Abstract

Background

Numerous studies have shown that long noncoding RNAs play important roles in human cancer progression. Although zebrafish xenografts have recently become a novel in vivo model for human cancer research, whether such models can be used to study the function of long noncoding RNAs remains unknown.

Methods

In vitro studies validated the roles of LINC00152 in the proliferation and invasion of lung cancer cells. In vivo studies of zebrafish xenografts also confirmed these roles of LINC00152. In vivo confocal imaging was used to more accurately evaluate the function of LINC00152 in cell proliferation and migration. Pharmacological experiments were further performed to study the potential ability of LINC00152 downregulation combined with an EGFR inhibitor to treat tumors in cultured cells and the zebrafish xenograft model.

Results

Silencing of LINC00152 suppressed cell proliferation and invasion in SPCA1 and A549 lung cancer cell lines in vitro. In the zebrafish xenograft model, knockdown of LINC00152 reduced the proliferation and migration of lung cancer cells, as indicated by the two imaging methods at different magnifications. Moreover, the knockdown of LINC00152 enhanced the inhibition effect of afatinib for lung cancer progression in cultured cells and the zebrafish xenograft model.

Conclusion

Our study reveals the oncogenic roles and potential for LINC00152 to be a target for tumor treatment in lung cancer using zebrafish xenograft models, and the findings suggest that this model could be used for functional and application studies of human long noncoding RNAs in tumor biology.

Keywords: LINC00152, Zebrafish xenograft, Afatinib, EGFR, Lung cancer

Background

Zebrafish xenografts have become an increasingly popular animal model for human cancer research in the last decade [1]. Thus far, different types of zebrafish xenografts have been established, such as melanoma, colorectal cancer, and breast cancer xenografts [1–5], and zebrafish patient derived xenograft (zPDX) models have also been generated by transplanting hundreds of cells from human tumor tissue with a high success rate [3, 5–8]. The relative stemness and immature immune environment of zebrafish larvae represent proper conditions for the growth of human cancer cells [9]. Compared with the mouse xenograft model, the transparent zebrafish larvae xenograft model offers the speed and intuitiveness for studies on the cellular resolution level with relatively large samples [1, 7, 8], which would contribute to the study of tumor biology. Thus, developing reliable zebrafish xenografts has become increasingly important for tumor research and personalized clinical testing.

Bioinformatics analyses with whole-genome sequencing data show that protein-coding sequences account for less than 3% of the human genome and most of the transcripts are noncoding RNA, such as tRNA, rRNA, miRNA and long noncoding RNA (lncRNA) [10]. lncRNAs are a class of transcripts longer than 200 nucleotides with limited protein coding potential [11]. Recent studies showed that lncRNAs play critical roles in proliferation, differentiation, metastasis, metabolism, and apoptosis in cancer progression by regulating the expression of protein-coding genes at the transcriptional, posttranscriptional and epigenetic levels [12–16]. Thus far, only lncRNA THOR has been reported to have an oncogenic role in tumorigenesis via a zebrafish model [17]. However, the homologies of most human lncRNAs cannot be found in zebrafish, which limits the application of zebrafish genetic models for tumor-related lncRNA research [18]. Zebrafish xenograft models offer the in vivo conditions of human cancer cells and do not have such restrictions, which prompts us to explore whether such models can be used to study the roles of human lncRNAs in cancer.

Long intergenic noncoding RNA 00152 (LINC00152) was first reported to be highly expressed in human gastric cancer tissues and cells [19], and it is located on chromosome 2p11.2 and has a transcript length of 828 nucleotides. Further studies also found that LINC00152 was overexpressed in gallbladder cancer, clear cell renal cell carcinoma, glioma, lung adenocarcinoma, etc., and it is involved in cell proliferation, invasion and apoptosis [20–25]. These studies showed that LINC00152 regulates tumor progression via signaling pathways, which indicates that LINC00152 might have a common oncogenic role in different human cancers [20, 23, 26–30]. In lung cancer, LINC00152 is highly expressed at ~ 2.63-fold, and its expression is associated with poor prognosis for lung adenocarcinoma patients [23, 31]. Considering its importance, we have attempted to validate its roles by using zebrafish lung cancer xenograft models.

In this study, we first verified the function of LINC00152 in cell proliferation and invasion in two lung cancer cell lines. Then, zebrafish xenografts are evaluated via stereomicroscopy to validate the oncogenic role of LINC00152 in vivo. By confocal imaging experiments, we more precisely confirmed LINC00152’s function. Furthermore, we studied the antitumor effect of the combination of LINC00152 knockdown and EGFR inhibition and found that LINC00152 and EGFR had synergetic effects for lung cancer treatment.

Materials and methods

Zebrafish

Adult zebrafish were maintained in a fish auto culture system (Haishen, China) at 28 °C under a 14–10 h light–dark cycle. Embryos were raised in 10% Hank’s solution that consisted of (in mM) 140 NaCl, 5.4 KCl, 0.25 Na2HPO4, 0.44 KH2PO4, 1.3 CaCl2, 1.0 MgSO4 and 4.2 NaHCO3 (pH 7.2). The zebrafish AB wildtype and transgenic line Tg(fli1a:EGFP) were used in our study [32]. Zebrafish handling procedures were approved by Nanjing Medical University.

Cell culture

The human nonsmall cell lung cancer cell lines A549, H1299, H1975, SPCA1, PC9 and human bronchial epithelial cells 16HBE were obtained from Institute of Biochemistry and Cell Biology of Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanghai, China). A549, H1975 and 16HBE cells were cultured in 1640 medium; and H1299, SPCA1 and PC9 cells were cultured in DMEM. Both media were supplemented with 10% FBS (Sciencell, USA), 100 µ/ml penicillin, and 100 µ/ml streptomycin, and then cultured in a humidified air atmosphere containing 5% CO2 at 37 °C.

