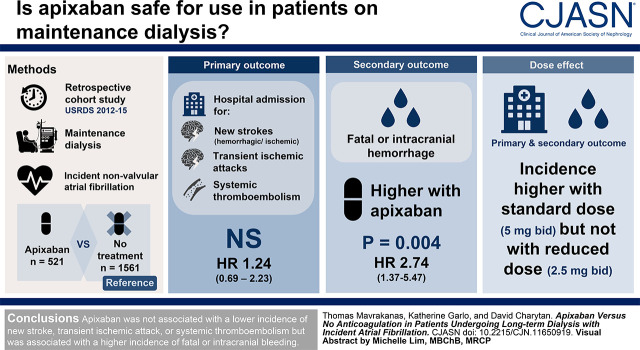

Visual Abstract

Keywords: apixaban, atrial fibrillation, dialysis, mortality, ischemic stroke, hemorrhagic stroke, Ischemic Attack, Transient, Stroke, Propensity Score, Incidence, Retrospective Studies, Brain Ischemia, Pyridones, Pyrazoles, Anticoagulants, Thromboembolism, Myocardial Infarction

Abstract

Background and objectives

The relative efficacy and safety of apixaban compared with no anticoagulation have not been studied in patients on maintenance dialysis with atrial fibrillation. We aimed to determine whether apixaban is associated with better clinical outcomes compared with no anticoagulation in this population.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

This retrospective cohort study used 2012–2015 US Renal Data System data. Patients on maintenance dialysis with incident, nonvalvular atrial fibrillation treated with apixaban (521 patients) were matched for relevant baseline characteristics with patients not treated with any anticoagulant agent (1561 patients) using a propensity score. The primary outcome was hospital admission for a new stroke (ischemic or hemorrhagic), transient ischemic attack, or systemic thromboembolism. The secondary outcome was fatal or intracranial bleeding. Competing risk survival models were used.

Results

Compared with no anticoagulation, apixaban was not associated with lower incidence of the primary outcome: hazard ratio, 1.24; 95% confidence interval, 0.69 to 2.23; P=0.47. A significantly higher incidence of fatal or intracranial bleeding was observed with apixaban compared with no treatment: hazard ratio, 2.74; 95% confidence interval, 1.37 to 5.47; P=0.004. A trend toward fewer ischemic but more hemorrhagic strokes was seen with apixaban compared with no treatment. No significant difference in the composite outcome of myocardial infarction or ischemic stroke was seen with apixaban compared with no treatment. Compared with no anticoagulation, a significantly higher rate of the primary outcome and a significantly higher incidence of fatal or intracranial bleeding and of hemorrhagic stroke were seen in the subgroup of patients treated with the standard apixaban dose (5 mg twice daily) but not in patients who received the reduced apixaban dose (2.5 mg twice daily).

Conclusions

In patients with kidney failure and nonvalvular atrial fibrillation, treatment with apixaban was not associated with a lower incidence of new stroke, transient ischemic attack, or systemic thromboembolism but was associated with a higher incidence of fatal or intracranial bleeding.

Podcast

This article contains a podcast at https://www.asn-online.org/media/podcast/CJASN/2020_05_29_CJN11650919.mp3

Introduction

Patients with kidney failure on hemodialysis have a very high prevalence of atrial fibrillation (up to 40%) (1). However, despite the high prevalence of atrial fibrillation, it is unclear whether these patients should be anticoagulated. Currently, no randomized data exist regarding use of either vitamin K antagonists or direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) in this population. Conversely, several well conducted cohort studies have analyzed the safety and efficacy of warfarin. These studies had conflicting results, but most failed to show a benefit from warfarin administration compared with no treatment with respect to stroke prevention, whereas warfarin use was associated with significantly higher risk of bleeding (2).

Off-label use of dabigatran or rivaroxaban in patients on hemodialysis with atrial fibrillation was associated with even more major bleeding events and higher risk of death from bleeding when compared with warfarin in one study (3). In addition, it was unclear whether use of either agent reduced the risk of stroke.

Apixaban has lower elimination by the kidneys compared with other DOACs (25%–29%). It is the most commonly used drug among DOAC-treated patients with kidney failure in the United States (4). However, appropriate dose adjustment may be an issue because the drug accumulates with prolonged use, with the standard dose leading to supratherapeutic drug levels in some patients on hemodialysis and the reduced dose leading to drug levels at the lower range of the therapeutic interval (5). A recently published retrospective cohort study, using the US Renal Data System, showed that apixaban-treated patients had similar event rates for ischemic stroke or systemic thromboembolism compared with warfarin-treated patients but benefited from significantly lower major bleeding event rates (6). Furthermore, apixaban at the standard dose of 5 mg twice daily was associated with significantly lower risk for ischemic stroke or systemic thromboembolism compared with warfarin, in contrast to what was observed with the reduced dose of 2.5 mg twice daily.

These data are reassuring regarding the potential benefits of apixaban compared with warfarin. However, given the relative inefficacy of warfarin in preventing stroke or systemic thromboembolism in patients with kidney failure and the high bleeding event rates associated with anticoagulation in this patient group, it is critical to assess the relative efficacy and safety of apixaban compared with no anticoagulation before advocating for its use in patients receiving maintenance dialysis. To address this question, we aimed to determine whether apixaban is associated with better clinical outcomes compared with no anticoagulation in patients on maintenance dialysis with atrial fibrillation.

Materials and Methods

Study Population

This retrospective cohort study used US Renal Data System data from 2012 to 2015 (7). We identified all patients on hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis on January 1, 2012 (prevalent population) or who were started on hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis between January 1, 2012 and December 31, 2015 (incident population).

