Abstract

Leukocyte immunoglobulin (Ig)-like receptor B4 (LILRB4) is a member of leukocyte Ig-like receptors (LILRs), which associate with membrane adaptors to signal through multiple cytoplasmic immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibitory motifs (ITIMs). Under physiological conditions, LILRB4 plays a very important role in the function of the immune system through its expression on various immune cells, such as T cells and plasma cells. Under pathological conditions, LILRB4 affects the processes of various diseases, such as the transformation and infiltration of tumors and leukemias, through various signaling pathways. Differential expression of LILRB4 is present in a variety of immune system diseases, such as Kawasaki disease, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), and sepsis. Recent studies have shown that LILRB4 also plays a role in mental illness. The important role of LILRB4 in the immune system and its differential expression in a variety of diseases make LILRB4 a potential prophylactic and therapeutic target for a variety of diseases.

Keywords: LILRB4, immunology, tumor, leukemia, inflammation

Introduction

Leukocyte immunoglobulin-like receptor (LILRB4) is a kind of inhibitory receptor that plays a key role in immune checkpoint pathways. Inhibitory receptors also participate in achieving balance between activating and inhibitory actions to ensure immune responses to pathogens in the immune system. However, they not only protect the host from autoimmune responses, but also preserve peripheral tolerance [1]. LILRB4 also regulates immune responses, and its role in regulating immune responses is mostly controlled by its ligands [2].

The leukocyte Ig-like receptor (LILR) family, the members of which are also called leukocyte immunoglobulin-like receptors (LIRs or ILTs), has 13 members (two pseudogenes are included) [3,4]. LILRs are one of the seven types of leukocyte immunoglobulin-like inhibitory receptors, along with killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptors 2D, killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptors 3D, glycoprotein receptors (such as GP-49), paired immunoglobulin-like receptors, leukocyte-associated Ig-like receptors and inhibitory IgG Fc receptors (such as FcγRIIb1), and they have been identified in the human hematopoietic system [5].

Structure

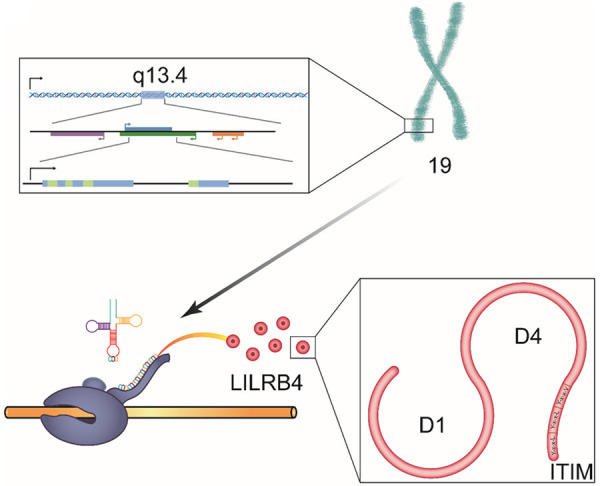

LILRB4 is an LILR and is encoded in the leukocyte receptor cluster, which is on human chromosome 19q13.4 [4-6]. The structure and function of LILRs are similar to those of other leukocyte receptor cluster receptors, such as killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptors [3].

There are many kinds of classifications of LILRs. Among all these classifications, the most classical one is the one proposed by Willcox. In this classification, LILRs are divided into two groups according to whether they have high conservation of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) binding residues to interact with MHC class I or MHC class I-like proteins [3]. Other classifications divide LILRs into two groups according the different motifs: the inhibitory LILR subfamily B group (LILRB1-5), which associate with membrane adaptors to signal through multiple cytoplasmic immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibitory motifs (ITIMs), and the activating LILR subfamily A group (LILRA1-6), which associate with membrane adaptors to signal through immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activating motifs [7,8]. In regard to signals transmitted by LILRs, both ITIMs and immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activating motifs are of great significance [9]. In addition, LILRB4 has three ITIMs [10] (Figure 1) [3,5,10]. Differences between LILRs are summarized in Table 1 [3,7,11].

Figure 1.

The structure of LILRB4. LILRB4 is encoded on human chromosome 19q13.4. It has two C-type lg-like domains, D1 and D4. Three ITIMs of LILRB4 are of the YxxV sequence, and two are of the YxxL sequence, and they are located in the cytoplasmic tail. In addition, LILRB4 can recruit SHP-1 to downregulate activation signals, which is mediated by nonreceptor tyrosine kinase cascades.

Table 1.

LILRs (omit the two pseudo-genes LILRP1 (ILT9) and LILRP2 (ILT11))

| Receptor | Lg-like domains | Ligands | Expression | Diseases concerned | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LILRA1 (LIR-6, CD85i) | D1, D2, D3, and D4 | MHC-I, HLA-B27 FHC | monocytes and B cells | NA | [3,7,11] |

| LILRA2 (ILT1, LIR-7, CD85h) | D1, D2, D3, and D4 | MHC-I | minor subsets of T- and natural killer (NK) cells, monocytes, macrophages, dendritic cells (DCs) and granulocytes | leprosy | [3,7,11] |

| LILRA3 (ILT6, LIR-4, CD85e) | D1, D2, D3, and D4 | MHC-I | secreted by monocytes, B cells and subsets of T-cells | multiple sclerosis, Sjögren’s syndrome, SLE, prostate cancer | [3,7,11] |

| LILRA4 (ILT7, CD85g) | D1, D2, D3, and D4 | Ag 2 (BST2) | plasmacytoid DCs | NA | [3,7,11] |

| LILRA5 (ILT11, LIR-9, CD85f) | D1, D2 | NA | monocytes and neutrophils | NA | [3,7,11] |

| LILRA6 (ILT8, CD85b) | D1, D2, D3, and D4 | NA | monocytes | NA | [3,7,11] |

| LILRB1 (ILT2, LIR-1, CD85j) | D1, D2, D3, and D4 | MHC-I | T, B, NK and myeloid cells | human cytomegalovirus (HCMV), dengue virus | [3,7,11] |

| LILRB2 (ILT4, LIR-2, CD85d) | D1, D2, D3, and D4 | MHC-I | myeloid cells, hematopoietic stem cells | Alzheimer’s disease | [3,7,11] |

| LILRB3 (ILT5, LIR-3, CD85a) | D1, D2, D3, and D4 | NA | monocytes, DCs and granulocytes | Leukemia | [3,7,11] |

| LILRB4 (ILT3, LIR-5, CD85k) | D1, D4 | unknown | monocytes, macrophages, DCs and plasma cells | SLE, Kawasaki disease, T. gondii, multiple sclerosis | [3,7,11,17,26] |

| LILRB5 (LIR-8, CD85c) | D1, D2, D3, and D4 | HLA-B27 FHC | NK cells, monocytes and mast cell granules | NA | [3,7,11] |

LILR: leukocyte immunoglobulin-like receptor; ILT: Leukocyte immunoglobulin-like receptor; MHC: major histocompatibility complex; SLE: systemic lupus erythematosus; HLA: human lymphocyte antigen; Ag: antigen; BST: bone marrow stromal antigen.

It is worth mentioning that most family members contain four C-type Ig-like domains in their extracellular region (designated D1, D2, D3, and D4); however, LILRB4 and LILRA5 have only two. In addition, LILRB4 is distinguished by an unusual domain organization, which consists of a classical LILR D1 domain and an immunoglobulin domain that is most similar to the membrane-proximal D4 domain of other LILRs [3,12] (Table 1). In addition, LILRB4 has three specific amino acid residues, R56, R101, and V104 [13]. The natural ligand (s) for LILRB4 are still not clear [10]. However, the natural ligand for gp49B the mouse counterpart of LILRB4, is integrin avb3 [14].

Distribution

The expression of LILRB4 is confined to professional and nonprofessional antigen-presenting cells (APCs) [4]. LILRs are mainly expressed on cells of the myelomonocytic lineage [15], for example, monocytes, macrophages and dendritic cells [16]. In cells of the myelomonocytic lineage, LILRB4 is mostly expressed on APCs [17]. For many cells, such as APCs, myeloid-derived suppressor cells, plasmacytoid dendritic cells (DCs) and monocytic DCs, LILRB4 is generally referred to as a tolerogenic receptor [18]. In addition, by inhibiting the expression of costimulatory molecules, LILRB4-expressing APCs play key roles in controlling inflammation. Likewise, LILRB4 neutralization can increase antigen presentation [17]. Furthermore, LILRB4 can be expressed both on the cell membrane and/or in the cytoplasm [19].

Relationship with disease

As immune checkpoints are of great significance in autoimmune diseases, LILRB4 is a target for treating autoimmune diseases [20]. LILRB4 is associated with many kinds of immune diseases, such as Kawasaki disease and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). In addition, LILRB4 plays an effective role in inflammatory diseases. As nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-kappa B) is a common transcription factor that participates in angiogenesis, cell proliferation and cell survival [21], LILRB4 can promote cardiac dysfunction and fibrosis, and it can also lead to apoptosis via NF-kappa B signaling [22] and inflammation by activating NF-kappa B signaling through reduced phosphatase (SHP) 1 phosphorylation [23]. LILRB4 also has the ability to inhibit the development of tumors [24]. For example, LILRB4 is also an effective target for acute myeloid leukemia (AML) treatment [25]. Furthermore, it is presumed that LILRB4 also participates in the basic mechanisms of central nervous system (CNS) immune surveillance. As a result, LILRB4 is associated with some neurological diseases, such as multiple sclerosis [26].

Physiological role of LILRB4

As one of the LILR family members, LILRB4’s main function is to play a role in the immune response to infection [15]. It can participate in different mechanisms in many immune cells.

