Abstract

Objectives

States vary significantly in their regulation of abortion. Misinformation about abortion is pervasive and propagated by state-mandated scripts that contain abortion myths. We sought to investigate women’s knowledge of abortion laws in their state. Our secondary objective was to describe women’s ability to discern myths about abortion from facts about abortion.

Study design

This was a cross-sectional study of English- and Spanish-speaking women aged 18–49 in the United States. We enrolled members of the GfK KnowledgePanel, a probability-based, nationally-representative online sample. Our primary outcome was the proportion of correct answers to 12 questions about laws regulating abortion in a respondent’s state. We asked five questions about common abortion myths. We used descriptive statistics to characterize performance on these measures and bivariate and multivariate modeling to identify risk factors for poor knowledge of state abortion laws.

Results

Of 2223 women contacted, 1057 (48%) completed the survey. The mean proportion of correct answers to 12 law questions was 18% (95% CI 17–20%). For three of five assessed myths, women endorsed myths about abortion over facts. Those who believe abortion should be illegal (aOR 2.18, CI 1.40–3.37), and those living in states with neutral or hostile state policies toward abortion (neutral aOR 1.99, CI 1.34–2.97; hostile aOR 1.6, CI 1.07–2.36) were at increased odds of poor law knowledge.

Conclusions

Women had low levels of knowledge about state abortion laws and commonly endorse abortion myths. Women’s knowledge of their state’s abortion laws was associated with personal views about abortion and their state policy environment.

Implications

Supporters of reproductive rights can use these results to show policy makers that their constituents are unlikely to know about laws being passed that may profoundly affect them. These findings underscore the potential benefit in correcting widely-held, medically-inaccurate beliefs about abortion so opinions about laws can be based on fact.

Keywords: Abortion, TRAP laws, Abortion myths, Access to abortion, Reproductive health, Reproductive rights

1. Introduction

Abortion is extremely safe and effective and high quality care is hindered rather than enhanced by state-level barriers [1]. Yet since 2011, states have enacted over 480 laws regulating abortion and restricting access to services including abortion bans in 12 states in 2019 [2], [3]. As of May 2020, 11 states had attempted to restrict abortion during the COVID-19 pandemic [4].

While no outright abortion ban is currently in effect in any state, abortion access is widely variable based on legislation in each state [5], [6]. Fifty-eight percent of reproductive-aged women live in states with policy hostile toward abortion [6]. Women who live in those states face hurdles such as 24–72 hour waiting periods prior to obtaining care, mandatory ultrasound viewing requirements, lack of access to telehealth for abortion, long distances to providers and stringent limits on gestational age [6], [7]. The interplay of frequent new legislation and legal challenges to those proposed restrictions may make it difficult for women to know whether they have access to abortion.

Additionally, some state laws propagate misinformation about abortion through state-mandated counseling scripts that contain abortion myths [8], [9]. Limited knowledge about targeted restriction of abortion providers (TRAP laws) and the fallacy that restrictions enhance abortion safety may bolster public support for TRAP laws [10]. Previous research has assessed reproductive health provider and clinic employee knowledge about state abortion laws [11], [12]. In contrast, research on US reproductive-aged women’s knowledge of specific state abortion laws is limited. A systematic review on women’s knowledge of abortion laws from 2016 identified no US studies [13]. Subsequent research in Texas showed low levels of knowledge of local abortion laws among reproductive-aged (aged 18–49) women [10]. Another study found poor knowledge of laws related to abortion among low-income immigrants (aged 15–45) in three cities across the United States [14]. Women who were first generation immigrants and from households that were primarily Spanish-speaking were less likely to correctly answer knowledge questions [14].

The aim of our study was to investigate women’s knowledge of laws regulating abortion in their state among a nationally-representative sample of reproductive-aged women. Our secondary objective was to describe women’s ability to discern myths about abortion from facts about abortion.

2. Materials and methods

We conducted a cross-sectional study, using a survey of a nationally-representative sample of women aged 18–49 who were members of GfK KnowledgePanel. This study received approval from the University of North Carolina Institutional Review Board (#18-2140).

2.1. Recruitment

GfK Knowledge Panel is a probability-based online panel that has been used for studies on health, including abortion and reproductive health [10], [15], [16]. GfK includes a statistically valid sampling method covering 97% of households in the United States. Prior to contacting respondents, GfK weights the pool of active members using geodemographic benchmarks from the most recent supplement of the U.S. Census Bureau’s Current Population Survey.

Women aged 18–49 who spoke English or Spanish were eligible to participate. Eligible women were invited to complete the survey by GfK originated email sent to them in their preferred language. Two pilot tests of the survey were done in January 2019 and February 2019. GfK administered the final survey to KnowledgePanel members for seven days in March 2019. Women who did not respond within three days were sent email reminders on days three and six after the original request for participation. The completion of each survey and each survey item were voluntary. Surveys that were incomplete were excluded from the final analysis. An incomplete survey was defined a-priori to be when greater than 50% of the questions were excluded or skipped.