We next identified all individuals with a primary or secondary diagnosis of atrial fibrillation or flutter on the basis of at least one inpatient or two outpatient claims using condition-specific diagnostic codes (International Classification of Diseases, ninth and tenth revisions). To verify whether this was a new diagnosis or a preexisting comorbidity, the claims dataset (ESKD and pre-ESKD) was reviewed for the year preceding the date of entry in the cohort. We restricted our analysis to patients who (1) had a new diagnosis of atrial fibrillation after January 1, 2012; (2) were alive on day 30 postdiagnosis, in order to exclude patients who developed atrial fibrillation in the setting of a serious intercurrent illness; (3) had continuous Medicare Part A and B coverage for the year prior to diagnosis; (4) had part D enrollment for ≥6 months prior to diagnosis; (5) did not have valvular atrial fibrillation; and (6) did not have a prescription of any anticoagulant agent in the 6 months prior to diagnosis (8). Atrial fibrillation was considered to be valvular if the patient had a prosthetic valve or mitral stenosis.

Relevant baseline characteristics and medication prescription (new and prevalent) were retrieved for each patient from institutional and physician claims (the 2728 form was not used). The congestive heart failure, hypertension, age, diabetes, stroke, vascular history (CHA2DS2-Vasc) score and a modified hypertension, kidney disease, liver disease, stroke, prior bleeding or predisposition to bleeding, labile international normalized ratios, age, medication, alcohol use (HAS-BLED) score were calculated. The modified HAS-BLED score used all variables of the original score except labile international normalized ratios (9,10).

We compared patients treated with apixaban with patients who did not receive any anticoagulation.

Restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for this study and, therefore, are not publicly available. The Partners Healthcare institutional review board approved the study (2016P001613/BWH) and ruled that informed consent was not necessary. This work was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was hospital admission for a new stroke (ischemic or hemorrhagic), transient ischemic attack, or systemic thromboembolism. The secondary outcomes were any stroke (ischemic or hemorrhagic), fatal or intracranial bleeding, clinically important bleeding, ischemic stroke, hemorrhagic stroke, a composite outcome of myocardial infarction or ischemic stroke, a composite outcome of all-cause mortality and the primary outcome, and all-cause mortality. We additionally examined two outcomes not expected to be related to use of apixaban to assess the specificity of our findings: pneumonia and hip fracture. The institutional inpatient claims dataset was used, and one condition-specific diagnostic code was requested for each outcome (Supplemental Table 1).

Clinically important bleeding was defined as any bleeding resulting in death; any bleeding occurring at a critical site (intracranial, intraocular, retroperitoneal, intra-articular, pericardial, airway); or any gastrointestinal, urinary tract, or gynecologic bleeding requiring hospitalization.

The follow-up period (time 0) started 30 days after atrial fibrillation diagnosis to allow enough time for patients to fill a prescription and to exclude patients who developed atrial fibrillation in the setting of a serious intercurrent illness. Patients were followed up to the date of death, kidney transplantation, or December 31, 2015. For the outcome of all-cause mortality, patients were followed up to the date of death, kidney transplantation, or August 1, 2017 because data for mortality were available until this date. Time to event data for each outcome in the apixaban and the control group are shown in Supplemental Table 2.

Statistical Analyses

Multivariable logistic regression was used to calculate a propensity score for apixaban prescription versus no anticoagulation including 23 parameters at baseline selected for their potential association with cardiovascular or bleeding outcomes (shown in Table 1). Apixaban users were matched 1:3 without replacement according to the propensity score (caliper width of 0.5%) to patients not treated with any anticoagulant agent. Standardized differences were calculated to assess balance of the matched cohorts, with a cutoff of ≤0.1 considered to indicate a negligible difference (11).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the unmatched and matched cohort

| Characteristics | Unmatched Cohort | Matched Cohort | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Treatment | Apixaban | Standardized Difference | No Treatment | Apixaban | Standardized Difference | |

| No. of patients | 10,976 | 521 | 1561 | 521 | ||

| Demographics | ||||||

| Age | 67±13 | 68±11 | −0.03 | 68±13 | 68±11 | 0.04 |

| Men | 5920 (54%) | 281 (54%) | 0.00 | 824 (53%) | 281 (54%) | 0.02 |

| Black race | 3378 (31%) | 116 (22%) | −0.19 | 333 (21%) | 116 (22%) | 0.02 |

| Hemodialysis | 9831 (90%) | 453 (87%) | −0.08 | 1374 (88%) | 453 (87%) | −0.03 |

| Dialysis vintage, mo | 26 (10–57) | 19 (6–33) | 0.33 | 19 (6–38) | 19 (6–33) | 0.01 |

| Comorbidities | ||||||

| Hypertension | 10,916 (100%) | 520 (100%) | 0.05 | 1557 (100%) | 520 (100%) | 0.02 |

| Diabetes | 8778 (80%) | 419 (80%) | 0.01 | 1251 (80%) | 419 (80%) | 0.01 |

| Coronary disease | 8302 (76%) | 387 (74%) | −0.03 | 1150 (74%) | 387 (74%) | 0.01 |

| Heart failure | 8243 (75%) | 397 (76%) | 0.03 | 1187 (76%) | 397 (76%) | 0.00 |

| Myocardial infarction | 2953 (27%) | 110 (21%) | −0.14 | 349 (22%) | 110 (21%) | −0.03 |

| Stroke history | 4375 (40%) | 178 (34%) | −0.12 | 564 (36%) | 178 (34%) | −0.04 |

| PVD | 6571 (60%) | 285 (55%) | −0.11 | 854 (55%) | 285 (55%) | 0.00 |

| Dyslipidemia | 9333 (85%) | 472 (91%) | 0.17 | 1420 (91%) | 472 (91%) | −0.01 |

| Malignancy | 3163 (29%) | 149 (29%) | 0.00 | 457 (29%) | 149 (29%) | −0.02 |

| Alcohol-related disease | 1603 (15%) | 59 (11%) | −0.10 | 175 (11%) | 59 (11%) | 0.00 |

| Liver disease | 3550 (32%) | 134 (26%) | −0.15 | 371 (24%) | 134 (26%) | 0.04 |

| COPD | 4755 (43%) | 207 (40%) | −0.07 | 606 (39%) | 207 (40%) | 0.02 |

| Bleeding history | 6346 (58%) | 254 (49%) | −0.18 | 752 (48%) | 254 (49%) | 0.01 |

| Medication | ||||||

| ACEI | 3301 (30%) | 134 (26%) | −0.10 | 384 (25%) | 134 (26%) | 0.03 |

| ARB | 2030 (19%) | 97 (19%) | 0.00 | 293 (19%) | 97 (19%) | −0.01 |

| Antiplatelet agent | 2688 (25%) | 117 (23%) | −0.05 | 356 (23%) | 117 (23%) | −0.01 |

| β-Blocker | 7564 (69%) | 379 (73%) | 0.08 | 1126 (72%) | 379 (73%) | 0.01 |

| Statin | 5806 (53%) | 313 (60%) | 0.15 | 942 (60%) | 313 (60%) | 0.00 |

Results are presented as mean ± SD, median (interquartile range), or number (percentage). PVD, peripheral vascular disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker.

