichting M, Nippgen J, Rougier P. Cetuximab and chemotherapy as initial treatment for metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1408–1417. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0805019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bokemeyer C, Bondarenko I, Makhson A, Hartmann JT, Aparicio J, de Braud F, Donea S, Ludwig H, Schuch G, Stroh C, Loos AH, Zubel A, Koralewski P. Fluorouracil, leucovorin, and oxaliplatin with and without cetuximab in the first-line treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2009;27:663–671. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.8397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Berger MD, Lenz HJ. The safety of monoclonal antibodies for treatment of colorectal cancer. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2016;15:799–808. doi: 10.1517/14740338.2016.1167186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sheth KR, Clary BM. Management of hepatic metastases from colorectal cancer. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2005;18:215–223. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-916282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Abdalla EK, Vauthey JN, Ellis LM, Ellis V, Pollock R, Broglio KR, Hess K, Curley SA. Recurrence and outcomes following hepatic resection, radiofrequency ablation, and combined resection/ablation for colorectal liver metastases. Ann Surg. 2004;239:818–825. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000128305.90650.71. discussion 825-817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Van Cutsem E, Cervantes A, Nordlinger B, Arnold D. Metastatic colorectal cancer: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2014;25(Suppl 3):iii1–9. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tan KK, Lopes Gde L, Sim R. How uncommon are isolated lung metastases in colorectal cancer? A review from database of 754 patients over 4 years. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13:642–648. doi: 10.1007/s11605-008-0757-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Embún R, Fiorentino F, Treasure T, Rivas JJ, Molins L Grupo Español de Cirugía Metástasis Pulmonares de Carcinoma Colo-Rectal (GECMP-CCR) de la Sociedad Española de Neumoloña y Cirurña Torácica (SEPAR) (See appendix for membership of GECMP-CCR-SE. Pulmonary metastasectomy in colorectal cancer: a prospective study of demography and clinical characteristics of 543 patients in the Spanish colorectal metastasectomy registry (GECMP-CCR) BMJ Open. 2013;3 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-002787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tampellini M, Ottone A, Bellini E, Alabiso I, Baratelli C, Bitossi R, Brizzi MP, Ferrero A, Sperti E, Leone F, Miraglia S, Forti L, Bertona E, Ardissone F, Berruti A, Alabiso O, Aglietta M, Scagliotti GV. The role of lung metastasis resection in improving outcome of colorectal cancer patients: results from a large retrospective study. Oncologist. 2012;17:1430–1438. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2012-0142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Verwaal VJ, van Ruth S, de Bree E, van Slooten GW, van Tinteren H, Boot H, Zoetmulder FAN. Randomized trial of cytoreduction and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy versus systemic chemotherapy and palliative surgery in patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis of colorectal cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2003;21:3737–3743. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.04.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Halkia E, Kopanakis N, Nikolaou G, Spiliotis J. Cytoreductive surgery and HIPEC for peritoneal carcinomatosis. A review on morbidity and mortality. J BUON. 2015;20(Suppl 1):S80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chua TC, Yan TD, Saxena A, Morris DL. Should the treatment of peritoneal carcinomatosis by cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy still be regarded as a highly morbid procedure?: a systematic review of morbidity and mortality. Ann Surg. 2009;249:900–907. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181a45d86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shibata D, Paty PB, Guillem JG, Wong WD, Cohen AM. Surgical management of isolated retroperitoneal recurrences of colorectal carcinoma. Dis Colon Rectum. 2002;45:795–801. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-6300-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ismaili N. Treatment of colorectal liver metastases. World J Surg Oncol. 2011;9:154. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-9-154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Skof E, Rebersek M, Hlebanja Z, Ocvirk J. Capecitabine plus Irinotecan (XELIRI regimen) compared to 5-FU/LV plus Irinotecan (FOLFIRI regimen) as neoadjuvant treatment for patients with unresectable liver-only metastases of metastatic colorectal cancer: a randomised prospective phase II trial. BMC Cancer. 2009;9:120. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-9-120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nordlinger B, Van Cutsem E, Rougier P, Köhne CH, Ychou M, Sobrero A, Adam R, Arvidsson D, Carrato A, Georgoulias V, Giuliante F, Glimelius B, Golling M, Gruenberger T, Tabernero J, Wasan H, Poston G European Colorectal Metastases Treatment Group. Does chemotherapy prior to liver resection increase the potential for cure in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer? A report from the European Colorectal Metastases Treatment Group. Eur J Cancer. 2007;43:2037–2045. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2007.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gruenberger B, Tamandl D, Schueller J, Scheithauer W, Zielinski C, Herbst F, Gruenberger T. Bevacizumab, capecitabine, and oxaliplatin as neoadjuvant therapy for patients with potentially curable metastatic colorectal cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2008;26:1830–1835. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.7679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nozawa H, Takiyama H, Hasegawa K, Kawai K, Hata K, Tanaka T, Nishikawa T, Sasaki K, Kaneko M, Murono K, Emoto S, Sonoda H, Nakajima J. Adjuvant chemotherapy improves prognosis of resectable stage IV colorectal cancer: a comparative study using inverse probability of treatment weighting. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2019;11:1758835919838960. doi: 10.1177/1758835919838960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]