2.2. Measures

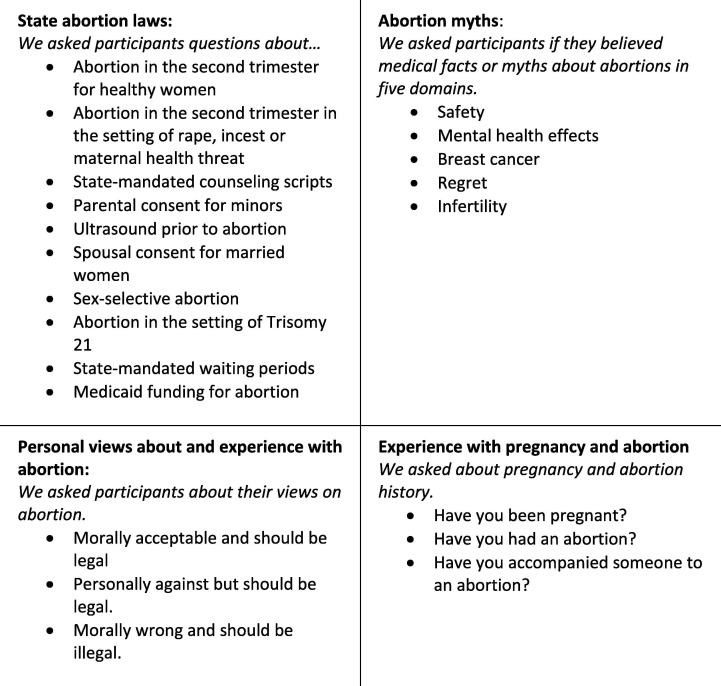

We designed a 41-item survey for our study (Fig. 1 and Appendix 1). We included items about abortion laws (12), about common abortion myths (5), personal views on abortion (1), self-reported pregnancy and abortion history (3), and health literacy (6) [21].

Fig. 1.

Knowledge of state abortion laws survey elements. A complete version of this survey is available in the Supplementary materials.

2.3. Abortion knowledge

The 12 items written to collect data about abortion law knowledge were adapted from survey questions used in prior studies [11], [12]. The items were designed to specifically ask how abortion laws might affect the general public. We did not include survey questions about laws that targeted abortion providers or facility requirements. Respondents were asked whether or not they thought particular laws were in place in their state. For instance, a respondent from Nebraska would be asked, “In Nebraska, is there a law that married women have to have their husband’s consent before an abortion?”. Possible answers included “yes,” “no”, and “not sure.” Respondents were encouraged to select “don’t know/not sure” instead of guessing. We asked one question about Medicaid funding of abortion and did not differentiate between use of state or federal funds. Funding of abortion through state Medicaid programs uses state rather than federal funds. We used Guttmacher Institute [17] and NARAL ProChoice America [18] to determine enacted state-specific abortion regulatory statutes. In the event of discrepancies between the two sources, we searched for state statutes based on data available in February 2019 (Appendix 2).

2.4. Abortion myths

The five items in the survey about common abortion myths have been used and reported in other published literature [8]. For each item we provided a statement of the common myth and a statement of the matching fact. We asked respondents to choose which of the two statements was closer to the truth. Respondents were encouraged to select “don’t know/not sure” instead of guessing.

2.5. Personal views on abortion and pregnancy history

We included one item to measure women’s personal views on abortion [10], [19]. We asked the question: “Which of the following statements about the issue of abortion comes closest to your own view?” Response options were: “I believe having an abortion is morally acceptable and should be legal;” “I am personally against abortion for myself, but I don’t believe government should prevent a woman from making that decision for herself;” “I believe having an abortion is morally wrong and should be illegal.”

We asked women whether they had been pregnant and among those with a pregnancy history, whether they ever had an abortion. We also asked whether they had accompanied someone else to obtain an abortion.

2.6. Health literacy

Health literacy is a measure of literacy, numeracy and comprehension that conveys an individual’s ability to understand information and make decisions related to their health. As they may have greater difficulty understanding medical information and more communication barriers [20], women with low health literacy may be especially susceptible to frequently changing legislation and state-supplied misinformation about abortion. We collected data on health literacy to determine if there would be an association between health literacy and knowledge of abortion laws. We used the Newest Vital Sign, a validated, rapid health literacy assessment available in English and Spanish [21]. We used this assessment to stratify respondents into three categories based on tool-specific guidance [21], “Low health literacy,” “Possible low health literacy,” and “Adequate health literacy.”

2.7. Demographics

Demographic characteristics of each GfK KnowledgePanel were provided for each survey respondent. These included age, education, race/ethnicity, number of people living in the household, marital status, rural or urban residence, state region, state of residence, employment status, political affiliation, religious affiliation and preferred language. We used data on number of family members living in the household and income to stratify respondents using the 2019 Federal Poverty Level (FPL). We coded households as <100%, 100–199% and greater than or equal to 200% of FPL. We condensed religious affiliation to six categories: no religion, Catholic, Christian (e.g. Protestant, Evangelical, Jehovah’s Witness, Mormon, Greek Orthodox, etc.), Jewish, Muslim, and other non-Christian (e.g. Hindu, Buddhist, etc.). We also condensed political affiliation to three categories from seven: Republican, Independent and Democrat.

