Abstract

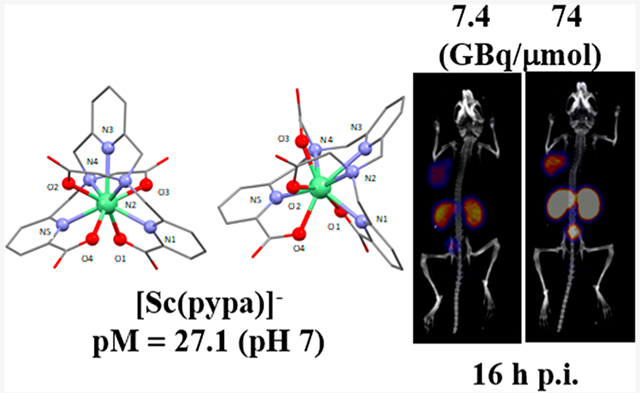

44Sc is an attractive positron-emitting radionuclide for PET imaging; herein, a new complex of the Sc3+ ion with nonmacrocyclic chelator H4pypa was synthesized and characterized with high-resolution electrospray-ionization mass spectrometry (HR-ESI-MS), as well as different nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopic techniques (1H, 13C, 1H−13C HSQC, 1H−13C HMBC, COSY, and NOESY). In aqueous solution (pH = 7), [Sc(pypa)]− presented two isomeric forms, the structures of which were predicted using density functional theory (DFT) calculation with a small energy difference of 22.4 kJ/mol, explaining their coexistence. [Sc(pypa)]− was found to have superior thermodynamic stability (pM = 27.1) compared to [Sc(AAZTA)]− (24.7) and [Sc(DOTA)]− (23.9). In radiolabeling, [44Sc][Sc(pypa)]− formed efficiently at RT in 15 min over a range of pH (2−5.5), resulting in a complex that is highly stable (>99%) in mouse serum over at least six half-lives of scandium-44. Similar labeling efficiency was observed with the PSMA (prostate-specific membrane antigen)-targeting H4pypa-C7-PSMA617 at pH = 5.5 (RT, 15 min), confirming negligible disturbance from the bifunctionalization on scandium-44 scavenging. Moreover, the kinetic inertness of the radiocomplex was proved in vivo. Surprisingly, the molar activity was found to have profound influence on the pharmacokinetics of the radiotracers where lower molar activity drastically reduced the background accumulations, particularly, kidney, and thus, yielded a much higher tumor-to-background contrast.

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Decay properties of radionuclides can be harnessed for cancer diagnosis and therapy. In nuclear medicine, there are two principal imaging techniques—Single Photon Emission Computed Tomography (SPECT) and Positron Emission Tomography (PET). Compared to SPECT imaging, PET generally has higher sensitivity and spatial resolution (2−4 mm vs 6−8 mm).1 In PET imaging, the location of the radiotracer in the body is identified through the coincident detection of two back-to-back (~180°) γ-rays (511 keV each) produced upon the annihilation between the positron (β+) emitted and the electron (e−) encountered.2−4 The travel distance of the positron before the annihilation event correlates to the positron energy, thereby determining the image resolution.4

An ideal PET isotope should possess low positron energy, a high positron branching ratio, and a long enough half-life for radiolabeling and probing biological events.5 Unlike the more “organic radionuclides” (carbon-11, nitrogen-13, oxygen-15, fluorine-18), which are mostly limited by short half-lives,5 a much broader decay spectrum can be found in radiometals such as yttrium-86 (t1/2 = 14.7 h), copper-61/64 (t1/2 = 12.7 h/3.33 h), scandium-44 (t1/2 = 3.97 h), zirconium-89 (t1/2 = 78.5 h), gallium-68 (t1/2 = 1.13 h), etc.6,7 Their much longer half-lives allow for production in distant cyclotrons, enabling the expansion of PET diagnosis beyond large medical centers. Gallium-68 is one of the most used clinical positron emitters due to its high positron branching ratio (Iβ+ = 89%) and the widely available germinium-68/gallium-68 generator,8−10 but the application is restricted by its rather short 68 min half-life, plus the breakthrough of germanium-68 and other metal-ion impurities present in the eluate complicates the separation and radiolabeling procedures.5,11,12 In this regard, scandium-44 offers several advantages, including its almost quadrupled half-life, higher positron fraction (Iβ+ = 94.3%) with lower energy (Eβ+avg) = 632 keV, compared to gallium-68 (Eβ+avg = 830 keV), thereby favoring spatial resolution.11,13 Furthermore, a human PET/CT imaging study conducted by Singh et al. using [44Sc][Sc(DOTATOC)] proved prolonged imaging up to 23.5 h postinjection feasible,14 while 68Ga-labeled tracers are generally limited beyond 4 h.15,16 Hence, scandium-44 is considered a better surrogate marker for long-lived therapeutic isotopes such as lutetium-177 and scandium-47 in a pretherapeutic dosimetry study.17−19 Currently, scandium-44 can be produced via either a titanium-44/scandium-44 generator or cyclotron irradiation of a calcium-44 target (44Ca(p,n)44Sc).20,21

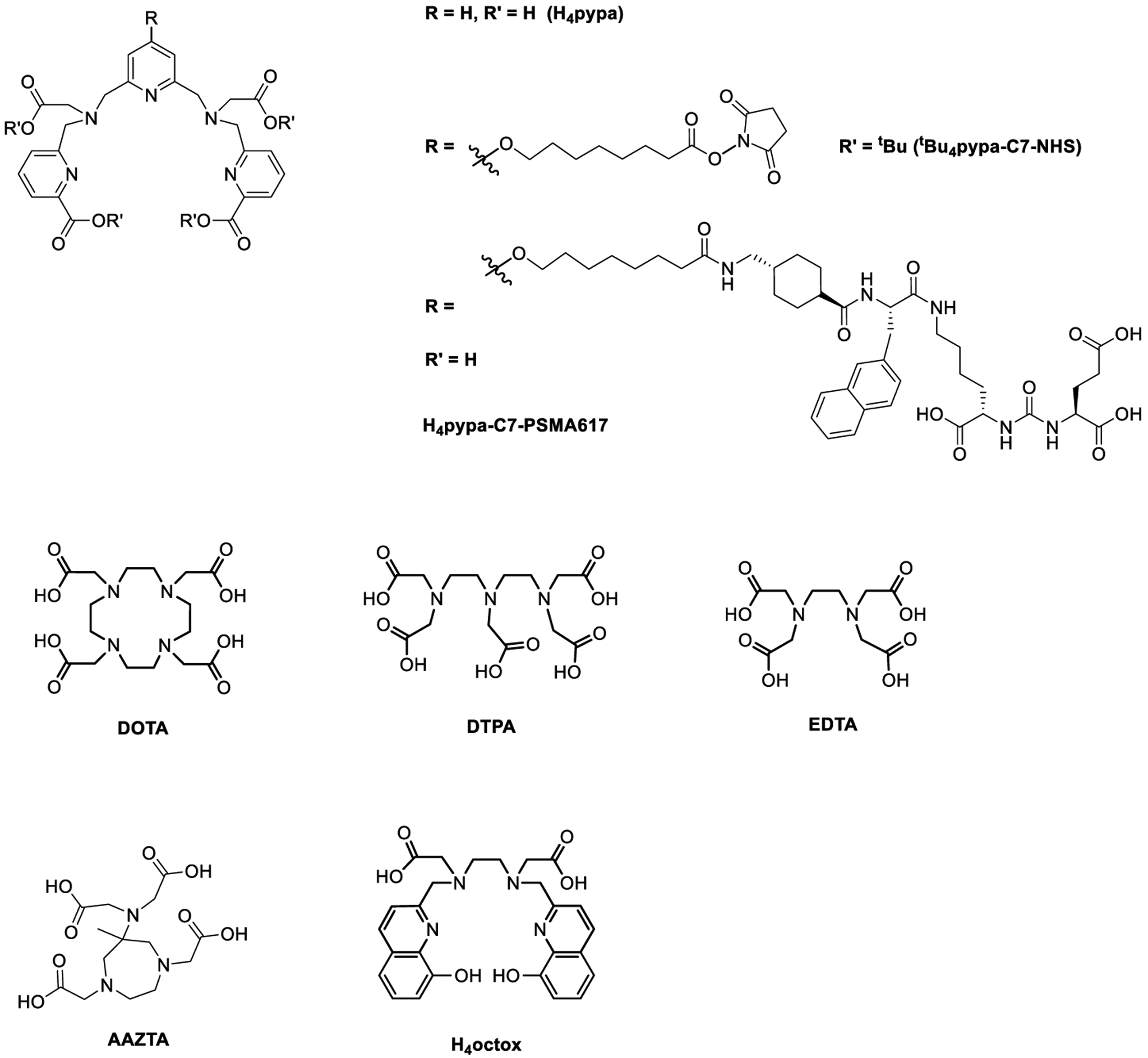

Incorporating a metallic radionuclide into a radiopharmaceutical entails a bifunctional chelator that can secure the radiometal ion. To date, macrocyclic DOTA (1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecane-1,4,7,10-tetraacetic acid; Chart 1) and its derivatives are the workhorses for complexation of many radiometal ions including scandium-44, but the harsh radiolabeling conditions (>95 °C) are a drawback.7,11 Therefore, alternatives are sought (Chart 1), including acyclic DTPA (diethylenetriamine-pentaacetic acid) and mesocyclic AAZTA (6-[bis(hydroxycarbonyl-methyl)amino]-1,4-bis-(hydroxycarbonyl methyl)-6-methylperhydro-1,4-diaze-pine).18,22 AAZTA offers radiolabeling at room temperature, but it is heavily time-dependent (~80% radiochemical yield in 30 min).22

Chart 1.

Chemical Structures of the Discussed Chelators

Considering the above-mentioned factors, we set out to explore the potential of H4pypa for scandium-44 as a chelating agent for pharmaceutical purposes. H4pypa previously displayed excellent affinity for lutetium-177 (β−, γ, t1/2 ~ 6.64 days);23 therefore, its chelation with scandium-44 can pave the way for this “matched pair” in the theranostic applications. Herein, studies of H4pypa and the conjugate of glutamate-urea-lysine-based PSMA-targeting pharmacophore, H4pypa-C7-PSMA617 (Chart 1), for prostate-cancer (PCa) targeting are reported with respect to its suitability for Sc3+ ion. The targeting vector was selected for its excellent affinity and selectivity to PSMA, which overexpresses in nearly all stages of PCa, the most common cancer in men in the United States.24−28 Syntheses of H4pypa and H4pypa-C7-PSMA617 were reported in our first report.23 Herein, the nonradioactive [Sc(pypa)]− complex is reported and characterized with HR-ESI-MS and different NMR spectroscopic techniques. Variable-temperature 1H NMR spectroscopy revealed the coexistence of two structural isomers, the geometries of which were estimated with density functional theory (DFT) calculation. Spectrophotometric and potentiometric titrations were conducted to determine the thermodynamic stability of the complex while radiolabeling experiments were performed to evaluate the complexation efficiency in extremely dilute solutions. To assess the biological stability of the complex and the impacts of injected molar activity on the pharmacokinetics, biodistribution studies were performed on PSMA-xenograft-bearing mice using tracers with two different apparent molar activities.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Metal Complexation and Characterization.