Immune cells

T cells

LILRB1 is the only human LILRB protein that can be expressed on T cells. LILRB1 expression on T cells can decrease the expression of chemokine receptors [27]. Although LILRB4 is not expressed on T cells, it can recognize unidentified ligands expressed on them [18], and it elicits T cell anergy or activation of regulatory T (Treg) cells or T suppressor cells [28]. Because of the bidirectional signaling properties of LILRB4, LILRB4 can not only transduce signals through its intracellular domain but also directly modulate the binding of its extracellular Ig-like domain [29]. As a result, LILR-Fcs, the soluble forms of LILR, are effective inhibitors of T cell proliferation, even in the absence of APCs [26]. LILRB4 can still inhibit T cells with its extracellular domain even when the ITIM-containing cytoplasmic tail is deleted. A study used a soluble form of LILRB4, expressed as an LILRB4-Fc fusion protein, and found that LILRB4-Fc could inhibit T cell immune/inflammatory responses as a result of inhibiting the release of inflammatory microRNA [30,31]. For T cells with cognate specificity, LILRB4 can also induce anergy and plays a regulatory function [32].

In addition, T cells elicit the upregulation of LILRB2 and LILRB4 expression on APCs, which makes them tolerogenic to T cells. Furthermore, recombinant LILRB4-Fc has also been shown to activate T cell responses through induction of T helper cell (Th) anergy and differentiation of CD8+ T suppressor cells, as well as promotion of the induction of immunological tolerance [3,12]. Blockade of inhibitory receptors leads to the generation of cytolytic CD8+ T cells that are able to recognize APCs and is of great significance when tumors and viruses invade bodies [33].

In Tregcells, the regulation of LILRB4 expression by CK2 is supposed to represent a regulatory mechanism of the adaptive immune response that enables the transient inhibition of suppressor cells at the time when a fulminant immune response is required [34]. In addition, Treg cells can produce interleukin-10 (IL-10), resulting in modulation of the dendritic cell phenotype via downregulation of MHC class II molecules, CD80 and CD86 and upregulation of LILRB4 [35].

Granulocytes

Granulocytes, including neutrophils, basophils, and eosinophils, provide a rapid response in the early stages of immune challenge through the release of secretory granules. LILRB1, LILRB2, LILRB3, and LILRA2 are expressed by eosinophils [9].

Human neutrophils can act as nonprofessional APCs. In adaptive immunity, human neutrophils play an immunoregulatory role. On circulating human neutrophils, some coinhibitory molecules, such as LILRB2 and LILRB3, are expressed, while LILRB4 is not expressed [36]. However, LILRB4 can counterregulate lipopolysaccharide-mediated inflammation in several neutrophil-dependent acute effector phases [37], which means that LILRB4 contributes to the inhibition of neutrophil-dependent inflammation in vitro [38]. Furthermore, under normal physiological conditions, LILRB4 suppresses the lipopolysaccharide-induced increase in intravascular neutrophil adhesion, which provides critical innate protection against an excessive pathologic response to a bacterial component [39].

Dendritic cells

DCs are the only immune cells that can induce primary immune responses, and they can also permit the formation of immunological memory [40], as well as maintain the balance between tolerance and immunity [41]. Immature DCs have been shown to have the ability to reduce antigen stimulation [42], and mature dendritic cells are the most potent and efficient APCs [5,43], which suggests that the tolerance-inducing potential of DCs is related to their maturation status [44]. The differential expression of LILRB4 during the maturation of DCs suggests an important role of LILRB4 in promoting DC maturation [45].

LILRB4 expression on DCs influences the development of diseases. Overexpression of LILRB4 can inhibit the transcription of NF-κB-dependent genes that encode costimulatory molecules (CD80 and CD86) in DCs. As inflammation and apoptosis mostly induced through NF-κB signaling, overexpression of LILRB4 can inhibit them. In addition, the differentiation of CD8 T or CD4 single-positive T cells is not possible [46-48].

In the context of protective adaptive immunity and inflammation, in response to Salmonella infection or Toll-like receptor stimulation with Salmonella components, LILRB4 expression on DCs and macrophages is upregulated, which suggests that LILRB4 plays a physiologic role in limiting the inflammatory response during infection [46].

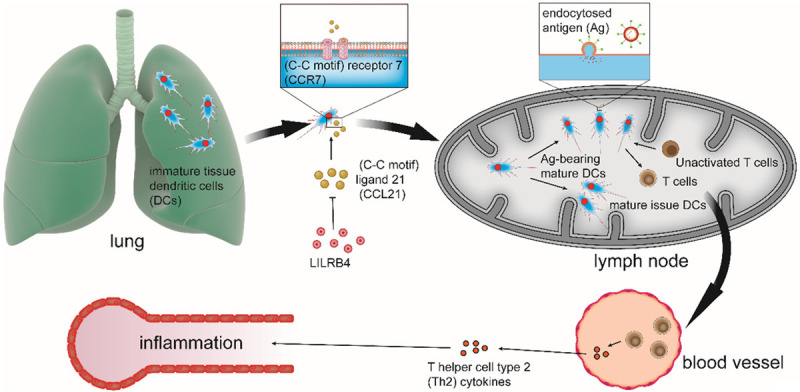

In addition, in regard to pathologic adaptive immunity and inflammation, LILRB4 also plays a significant role. For example, in lipopolysaccharide-mediated inflammation [37], which upregulates LILRB4 expression on human DCs [49], LILRB4 is important during the immune responses. There are two kinds of mechanisms. In one mechanism, LILRB4 weakens the ability of DCs by affecting the number of mature dendritic cells and attendant IL-4-producing lymphocytes in lymph nodes, which is a key molecule needed for DC migration. For example, LILRB4 can elicit pathologic Th2 pulmonary inflammation [27,37]. In addition, it has been shown that LILRB4 can counterregulate the development of pathologic adaptive immune responses initiated by an innate immune signal; when left unchecked, these types of responses make a harmless and tolerizing molecule immunogenic which represents a critical step in the development of allergic airway disease [37]. Another mechanism suggests that LILRB4 may regulate the transformation of the innate response into an adaptive response by inhibiting cell chemotaxis. It has been shown that ITIM-bearing receptors can play inhibitory roles by downregulating the expression of both stromal chemokines and their cognate receptors on immune cells, which leads to attenuated cell migration and pathologic allergic inflammation. In this way, LILRB4 inhibits chemotaxis and migration of DCs from the lung to secondary lymphoid tissue, which downregulates DC-T cell interactions to suppress this kind of inflammation (Figure 2) [27].

Figure 2.

LILRB4 inhibits chemotaxis and migration of DCs from the lung to secondary lymphoid tissues. In the context of pulmonary allergic inflammation, immature tissue dendritic cells (DCs) go through an innate immune maturation process. During this process, mature issue DCs will migrate from the lung to tissue-draining lymph nodes (LNs), which is mediated by chemokine (C-C motif) receptor 7 (CCR7), the only receptor of chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 21 (CCL21). In addition, some mature DCs degrade endocytosed antigen (Ag) and turn into Ag-bearing mature DCs. Ag-bearing mature DCs attract and activate cognate Ag-specific T cells, which leads to their proliferation, polarization, and migration from the LNs to the blood. At the same time, Ag-bearing mature DCs generate Th2 cytokines. Th2 cytokines can migrate to target tissues, where they can lead to pathologic adaptive immune inflammation. The function of LILRB4 is to downregulate the expression of CCL21 to inhibit chemotaxis and migration of DCs from the lung to secondary lymphoid tissues, which can suppress inflammation.

However, the mechanism still needs to be studied. In some diseases, although LILRB4 expression is upregulated, the tolerogenic role of LILRB4 has not be shown, and the reasons for this remain unknown. For example, in SLE, LILRB4 cannot play an effective role. One study showed that the type I interferon (IFN) pathway participates in the pathogenesis of SLE, and IFNs can induce LILRB4 expression by plasmacytoid DCs and mature dendritic cells [18].

Macrophages

Macrophages are the main immune cells located in the lung tissue [38]. LILRB4 ligation changes the cytokine secretion profile of macrophages, and it also leads to an upregulation of IL-10 secretion by in vitro-cultured macrophages. In addition, it reduces the expression of the strongly inflammatory chemokine IL-8 [15].

LILRB4 and LILRB5 can activate the JAK/STAT signaling pathway and control the expression of cytokines in macrophages. They also induce the expression of chemokines and Th1, Th2, and Th17 cytokines, which suggests that they are innate immune receptors related to SHP-2, MHC class I, and beta 2-microglobulin [50,51].

Monocytes

Depending on the nature of the stimuli and the position of the tyrosine residue in LILRB4 ITIMs, LILRB4 may have complex inhibitory and activating effects on monocytes [10].

Through triggering dephosphorylation of key signaling proteins, LILRB4 inhibits FcγRI-mediated cytokine production and regulates endocytosis/phagocytosis on monocytes [52].

Silencing of LILRB4 in monocyte-derived dendritic cells potentiates stimulus-induced release of chemokines, which may be involved in T cell trafficking to the CNS [53].

B cells

LILRB4 is not expressed on normal B cells [54]. However, in memory B cells, gp49b, the mouse counterpart of LILRB4, suppresses the development of marginal zone B cells, memory B cells and Ab production to prevent excessive IgE production, which would otherwise lead to allergic diseases [1,55]. In addition, in some diseases, such as pulmonary embolism, LILRB4 expression is upregulated [56], suggesting that LILRB4 plays a role in the immune response in B cells.