At the conclusion of the survey, we offered evidence-based information on each of the included abortion myths and a link to a website where women could find a fact sheet of abortion laws in their state. We aimed to dispel myths encountered during the survey and answer questions that could have been raised through participation.

2.8. Analysis

Our primary outcome was the “knowledge sum score”. The lowest possible score was zero, when a respondent got none of the 12 knowledge questions correct. The highest possible score was a 12, when a respondent got all 12 questions. The score is the proportion of laws that respondents could correctly identify for their state. For each of the 12 knowledge questions, the answer was scored zero for an incorrect response or not sure, and one for a correct answer. All respondents had the same potential maximum score based on the laws in their state.

Our secondary outcome was a score based on women’s ability to correctly discern common myths about abortion from true statements. This score was a sum of true statements about abortion that respondents could identify. For example, respondents had to choose which of the following statements is closer to the truth: “Abortion is safer than childbirth,” or “Childbirth is safer than abortion.” In that example, the respondent would receive one point for the correct statement that “abortion is safer than childbirth” [22]. She would receive zero points for the myth statement “Childbirth is safer than abortion” or “Don’t know/Not sure.” We created a sum score for the five items. We performed a one-proportion Wald tests to test whether respondents were more likely to get answers correct or incorrect.

Our target sample size was 1000 women. This gave us a margin of error of 3.1% with a 95% confidence level around estimates. KnowledgePanel’s survey completion rate is about 60%, though lower in younger populations.

We prospectively planned bivariate and multivariate modeling with the sum score. However, in post-hoc analysis, we found the knowledge sum score total to be difficult to interpret as it is a new measure. Instead, we analyzed factors associated with a knowledge sum score of zero, representing no questions correct on the combined measure. For bivariate analyses, we performed adjusted Wald tests between categories. To investigate the association between each respondent characteristic and the likelihood of a score of zero, a multivariate logistic regression model was developed initially including all hypothesized associated characteristics and then sequentially eliminating non-significant characteristics with a Wald test. Characteristics with p = 0.1 or higher were maintained. All analyses were conducted in Stata 14 (College Station, Texas) with weights provided by GfK. Fig. 3, Fig. 4 were created in Tableau 2019.2.0 (Seattle, Washington). For this study, benchmark distributions of women 18 to 49 from the March 2018 Current Population Survey were used for adjustment of sample weights after data collection.

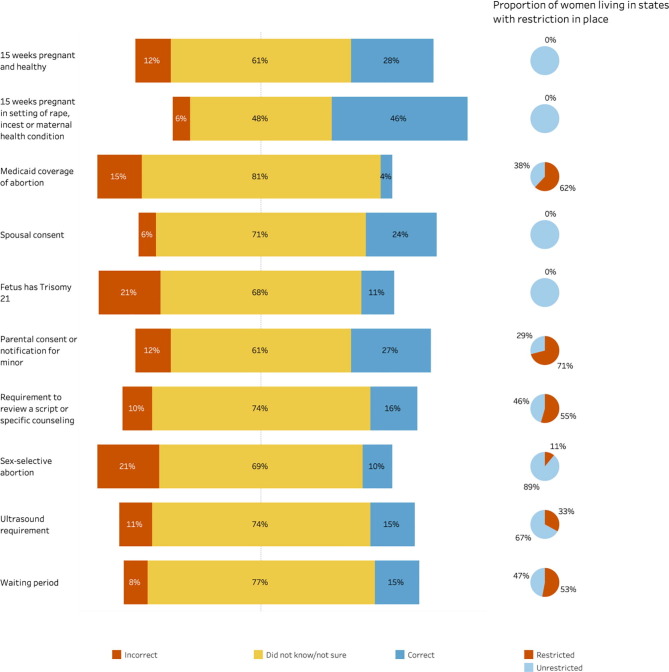

Fig. 3.

Women’s knowledge of state abortion restrictions and the proportion of women living in states with those restrictions in place. In the left column, women’s knowledge of abortion laws enacted in their state are depicted. On the right, the pie charts show the percentage of women in our sample who had the assessed law in place in their state. In one case (Trisomy 21), <1% of the sample did have the law in place, and it rounded to 0%. At the time of the survey (March 2019), recent legislative efforts to ban abortion before 15 weeks in some states had not been passed.

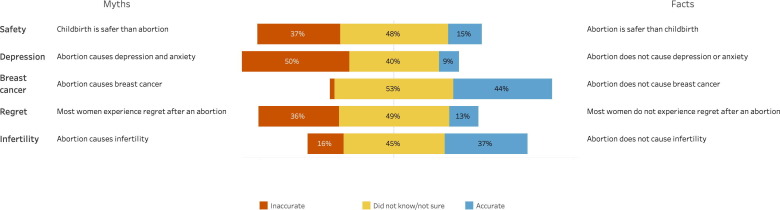

Fig. 4.