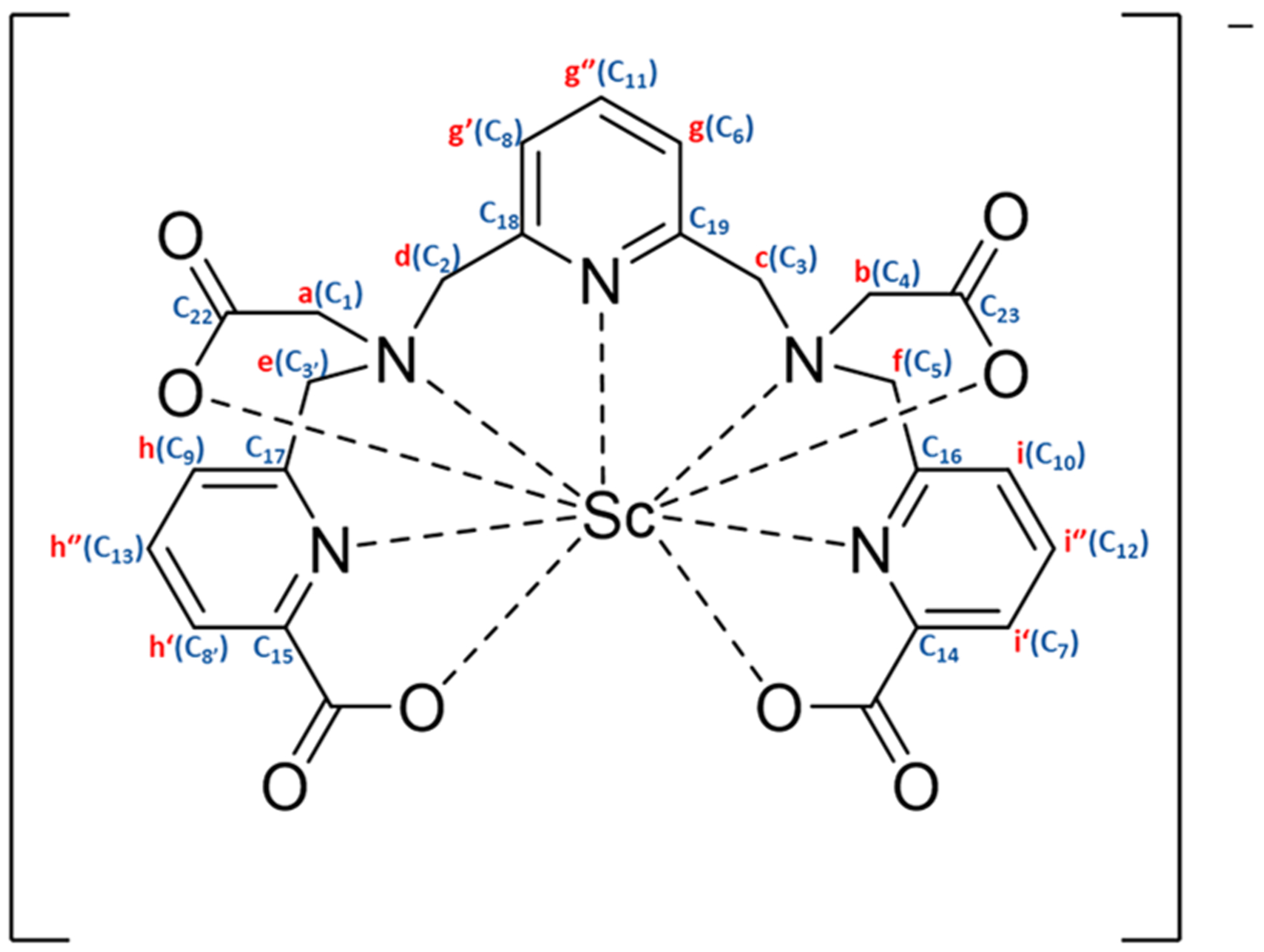

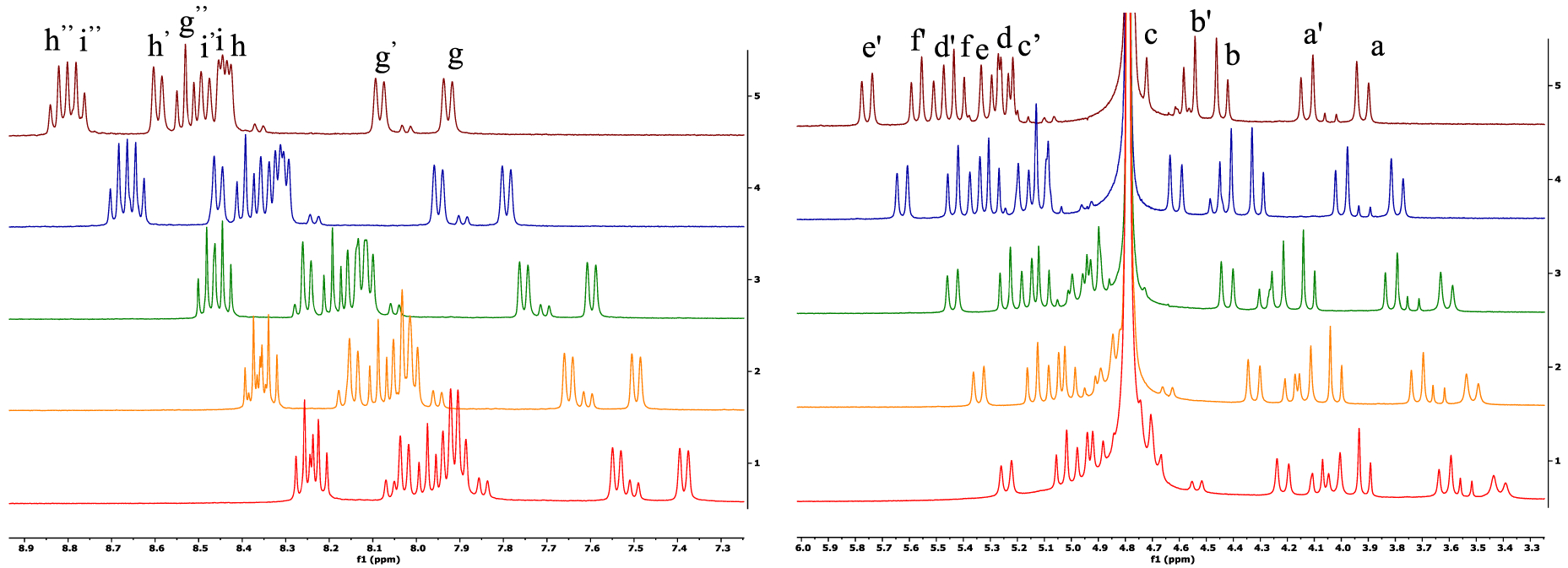

The complex of H4pypa (Figure 1) with Sc3+ was fully characterized with NMR spectroscopy and HR-ESI-MS. 1H NMR spectra revealed the coexistence of two geometric isomers of the complex (major and minor) which interconverted in a temperature-dependent manner (Figure 2). As shown in the VT-NMR spectra, from 25 °C to 85 °C, some minor isomers converted to the major one (Figure 2), and the conversion was reversible as the temperature cooled down. The interconversion could be seen from the significantly reduced signal intensity of the minor 1H peaks, and therefore, the corresponding correlations in both 1H−13C HSQC (Figures S3 and S10) and COSY (Figures S6 and S11) spectra became invisible at higher temperatures. Although the characterization of the minor isomer by NMR was impossible due to excessive overlapping of the 1H signals, the major isomer could be identified via 1H−13C HSQC and HMBC, as well as COSY and NOESY at 70 °C, at which temperature the intervening cross-peaks from the minor isomer were minimized (Figures S1−S7). The assignment of 1H and 13C signals is depicted in Figure 1, and the labels can be referred to in Figure 1 (1H, a−i) and Figures S2B,C (13C, 1−23).

Figure 1.

[Sc(pypa)]−1H and 13C NMR assignments (see Figures 2 and S2A–C for labels).

Figure 2.

Sc-pypa variable temperature 1H NMR downfield (left) and upfield (right) spectra (400 MHz, D2O, pH 7; 25, 35, 45, 65, 85 °C from bottom to top). Please refer to Figure S1A for the full 1H NMR spectrum.

The asymmetry in the Sc-pypa complex could be seen from the twelve aliphatic and nine aromatic 1H−13C couplings in the HSQC (Figure S3), as well as the six pairs of diastereotropic methylene-H atoms (Figure S6). The J3 coupling between the ortho-H (g (g′), i (i′), h (h′)) and the neighboring para-H (g″, i″, h″; Figure S6) confirmed the three distinct pyridyl groups in the complex. With reference to the chemical shift, g″ (triplet) was assigned to the para-H in the central pyridine while two overlapping triplets (i″ and h″) belonged to those in the picolinate arms (Figure S1C). Ha,a′ and Hb,b′ were assigned to the methylene groups in the two acetate arms due to the strong interaction with the adjacent CC=O (C22 and C23, respectively, Figure S4D). CHa,a′ (C1) correlated to He′ and Hd′ (Figure S5B), while Hd′ also coupled to CHg′ (C8; Figure S5C) and the quaternary C18 (Figure S5E). Therefore, Hd,d′ and He,e′ were close to Ha,a′ and were assigned to the methylene groups adjacent to the central pyridine and the pyridine in the picolinate arm, respectively (Figure 1). Similarly, Hc,c′ correlated to both CHb,b′ (C4) and CHf,f′ (C5; Figure S5B), while Hf spatially coupled to Hi (Figure S7B) and Hc,c′ correlated to CHg (C6; Figure S5C). Thus, Hc,c′ and Hf,f′ were assigned to the methylene groups neighboring the middle pyridine and that in the second picolinate arm, respectively (Figure 1). The assignment could be further confirmed by the 1H−13C(quaternary) interactions (i.e., Hc,c′ and Hg,g″ with C19; Hf′ and Hi,i″ with C16; Hd′ and Hg′,g″ with C18; He′ and Hh″ with C17; Figure S5D,E). The only missing assignments are the carbonyl carbons (C20 and C21) in both picolinate arms due to the absence of observable correlation with the adjacent H (Figure S5A). Additionally, the fluxionality in the [Sc(pypa)]− complex was reflected by the exchange of the pendent arms in space (between two acetate arms and between two picolinate arms), indicated by the strong exchange cross-peaks (blue) in the NOESY spectrum at 70 °C (a and b′, a′ and b, c and d′, f and e′, f′ and e, g and g′, h″ and i″, h′ and i′, Figure S7). The spatial exchange of the chelating arms suggested that the fluxionality possibly involved the chelate ring opening and reclosing. The broader 1H peaks at room temperature, particularly in the aliphatic region, indicated a slower chelating-arm exchange, which was further confirmed by the absence of the exchange cross-peaks (blue) in the NOESY spectrum at room temperature (Figure S12). The intrinsic fluxional behavior of the [Sc(pypa)]− complex can be justified by the small size of the Sc3+ ion (ionic radii = 0.75–0.87 Å, coordination number = 6–8) relative to the 9-coordinating binding cavity of H4pypa.29 Nonetheless, the splitting of the methylene-1H signals upon coordination implied a 9-coordinated [Sc(pypa)]−.

Coexisting in equilibrium, two [Sc(pypa)]− isomers could not be distinguished with HPLC (Figure S14), perhaps due to the similar chemical properties. Admittedly, the isomerism could be a concern for radiopharmaceutical applications; however, it should not be a limitation since more important considerations in this regard would be the biological stability and properties of the [Sc(pypa)]− complex in both isomeric forms, which can only be evaluated by biodistribution studies. Furthermore, the biological properties of a metal complex are heavily dependent on the conjugated targeting vector. For example, when conjugated to a larger targeting vector such as an antibody or antibody fragment, the influence of the metal-chelate on the biodistributions would be significantly reduced, as long as the complex is stable in vivo. As a result, despite the coexistence of both isomers at room temperature, it is still important to evaluate the in vivo behavior of the [Sc(pypa)]− complex as a bioconjugate.