Cox proportional hazard models were used to examine the association between apixaban prescription and the clinical outcomes, considering death from any cause as a competing risk, as described by Fine and Gray (12). For the main “as-treated” analysis, we censored patients when Medicare Part A, B, or D coverage was lost. We also censored apixaban users at the date of the last available prescription plus drug supply days. To account for immortal time bias for patients prescribed apixaban at >30 days from atrial fibrillation diagnosis, we examined apixaban prescription as a time-varying covariate (13). For the primary analysis, hazard ratios (HRs) were not adjusted. For the secondary analysis, HRs were adjusted for (1) CHA2DS2-Vasc score for the primary outcome, ischemic stroke, any stroke, and all-cause mortality; (2) modified HAS-BLED score for fatal or intracranial bleeding, hemorrhagic stroke, and clinically important bleeding; and (3) history of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, and myocardial infarction for the composite outcome of myocardial infarction or ischemic stroke.

We performed a subgroup analysis including only patients with apixaban either 5 mg twice daily or 2.5 mg twice daily to study the effect of the standard dose and the reduced dose on relevant clinical outcomes. We also separately present outcomes for the subgroup of patients on maintenance hemodialysis.

We performed three sensitivity analyses: (1) an “intention-to-treat” analysis, where we assumed that each patient remained on apixaban throughout the whole follow-up period (14); (2) a prescription time-distribution matching to account for immortal time bias: the time to apixaban prescription was assessed for users (for each nonuser, an assigned “time to apixaban” was randomly selected from this distribution of observed times to apixaban start; the two groups were followed from the date of apixaban prescription [real or assigned] until the occurrence of an event or the end of follow-up, and nonusers with an event prior to assigned time 0 were excluded from this analysis [13]); and (3) a marginal structural model where stabilized inverse probability weights were estimated and then used in Cox proportional hazards regression. The primary analysis was also performed in a larger dataset to further include patients with prevalent atrial fibrillation at the time of dialysis initiation.

Statistical analyses were performed in SPSS Statistics (version 24.0, Released 2016; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY) or in Stata (version 14 IC; College Station, TX). P values =0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Cohort and Patient Characteristics

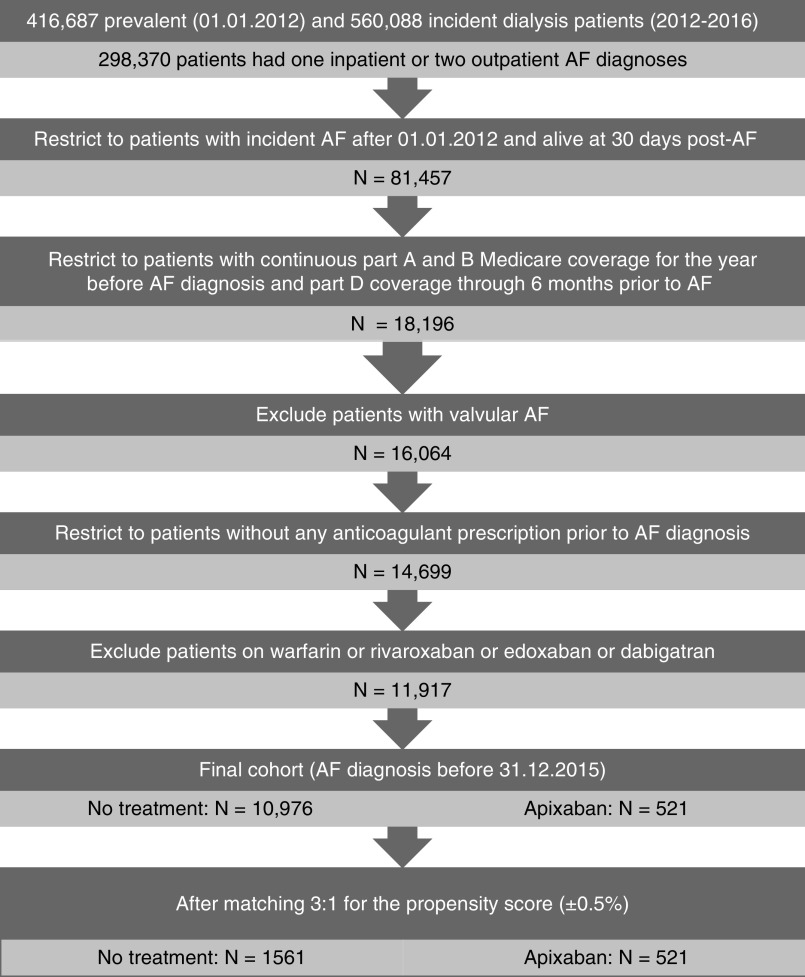

Population selection is detailed in Figure 1. The final cohort included 10,976 patients who did not receive any anticoagulant agent and 521 patients on apixaban. After propensity-score matching, the cohort included 2082 patients (521 on apixaban and 1561 without any anticoagulant prescription). Baseline characteristics of the final and matched cohorts that could be considered as potential confounders are shown in Supplemental Table 3 and Table 1 for the subgroup of patients on maintenance hemodialysis and the whole cohort, respectively. The matched cohort was well matched for all baseline characteristics.

