INTRODUCTION

Many discussions about assessing the risk of COVID-19 center around three possible outcomes: (1) avoiding infection altogether, (2) contracting COVID-19 illness and recovering, and (3) contracting COVID-19 illness and dying. Another outcome must be considered: contracting COVID-19 illness, surviving, and living with its sequelae, or aftereffects.

Research on the aftereffects of COVID-19 is emerging, but predictions can be made from similar coronaviruses such as severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS). Looking ahead to what COVID-19 aftereffects may portend for the general population of survivors is one aspect of the present paper. Yet COVID-19 sequelae hold special, and potentially devastating, risks for singers. These risks should be considered by all persons who sing, whether they are professional performers, professional singing teachers, or avocational singers, for whom weekly choir practices are a source of social connection and community cohesion.

This paper offers an in-depth discussion of the following:

-

1.

COVID-19 demographic risks

-

2.

Singers and aerosol transmission of SARS-CoV-2

-

3.

Lasting lung damage/respiratory sequelae

-

4.Laryngeal and nonrespiratory sequelae

-

4.1.Intubation-related vocal-fold injuries

-

4.2.Postviral vocal fold paralysis or paresis

-

4.3.Postviral laryngeal sensory neuropathy

-

4.4.Chronic fatigue disorders

-

4.1.

-

5.Risk assessment

-

5.1.COVID-19 screening app

-

5.2.Online survival calculator

-

5.3.Risk assessment tool

-

5.4.Decision assistance tool

-

5.1.

1. COVID-19 demographic risks

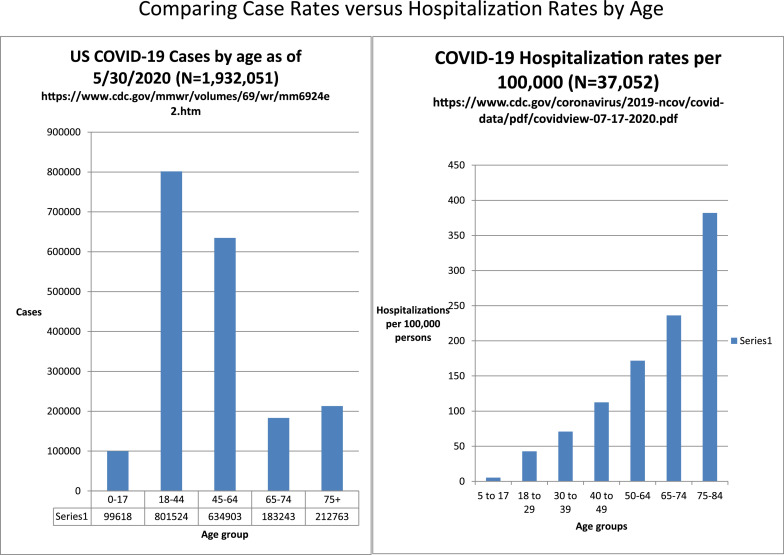

According to the Centers for Disease Control, persons 65 and older, or persons with chronic lung disease, moderate to severe asthma, serious heart conditions, immunocompromising conditions (cancer treatment, smoking, transplant recipients, immune deficiencies, HIV/AIDS, and long term use of steroids), obesity, sickle cell disease, type 2 diabetes, chronic kidney disease, or liver disease are at higher risk than the rest of the population.1 , 2 The number of people contracting COVID-19 varies with age. In general, younger people are more likely to contract COVID-19, as they are more socially active and represent a larger portion of the workforce than older persons.3 , 4 However, the risk of having a more severe case of COVID-19 increases with age, particularly above age 50.3 , 5 This contrast between case numbers by age and complications by age (as seen through hospitalization rates) is shown in Figure 1 . As of this writing, CDC statistics on case numbers by age have not been updated since May 30, 2020.

FIGURE 1.

Case numbers versus complications.

Certain ethnic groups have higher hospitalization rates than others. Non-Hispanic American Indian or Alaska Native persons have a hospitalization rate approximately 5.6 times that of non-Hispanic White persons, while non-Hispanic Black persons and Hispanic or Latino persons have a hospitalization rate approximately 4.6 times that of non-Hispanic White persons.5 It is thought that these differences in hospitalization rates (which would signify a more severe case of the disease) are not due to genetic differences between the groups, but rather health disparities, such as access to quality care. Women make up a slightly larger number of the total cases than men, according to the CDC's statistics, but men are more likely to need hospitalization, are more likely to be admitted to an ICU, and are more likely to die from COVID-19 (Table 1 ).

TABLE 1.