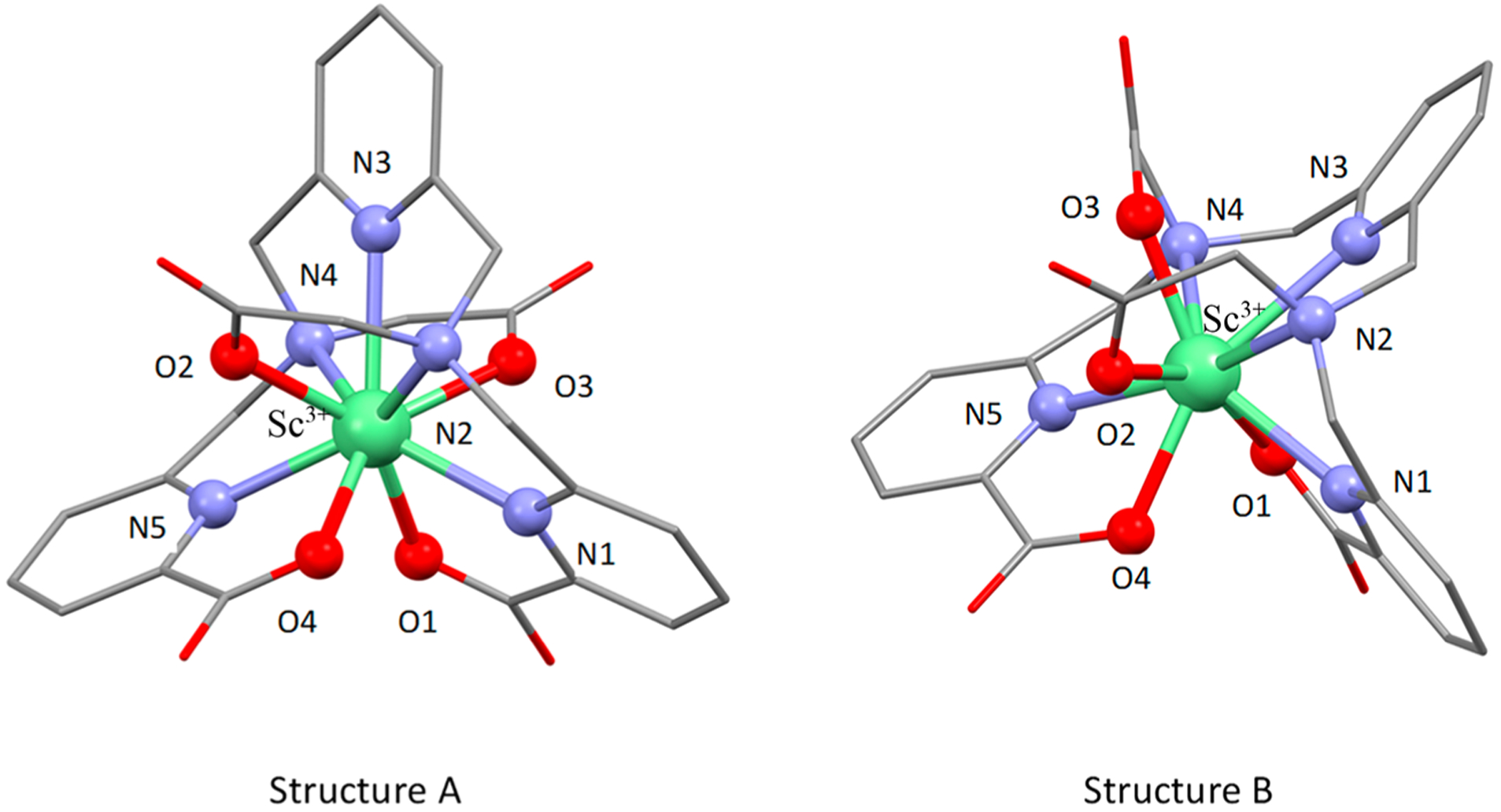

DFT Calculations.

DFT calculations were carried out to study the structure of the [Sc(pypa)]− anion in solution. Two stable isomeric structures, A and B (Figure 3), were identified, featuring different bond conformations around the pyridyl backbone. In structure B, both acetate arms were on the same side of the plane with respect to the central pyridyl moiety, while they were opposite in structure A, similar to the geometry of the [Lu(pypa)]− complex, which was previously identified as nine-coordinated by crystallography.23 Lu3+ is slightly larger than Sc3+ (ionic radii = 0.87 vs 0.98 Å, coordination number = 8),29 and the common coordination number for Sc3+ is between 6 and 8 vs 8 and 9 for Lu3+. However, upon comparing the bond lengths between the structure A and the [Lu(pypa)]− complex, the average M−N bonds were similar while the Sc−O bonds were shorter than the Lu−O bonds, suggesting that the [Sc(pypa)]− complex in this geometry was also nine-coordinated. In fact, this conformation was also energetically more favorable than structure B. With longer average bond distances between the donor atoms and the Sc3+ ion (Table 1), structure B was about 22.4 kJ/mol less stable than was structure A. Nonetheless, the small energy gap reasonably justifies the coexistence of two conformations, with structure A dominating. As seen in the VT-NMR spectra (Figure 2), the isomeric equilibrium shifted toward the major one as the temperature elevated but reversed to the initial position as soon as the temperature cooled down. On the basis of the DFT calculation, the transformation could possibly happen by switching the positions of O3 and N4 in structure B. One possible mechanism could involve breaking the Sc−O3 bond, followed by rearrangement of the Sc−N4 bond and finally reformation of the Sc−O3 bond on the opposite side. Due to the particularly long bond distance between N4 and the Sc3+ ion (2.8345 Å, 0.2684 Å longer than that in the structure A), it is also possible that both the Sc−O3 and Sc−N4 bonds were broken, rearranged, and then reformed. Either way, the transformation to structure A resulted in significantly stronger interactions between the metal center and the backbone nitrogen atoms (i.e., N2−N4), and thus a more stable complex.

Figure 3.

Two isomeric species of the [Sc(pypa)]− anion simulated using DFT calculations.

Table 1.

Comparison of DFT Calculated Sc−O and Sc−N Bond Lengths in Structures A and B

| structure A | structure B | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| atom 1 | atom 2 | length (Å) | atom 1 | atom 2 | length (Å) |

| Sc | N1 | 2.3500 | Sc | N1 | 2.4174 |

| Sc | N2 | 2.5647 | Sc | N2 | 2.6676 |

| Sc | N3 | 2.4960 | Sc | N3 | 2.5960 |

| Sc | N4 | 2.5661 | Sc | N4 | 2.8345 |

| Sc | N5 | 2.3495 | Sc | N5 | 2.4198 |

| Sc | O1 | 2.1925 | Sc | O1 | 2.1915 |

| Sc | O2 | 2.2149 | Sc | O2 | 2.2190 |

| Sc | O3 | 2.2115 | Sc | O3 | 2.1436 |

| Sc | O4 | 2.1872 | Sc | O4 | 2.2279 |

Solution Thermodynamics.

Due to the competition between the metal ion and protons for the binding sites of a chelator, the basicity of different ionizable and nonionizable protons is an essential consideration when evaluating the metal complexation. In our previous publication, we reported that H4pypa possessed a total of nine protonation sites, and all the protonation constants were determined using combined potentiometric-spectrophotometric titrations and UV in-batch spectrophotometric titrations.23 H4pypa was found to be a moderately basic chelator with the highest pKa being 7.78, assigned to one of the protonated tertiary amines in the pyridyl backbone,23 suggesting that at physiological pH (~7.4) the competition from protons is not a significant concern, as compared to more basic chelators, such as H4octox (Chart 1, highest pKa = 10.65).30 Furthermore, the complex formation equilibria of H4pypa with In3+, Lu3+, and La3+ were studied,19 and the complex stability (pM) followed the order of In3+ (30.5) > Lu3+ (22.6) > La3+ (19.9), opposite their ionic radii (In3+< Lu3+ < La3+).29 From this observation, we concluded that the binding cavity of H4pypa was best suited to fit the smaller In3+ ion.

