Abstract

This article aims to assess the impact of coronavirus (COVID-19) spread-prevention actions on water consumption, based on a case study in Joinville, Southern Brazil. Residential water consumption data, obtained through telemetry in two periods (before and after a governmental action imposing quarantine and social isolation), were analyzed. Complementarily, the analyses were also applied to the commercial, industrial and public consumption categories. For the analysis, Wilcoxon and Kruskal-Wallis non-parametric tests were applied and Prais-Winsten regression models were adjusted. The results of the Wilcoxon test show that there are significant differences between the analyzed periods, indicating a water consumption drop in the commercial, industrial and public categories, and an increase in the residential category. The regression model results confirm the effect of the restrictive actions in reducing consumption in non-residential categories. The results also indicate an increase in water consumption, which was steeper in apartment buildings than in houses, whether isolated or grouped in condominiums. A weak association was found between the variation in water consumption and the spatial distribution of buildings. Understanding water consumption related aspects is important to gather essential information to ensure the urban water supply system is resilient in a pandemic situation.

Keywords: COVID-19, Water consumption, Urban environment

1. Introduction

Water resources availability is a restrictive factor for regional socioeconomic and environmental development (Wei et al., 2018). Furthermore, access to water for domestic use is indispensable for promoting public health (Sorenson et al., 2011). Currently, the urbanization and industrialization processes make the discrepancy between water demand and the increasing shortage of water resources more evident (Wei et al., 2018). Issues related to water consumption are a growing challenge in terms of sustainability, especially in developing countries, although reaching sustainable water resources development is a matter of global importance (Wang and Wang, 2020).

A stable supply of drinkable water plays an important role in ensuring the health of a population, especially during the outbreak of epidemic diseases, when water-demanding measures, like washing hands, are essential to prevent the spread of the virus (Lau et al., 2009; WHO, 2015). Regarding COVID-19, the enforcement of social distancing and the interruption of intra-municipal public transportation, as well as the closure of entertainment venues, are associated with reductions in the incidence of cases (Tian et al., 2020). Nonetheless, the best approach to a pandemic without an effective medicine is the quarantine (Huang and Qiao, 2020). Pharmacological treatments for COVID-19 are still not known (Cortegiani et al., 2020). With that in mind, authorities in many parts of the World took measures to implement quarantine and social distancing, such as school closure, suspension of public transportation services and temporary prohibition of public gatherings and non-essential economic activities.

Making sure the population has access to clean water is a challenge faced by several countries during the COVID-19 pandemic (Brauer et al., 2020). Also, the behavioral changes needed to contain the pandemic can provide useful information for transformations towards more sustainable supply and production (Sarkis et al., 2020). Understanding the impact of disease-containment actions on water consumption provides solid information for policy makers to plan and set the right priorities to successfully overcome the challenge. The objective of this article is to evaluate how the COVID-19 spread-prevention actions are affecting urban water consumption. The main contribution of this study is the assessment of water consumption during a pandemic, providing information for the management of water supply systems in order to be resilient in challenging situations for the society. In addition, the research evaluates fluctuations in water consumption by category and provides subsidies for more accurate planning of production and operation of water supply systems. In terms of innovation, to the best of the authors' knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate the effects of COVID-19 spread-prevention actions on water consumption. The content of this paper is organized in the following manner: in Section 2, materials and methods are presented. Results and discussion are in Section 3. Finally, Section 4 presents the conclusions that can be drawn from this study.

2. Material and methods

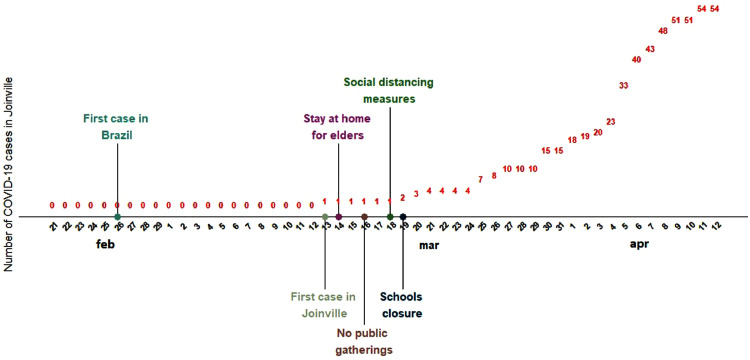

The assessment of the impact of coronavirus (COVID-19) spread-prevention actions on daily urban water consumption was performed using data acquired with a water metering telemetry system. Water consumption data in the periods before and after the social-distancing government decree in the State of Santa Catarina were analyzed. The number of COVID-19 cases and the actions taken in Joinville, Southern Brazil, are displayed in a timely manner on Fig. 1 .