Differences by Gender

| Gender (All Cases) | Cases Per 100K | Hospitalization Percentage | Admit to ICU | Died |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 401.1 | 16% | 3% | 6% |

| Female | 406 | 12% | 2% | 5% |

Data from 1,320,488 laboratory confirmed COVID-19 cases reported to the CDC January 22-May 30, 2020.

Men are more likely to be hospitalized, and have slightly higher rates for severe complications (ICU admissions) and death than women.

Source: Reprinted with permission from ref. 3.

Persons 40–69 years of age should be on guard, as this age group still has a high percentage of cases and an increased risk of hospitalization for COVID-19 than younger people. Many aspiring or active professional performers are in the 18–44-year age group which has the highest number of cases. The 40–69-year age range is also one in which other health complications (due to lifestyle and genetic factors) are more prevalent than in younger people. High blood pressure, diabetes, heart disease, kidney problems, and obesity increase the risk for complications requiring hospitalization and possibly intensive care. Persons who are from higher risk ethnic/racial groups who also have other health conditions need to be especially cautious, as do those individuals living in states currently experiencing rapid case growth.

2. Singers and aerosol transmission of SARS-CoV-2

SARS-CoV-2 is the virus that causes COVID-19. It can be transmitted in one of three ways: (1) direct contact, (2) indirect contact, or (3) airborne particles. Direct contact transmission occurs through person-to-person contact via a handshake or other touching, with subsequent self-transfer of the virus to the recipient's mucus membranes. Indirect contact occurs when viral particles land on objects in the environment that are commonly touched (the objects are referred to as “fomites” once the particles touch them, ie chairs, clothes, or shared objects) and, once acquired by a susceptible host, are self-transferred to that person's mucus membranes.6

While the Centers for Disease Control continue to list droplet and close proximity as the primary route of spread of SARS-CoV-2, more evidence is emerging that airborne transmission likely accounts for the majority of the spread of SARS-CoV-2 and occurs when particles of varying size are transmitted through the air and are inhaled into one's upper and lower respiratory tracts.7 , 8 Viral load (meaning how much virus a person is exposed to), how long an individual is exposed to a viral load, and an individual's personal susceptibility all play a contributory role in SARS-CoV-2 transmission. One viral particle may be enough to infect some people who touch a droplet and infect themselves, but recent data substantiate what has been suspected by the scientific community for some time regarding SARS-CoV-2 transmission: smaller spaces with less ventilation and higher viral load with more people present lead to higher infection rates via aerosols.8 , 9

Particles transmitted through the air are divided into two categories, droplets and aerosols. Droplets are the largest particles transmitted (larger than 5 µm), and there are more of these particles in a cough or a sneeze than in speech. Droplets fall quickly from the air in close proximity to the host and do not float through the air. Aerosols, particles smaller than droplets, transmit SARS-CoV-2 over greater distances and times because they float and can remain suspended in the air for hours. Additionally, the smaller the particle, the more likely it is to reach the lower respiratory tract when inhaled10; larger droplets are more likely to be caught in the nasal passages, larger airways and paranasal sinuses.11 Although the disease may be acquired through these structures, small particles, specifically those less than one micron, carry little virus due to their small size, but float for hours.

Most concerning are “medium-sized” particles that fall between 1 and 5 µm.12 These are produced in higher proportion during speech and singing.13 They tend to carry a higher viral load, and, once in the air, their moisture evaporates and turns them into virally concentrated “droplet nuclei."14 The medium-sized particles are able to float for hours, find the lower airways with a higher viral load per particle, and carry a higher probability than particles of other sizes or droplets of successfully infecting a susceptible host. Both small and medium-sized particles are generated from the alveoli of lungs (smallest air sacs where oxygen exchange occurs) by way of a “fluid film burst” as the alveoli open and close during breathing.15 It has been long established that breathing and speaking lead to aerosolization of particles.16 Vocal folds also have a fluid film, and their vibration likely contributes to the generation of medium-sized particles. This may be why speaking and singing produce more medium-sized aerosols and why singers might be at increased risk of transmission. Asadi et al demonstrated that increased vocal amplitude (loudness) led to increased aerosolization due to more medium-sized particles being emitted. In addition, they demonstrated that some people may be “speech superemitters” who emit particles at rates an order of magnitude higher than others for yet-to-be-determined reasons.13 A recent study using a laser particle counter demonstrated higher aerosolization rates from singing as compared to speaking among 8 professional singers.17