RNA extraction and qRT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from cell lines using TRIzol reagent. Total RNA was reverse transcribed to cDNA using 1st Strand cDNA Synthesis SuperMix for qPCR kit (Takara, Dalian, China). We performed quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR) analyses using SYBR Green Master Mix kit (Takara) following the manufacturer’s instructions to detect the expression levels of LINC00152 in different lung cancer cell lines. Data were analyzed based on the 2−∆∆CT method, and glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was used as the internal control. The primer sequences of LINC00152 were as follows: forward 5′-CACTGAAAATCACGACTCC-3′ and reverse 5′-AAATGGGAAACCGACCAGAC-3′. The primer sequences for GAPDH were as follows: forward 5′-GGGAGCCAAAAGGGTCAT-3′ and reverse 5′-GAGTCCTTCCACGATACCAA-3′.

RNA interference

LINC00152 small interfering RNA (siRNA) and negative control siRNA were purchased from General Biosystems (China). A549 and SPCA1 cell lines were cultured in six-well plates, and then specific siRNAs were transfected into A549 and SPCA1 cell lines after 24 h using Lipofectamine 3000 reagents (Invitrogen, USA). The LINC00152 siRNA sequence is 5′-TGATCGAATATGACAGACACCGAAA-3′, and the negative control siRNA sequences are 5′-TTCTCCGAACGTGTCACGT-3′. Cells were harvested after transfection for 24 h, and knockdown efficiency was then quantified by qRT-PCR.

Cell proliferation assay

Cell proliferation assay were performed using a Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8, DOJINDO, Japan). LINC00152 siRNA and negative control siRNA were transfected into A549 and SPCA1 cell lines, which were then seeded in 96-well plates after transfection for 24 h. A total of 2 × 103 cells were seeded in each well of 96-well plates. Cell proliferation was monitored on a microplate reader (BioTek Elx800, USA) by measuring the optical density at 450 nm every 24 h from 0 to 72 h according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and then data of each group were analyzed.

Transwell assays

A549 and SPCA1 were transfected with LINC00152 siRNA and negative control siRNA. After 24 h of transfection, transfected cells were seeded in 24-well plates with 8-mm-pore size chamber inserts. Then, 4–5 × 104 cells were plated into the upper chambers, which were diluted with serum-free culture medium. The upper chambers were then placed into the lower chambers of 24-well plates that included 800 μl medium with 10% FBS. After 24 h, the cells migrated to the bottom surface of the membrane, and then the cells were fixed with methanol and stained with 0.1% crystal violet for 30 min. The images were collected under an inverted microscope.

Zebrafish xenograft injection

Cultured cancer cells were labeled with CM-DiI (Invitrogen, USA) before injection. Cultured cells were first collected and then washed three times with HBSS. Next, the cells were labeled with CM-DiI at 37 °C for 5 min, following by 15 min at 4 °C, and unincorporated dye was removed by rinsing three times with HBSS. The cells were then examined via fluorescence microscopy. Subsequently, 2-days-postfertilization (dpf) zebrafish larvae were mounted using 1.2% low-melting gel (Promega, USA), and then approximately 400 CM-DiI labeled cells were injected into the perivitelline space (PVS) of each larvae under a microinjector (Picosprizer III, USA). After injection, the xenografts were cultured at 34 °C. At 24 h postinjection (hpi), the zebrafish larvae with similar sizes of transplanted cells were collected for further analysis and then cultured at 34 °C until the end of experiments.

In vivo imaging and quantitative analysis

At 4 days postinjection (dpi), the zebrafish larvae were also mounted using 1.2% low-melting gel for the imaging experiments. Imaging experiments were performed via stereomicroscope (MVX10, Olympus, Japan) or confocal microscope using a 20X water-immersion objective (Fluoview 1000, Olympus, Japan). The spatial resolution of the images was 1600 × 1200 (MVX10) or 1024 × 1024 pixels (Fluoview 1000).

Drug administration

After 24-h transfection, the cells were seeded in 96-well plates and cultured in medium containing 2 nM afatinib (Selleck, China), and then cell proliferation was quantified by CCK-8. Transfected cells were also plated into the upper chambers, and the medium in the lower chambers contained 2 nM afatinib. Then, cell invasion was quantified. In the zebrafish xenografts, the 24-hpi zebrafish xenografts with a similar tumor size were randomly divided in two groups: Hank’s solution and Hank’s solution containing 1 nM afatinib. These larvae were raised for three consecutive days (3 days posttreatment, dpt) and then mounted for the imaging experiments.

Statistics

Statistical analyses were performed using unpaired Student’s t-tests. P values less than 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant. All results are represented as the mean ± SEM.

Results

Knockdown of LINC00152 suppressed lung cancer cell proliferation and invasion in vitro