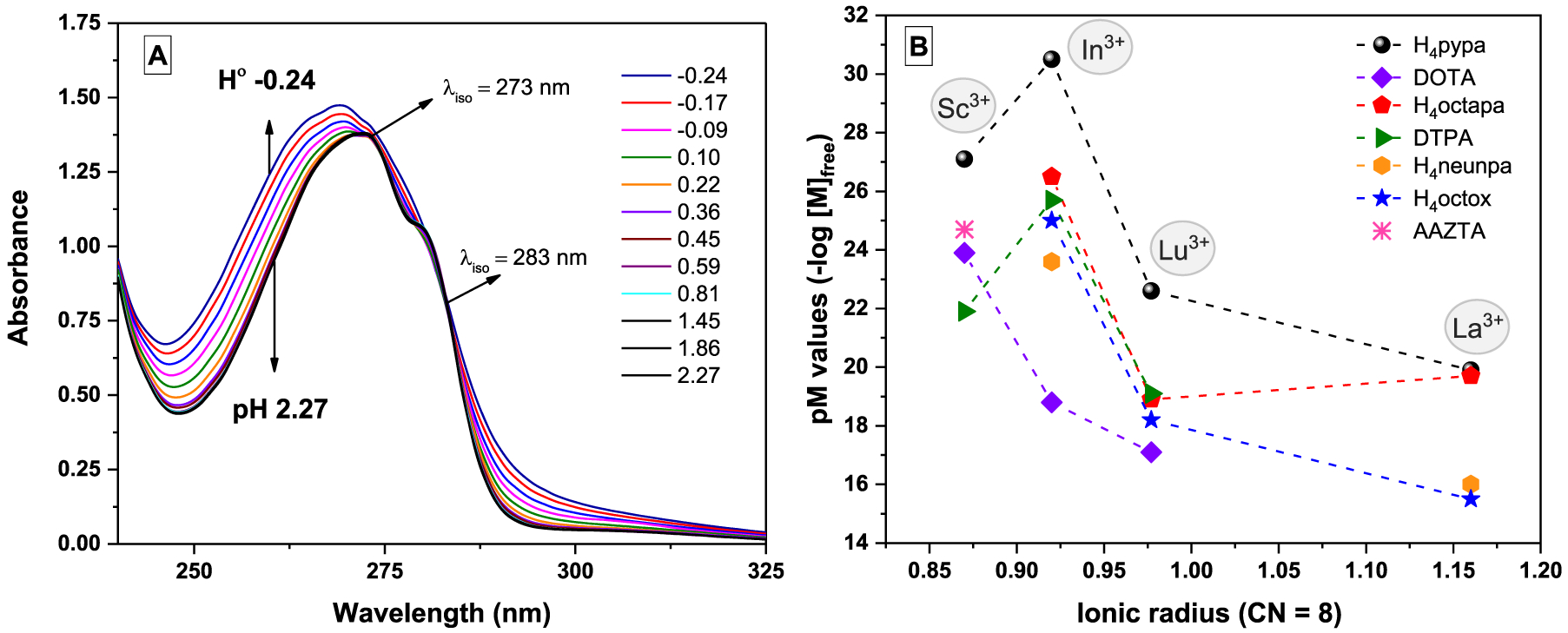

In this paper, Sc3+ is the subject metal ion of interest with an even smaller ionic radius compared to that of In3+ (0.87 Å vs 0.92 Å, 8-coordinated).29 To investigate the complexation equilibria of the Sc3+-H4pypa system, similar studies were conducted to determine the thermodynamic stability constant (log KSc(pypa)). Because the complexation between Sc3+ and H4pypa was complete at pH ≤ 2, direct determination of log KSc(pypa) by potentiometric titration was not feasible. Alternative approaches using a ligand−ligand competition method with an EDTA competitor (Chart 1), as well as acidic in-batch UV spectrophotometric titrations (Figure 4A), were required to first determine the stability constant of the protonated species ([Sc(Hpypa)]). Once log KSc(Hpypa) was known, direct potentiometric methods were used to determine the stability constants of the [Sc(pypa)]− and [Sc(OH)-(pypa)] species. Potentiometric and spectrophotometric experimental data were refined using the Hyperquad201331 and HypSpec201432 programs. The thermodynamic stability constant of [Sc(pypa)]− (log K[Sc(pypa)]−) was finally calculated to be around 26.98(1) (0.16 M NaCl, 25 °C; Table S1), which is similar to that of [Sc(AAZTA)]− (log KSc(AAZTA) = 27.69(4), 0.1 M KCl, 25 °C)22 and around 3.8 units lower than that of [Sc(DOTA)]− (log KSc(DOTA) = 30.79, 0.1 M Me4NCl, 25 °C).33 In order to accurately compare the stability with other complexes involving different chelators, a parameter that accounts for not only the stability constant but also the basicity and the denticity of the chelator is necessary. Therefore, the pSc value (−log [M]free at [L] = 10 μM, [M] = 1 μM and pH = 7.4) was adopted for a comprehensive measurement of the metal sequestering ability. The calculated pSc value of the Sc3+-H4pypa system was 27.1 (Table S1), which is more than two units higher than that of AAZTA (24.7) and more than three units higher than that of DOTA (23.9).18 The exceptionally high log KSc(pypa) and pSc values unequivocally manifest the superiority of H4pypa over both DOTA and AAZTA to form more thermodynamically stable complexes with the Sc3+ ion at physiological pH (7.4). Unexpectedly, as depicted in Figure 4B, [Sc(pypa)]− was an exception in the otherwise size-dependent pM value of the M3+-H4pypa systems (M3+ = Sc3+, In3+, Lu3+, and La3+). It could be interpreted that the size of the In3+ ion is the most suitable for the binding cavity of H4pypa among the four metal ions studied. Nonetheless, all of them, once again, exhibited superior metal ion scavenging ability over complexes with the comparison chelators.

Figure 4.

(A) Representative spectra of the in-batch UV-titration of the Sc3+-H4pypa system as the pH is raised. [L] = [Sc3+] = 1.33 × 10−4 M at 25 °C, l = 1 cm. The ionic strength was maintained constant (I = 0.16 M) when possible by the addition of different amounts of NaCl. (B) pM vs ionic radius29 for M3+ ions of interest and ligands discussed.

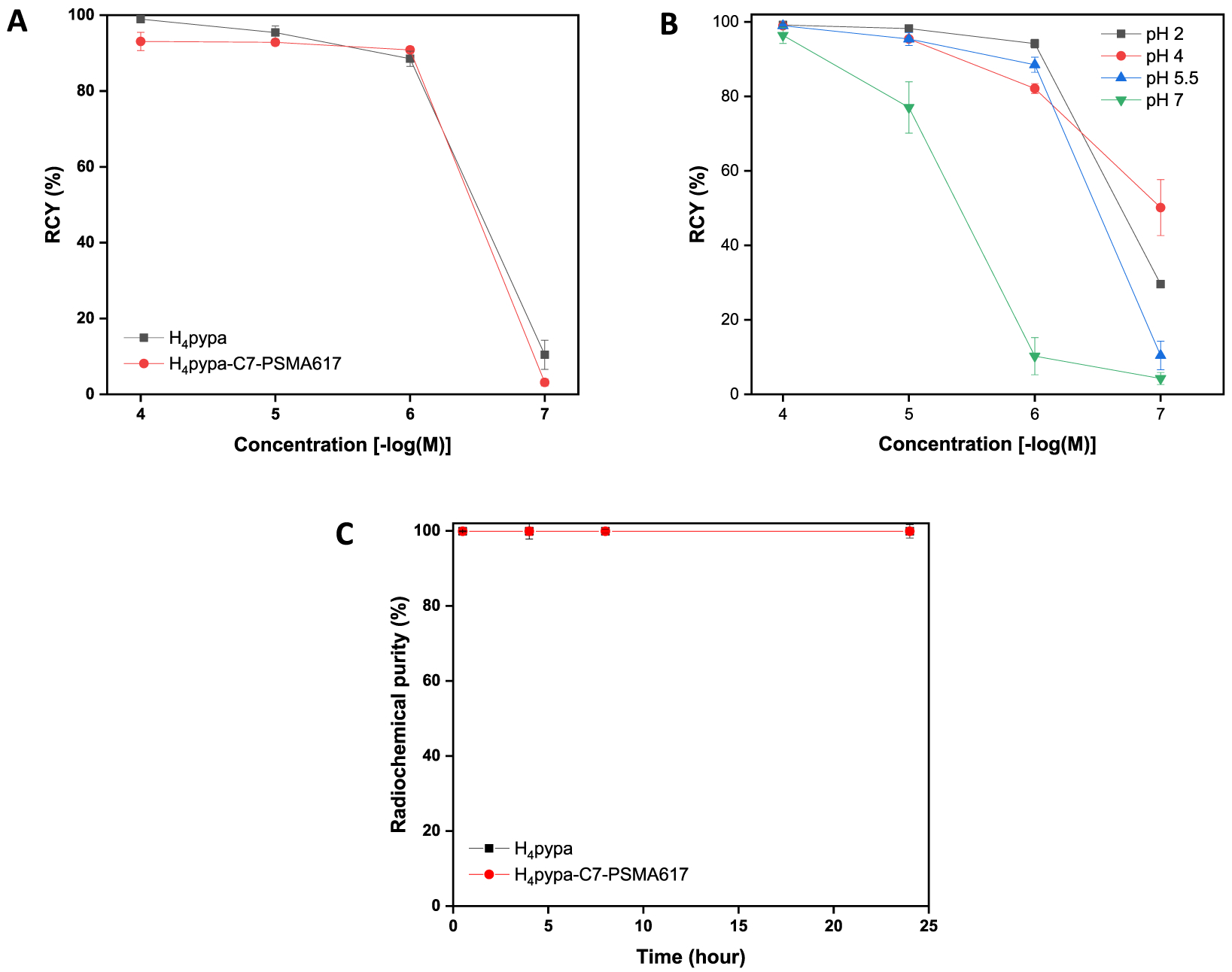

Radiolabeling and Mouse Serum Challenge Experiment.

All the radiolabeling experiments with H4pypa and H4pypa-C7-PSMA617 presented here were performed at room temperature, and the samples were agitated during incubation. The radiochemical yield was determined with instant thin layer chromatography plates impregnated with silicic acid (iTLCSA), developed in sodium citrate (0.4 M, pH = 4.5), and the radiocomplexes were confirmed with radioactive high-performance liquid chromatography (radio-HPLC; Figure S15). Initial concentration-dependent radiolabeling at room temperature demonstrated that both H4pypa and H4pypa-C7-PSMA617 radiolabeled scandium-44 (2.9 MBq) efficiently in 5 min (0.5 M NH4OAc buffer, pH = 5.5; Figure 5A), with apparent molar activities (end-of-bombardment (EoB)-corrected) of 45 GBq/ μmol and 44 GBq/μmol, respectively. The calculated apparent molar activity increased when the radiolabeling mixtures were incubated longer (48 GBq/μmol (30 min) and 53 GBq/μmol (60 min) for H4pypa; 47 GBq/μmol (30 min) and 52 GBq/μmol (60 min) for H4pypa-C7-PSMA617; Tables S2 and S4). In order to investigate the effects of pH on the radiolabeling efficiency, pH-dependent radiolabeling experiments with the same amount of radioactivity (i.e., 2.9 MBq) were carried out, showing that the radiolabeling of H4pypa with scandium-44 was the most efficient at pH = 2 (98 ± 0% at 10−5 M, 94 ± 1% at 10−6 M, 15 min) and gradually deteriorated as the pH increased (77 ± 7% at 10−5 M, 10 ± 5% at 10−6 M, pH = 7, 15 min; Figure 5B and Table S3). This phenomenon could be explained by metal ion hydrolysis, supported by studies which proved that different scandium(III) hydrolysis products or the dimeric hydrolysis complex ([Sc2(μ-OH)2(H2O)10]4+) could form at pH ≥ 1, contingent on the concentration and ionic strength.34,35 Nonetheless, in our radiolabeling study, decent yields were still attained at pH = 4 and 5.5 (95 ± 2% and 96 ± 2% at 10−5 M; 82 ± 1% and 89 ± 2% at 10−6 M, respectively, in 15 min).

Figure 5.

(A) Concentration-dependent radiolabeling studies of H4pypa and H4pypa-C7-PSMA617 with 44Sc at room temperature in NH4OAc buffer (0.5 M, pH = 5.5) over 5 min. (B) Concentration-dependent radiolabeling studies of H4pypa with 44Sc at room temperature in NH4OAc solution (0.5 M, pH = 2, 4, 5.5, 7) over 15 min. (C) Mouse serum stability of the corresponding complexes over 24 h at 37 °C.

These radiolabeling results are in sharp contrast with that of the “gold standard” DOTA, reported in the recent, [44Sc][Sc-(AAZTA)] study (~0% RCY in 15 min, 0.2 M NH4OAc buffer pH = 4, 0.1 MBq 44Sc, [DOTA] = 0.1 μM).22 Under the same conditions as DOTA, ~60% RCY was obtained for AAZTA,22 which is similar to [44Sc][Sc(pypa)]− (50 ± 8% RCY, RT, 15 min, pH = 4, 0.1 μM; Table S3); however, more 44Sc was used in labeling H4pypa (~2.9 MBq). Also, similar pH-dependent radiolabeling was observed with AAZTA, which possessed the highest affinity for scandium-44 in the pH range 3−4, and declined as the pH was raised (0.3 μM, 0.1 MBq, 95 °C, 5 min); DOTA, however, yielded only ~15% RCY under the same labeling conditions even at its optimal pH of 3.22 Another study with DOTATOC reported by Pruszyński et al. demonstrated that a temperature as high as 115 °C was necessary for >90% radiolabeling (15 min, pH = 4).36

After the successful radiolabeling studies, both [44Sc][Sc(L)] (L = pypa and pypa-C7-PSMA617) were challenged with mouse serum. The complexes remained intact in the presence of the mouse serum proteins for at least six half-lives of scandium-44 with <1% transchelation (Figure 5C), which is extremely encouraging, considering the efficient radiolabeling at room temperature that H4pypa offers.

PET/CT Imaging, Biodistribution Studies, and Binding Affinity.

The binding affinities of H4pypa-C7-PSMA617 to PC3-PIP (PSMA+) and PC3-Flu (PSMA−) cell lines were compared using a series of diluted H4pypa-C7-PSMA617 solutions in the presence of a small amount of [44Sc][Sc(pypa-C7-PSMA617)]. The study was performed under the assumptions that the radiolabeling would not affect the binding of the PSMA ligands to the cell surface receptors, and due to the small portions of the radiolabeled tracers, its influence on overall binding was omitted. The results revealed the PSMA-specific binding of H4pypa-C7-PSMA617 with high affinity (KD = 2.96 ± 0.81 nM and Bmax = 7.84 ± 0.37 fmol/ mg; Figure S18).

