Abstract

Background

Living with Parkinson disease (PD) is complicated by an unpredictable disease course which can delay planning for future needs. This study explores patient and care partner needs related to future planning using a palliative care framework with physical, psychological, social, cultural, end-of-life, and ethical aspects of care in PD to guide analysis.

Methods

Secondary analysis of patient and care partner interviews from a randomized clinical trial comparing interdisciplinary outpatient palliative care versus standard care for individuals with PD and care partners in an academic setting. Sixty participants were interviewed (30 patients and 30 care partners) about needs related to future planning. Team-based thematic analysis was used to identify key themes.

Results

Many care partners and patients living with PD described a desire for information about what to expect and how to plan for the future. Participants posed multiple questions about PD progression and devised the metaphor of a “roadmap” as a guide for decision making and planning. When exploring the concept of a PD roadmap, five themes emerged: (I) desire for a comprehensive tool for future planning, such as a roadmap; (II) care partner preferences for specific future planning; (III) PD-related life changes as opportunity for future planning and decision-making; (IV) cues from family, peers, and medical professionals about “location” on the roadmap; and (V) opportunities and challenges to integrating a PD roadmap into patient-centered care.

Conclusions

Patients and care partners described key needs related to future planning that can inform a comprehensive roadmap to assist with education, communication, and decision making. A roadmap tool can promote individualized anticipatory guidance and multidimensional shared decision-making discussions between patients, care partners, and the healthcare team related to PD progression.

Keywords: Caregiver, decision-making, palliative care, Parkinson disease (PD), qualitative

Introduction

Parkinson disease (PD) has significant impact on patient and care partner quality of life, function, and overall well-being. Core palliative care issues, such as those related to support for families and care partners, attention to spiritual wellbeing, discussions about prognosis, and planning for progressive disability, are not systematically addressed (1–3). A patient and family’s understanding of serious or chronic illnesses, including how the disease is changing over time, can affect how patients and care partners navigate disease management, quality of life preferences, and future planning (4). Given that PD is the 14th leading cause of death in the US and is associated with significant symptom burden and dementia, there is a clear need for clinical tools that help patients and families throughout the disease trajectory (5,6).

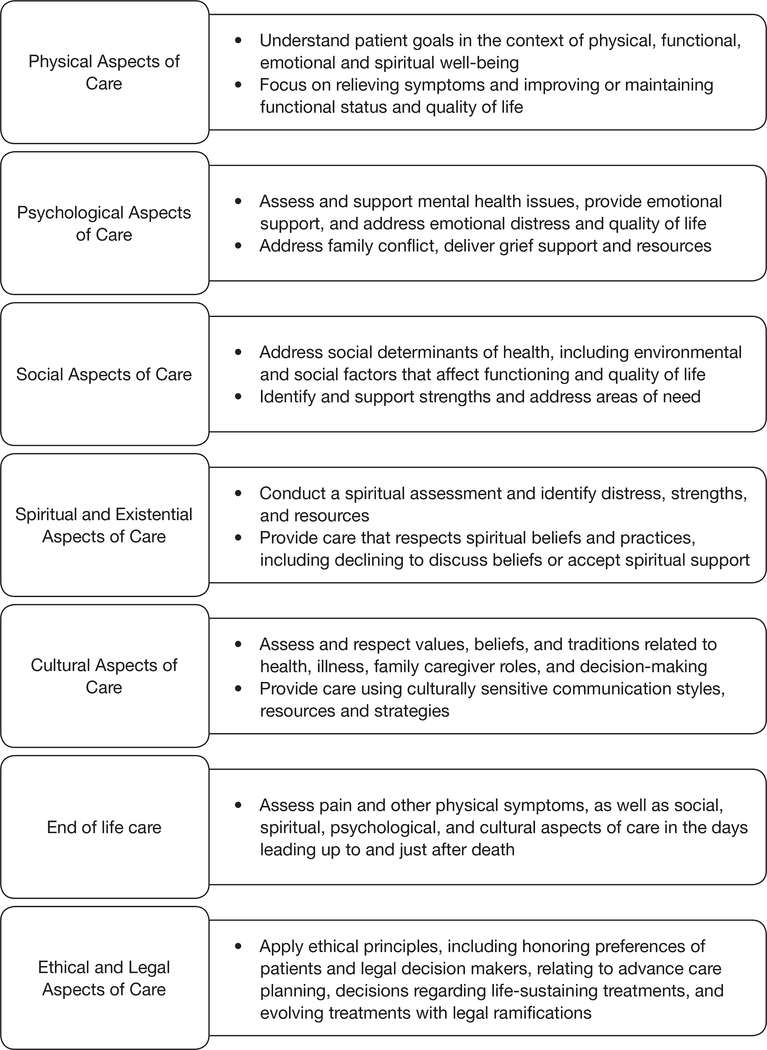

Palliative care approaches can address the individual needs of patients and care partners related to living with serious illness (7). The National Consensus Project Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care (NCP Guidelines) describes seven domains of palliative care which are highlighted in Figure 1 (8). While recent studies have described the opportunity to integrate palliative care into routine PD neurological care (9–11), there is a need to more specifically understand patient and care partner preferences for multidimensional and comprehensive future planning across the PD illness trajectory, and the extent to which patient and care partner needs are effectively addressed by exploring the palliative care domains.