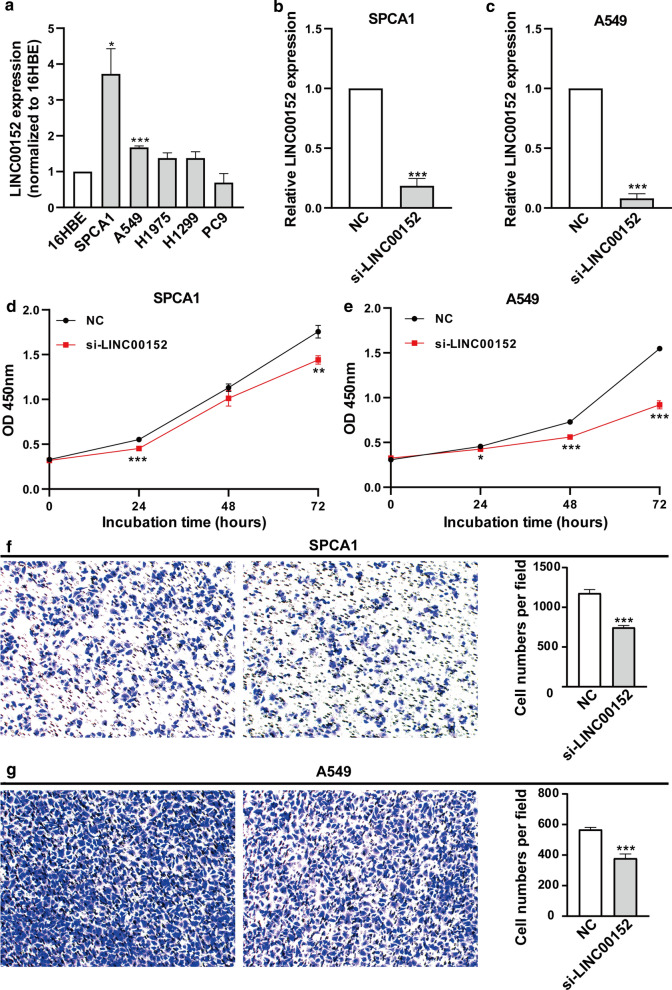

We first examined the LINC00152 expression level in five human lung cell lines using qRT-PCR via comparisons with the human bronchial epithelial cell line 16HBE. Among these cell lines, we found LINC00152 were highly expressed in the SPCA1 and A549 cell lines, and the values were 1.7 ~ 3.7-fold higher than that of the 16HBE line (Fig. 1a). To investigate the roles of LINC00152 in A549 and SPCA1, we tried to silence its expression in the two cell lines. According to the reported knockdown data of the three siRNAs [23], we synthesized one of the siRNAs with the highest silence efficiency and transfected it in SPCA1 and A549 cells. After 48 h posttransfection, we observed that the knockdown efficiency of LINC00152 was 81.5% in SPCA1 cells and 91.9% in A549 cells compared with the negative control siRNA (Fig. 1b, c). Next, we examined the cell viability using a CCK-8 assay and found that the viability of SPCA1 and A549 cells were significantly decreased when knocking down LINC00152 (Fig. 1d, e). Further, we examined cell invasion by transwell assays. We found that the knockdown of LINC00152 in SPCA1 and A549 cells also significantly repressed cell invasion compared with the control (Fig. 1f, g). These results verified the oncogenic roles of LINC00152 in the two lung cancer cell lines, suggesting that we could perform further in vivo tests in zebrafish xenografts using this siRNA-mediated knockdown strategy.

Fig. 1.

Knockdown of LINC00152 decreases the proliferation and invasion of lung cancer cells in vitro. a LINC00152 expression was analyzed by qRT-PCR in 5 NSCLC cell lines that were compared with the normal human bronchial epithelial cell line (16HBE). b, c LINC00152 mRNA levels in SPCA1 (b) and A549 (c) with LINC00152 siRNA (si-LINC00152) transfection compared with the negative control siRNA (NC) by qRT-PCR. d, e CCK-8 assays were performed to detect the viability of SPCA1 (d) and A549 (e) with LINC00152 siRNA transfection. f, g Transwell assays were performed to detect the invasion of SPCA1 (f) and A549 (g) with LINC00152 siRNA transfection. *: p < 0.05, **: p < 0.01, ***: p < 0.001

Knockdown of LINC00152 suppressed lung cancer cell proliferation and invasion in the zebrafish xenograft model based on stereomicroscopy

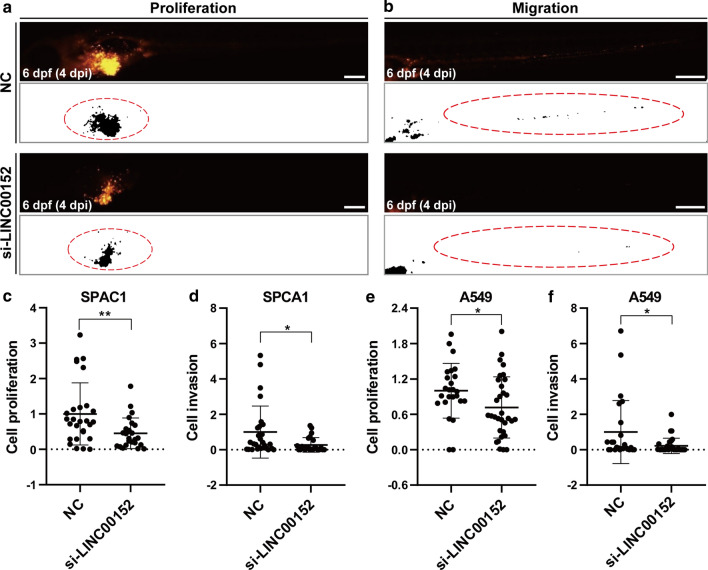

To determine whether the knockdown of LINC00152 by siRNA affects tumorigenesis of lung cancer in zebrafish xenograft model, we transplanted the SPCA1 and A549 cells with LINC00152 siRNA transfection into zebrafish embryos. After 24 h posttransfection of siRNA, lung cancer cells were labeled with fluorescent dye (CM-DiI) and then approximately 400 cells were inoculated into the PVS of 2-dpf zebrafish larvae. To evaluate the tumor progression, we collected samples with similar tumor sizes via fluorescence stereomicroscopy from all the transplanted zebrafish larvae at 1 dpi, and these selected samples were then cultured. At 4 dpi, the yolk and trunk of the selected zebrafish larvae samples were photographed. We quantified the area with CM-DiI positive signals, which represented the tumor area in the yolk and trunk (Fig. 2a, b) [3, 33]. Compared with the control group, we found that the CM-DiI-positive area was significantly smaller in the yolk and trunk when knocking down the LINC00152 in SPCA1 cells (Fig. 2c, d), indicating that knockdown of LIN00152 decreased the proliferation (in yolk) and invasion (in trunk) of SPCA1 cells. Similar results were also observed in the A549 cells (Fig. 2e, f). These results are consistent with the data in cultured cells, indicating that the zebrafish xenograft model can be used for functional studies of LINC00152 in lung cancer by siRNA-mediated knockdown strategies.