Women’s ability to discern myths about abortion from facts Women were asked which was more likely to be true between an accurate statement (shown on the right) and common abortion myth (shown on the left).

3. Results

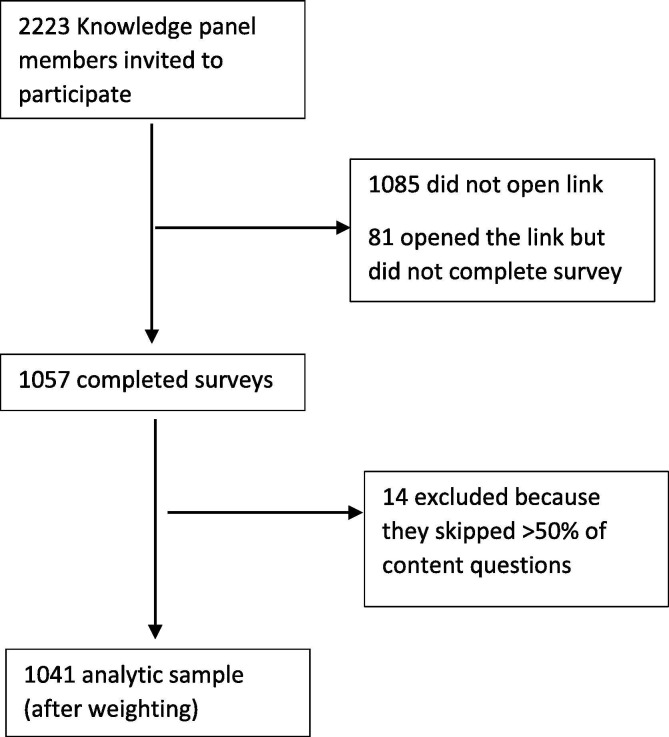

The survey was electronically sent to 2223 women; 1057 completed the survey and 14 were excluded for skipping more than 50% of questions for a response rate of 47%. After weighting, the analytic sample included 1041 women (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Respondent flowsheet. This depicts our recruitment and enrollment.

One thousand one hundred sixty-six women invited to participate declined. Those women were demographically similar with the exception of a larger proportion being low income and a larger proportion having lower levels of education. Only 81 panelists (4% of those invited) opened the survey and did not complete it.

Women from all states and the District of Columbia, except Hawaii, responded. Respondents were young (Table 1 ), well-educated and few came from households living below 100% of FPL. Women were diverse racially and ethnically. The majority had been pregnant in the past (617/1032; 59%), and a notably small minority reported a history of abortion (107/1032; 10%). The majority of respondents completed the survey in English.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and reproductive characteristics of women aged 18–49 participating in a U.S. survey on knowledge of abortion laws and myths in 2019, n = 1041.

| Score of 0 on knowledge of state abortion laws3 | Score of 1 or greater on knowledge of state abortion laws | |

|---|---|---|

| n = 379 (36%) | n = 662 (64%) | |

| Characteristic | n (%) | n (%) |

| Age | ||

| 18–29 | 139 (37) | 258 (39) |

| 30–39 | 121 (32) | 208 (31) |

| 40–49 | 120 (32) | 196 (30) |

| Education | ||

| Less than high school | 35 (9) | 59 (9) |

| High school graduate | 88 (23) | 152 (23) |

| Some college | 124 (33) | 206 (31) |

| Bachelor's degree or higher | 133 (35) | 245 (37) |

| Poverty status | ||

| <100% | 34 (9) | 63 (10) |

| 100–199% | 43 (11) | 66 (10) |

| ≥200 | 303 (80) | 532 (80) |

| Race | ||

| Non-Hispanic white, single race | 209 (55) | 373 (56) |

| Non-Hispanic black, single race | 51 (13) | 88 (13) |

| Non-Hispanic other or multiple race | 30 (8) | 59 (9) |

| Hispanic | 82 (22) | 130 (20) |

| 2+ Races, Non-Hispanic | 7 (2) | 12 (2) |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 196 (52) | 344 (52) |

| Divorced/widowed/Separated | 27 (7) | 55 (8) |

| Never married, living alone | 112 (29) | 197 (30) |

| Living with partner | 44 (12) | 66 (10) |

| Reproductive and abortion history | ||

| Has been pregnant | 207 (54) | 410 (62) |

| Has had an abortion | 27 (13) | 81 (20) |

| Has accompanied someone else to have an abortion | 19 (5) | 59 (9) |

| Survey language | ||

| English | 344 (91) | 628 (95) |

| Spanish | 36 (9) | 34 (5) |

| Residence region | ||

| Northeast | 60 (16) | 118 (18) |

| Midwest | 81 (21) | 130 (20) |

| South | 147 (39) | 252 (38) |

| West | 93 (24) | 161 (25) |

| Urban vs Rural | ||

| Urban | 54 (14) | 71 (11) |

| Rural | 326 (86) | 591 (89) |

| Personal views on abortion | ||

| Abortion is morally acceptable and should be legal | 95 (4) | 222 (33) |

| Personally against abortion, but government should not prevent a woman from making that decision | 165 (43) | 288 (44) |