While not true with all viruses (specifically influenza), it was recently demonstrated that large droplets and medium-sized particles of SARS-CoV-2 are stopped by a surgical face mask (article did not specify type of surgical face mask, but was not N95 etc); however, small particles may still escape the mask into the air.18 Surgical face masks thus significantly mitigate the risk of disease spread (although by no means are the sole consideration as discussed earlier). Cloth masks of various materials also mitigate risk because they stop droplet and hopefully most medium-sized particle transmission. However, it is impossible to determine the ability of cloth masks to stop all medium-sized particles because of the masks’ heterogeneity. In a recent opinion, Dr. Malcolm Butler stated why having all persons wear a cloth mask is the next best thing to a vaccine: “When an infected person wears a mask (and remember that you are most infectious before you even start to feel sick), the total volume of virus floating around in the air that we share is dramatically reduced… the simple act of wearing a mask is enough to stop the pandemic spread."12 The virus must find a susceptible person, infect that person through a respiratory, or possibly ocular, mucosal route and then be in enough concentration to overcome their defenses.

It is important to realize that the person closest to an infected individual may not be the most at risk. Air movement in a space may blow particles away from a close individual and towards another person further away.19 Room air turnover and ventilation are key to removing floating aerosolized particles. Plexiglass between both masked and unmasked singers will catch some (but not all) droplets and medium-sized particles with potential for aerosolization. Plexiglass will not mitigate disease transmission due to continued aerosolization of the small and medium particles that escape the sides of, or travel through, cloth masks, and they may even disrupt airflow in a room's ventilation pattern which could lead to higher viral loads.20

With many SARS-CoV-2 infected individuals being asymptomatic, it is important for individuals who are older or more susceptible to infection for other reasons, or who live with someone who falls into those categories, to be cautious of asymptomatic, younger persons in individual and group settings. A recent publication on safer singing practices reports how to mitigate risk of SARS-CoV-2 transmission for singers.21

3. Lasting lung damage/ respiratory sequelae

“Chi sa respirare, sa cantare," a phrase central to Bel Canto voice pedagogy, states that “one who breathes well, sings well."22 While it is true that one cannot ascribe all singing voice problems to the breath, most pedagogues agree that the efficient use of the breath is central to healthy phonation. If the respiratory system is compromised due to illness or injury, singing can become more effortful, leading many to use potentially injurious compensatory vocal strategies. Singers and teachers of singing are vocal athletes who depend on optimal respiration.

The risks of lung disease and the respiratory sequelae of COVID-19 may be underestimated. Prior to the current pandemic, respiratory illness was remarkably common. In 2017, the Global Burden of Disease Chronic Respiratory Disease Collaborators estimated that 544.9 million people worldwide suffered disability and death due to chronic lung disease.23 Prevalence was highest (>10%–11% of the population) in wealthier countries, a finding consistent with the American Lung Association's estimate that over 35 million Americans suffer chronic, preventable, and possibly undiagnosed lung disease.24 Given that the population of the United States is roughly 331 million25 people, this represents a one-in-ten risk for chronic respiratory disease prior to COVID-19.

COVID-19 is a new disease, and studies on its long-term effects will continue to emerge. Many severe COVID-19 infections require treatment in the intensive care unit and can lead to lasting postrecovery sequelae26 including breathing, physical, cognitive, and psychological problems.27 These symptoms are referred to as postintensive care syndrome, an umbrella term for ICU sequelae that can have long-term quality of life implications.28 According to Murray et al, about 50% of patients hospitalized for COVID-19 will require some form of ongoing care to improve their long-term outcomes.29

Respiratory changes following COVID-19 are often compared to SARS and MERS pandemics.30 , 31 Chan et al studied patients who recovered from SARS and found that 6%–20% suffered muscle weakness and mild-to-moderate restrictive lung disease 6–8 weeks post discharge.32 In another study, 94 SARS survivors (about a third of the study participants) presented with persistent pulmonary function impairment at 1-year follow-up. The overall health of these SARS survivors was also significantly worse than the general population.33 Hui et al studied the long-term effects of SARS and found that 27.8% of patients had abnormal chest radiograph findings and persisting reductions in exercise capacity (6-minute walk test (6MWT)) at 12 months.34 Zhang et al reported that patients who recover from SARS can experience persistent lung damage, even 15 years later.35 COVID-19 is not as deadly as SARS or MERS, and its symptomology is more heterogenous, affecting more diverse systems.36 Nevertheless, it seems plausible that the respiratory sequelae of COVID-19 will resemble those seen following these earlier pandemics.37

Emerging studies are shaping our understanding of the respiratory effects of COVID-19. Carfi et al found that 87.4% of patients experienced at least 1 symptom following recovery, with fatigue (53%) and dyspnea/shortness of breath (43%) being the most commonly reported.38 Wang et al studied patients hospitalized with COVID-19 pneumonia. Sixty-six of the 70 patients discharged (94%) had residual disease on final CT scans, with "ground-glass" opacity the most common pattern. These lesions were dense clumps of hardened tissue blocking blood vessels within and around the alveoli.39 It is important to note that these subjects were hospitalized, implying that they had severe COVID-19 infections. These percentages may not be the same for patients with more mild disease, and further study is needed. Nevertheless, reports summarized below suggest that respiratory sequelae may occur even following COVID-19 infection in persons without severe symptoms.