Fig. 2.

Knockdown of LINC00152 decreases the proliferation and invasion of lung cancer cells in zebrafish xenograft by stereomicroscopy. a, b Lung cancer cells transfected with si-LINC00152 siRNA or NC were injected into the PVS of 2-dpf WT zebrafish larvae. Images were taken using a stereomicroscope at 4 dpi. CM-DiI-positive areas in the yolk were quantified for proliferation (a), and CM-DiI-positive areas in trunk were quantified for invasion (b). The regions enclosed by the red dashed curve in the segmented images were selected for calculating tumor areas in the yolk or trunk. c, d Statistical analysis of proliferation (c) and invasion (d) when knocking down LINC00152 in SPCA1 cells. e, f Statistical analysis of proliferation (c) and invasion (d) when knocking down LINC00152 in A549 cells. *: p < 0.05, **: p < 0.01. Scale: 250 μm

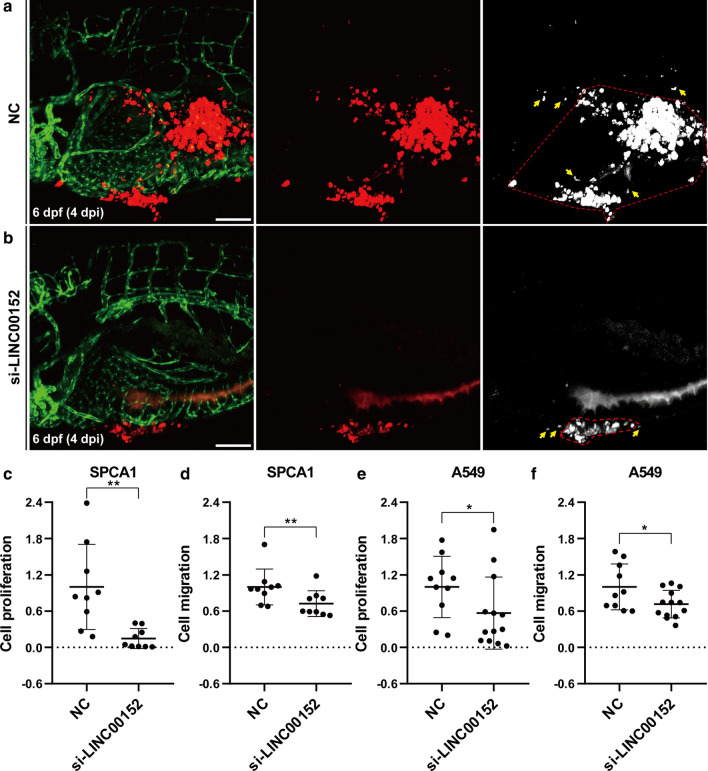

Knockdown of LINC00152 suppressed lung cancer cell proliferation and migration in the zebrafish xenograft model by confocal microscopy

During the imaging experiments using the stereomicroscope, we found that the CM-DiI-positive signal might not always represent the tumor cells because nonspecific fluorescence signals were observed in the yolk of the zebrafish larvae. In addition, only a few of the transplanted SPCA1 or A549 cells were observed in the trunk of the larvae, which meant that the two cells had limited invasion levels in the zebrafish xenograft and additional samples must be analyzed to increase the credibility of the data. Thus, we used confocal microscope to obtain high-resolution images with few nonspecific signals and then analyzed the proliferation and migration in the yolk. To simultaneously examine the tumor progression and angiogenesis, CM-DiI labeled lung cancer cells were injected into Tg(fli1a:EGFP) zebrafish larvae in which the vascular endothelial cells are labeled by EGFP, and then the xenografts were imaged by multiple-layer scanning at 4 dpi (Fig. 3a, b). In these confocal images, we also found a few separate CM-DiI-positive spots that could not be identified as cancer cells because the size of spots was much smaller than the cells (right in Fig. 2a, b). We quantified the area of CM-DiI-positive cells by removing the noncell spots in the yolk and then comparing the LINC00152 siRNA transfected group with the NC transfected group in the SPCA1 cells. We found that the knockdown of LINC00152 decreased the cell proliferation significantly (Fig. 3c). To analyze the cell migration in the yolk, we first quantified the cancer cell coverage area by calculating the area of polygon formed by connecting lines of peripheral cancer cell points, which represented the total range of cell migration. To avoid the effects caused by the number of total cancer cells, we quantified cell migration by dividing the cell coverage area by the tumor area. We found that the knockdown of LINC00152 significantly decreased the migration of SPCA1 cells in the yolk of zebrafish larvae (Fig. 3d). Similar results were also observed in the A549-cell transplanted larvae (Fig. 3e, f). These results confirm that the zebrafish xenograft model can be used for functional studies of LINC00152 in lung cancer.

Fig. 3.