Figure 1.

Brief descriptions of key domains of quality palliative care, adapted from the National Consensus Project Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care (8).

PD, a progressive neurodegenerative disease, has limited evidence-based or patient and family co-created educational materials to provide anticipatory guidance about expectations as the disease progresses (12,13). The purposes of patient educational materials are to facilitate education, shared decision making, and communication (14). A persistent message of PD clinical care, educational resources, and support groups is that each person is unique, and that no two illness trajectories are alike. While this may be true, it is not helpful to individuals trying to prepare for the future. Existing information sources are generally very extensive and difficult for patients and families to use. Currently, there are no comprehensive future planning tools for use in clinical practice that utilize a multidimensional palliative care approach for PD.

The lack of anticipatory guidance for illness trajectories may be a source of caregiver burden. A recent study of care partners of persons with dementia found that uncertainty around the future was one of three burden factors, along with direct impact of caregiving and frustration or embarrassment (15). Therefore, in this current study, we engaged a Parkinson Disease Patient and Family Advisory Council as research stakeholders (16), and together identified the need for education about the PD illness trajectory. Our primary objective was to explore patient and care partner perspectives on anticipatory guidance for what to expect and how to plan for the future as the illness progresses. We used a qualitative descriptive approach to conduct an in-depth exploration of the concept of a “roadmap”, a metaphor that resonated with patients and care partners within a large randomized clinical trial of palliative care for PD. After describing the importance of a roadmap for comprehensive future planning in PD, this study highlights patient and care partner perspectives related to “What should be on the roadmap? Where am I/we on the roadmap? Who can I ask for support?”, framed by the National Consensus Project Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care.

Methods

Design

This qualitative descriptive study is a secondary analysis of a large, multi-site randomized clinical trial of interdisciplinary outpatient neuropalliative care compared to standard neurological care for individuals with PD and care partners, which has been described in detail (17,18). The current study draws from semi-structured interviews with 30 PD patients and 30 care partners at 12 months since enrollment in the trial. The research was conducted among 210 patients with symptomatic PD, and care partners if present, who were all recruited from the University of Colorado Hospital Movement Disorders Clinic (Aurora, Colorado, USA), Kaye Edmonton Clinic at the University of Alberta (Edmonton, Alberta, Canada), and University of California San Francisco Parkinson Disease Supportive Care Clinic (San Francisco, California, USA). Patients and their care partners, when identified, were randomized to usual care, including a primary care provider and neurologist, or to palliative care, including an outpatient interdisciplinary palliative care team consisting of a neurologist with palliative care experience, a nurse, a social worker, and a chaplain. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at each site. All participants provided written informed consent. Participants were not compensated for interviews but did receive reimbursement for participating in the RCT. The clinical trial identifier is NCT02533921.

Participants

Patients were included if they were fluent in English, over age 40, and met UK Brain Bank criteria for a diagnosis of probable PD (19). Patients were at high risk for poor outcomes based on the Palliative Care Needs Assessment Tool (20), modified for PD. Care partners were identified by asking the patient who assists them the most with their PD. Interviews were conducted between September, 2017, and March, 2018. During this period, 81 patients and 56 care partners had reached the study 12-month time point. The research team planned a goal of 60 interviews from 137 participants available at the time of our qualitative study to ensure maximum variation from all three study locations, both study arms, all genders, and both respondent types (patient and care partner). Potential interview participants were also chosen to have diverse perspectives such as patients who did and did not have a care partner; care partners of persons with dementia; and participants (both patients and care partners) who are affected by early vs more advanced PD based on Hoehn and Yahr staging. Purposeful sampling was guided by input from site investigators (21,22), who defined whether patients or care partners were no longer able to participate in the interview because it could be potentially burdensome or they had significant executive problems, or because they had moved or had died. Patients or care partners were interviewed separately.

Research question and data collection

Our main study question explored the desire for help or guidance related to comprehensive future planning needs related to living with PD as a patient or care partner. We developed a semi-structured interview guide (see Supplement 1) that was revised iteratively with input from the Parkinson Disease Patient and Family Advisory Council and a multidisciplinary scientific advisory board with expertise in movement disorders and palliative care. Interview topics included future planning, planning in the context of potential cognitive changes or dementia, communication about the future with spouses/care partners/family members, and perceptions of illness progression. As the metaphor of a roadmap emerged, it was re-contextualized in subsequent interviews and explored in-depth. To enable participants to describe their future planning needs and preferences in an open-ended fashion, interviewers did not specifically probe for the seven palliative care domains from the NCP Guidelines (physical, psychological, social, spiritual, cultural, end-of-life, and ethical/legal care). Interviews lasted up to 2 hours, were digitally recorded, and were conducted by research team members who were not part of the participants’ clinical team. Interviews were digitally recorded and professionally transcribed. Respondents provided demographic information both on themselves and their associated study partner (except for patients without a care partner). Less than 5% of demographic data is missing.