Figure 1.

Study flowchart: population selection from the US Renal Data System. AF, atrial fibrillation.

The median time between atrial fibrillation diagnosis and apixaban initiation was 24 days (interquartile range, 0–200 days). The mean duration of apixaban use was 155±150 days (median, 96 days; interquartile range, 30–225 days). A total of 207 patients received the standard dose (5 mg twice daily), and 257 patients received the reduced dose (2.5 mg twice daily), whereas 57 patients switched doses.

Primary Outcome

Compared with no anticoagulant therapy, apixaban use was not associated with lower risk of a new stroke (ischemic or hemorrhagic), transient ischemic attack, or systemic thromboembolism: 7.5 events per 100 patient-years in apixaban-treated patients versus 7.0 events in patients who did not receive any anticoagulant (HR, 1.24; 95% confidence interval [95% CI], 0.69 to 2.23; P=0.47) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Clinical outcomes in the “as-treated” population (main analysis)

| Outcome | Incidence in Apixaban Users | Incidence in Nonusers | Crude Hazard Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) | P Value | Adjusteda Hazard Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any stroke, TIA, or embolism | 7.5 (13) | 7.0 (114) | 1.24 (0.69 to 2.23) | 0.47 | 1.29 (0.72 to 2.33) | 0.39 |

| Any stroke | 5.8 (<11) | 5.8 (96) | 1.13 (0.58 to 2.19) | 0.72 | 1.17 (0.60 to 2.28) | 0.64 |

| Major bleeding | 4.9 (<11) | 1.6 (45) | 2.74 (1.37 to 5.47) | 0.004 | 2.76 (1.38 to 5.52) | 0.004 |

| Clinically important bleeding | 59.2 (77) | 56.9 (695) | 1.15 (0.90 to 1.47) | 0.26 | 1.15 (0.90 to 1.46) | 0.26 |

| Ischemic stroke or MI | 27.6 (43) | 25.1 (373) | 1.24 (0.90 to 1.71) | 0.18 | 1.25 (0.91 to 1.72) | 0.17 |

| Ischemic stroke | 3.5 (<11) | 5.0 (81) | 0.81 (0.35 to 1.89) | 0.63 | 0.85 (0.36 to 1.98) | 0.71 |

| Hemorrhagic stroke | 2.3 (<11) | 1.3 (22) | 1.89 (0.65 to 5.47) | 0.24 | 1.89 (0.65 to 5.49) | 0.24 |

Incidence rates are presented as number of events per 100 patient-years, with the number of events per group shown in parentheses. Patients were followed up to the date of death; kidney transplantation; December 31, 2015; loss of Medicare A–B or D coverage; or the date of the last available apixaban prescription (plus drug supply days). Death was considered as a competing risk. TIA, transient ischemic attack; MI, myocardial infarction.

Hazard ratios were adjusted for the CHA2DS2-Vasc (congestive heart failure, hypertension, age, diabetes, stroke, vascular history) score for the outcomes of any stroke; any stroke, TIA, or systemic thromboembolism; and ischemic stroke; for a modified HAS-BLED (hypertension, kidney disease, liver disease, stroke, prior bleeding or predisposition to bleeding, labile international normalized ratio, age, medication, alcohol use) score for major bleeding, hemorrhagic stroke, and clinically important bleeding; and for history of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, and MI for the outcome of ischemic stroke or MI. Statistically significant differences appear in bold.

Although a tendency that did not reach statistical significance toward fewer ischemic strokes was identified with apixaban compared with no treatment, it was offset by a tendency toward more hemorrhagic strokes in apixaban-treated patients (Table 2).

Secondary Outcomes

Apixaban use was associated with a significantly higher incidence of fatal or intracranial bleeding events compared with no treatment: 4.9 versus 1.6 events per 100 patient-years (HR, 2.74; 95% CI, 1.37 to 5.47; P=0.004) (Table 2). This finding translates into one fatal or intracranial bleeding event per 30 patients treated with apixaban per year.

A similar incidence of clinically important bleeding events was observed with apixaban compared with no treatment (Table 2). No significant difference in the composite outcome of myocardial infarction or ischemic stroke and the composite outcome of any stroke was seen with apixaban compared with no treatment (Table 2).

Mortality and Composite Outcome

Apixaban use was associated with lower all-cause mortality rates compared with no anticoagulation (HR, 0.58; 95% CI, 0.43 to 0.78). Similarly, apixaban use was associated with lower incidence of the composite outcome of all-cause mortality or stroke or systemic thromboembolism compared with no treatment (HR, 0.56; 95% CI, 0.41 to 0.76).

To evaluate the hypothesis of healthy user bias, we evaluated two more outcomes that should not be influenced by apixaban use: hospital admission for pneumonia or hip fracture. For both outcomes, a lower incidence was seen in apixaban users: HR, 0.77 for pneumonia (95% CI, 0.55 to 1.07) and HR, 0.19 for hip fracture (95% CI, 0.03 to 1.36).