Knockdown LINC00152 decreases the proliferation and invasion of lung cancer cells in zebrafish xenograft by confocal microscopy. a, b Lung cancer cells transfected with si-LINC00152 (a) or NC (b) were injected into the PVS of 2-dpf Tg(fli1a:EGFP) transgenic zebrafish larvae. Images were taken by confocal microscope at 4 dpi. Tumor areas in the yolk were quantified for proliferation, and the polygons enclosed by red dashed lines represent the tumor cell covering areas. The yellow arrow represents cell debris, which is excluded from the tumor cell covering areas. c, d Statistical analysis of proliferation (c) and migration (d) when knocking down LINC00152 in SPCA1 cells. e, f Statistical analysis of proliferation (e) and migration (f) when knocking down LINC00152 in A549 cells.*: p < 0.05, **: p < 0.01. Scale: 100 μm

Knockdown of LINC00152 and blocking of EGFR have a synergetic effect on the inhibition of proliferation and invasion of lung cancer in vitro

Next, we tested the possibility of LINC00152 as a treatment target of lung cancer. EGFR is one of the critical therapeutic targets in NSCLC lung cancer, and the A549 cell line is sensitive to different types of EGFR inhibitors [34, 35]. The knockdown of LINC00152 has been reported to decrease EGFR expression, which indicates that LINC00152 might regulate cancer progression via the EGFR pathway [36]. Accordingly, we first examined the viability of A549 cells when blocking EGFR by afatinib and found that cell viability was significantly decreased, which was similar to the effect of knockdown of LINC00152 (Fig. 4a). We also noticed that knockdown of LINC00152 led to an earlier inhibition effect than afatinib treatment in A549 cells, which implied that LINC00152 could be upstream of the EGFR pathway. Moreover, simultaneous knockdown of LINC00152 and treatment with afatinib could enhance the inhibition effect (Fig. 4a). A transwell assay also found enhanced inhibition of invasion in A549 cells (Fig. 4b, c). These results imply silencing of LINC00152 and blocking of EGFR might have a synergetic effect in lung cancer progression.

Fig. 4.

Knocking down LINC00152 and blocking EGFR have a synergic effect on the inhibition of cell proliferation and invasion in vitro. a CCK-8 assays were performed to detect the viability of A549 with NC transfection, NC transfection and afatinib (EGFR inhibitor) administration, si-LINC00152 transfection, si-LINC00152 transfection and afatinib administration. b Transwell assays were used to investigate invasion with NC or si-LINC00152 transfection and afatinib administration or not. c Statistical analysis of invasion with NC or LINC00152 siRNA transfection and afatinib administration or not. ns, not statistically significant, **: p < 0.01, ***: p < 0.001

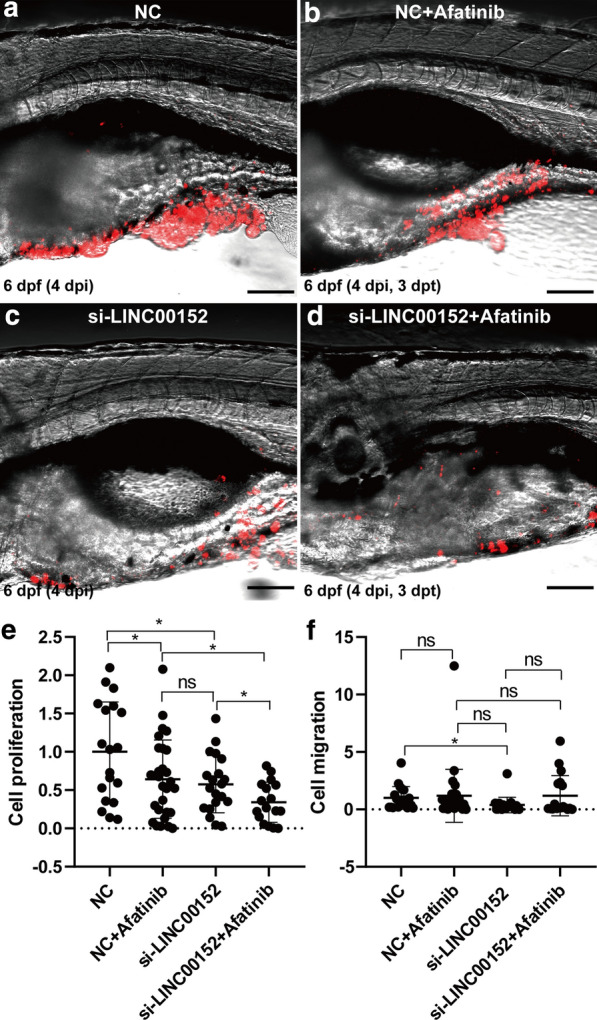

Knockdown of LINC00152 and blocking of EGFR have a synergetic effect on the inhibition of proliferation in zebrafish xenograft model

We also tested the possibility of using LINC00152 for clinical application in zebrafish xenograft models. In addition to knockdown of LINC00152 in zebrafish xenografts, we also bathed afatinib in zebrafish culture medium (Fig. 5a–d). In the cultured cells, knockdown of LINC00152 also enhanced the inhibition effect of afatinib on cell proliferation in zebrafish lung cancer xenograft models (Fig. 5e). However, we did not observe enhanced inhibition of invasion when combining knockdown of LINC00152 and afatinib treatment (Fig. 5f). These results suggest that LINC00152 and EGFR might be clinical combined therapy targets for lung cancer.

Fig. 5.