In another preliminary study, LeBorgne surveyed 55 professional Broadway, national tour, and cruise ship performers who experienced COVID-19 symptom onset from March 1–31, 2020.40 Of these participants, roughly half tested positive for COVID-19 or COVID-19 antibodies, and half were unable to receive testing but had symptoms consistent with COVID-19 infection. Four percent were hospitalized and 11% were asymptomatic but tested positive. Three-month post-acute virus, 28% of participants continued to experience respiratory compromise, and 26% complained of vocal fatigue. These early findings suggest that although these elite artists survive the virus, many suffer lingering reduction of respiratory and phonatory function.

Surprisingly, one does not need to be seriously ill with COVID-19 to suffer lung damage. A study by Long et al examined 37 asymptomatic COVID-19 patients. Chest computed tomography (CT) scans of revealed lung abnormalities in 56.8% of these patients.41 These included ground-glass opacities, stripe shadows and/or diffuse consolidation similar to those found by Wang et al.

The pulmonary lesions associated with COVID-19 can cause chronic, long-lasting lung disease.42 Some lesions will gradually heal or disappear, but many will harden into layers of scar tissue called pulmonary fibrosis, and the prevalence of COVID-19 fibrotic lung disease is predicted to be high.43 Pulmonary fibrosis can stiffen the lungs, cause shortness of breath, and limit the ability to be physically active. Whereas mild or moderate reductions in respiratory function may not be debilitating for the average person, they could be career-ending for singers and teachers of singing.

4. Laryngeal and other nonrespiratory sequelae

Generally speaking, a medical condition is considered chronic if it lasts longer than 12 weeks. Thus, the array of post-COVID-19-related medical complications is just beginning to be elucidated. Beyond the respiratory/pulmonary complications described in detail above, other post COVID-19 medical conditions that affect vocal production most directly can be grouped broadly into 4 categories: (1) Intubation and cough related injury; (2) Postviral vocal fold paralysis or paresis; (3) Postviral laryngeal sensory neuropathy; and (4) Chronic fatigue.

4.1. Intubation and cough-related injury

The nature and extent of intubation and/or cough-related injury to the larynx and vocal folds associated with COVID-19 is likely similar to other conditions that require emergent and/or prolonged intubation. Thus, the prevalence is estimated to be sharply increasing.44 Chronic effects of these injuries include airway stenosis, laryngeal stenosis below, at, or above the vocal folds, vocal fold mucosal/vibration abnormalities and scarring, vocal fold fixation, and postintubation phonatory insufficiency. While each of these conditions can occur with varying degrees of severity, even mild perturbations to precise laryngeal functioning may lead to substantial functional compromise in singing. Additionally, the ability to restore full vocal function following these types of injury is limited, at best.45

4.2. Postviral vocal fold paralysis or paresis

Vocal fold paralysis and paresis can result from even short periods of intubation, and also can result from viral-related injury to the vagus nerve—one of twelve cranial nerves and the one responsible for vocal fold muscle function and sensation to part of the larynx. Other conditions also may be responsible for laryngeal nerve injury. While present understanding is nascent, patients with lower cranial neuropathies post COVID-19 including vagal nerve involvement have been reported.[46], [47], [48], [49] Presumably, the incidence of vocal fold paralysis and paresis following COVID-19 infection appears low given the prevalence of infection and the paucity of reports. However, mild vocal fold paresis in singers often leads to symptoms that might not be noticed by the general population but would be noticed by trained singers and singing teachers (such as vocal fatigue, effort, and range issues). Furthermore, access to comprehensive laryngologic evaluation, dynamic voice assessment, and strobovideolaryngoscopy has been limited by pandemic. Thus, the prevalence, severity and consequence of vocal fold paresis in singers post COVID-19 remain to be determined.