Data analysis

This analysis uses an iterative, team-based, inductive and deductive approach to identify key themes (23). Transcripts were de-identified with the exception of participant type (patient or care partner), study site, and study arm (palliative care or standard care) and read inductively individually by each team member. We defined and agreed upon a codebook, and three authors each coded roughly one-third of the data (with double coding to enhance reliability of code use over 25% of transcripts). Team members met regularly to discuss emerging themes, reach consensus, and organize meaningful content and relationships between codes into thematic schemes which reflected participant perspectives and experiences (24). The deductive approach focused on conceptualizing and organizing key concepts or topics for a PD-specific comprehensive future planning tool (a “roadmap”) using the NCP Guidelines as a framework. We tracked analytic decisions on emerging themes throughout analysis. We conducted triangulation with the larger multidisciplinary team and the Parkinson Disease Patient and Family Advisory Council to increase validity, as a measure of quality in qualitative research (25,26). Informational saturation was reached prior to reaching the goal of 60 participants, but all interviews were thoroughly analyzed (24,27). We used Atlas.ti (Version 7.5.18) software for data management.

Results

Thirty patients and thirty care partners were interviewed, evenly split across both standard care and palliative care arms and proportionate across all three study sites (Table 1). Most care partners were female (77%) and the majority of patients were male (63%). Most interviewees were Caucasian, with an average current age of 67 and average age at diagnosis of 57 years old.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics

| Characteristic | Patients (n=30), n [%] | Care partners (n=30), n [%] |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years [SD] | 66 [8] | 68 [7] |

| Age at time of PD diagnosis, years [SD] | 57 [8.4] | N/A |

| Female sex | 11 [37] | 23 [77] |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| White | 27 [90] | 27 [90] |

| Black | 1 [3] | 0 [0] |

| Asian | 2 [7] | 2 [7] |

| Hispanic | 0 [0] | 0 [0] |

| Site | ||

| University of Alberta | 11 [37] | 12 [40] |

| University of Colorado | 11 [37] | 9 [30] |

| University of California San Francisco | 8 [27] | 9 [30] |

| Study arm | ||

| Palliative care | 14 [47] | 20 [67] |

| Standard care | 16 [53] | 10 [33] |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 25 [83] | 28 [93] |

| Single | 1 [3] | 2 [6.7] |

| Divorced/widowed | 4 [13] | 0 [0] |

| Education | ||

| High school or less | 2 [7] | 5 [17] |

| Bachelor degree or some college | 12 [40] | 14 [47] |

| Post graduate | 16 [53] | 11 [37] |

| Income | ||

| Under $49,000 | 4 [16] | N/A |

| $50,000–$99,999 | 15 [60] | 1 [50] |

| More than $100,000 | 6 [24] | 1 [50] |

| Disease duration† (months, SD) | 110 [77] | N/A |

| Received deep brain stimulation surgery† | 4 [13] | 5 [17] |

| Hoehn and Yahr† | ||

| Level I | 10 [33] | 8 [27] |

| Level II | 11 [37] | 9 [30] |

| Level III | 5 [17] | 6 [20] |

| Level IV | 1 [3] | 4 [13] |

| Level V | 1 [3] | 3 [10] |

| Montreal Cognitive Assessment, mean (SD)† | 26 [3.2] | 24 [4.7] |

| Care partner type | ||

| Spouse or partner | 19 [63] | 27 [90] |

| Child or other | 3 [10] | 3 [10] |

| No care partner | 8 [27] | N/A |

| Care partner lives in same household as patient | 21 [95] | 28 [93] |

| Involved in support groups | 17 [57] | 19 [63] |

| Duration of caregiving [SD], months | N/A | 80 [46] |

includes patients with this characteristic, and care partners of patients with this characteristic. This sample is also described in a related study (28).

Patients and care partners described the metaphor of a PD roadmap that could help with anticipating future needs and raising appropriate questions for discussion among patients, care partners, and the healthcare team. Five key themes emerged from participants: (I) desire for a comprehensive tool for future planning, such as a roadmap, (II) care partner preferences for specific future planning, (III) PD-related life changes as opportunity for future planning and decision-making, (IV) cues from family, peers, and medical professionals about “location” on the roadmap, and (V) opportunities and challenges to integrating a PD roadmap into patient-centered care.