Fig. 1.

Timeline showing the measures to implement quarantine and social distancing, alongside with the increase in the number of cases of COVID-19.

Water consumption data were remotely collected by telemetry, using IoT sensors connected to the water consumption meters installed in the water distribution system of each building. The telemetry-acquired water volume represents 17% of the total water consumption in the city of Joinville. Data were collected from Feb-21, 2020 to Apr-12, 2020, totaling 64,376 measurements of daily water consumption, which means water consumption data from the 26 days before and 26 days after the government decree that suspended non-essential activities, were analyzed. The population is characterized by all active water connections (N = 154,562) in the city, divided into the following categories: residential (N = 141,106), commercial (N = 11,637), industrial (N = 1266) and public (N = 553). The sample corresponds to the consumers whose water consumption is measured through telemetry (n = 1178). The sample size by category is: residential (n = 913); commercial (n = 159); industrial (n = 58) and public consumer units (n = 48).

Residential water consumption data refer to houses, apartment buildings and condominiums. The commercial category considers the sum of water consumption in shopping malls, stores, restaurants, hotels, grocery stores and other service providers. The industrial category includes factories and industrial parks. Water consumption in the public category includes schools, hospitals and other governmental facilities. The analysis is performed considering the total daily water consumption in each category.

Descriptive statistics were calculated for each category: mean, standard deviation median and interquartile range. The Shapiro-Wilk normality test (Ghasemi and Zahediasl, 2012) was used to verify the normality in the distribution of water consumption data. In order to compare water consumption data in both periods, a non-parametric paired Wilcoxon test was applied (Wilcoxon, 1992; Deyà-Tortella et al., 2017; Tian et al., 2019). The Wilcoxon test was used as industrial and residential consumption data were non-normally distributed. Although commercial and public data were normally distributed, the Wilcoxon test was also used, once non-parametric tests can be applied with no assumptions about the distribution, with relatively small effectiveness loss (Ross, 2017).

In addition, linear regression was used to evaluate water consumption in the period before and after the social isolation enforcement measures. As the analysis relates to a time series, the Prais-Winsten ordinary least-squares regression approach was used to adjust the autocorrelation (Bence, 1995; Booysen et al., 2019). The WO test was applied to identify if the series presented seasonality (Ollech, 2019).

The regression results were assessed through residue distribution analysis, as well as the variance, the presence of outliers and serial correlation (Hyndman and Athanasopoulos, 2018). The Kruskal-Wallis H test was used to analyze the variation of residential water consumption considering the different types of buildings (houses, apartment buildings and condominiums), since the assumptions required by the ANOVA test were not achieved (Vargas et al., 2018). For the analysis of household location data, spatial statistics techniques were used, presented in the form of indexes that measure the spatial association. Spatial autocorrelation was measured using the global Moran's I index, which ranges from −1 to +1 and quantifies the degree of autocorrelation (André and Carvalho, 2014). All statistical analyses were performed using R version 3.6.3 (R CORE TEAM, 2020), ggplot2 (Wickham, 2016), forecast (Hyndman and Khandakar, 2008), seastests (Ollech, 2019), pmcmr (Pohlert, 2014), sf (Pebesma, 2018), spdep (Bivand and Wong, 2018), Tmap (Tennekes, 2018) and prais (Mohr, 2019) packages. The adopted level of significance was

3. Results and discussion

Joinville is the most industrialized (Andrés et al., 2018) and populous city in the Santa Catarina state (Cureau and Ghisi, 2020), Southern Brazil. According to the last census, Joinville has 515,288 inhabitants and the average number of residents in occupied private dwellings is 3.19 (IBGE, 2010). The climate of Joinville is classified as warm temperature, fully humid, with hot summer (Kottek et al., 2006). Joinville has the highest GDP in the state of Santa Catarina and the 29th highest GDP among Brazilian cities (IBGE, 2010). The Human Development Index of the city is 0.809 (IBGE, 2010).