| Abortion is morally wrong and should be illegal | 106 (28) | 141 (22) |

| Refused | 14 (4) | 11 (2) |

| Residence state and its associated abortion climate1 | ||

| Hostile toward abortion | 163 (43) | 266 (40) |

| Middle-Ground | 147 (39) | 220 (33) |

| Supportive | 70 (18) | 176 (27) |

| Religious affiliation | ||

| No religion | 113 (30) | 175 (26) |

| Catholic | 84 (22) | 152 (23) |

| Christian | 164 (44) | 277 (42) |

| Jewish | 8 (2) | 16 (2) |

| Muslim | 2 (1) | 9 (1) |

| Other non-Christian | 6 (2) | 31 (5) |

| Party affiliation | ||

| Republican | 134 (35) | 228 (34) |

| Undecided/Independent | 31 (8) | 29 (4) |

| Democrat | 215 (57) | 405 (61) |

| Health Literacy2 | ||

| Low health literacy | 27 (7) | 50 (8) |

| Potentially low health literacy | 53 (14) | 96 (15) |

| Adequate health literacy | 299 (79) | 515 (78) |

State abortion policy climate is based on grading by the Guttmacher institute. We condensed the Guttmacher five category grading system to three categories [6].

Health literacy was assessed using the Newest Vital Sign[22], a validated health literacy assessment.

Knowledge of state abortion laws was measured using a 12-item assessment querying whether individual abortion laws were enacted in the woman’s state of residence. Table 2 provides additional detail. Correct answers received one point. A score of zero means the respondent had no correct answers.

Most women believed that the government should not make abortion illegal (570/1041; 73%). (Table 1) The majority of the sample identified with the Democratic party. A plurality (428/1041; 41%) lived in states hostile toward abortion, whereas (367/1041; 35%) lived in middle ground states, and a minority (245/1041; 24%) lived in states supportive of abortion rights. A larger proportion of our sample were health literate than would have been anticipated in the general population [23].

3.1. Knowledge of state regulations

Women correctly answered 18% of questions (2/12 questions; 95% CI 17–19) about abortion regulations in their state, which was our primary outcome. We found the majority of women had limited knowledge of abortion laws. More than one third of respondents (380/1041, 36%; CI 33–40) did not answer any of the 12 questions correctly about abortion regulations in their state. Only two respondents (0.2%; CI 0–1) answered all 12 questions correctly. The most frequent answer for all the 12 questions about state abortion regulations was “Don’t know/Not sure” (range 41–83%). We focused on answers to each of the 12 knowledge questions (Fig. 3).

For context, we present the proportion of respondents who lived in a state with the regulations we assessed, as well as knowledge of those regulations (Fig. 3).

The question with the greatest number of correct answers (480/1041; 46%; CI 43–49) was about a theoretical gestational age limit of 15 weeks in the setting of rape, incest or threat to maternal health (Fig. 3 and Table 2 ). Although it was legal in every state, only 28% of respondents (288/1041; 28%; CI 25–31) were certain abortion at 15 weeks would be legal regardless of the indication. Likewise, only 24% (249/1040; CI 21–27) of women were aware that spousal consent was not required before an abortion. This is currently not an enacted statute in any state. Women also infrequently knew about laws regulating scripts or counseling prior to abortion, ultrasound requirements, legality of sex-selective abortion. state-mandated waiting periods or about Medicaid coverage of abortion.

Table 2.

Respondent knowledge of their state's abortion laws from a survey of knowledge about abortion in the U.S. in 2019.

| Question | n | Correct | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| If a woman were 15 weeks pregnant and healthy, would it be legal for her to get an abortion in [your state]? | 1039 | 28% | 25–31 |

| If a woman were 15 weeks pregnant and the pregnancy threatened her life, or was the result of rape, or was the result of incest, would it be legal for her to get an abortion in [your state]? | 1040 | 46% | 43–49 |

| In [your state], is there a law that requires a doctor to review a script or specific information with women prior to an abortion? | 1039 | 16% | 13–18 |

| In [your state], is there a law that requires minors to get parental consent and/or notify their parents before an abortion? | 1040 | 27% | 24–30 |

| In [your state], is there a law requiring women to have an ultrasound before an abortion? | 1039 | 15% | 13–17 |

| In [your state], is there a law that married women have to have their husband’s consent before an abortion? | 1040 | 24% | 21–27 |

| In [your state], is it legal to have an abortion based on whether the woman wants a boy or a girl? | 1039 | 10% | 8–12 |

| In [your state], is it legal to have an abortion because the fetus has Down syndrome? | 1038 | 11% | 19–24 |

| In [your state], is there a law that requires a woman seeking an abortion to wait a specified period of time between receiving counseling and when the procedure is performed?1 | 1038 | 15% | 13–17 |

| In [your state], does Medicaid cover abortion without restrictions?2 | 1034 | 4% | 3–6 |

Respondents who answered yes were then asked about the length of the waiting period (e.g. 24 h). Each question was worth one point. Those who correctly said their state had no waiting period received two points and did not see the second question.