4.3. Postviral laryngeal sensory neuropathy

In addition to the motor neuropathies described above, sensory neuropathies of the larynx are associated with viral infections.50 The most common presentations of laryngeal sensory neuropathy are chronic cough and swallowing dysfunction, yet much remains unknown about this elusive condition. Studies investigating high demand vocal function in patients with sensory neuropathy of the larynx are lacking. The incidence and prevalence of laryngeal sensory neuropathy post COVID-19 is unknown but is likely to occur as it can following any viral infection. It is logical to postulate that loss of feeling and proprioception in the larynx could lead to decrease in fine motor control with adverse effects on singing capabilities, particularly among those whose work involves singing styles that demand exquisitely precise motor movement.

4.4. Chronic fatigue

Chronic fatigue is emerging as a common sequela of COVID-19 infection, and its importance for singers has been recognized.51 In several pilot studies over 53% of individuals experienced chronic fatigue associated with COVID-19.38 , 52 While not directly affecting vocal production, chronic fatigue can be associated with voice complaints. This association has been reported specifically in a study of younger singers,53 and its symptoms typically worsen after physical, mental, or emotional exertion.54 Chronic fatigue post COVID-19 may prove to be fairly common and, logically, may have a significant impact on singers with high vocal, mental, or emotional demands.

5. Risk assessment

This section contains risk assessment tools for singers and teachers of singing. These tools may assist the reader in making informed decisions about how, when, and where they will pursue singing in the months ahead.

5.1. COVID-19 screening app

The authors suggest that readers make use of a smart phone-based screening app (eg, https://www.apple.com/covid19). Such an app can be used daily to evaluate one's current health, in combination with a check of basal temperature each morning before rising. Medical help should be sought immediately by anyone who suspects that he/she might have COVID-19.

5.2. Online COVID-19 survival calculator

Several online calculators are available to readers determine their chances of contracting and surviving COVID-19. One notable example can be found at: https://www.covid19survivalcalculator.com

This calculator gives the user a detailed summary of personal risk and assists researchers by collecting data for future studies.

5.3. Risk assessment tool

Risk assessment can help estimate the likelihood of contracting COVID-19. Factors to be considered include a person's age, place of residence, occupation, use of public transit, extracurricular activities, travel history, the number of persons with whom one interacts closely, and compliance with CDC/WHO guidance on behavior. This information can be used to estimate one's probability of harm. An example calculator application can be found at http://www.mycovid19risk.com/. The likelihood that complications might result if one contracted COVID-19 depends upon such factors as age, pre-existing medical conditions, gender, ethnicity, and access to medical care. These factors help determine one's magnitude of harm. The example provided above in Section ``Online survival calculator'' https://www.covid19survivalcalculator.com/en/calculator could be used to determine magnitude of (potential) harm. Estimates of probability of harm and magnitude of harm can then be combined informally to help an individual determine his or her overall personal risk level.

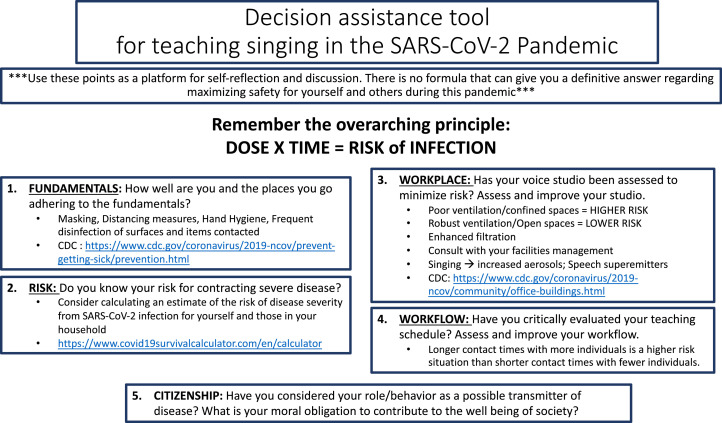

5.4. Decision assistance tool

As part of the National Association of Teachers of Singing webinar, “After COVID—Concerns for Singers” (available at https://youtu.be/xPg7FLkYDYY), the authors compiled a singer-specific “decision assistance tool.” This tool (Figure 2 below) summarizes much of what we know about the risks associated with COVID-19 and teaching singing. In general, “dose” multiplied by “exposure time” equals “risk of infection”:

FIGURE 2.

Decision assistance tool.