Natural killer (NK) cells

NK cells express inhibitory receptors, which recognize distinct ‘self’ class I molecules of the major histocompatibility complex, and in addition, NK cells can lyse tumor or virus-infected cells [57]. In human NK cells, a family of ITIM-bearing receptors called killer cell Ig-like receptor (KIRs) are expressed. KIRs have significant sequence homology with LILRB4 and can recognize MHC class I allotypes. A chimeric receptor consisting of the extracellular and transmembrane domains of a human KIR is expressed on NK cells from humans infected with cytomegalovirus or lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus [58]. After infection with vaccinia virus, LILRB4 expression is elicited on NK cells and T cells [59].

Mast cells

Mast cells participate in many physiological mechanisms and play a significant role in antimicrobial defense [14].

LILRB4 inhibits IgE-dependent activation of mast cells in vitro through its ITIMs, which recruit src homology domain type-2-containing tyrosine phosphatase 1 to the cell membrane. In addition, LILRB4 could counterregulate the shock induced during active systemic anaphylaxis, which is probably elicited by inhibition of FcR-induced mast cell degranulation. Furthermore, for mast cells, stem cell factor is an essential growth and survival factor [39], which has the ability to activate mast cells [60].

Microglia

Microglia are immune cells of the CNS, and LILRB4 expression increases when microglia participate in the immune response [61]. CD11c-positive microglia, which represent 23% of all activated microglia, play a role in the inflammatory response in the context of Alzheimer’s disease [62].

Immunologically active substances

Interleukins (ILs)

IL-10 is a kind of anti-inflammatory cytokine [63], and it has immune-stimulating and immunosuppressive dual biological functions [64]. As IL-10 can upregulate LILRB1, LILRB2, LILRB3 and LILRB4 on APCs, IL-10 is an inhibitory cytokine that may result in a feedback loop of LILR-mediated inhibition. This means that IL-10 is an effective anti-inflammatory factor [15].

For DCs, one kind of IL-10-producing DC called DC-10 has been identified in the human body and secretes high levels of IL-10 [65]. In addition, DCs treated with resveratrol are more effective in producing IL-10 than untreated DCs [66].

Pathological role of LILRB4

LILRB4 is considered to be an inhibitor of T cell activation in transplantation, autoimmunity and allergy [67] and has obvious differential expression in many kinds of immune-related diseases. As such, research on the pathological role of LILRB4 is valuable and important.

Tumors

In patients with malignant tumors, LILRB4 inhibits CD4+ Th cell proliferation by binding to the ligand CD166 (activated leukocyte adhesion molecule) and CD8+CD28- T cell production and promotes tumor growth and tumor infiltration [24,68-71]. In 2019, Tomic, S. et al. showed that prostaglandin E2 could induce different subpopulations of Treg cells through effects of LILRB4 on myeloid-derived suppressor cells, a major cell type driving tumor progression, by using a protocol for the generation of mononuclear (M)-MDSCs [72]. It should be noted that the ability of LILRB4 to induce cancer stem cell (CSC) differentiation into macrophages has been proven by follow-up studies, which implies a connection to the tumor microenvironment [73]. A recent study has shown that LILRB4 plays an essential role during tyramine and tyramine receptor (TyrR) activation [74]. Given its emerging role in tumorigenesis, this finding highlights the relationship between LILRB4 and tumors [75].

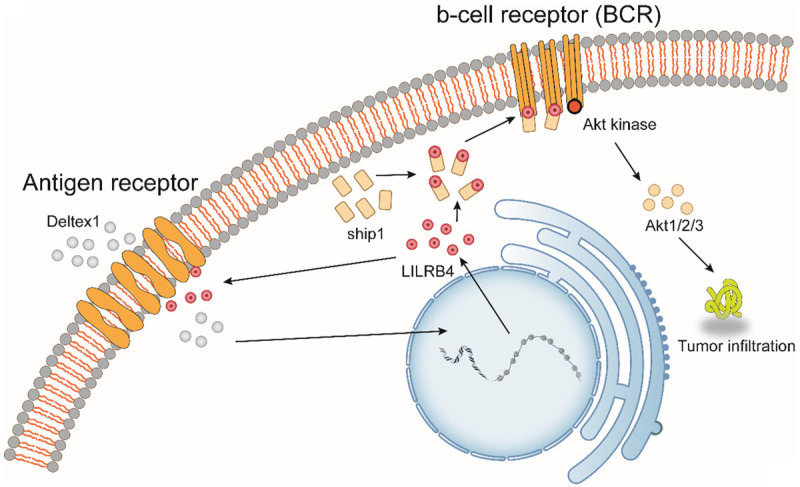

In addition to inducing tumorigenesis, in the development of tumors, the expression of LILRB4 may induce immunosuppression and affect the survival rate of patients. For example, by comparing peripheral blood monocytes in samples from 105 patients with non-small-cell lung cancer and 20 controls, de Goeje, P. L. et al. found that the expression of LILRB4 on myeloid-derived suppressor cells is associated with decreased survival in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer [28,76]. In serum cytokine mediator analysis in hepatocellular carcinoma samples, the serum levels of LILRB4 in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma were significantly higher than those in patients in the control group [77]. High levels of LILRB4 may have some association with tumor development. As early as 2007, an experimental study using a humanized severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) animal model by Cortesini, R. et al. has shown that LILRB4 depletion or blockade in patients with pancreatic cancer is crucial to the success of immunotherapy [78]. In the immune escape of tumor cells, the expression of LILRB4 may affect the sensitizing activity of antigen-presenting cells and is therefore the cause of the failure of interventions to enhance the immune response of patients to malignant tumors such as gastric cancer and pancreatic cancer [79]. In terms of specific intervention pathways, there is growing evidence that LILRB4 may be involved in the regulation of tumor progression by inhibiting the Akt pathway; therefore, LILRB4 has been identified as a marker for malignancy [80,81] (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Dual role of LILRB4 during tumorigenesis. LILRB4 has dual effects in cancer. On the one hand, immune cells escape from tumor cells by affecting the activity of antigen-presenting cells; on the other hand, LILRB4 expression is upregulated under the action of the lymphocyte antigen receptor signal inhibitor Deltex1. A large amount of LILRB4 interacts with phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-triphosphate 5-phosphatase 1 on the cell surface to inhibit the activity of Akt kinase. Decreased Akt kinase activity affects the downstream Akt pathway, which in turn inhibits tumor invasion.

However, the expression of LILRB4 does not necessarily contribute to the development of tumors. Studies by Park, M. et al. indicate that LILRB4 may have dual inhibitory and activating functions depending on the location and/or stimulatory nature of functional tyrosine residues in ITIMs [10]. Si, Y. Q. et al. also found that LILRB4 was upregulated during the killing of tumor cells by cyclosporine [2]. Schmid, A. S. et al. constructed an antibody fusion protein that enhances neutrophil activity by using granulocyte colony-stimulating factor and LILRB4 as payloads. The results of animal experiments show that this novel fusion protein can be expressed and efficiently delivered to the tumor site and kill tumor cells [82] (Figure 3).

Leukemia

LILRB4 expression is acquired at an early stage by normal myelomonocytic precursors [83]. Pathological changes in bone marrow cells often lead to the occurrence of leukemia. In this process, the expression of LILRB4 is worth exploring.

Multiple studies have shown that the expression of LILRB4 in single AML cells was higher than that in normal cells [84], and the expression of LILRB4 was negatively correlated with the overall survival of AML patients [13,80,83]. In patients with AML, LILRB4 inhibits T cell activation by upregulating the expression of various T cell inhibitors, such as BCL6, and promotes the development of AML [83,85,86]. In addition, the interleukin-2 receptor, 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D alpha chain (CD25), on AML cells may capture environmental IL-2 and deliver it to peripheral T lymphocytes, resulting in the production of LILRB4 as a growth stimulus for CD25-positive AML cells [87].

During AML cell migration, apolipoprotein E binds AML cells that have infiltrated the tissue through LILRB4, which activates a downstream signaling pathway in combination with T cell suppression and tumor infiltration [25]. Deng, M. et al. employed a murine tumor model and human cells and revealed that LILRB4 coordinates tumor invasion pathways in single leukemia cells by creating an immunosuppressive microenvironment [25]. In the tumor invasion pathway, miR-155 may be the main target of IL-3 signal transduction in primary AML cells. Given the increasingly obvious role of miR-155 in tumorigenesis and the upregulation of the LILRB4 receptor alpha subunit in AML, it seems reasonable to think that LILRB4 may play an important role in the transformation of leukemia [88]. Regarding the relationship between LILRB4 and tyrosine mentioned above, recent research shows that LILRB4 may influence the early pathological process in leukemia through tyrosine kinases [89], while the ITIMs of LILRB4 in AML mediate T cell suppression and AML cell migration [90].

Not only is the high expression of LILRB4 related to the occurrence and development of AML but newer research has also found that high expression of LILRB4 is also associated with complications of AML. Kobayashi, K. et al. found a paraneoplastic hypoleukemia syndrome associated with LILRB4-IgH-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia [91].

Currently, immunological checkpoint blockade therapy has not shown a clinical benefit in treating leukemia. Based on the studies listed above, this may be due to the presence of an immune evasion mechanism in leukemia that creates an immunosuppressive microenvironment through LILRB4 [25]. Fortunately, there are many therapeutic approaches to the treatment of AML through LILRB4, one of which is the monocyte antibody h128-3, which blocks the activation of LILRB4 and inhibits tissue infiltration of single AML cells [92]. John, S. et al. prepared a novel anti-LILRB4 CAR-T cell with high antigen affinity and specificity. These CAR-T cells exhibited highly potent effects on AML cells in vitro and in vivo, specifically targeting single AML cells and were not toxic to normal hematopoietic progenitor cells [85]. Bispecific antibodies developed for the low-affinity LILRB4 receptor CD123 can redirect immune effector cells to AML targets [93,94]. Given its significant expression differences and pathological mechanisms during the development of AML, LILRB4 is an emerging immune target, and treatment with LILRB4 may improve therapeutic effects in AML [95].