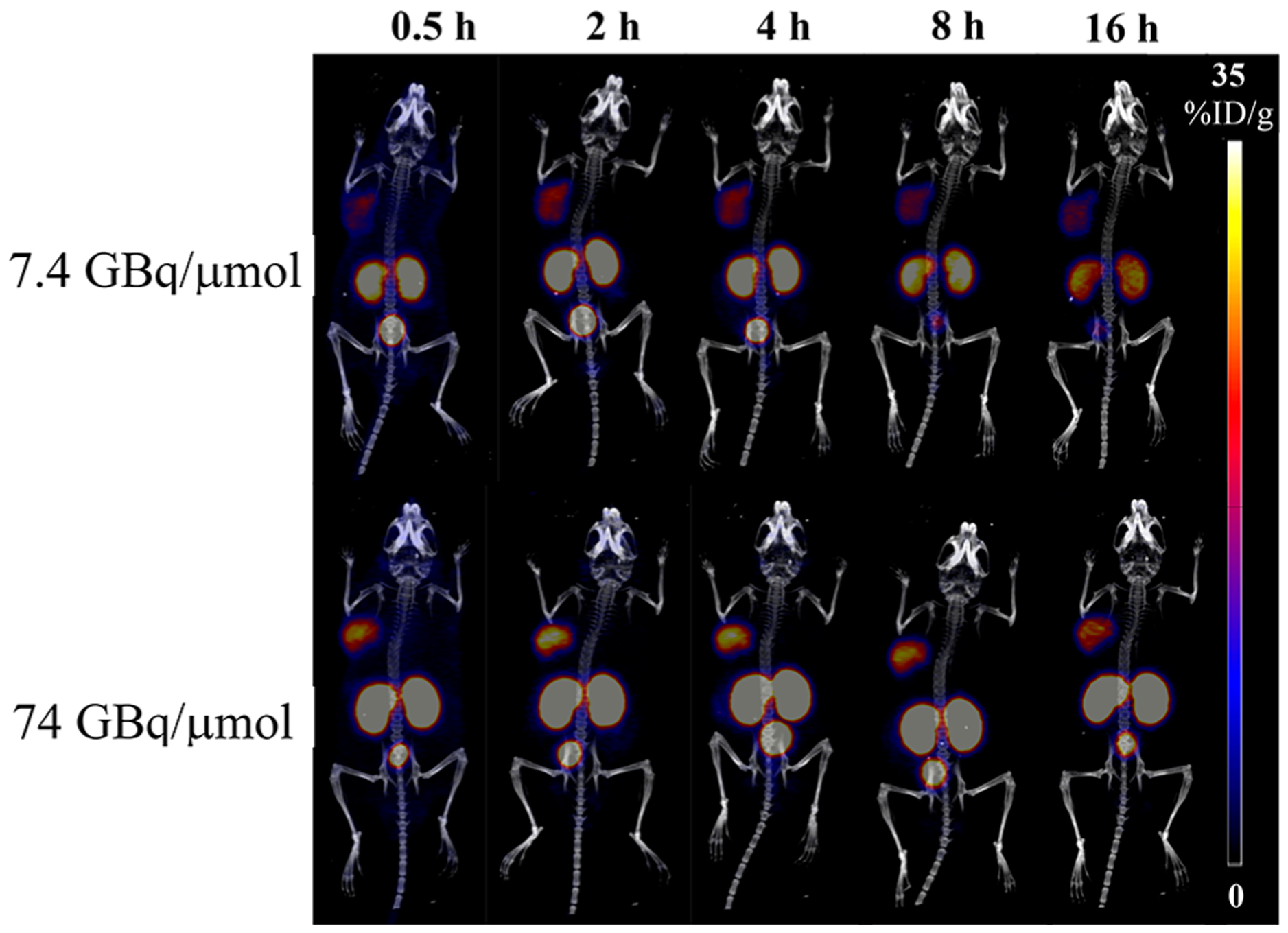

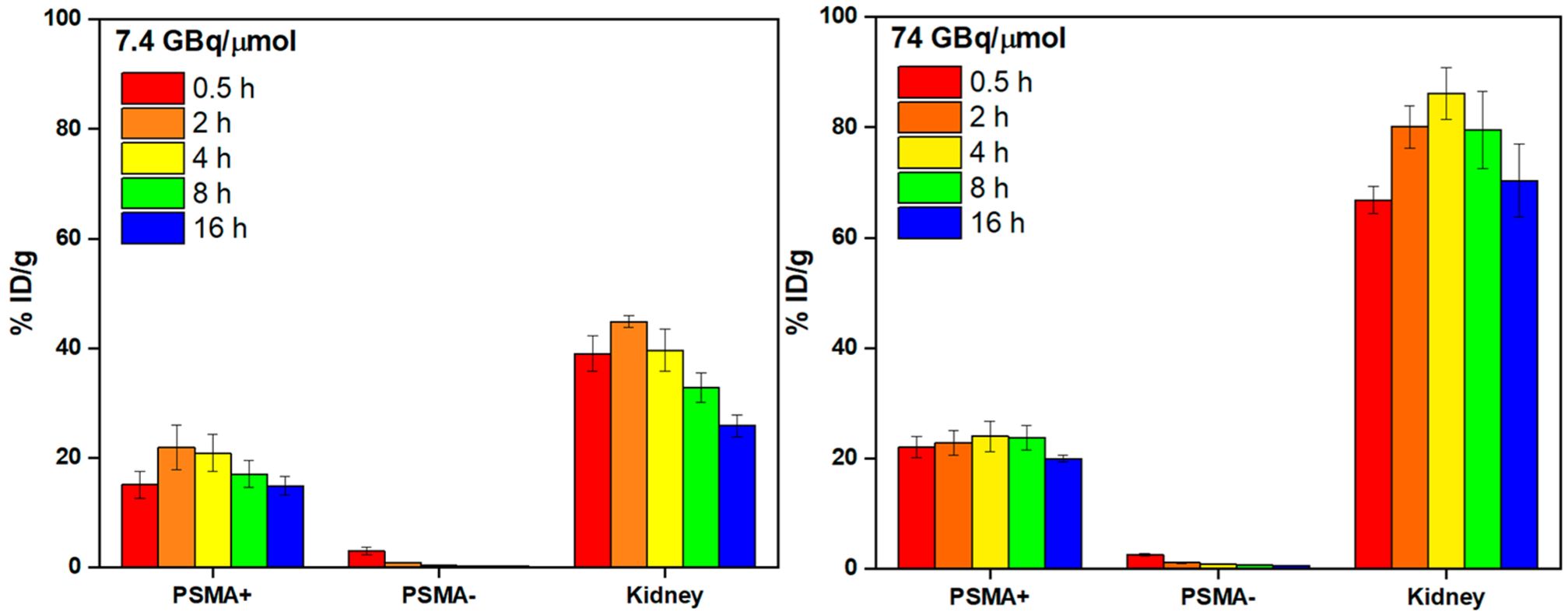

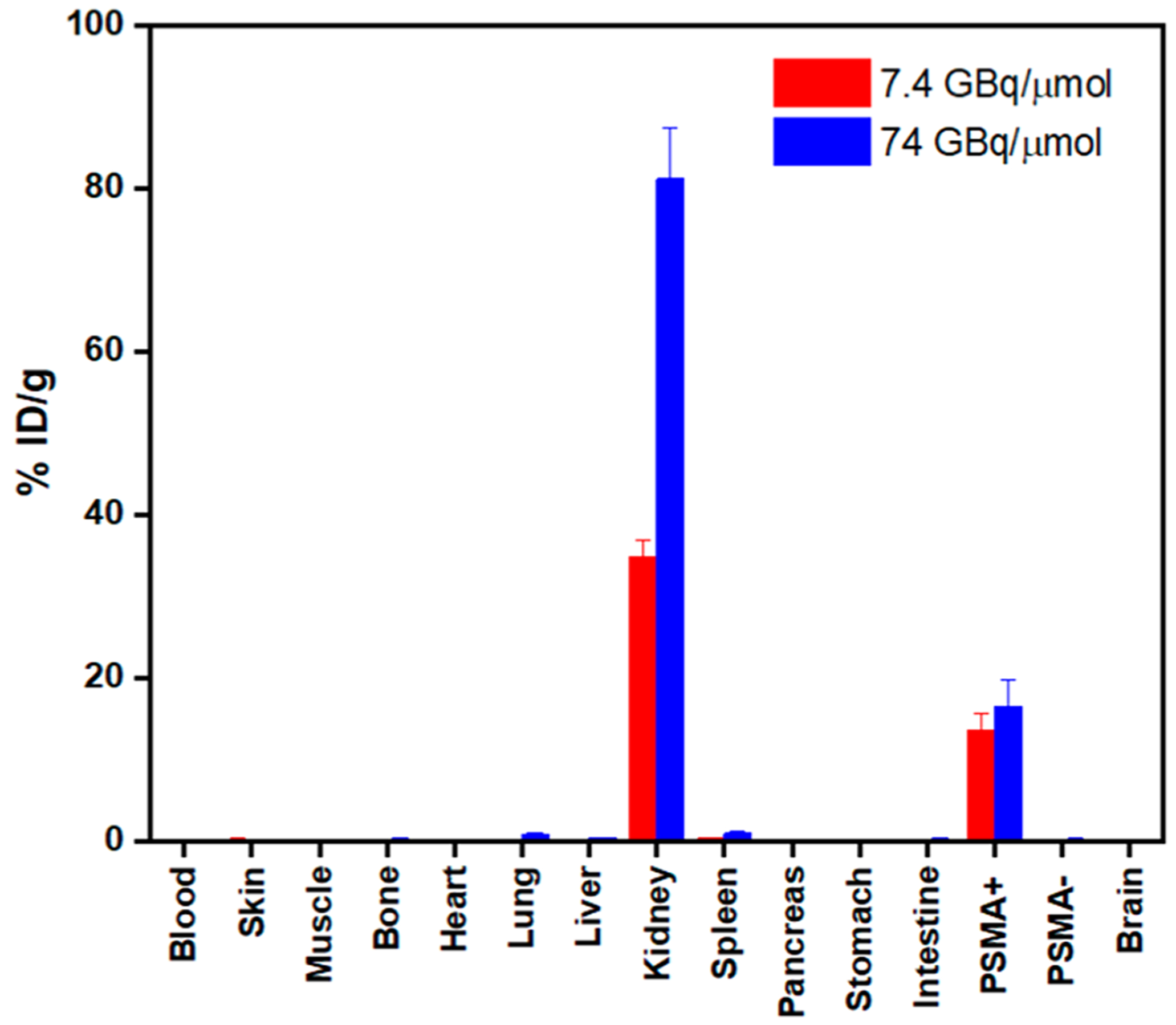

For in vivo study, two batches of radiotracers were prepared with two different apparent molar activities (7.4 GBq/μmol and 74 GBq/μmol) and then injected into nude mice (n = 3) bearing both PSMA-positive (PC3-PIP, left shoulder) and PSMA-negative (PC3-Flu, right shoulder) tumors to investigate the targeting specificity of the tracer, as well as the effects on pharmacokinetics associated with the injected molar activity. Both PET/CT images (Figure 6) and ex vivo biodistribution study (Figures 7, 8) showed that the 44Sc-labeled H4pypa-C7-PSMA617 was excreted renally and collected through the bladder, while the tumor accumulation was PSMA-specific. In both experiments, the biodistributions of the radiotracers were largely similar, and the tumor uptake was rapid. After 30 min, the tumor radioactivity had already reached 15.1 ± 2.4% ID/g (% injected dose/g; 7.4 GBq/μmol) and 22.1 ± 1.9% ID/g (74 GBq/μmol). In both cases, the accumulation peaked at 4 h postinjection (p.i.; 20.9 ± 3.4% and 24.0 ± 2.8% ID/g, respectively) and gradually reduced over time. Nonetheless, the tumor retention was effective at 14.9 ± 1.7% ID/g (7.4 GBq/μmol) and 20.0 ± 0.6% ID/g (74 GBq/μmol) after about four half-lives of scandium-44. Unexpectedly, comparing the two profiles, although lower apparent molar activity contributed to slightly reduced tumor uptake, it significantly brought down the kidney accumulation by more than half (Figure 8). Consequently, with 7.4 GBq/μmol, the tumor-to-kidney ratio increased considerably from 0.39 (30 min p.i.) to 0.57 (16 h p.i.), as opposed to around 0.28 throughout the study when using 74 GBq/μmol (Figure S19). Besides the kidney, the background radioactivity generally decreased in tandem with the injected molar activity, leading to much higher tumor-to-background ratios. The contrasts were particularly prominent in blood (113 vs 63), bone (91 vs 61), heart (194 vs 83), lung (85 vs 18), liver (113 vs 37), spleen (34 vs 17), and pancreas (194 vs 83) (16 h p.i.; Table S5). This phenomenon, however, should not be generalized to all PSMA-targeting radiotracers. The results reported by Fendler et al. showed that [177Lu][Lu(DOTAPSMA617)] with high molar activity was related to a higher tumor-to-background ratio.37 Therefore, it is crucial to evaluate the effect associated with the molar activity independently for each radiotracer to attain an optimal tumor-to-background contrast.