Theme 1—desire for a comprehensive tool for future planning, such as a roadmap

When initially asked about future planning related to living with PD, patients and care partners recognized the difficulty of knowing what questions to ask or what information is important. In early interviews, as participants considered what would be important to them related to living with PD, the metaphor of a roadmap emerged and was explored in-depth. When considering the future, patients and care partners had several questions related to how their PD would change over time and how quickly it would change (i.e., “speed” of PD illness trajectory). These questions reflected a desire for information that would address their personal experiences compared to an expected PD trajectory and/or the experiences of others. In their own words, patients identified the concept of a roadmap: “A roadmap, or even things we should be looking at in end stage, would be helpful” (standard care). Another patient in standard care described specific questions a roadmap might address, stating,

“[A roadmap would show] where the ‘rest stops’ are, [because] not all symptoms are the same. Where would the [rest stops] be? How much longer is it going to take it for me to get there? Don’t we have stuff that we can look forward to? That’s what I’m hoping for so that maybe we get control over it. How else would you know?”

Theme 2—care partner preferences for specific future planning

Care partners also desired a comprehensive tool to help navigate future planning. In many cases, care partners were able to specifically describe their need for practical guidance to navigate the PD journey. A care partner from the palliative care arm described,

“Knowledge is power, so you need to know how to prepare yourself if you can. One of the things that I would like to know more about is the caregiving later. I was talking to a social worker that said there are real problems down the road financially if you have to go into assisted living, and I need to know more about that to prepare financially.”

Table 2 shows questions that both patients and care partners from both standard care and the palliative care arm had about the future. Common questions included what to expect, how to gauge PD-related severity, how to plan for future needs, and who to ask for support. In some cases, questions from care partners incorporated concrete options (e.g., assisted living facility vs. nursing home) and related considerations or limitations (e.g., finances) because they were already thinking far down the road, while patients often felt like they were trying to adjust to current physical and cognitive changes due to PD. When patients were open to discussing future planning, they could identify the change or challenge that would need to be addressed but sometimes were not able to articulate multiple options and decisions.

Table 2.

Frequent questions from patients and care partners related to Parkinson disease and future planning

| Topic | Examples of questions about the future asked by patients |

|---|---|

| What to expect due to PD | What am I going to need in the future? (patient, standard care) |

| What is going to be coming down the pike? (care partner, palliative care) | |

| What’s next? And then what’s next, and then what’s next? (care partner, palliative care) | |

| How to gauge PD-related severity | What’s early, late and latest... how do you know? (care partner, palliative care) |

| Sometimes you think things are worse and maybe they aren’t, right? What are the trigger points? How do you know that all of a sudden, we’ve entered a new phase without somebody who is experienced saying to you this is different from last year, isn’t it? How do you benchmark it? (care partner, palliative care) | |

| How quickly is PD changing | Are we going faster or are we going slower than the predicted speed? (patient, standard care) |

| How to plan for future needs | When the disease progresses to a certain point, do I have a plan to handle it? (care partner, standard care) |

| How can I prepare? How do I know what he is going to need? Where is he headed? (care partner, palliative care) | |

| Who to ask for support | Who would provide that kind of support for [my care partner]? (patient, standard care) |

Theme 3—PD-related life changes as opportunity for future planning and decision-making

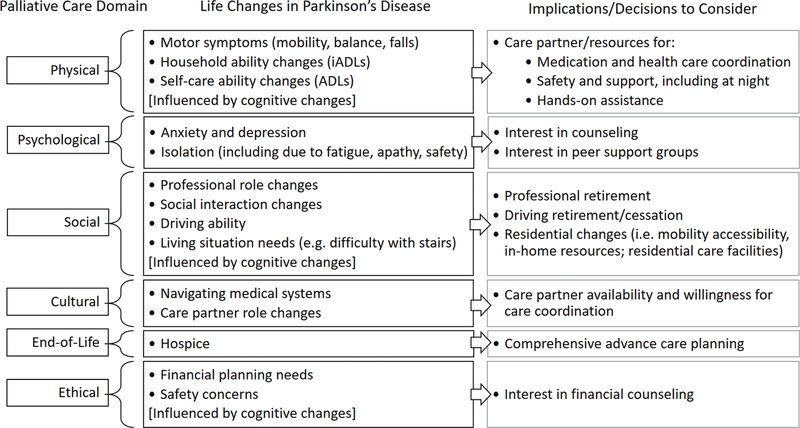

For the question, “What is on the roadmap?”, patients and care partners identified potential “road markers” or important topics on the roadmap which could metaphorically signal PD-related life changes and a need to make certain decisions. Using the analogy of a roadmap, the road markers could be a sign that they have entered new territory to adjust to, or a sign of a fork in the road where a decision(s) needs to be made. Some life changes were identified by the patient, but more often, changes were noted by the care partner. Grouped according to the NCP Guidelines palliative care domains, Figure 2 lists common issues and concerns described by patients and care partners along their PD illness trajectory. Table S1 provides exemplary quotations from patients and care partners related to the PD-related life changes.