Knockdown of LINC00152 and block of EGFR have a synergic effect of inhibition in cell proliferation in zebrafish xenograft. a-d Lung cancer cells with NC transfection (a, b) or si-LINC00152 transfection were injected into the PVS of 2-dpf WT zebrafish larvae, and afatinib was bathed in zebrafish culture medium (b, d) or not (a, c). Images were taken by a confocal microscope at 3 dpt. e, f Statistical analysis of the proliferation and invasion with NC or LINC00152 siRNA transfection and afatinib administration or not. ns, not statistically significant, *: p < 0.05. Scale: 100 μm

Discussion

Recent reports have indicated that LINC00152 plays important roles in the progression of lung cancer [23, 31, 37]. Further studies revealed that LINC00152 regulates the cell cycle of lung cancer through different signal pathways [23, 31]. In the present study, we verified that LINC00152 played an oncogenic role in cell proliferation and invasion in vitro. We also showed that knockdown of LINC00152 decreased the proliferation and migration of lung cancer cells in zebrafish xenograft models by two imaging experiments with different resolutions. Moreover, pharmacological experiments also indicated that LINC00152 and EGFR have synergistic effects on anti-tumor treatment in vitro and in vivo. These findings suggest that the zebrafish xenograft model could represent a new in vivo model for the functional study of human lncRNA.

Mouse xenografts are used for tumor biology for decades [38]. Previous studies also reported that LINC00152 promotes lung cancer proliferation and invasion in mouse xenograft models [23, 31]. At 18 days after subcutaneous injection in nude mice, A549 cells stably transfected with LINC00152 shRNA showed decreased tumor size and tumor weight, and immunohistochemical analyses showed a lower proliferation level in the LINC00152 silenced group than the control [23]. At 28 days after tail vein injection in nude mice, the metastatic cancer lesions in lung and liver tissue formed in the control mice but could not be detected in the LINC00152 silenced group [31]. Consistent with these results, our present study found that knockdown of LINC00152 decreased the proliferation and invasion of lung cancer cells in zebrafish xenograft models. These data suggest that zebrafish xenografts could be a reliable cancer model for human lncRNA functional studies.

Zebrafish xenografts not only offer an alternative strategy for in vivo studies but also show great promise in tumor biology. First, the zebrafish xenografts in the present study only could be evaluated 4 days after transplantation to determine the proliferation and invasion of tumor cells, whereas mouse xenografts require 2–4 weeks and stable shRNA transfection cells must be generated because the knockdown effect by siRNA transfection does not persist over such time periods. Second, different models are required to study proliferation and invasion in mouse xenografts, whereas different tumor cell distributions can be assessed throughout the body of zebrafish larvae using zebrafish xenografts; thus, proliferation and migration can be analyzed simultaneously. Additional parameters of tumor cells could be further analyzed, such as tissue-specific invasion and proliferation. Third, transparent zebrafish xenografts offer high-resolution cell observations, which means that fine tumor cell behavior can be detected in vivo. Combining transgenic lines that label different cell types, zebrafish xenografts offer good models for studying the relationship between tumor cells and different cells in vivo [2]. With the help of fast and high-resolution microscopy, timely and three-dimensional in vivo imaging has been achieved for observing the process of tumor cell metastasis in zebrafish larva [39]. In our study, we also evaluated vascular growth in the zebrafish lung cancer xenograft, although obvious changes in angiogenesis at the tumor sites were not observed, which indicated that the two lung cancer cell lines might not present obvious changes in vascular growth in our observation windows (Fig. 3a, b). Finally, the cost of zebrafish xenografts is much lower than that of mouse xenografts, which makes it possible to analyze larger samples for obtaining more accurate data for cancer research.

During the process of studying the zebrafish xenograft, we noticed that CM-DiI-positive signals do always represent tumor cells and may indicate the debris of cancer cells, such as apoptotic bodies, exosomes, etc., which would affect the accuracy when evaluating cell proliferation and invasion. In our study, a high-resolution imaging strategy can reduce the related impact, and we will attempt to improve it by florescent protein-expressing cell transplantation in further studies. Zebrafish larvae show a high success rate for generating xenograft models, even PDX models, although the relative stemness environment for cancer cells might be different from the conditions in human patients. Immune-deficient and transparent adult zebrafish models are also developed to generate xenograft models, which could improve the application of such xenografts in tumor biology [5]. In total, zebrafish xenografts offer rapid and intuitive models that represent a complementary and optimized model relative to mouse models. The development of the reliable analysis methods will expand the applications in basic and clinical research.

Drug testing using in vivo model is very critical for personalized therapy. Zebrafish xenografts can be proper models because easily drug administration and short evaluation time. In our study, pharmacological experiments indicated that LINC00152 might be a combination therapy target with EGFR for lung cancer. Moreover, a few of studies have been reported that zPDX model can be constructed that could be produced considerable amount of xenograft samples for personalized drug testing before clinical treatment [3, 5–8]. Although more studies are required for collecting the evidence of the consistency between human tumor and zPDX models, the zPDX model might represent a more feasible method than mouse models for personalized therapy.

Conclusions

In summary, our results demonstrated the oncogenic effect of LINC00152 in zebrafish xenograft in vivo models. Additionally, pharmacological experiments indicated that knocking down LINC00152 and blocking EGFR have synergic effects on inhibiting lung cancer progression. Our study suggests that zebrafish xenografts represent a rapid and intuitive in vivo cancer model for lncRNA research.

Acknowledgements

We thank Prof. Wei De from Nanjing Medical University for providing helpful discussions. We thank Nanjing XinJia Medical Technology Co., Ltd. for helping with zebrafish xenograft construction.