Ectopic expression of LILRB4 in chronic lymphocytic leukemia is a prominent feature of tumor B cells and hematopoietic stem cells, and thus LILRB4 is considered to be a selective marker for chronic lymphocytic leukemias. Based on this, many targeted therapies for the treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia have been developed, such as combination therapies including anti-CTLA-4 and anti-LILRB4 agents [95,96]. The LILRB4 receptor is overexpressed in CML cells compared to normal hematopoietic cells and is therefore a receptor target for cancer drug delivery systems. Bellavia, D. et al. designed a novel anticancer agent that is capable of targeting CML cells and inhibiting the growth of cancer cells in vitro and in vivo using LILRB4-containing exosomes [97].

Toxoplasma infection

The expression of LILRB4 is also associated with the outcome of pregnancy. LILRB4 is a central inhibitory receptor of uterine dendritic cells and plays an important immunomodulatory role at the maternal-fetal interface. Infection with Toxoplasma gondii during early pregnancy can cause malformations such as miscarriage and fetal death. Later studies found that the expression levels of functional LILRB4 molecules in the membrane, arginine metabolizing enzymes and related cytokines were abnormal in Toxoplasma gondii infection models, demonstrating that Toxoplasma infection can downregulate LILRB4 in decidual macrophages [98]. Downregulation of LILRB4 enhances M1 macrophage activation and attenuates M2 macrophage tolerance by altering the expression of M1- and M2-related membrane molecules, the synthesis of arginine metabolizing enzymes, and the secretion profile of cytokines. C. H. et al. found that the LILRB4 rs40401 polymorphism was associated with an increased risk of miscarriage in patients undergoing in vitro fertilization by analyzing single nucleotide polymorphisms [99]. A reduction in LILRB4 can regulate the expression of functional molecules (CD80, CD86, HLA-DR or MHC class II) on uterine dendritic cells after infection with Toxoplasma gondii, leading to abnormal pregnancy outcomes [17].

Immune disease

Abnormal expression of LILRB4 may trigger immune-related diseases [100,101]. A large number of animal models show that LILRB4 induces the secretion of proinflammatory cytokines by T cells and B cells, reduces the expression of IL-10 by B cells, and plays an important role in T cell- and B cell-mediated autoimmune diseases (such as SLE) [102]. In autoimmune responses, self-reactive CD4+ T cells can promote effector inflammation and injury through LILRB4-dependent amplification loops, while autoreactive LILRB4+CD4+ T cells accumulating in effector organs stimulate LILRB4+ tissue macrophages to produce systemic chemokines that attract single cells. The newly recruited monocytes differentiate into antigen-presenting cells, stimulating local LILRB4+CD4+ T cell proliferation, thereby amplifying inflammation [103].

Kawasaki disease is an acute systemic vasculitis syndrome that occurs in children and is associated with secretory cells (ASCs) that highly express LILRB4 [46].

SLE is an autoimmune disease. Animal experiments by Wong, Y. L. et al. showed that mouse glycoprotein 49B (gp49B), which corresponds to human LILRB4, is a pathogenic element in SLE [1]. Clinically, in plasma cells from SLE patients, the expression of leukocyte immunoglobulin-like receptor (LILR) B4 is enhanced [104,105]. For these patients with SLE, the enlarged population size of stromal plasma cells and plasma cells with enhanced LILRB4 expression is a characteristic of untreated SLE [18]. Therefore, LILRB4 may be used as a new molecular marker to identify pathogenic cells in SLE.

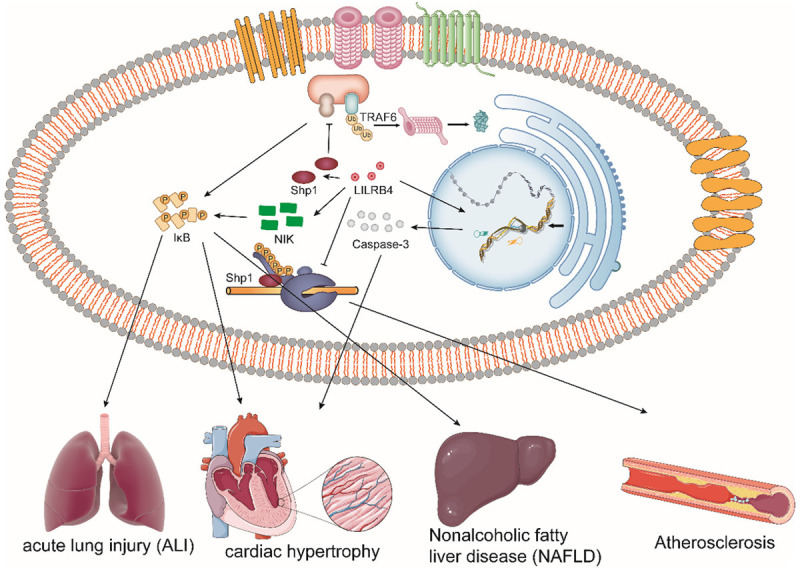

LILRB4 also plays a very important role in the pathological development of various inflammatory diseases. For example, LILRB4 is downregulated in stress-exposed hearts in patient and mice, and mice with LILRB4 knockout develop cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure via promotion of cardiac dysfunction, fibrosis, inflammation, and apoptosis [47,106,107]. During the pathological process of atherosclerosis, the lack of LILRB4 significantly accelerates the development of atherosclerotic lesions by reducing the phosphorylation level of SHP1, leading to characteristic increased lipid infiltration and decreased collagen content [108]. In addition, LILRB4 is also associated with the development of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) [109]. Evidence suggests that the lack of LILRB4 can also aggravate many inflammatory respiratory diseases, such as acute lung injury and asthma, through the NF-kappaB and p38-MAPK signaling pathways [107,110,111]. In addition, high expression of LILRB4 correlates with high mortality in patients with pulmonary tuberculosis (PTB) [112]. Furthermore, a recent transcriptome sequencing and whole-genome expression profiling analysis of pulmonary inflammation in an MWCNT-induced mouse model revealed novel crosstalk between downregulation of LILRB4 and regulation of immunoreactivity genes such as Cd72 in the process of lung inflammation [113] (Figure 4). Therefore, targeting LILRB4 to promote its expression or activation is a promising strategy for the treatment of systemic inflammatory and metabolic diseases. Notably, recent studies have identified that LILRB4 is overexpressed in monocytes from HIV patients [114]. It is highly likely that LILRB4 can affect the pathological process of HIV, albeit experimental evidence is lacking at present.

Figure 4.

The role of LILRB4 in the development of various diseases. The expression of LILRB4 affects the development of various immune diseases. For example, LILRB4 deficiency plays a detrimental role in the activation of macrophages (BMDMs) associated with acute lung injury by promoting the NF-kappaB signaling pathway. The loss of LILRB4 accelerates cardiac hypertrophy by promoting upregulation of caspase-3 activation via the nuclear factor kappaB (NF-kappaB) signaling pathway. LILRB4 inhibits the ubiquitination of TRAF6 by recruiting SHP1, which largely reverses nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). LILRB4 deficiency promotes atherogenesis by reducing Shp1 phosphorylation.

Upregulated expression of LILRB4 has also been found in the treatment of immune diseases. For example, LILRB4 and ILT4 are involved in the regulation of the immune response to multiple sclerosis via interferon and vitamin D [26]. High LILRB4 levels in sepsis patients were independently associated with hospital mortality; therefore, they could be used to predict prognosis in patients with sepsis [115].

The differential expression of LILRB4 in infectious diseases makes it an important biomarker for predicting latent infections. Studies by La Manna, M. P. et al. featured the Luminex Bead Array Multiplex Immunoassay and showed that LILRB4 was significantly higher in the active tuberculosis and long-term tuberculosis groups than in the nontuberculosis group [116]. Consistent with this, high expression of LILRB4 in patients with gram-negative bacterial bloodstream infection was observed, which shows the potential utility for GN-BSI biomarkers [117].

Mental illness

Mounting evidence suggests that LILRB4 signaling may be involved in the pathophysiological process of schizophrenia. For example, LILRB4 was significantly negatively correlated with the immediate memory index in patients with chronic drug-induced schizophrenia, suggesting that IL-3 may be involved in the loss of immediate memory in the chronic phase of schizophrenia [118,119].

Multiple sclerosis is the most common type of central nervous system demyelinating disease. IFN beta can induce the expression of LILRB2 and LILRB4 on monocytes, and this increased expression can be found in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis who are treated with IFN beta. In addition, it has been reported that the effect of IFN beta on these immunomodulatory molecules and monocyte immunobiology is selective [26]. It has been shown that vitamin D and IFN beta can act together to modulate some disease activities [120]. One studied showed that 1α,25(OH)2 D3 could effectively induce LILRB4 on APCs [121], and IFN beta and 1α,25(OH)2 D3 could work together to induce LILRB4 expression on monocytes. As a result, vitamin D cotreatment could have beneficial effects on disease-modifying drugs. Interestingly, IFN beta and 1α,25(OH)2 D3 have the opposite effects on LILRB2 expression on monocytes, which means that IFN beta can be beneficial for the tolerogenic properties of these cells by counteracting the effects of 1α,25(OH)2 D3 on LILRB2 expression. This indicates that LILRB4 may be used as an immunomodulator in autoimmune diseases, which is beneficial for autoimmune disease therapy [26].

Furthermore, it is presumed that LILRB4 also participates in the basic mechanisms of CNS immune surveillance [26]. Silencing of LILRB4 in monocyte-derived dendritic cells potentiates stimulus-induced release of chemokines, which may be involved in T cell trafficking to the CNS [53].