Figure 2.

Grouping of patient and care partner identified life changes in Parkinson disease and implications or decisions to consider, by palliative care domains from the National Consensus Project Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care.

Aligned with the NCP Guidelines, the two most prominent, necessary domains identified for comprehensive future planning related to ‘anticipated changes in physical care’ and ‘social aspects of life’. Physical care examples included a desire to know how motor symptoms affected mobility, such as the ability to climb stairs or cause falls, as well as concerns broadly related to the need for assistance due to increasing disability. Future or progressive limitations in instrumental activities of daily living (e.g., medications) and self-care abilities (e.g., bathing, dressing, eating) were issues that patients and care partners wanted anticipatory guidance for. Patients and care partners described understanding their disease course by using markers to identify life changes related to how they would function in daily activities. For example, a patient in the palliative care arm said, “They said my disease will get worse and I will need walkers and wheelchairs. I’m concerned about that being a burden on my wife.” Similarly, a care partner in standard care also identified road markers, “I can see that he might need some care with bathing and dressing, and also if I need to do some errands or if I want to go on a trip, we might need to have some in-home care or friends come in… it would depend on the level of progression of his disease.”

As patients and care partners identified these PD-related physical changes, they described decisions and needs for helping navigate their current situation. Anticipating or experiencing limitations in daily life activities often led to concerns about where they could find more practical assistance or whether they should consider moving to a residential care facility. Managing potential changes in living arrangements was a frequent concern, and included discussions of preferences related to remaining at home, moving to a more accessible home, an assisted living facility or nursing home, and timing of moving. One care partner in the palliative care arm described the big decisions they were making about residential changes, in the midst of uncertainty about whether the patient’s functional status warranted a change, saying,

“What does everybody else do? How do you know when it’s time to say you need somebody in full-time evening and daytime, and when do we need to consider assisted living or nursing home? I don’t know if there are any trigger points for that because he’s not there yet I don’t think.”

Another prominent palliative care domain for future planning is social aspects of life (Figure 2). Patients and care partners described life changes related to their PD experience including professional role changes, social interaction changes, decreased driving abilities, and living situation needs. Many of these changes were influenced by underlying cognitive impairment, which affected quality of life and frequently affected the care partner’s role in PD care planning. With respect to the other palliative care domains, patients and care partners described needs for guidance around life changes that related to ethical and legal issues (e.g., financial planning needs, safety concerns) and cultural aspects of care (e.g., navigating medical systems and care partner role changes), as described in detail in Supplemental Table 1.

Theme 4—cues from others about “location” on the roadmap

To answer the question “Where am I on the roadmap?”, patients and care partners located themselves along the roadmap by comparing their experience to that of peers/support group members, input from healthcare professionals, and other medical changes (medications; objective assessments). Both patients and care partners used peers in support groups as indicators for either what is to come or what may already be progressing quickly:

“They say, ‘you’re doing quite well’, and I think I am compared to others who have 20 years under their belt. There were a lot of guys in our support group who are now in nursing homes because they’ve crossed the line and can’t take care of themselves. I’m still able to do a lot of that myself. In fact, I’m going to stop driving just this year.” (Patient in standard care).

Perceptions of how peers have progressed along the disease course strongly centered on social aspects of care, including seeing peers moving to assisted living, still able to continue driving, and developing dementia. Other topics like mortality and life expectancy remained unclear and difficult:

“Three other couples from our support group are pretty much in the same situation… we’re all in the advanced stages of it… we’re all dealing with dementia, but none of us are equipped to deal with death. Nobody has talked about it until last November- almost 14 ½ years of having Parkinson’s before anybody talked about death.” (Care partner in palliative care).

Interactions with healthcare professionals also influenced where participants perceived themselves to be on the roadmap. Some alluded to a dissonance between cues from healthcare professionals and personal beliefs; when one care partner in the palliative arm was advised to consider assisted living, she described poignantly how this “professional roadmap” did not match her own personal roadmap of where she believed her loved one to be:

“That was the roadmap, for me to put him in a nursing home. That was the professional opinion... and it just didn’t feel right to me. I don’t know that there’s too much value to thinking ahead too far.”

Tracking medications or clinical and cognitive assessments were also methods used to gauge disease progression. Care partners described monitoring changes in the type and quantity of medications as a clue of progression, yet they also described a desire for clarity surrounding what these changes to medications actually meant for disease progression. One care partner in the palliative care arm described the desire for objective measurements for PD progression, such as neuropsychological testing:

“I’d like a little more guidance about where we’re at and where we’re going. They do the MOCA [Montreal Cognitive Assessment] and they tell us the results but it’s just a screening test. It’d be really nice if there was a psychological or a neuropsychological assessment. I know it’s expensive, but it would be a snapshot of where the person is at and where they’re going. Sometimes you think things are worse and maybe they aren’t, right? Or, it would be really nice to have these sorts of milestones. You sense things are changing but you don’t always know for sure until you have an assessment or the doctor talks about it.”