Abbreviations

- CCK-8

Cell Counting Kit-8

- dpf

Days postfertilization

- dpi

Days postinjection

- dpt

Days posttreatment

- GAPDH

Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- hpi

Hours postinjection

- LINC00152

Long intergenic noncoding RNA 00152

- lncRNA

Long noncoding RNA

- PVS

Perivitelline space

- qRT-PCR

Quantitative reverse transcription-PCR

- siRNA

Small interfering RNA

- zPDX

Zebrafish patient derived xenograft

Authors’ contributions

YZ conceived the project. WS, JP and YZ designed the experiments. WS, JP, JS and BT performed the cell culture and drug administration experiments. WW, LW and JC performed the zebrafish transplant experiments. WS, JP analyzed all results. WS wrote the manuscript with inputs from JP and YZ. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

None.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All animal studies were approved by the Ethics Committee and carried out in compliance with the Medicine Institutional Guidelines of Nanjing Medical University.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Wenyi Shen and Juan Pu contributed equally to this work

References

- 1.Hason M, Bartunek P. Zebrafish models of cancer-new insights on modeling human cancer in a non-mammalian vertebrate. Genes. 2019;10(11):935. doi: 10.3390/genes10110935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhao C, Wang X, Zhao Y, Li Z, Lin S, Wei Y, Yang H. A novel xenograft model in zebrafish for high-resolution investigating dynamics of neovascularization in tumors. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(7):e21768. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fior R, Povoa V, Mendes RV, Carvalho T, Gomes A, Figueiredo N, Ferreira MG. Single-cell functional and chemosensitive profiling of combinatorial colorectal therapy in zebrafish xenografts. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2017;114(39):E8234–E8243. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1618389114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eguiara A, Holgado O, Beloqui I, Abalde L, Sanchez Y, Callol C, Martin AG. Xenografts in zebrafish embryos as a rapid functional assay for breast cancer stem-like cell identification. Cell Cycle. 2011;10(21):3751–3757. doi: 10.4161/cc.10.21.17921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yan C, Brunson DC, Tang Q, Do D, Iftimia NA, Moore JC, Hayes MN, Welker AM, Garcia EG, Dubash TD, et al. Visualizing engrafted human cancer and therapy responses in immunodeficient zebrafish. Cell. 2019;177(7):1903–1914 e1914. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mercatali L, La Manna F, Groenewoud A, Casadei R, Recine F, Miserocchi G, Pieri F, Liverani C, Bongiovanni A, Spadazzi C, et al. Development of a patient-derived xenograft (PDX) of breast cancer bone metastasis in a zebrafish model. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17(8):1375. doi: 10.3390/ijms17081375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wu JQ, Zhai J, Li CY, Tan AM, Wei P, Shen LZ, He MF. Patient-derived xenograft in zebrafish embryos: a new platform for translational research in gastric cancer. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2017;36(1):160. doi: 10.1186/s13046-017-0631-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang L, Chen H, Fei F, He X, Sun S, Lv K, Yu B, Long J, Wang X. Patient-derived heterogeneous xenograft model of pancreatic cancer using zebrafish larvae as hosts for comparative drug assessment. J Vis Exp. 2019;146:e59507. doi: 10.3791/59507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jiang Y, Wells A, Sylakowski K, Clark AM, Ma B. Adult stem cell functioning in the tumor micro-environment. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(10):2566. doi: 10.3390/ijms20102566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carninci P, Kasukawa T, Katayama S, Gough J, Frith MC, Maeda N, Oyama R, Ravasi T, Lenhard B, Wells C, et al. The transcriptional landscape of the mammalian genome. Science. 2005;309(5740):1559–1563. doi: 10.1126/science.1112014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nagano T, Fraser P. No-nonsense functions for long noncoding RNAs. Cell. 2011;145(2):178–181. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ginger MR, Shore AN, Contreras A, Rijnkels M, Miller J, Gonzalez-Rimbau MF, Rosen JM. A noncoding RNA is a potential marker of cell fate during mammary gland development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103(15):5781–5786. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600745103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rinn JL, Kertesz M, Wang JK, Squazzo SL, Xu X, Brugmann SA, Goodnough LH, Helms JA, Farnham PJ, Segal E, et al. Functional demarcation of active and silent chromatin domains in human HOX loci by noncoding RNAs. Cell. 2007;129(7):1311–1323. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dinger ME, Amaral PP, Mercer TR, Pang KC, Bruce SJ, Gardiner BB, Askarian-Amiri ME, Ru K, Solda G, Simons C, et al. Long noncoding RNAs in mouse embryonic stem cell pluripotency and differentiation. Genome Res. 2008;18(9):1433–1445. doi: 10.1101/gr.078378.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cesana M, Cacchiarelli D, Legnini I, Santini T, Sthandier O, Chinappi M, Tramontano A, Bozzoni I. A long noncoding RNA controls muscle differentiation by functioning as a competing endogenous RNA. Cell. 2011;147(2):358–369. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.09.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang P, Xue Y, Han Y, Lin L, Wu C, Xu S, Jiang Z, Xu J, Liu Q, Cao X. The STAT3-binding long noncoding RNA lnc-DC controls human dendritic cell differentiation. Science. 2014;344(6181):310–313. doi: 10.1126/science.1251456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hosono Y, Niknafs YS, Prensner JR, Iyer MK, Dhanasekaran SM, Mehra R, Pitchiaya S, Tien J, Escara-Wilke J, Poliakov A, et al. Oncogenic role of THOR, a conserved cancer/testis long non-coding RNA. Cell. 2017;171(7):1559–1572 e1520. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.11.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hu X, Chen W, Li J, Huang S, Xu X, Zhang X, Xiang S, Liu C. ZFLNC: a comprehensive and well-annotated database for zebrafish lncRNA. Database. 