Sample descriptive statistics are presented (Table 1 ), divided by consumer category (residential, commercial, industrial and public). Water consumption data are presented in two periods, before and after the implementation of COVID-19 spread-prevention actions.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of water consumption (m³/day) for each category.

| Category | Before | After |

|---|---|---|

| (Feb-21 Mar-17) | (Mar-18 Apr-12) | |

| Commercial | ||

| Mean ± SD | 2089.0 ± 340.0 | 1209.0 ± 356.0 |

| Median | 2062.0 | 1174.0 |

| Interquartile Range | 297.0 | 612.0 |

| Industrial | ||

| Mean ± SD | 3657.0 ± 1152.0 | 1712.0 ± 1055.0 |

| Median | 3772.0 | 1350.0 |

| Interquartile Range | 1321.0 | 1438.0 |

| Public | ||

| Mean ± SD | 1073.0 ± 265.6 | 754.0 ± 269.2 |

| Median | 1117.0 | 791.0 |

| Interquartile Range | 399.0 | 318.0 |

| Residential | ||

| Mean ± SD | 8145.0 ± 1030.7 | 9046.5 ± 811.7 |

| Median | 8015.1 | 8785.4 |

| Interquartile Range | 1600.0 | 1371.8 |

| Overall | ||

| Mean ± SD | 14861.3 ± 2271.3 | 12681.5 ± 3245.8 |

| Median | 14984.4 | 12269.8 |

| Interquartile Range | 2574.1 | 3245.2 |

*SD: Standard Deviation.

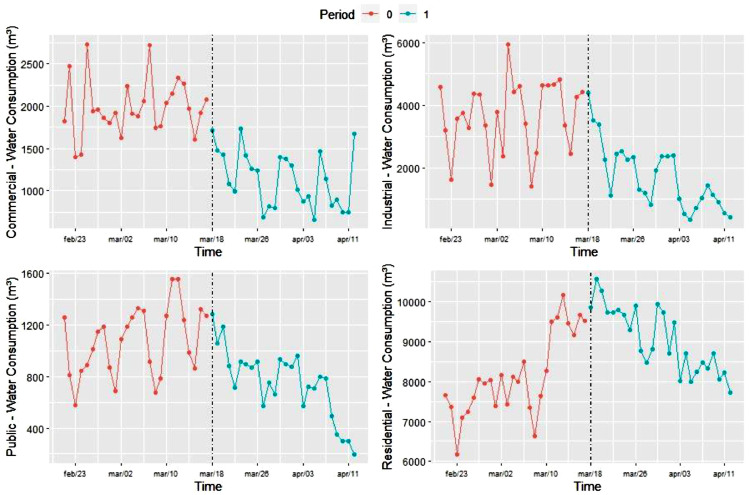

The industrial water consumption had the strongest reduction, considering the percentual variation of the mean water consumption (53% from the first to the second period). The opposite effect was caused on residential water consumption, resulting in an increase of 11%. Fig. 2 shows the graphs displaying the water consumption series in the residential, commercial, public and industrial categories. The residential consumption starts increasing even before the quarantine period begins. Nevertheless, all the categories seem to be affected by the measures put in place to restrict the spread of the pandemic.

Fig. 2.

Water consumption series in the residential, commercial, public and industrial categories before (0) and after (1) the implementation of COVID-19 spread-prevention measures.

The existence of lower or higher consumption values on certain dates is evident in Fig. 2, especially in the period before the implementation of COVID-19 spread-prevention measures. In the industrial and public categories, the lowest consumption values occur on weekends, pointing to a seasonal behavior. Concerning the residential category, the lowest consumption values in the first period of analysis can be explained by two long holidays, namely, Carnival (Feb 22–25) and city anniversary (Mar 7–9), during which many people travel away, especially to the coast. The dynamics of the commercial category is more complex. While there are some types of establishment that operate only on a weekday basis, others, like shopping malls, are busier on the weekends. However, the highest commercial water consumption values can also be related to the days before and after those holidays. The daily water demand variation can be modified according to climatic issues, weekend and holiday patterns, as well as regular residential and non-residential activities of consumers (Zhou et al., 2002).