Standard-Dose and Reduced-Dose Apixaban Compared with No Treatment

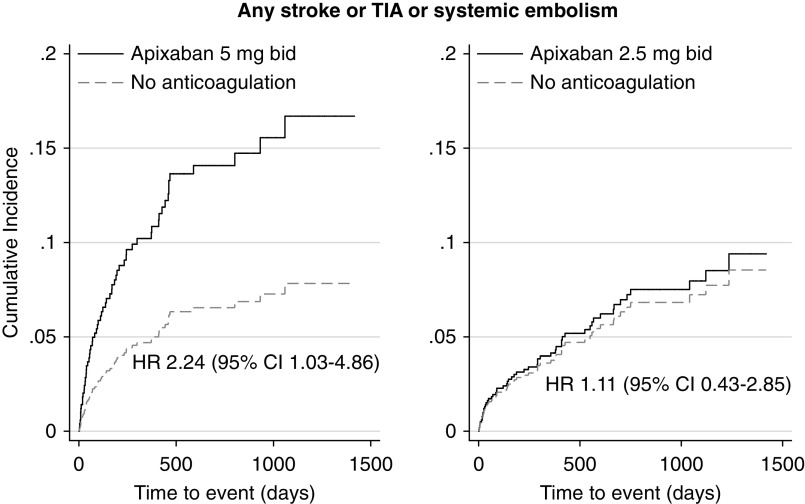

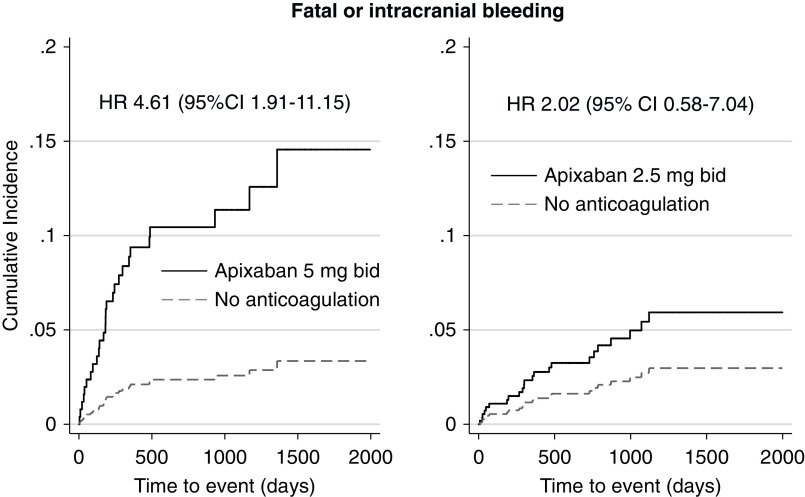

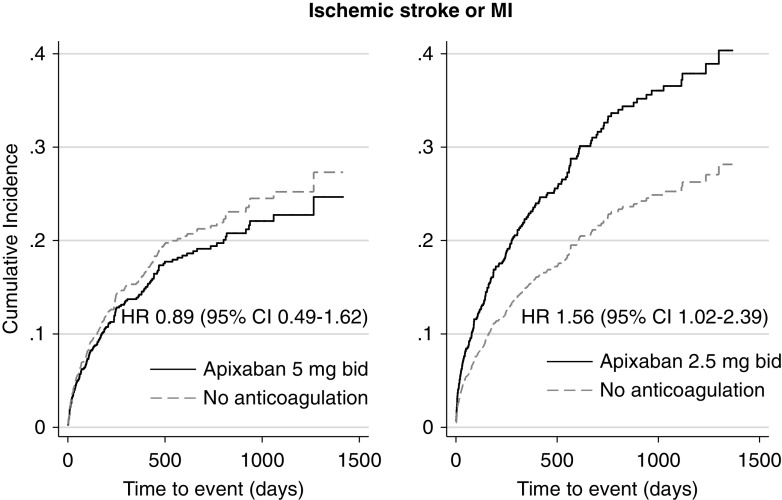

Compared with no anticoagulation, a significantly higher rate of the primary outcome and significantly higher incidence of fatal or intracranial bleeding and of hemorrhagic stroke were seen in the subgroup of patients treated with the standard apixaban dose (n=207 patients) but not in patients who received the reduced apixaban dose (n=257 patients) (Figures 2 and 3, Table 3). On the contrary, a higher rate of the composite outcome of myocardial infarction or ischemic stroke was observed in the subgroup of patients who received the reduced apixaban dose compared with no treatment (Figure 4, Table 3).

Figure 2.

A significantly higher incidence of any stroke, transient ischemic attack (TIA), or systemic thromboembolism was seen in the subgroup of patients treated with the standard apixaban dose but not in patients who received the reduced apixaban dose, compared with patients who did not receive any anticoagulants. Adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) are depicted. Death was considered as competing risk. Apixaban prescription was examined as a time-varying covariate. bid, twice daily; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

Figure 3.

A significantly higher incidence of fatal or intracranial (major) bleeding was seen in the subgroup of patients treated with the standard apixaban dose but not in patients who received the reduced apixaban dose, compared with patients who did not receive any anticoagulants. Adjusted HRs are depicted. Death was considered as competing risk. Apixaban prescription was examined as a time-varying covariate.

Table 3.

Clinical outcomes in patients treated with apixaban at the standard or reduced dose compared with patients who received no treatment

| Outcome | Incidence in Apixaban Users | Incidence in Nonusers | Crude Hazard Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) | P Value | Adjusteda Hazard Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard-dose apixaban (5 mg twice daily) versus no treatment | ||||||

| Any stroke, TIA, or embolism | 13.6 (<11) | 7.6 (51) | 1.80 (0.84 to 3.86) | 0.13 | 2.24 (1.03 to 4.86) | 0.04 |

| Any stroke | 10.3 (<11) | 6.4 (43) | 1.61 (0.66 to 3.90) | 0.29 | 1.94 (0.79 to 4.75) | 0.15 |

| Major bleeding | 9.8 (<11) | 1.7 (20) | 4.33 (1.81 to 10.35) | 0.001 | 4.61 (1.91 to 11.15) | 0.001 |

| Clinically important bleeding | 77.2 (34) | 57.2 (291) | 1.31 (0.91 to 1.89) | 0.15 | 1.36 (0.94 to 1.96) | 0.10 |

| Ischemic stroke or MI | 22.0 (12) | 24.2 (151) | 0.91 (0.50 to 1.66) | 0.76 | 0.89 (0.49 to 1.62) | 0.70 |

| Ischemic stroke | 3.4 (<11) | 4.8 (32) | 0.72 (0.16 to 3.17) | 0.66 | 0.90 (0.20 to 4.01) | 0.89 |

| Hemorrhagic stroke | 6.8 (<11) | 2.1 (14) | 3.31 (1.07 to 10.22) | 0.04 | 3.43 (1.10 to 10.77) | 0.03 |