2018 doi: 10.1093/database/bay114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pang Q, Ge J, Shao Y, Sun W, Song H, Xia T, Xiao B, Guo J. Increased expression of long intergenic non-coding RNA LINC00152 in gastric cancer and its clinical significance. Tumour Biol. 2014;35(6):5441–5447. doi: 10.1007/s13277-014-1709-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ji J, Tang J, Deng L, Xie Y, Jiang R, Li G, Sun B. LINC00152 promotes proliferation in hepatocellular carcinoma by targeting EpCAM via the mTOR signaling pathway. Oncotarget. 2015;6(40):42813–42824. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.5970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu Y, Tan C, Weng WW, Deng Y, Zhang QY, Yang XQ, Gan HL, Wang T, Zhang PP, Xu MD, et al. Long non-coding RNA Linc00152 is a positive prognostic factor for and demonstrates malignant biological behavior in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Am J Cancer Res. 2016;6(2):285–299. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cai Q, Wang ZQ, Wang SH, Li C, Zhu ZG, Quan ZW, Zhang WJ. Upregulation of long non-coding RNA LINC00152 by SP1 contributes to gallbladder cancer cell growth and tumor metastasis via PI3K/AKT pathway. Am J Transl Res. 2016;8(10):4068–4081. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen QN, Chen X, Chen ZY, Nie FQ, Wei CC, Ma HW, Wan L, Yan S, Ren SN, Wang ZX. Long intergenic non-coding RNA 00152 promotes lung adenocarcinoma proliferation via interacting with EZH2 and repressing IL24 expression. Mol Cancer. 2017;16(1):17. doi: 10.1186/s12943-017-0581-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhu Z, Dai J, Liao Y, Ma J, Zhou W. Knockdown of long noncoding RNA LINC00152 suppresses cellular proliferation and invasion in glioma cells by regulating miR-4775. Oncol Res. 2018;26(6):857–867. doi: 10.3727/096504017X15016337254597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Seo D, Kim D, Kim W. Long non-coding RNA linc00152 acting as a promising oncogene in cancer progression. Genomics inform. 2019;17(4):e36. doi: 10.5808/GI.2019.17.4.e36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhou J, Zhi X, Wang L, Wang W, Li Z, Tang J, Wang J, Zhang Q, Xu Z. Linc00152 promotes proliferation in gastric cancer through the EGFR-dependent pathway. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2015;34:135. doi: 10.1186/s13046-015-0250-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yu M, Xue Y, Zheng J, Liu X, Yu H, Liu L, Li Z, Liu Y. Linc00152 promotes malignant progression of glioma stem cells by regulating miR-103a-3p/FEZF1/CDC25A pathway. Mol Cancer. 2017;16(1):110. doi: 10.1186/s12943-017-0677-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 28.Chen P, Fang X, Xia B, Zhao Y, Li Q, Wu X. Long noncoding RNA LINC00152 promotes cell proliferation through competitively binding endogenous miR-125b with MCL-1 by regulating mitochondrial apoptosis pathways in ovarian cancer. Cancer Med. 2018;7(9):4530–4541. doi: 10.1002/cam4.1547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen ZP, Wei JC, Wang Q, Yang P, Li WL, He F, Chen HC, Hu H, Zhong JB, Cao J. Long noncoding RNA 00152 functions as a competing endogenous RNA to regulate NRP1 expression by sponging with miRNA206 in colorectal cancer. Int J Oncol. 2018;53(3):1227–1236. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2018.4451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shen X, Zhong J, Yu P, Zhao Q, Huang T. YY1-regulated LINC00152 promotes triple negative breast cancer progression by affecting on stability of PTEN protein. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2019;509(2):448–454. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.12.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang PP, Wang YQ, Weng WW, Nie W, Wu Y, Deng Y, Wei P, Xu MD, Wang CF. Linc00152 promotes cancer cell proliferation and invasion and predicts poor prognosis in lung adenocarcinoma. J Cancer. 2017;8(11):2042–2050. doi: 10.7150/jca.18852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lawson ND, Weinstein BM. In vivo imaging of embryonic vascular development using transgenic zebrafish. Dev Biol. 2002;248(2):307–318. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2002.0711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wertman J, Veinotte CJ, Dellaire G, Berman JN. The zebrafish xenograft platform: evolution of a novel cancer model and preclinical screening tool. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2016;916:289–314. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-30654-4_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu X, Wang P, Zhang C, Ma Z. Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR): a rising star in the era of precision medicine of lung cancer. Oncotarget. 2017;8(30):50209–50220. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.16854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schwartz PA, Kuzmic P, Solowiej J, Bergqvist S, Bolanos B, Almaden C, Nagata A, Ryan K, Feng J, Dalvie D, et al. Covalent EGFR inhibitor analysis reveals importance of reversible interactions to potency and mechanisms of drug resistance. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111(1):173–178. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1313733111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang Y, Xiang C, Wang Y, Duan Y, Liu C, Jin Y, Zhang Y. lncRNA LINC00152 knockdown had effects to suppress biological activity of lung cancer via EGFR/PI3K/AKT pathway. Biomed Pharmacother. 2017;94:644–651. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2017.07.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhao B, Xu H, Ai X, Adalat Y, Tong Y, Zhang J, Yang S. Expression profiles of long noncoding RNAs in lung adenocarcinoma. OncoTargets Ther. 2018;11:5383–5390. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S167633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Morton JJ, Bird G, Refaeli Y, Jimeno A. Humanized mouse xenograft models: narrowing the tumor-microenvironment gap. Cancer Res. 2016;76(21):6153–6158. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-1260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu TL, Upadhyayula S, Milkie DE, Singh V, Wang K, Swinburne IA, Mosaliganti KR, Collins ZM, Hiscock TW, Shea J, et al. Observing the cell in its native state: imaging subcellular dynamics in multicellular organisms. Science. 2018;360(6386):eaaq1392. doi: 10.1126/science.aaq1392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.