Theme 5—integrating roadmaps into patient-centered PD care

To address questions about “Who can I ask for support?”, patients and care partners offered suggestions on how to integrate future planning into clinical care for PD-affected patients and care partners. Patients and care partners desired for clinicians to assess readiness to engage in future planning in a tailored and honest fashion that met patients and families where they were:

“It may have to be disclosed in bits and pieces, because I think he doesn’t really want to know. When I suggested we go to the support group, he really didn’t want to see what people were like in more advanced stages – it would depress him, the different stages in disease. I do wonder, how bad will it be? What do we have to do at the latest stage when there’s more disability?” (Care partner, palliative care arm).

Importantly, some had contradicting views, as this patient in the palliative care arm said: “I think it would have been helpful to have been given some idea of what was to come. It wouldn’t have been such a surprise—shock, actually—if I had known what to expect.” Another care partner in the palliative care arm noted the importance of addressing discrepancies in understandings of how future changes affect quality of life:

“I have asked, how can I prepare? How do I know what he is going to need, where is he headed? It was like ‘well, everybody is different.’ That’s not particularly helpful. I need to know what it is I’m facing and the notion that it’s different for everybody is understandable, but not helpful. There [has to be] a generalization; maybe nine out of a hundred people would need this, maybe 50 out of a 100 people would need this, we find that after five years people start needing walkers and diapers and you know, whatever. It’s just where the road goes.”

In the context of this large outpatient neuropalliative care study, participants also identified strengths to having an interdisciplinary team-based approach, where nurses, social workers, and chaplains often also helped foster/facilitate honest discussions about the future over multiple visits.

Patients and care partners told us how a roadmap to facilitate discussions about the future was desired but would also be emotionally charged. For example, a care partner in palliative care said, “I feel like I have both an advantage and a disadvantage… I sort of know what to expect, but it makes me sadder now than it would if I didn’t know until later.” A patient in standard care said, “You can maybe find out too much and then get depressed. You kind of want to know but you don’t want to know.” Each of these statements demonstrates the sensitivity of having discussions about the future with PD, and the delicacy with which these discussions should be addressed by healthcare professionals.

Some patients and care partners did not wish to have a roadmap. One care partner explained: “I’m not trying to go ten years down the road, and I’m trying to look at what we can do now and enjoy every day now and not be all frantic about what we might have to do in 10 years’ time” (standard care). Others described how comparisons to peers can have a potentially negative or detrimental effect:

“That’s one reason I don’t want to see Parkinson people, because everybody’s story is a little bit different. During the course you run into these different situations, and I’m just not interested in jumping to the end to find out. I’m not going to sit down with some guy telling me exactly what’s going to happen two years from now based on where I’m at.” (Patient in standard care).

Discussion

Patients and care partners living with PD expressed a desire for a comprehensive tool to facilitate anticipatory guidance discussions with their clinicians about future care planning. Using the National Consensus Project Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care to frame our analysis, patients and care partners emphasized physical, social, ethical/legal, emotional and cultural domains of care as they considered their questions and needs for the future. In this qualitative study, both patients and care partners described their own priorities for key PD-related life changes and implications for future planning and decision making. These priorities align with and go beyond existing medical approaches like a palliative care assessment, a comprehensive geriatric assessment, and advance care planning and goals of care discussions.

This is the first study to describe PD patient and care partner needs for future care planning through the lens of key palliative care domains. Collectively, the findings begin to suggest how researchers, patient and care partner advisors, and end-users (e.g., patients, care partners, healthcare teams) could conceptualize, refine and test a PD-specific roadmap. Given the potential for high symptom burden and distress related to multiple aspects of living with PD, future studies should formally develop a roadmap as a comprehensive shared decision-making tool that incorporates palliative care domains. The potential outcomes of an effective roadmap include patient, care partner and dyadic outcomes such as improved quality of life, receipt of needed functional assistance, relationship satisfaction and goal-concordant end-of-life care, as well as decreased care partner burden, financial burden, and time spent away from their preferred setting. Pragmatic clinical trials should understand how to implement an effective roadmap tool into clinical practice.

Findings from care partners highlighted the importance of care partner desire for information and support. Our data emphasized that care partners actively considered more than physical changes for PD patients; they consider the “whole person” and changes related to housing, driving, function, and finances. While care partners and patients asked about different aspects of road markers, they saw the value of the topics on the roadmap as opportunity to begin or continue future planning conversations as a common point of reference. Further input from patients and care partners in the design of a roadmap should identify whether there are specific variations or adaptations for unique patient or care partner versions.