| Reduced-dose apixaban (2.5 mg twice daily) versus no treatment | ||||||

| Any stroke, TIA, or embolism | 5.7 (<11) | 6.1 (50) | 1.15 (0.45 to 2.93) | 0.77 | 1.11 (0.43 to 2.85) | 0.84 |

| Any stroke | 4.5 (<11) | 5.2 (43) | 1.04 (0.37 to 2.93) | 0.94 | 0.99 (0.35 to 2.81) | 0.99 |

| Major bleeding | 2.9 (<11) | 1.4 (20) | 2.03 (0.59 to 7.04) | 0.26 | 2.02 (0.58 to 7.04) | 0.27 |

| Clinically important bleeding | 51.4 (33) | 54.7 (338) | 1.06 (0.74 to 1.52) | 0.75 | 1.03 (0.71 to 1.47) | 0.89 |

| Ischemic stroke or MI | 31.8 (25) | 24.2 (180) | 1.53 (1.00 to 2.34) | 0.05 | 1.56 (1.02 to 2.39) | 0.04 |

| Ischemic stroke | 4.5 (<11) | 4.7 (39) | 1.17 (0.41 to 3.29) | 0.77 | 1.11 (0.39 to 3.17) | 0.84 |

| Hemorrhagic stroke | No events | 0.5 (<11) | — | — |

Incidence rates are presented as number of events per 100 patient-years, with the number of events per group shown in parentheses. Patients were followed up to the date of death; kidney transplantation; December 31, 2015; loss of Medicare A–B or D coverage; or the date of the last available apixaban prescription (plus drug supply days). Death was considered as a competing risk. TIA, transient ischemic attack; MI, myocardial infarction.

Hazard ratios were adjusted for the CHA2DS2-Vasc (congestive heart failure, hypertension, age, diabetes, stroke, vascular history) score for the outcomes of any stroke; any stroke, TIA, or systemic thromboembolism; and ischemic stroke; for a modified HAS-BLED (hypertension, kidney disease, liver disease, stroke, prior bleeding or predisposition to bleeding, labile international normalized ratios, age, medication, alcohol use) score for major bleeding, hemorrhagic stroke, and clinically important bleeding; and for history of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, and MI for the outcome of ischemic stroke or MI. Statistically significant differences appear in bold.

Figure 4.

A significantly higher incidence of ischemic stroke or MI was seen in the subgroup of patients treated with the reduced apixaban dose but not in patients who received the standard apixaban dose, compared with patients who did not receive any anticoagulants. Adjusted HRs are depicted. Death was considered as competing risk. Apixaban prescription was examined as a time-varying covariate.

Subgroup and Sensitivity Analyses

Results for patients on maintenance hemodialysis are shown in Supplemental Table 4 and were qualitatively consistent with the main analysis. The number of patients on peritoneal dialysis who received apixaban was very small, and no strokes were observed in this subgroup. Therefore, no meaningful conclusions can be drawn for patients on peritoneal dialysis. The “intention-to-treat” analysis, the time-distribution matched analysis, and the marginal structural model analysis yielded qualitatively similar results compared with the main analysis with respect to the primary and secondary outcomes (Supplemental Table 5).

When patients with prevalent atrial fibrillation were included in the dataset (1266 patients on apixaban matched with 3797 patients without anticoagulation), results were qualitatively similar to those observed in the incident population (Supplemental Table 6). In this larger dataset, no significant difference was observed between the two apixaban dose regimens with respect to the primary or secondary outcomes. The incidence of the primary outcome was similar among patients treated with either apixaban dose or patients who did not receive any anticoagulation. A higher rate of fatal or intracranial bleeding was observed with both apixaban doses compared with no treatment (HR, 5.14; 95% CI, 2.72 to 9.72; P<0.001 with the standard dose and HR, 2.63; 95% CI, 1.25 to 5.55; P=0.01 with the reduced dose). We also studied the effect of apixaban in different strata. These hypothesis-generating analyses are shown in Supplemental Table 7.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the effect of apixaban compared with no treatment in patients on maintenance dialysis with atrial fibrillation. The incidence of the primary outcome was similar in patients treated with apixaban compared with no treatment. Although a trend toward fewer ischemic strokes was seen with apixaban, it was offset by a trend toward more hemorrhagic strokes in these patients. In addition, we found that apixaban was associated with higher incidence of fatal or intracranial bleeding events and a similar incidence of clinically important bleeding, compared with no treatment. Furthermore, significantly higher rates of the primary outcome, of fatal or intracranial bleeding, and of hemorrhagic stroke were seen in the subgroup of patients treated with the standard apixaban dose but not in patients who received the reduced apixaban dose, compared with no treatment.

Comparison of apixaban with warfarin in the dataset by Siontis et al. (6) did not demonstrate any difference in the incidence of stroke, and several cohort studies of similar design failed to show any benefit from warfarin in ESKD (8,14–17). The lower mortality among apixaban users suggests that our results are unlikely to be confounded by selection of sicker patients at higher risk of stroke to receive apixaban while lower-risk patients are selected for no treatment. Stroke mechanisms seem to be different in patients with kidney failure, with higher relative incidence of hemorrhagic stroke potentially accounting for the similar incidence of any stroke observed with anticoagulant agents or no treatment.

Furthermore, the standard apixaban dose was associated with a higher incidence of the primary outcome compared with no treatment. This result is in contrast with recently reported superiority of the standard-dose regimen compared with warfarin for stroke prevention and is due to the higher incidence of hemorrhagic stroke among patients on apixaban at the standard dose compared with no anticoagulation (6). Methodological differences between the two studies may explain this discrepancy: incident versus prevalent population, warfarin versus no anticoagulation for control group, and only ischemic stroke versus any stroke for the outcome of interest.