The risks of COVID-19 to all voice users are substantial. In addition to the multifold sequelae discussed in this article, the mental health, professional standing/employment, and finances of those who contract this disease may be compromised. For some singers, these post-COVID-19 conditions may seem worse than dying itself. As shocking as this sentiment may seem, musicians in one study who had lost the ability to play their instrument due to injury described the emotional effects as “drastic,” “traumatic'' and “devastating.” One musician stated, “it was almost like my life had stopped” while another simply explained “music's my life."55 Such problems are well known and have been discussed in other literature.56 , 57

Some singers and teachers of singing express confidence in their ability to safely contract, suffer through and emerge unscathed following COVID-19 illness. “Let's just get it and get over it” is a frequently expressed sentiment. The authors believe that voice users should seriously consider the risks of COVID-19 sequelae outlined in this paper, recognizing the warnings of physicians and other scientists that COVID-19 infection in anyone of any age can be devastating or even fatal.

Conversely, there are those who are fearful of this illness, doing everything possible to avoid contracting it. Some may be shamed into silence about expressing their fears of the workplace and may need to cite their unwillingness to risk the potential COVID-19 sequelae in an effort to come to an agreeable work arrangement with their employer. Real fears of being fired or labeled as disloyal to their enterprise likely play a significant role in the potential avoidance of this important conversation between employer and employee. In many instances, the collaboration of a knowledgeable physician may be invaluable for the employee and employer.

CONCLUSION

In assessing the risk of contracting COVID-19 illness, society must account for four, not three, possibilities. In addition to avoiding infection altogether, contracting and recovering unharmed, and contracting and dying, the fourth potential COVID-19 illness outcome—contracting and living with its potentially life and career altering after-effects—should play a prominent role in the decisions voice users make as they consider returning to the workplace.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors certify that they have NO affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial interest (such as honoraria; educational grants; participation in speakers’ bureaus; membership, employment, consultancies, stock ownership, or other equity interest; and expert testimony or patent-licensing arrangements) in the materials (eg, websites) discussed in this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Coronavirus disease 2019: who is at increased risk for severe illness. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/need-extra-precautions/people-at-higher-risk.html. Accessed July 15, 2020.

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Coronavirus disease 2019: people with certain medical conditions. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/need-extra-precautions/groups-at-higher-risk.html. Accessed July 15, 2020.

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report: Coronavirus Disease 2019 Case Surveillance—United States, January 22–May 30. 2020:759–765. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/69/wr/mm6924e2.htm. Accessed June 25, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): cases in the U.S. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/cases-updates/cases-in-us.html. Accessed June 25, 2020.

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, COVIDView: a weekly surveillance summary of U.S. COVID-19 activity. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/covid-data/pdf/covidview-07-17-2020.pdf. Accessed July 23, 2020.

- 6.Asadi S., Bouvier N., Wexler A.S., et al. 2020. The coronavirus pandemic and aerosols: does COVID-19 transmit via expiratory particles? Aerosol Sci Technol. 2020;0:1–4. doi: 10.1080/02786826.2020.1749229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, How COVID-19 spreads. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prevent-getting-sick/how-covid-spreads.html, Accessed July 6, 2020.

- 8.medRxiv, Quantitative assessment of the risk of airborne transmission of SARS-CoV-2 infection: prospective and retrospective applications. Available at: https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.06.01.20118984v1, Accessed July 10, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Morawska L, Milton DK. It is time to address airborne transmission of COVID-19. Clin Infect Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa939. https://academic.oup.com/cid/article/doi/10.1093/cid/ciaa939/5867798 [Internet] Available at: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heyder J., Gebhart J., Rudolf G., et al. Deposition of particles in the human respiratory-tract in the size range 0.005-15-mu-m. J. Aerosol Sci. 1986;17:811–825. doi: 10.1016/0021-8502(86)90035-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Paul Baron Division of Applied Technology National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Generation and Behavior of Airborne Particles (Aerosols). Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/topics/aerosols/pdfs/Aerosol_101.pdf?fbclid=IwAR0uFD71YA0gGb4w9VM2HShaEpeYRRzgDf_Xj2hL_trCnAThJBorHVEsZ30), Accessed July 5, 2020.

- 12.Wenatchee World, Opinion Dr. Malcolm Butler: why you should wear a mask (It's the air you share). Available at: https://www.wenatcheeworld.com/news/coronavirus/opinion-dr-malcolm-butler-why-you-should-wear-a-mask-it-s-the-air-you/article_998e2394-b5a1-11ea-b609-27e947f1e3fe.html, Accessed July 5, 2020.