Clinicians should facilitate honest, tailored conversations with patients and care partners that openly address progression, lifespan, and mortality with PD. Table 3 provides examples of clinical communication approaches on integrating anticipatory guidance about future changes and planning into clinical care. Directly discussing expectations earlier in the disease course may impact decisions and improve quality of life throughout time as PD progresses. Clinicians should also consider discussing future implications for PD, including shorter- or longer-term expectations, with patient and care partners/family when conducting clinic-based assessments such as cognitive screening (e.g., Montreal Cognitive Assessment). Our findings support participants’ desire for more discussion about the interpretation of the assessments and what their results may indicate about the speed and nature of PD progression.

Table 3.

Suggestions for clinician approaches to assessing patient and care partner needs related to comprehensive future planning

| Purpose and assessment | Example communication approaches for clinicians |

|---|---|

| Introduce and normalize the concept of a roadmap | We know that many people often have questions about where they are in their Parkinson disease and what comes next, or what to expect and plan for. While I don’t have a crystal ball, I do have a roadmap that may be helpful in thinking about the future |

| Assess patient or care partner’s perspective of PD illness trajectory, and current needs | What are you noticing about your Parkinson disease? What do you think it means in terms of where you are on the roadmap? |

| Assess readiness for more information | Who would you like to talk about this? Would both of you like to be involved in these conversations? Is it ok to talk about this in detail? |

| Assess preferences for amount and type of information, including about prognosis | How much information would you like to discuss about what to expect next, or in the future? |

| Offer to discuss the issue of ‘speed’ | As we think about the future, we can discuss how fast things are likely to change. We can talk about how much time there is to make decisions |

| Offer to discuss specific PD-related changes or assessments | Here are some of the things we are looking for that signal that things might be changing. (e.g., functional changes; cognitive changes or objective assessment changes; falls; safety concerns; weight loss, swallowing issues) |

| Assess care partner’s current role or involvement | In relation to the (patient), has your involvement changed? Can you describe what you’re doing? |

| Assess current sources of support (such as care partner, family, support group, community organizations) | Can you tell me about who you can ask for help or support? |

Consistent with core principles of palliative care and shared decision making, clinicians need to accurately recognize when patients or care partners are ready to discuss the future or anticipatory guidance. As PD progresses, some patients and care partners may find it difficult to discuss the future, or may struggle with the tension of wanting to know and not wanting to know. Clinicians can explore resistance or reluctance to the topics, offer support, and encourage patients and families to talk honestly. Team-based approaches with chaplains and social workers can help address and support these communications and multiple aspects of palliative care needs. This study suggests that patients and care partners who participated in neuropalliative care seemed to approach anticipatory guidance conversations with more readiness or awareness than standard care participants. Additionally, care partners might desire a more detailed discussion or independent clinical visit, if possible, within the healthcare system.

This study has several limitations. Although this study is closely grounded in patient and care partner experiences, their perspectives are highly personalized and each participant is not aware of the full range of PD phenotypes. An ideal shared decision-making tool would incorporate balanced and diverse input from patients, care partners, and experienced interdisciplinary healthcare team members. While attempts were made to ease the burden of the phone interview, PD-related fatigue, dysarthria, and low speech volume affected PD patients and audio quality and interview clarity for some participants. A few PD patients were able to participate with the assistance of a care partner who repeated the patient’s responses. Finally, while this qualitative study is large and aimed to include as much variation in patient and care partner perspectives as possible, the study population includes predominantly white and highly educated individuals. A large majority of care partners were women. These clinical trial participants also may not be representative of persons not participating in clinical research. As a result, our understanding of the cultural aspects of care is particularly limited by the relative lack of diversity of our cohort and warrants further specific exploration.

In conclusion, patients and especially their care partners desire information for comprehensive future planning related to PD illness progression. Patients and care partners have multiple palliative care needs that they would like information about and would like the opportunity to discuss PD-related life changes. An evidence-based tool, such as a roadmap, could provide desired information to facilitate shared decision making by patients, care partners and healthcare teams, ultimately helping to improve quality of life and the experience of living with PD.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was possible with the assistance of our Parkinson Disease Patient and Family Advisory Council stakeholders: Fran Berry, Kirk Hall, Linda Hall, Carol Johnson, Patrick Maley, and Malenna Sumrall. We also thank Laura Palmer, Etta Abaca, Francis Cheung, Jana Guenther, Claire Koljack, Chihyung Park, Stefan Sillau, and Raisa Syed for their assistance as part of the larger study team. We thank Elizabeth Staton for expert assistance with manuscript preparation and review. Finally, special thanks to Dr. Betty Ferrell, of the Palliative Care Research Cooperative Caregiver Core for her expertise.

Funding: This work was supported by a Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) Award (HIS-1408-20134); the Palliative Care Research Cooperative Group funded by National Institute of Nursing Research (U24NR014637); and the National Institute on Aging (K76AG054782).