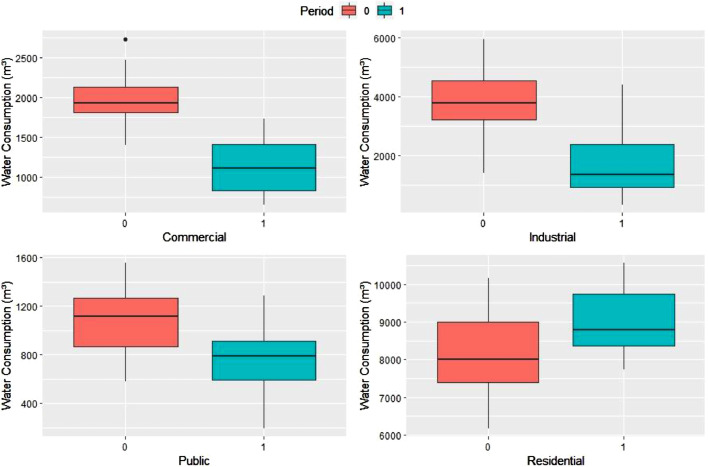

The results obtained for the Wilcoxon test were: commercial water consumption (p < 0.001); industrial water consumption (p < 0.001); public water consumption (p < 0.001); residential water consumption (p < 0.001), which allows the conclusion that there are differences in water consumption per category in the periods before (Feb-21 Mar-17) and after (Mar-18 Apr-12) the social isolation measures. When the overall consumption is considered, the result obtained for the Wilcoxon test is p = 0.0015. Fig. 3 shows the boxplot graphs of water consumption in both periods. The reduction in consumption for commercial, industrial and public categories can be seen. In the residential category, there is a possible increase in water consumption.

Fig. 3.

Water consumption boxplots before (0) and after (1) the implementation of measures to prevent contagion by COVID-19.

Table 2 shows the results of the adjusted regression models. The public and residential series, as well as the overall series, presented seasonality and required seasonal adjustment, which was conducted by means of the classic additive decomposition (Hyndman and Athanasopoulos, 2018). The results confirm what could be seen in the graphs presented in Figs. 2 and 3. There was a significant reduction in water consumption for commercial, industrial and public activities. Despite the positive signal of the parameter related to the dummy variable for the period (before and after the prevention measures), indicating a possible increase in residential water consumption, it was not significative. Likewise, the dummy variable for the overall series presented a negative signal, which could be indicating a possible decrease. However, it was not significative either.

Table 2.

Estimates of the Prais-Wisten regression on water consumption.

| Constant | Dummy (Period) | R² | Conclusion | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Commercial | 2086.42 (76.63) | *** | −871.26(108.05) | *** | 0.57 | Decreasing |

| Industrial | 3660.55 (232.67) | *** | −1870.97 (321.44) | *** | 0.44 | Decreasing |

| Public | 1027.11(95.68) | *** | −228.13 (117.30) | * | 0.24 | Decreasing |

| Residential | 8280.48 (430.94) | *** | 432.53 (442.37) | 0.36 | - | |

| Overall | 14542.44(793.13) | *** | −1457.06(948.86) | 0.36 | – |

Notes: (*), (**), and (***) denote statistical significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% levels, respectively. The values in parentheses are standard errors.

The analysis of the behavior of the residential water consumption curve indicates an increase in consumption prior to the restriction measures. The difference between the two periods, detected by the Wilcoxon test, is visible in Fig. 2 and can be also seen in the boxplot of residential water consumption (Fig. 3). However, when modeling the time series, the mentioned increase preceding the restriction measures is captured by the model, influencing the estimation of the equation parameters. The first case of COVID-19 in the city was notably notified in the week before. The raise in residential water consumption might not be due to the governmental restriction measure only. The increase in previous weeks can result from cleaning procedures and, furthermore, the citizens, especially those in the group of risk, may have chosen to remain in their homes, avoiding public activities. In addition, some companies adopted home-office practices before the state decree. These factors may have contributed to the increase in residential water consumption before that moment, which agrees with the findings of Zhong et al. (2020) and Roy et al. (2020) in their studies in other countries. For Zhong et al. (2020) most Chinese residents took precautions, avoiding crowded places, to prevent an infection by COVID-19. For the authors, those practices could be first attributed to the strict control measures implemented by local governments, but could also be the result of the residents' knowing of the COVID-19 high infectivity. Roy et al. (2020) stated that in India there is a positive public attitude towards social-distancing, avoiding gatherings and traveling.