Respondents who answered “yes, but only for some reasons” were then asked for what reasons Medicaid could cover abortion (e.g. for rape, incest or threat to the mother’s life). Each question was worth one point. Those who correctly said their state had Medicaid funding regardless of the indication received two points and did not see the second question.

3.2. Factors associated with knowledge of state abortion laws

A number of factors were associated with a score of zero on knowledge of state abortion laws. Spanish-speakers (OR 1.9, CI 1.10–3.26), women living in a state with policy neutral or hostile toward abortion as compared to supportive of abortion (neutral OR 1.67, CI 1.14–2.45, hostile OR 1.54, CI 1.06–2.23), and those believing abortion should be illegal (OR 1.74, CI 1.2–2.52) were at increased odds of having no knowledge of their state abortion laws. In contrast, a personal history of pregnancy (OR 0.73, CI 0.55–0.97) and personal experience with abortion (OR 0.52, CI 0.35–0.78) were associated with lower odds of a score of zero.

In multivariate logistic regression, Spanish-speaking women (aOR 2.21, CI 1.20–4.07), those with personal opposition to abortion who think it should be legal (aOR 1.48, CI 1.03–2.13), those who think abortion should be illegal (aOR 2.18, CI 1.40–3.37), and those living in states with neutral or hostile state policies toward abortion (neutral aOR 1.99, CI 1.34–2.97; hostile aOR 1.6, CI 1.07–2.36) were at increased odds of a zero knowledge score. (Table 3 ) A personal history of pregnancy (aOR 0.56, CI 0.41–0.78) was associated with decreased odds of a zero knowledge score.

Table 3.

Factors associated with a score of 0 on a knowledge assessment of state abortion laws from a U.S. survey in 2019.

|

Adjusted* OR |

||

|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | aOR | 95% CI |

| Age | ||

| 18–29 | Reference | |

| 30–39 | 1.31 | 0.92–1.88 |

| 40–49 | 1.49 | 1.02–2.18 |

| Survey Language | ||

| English | Reference | |

| Spanish | 2.21 | 1.20–4.07 |

| Religious affiliation | ||

| No religion | Reference | |

| Catholic | 0.6 | 0.39–0.91 |

| Christian | 0.65 | 0.45–0.95 |

| Jewish | 0.67 | 0.26–1.76 |

| Muslim | 0.32 | 0.04–2.33 |

| Other non-Christian | 0.32 | 0.10–0.96 |

| Pregnancy history | ||

| Never has been pregnant | Reference | |

| Has been pregnant | 0.56 | 0.41–0.78 |

| Personal views on abortion | ||

| Abortion is morally acceptable and should be legal | Reference | |

| Personally against abortion, but government should not prevent a woman from making that decision | 1.48 | 1.03–2.13 |

| Abortion is morally wrong and should be illegal | 2.18 | 1.40–3.37 |

| Residence state and its associated abortion climate1 | ||

| Supportive | Reference | |

| Middle-Ground | 1.99 | 1.34–2.97 |

| Hostile toward abortion | 1.6 | 1.07–2.36 |

To investigate the association between each respondent characteristic and the likelihood of a score of zero or answering no state abortion law knowledge questions correctly, a multivariate logistic regression model was developed. The model adjusts for age, survey language, personal views on abortion, state policy toward abortion, pregnancy history and religion.

State abortion policy climate is based on grading by the Guttmacher institute.

3.3. Abortion myths

Women correctly identified only 23% (CI 22–25%) of true statements about abortion. Almost half of respondents (468/1041; 45%; CI 42–48%) answered zero questions correctly when asked to differentiate myths from facts about abortion. For four of the five statements about abortion, the most frequent answer was “don’t know/not sure” (Fig. 4 and Table A1). On three of the five statements, respondents were more likely to endorse myths than true statements. Respondents incorrectly reported that abortion causes depression and anxiety (incorrect 50% CI 47–53%, correct 9% CI 7–11%, p < 0.001) [1], [24] and that most women who have had abortions experience regret (incorrect 36% CI 33–39%, correct 13% CI 11–16%, p < 0.001) [25]. Women were also likely to incorrectly believe that childbirth is safer than abortion (37% CI 34–40%, correct 15% CI 13–17%, p < 0.001) [22].

4. Discussion

In this nationally-representative assessment of reproductive-aged women’s knowledge of their state abortion laws, we found that few women had accurate impressions of the safety of abortion and related laws. Previous regional studies have presented similar findings [10], [14]. Surprisingly, we did not find poverty, low levels of education, or low health literacy to be associated with knowledge of state abortion laws. We also found that women were more likely than not to endorse abortion myths.