DOACs have been used in patients with recent acute coronary syndromes or stable coronary artery disease on the top of antiplatelet therapy in an attempt to improve cardiac mortality or adverse cardiovascular events. Low-dose apixaban and rivaroxaban have been associated with numerically lower or significantly lower cardiovascular event rates, respectively, at the expense of more fatal or intracranial bleeding events (18,19). In our analysis, no significant difference was observed between the standard apixaban dose and no anticoagulation with respect to a composite outcome of myocardial infarction or ischemic stroke. On the contrary, a higher rate of myocardial infarction or ischemic stroke was seen with reduced-dose apixaban compared with no treatment. A pharmacologic study in hemodialysis showed that patients on reduced-dose apixaban were close to the tenth percentile of the predicted therapeutic level for the area under the curve, trough, and peak levels seen with the standard dose in patients with preserved kidney function, possibly accounting for more ischemic events with reduced-dose apixaban in this setting (5). Nevertheless, there is no established indication for DOACs use for cardiovascular event prevention in kidney failure, at least at this time.

Our observation of lower all-cause mortality among apixaban users compared with no treatment is probably due to selection bias, with “healthier” patients being prescribed apixaban and between-group differences not fully accounted for despite propensity-score matching and adjustment for stroke or bleeding risk scores. The lower incidence of pneumonia or hip fracture among apixaban users supports this hypothesis. It will be important to assess these alternative possibilities, preferably in randomized trials, before any recommendations on use of apixaban for the reduction of mortality can be considered. Moreover, if “healthier” patients were prescribed apixaban in this cohort, stroke and fatal or intracranial bleeding outcomes could be even worse with apixaban compared with no treatment in a randomized setting.

Apixaban has been shown to be safer than warfarin in patients on maintenance hemodialysis with respect to major bleeding events, both at the standard dose and the reduced dose (6). In our analysis, despite being associated with a nonsignificant reduction in ischemic stroke, apixaban was associated with a significantly higher risk of fatal or intracranial bleeding and of hemorrhagic stroke compared with no treatment. This finding was observed in the subgroup of patients who received the standard but not the reduced apixaban dose. Fewer clinically significant bleeding events were observed with the reduced dose compared with the standard dose, as expected from pharmacokinetic data (5). However, bleeding events were observed at very high rates even without anticoagulation, suggesting prudence with anticoagulant agents in this population.

Our study had important limitations. It is an observational retrospective cohort study using diagnostic codes (20). The number and proportion of patients treated with apixaban were small, suggesting that these were “unusual” patients. The last year of data is 2015 and probably reflects an earlier era with possibly greater challenges of treatment selection. Although patients in both groups were propensity-score matched without important differences in baseline characteristics, between-group differences may not be fully accounted for with this approach. Residual confounding and selection bias may explain part of the results. Aspirin use may differ between apixaban users and nonusers and could not be captured in this cohort. We did not have any information on important confounders, such as BP control, body mass index, residual kidney function, dialysis prescription, or anticoagulation prescription during dialysis. Nevertheless, inclusion of patients with new-onset atrial fibrillation, similar results in the intention-to-treat and as-treated analyses, and exclusion of patients who died within a short interval postdiagnosis, suggesting atrial fibrillation in the setting of a serious intercurrent illness, are important strengths of our analysis. In addition, use of competing risk models has been recently shown to be critically important in the analysis of atrial fibrillation data and is another strength of this study (21).

A randomized trial with apixaban at the standard dose versus warfarin had to terminate enrollment due to slower than anticipated recruitment (NCT02942407). A second trial is currently ongoing with apixaban at the reduced dose versus warfarin in patients on maintenance hemodialysis with atrial fibrillation (NCT02933697) and will provide important information. Another randomized study will compare apixaban at the standard dose, warfarin, and no anticoagulation in this population (NCT03987711). However, our results suggest that a randomized trial comparing both apixaban doses with no anticoagulation is of utmost importance in this population. Awaiting randomized data, prudence in prescribing apixaban to patients on maintenance dialysis, especially at the standard dose, is warranted.

Disclosures

Dr. Charytan reports grants from Medtronic/Covidien and personal fees from PLC Medical, Astra Zeneca, Allena Pharmaceuticals, Medtronic/Covidien, Amgen, Merck, Zoll Medical, Fresenius, Daichi Sankyo, Novo Nordisk, Gilead, and Janssen outside the submitted work. Dr. Garlo reports employment by Alexion Pharmaceuticals since September 2018 outside the submitted work. Dr. Mavrakanas has nothing to disclose.

Funding

Dr. Garlo was supported by American Heart Association Mentored Clinical and Population Research Award 17MCPRP33661217. Dr. Mavrakanas received salary support from University of Geneva (Faculty of Medicine).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Ms. Bridget Neville for creating dataset arrays from primary data.

Preliminary results from this work were presented at the Canadian Society of Nephrology Annual General Meeting in Montreal, Canada on May 3, 2019. Final results were presented at the American Society of Nephrology Kidney Week on November 7, 2019 in Washington, DC.

The data reported here have been supplied by the US Renal Data System. The interpretation and reporting of these data are the responsibility of the authors and in no way should be seen as an official policy or interpretation of the US Government.

Because D.M. Charytan is an Associate Editor of the Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology, he was not involved in the peer review process for this manuscript. Another editor oversaw the peer review and decision-making process for this manuscript.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

Supplemental Material

This article contains the following supplemental material online at http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2215/CJN.11650919/-/DCSupplemental.

Supplemental Table 1. Condition-specific International Classification of Diseases, ninth and tenth revisions diagnostic codes used in this study.

Supplemental Table 2. Time to event data for each outcome in the apixaban and no anticoagulation groups.

Supplemental Table 3. Baseline characteristics of the unmatched and matched cohorts for patients on hemodialysis.

Supplemental Table 4. Clinical outcomes for patients on hemodialysis.

Supplemental Table 5. Sensitivity analyses.

Supplemental Table 6. Clinical outcomes in the prevalent atrial fibrillation dataset.

Supplemental Table 7. Effect of apixaban on any stroke, transient ischemic attack, or systemic thromboembolism and on major bleeding in selected strata (prevalent atrial fibrillation dataset).