Conclusions

Current studies have found that LILRB4 is differentially expressed in a variety of diseases, indicating that there is great potential for physiological and pathological studies of LILRB4. Some treatments targeting LILRB4 have been attempted, but there is still much room for research on LILRB4. Important research areas that need to be addressed include increasing our understanding of the underlying pathological mechanisms involving LILRB4 at the cellular and molecular levels. LILRB4 has been used as a new biomarker to assess disease activity and achieve early screening and assessment.

Acknowledgements

The present study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 81773179 and 81272972 (C. Ren); grant no. 81472355 (X. Jiang)), Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province (grant no. 2020JJ4771 (C. Ren)), the Hunan Provincial Science and Technology Department (grant no. 2016JC2049 (C. Ren); grant no. 2014FJ6006 (X. Jiang); grant no. GS2019-10533236 (B. Zhou)).

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

Abbreviations

- LILR

leukocyte immunoglobulin-like receptor

- IL

interleukin

- MHC

major histocompatibility complex

- ITIM

immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibitory motif

- APC

antigen-presenting cell

- SLE

systemic lupus erythematosus

- NF-kappa B

nuclear factor-kappa B

- SHP

phosphatase

- AML

acute myeloid leukaemia

- CNS

central nervous system

- Th

T helper cell

- Treg

regulatory T

- DC

dendritic cell

- IFN

interferon

- NK

natural killer

- KIR

killer cell Ig-like receptor

- IL

interleukin

- CD25

interleukin-2 receptor alpha chain

- NAFLD

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

References

- 1.Wong YL, Su MT, Sugahara-Tobinai A, Itoi S, Kezuka D, Endo S, Inui M, Takai T. Gp49B is a pathogenic marker for auto-antibody-producing plasma cells in lupus-prone BXSB/Yaa mice. Int Immunol. 2019;31:397–406. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxz017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Si YQ, Bian XK, Lu N, Jia YF, Hou ZH, Zhang Y. Cyclosporine induces up-regulation of immunoglobulin-like transcripts 3 and 4 expression on and activity of NKL cells. Transplant Proc. 2012;44:1407–1411. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2011.10.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cheng H, Mohammed F, Nam G, Chen Y, Qi J, Garner LI, Allen RL, Yan J, Willcox BE, Gao GF. Crystal structure of leukocyte Ig-like receptor LILRB4 (ILT3/LIR-5/CD85k): a myeloid inhibitory receptor involved in immune tolerance. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:18013–18025. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.221028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gleissner CA, Dengler TJ. Induction of ILT expression on nonprofessional antigen presenting cells: clinical applications. Hum Immunol. 2009;70:357–359. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2009.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arboleda JF, Garcia LF, Alvarez CM. ILT3+/ILT4+ tolerogenic dendritic cells and their influence on allograft survival. Biomedica. 2011;31:281–295. doi: 10.1590/S0120-41572011000200017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kabalak G, Dobberstein SB, Matthias T, Reuter S, The YH, Dorner T, Schmidt RE, Witte T. Association of immunoglobulin-like transcript 6 deficiency with Sjogren’s syndrome. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60:2923–2925. doi: 10.1002/art.24804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van der Touw W, Chen HM, Pan PY, Chen SH. LILRB receptor-mediated regulation of myeloid cell maturation and function. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2017;66:1079–1087. doi: 10.1007/s00262-017-2023-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li Z, Deng M, Huang F, Jin C, Sun S, Chen H, Liu X, He L, Sadek AH, Zhang CC. Correction to: LILRB4 ITIMs mediate the T cell suppression and infiltration of acute myeloid leukemia cells. Cell Mol Immunol. 2020;17:302–304. doi: 10.1038/s41423-019-0351-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown D, Trowsdale J, Allen R. The LILR family: modulators of innate and adaptive immune pathways in health and disease. Tissue Antigens. 2004;64:215–225. doi: 10.1111/j.0001-2815.2004.00290.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Park M, Liu RW, An H, Geczy CL, Thomas PS, Tedla N. A dual positive and negative regulation of monocyte activation by leukocyte Ig-like receptor B4 depends on the position of the tyrosine residues in its ITIMs. Innate Immun. 2017;23:381–391. doi: 10.1177/1753425917699465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hirayasu K, Arase H. Functional and genetic diversity of leukocyte immunoglobulin-like receptor and implication for disease associations. J Hum Genet. 2015;60:703–708. doi: 10.1038/jhg.2015.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vlad G, Chang CC, Colovai AI, Vasilescu ER, Cortesini R, Suciu-Foca N. Membrane and soluble ILT3 are critical to the generation of T suppressor cells and induction of immunological tolerance. Int Rev Immunol. 2010;29:119–132. doi: 10.3109/08830180903281185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gui X, Deng M, Song H, Chen Y, Xie J, Li Z, He L, Huang F, Xu Y, Anami Y, Yu H, Yu C, Li L, Yuan Z, Xu X, Wang Q, Chai Y, Huang T, Shi Y, Tsuchikama K, Liao XC, Xia N, Gao GF, Zhang N, Zhang CC, An Z. Disrupting LILRB4/APOE interaction by an efficacious humanized antibody reverses T-cell suppression and blocks AML development. Cancer Immunol Res. 2019;7:1244–1257. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-19-0036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Babolewska E, Brzezinska-Blaszczyk E. Mast cell inhibitory receptors. Postepy Hig Med Dosw (Online) 2012;66:739–751. doi: 10.5604/17322693.1015039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brown DP, Jones DC, Anderson KJ, Lapaque N, Buerki RA, Trowsdale J, Allen RL. The inhibitory receptor LILRB4 (ILT3) modulates antigen presenting cell phenotype and, along with LILRB2 (ILT4), is upregulated in response to Salmonella infection. BMC Immunol. 2009;10:56. doi: 10.1186/1471-2172-10-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.von Bubnoff D, Wilms H, Scheler M, Brenk M, Koch S, Bieber T. Human myeloid dendritic cells are refractory to tryptophan metabolites. Hum Immunol. 2011;72:791–797. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2011.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhan S, Zheng J, Zhang H, Zhao M, Liu X, Jiang Y, Yang C, Ren L, Liu Z, Hu X. LILRB4 decrease on uDCs exacerbate abnormal pregnancy outcomes following toxoplasma gondii infection. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:588. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.00588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Inui M, Sugahara-Tobinai A, Fujii H, Itoh-Nakadai A, Fukuyama H, Kurosaki T, Ishii T, Harigae H, Takai T. Tolerogenic immunoreceptor ILT3/LILRB4 paradoxically marks pathogenic auto-antibody-producing plasmablasts and plasma cells in non-treated SLE. Int Immunol. 2016;28:597–604. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxw044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu J, Lu CX, Zhang F, Lv W, Liu CY. Expression of ILT3 predicts poor prognosis and is inversely associated with infiltration of CD45RO+T cells in patients with colorectal cancer. Pathol Res Pract. 2018;214:1621–1625. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2018.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang C, Zhu HX, Yao Y, Bian ZH, Zheng YJ, Li L, Moutsopoulos HM, Gershwin ME, Lian ZX. Immune checkpoint molecules. Possible future therapeutic implications in autoimmune diseases. J Autoimmun. 2019;104:102333. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2019.102333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li F, Huang L, Su XL, Gu QH, Hu CP. Inhibition of nuclear factor-kappaB activity enhanced chemosensitivity to cisplatin in human lung adeno-carcinoma A549 cells under chemical hypoxia conditions. Chin Med J (Engl) 2013;126:3276–3282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li QZ, Wei GC, Tao T. Leukocyte immunoglobulin-like receptor B4 (LILRB4) negatively mediates the pathological cardiac hypertrophy by suppressing fibrosis, inflammation and apoptosis via the activation of NF-kappa B signaling. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2019;509:16–23. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.11.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jiang Z, Qin JJ, Zhang YX, Cheng WL, Ji YX, Gong FH, Zhu XY, Zhang Y, She ZG, Huang Z, Li HL. LILRB4 deficiency aggravates the development of atherosclerosis and plaque instability by increasing the macrophage inflammatory response via NF-kappa B signaling. Clin Sci. 2017;131:2275–2288. doi: 10.1042/CS20170198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xu Z, Chang CC, Li M, Zhang QY, Vasilescu EM, D’Agati V, Floratos A, Vlad G, Suciu-Foca N. ILT3.Fc-CD166 interaction induces inactivation of p70 S6 kinase and inhibits tumor cell growth. J Immunol. 2018;200:1207–1219. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1700553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Deng M, Gui X, Kim J, Xie L, Chen W, Li Z, He L, Chen Y, Chen H, Luo W, Lu Z, Xie J, Churchill H, Xu Y, Zhou Z, Wu G, Yu C, John S, Hirayasu K, Nguyen N, Liu X, Huang F, Li L, Deng H, Tang H, Sadek AH, Zhang L, Huang T, Zou Y, Chen B, Zhu H, Arase H, Xia N, Jiang Y, Collins R, You MJ, Homsi J, Unni N, Lewis C, Chen GQ, Fu YX, Liao XC, An Z, Zheng J, Zhang N, Zhang CC. LILRB4 signalling in leukaemia cells mediates T cell suppression and tumour infiltration. Nature. 2018;562:605–609. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0615-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Waschbisch A, Sanderson N, Krumbholz M, Vlad G, Theil D, Schwab S, Maurer M, Derfuss T. Interferon beta and vitamin D synergize to induce immunoregulatory receptors on peripheral blood monocytes of multiple sclerosis patients. PLoS One. 2014;9:e115488. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0115488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fanning LB, Buckley CC, Xing W, Breslow RG, Katz HR. Downregulation of key early events in the mobilization of antigen-bearing dendritic cells by leukocyte immunoglobulin-like Receptor B4 in a mouse model of allergic pulmonary inflammation. PLoS One. 2013;8:e57007. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.de Goeje PL, Bezemer K, Heuvers ME, Dingemans AC, Groen HJ, Smit EF, Hoogsteden HC, Hendriks RW, Aerts JG, Hegmans JP. Immunoglobulin-like transcript 3 is expressed by myeloid-derived suppressor cells and correlates with survival in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Oncoimmunology. 2015;4:e1014242. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2015.1014242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim-Schulze S, Scotto L, Vlad G, Piazza F, Lin H, Liu Z, Cortesini R, Suciu-Foca N. Recombinant Ig-like transcript 3-Fc modulates T cell responses via induction of Th anergy and differentiation of CD8+ T suppressor cells. J Immunol. 2006;176:2790–2798. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.5.2790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chang CC, Zhang QY, Liu Z, Clynes RA, Suciu-Foca N, Vlad G. Downregulation of inflammatory microRNAs by Ig-like transcript 3 is essential for the differentiation of human CD8(+) T suppressor cells. J Immunol. 2012;188:3042–3052. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1102899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xu Z, Ho S, Chang CC, Liu Z, Li M, Vasilescu ER, Clynes RA, Vlad G, Suciu-Foca N. ILT3.Fc inhibits the production of exosomes containing inflammatory microRNA in supernatants of alloactivated T cells. Hum Immunol. 2014;75:756–759. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2014.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Suciu-Foca N, Cortesini R. Central role of ILT3 in the T suppressor cell cascade. Cell Immunol. 2007;248:59–67. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2007.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xu Z, Ho S, Chang CC, Zhang QY, Vasilescu ER, Vlad G, Suciu-Foca N. Molecular and cellular characterization of human CD8 T suppressor cells. Front Immunol. 2016;7:549. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2016.00549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ulges A, Klein M, Reuter S, Gerlitzki B, Hoffmann M, Grebe N, Staudt V, Stergiou N, Bohn T, Bruhl TJ, Muth S, Yurugi H, Rajalingam K, Bellinghausen I, Tuettenberg A, Hahn S, Reissig S, Haben I, Zipp F, Waisman A, Probst HC, Beilhack A, Buchou T, Filhol-Cochet O, Boldyreff B, Breloer M, Jonuleit H, Schild H, Schmitt E, Bopp T. Protein kinase CK2 enables regulatory T cells to suppress excessive TH2 responses in vivo. Nat Immunol. 2015;16:267–275. doi: 10.1038/ni.3083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cousens L, Najafian N, Martin WD, De Groot AS. Tregitope: immunomodulation powerhouse. Hum Immunol. 2014;75:1139–1146. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2014.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bankey PE, Banerjee S, Zucchiatti A, De M, Sleem RW, Lin CF, Miller-Graziano CL, De AK. Cytokine induced expression of programmed death ligands in human neutrophils. Immunol Lett. 2010;129:100–107. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2010.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Breslow RG, Rao JJ, Xing W, Hong DI, Barrett NA, Katz HR. Inhibition of Th2 adaptive immune responses and pulmonary inflammation by leukocyte Ig-like receptor B4 on dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2010;184:1003–1013. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Qiu T, Zhou JQ, Wang TY, Chen ZB, Ma XX, Zhang L, Zou JL. Leukocyte immunoglobulin-like receptor B4 deficiency exacerbates acute lung injury via NF-kappa B signaling in bone marrow-derived macrophages. Bioscience Reports. 2019;39:13. doi: 10.1042/BSR20181888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Katz HR. Inhibition of pathologic inflammation by leukocyte Ig-like receptor B4 and related inhibitory receptors. Immunological Reviews. 2007;217:222–230. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2007.00522.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Banchereau J, Briere F, Caux C, Davoust J, Lebecque S, Liu YT, Pulendran B, Palucka K. Immunobiology of dendritic cells. Ann Rev Immun. 2000;18:767–811. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.18.1.767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kelly A, Fahey R, Fletcher JM, Keogh C, Carroll AG, Siddachari R, Geoghegan J, Hegarty JE, Ryan EJ, O’Farrelly C. CD141(+) myeloid dendritic cells are enriched in healthy human liver. J Hepatol. 2014;60:135–142. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Buckland M, Jago CB, Fazekasova H, Scott K, Tan PH, George AJ, Lechler R, Lombardi G. Aspirin-treated human DCs up-regulate ILT-3 and induce hyporesponsiveness and regulatory activity in responder T cells. Am J Transplant. 2006;6:2046–2059. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01450.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ehser S, Chuang JJ, Kleist C, Sandra-Petrescu F, Iancu M, Wang D, Opelz G, Terness P. Suppressive dendritic cells as a tool for controlling allograft rejection in organ transplantation: promises and difficulties. Hum Immunol. 2008;69:165–173. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2008.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Colletti NJ, Liu H, Gower AC, Alekseyev YO, Arendt CW, Shaw MH. TLR3 signaling promotes the induction of unique human BDCA-3 dendritic cell populations. Front Immunol. 2016;7:88. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2016.00088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Al-Hassi HO, Mann ER, Sanchez B, English NR, Peake ST, Landy J, Man R, Urdaci M, Hart AL, Fernandez-Salazar L, Lee GH, Garrote JA, Arranz E, Margolles A, Stagg AJ, Knight SC, Bernardo D. Altered human gut dendritic cell properties in ulcerative colitis are reversed by Lactobacillus plantarum extracellular encrypted peptide STp. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2014;58:1132–1143. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201300596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sugahara-Tobinai A, Inui M, Metoki T, Watanabe Y, Onuma R, Takai T, Kumaki S. Augmented ILT3/LILRB4 expression of peripheral blood antibody secreting cells in the acute phase of Kawasaki disease. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2019;38:431–438. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000002259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Li Q, Wei G, Tao T. Leukocyte immunoglobulin-like receptor B4 (LILRB4) negatively mediates the pathological cardiac hypertrophy by suppressing fibrosis, inflammation and apoptosis via the activation of NF-kappaB signaling. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2019;509:16–23. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.11.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vlad G, Chang CC, Colovai AI, Berloco P, Cortesini R, Suciu-Foca N. Immunoglobulin-like transcript 3: A crucial regulator of dendritic cell function. Hum Immunol. 2009;70:340–344. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2009.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cohen N, Morisset J, Emilie D. Induction of tolerance by Porphyromonas gingivalis on APCs: a mechanism implicated in periodontal infection. J Dent Res. 2004;83:429–433. doi: 10.1177/154405910408300515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Truong AD, Hong Y, Tran HTT, Dang HV, Nguyen VK, Pham TT, Lillehoj HS, Hong YH. Characterization and functional analyses of novel chicken leukocyte immunoglobulin-like receptor subfamily B members 4 and 5. Poult Sci. 2019;98:6989–7002. doi: 10.3382/ps/pez442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Truong AD, Hong Y, Tran HTT, Dang HV, Nguyen VK, Pham TT, Lillehoj HS, Hong YH. Characterization and functional analyses of novel chicken leukocyte immunoglobulin-like receptor subfamily B members 4 and 5. Poult Sci. 2019;98:6989–7002. doi: 10.3382/ps/pez442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Park M, Raftery MJ, Thomas PS, Geczy CL, Bryant K, Tedla N. Leukocyte immunoglobulin-like receptor B4 regulates key signalling molecules involved in FcgammaRI-mediated clathrin-dependent endocytosis and phagocytosis. Sci Rep. 2016;6:35085. doi: 10.1038/srep35085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chang CC, Liu Z, Vlad G, Qin H, Qiao X, Mancini DM, Marboe CC, Cortesini R, Suciu-Foca N. Ig-like transcript 3 regulates expression of proinflammatory cytokines and migration of activated T cells. J Immunol. 2009;182:5208–5216. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0804048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sugahara-Tobinai A, Inui M, Metoki T, Watanabe Y, Onuma R, Takai T, Kumaki S. Augmented ILT3/LILRB4 expression of peripheral blood antibody secreting cells in the acute-phase of kawasaki disease. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2019;38:431–438. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000002259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fukao S, Haniuda K, Nojima T, Takai T, Kitamura D. gp49B-mediated negative regulation of antibody production by memory and marginal zone B cells. J Immunol. 2014;193:635–644. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1302772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lv W, Duan Q, Wang L, Gong Z, Yang F, Song Y. Expression of B-cell-associated genes in peripheral blood mononuclear cells of patients with symptomatic pulmonary embolism. Mol Med Rep. 2015;11:2299–2305. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2014.2978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wagtmann N, Rojo S, Eichler E, Mohrenweiser H, Long EO. A new human gene complex encoding the killer cell inhibitory receptors and related monocyte/macrophage receptors. Curr Biol. 1997;7:615–618. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(06)00263-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wang LL, Chu DT, Dokun AO, Yokoyama WM. Inducible expression of the gp49B inhibitory receptor on NK cells. J Immunol. 2000;164:5215–5220. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.10.5215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gu X, Laouar A, Wan J, Daheshia M, Lieberman J, Yokoyama WM, Katz HR, Manjunath N. The gp49B1 inhibitory receptor regulates the IFN-gamma responses of T cells and NK cells. J Immunol. 2003;170:4095–4101. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.8.4095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wershil BK, Tsai M, Geissler EN, Zsebo KM, Galli SJ. The rat c-kit ligand, stem cell factor, induces c-kit receptor-dependent mouse mast cell activation in vivo. Evidence that signaling through the c-kit receptor can induce expression of cellular function. J Exp Med. 1992;175:245–255. doi: 10.1084/jem.175.1.245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zoller T, Attaai A, Potru PS, Russ T, Spittau B. Aged mouse cortical microglia display an activation profile suggesting immunotolerogenic functions. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19:706. doi: 10.3390/ijms19030706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kamphuis W, Kooijman L, Schetters S, Orre M, Hol EM. Transcriptional profiling of CD11c-positive microglia accumulating around amyloid plaques in a mouse model for Alzheimer’s disease. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2016;1862:1847–1860. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2016.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.He L, Wang Y, Long Z, Jiang C. Clinical significance of IL-2, IL-10, and TNF-alpha in prostatic secretion of patients with chronic prostatitis. Urology. 2010;75:654–657. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2009.09.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yao CJ, Du W, Chen HB, Xiao S, Wang CH, Fan ZL. Associations of IL-10 gene polymorphisms with acute myeloid leukemia in Hunan, China. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2013;14:2439–2442. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2013.14.4.2439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gregori S, Tomasoni D, Pacciani V, Scirpoli M, Battaglia M, Magnani CF, Hauben E, Roncarolo MG. Differentiation of type 1 T regulatory cells (Tr1) by tolerogenic DC-10 requires the IL-10-dependent ILT4/HLA-G pathway. Blood. 2010;116:935–944. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-07-234872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Svajger U, Obermajer N, Jeras M. Dendritic cells treated with resveratrol during differentiation from monocytes gain substantial tolerogenic properties upon activation. Immunology. 2010;129:525–535. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2009.03205.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Liu J, Lu CX, Zhang F, Lv W, Liu C. Expression of ILT3 predicts poor prognosis and is inversely associated with infiltration of CD45RO+ T cells in patients with colorectal cancer. Pathol Res Pract. 2018;214:1621–1625. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2018.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.LILRB4-signaling mediates T-cell suppression and leukemia infiltration. Cancer Discov. 2018;8:Of19. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Willoughby JE, Kerr JP, Rogel A, Taraban VY, Buchan SL, Johnson PW, Al-Shamkhani A. Differential impact of CD27 and 4-1BB costimulation on effector and memory CD8 T cell generation following peptide immunization. J Immunol. 2014;193:244–251. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1301217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Chen L, Xu Z, Chang C, Ho S, Liu Z, Vlad G, Cortesini R, Clynes RA, Luo Y, Suciu-Foca N. Allospecific CD8 T suppressor cells induced by multiple MLC stimulation or priming in the presence of ILT3.Fc have similar gene expression profiles. Hum Immunol. 2014;75:190–196. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2013.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Vlad G, Suciu-Foca N. Induction of antigen-specific human T suppressor cells by membrane and soluble ILT3. Exp Mol Pathol. 2012;93:294–301. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2012.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Tomic S, Joksimovic B, Bekic M, Vasiljevic M, Milanovic M, Colic M, Vucevic D. Prostaglanin-E2 potentiates the suppressive functions of human mononuclear myeloid-derived suppressor cells and increases their capacity to expand IL-10-producing regulatory T cell subsets. Front Immunol. 2019;10:475. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.00475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hassan G, Afify SM, Nair N, Kumon K, Osman A, Du J, Mansour H, Abu Quora HA, Nawara HM, Satoh A, Zahra MH, Okada N, Seno A, Seno M. Hematopoietic cells derived from cancer stem cells generated from mouse induced pluripotent stem cells. Cancers (Basel) 2019;12:82. doi: 10.3390/cancers12010082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Braza MKE, Gazmen JDN, Yu ET, Nellas RB. Ligand-induced conformational dynamics of a tyramine receptor from sitophilus oryzae. Sci Rep. 2019;9:16275. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-52478-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Mukherjee A, Acharya S, Purkait K, Chakraborty K, Bhattacharjee A, Mukherjee A. Effect of N,N coordination and Ru(II) halide bond in enhancing selective toxicity of a tyramine-based Ru(II) (p-Cymene) complex. Inorg Chem. 2020;59:6581–6594. doi: 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.0c00694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zhang Y, Lu N, Xue Y, Zhang M, Li Y, Si Y, Bian X, Jia Y, Wang Y. Expression of immunoglobulin-like transcript (ILT)2 and ILT3 in human gastric cancer and its clinical significance. Mol Med Rep. 2012;5:910–916. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2012.744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Debes JD, van Tilborg M, Groothuismink ZMA, Hansen BE, Schulze Zur Wiesch J, von Felden J, de Knegt RJ, Boonstra A. Levels of cytokines in serum associate with development of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with HCV infection treated with direct-acting antivirals. Gastroenterology. 2018;154:515–517. e513. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.10.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Colovai AI, Tsao L, Wang S, Lin H, Wang C, Seki T, Fisher JG, Menes M, Bhagat G, Alobeid B, Suciu-Foca N. Expression of inhibitory receptor ILT3 on neoplastic B cells is associated with lymphoid tissue involvement in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Cytometry B Clin Cytom. 2007;72:354–362. doi: 10.1002/cyto.b.20164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Qiu Q, Li M, Yang L, Tang M, Zheng L, Wang F, Qiu H, Liang C, Li N, Yi D, Yi Y, Pan C, Yang S, Chen L, Hu Y. Targeting glutaminase1 and synergizing with clinical drugs achieved more promising antitumor activity on multiple myeloma. Oncotarget. 2019;10:5993–6005. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.27243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Zurli V, Wimmer G, Cattaneo F, Candi V, Cencini E, Gozzetti A, Raspadori D, Campoccia G, Sanseviero F, Bocchia M, Baldari CT, Kabanova A. Ectopic ILT3 controls BCR-dependent activation of Akt in B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2017;130:2006–2017. doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-03-775858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Cao L, Xia X, Kong Y, Jia F, Yuan B, Li R, Li Q, Wang Y, Cui M, Dai Z, Zheng H, Christensen J, Zhou Y, Wu X. Deregulation of tumor suppressive ASXL1 - PTEN/AKT axis in myeloid malignancies. J Mol Cell Biol. 2020:mjaa011. doi: 10.1093/jmcb/mjaa011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Schmid AS, Tintor D, Neri D. Novel antibody-cytokine fusion proteins featuring granulocyte-colony stimulating factor, interleukin-3 and interleukin-4 as payloads. J Biotechnol. 2018;271:29–36. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2018.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Dobrowolska H, Gill KZ, Serban G, Ivan E, Li Q, Qiao P, Suciu-Foca N, Savage D, Alobeid B, Bhagat G, Colovai AI. Expression of immune inhibitory receptor ILT3 in acute myeloid leukemia with monocytic differentiation. Cytometry B Clin Cytom. 2013;84:21–29. doi: 10.1002/cyto.b.21050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Fournier B, Balducci E, Duployez N, Clappier E, Cuccuini W, Arfeuille C, Caye-Eude A, Delabesse E, Bottollier-Lemallaz Colomb E, Nebral K, Chretien ML, Derrieux C, Cabannes-Hamy A, Dumezy F, Etancelin P, Fenneteau O, Frayfer J, Gourmel A, Loosveld M, Michel G, Nadal N, Penther D, Tigaud I, Fournier E, Reismuller B, Attarbaschi A, Lafage-Pochitaloff M, Baruchel A. B-ALL with t(5;14)(q31;q32); IGH-IL3 rearrangement and eosinophilia: a comprehensive analysis of a peculiar IGH-rearranged B-ALL. Front Oncol. 2019;9:1374. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2019.01374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.John S, Chen H, Deng M, Gui X, Wu G, Chen W, Li Z, Zhang N, An Z, Zhang CC. A novel anti-lilrb4 car-t cell for the treatment of monocytic AML. Mol Ther. 2018;26:2487–2495. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2018.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Vlad G, King J, Chang CC, Liu Z, Friedman RA, Torkamani AA, Suciu-Foca N. Gene profile analysis of CD8(+) ILT3-Fc induced T suppressor cells. Hum Immunol. 2011;72:107–114. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2010.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Nakase K, Kita K, Katayama N. IL-2/IL-3 interplay mediates growth of CD25 positive acute myeloid leukemia cells. Med Hypotheses. 2018;115:5–7. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2018.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Sadras T, Kok CH, Perugini M, Ramshaw HS, D’Andrea RJ. miR-155 as a potential target of IL-3 signaling in primary AML cells. Leuk Res. 2017;57:57–59. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2017.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Faulkner J, Jiang P, Farris D, Walker R, Dai Z. CRISPR/CAS9-mediated knockout of Abi1 inhibits p185(Bcr-Abl)-induced leukemogenesis and signal transduction to ERK and PI3K/Akt pathways. J Hematol Oncol. 2020;13:34. doi: 10.1186/s13045-020-00867-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Li Z, Deng M, Huang F, Jin C, Sun S, Chen H, Liu X, He L, Sadek AH, Zhang CC. LILRB4 ITIMs mediate the T cell suppression and infiltration of acute myeloid leukemia cells. Cell Mol Immunol. 2020;17:272–282. doi: 10.1038/s41423-019-0321-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kobayashi K, Mizuta S, Yamane N, Ueno H, Yoshida K, Kato I, Umeda K, Hiramatsu H, Suehiro M, Maihara T, Usami I, Shiraishi Y, Chiba K, Miyano S, Adachi S, Ogawa S, Kiyokawa N, Heike T. Paraneoplastic hypereosinophilic syndrome associated with IL3-IgH positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2019;66:e27449. doi: 10.1002/pbc.27449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Gui X, Deng M, Song H, Chen Y, Xie J, Li Z, He L, Huang F, Xu Y, Anami Y, Yu H, Yu C, Li L, Yuan Z, Xu X, Wang Q, Chai Y, Huang T, Shi Y, Tsuchikama K, Liao XC, Xia N, Gao GF, Zhang N, Zhang CC, An Z. Disrupting LILRB4/APOE interaction by an efficacious humanized antibody reverses T-cell suppression and blocks AML development. Cancer Immunol Res. 2019;7:1244–1257. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-19-0036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Guy DG, Uy GL. Bispecific antibodies for the treatment of acute myeloid leukemia. Curr Hematol Malig Rep. 2018;13:417–425. doi: 10.1007/s11899-018-0472-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Wang M, Wu H, Duan M, Yang Y, Wang G, Che F, Liu B, He W, Li Q, Zhang L. SS30, a novel thioaptamer targeting CD123, inhibits the growth of acute myeloid leukemia cells. Life Sci. 2019;232:116663. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2019.116663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Stahl M, Goldberg AD. Immune checkpoint inhibitors in acute myeloid leukemia: novel combinations and therapeutic targets. Curr Oncol Rep. 2019;21:37. doi: 10.1007/s11912-019-0781-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Chien KS, Class CA, Montalban-Bravo G, Wei Y, Sasaki K, Naqvi K, Ganan-Gomez I, Yang H, Soltysiak KA, Kanagal-Shamanna R, Do KA, Kantarjian HM, Garcia-Manero G. LILRB4 expression in chronic myelomonocytic leukemia and myelodysplastic syndrome based on response to hypomethylating agents. Leuk Lymphoma. 2020;61:1493–1499. doi: 10.1080/10428194.2020.1723014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Bellavia D, Raimondo S, Calabrese G, Forte S, Cristaldi M, Patinella A, Memeo L, Manno M, Raccosta S, Diana P, Cirrincione G, Giavaresi G, Monteleone F, Fontana S, De Leo G, Alessandro R. Interleukin 3- receptor targeted exosomes inhibit in vitro and in vivo Chronic Myelogenous Leukemia cell growth. Theranostics. 2017;7:1333–1345. doi: 10.7150/thno.17092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Li Z, Zhao M, Li T, Zheng J, Liu X, Jiang Y, Zhang H, Hu X. Decidual macrophage functional polarization during abnormal pregnancy due to toxoplasma gondii: role for LILRB4. Front Immunol. 2017;8:1013. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Wu CH, Lee TH, Yang SF, Tsao HM, Chang YJ, Chou CH, Lee MS. Interleukin-3 polymorphism is associated with miscarriage of fresh in vitro fertilization cycles. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16:995. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16060995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Butcher MJ, Filipowicz AR, Waseem TC, McGary CM, Crow KJ, Magilnick N, Boldin M, Lundberg PS, Galkina EV. Atherosclerosis-driven treg plasticity results in formation of a dysfunctional subset of plastic IFNgamma+ Th1/Tregs. Circ Res. 2016;119:1190–1203. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.309764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Fujita K, Fukuda M, Fukui H, Horie M, Endoh S, Uchida K, Shichiri M, Morimoto Y, Ogami A, Iwahashi H. Intratracheal instillation of single-wall carbon nanotubes in the rat lung induces time-dependent changes in gene expression. Nanotoxicology. 2015;9:290–301. doi: 10.3109/17435390.2014.921737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Renner K, Metz S, Metzger AM, Neumayer S, Schmidbauer K, Talke Y, Buchtler S, Halbritter D, Mack M. Expression of IL-3 receptors and impact of IL-3 on human T and B cells. Cell Immunol. 2018;334:49–60. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2018.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Anzai A, Mindur JE, Halle L, Sano S, Choi JL, He S, McAlpine CS, Chan CT, Kahles F, Valet C, Fenn AM, Nairz M, Rattik S, Iwamoto Y, Fairweather D, Walsh K, Libby P, Nahrendorf M, Swirski FK. Self-reactive CD4(+) IL-3(+) T cells amplify autoimmune inflammation in myocarditis by inciting monocyte chemotaxis. J Exp Med. 2019;216:369–383. doi: 10.1084/jem.20180722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Inui M, Hirota S, Hirano K, Fujii H, Sugahara-Tobinai A, Ishii T, Harigae H, Takai T. Human CD43+ B cells are closely related not only to memory B cells phenotypically but also to plasmablasts developmentally in healthy individuals. Int Immunol. 2015;27:345–355. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxv009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Jensen MA, Patterson KC, Kumar AA, Kumabe M, Franek BS, Niewold TB. Functional genetic polymorphisms in ILT3 are associated with decreased surface expression on dendritic cells and increased serum cytokines in lupus patients. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72:596–601. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Zhou H, Li N, Yuan Y, Jin YG, Wu Q, Yan L, Bian ZY, Deng W, Shen DF, Li H, Tang QZ. Leukocyte immunoglobulin-like receptor B4 protects against cardiac hypertrophy via SHP-2-dependent inhibition of the NF-kappaB pathway. J Mol Med (Berl) 2020;98:691–705. doi: 10.1007/s00109-020-01896-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Quanzheng L, Gongchang W, Tao T. Corrigendum to “Leukocyte immunoglobulin-like receptor B4 (LILRB4) negatively mediates the pathological cardiac hypertrophy by suppressing fibrosis, inflammation and apoptosis via the activation of NF-kappaB signaling” [BIOCHEM BIOPH RES CO volume 509 (issue 1) (29 January 2019) pages 16-23] . Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2020;521:548. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2019.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Jiang Z, Qin JJ, Zhang Y, Cheng WL, Ji YX, Gong FH, Zhu XY, Zhang Y, She ZG, Huang Z, Li H. LILRB4 deficiency aggravates the development of atherosclerosis and plaque instability by increasing the macrophage inflammatory response via NF-kappaB signaling. Clin Sci (Lond) 2017;131:2275–2288. doi: 10.1042/CS20170198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Lu Y, Jiang Z, Dai H, Miao R, Shu J, Gu H, Liu X, Huang Z, Yang G, Chen AF, Yuan H, Li Y, Cai J. Hepatic leukocyte immunoglobulin-like receptor B4 (LILRB4) attenuates nonalcoholic fatty liver disease via SHP1-TRAF6 pathway. Hepatology. 2018;67:1303–1319. doi: 10.1002/hep.29633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Qiu T, Zhou J, Wang T, Chen Z, Ma X, Zhang L, Zou J. Leukocyte immunoglobulin-like receptor B4 deficiency exacerbates acute lung injury via NF-kappaB signaling in bone marrow-derived macrophages. Biosci Rep. 2019;39:BSR20181888. doi: 10.1042/BSR20181888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Esnault S, Leet JP, Johansson MW, Barretto KT, Fichtinger PS, Fogerty FJ, Bernau K, Mathur SK, Mosher DF, Sandbo N, Jarjour NN. Eosinophil cytolysis on immunoglobulin G is associated with microtubule formation and suppression of rho-associated protein kinase signalling. Clin Exp Allergy. 2020;50:198–212. doi: 10.1111/cea.13538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Zhao G, Luo X, Han X, Liu Z. Combining bioinformatics and biological detection to identify novel biomarkers for diagnosis and prognosis of pulmonary tuberculosis. Saudi Med J. 2020;41:351–360. doi: 10.15537/smj.2020.4.24989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Khaliullin TO, Yanamala N, Newman MS, Kisin ER, Fatkhutdinova LM, Shvedova AA. Comparative analysis of lung and blood transcriptomes in mice exposed to multi-walled carbon nanotubes. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2020;390:114898. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2020.114898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Coindre S, Tchitchek N, Alaoui L, Vaslin B, Bourgeois C, Goujard C, Lecuroux C, Bruhns P, Le Grand R, Beignon AS, Lambotte O, Favier B. Mass cytometry analysis reveals complex cell-state modifications of blood myeloid cells during HIV infection. Front Immunol. 2019;10:2677. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.02677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Borges IN, Resende CB, Vieira ELM, Silva J, Andrade MVM, Souza AJ, Badaro E, Carneiro RM, Teixeira AL Jr, Nobre V. Role of interleukin-3 as a prognostic marker in septic patients. Rev Bras Ter Intensiva. 2018;30:443–452. doi: 10.5935/0103-507X.20180064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.La Manna MP, Orlando V, Li Donni P, Sireci G, Di Carlo P, Cascio A, Dieli F, Caccamo N. Identification of plasma biomarkers for discrimination between tuberculosis infection/disease and pulmonary non tuberculosis disease. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0192664. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0192664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Li X, Yuan X, Wang C. The clinical value of IL-3, IL-4, IL-12p70, IL17A, IFN-gamma, MIP-1beta, NLR, P-selectin, and TNF-alpha in differentiating bloodstream infections caused by gram-negative, gram-positive bacteria and fungi in hospitalized patients: an observational study. Medicine (Baltimore) 2019;98:e17315. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000017315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Xiu MH, Wang D, Chen S, Du XD, Chen DC, Chen N, Wang YC, Yin G, Zhang Y, Tan YL, Cho RY, Soares JC, Zhang XY. Interleukin-3, symptoms and cognitive deficits in first-episode drug-naive and chronic medicated schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2018;263:147–153. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2018.02.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Fu YY, Zhang T, Xiu MH, Tang W, Han M, Yun LT, Chen DC, Chen S, Tan SP, Soares JC, Tang WJ, Zhang XY. Altered serum levels of interleukin-3 in first-episode drug-naive and chronic medicated schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2016;176:196–200. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2016.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Stewart N, Simpson S Jr, van der Mei I, Ponsonby AL, Blizzard L, Dwyer T, Pittas F, Eyles D, Ko P, Taylor BV. Interferon-beta and serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D interact to modulate relapse risk in MS. Neurology. 2012;79:254–260. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31825fded9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Penna G, Roncari A, Amuchastegui S, Daniel KC, Berti E, Colonna M, Adorini L. Expression of the inhibitory receptor ILT3 on dendritic cells is dispensable for induction of CD4+ Foxp3+ regulatory T cells by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. Blood. 2005;106:3490–3497. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-05-2044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]