Our finding that women have low levels of knowledge about abortion laws is similar to other studies. We found consistently low knowledge across the US. Factors such as personal ideology about abortion and state of residence may shape knowledge about state abortion laws. Personal ideology has previously been noted to be associated with support for abortion laws [9], [19] and the belief that those restrictions enhance safety [19]. Respondents’ moral views on abortion were similar to prior studies [10], [19], [26]. We found personal and state of residence hostility toward abortion to be correlated with low knowledge of abortion laws. This observation suggests an additional barrier to abortion care—inaccurate knowledge of abortion laws—in environments hostile toward abortion.

We corroborated prior studies demonstrating frequent endorsement of abortion myths [8]. When considering women’s understanding about the safety of abortion and impact on health, inaccurate anti-abortion messaging and poor sexual health knowledge appears to outweigh abundant and compelling contrary evidence [1], [22], [24], [25], [27], [28], [29], [30], [31]. We found respondents to be highly misinformed on abortion safety, consistent with prior studies [8], [9], [10], [19]. While the risk of death from childbirth is 14 times that of death from abortion [22], respondents in our study were more likely to view childbirth as safer than abortion. Further, they were likely to believe abortion has adverse psychological consequences, which has been disproven in the short and long term [1], [24], [25], [31].

Some limitations should be considered. Only 10% of respondents reported a history of abortion, which is lower than contemporary lifetime incidence estimates in the US of just under 25% [32]. This may indicate either that this sample is not typical of the US population or social-desirability bias in responses. The response rate was somewhat lower than for other GfK studies. KnowledgePanel members are not informed about the content of the survey when they decide whether or not to follow the initial email link. Given the high participation rate among those who opened the survey, we suspect high social-desirability bias regarding self-reporting abortion. Few women in our study had low health literacy, which is expected from KnowledgePanel members who are regular survey respondents. Nationally, 36% of adults have basic or below basic health literacy [23]. Results may not be generalizable to less health literate populations.

Our findings should serve as a call to action to all clinicians to ensure their patients have accurate knowledge about their reproductive rights [2], [33], [34]. Knowledge about abortion laws is lowest in the areas most likely to introduce laws severely limiting abortion access. Reproductive rights advocates may need to provide significant educational context about new laws to rally opposition even though the majority of the public supports legal access to abortion [26].

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Lorin Bruckner for her help in developing figures to accompany this manuscript. We thank Tracy Truong, MS for her review of our statistical analysis.

Footnotes

Disclosure statement: The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Paper presentation information: An abstract of this work was accepted as for poster presentation at the North American Forum on Family Planning held in October 2019.

Funding: This work was supported by the Society of Family Planning Research Fund (SFPRF19-04).

Declaration of interests: The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.contraception.2020.08.001.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, Health and Medicine Division, Board on Health Care Services, Board on Population Health and Public Health Practice, Committee on Reproductive Health Services: Assessing the Safety and Quality of Abortion Care in the U.S. The Safety and Quality of Abortion Care in the United States. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2018. [PubMed]

- 2.Nash E. Abortion rights in peril — what clinicians need to know. N Engl J Med. 2019 doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1906972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.State Policy Trends 2019: A Wave of Abortion Bans, But Some States Are Fighting Back. Guttmacher Inst 2019. https://www.guttmacher.org/article/2019/12/state-policy-trends-2019-wave-abortion-bans-some-states-are-fighting-back (accessed February 12, 2020).

- 4.Jones R.K., Lindberg L., Witwer E. COVID-19 abortion bans and their implications for public health. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2020 doi: 10.1363/psrh.12139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Austin N., Harper S. Assessing the impact of TRAP laws on abortion and women’s health in the USA: a systematic review. BMJ Sex Reprod Health. 2018;44(2):128–134. doi: 10.1136/bmjsrh-2017-101866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nash E. State Abortion Policy Landscape: From Hostile to Supportive. Guttmacher Inst 2018. https://www.guttmacher.org/article/2019/08/state-abortion-policy-landscape-hostile-supportive (accessed June 8, 2020).