Figure 6.

Representative PET/CT images (MIP, coronal) of [44Sc][Sc(pypa-C7-PSMA617)] (7.4 (top) and 74 (bottom) GBq/μmol)] in PC3-PIP (left shoulder) and PC3-Flu (right shoulder) tumor-bearing mice at different p.i. time points.

Figure 7.

Biodistribution data of [44Sc][Sc(pypa-C7-PSMA617)] (7.4 (left) and 74 (right) GBq/μmol)] in PC3-PIP-tumor-bearing mice at selected p.i. time points (n = 3 per time point).

Figure 8.

Ex vivo biodistribution data of [44Sc][Sc(pypa-C7-PSMA617)] (7.4 and 74 GBq/μmol)] in PC3-PIP-tumor-bearing mice at selected p.i. time points (n = 3 per time point).

Despite different tumor models being used, the pharmacokinetics of [44Sc][Sc(pypa-C7-PSMA617)] resembled those for the published 111In-analog, especially the strong kidney retention, but were drastically different from the 177Lu-counterpart where the clearance from the background organs/tissues was much faster, including the kidney (~2% ID/g at 24 h p.i.), leaving the tumor with major radioactivity accumulations (~14% ID/g at 24 h p.i.).23 The observed differences in the biological behavior of 44Sc- and 177Lu-labeled H4pypa-C7-PSMA617 were unexpected since it was contrary to that of 44Sc- and 177Lu-labeled DOTA-PSMA617, which appeared to have similar biodistributions.13 In the same tumor models (PC-3 PIP/Flu), both 44Sc- and 177Lu-labeled DOTAPSMA617 were rapidly cleared from the background tissues/ organs, including the kidney (~2−3% ID/g at 6 h p.i.), while their tumor (PSMA+) uptakes and the tumor-to-kidney ratios were comparable (~52–55% ID/g and 17–23, respectively, at 6 h p.i.).13 The similarity renders [44Sc][Sc(DOTAPSMA617)] a promising pretherapeutic imaging agent for the 177Lu counterpart, while the discrepancies in [44Sc][Sc-(pypa-C7-PSMA617)] and [177Lu][Lu(pypa-C7-PSMA617)] suggested that the biochemical properties of 44Sc- and 177Lu-labeled pypa complexes are different. Nonetheless, the biodistribution of a radiotracer is heavily dependent on the targeting molecule, and therefore, the differences observed in [44Sc][Sc(pypa-C7-PSMA617)] and [177Lu][Lu(pypa-C7-PSMA617)] cannot be generalized to other bioconjugates with different targeting vectors. What is important from this animal study is the demonstration of the exceptional in vivo stability of the [Sc(pypa)]− complex, which can be radiolabeled with a simple and robust procedure in 5 min at room temperature, compatible with the temperature-sensitive bio-molecules such as the antibody and antibody fragment. These advantages would be particularly valuable for imaging at late time points and could be exploited when using scandium-47 (t1/2 = 3.35 days) or lutetium-177 as the therapeutic agents for targeted radioligand/radioimmunotherapy.

CONCLUSION

The potentially nonadentate nonmacrocyclic chelator, H4pypa, which previously demonstrated excellent affinities for both In3+ and Lu3+ ions,23 has also presented highly stable chelation with the Sc3+ ion. The complex was synthesized and characterized by HR-ESI-MS and a range of NMR spectroscopic techniques. On the basis of the 1H NMR spectrum, [Sc(pypa)]− in aqueous solution (pH = 7) existed as two isomers (major and minor) in an equilibrium further shifted toward the major conformation as the temperature was raised (>25°C). The structures of both isomers were predicted by DFT calculation with a small energy difference of 22.4 kJ/mol, rendering their coexistence reasonable. In addition, the formation constant (log KSc(pypa)) and pSc value of the [Sc(pypa)]− complex were calculated to be 26.98(1) and 27.1 (Table S1), respectively, significantly higher than those of [Sc(DOTA)]− and [Sc(AAZTA)]−. Furthermore, radiolabeling experiments with scandium-44 confirmed efficient radio-metalation at room temperature in 5–15 min at a chelator concentration as low as 10−6 M (pH = 2–5.5), resulting in a highly stable complex upon mouse serum challenge over at least six decay half-lives. Lower pH also led to better radiolabeling (i.e., higher radiochemical yield at lower concentration), possibly due to the facile Sc(III) hydrolysis. To further evaluate the biological applicability of [Sc(pypa)]−, PSMA-targeting [44Sc][Sc(pypa-C7-PSMA617)] was injected into tumor-bearing nude mice in two molar activities, demonstrating PSMA-dependent accumulation and excellent long-term stability. To our surprise, considerable influences from the apparent molar activity on the pharmacokinetic profile were observed where lower apparent molar activity (7.4 GBq/μmol) substantially increased the tumor-to-background ratio. This finding is important for radiotracer formulation to optimize the biodistribution profile. Most importantly, the long-term in vivo stability presented H4pypa as a promising chelator for scandium-44, and even scandium-47, as a theranostic radiopharmaceutical which can be exploited for immuno-PET imaging and targeted radio-therapy as well.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

Materials and Methods.

All solvents and reagents were purchased from commercial suppliers (TCI America, Alfa Aesar, AK Scientific, Sigma-Aldrich, Fisher Scientific, Fluka) and were used as received. 1H, 13C, 1H−13C HSQC, 1H−13C HMBC, COSY, and NOESY NMR spectra were recorded at ambient and elevated temperature on Bruker AV400 instruments, as specified; the NMR spectra are expressed on the δ scale and were referenced to residual solvent peaks. Low-resolution (LR) mass spectrometry was performed using a Waters ZG spectrometer with an ESCI electrospray/chemical-ionization source, and high-resolution electrospray-ionization mass spectrometry (HR-ESI-MS) was performed on a Micromass LCT time-of-flight instrument at the Department of Chemistry, University of British Columbia. Analyses of radiolabeled compounds were performed with both iTLC-silicic acid impregnated plates (iTLC-SA) purchased from Agilent Technologies and radio-HPLC. The TLC scanner model was a BIOSCAN (system 200 imaging scanner), and the HPLC system was from Agilent Technologies (1200 series). A DIONEX Acclaim C18 5 μm 120 Å column (250 mm × 4.60 mm) was used for separation of free radioactivity and the radio-complex. 44Sc was provided by the UW—Madison Cyclotron Lab in 0.1 M HCl solution (~259 MBq). Deionized water was filtered through the PURELAB Ultra Mk2 system.

Na[natSc(pypa)].

H4pypa·2TFA·2H2O (10.5 mg, 1.27 × 10−5 mol, 1 equiv) was dissolved in H2O (0.5 mL) in a scintillation vial, and 0.1 M NaOH (aq) was added to adjust the pH to 7. ScCl3·6H2O (4.93 mg, 1.91 × 10−5 mol, 1.5 equiv) was added. The mixture was stirred at room temperature for 1 h, and the complexation was confirmed by LR-ESI-MS. The reaction mixture was dried in vacuo and then redissolved in D2O for NMR spectroscopic characterizations. 1H NMR (400 MHz, 343 K, D2O): δ 8.73−8.66 (m, 2H), 8.49 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 8.42 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 8.38 (d, J = 7.7 Hz, 1H), 8.36−8.31 (m, 2H), 7.98 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.82 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 5.66 (d, J = 15.1 Hz, 1H), 5.47 (d, J = 15.3 Hz, 1H), 5.39 (d, J = 14.9 Hz, 1H), 5.32 (d, J = 15.4 Hz, 1H), 5.21 (d, J = 15.3 Hz, 1H), 5.16−5.11 (m, 2H), 4.64 (d, J = 17.5 Hz, 1H), 4.46 (d, J = 16.7 Hz, 1H), 4.34 (d, J = 16.9 Hz, 1H), 4.03 (d, J = 17.6 Hz, 1H), 3.82 (d, J = 17.6 Hz, 1H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, 343 K, D2O): δ 179.0, 178.2, 176.8, 173.0, 159.2, 158.6, 158.2, 157.8, 150.0, 149.5, 142.9, 142.6, 142.3, 127.1, 126.8, 123.5, 123.0, 122.4, 63.1, 62.9, 62.2, 61.4, 60.1 HR-ESI-MS calcd for [C25H21N5O845Sc + 2H]+: 566.1106. Found [M + 2H]+: 566.1102.

DFT Calculations.

All DFT simulations were performed as implemented in the Gaussian 09 revision D.01 suite of ab initio quantum chemistry programs (Gaussian Inc., Wallingford, CT). The B3LYP functional38,39 and the effective core potential LanL2DZ basis sets for Sc40−42 were applied to optimize the structural geometry in the presence of water solvent (IEF PCM as implemented in G09) without the use of symmetry constraints. Normal self-consistent field (SCF) and geometry convergence criteria were conducted for all the calculations. The calculated structures were visualized using Mercury 4.1.

Solution Thermodynamics.

All potentiometric titrations were carried out with a Metrohm Titrando 809 and a Metrohm Dosino 800 with a Ross combined electrode. A 20 mL and 25 °C thermostated glass cell with an inlet−outlet tube for nitrogen gas (purified through a 10% NaOH solution to exclude any CO2 prior to and during the course of the titration) was used as a titration cell. The electrode was daily calibrated in hydrogen ion concentration by direct titration of HCl with freshly prepared NaOH solution, and the results were analyzed with the Gran procedure43 in order to obtain the standard potential E° and the ionic product of water pKw at 25 °C and 0.16 M NaCl used as a supporting electrolyte. Solutions were titrated with carbonate-free NaOH (0.16 M) that was standardized against freshly recrystallized potassium hydrogen phthalate. In the study of complex formation equilibria, the determination of the stability constants of the Sc(Hpypa) species was carried out by two different methods. The first method used UV−vis spectrophotometric measurements on a set of solutions containing a 1:1 metal to ligand molar ratio ([H4pypa] = [M]3+ = 1.33 × 10−4 M) and different amounts of standardized HCl and NaCl to set the ionic strength constant at 0.16 M when possible. The equilibrium H+ concentration in this UV in batch titration procedure at low pH solutions (2 ≥ pH ≤ 0) was calculated from solution stoichiometry, not measured with a glass electrode. For the solutions of high acidity, the correct acidity scale H0 was used.44 The spectral range was 200−400 nm at 25°C and a 1 cm path length. The molar absorptivities of all the protonated species of H4pypa calculated with HypSpec201432 from the protonation constant experiments23 were included in the calculations. The second method used competition pH-potentiometric titrations with EDTA as a ligand competitor, and the composition of the solutions was [M]3+ = Sc3+ ~ 1.54 × 10 −3 M, [H4pypa] ~ 7.07 × 10 −4 M, and [EDTA] ~ 1.55 × 10 −3 M at 25 °C and I = 0.16 M NaCl. The stability constants for the complexes formed by EDTA and Sc3+ were from the literature.45 Direct pH-potentiometric titrations of the Sc3+-H4pypa systems were also carried out. Sc3+ metal ion solution was prepared by adding the atomic absorption (AA) standard solution to a H4pypa solution of known concentration in the 1:1 metal to ligand molar ratio. Ligand and metal concentrations were in the range of (8.40−8.53) × 10−4 M. The exact amount of acid present in the AA standard solution was determined by Gran’s method43 of titrating equimolar solutions of Sc(III) and Na2H2-EDTA. Each titration consisted of 100−150 equilibrium points in the pH range 1.6−11.5; equilibration time for titrations was up to 5 min for metal complex titrations. Three replicates of each titration were performed. Relying on the stability constants for the species Sc(Hpypa) obtained by the two different methods, the fitting of the direct potentiometric titrations was possible and yielded the stability constants in Table S1. All the potentiometric measurements were processed using the Hyperquad2013 software,31 while the obtained spectrophotometric data were processed with the HypSpec201432 program. Proton dissociation constants corresponding to hydrolysis of Sc(III) aqueous ions included in the calculations were taken from Baes and Mesmer.34 The overall equilibrium (formation) constants log β referred to the overall equilibria pM + qH + rL ⇆ MpHqLr (the charges are omitted), where p might also be 0 in the case of protonation equilibria and q can be negative for hydroxide species. Stepwise equilibrium constants log K correspond to the difference in log units between the overall constants of sequentially protonated (or hydroxide) species. The parameter used to calculate the metal scavenging ability of a ligand toward a metal ion, pM, is defined as −log [Mn+]free at [ligand] = 10 mM and [Mn+] = 1 μM at pH = 7.4.46

Production and Radiochemical Isolation of Scandium-44.