Conflicts of Interest: A Hall reports receiving reimbursement for participating as a member of the PCORI-funded Parkinson Disease Patient and Family Advisory Council. All other authors have no relevant conflicts of interest to disclose.

Footnotes

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at each site. All participants provided written informed consent.

Disclaimer: The statements presented in this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI), its Board of Governors or Methodology Committee. The contents do not represent the views of Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States Government.

References

- 1.Goy ER, Carter JH, Ganzini L. Needs and experiences of caregivers for family members dying with Parkinson disease. J Palliat Care 2008;24:69–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Holloway RG, Gramling R, Kelly AG. Estimating and communicating prognosis in advanced neurologic disease. Neurology 2013;80:764–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schrag A, Hovris A, Morley D, et al. Caregiver-burden in Parkinson’s disease is closely associated with psychiatric symptoms, falls, and disability. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2006;12:35–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bonsaksen T, Lerdal A, Fagermoen MS. Trajectories of illness perceptions in persons with chronic illness: An explorative longitudinal study. J Health Psychol 2015;20:942–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Minino AM, Murphy SL. Death in the United States, 2010. NCHS Data Brief 2012:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reid WG, Hely MA, Morris JG, et al. Dementia in Parkinson’s disease: a 20-year neuropsychological study (Sydney Multicentre Study). J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2011;82:1033–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Katz M, Goto Y, Kluger BM, et al. Top Ten Tips Palliative Care Clinicians Should Know About Parkinson’s Disease and Related Disorders. J Palliat Med 2018;21:1507–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ferrell BR, Twaddle ML, Melnick A, et al. National Consensus Project Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care Guidelines, 4th Edition. J Palliat Med 2018. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boersma I, Jones J, Carter J, et al. Parkinson disease patients’ perspectives on palliative care needs: What are they telling us? Neurol Clin Pract 2016;6:209–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miyasaki JM, Kluger B. Palliative care for Parkinson’s disease: has the time come? Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep 2015;15:26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kluger BM, Shattuck J, Berk J, et al. Defining Palliative Care Needs in Parkinson’s Disease. Mov Disord Clin Pract 2018;6:125–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grosset KA, Grosset DG. Patient-perceived involvement and satisfaction in Parkinson’s disease: effect on therapy decisions and quality of life. Mov Disord 2005;20:616–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shimbo T, Goto M, Morimoto T, et al. Association between patient education and health-related quality of life in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Qual Life Res 2004;13:81–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Butterworth K, Allam O, Gray A, et al. Providing confusion: the need for education not information in chronic care. Health Informatics J 2012;18:111–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smith KJ, George C, Ferreira N. Factors emerging from the “Zarit Burden Interview” and predictive variables in a UK sample of caregivers for people with dementia - CORRIGENDUM. Int Psychogeriatr 2019;31:437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hall K, Sumrall M, Thelen G, et al. Parkinson’s Disease Foundation sponsored “Palliative Care, Parkinson’s Disease” Patient Advisory Council. Palliative care for Parkinson’s disease: suggestions from a council of patient and carepartners. NPJ Parkinsons Dis 2017;3:16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kluger BM, Katz M, Galifianakis N, et al. Does outpatient palliative care improve patient-centered outcomes in Parkinson’s disease: Rationale, design, and implementation of a pragmatic comparative effectiveness trial. Contemp Clin Trials 2019;79:28–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Giles S, Miyasaki J. Palliative stage Parkinson’s disease: patient and family experiences of health-care services. Palliat Med 2009;23:120–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hughes AJ, Daniel SE, Kilford L, et al. Accuracy of clinical diagnosis of idiopathic Parkinson’s disease: a clinico-pathological study of 100 cases. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1992;55:181–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Waller A, Girgis A, Currow D, et al. Development of the palliative care needs assessment tool (PC-NAT) for use by multi-disciplinary health professionals. Palliat Med 2008;22:956–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Coyne IT. Sampling in qualitative research. Purposeful and theoretical sampling; merging or clear boundaries? J Adv Nurs 1997;26:623–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Trotter RT 2nd. Qualitative research sample design and sample size: resolving and unresolved issues and inferential imperatives. Prev Med 2012;55:398–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three Approaches to Qualitative Content Analysis. Qual Health Res 2005;15:1277–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morse JM. Critical Analysis of Strategies for Determining Rigor in Qualitative Inquiry. Qual Health Res 2015;25:1212–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hammersley M Assessing Quality in Qualitative Research. ESRC TLRP seminar series: Quality in Educational Research; 2005. July. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carter N, Bryant-Lukosius D, DiCenso A, et al. The use of triangulation in qualitative research. Oncol Nurs Forum 2014;41:545–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Creswell JW, Poth CN. Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches. Thousand Oaks: Sage publications; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lum HD, Jordan SR, Brungardt A, et al. Framing advance care planning in Parkinson disease: Patient and care partner perspectives. Neurology 2019;92:e2571–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.