- 13.Asadi S., Wexler A.S., Cappa C.D., et al. Aerosol emission and superemission during human speech increase with voice loudness. Sci Rep. 2019;9:2348. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-38808-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Duguid J.P. The size and the duration of air-carriage of respiratory droplets and droplet-nuclei. Epidemiol Infect. 1946;44-6:471–479. doi: 10.1017/s0022172400019288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnson G.R., Morawska L., Ristovski Z.D., et al. Modality of human expired aerosol distributions. J Aerosol Sci. 2011;42-12:839–851. doi: 10.1016/j.jaerosci.2011.07.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morawska L., Johnson G.R., Ristovski Z.D., et al. Size distribution and sites of origin of droplets expelled from the human respiratory tract during expiratory activities. J Aerosol Sci. 2009;40:256–269. doi: 10.1016/j.jaerosci.2008.11.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.D Mürbe, M Fleischer, J Lange, et al. Aerosol emission is increased in professional singing. Available at: https://depositonce.tu-berlin.de/bitstream/11303/11491/5/muerbe_etal_2020_aerosols-singing.pdf. Accessed July 24, 2020

- 18.Leung N.H.L., Chu D.K.W., EY C.Shiu, et al. Respiratory virus shedding in exhaled breath and efficacy of face masks. Nature Med. 2020;26:676–680. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0843-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wei J.J., Li Y.G. Airborne spread of infectious agents in the indoor environment. Am J Infect Control. 2016;44:102–108. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2016.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.International Coalition Performing Arts Aerosol Study, Preliminary recommendations from international performing arts aerosol study based on initial testing results. Available at: https://www.nfhs.org/media/4029971/preliminary-recommendations-from-international-performing-arts-aerosol-study.pdf. Accessed July 24, 2020.

- 21.Naunheim M.R., Bock J., Doucette P.A., et al. Safer singing during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic: what we know and what we don't. J. Voice. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jvoice.2020.06.028. https://www.jvoice.org/article/S0892-1997(20)30245-9/abstract [Internet] [cited 2020 Jul 10];0(0). Available at: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McCoy S. On breathing and support. J. Sing. 2014;70:321–324. [Google Scholar]

- 23.GBD Chronic Respiratory Disease Collaborators Prevalence and attributable health burden of chronic respiratory diseases, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2017. Lancet. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30105-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pal S. Epidemiology of chronic lung diseases. US Pharm. 2017;42:8. https://www.uspharmacist.com/article/epidemiology-of-chronic-lung-diseases Accessed June 29, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Worldometer, US Population. Available at: https://www.worldometers.info/world-population/us-population/. Accessed June 29, 2020.

- 26.Denehy L., Elliott D. Strategies for post ICU rehabilitation. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2012;18:503–508. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0b013e328357f064. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22914429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jackson J.C., Ely E.W., Morey M.C., et al. Cognitive and physical rehabilitation of intensive care unit survivors: results of the return randomized controlled pilot investigation. Crit Care Med. 2012;40:1088–1097. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182373115. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22080631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rawal G., Yadav S., Kumar R. Post-intensive care syndrome: an overview. J Transl Int Med. 2017;5:90–92. doi: 10.1515/jtim-2016-0016. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28721340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.A Murray, C Gerada, J Morris, We need a nightingale model for rehab after covid-19, 2020. Available at: https://www.hsj.co.uk/commissioning/we-need-a-nightingale-model-for-rehab-after-covid-19-/7027335.article

- 30.Herridge M.S., Cheung A.M., Tansey C.M., et al. One-year outcomes in survivors of the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:683–693. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022450. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12594312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tansey C.M., Louie M., Loeb M., et al. One-year outcomes and health care utilization in survivors of severe acute respiratory syndrome. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:1312–1320. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.12.1312. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17592106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chan K.S., Zheng J.P., Mok Y.W., et al. Sars: protgnosis, outcome and sequelae. Respirology. 2003;8(Suppl):S36–S40. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1843.2003.00522.x. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15018132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ong K-C, Ng AW-K, Lee LS-U, et al. 1-Year pulmonary function and health status in survivors of severe acute respiratory syndrome. Chest. 2005;128:1393–1400. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.3.1393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hui D.S., Wong K.T., Ko F.W., et al. The 1-year impact of severe acute respiratory syndrome on pulmonary function, exercise capacity, and quality of life in a cohort of survivors. Chest. 2005;128:2247–2261. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.4.2247. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16236881 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang P.eixun, Li J.ia, Liu H.uixin, et al. Long-term bone and lung consequences associated with hospital-acquired severe acute respiratory syndrome: a 15-year follow-up from a prospective cohort study. Bone Res. 2020;8:1–8. doi: 10.1038/s41413-020-0084-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sheehy L.M. Considerations for postacute rehabilitation for survivors of COVID-19. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2020;6:e19462. doi: 10.2196/19462. https://publichealth.jmir.org/2020/2/e19462 PMID: 32369030 PMCID: 7212817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Barker-Davies R.M., O'Sullivan O., Senaratne K.P.P., et al. The Stanford Hall consensus statement for post-COVID-19 rehabilitation. Br J Sports Med. 2020 doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2020-102596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Carfì A, Bernabei R, Landi F, Gemelli Against COVID-19 Post-Acute Care Study Group Persistent symptoms in patients after acute COVID-19 [published online ahead of print, 2020 Jul 9] JAMA. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.12603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang Y.uhui, Dong C.hengjun. Temporal changes of CT findings in 90 patients with COVID-19 pneumonia: a longitudinal study. Radiology. 2020 doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020200843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.The National Association of Teachers of Singing, After COVID – concerns for singers. Available at: https://youtu.be/xPg7FLkYDYY. Accessed July 1, 2020.