Scandium-44 was cyclotron-produced using natCa[p,n]4xSc nuclear reactions on pressed targets of metallic calcium (300−350 mg). Target preparation was performed in the air and rapidly mounted in the cyclotron to reduce calcium oxidation. Irradiations were performed at 20 μA for 1 h with direct water cooling, and a 12.7 μm Nb foil was used to degrade the beam energy from the nominal 16 MeV to 14.1 MeV. Under these conditions, a scandium-44 production yield of 0.4 mCi/μAh was obtained through the reaction of natCa(p,n)44Sc. Isolation of the produced scandium-44 was carried out by single column extraction chromatography using an N,N,N′,N′-tetrakis-2-ethylhexyldiglycolamide functionalized resin (DGA-branched, Eichrom).40 The target was dissolved in 9 M HCl (10 mL) and passed through a 1 mL fritted solid phase extraction (SPE) tube filled with the DGA resin (~120 mg), loading the scandium-44 and eluting bulk Ca2+. Remaining Ca2+ was removed by rinsing the column with 4 M HCl (20 mL). Next, a 12 mL wash with 1 M HNO3 was performed to elute possible trace metal contaminants such as Zn, Fe, and Cu. Finally, scandium-44 was eluted in a small volume using 0.1 M HCl (4 × 500 μL fractions). The radionuclidic and chemical purity were confirmed by high purity germanium (HPGe) gamma spectrometry and microwave plasma atomic emission spectroscopy (MP-AES), respectively.

Radiolabeling Studies.

An aliquot of ligand solution (H4pypa or H4pypa-C7-PSMA617) (10 μL) in NH4OAc solution (88 μL, 0.5 M, pH = 2, 4, 5.5, 7) was mixed with around 2.9 MBq of scandium-44 (2 μL). The reactions were agitated at ambient temperature over the desired period. The mixture (3 μL) was spotted on an iTLC-SA plate and then developed in sodium citrate buffer (0.4 M, pH = 4.5). The TLC plate was read by a TLC reader, showing the free metal ion migrated to the solvent front while the complex stayed at the baseline. The areas of both peaks were used to calculate RCY %. The complex was also confirmed with radio-HPLC (A, H2O/0.1% TFA; B, ACN/0.1%TFA, 5% - 65% B over 32 min, 1 mL/min): [44Sc][Sc(pypa)] (tR = 13.41 min); [44Sc][Sc(pypa-C7-PSMA617)] (tR = 23.67 min); free 44Sc (tR = 3.50 min).

In Vitro Mouse Serum Challenge.

To the radiolabeled sample, an equal volume (100 μL) of mouse serum was added. The mixture was incubated at 37 °C, and 5 μL aliquots were collected at desired time points (0.5 h, 4 h, 8 h, 24 h). The aliquot was spotted onto the iTLC-SA plate next to the control spot (free scandium-44 in serum without chelator) and developed in sodium citrate solution (0.4 M, pH = 4.5). The TLC plate was read by a TLC reader. The free metal ion migrated to the solvent front while the complex stayed at the baseline. The areas of both peaks were used to calculate RCY %.

In Vitro Competition Binding Assays.

To determine the binding affinity of H4pypa-C7-PSMA617 (in the presence of small amount of [44Sc][Sc(pypa-C7-PSMA617)]) for prostate cancer cells, a receptor saturation assay was performed as previously described.47 Briefly, 1 × 105 cells (either PC3-PIP or PC3-FLU) were plated into filter-bottom 96-well plates (Corning), and various concentrations of PSMA ligand solutions (0.03−100 nM) were incubated with the cells for 2 h. The amount of H4pypa-C7-PSMA617 ligands in nanomoles and corresponding radioactivity in μCi can be calculated by using the labeling efficiency (μCi/nmol) to allow accurate measurement of binding affinity. After the incubation period, the wells were rinsed and dried, and the filter papers were counted in an automated gamma counter to determine the amount of bound tracer. GraphPad Prism was utilized to plot saturation binding isotherms, and the affinity constant (KD) and maximum specific binding (Bmax) were determined.

Radiolabeling of Conjugates for in Vivo Study.

For the in vivo study, radiolabeling with scandium-44 was performed by mixing 111− 185 MBq (3−5 mCi) of radiometal ions with 15−25 nmol of H4pypa-C7-PSMA617 (7.4 or 74 GBq/μmol) in 0.5 M NaOAc buffer solution (pH = 5.5). The reactions were incubated for 30 min at room temperature under agitation (300 rpm). Next, the radio-conjugate was purified by reverse phase chromatography using Sep Pak C18 cartridges (Waters), eluted in absolute ethanol, dried at 70 °C in a N2 stream, and reconstituted in PBS. Quantitative radiochemical yields (>95%) and high radiochemical purities (>95%) were confirmed by radio-TLC using EDTA solution (50 mM, pH = 5.5) as a mobile phase and radio-HPLC.

PET/CT Imaging Studies.

All animal experiments were performed under the approval of the University of Wisconsin Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Male nude mice (6−8 weeks) were xenografted with (1.5−2.0) × 106 PC3-PIP (PSMA+) cells (left shoulder) and (1.5−2.0) × 106 PC3-FLU (PSMA-) cells (right shoulder) suspended in Matrigel (1:1). Tumor bearing mice were employed for in vivo imaging, when tumors reached a volume of 400−500 mm3. For noninvasive in vivo PET/CT imaging, mice (n = 3) were administered 5.5−11.1 MBq (150−300 μCi) of [44Sc][Sc(pypa-C7-PSMA617)] via tail vein injection. Following isoflurane anesthesia, mice were placed into a microPET/microCT scanner (Inveon, Siemens), and 40 million coincidence event static PET scans were acquired at different time points (0.5, 2, 4, 8, and 16 h postinjection, p.i.). CT scans were taken prior to each PET acquisition for attenuation correction and anatomical reference. Quantitative analyses of images were performed by manually drawing volumes of interest over the tumor and other organs of interest, and data were reported as percent injected dose per gram of tissue (%ID/ g), mean ± SD.

Ex Vivo Biodistribution Studies.

Ex vivo tissue distribution studies were performed to validate the in vivo imaging quantification results. After the last PET/CT scan, mice were sacrificed, and select organs were harvested, weighed, and counted in an automatic gamma counter (Wizard 2, PerkinElmer). Uptake in each tissue is reported as % ID/g (mean ± SD).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. Maria Ezhova for her useful advice on NMR experiments at UBC. We gratefully acknowledge funding from NSERC CREATE IsoSiM at TRIUMF for a Ph.D. research stipend (L.L.), both NSERC and CIHR for financial support via a Collaborative Health Research Project (CHRP to F.B., C.O., and P.S.), NSERC Discovery (C.O.), and financial support from the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number T32CA009206 (E.A.-S.). TRIUMF receives federal funding via a contribution agreement with the National Research Council of Canada.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.inorgchem.9b03347.

Representative spectra of the in-batch UV-titration of the Sc3+-pypa system as the pH is raised; stepwise protonation constants (log KHqL) of [Sc(pypa)]− ; NMR spectra (1H, 13C, HSQC, HMBC, COSY, NOESY) and high resolution mass spectra of [Sc(pypa)]− complex; radiochemical-yield data and radio-HPLC spectra of [44Sc][Sc(pypa)]− and [44Sc][Sc(pypa-C7-PSMA617)]− complexes; biodistribution studies data (%ID/g) and binding affinity graphs of [44Sc][Sc(pypa-C7-PSMA617)]− complex (PDF)

Complete contact information is available at: https://pubs.acs.org/10.1021/acs.inorgchem.9b03347

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Contributor Information

Lily Li, Medicinal Inorganic Chemistry Group, Department of Chemistry, University of British Columbia, Vancouver V6T 1Z1, Canada; Life Sciences Division, TRIUMF, Vancouver V6T 2A3, Canada;.

María de Guadalupe Jaraquemada-Peláez, Medicinal Inorganic Chemistry Group, Department of Chemistry, University of British Columbia, Vancouver V6T 1Z1, Canada;.

Eduardo Aluicio-Sarduy, Department of Medical Physics, University of Wisconsin—Madison, Madison, Wisconsin 53705, United States.

Xiaozhu Wang, Medicinal Inorganic Chemistry Group, Department of Chemistry, University of British Columbia, Vancouver V6T 1Z1, Canada;.

Dawei Jiang, Department of Medical Physics, University of Wisconsin—Madison, Madison, Wisconsin 53705, United States;.

Meelad Sakheie, Life Sciences Division, TRIUMF, Vancouver V6T 2A3, Canada.

Hsiou-Ting Kuo, Department of Molecular Oncology, BC Cancer, Vancouver V5Z 1L3, Canada.

Valery Radchenko, Department of Chemistry, University of British Columbia, Vancouver V6T 1Z1, Canada; Life Sciences Division, TRIUMF, Vancouver V6T 2A3, Canada.

Paul Schaffer, Life Sciences Division, TRIUMF, Vancouver V6T 2A3, Canada.

Kuo-Shyan Lin, Department of Molecular Oncology, BC Cancer, Vancouver V5Z 1L3, Canada;.

Jonathan W. Engle, Department of Medical Physics, University of Wisconsin—Madison, Madison, Wisconsin 53705, United States

François Bénard, Department of Molecular Oncology, BC Cancer, Vancouver V5Z 1L3, Canada;.

Chris Orvig, Medicinal Inorganic Chemistry Group, Department of Chemistry, University of British Columbia, Vancouver V6T 1Z1, Canada;.