- 7.Cartwright A.F., Karunaratne M., Barr-Walker J., Johns N.E., Upadhyay U.D. Identifying national availability of abortion care and distance from major us cities: systematic online search. J Med Internet Res. 2018;20:e186. doi: 10.2196/jmir.9717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berglas N.F., Gould H., Turok D.K., Sanders J.N., Perrucci A.C., Roberts S.C.M. State-mandated (mis)information and women's endorsement of common abortion myths. Women's Health Issues. 2017;27:129–135. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2016.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bessett D., Gerdts C., Littman L.L., Kavanaugh M.L., Norris A. Does state-level context matter for individuals' knowledge about abortion, legality and health? Challenging the ‘red states v. blue states’ hypothesis. Cult Health Sex. 2015;17:733–746. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2014.994230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.White K., Potter J.E., Stevenson A.J., Fuentes L., Hopkins K., Grossman D. Women's knowledge of and support for abortion restrictions in Texas: findings from a statewide representative survey: knowledge and support for abortion restrictions in Texas. Perspect Sex Repro Health. 2016;48:189–197. doi: 10.1363/48e8716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dodge L.E., Haider S., Hacker M.R. Knowledge of state-level abortion laws and regulations among reproductive health care providers. Womens Health Issues Off Publ Jacobs Inst Womens Health. 2013;23:e281–e286. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2013.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dodge L.E., Haider S., Hacker M.R. Knowledge of state-level abortion laws and policies among front-line staff at facilities providing abortion services. Womens Health Issues Off Publ Jacobs Inst Womens Health. 2012;22:e415–e420. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2012.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Assifi A.R., Berger B., Tunçalp Ö., Khosla R., Ganatra B. Women’s awareness and knowledge of abortion laws: a systematic review. PLOS ONE. 2016;11:e0152224. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0152224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lara D., Holt K., Peña M., Grossman D. Knowledge of abortion laws and services among low-income women in three United States cities. J Immigr Minor Health. 2015;17:1811–1818. doi: 10.1007/s10903-014-0147-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grossman D., Hendrick E., Fuentes L., White K., Hopkins K., Stevenson A., Hubert Lopez C., Yeatman S., Potter J.E. Knowledge, opinion and experience related to abortion self-induction in Texas. Contraception. 2015;92:360–361. [Google Scholar]

- 16.KnowledgePanel. Ipsos n.d. https://www.ipsos.com/en-us/solutions/public-affairs/knowledgepanel (accessed February 12, 2020).

- 17.State Policies on Abortion. Guttmacher Inst n.d. https://www.guttmacher.org/united-states/abortion/state-policies-abortion (accessed February 12, 2020).

- 18.State Governments. NARAL-Choice Am n.d. https://www.prochoiceamerica.org/laws-policy/state-government/ (accessed April 11, 2017).

- 19.White K., Grossman D., Stevenson A.J., Hopkins K., Potter J.E. Does information about abortion safety affect Texas voters' opinions about restrictive laws? A randomized study. Contraception. 2017;96:381–387. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2017.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Committee Opinion No. 676: Health literacy to promote quality of care. Obstet Gynecol 2016;128:e183–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.The Newest Vital Sign|Pfizer: One of the world’s premier biopharmaceutical companies n.d. https://www.pfizer.com/health/literacy/public-policy-researchers/nvs-toolkit (accessed April 27, 2018).

- 22.Raymond E.G., Grimes D.A. The comparative safety of legal induced abortion and childbirth in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;119:215–219. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31823fe923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cutilli C.C., Bennett I.M. Understanding the health literacy of America: results of the National Assessment of Adult Literacy. Orthop Nurs Natl Assoc Orthop Nurses. 2009;28:27–32. doi: 10.1097/01.NOR.0000345852.22122.d6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Biggs M.A., Upadhyay U.D., McCulloch C.E., Foster D.G. Women’s mental health and well-being 5 years after receiving or being denied an abortion: a prospective, longitudinal cohort study. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74:169–178. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.3478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rocca C.H., Kimport K., Gould H., Foster D.G. Women's emotions one week after receiving or being denied an abortion in the United States. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2013;45:122–131. doi: 10.1363/4512213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Inc G. Abortion. GallupCom 2007. https://news.gallup.com/poll/1576/Abortion.aspx (accessed June 12, 2020).

- 27.Beral V., Bull D., Doll R., Peto R., Reeves G., Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer Breast cancer and abortion: collaborative reanalysis of data from 53 epidemiological studies, including 83?000 women with breast cancer from 16 countries. Lancet Lond Engl. 2004;363:1007–1016. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15835-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Committee on Gynecologic Practice. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 434: induced abortion and breast cancer risk. Obstet Gynecol 2009;113:1417–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Hogue C.J. Impact of abortion on subsequent fecundity. Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 1986;13:95–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vayssière C., Gaudineau A., Attali L., Bettahar K., Eyraud S., Faucher P. Elective abortion: clinical practice guidelines from the French College of Gynecologists and Obstetricians (CNGOF) Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2018;222:95–101. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2018.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Foster D.G., Steinberg J.R., Roberts S.C.M., Neuhaus J., Biggs M.A. A comparison of depression and anxiety symptom trajectories between women who had an abortion and women denied one. Psychol Med. 2015;45:2073–2082. doi: 10.1017/S0033291714003213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jones R.K., Jerman J. Population group abortion rates and lifetime incidence of abortion: United States, 2008–2014. Am J Public Health. 2017;107:1904–1909. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2017.304042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Espey E., Dennis A., Landy U. The importance of access to comprehensive reproductive health care, including abortion: a statement from women’s health professional organizations. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;220:67–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2018.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.A statement on abortion by 100 professors of obstetrics: 40 years later. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2013;209:193–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.