- 41.Long Q., Tang X., Shi Q., et al. Clinical and immunological assessment of asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infections. Nat Med. 2020 doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0965-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Science News, D Cox D. Some Patients Who Survive COVID-19 May Suffer Lasting Lung Damage. Sciencenews.org. https://www.sciencenews.org/article/coronavirus-covid-19-some-patients-may-suffer-lasting-lung-damage. Accessed June 29, 2020.

- 43.P George, A Wells, R Jenkins, Pulmonary fibrosis and COVID-19: the potential role for antifibrotic therapy. 2020 DOI: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30225-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 44.Piazza C., Filauro M., Dikkers F.G., et al. Long-term intubation and high rate of tracheostomy in COVID-19 patients might determine an unprecedented increase of airway stenoses: a call to action from the European Laryngological Society [published online ahead of print, 2020 Jun 6] Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2020:1–7. doi: 10.1007/s00405-020-06112-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Arviso L.C., Klein A.M., Johns MM 3rd M.M. The management of postintubation phonatory insufficiency. J Voice. 2012;26:530–533. doi: 10.1016/j.jvoice.2010.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Orsucci D., Ienco E.C., Nocita G., et al. Neurological features of COVID-19 and their treatment: a review. Drugs Context. 2020;9 doi: 10.7573/dic.2020-5-1. 2020-5-1. Published 2020 Jun 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kato V., Laure B., Harald C. Neurological manifestations of COVID-19, SARS and MERS [published online ahead of print, 2020 Jun 19] Acta Neurol Belg. 2020:1–10. doi: 10.1007/s13760-020-01412-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Aoyagi Y., Ohashi M., Funahashi R., et al. Oropharyngeal dysphagia and aspiration pneumonia following coronavirus disease 2019: a case report [published online ahead of print, 2020 Jun 12] Dysphagia. 2020:1–4. doi: 10.1007/s00455-020-10140-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Decavel P., Petit C., Tatu L. Tapia syndrome at the time of the COVID-19 pandemic: lower cranial neuropathy following prolonged intubation [published online ahead of print, 2020 Jun 9] Neurology. 2020 doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000010011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Altman K.W., Noordzij J.P., Rosen C.A., et al. Neurogenic cough. Laryngoscope. 2015;125:1675–1681. doi: 10.1002/lary.25186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stavrides K., Sataloff R.T., Emerich K. In: Professional Voice: The Science and Art of Clinical Care. Fourth ed. Sataloff R.T., editor. Plural Publ; San Diego, CA: 2017. Chronic fatigue syndrome in singers; pp. 877–883. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Qi R, Chen W, Liu S, et al. Psychological morbidities and fatigue in patients with confirmed COVID-19 during disease outbreak: prevalence and associated biopsychosocial risk factors. Preprint. medRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.05.08.20031666. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tepe E.S., Deutsch E.S., Sampson Q., et al. A pilot survey of vocal health in young singers. J Voice. 2002;16:244–250. doi: 10.1016/s0892-1997(02)00093-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) information for healthcare providers. https://www.cdc.gov/me-cfs/healthcare-providers/index.html. Accessed July 12, 2020.

- 55.Zaza Christine, Charles Cathy, Muszynski Alicja. "The meaning of playing-related musculoskeletal disorders to classical musicians. Soc Sci Med. 1998;47:2013–2023. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(98)00307-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sataloff R.T., Brandfonbrener A.G., Lederman R.J., et al. third ed. Science and Medicine; Narberth, PA: 2010. Performing Arts Medicine. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rosen D.C., Sataloff J.B., Sataloff R.T. second ed. Plural Publ; San Diego, CA: 2021. Psychology of Voice Disorders. [Google Scholar]