REFERENCES

- (1).Zeglis BM; Lewis JS A Practical Guide to the Construction of Radiometallated Bioconjugates for Positron Emission Tomography. Dalton Trans. 2011, 40, 6168–6195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Ramogida CF; Orvig C Tumour Targeting with Radiometals for Diagnosis and Therapy. Chem. Commun. (Cambridge, U. K.) 2013, 49, 4720–4739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Kostelnik TI; Orvig C Radioactive Main Group and Rare Earth Metals for Imaging and Therapy. Chem. Rev 2019, 119, 902− 956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Boros E; Packard AB Radioactive Transition Metals for Imaging and Therapy. Chem. Rev 2019, 119, 870–901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Hao G; N Singh A; Liu W; Sun X PET with Non-Standard Nuclides. Curr. Top. Med. Chem 2010, 10, 1096–1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Müller C; Bunka M; Haller S; Köster U; Groehn V; Bernhardt P; van der Meulen N; Türler A; Schibli R Promising Prospects for 44Sc-/47Sc-Based Theragnostics: Application of 47Sc for Radionuclide Tumor Therapy in Mice. J. Nucl. Med 2014, 55, 1658–1664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Price EW; Orvig C Matching Chelators to Radiometals for Radiopharmaceuticals. Chem. Soc. Rev 2014, 43, 260–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Boros E; Ferreira CL; Cawthray JF; Price EW; Patrick BO; Wester DW; Adam MJ; Orvig C Acyclic Chelate with Ideal Properties for 68Ga PET Imaging Agent Elaboration. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2010, 132, 15726–15733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Fani M; André JP; Maecke HR 68Ga-PET: A Powerful Generator-Based Alternative to Cyclotron-Based PET Radiopharmaceuticals. Contrast Media Mol. Imaging 2008, 3, 53–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Maecke HR; Hofmann M; Haberkorn U 68Ga-Labeled Peptides in Tumor Imaging. J. Nucl. Med 2005, 46, 172S–178S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Hernandez R; Valdovinos HF; Yang Y; Chakravarty R; Hong H; Barnhart TE; Cai W 44Sc: An Attractive Isotope for Peptide-Based PET Imaging. Mol. Pharmaceutics 2014, 11, 2954–2961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Breeman WAP; de Blois E; Sze Chan H; Konijnenberg M; Kwekkeboom DJ; Krenning EP 68Ga-labeled DOTA-Peptides and 68Ga-Labeled Radiopharmaceuticals for Positron Emission Tomography: Current Status of Research, Clinical Applications, and Future Perspectives. Semin. Nucl. Med 2011, 41, 314–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Umbricht CA; Benesova M; Schmid RM; Turler A; Schibli R; van der Meulen NP; Muller C 44Sc-PSMA-617 for Radiotheragnostics in Tandem with 177Lu-PSMA-617—Preclinical Investigations in Comparison with 68Ga-PSMA-11 and 68Ga-PSMA-617. EJNMMI Res. 2017, 7, 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Singh A; van der Meulen NP; Müller C; Klette I; Kulkarni HR; Türler A; Schibli R; Baum RP First-in-Human PET/CT Imaging of Metastatic Neuroendocrine Neoplasms with Cyclotron-Produced 44Sc-DOTATOC: A Proof-of-Concept Study. Cancer Biother.Radiopharm 2017, 32, 124–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Eder M; Schäfer M; Bauder-Wüst U; Hull W-E; Wängler C; Mier W; Haberkorn U; Eisenhut M 68Ga-Complex Lipophilicity and the Targeting Property of a Urea-Based PSMA Inhibitor for PET Imaging. Bioconjugate Chem. 2012, 23, 688–697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Gabriel M; Decristoforo C; Kendler D; Dobrozemsky G; Heute D; Uprimny C; Kovacs P; Von Guggenberg E; Bale R; Virgolini IJ 68Ga-DOTA-Tyr3-Octreotide PET in Neuroendocrine Tumors: Comparison with Somatostatin Receptor Scintigraphy and CT. J. Nucl. Med 2007, 48, 508–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Domnanich KA; Müller C; Benešová M; Dressler R; Haller S; Köster U; Ponsard B; Schibli R; Türler A; van der Meulen NP 47Sc as Useful β−Emitter for the Radiotheragnostic Paradigm: a Comparative Study of Feasible Production Routes. EJNMMI Radiopharm. Chem 2017, 2, 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Połosak M; Piotrowska A; Krajewski S; Bilewicz A Stability of 47Sc-complexes with Acyclic Polyamino-Polycarboxylate Ligands. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem 2013, 295, 1867−1872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Khawar A; Eppard E; Sinnes JP; Roesch F; Ahmadzadehfar H; Kürpig S; Meisenheimer M; Gaertner FC; Essler M; Bundschuh RA [44Sc]Sc-PSMA-617 Biodistribution and Dosimetry in Patients With Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Carcinoma. Clin. Nucl. Med 2018, 43, 323–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Severin GW; Engle JW; Valdovinos HF; Barnhart TE; Nickles RJ Cyclotron Produced 44gSc from Natural Calcium. Appl. Radiat. Isot 2012, 70, 1526–1530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Filosofov DV; Loktionova NS; Rösch FA 44Ti/ 44Sc Radionuclide Generator for Potential Application of 44Sc-Based PETRadiopharmaceuticals. Radiochim. Acta 2010, 98, 149–156. [Google Scholar]

- (22).Nagy G; Szikra D; Trencsényi G; Fekete A; Garai I; Giani AM; Negri R; Masciocchi N; Maiocchi A; Uggeri F; Tóth I; Aime S; Giovenzana GB; Baranyai Z AAZTA: An Ideal Chelating Agent for the Development of 44Sc PET Imaging Agents. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2017, 56, 2118–2122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Li L; Jaraquemada-Peláez M. d. G.; Kuo H-T; Merkens H; Choudhary N; Gitschtaler K; Jermilova U; Colpo N; Uribe-Munoz C; Radchenko V; Schaffer P; Lin KS; Bénard F; Orvig C Functionally Versatile and Highly Stable Chelator for 111In and 177Lu: Proof-of-Principle Prostate-Specific Membrane Antigen Targeting. Bioconjugate Chem. 2019, 30, 1539–1553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Haberkorn U; Eder M; Kopka K; Babich JW; Eisenhut M New Strategies in Prostate Cancer: Prostate-Specific Membrane Antigen (PSMA) Ligands for Diagnosis and Therapy. Clin. Cancer Res 2016, 22, 9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Maresca KP; Hillier SM; Femia FJ; Keith D; Barone C; Joyal JL; Zimmerman CN; Kozikowski AP; Barrett JA; Eckelman WC; Babich JW A Series of Halogenated Heterodimeric Inhibitors of Prostate Specific Membrane Antigen (PSMA) as Radiolabeled Probes for Targeting Prostate Cancer. J. Med. Chem 2009, 52, 347–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Benešová M; Bauder-Wüst U; Schäfer M; Klika KD; Mier W; Haberkorn U; Kopka K; Eder M Linker Modification Strategies To Control the Prostate-Specific Membrane Antigen (PSMA)-Targeting and Pharmacokinetic Properties of DOTA-Conjugated PSMA Inhibitors. J. Med. Chem 2016, 59, 1761–1775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Benešová M; Schäfer M; Bauder-Wüst U; Afshar-Oromieh A; Kratochwil C; Mier W; Haberkorn U; Kopka K; Eder M Preclinical Evaluation of a Tailor-Made DOTA-Conjugated PSMA Inhibitor with Optimized Linker Moiety for Imaging and Endoradiotherapy of Prostate Cancer. J. Nucl. Med 2015, 56, 914–920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Kratochwil C; Bruchertseifer F; Giesel FL; Weis M; Verburg FA; Mottaghy F; Kopka K; Apostolidis C; Haberkorn U; Morgenstern A 225Ac-PSMA-617 for PSMA-Targeted α-Radiation Therapy of Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. J. Nucl. Med 2016, 57, 1941−1944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Shannon RD Revised Effective Ionic Radii and Systematic Studies of Interatomic Distances in Halides and Chalcogenides. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. A: Cryst. Phys., Diffr., Theor. Gen. Crystallogr 1976, 32, 751–767. [Google Scholar]

- (30).Wang X; Jaraquemada-Peláez M. d. G.; Rodríguez-Rodríguez C; Cao Y; Buchwalder C; Choudhary N; Jermilova U; Ramogida CF; Saatchi K; Häfeli UO; Patrick BO; Orvig C H4octox: Versatile Bimodal Octadentate Acyclic Chelating Ligand for Medicinal Inorganic Chemistry. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2018, 140, 15487–15500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Gans P; Sabatini A; Vacca A Investigation of Equilibria in Solution. Determination of Equilibrium Constants with the HYPER-QUAD Suite of Programs. Talanta 1996, 43, 1739–1753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Gans P; Sabatini A; Vacca A Determination of equilibrium constants from spectrophometric data obtained from solutions of known pH: The program pHab. Anal. Chim 1999, 89, 45–49. [Google Scholar]

- (33).Pniok M; Kubíček V; Havlíčková J; Kotek J; Sabatie- Gogová A; Plutnar J; Huclier-Markai S; Hermann P Thermodynamic and Kinetic Study of Scandium(III) Complexes of DTPA and DOTA: A Step Toward Scandium Radiopharmaceuticals. Chem. - Eur. J 2014, 20, 7944–7955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Baes CF Jr.; Mesmer RE The Hydrolysis of Cations; John Wiley & Sons: New York, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- (35).Lindqvist-Reis P; Persson I; Sandström M The Hydration of the Scandium(III) Ion in Aqueous Solution and Crystalline Hydrates Studied by XAFS Spectroscopy, Large-Angle X-Ray Scattering and Crystallography. Dalton Trans. 2006, 32, 3868–3878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Pruszyński M; Majkowska-Pilip A; Loktionova NS; Eppard E; Roesch F Radiolabeling of DOTATOC with the Long-Lived Positron Emitter 44Sc. Appl. Radiat. Isot 2012, 70, 974–979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Fendler WP; Stuparu AD; Evans-Axelsson S; Lückerath K; Wei L; Kim W; Poddar S; Said J; Radu CG; Eiber M; Czernin J; Slavik R; Herrmann K Establishing 177Lu-PSMA-617 Radioligand Therapy in a Syngeneic Model of Murine Prostate Cancer. J. Nucl. Med 2017, 58, 1786–1792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Lee C; Yang W; Parr RG Development of the Colle-Salvetti Correlation-Energy Formula into a Functional of the Electron Density. Phys. Rev. B: Condens. Matter Mater. Phys 1988, 37, 785− 789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Becke AD Density-Functional Exchange-Energy Approximation with Correct Asymptotic Behavior. Phys. Rev. A: At., Mol., Opt. Phys 1988, 38, 3098–3100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Alliot C; Kerdjoudj R; Michel N; Haddad F; Huclier-Markai S Cyclotron Production of High Purity 44m,44Sc with Deuterons from 44CaCO3 Targets. Nucl. Med. Biol 2015, 42, 524–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Hay PJ; Wadt WR Ab Initio Effective Core Potentials for Molecular Calculations. Potentials for K to Au Including the Outermost Core Orbitals. J. Chem. Phys 1985, 82, 299–310. [Google Scholar]

- (42).Hay PJ; Wadt WR Ab Initio Effective Core Potentials for Molecular Calculations. Potentials for the Transition Metal Atoms Sc to Hg. J. Chem. Phys 1985, 82, 270–283. [Google Scholar]

- (43).Gran G Determination of the Equivalence Point in Potentiometric Titrations. Part II. Analyst 1952, 77, 661–671. [Google Scholar]

- (44).Paul MA; Long FA H0 And Related Indicator Acidity Function. Chem. Rev 1957, 57, 1–45. [Google Scholar]

- (45).Vickery RC 348. Lanthanon Complexes with Ethylenediamine-NNN′N-tetra-acetic Acid. Part III. J. Chem. Soc 1952, 0, 1895–1898. [Google Scholar]

- (46).Harris WR; Carrano CJ; Raymond KN Spectrophotometric Determination of the Proton-Dependent Stability Constant of Ferric Enterobactin. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1979, 101, 2213–2214. [Google Scholar]

- (47).Hernandez R; Sun H; England CG; Valdovinos HF; Ehlerding EB; Barnhart TE; Yang Y; Cai W CD146-Targeted ImmunoPET and NIRF Imaging of Hepatocellular Carcinoma with a Dual-Labeled Monoclonal Antibody. Theranostics 2016, 6, 1918− 1933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.