References

- 1.Roy-Chaudhury P, Tumlin JA, Koplan BA, Costea AI, Kher V, Williamson D, Pokhariyal S, Charytan DM; MiD investigators and committees : Primary outcomes of the Monitoring in Dialysis Study indicate that clinically significant arrhythmias are common in hemodialysis patients and related to dialytic cycle. Kidney Int 93: 941–951, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dahal K, Kunwar S, Rijal J, Schulman P, Lee J: Stroke, major bleeding, and mortality outcomes in warfarin users with atrial fibrillation and chronic kidney disease: A meta-analysis of observational studies. Chest 149: 951–959, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chan KE, Edelman ER, Wenger JB, Thadhani RI, Maddux FW: Dabigatran and rivaroxaban use in atrial fibrillation patients on hemodialysis. Circulation 131: 972–979, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chan KE, Giugliano RP, Patel MR, Abramson S, Jardine M, Zhao S, Perkovic V, Maddux FW, Piccini JP: Nonvitamin K anticoagulant agents in patients with advanced chronic kidney disease or on dialysis with AF. J Am Coll Cardiol 67: 2888–2899, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mavrakanas TA, Samer CF, Nessim SJ, Frisch G, Lipman ML: Apixaban pharmacokinetics at steady state in hemodialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol 28: 2241–2248, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Siontis KC, Zhang X, Eckard A, Bhave N, Schaubel DE, He K, Tilea A, Stack AG, Balkrishnan R, Yao X, Noseworthy PA, Shah ND, Saran R, Nallamothu BK: Outcomes associated with apixaban use in patients with end-stage kidney disease and atrial fibrillation in the United States [published correction appears in Circulation 138: e425, 2018]. Circulation 138: 1519–1529, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.United States Renal Data System : 2017 USRDS Annual Data Report: Epidemiology of Kidney Disease in the United States, Bethesda, MD, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shen JI, Montez-Rath ME, Lenihan CR, Turakhia MP, Chang TI, Winkelmayer WC: Outcomes after warfarin initiation in a cohort of hemodialysis patients with newly diagnosed atrial fibrillation. Am J Kidney Dis 66: 677–688, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martinez BK, Sood NA, Bunz TJ, Coleman CI: Effectiveness and safety of apixaban, dabigatran, and rivaroxaban versus warfarin in frail patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. J Am Heart Assoc 7: e008643, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tsu LV, Berry A, Wald E, Ehrlich C: Modified HAS-BLED score and risk of major bleeding in patients receiving dabigatran and rivaroxaban: A retrospective, case-control study. Consult Pharm 30: 395–402, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Normand ST, Landrum MB, Guadagnoli E, Ayanian JZ, Ryan TJ, Cleary PD, McNeil BJ: Validating recommendations for coronary angiography following acute myocardial infarction in the elderly: A matched analysis using propensity scores. J Clin Epidemiol 54: 387–398, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fine JP, Gray RJ: A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. J Am Stat Assoc 94: 496–509, 1999 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhou Z, Rahme E, Abrahamowicz M, Pilote L: Survival bias associated with time-to-treatment initiation in drug effectiveness evaluation: A comparison of methods. Am J Epidemiol 162: 1016–1023, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shah M, Avgil Tsadok M, Jackevicius CA, Essebag V, Eisenberg MJ, Rahme E, Humphries KH, Tu JV, Behlouli H, Guo H, Pilote L: Warfarin use and the risk for stroke and bleeding in patients with atrial fibrillation undergoing dialysis. Circulation 129: 1196–1203, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chan KE, Lazarus JM, Thadhani R, Hakim RM: Warfarin use associates with increased risk for stroke in hemodialysis patients with atrial fibrillation. J Am Soc Nephrol 20: 2223–2233, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wizemann V, Tong L, Satayathum S, Disney A, Akiba T, Fissell RB, Kerr PG, Young EW, Robinson BM: Atrial fibrillation in hemodialysis patients: Clinical features and associations with anticoagulant therapy. Kidney Int 77: 1098–1106, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Winkelmayer WC, Liu J, Setoguchi S, Choudhry NK: Effectiveness and safety of warfarin initiation in older hemodialysis patients with incident atrial fibrillation. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 6: 2662–2668, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alexander JH, Becker RC, Bhatt DL, Cools F, Crea F, Dellborg M, Fox KA, Goodman SG, Harrington RA, Huber K, Husted S, Lewis BS, Lopez-Sendon J, Mohan P, Montalescot G, Ruda M, Ruzyllo W, Verheugt F, Wallentin L; APPRAISE Steering Committee and Investigators : Apixaban, an oral, direct, selective factor Xa inhibitor, in combination with antiplatelet therapy after acute coronary syndrome: Results of the Apixaban for Prevention of Acute Ischemic and Safety Events (APPRAISE) trial. Circulation 119: 2877–2885, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Connolly SJ, Eikelboom JW, Bosch J, Dagenais G, Dyal L, Lanas F, Metsarinne K, O’Donnell M, Dans AL, Ha JW, Parkhomenko AN, Avezum AA, Lonn E, Lisheng L, Torp-Pedersen C, Widimsky P, Maggioni AP, Felix C, Keltai K, Hori M, Yusoff K, Guzik TJ, Bhatt DL, Branch KRH, Cook Bruns N, Berkowitz SD, Anand SS, Varigos JD, Fox KAA, Yusuf S; COMPASS Investigators : Rivaroxaban with or without aspirin in patients with stable coronary artery disease: An international, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 391: 205–218, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thigpen JL, Dillon C, Forster KB, Henault L, Quinn EK, Tripodis Y, Berger PB, Hylek EM, Limdi NA: Validity of international classification of disease codes to identify ischemic stroke and intracranial hemorrhage among individuals with associated diagnosis of atrial fibrillation. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 8: 8–14, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Findlay M, MacIsaac R, MacLeod MJ, Metcalfe W, Sood MM, Traynor JP, Dawson J, Mark PB: The association of atrial fibrillation and ischemic stroke in patients on hemodialysis: A competing risk analysis. Can J Kidney Health Dis 6: 2054358119878719, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.