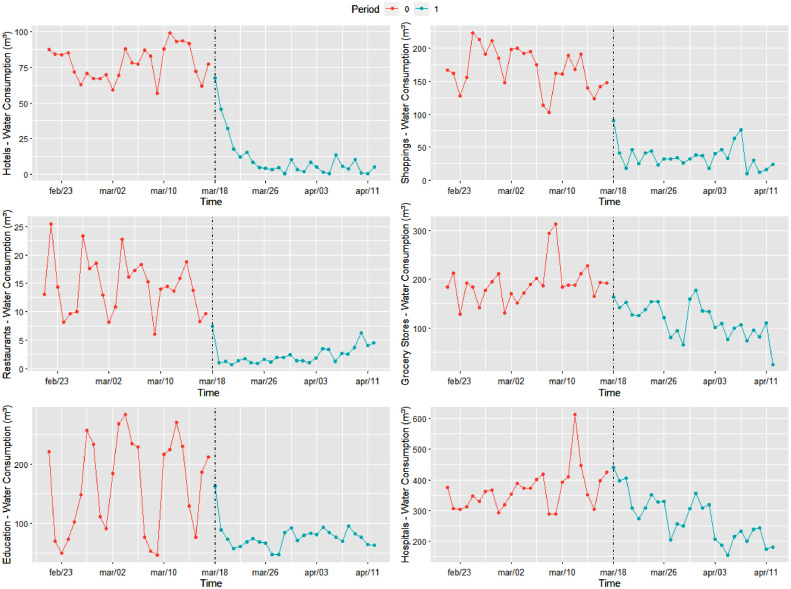

3.1. Non-residential water consumption

Although the water consumption of all non-residential categories decreased, they were affected differently, depending on the area. This can be observed in Fig. 4 , which shows the sum of water consumption for different types of buildings.

Fig. 4.

Variation of water consumption of non-residential consumers separated by different areas.

While hotels and shopping malls were not allowed to operate, schools and universities were closed and restaurants only opened for food delivery, grocery stores had permission to operate normally (Santa Catarina, 2020). Hospitals are an interesting case because, despite the outbreak of the pandemic, social distancing and stay-home measures may be lowering the number of other accidents that require medical help. On top of that, most of the regular medical procedures that are not emergencies were suspended (Joinville, 2020). Moreover, as Fig. 1 shows, the official number of COVID-19 cases are still low in the city. As in other countries, these numbers are possibly underestimated due to testing limitations (Singhal, 2020). According to Lee (2020), low and middle income countries have weaker health-care systems, laboratory resources may be lacking, and the notification of infectious diseases are often incomplete and not timely. The variation in water consumption before and after the implementation of COVID-19 spread-prevention actions in some activity sectors is presented in Table 3 .

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics of water consumption (m³/day) in non-residential buildings per activity sector.

| Activity sector | Before | After |

|---|---|---|

| (Feb-21 Mar-17) | (Mar-18 Apr-12) | |

| Hotels (n = 5) | ||

| Mean ± SD | 77.82 ± 11.63 | 11.03 ± 15.37 |

| Median | 77.60 | 5.15 |

| Interquartile Range | 17.85 | 8.3 |

| Shoppings (n = 3) | ||

| Mean ± SD | 168.45 ± 31.83 | 35.94 ± 18.62 |

| Median | 167.32 | 33.01 |

| Interquartile Range | 43.79 | 16.99 |

| Restaurants (n = 4) | ||

| Mean ± SD | 14.48 ± 4.96 | 2.38 ± 1.71 |

| Median | 14.20 | 1.75 |

| Interquartile Range | 7.33 | 2.00 |

| Grocery Stores (n = 6) | ||

| Mean ± SD | 191.96 ± 41.07 | 115.38 ± 36.00 |

| Median | 188.43 | 115.27 |

| Interquartile Range | 26.85 | 46.75 |

| Education (n = 24) | ||

| Mean ± SD | 164.46 ± 79.88 | 77.97 ± 21.47 |

| Median | 185.14 | 75.76 |

| Interquartile Range | 148.38 | 16.55 |

| Hospitals (n = 8) | ||

| Mean ± SD | 366.79 ± 67.88 | 276.04 ± 77.09 |

| Median | 364.20 | 264.71 |

| Interquartile Range | 82.47 | 118.04 |

*SD: Standard Deviation.

3.2. Residential water consumption

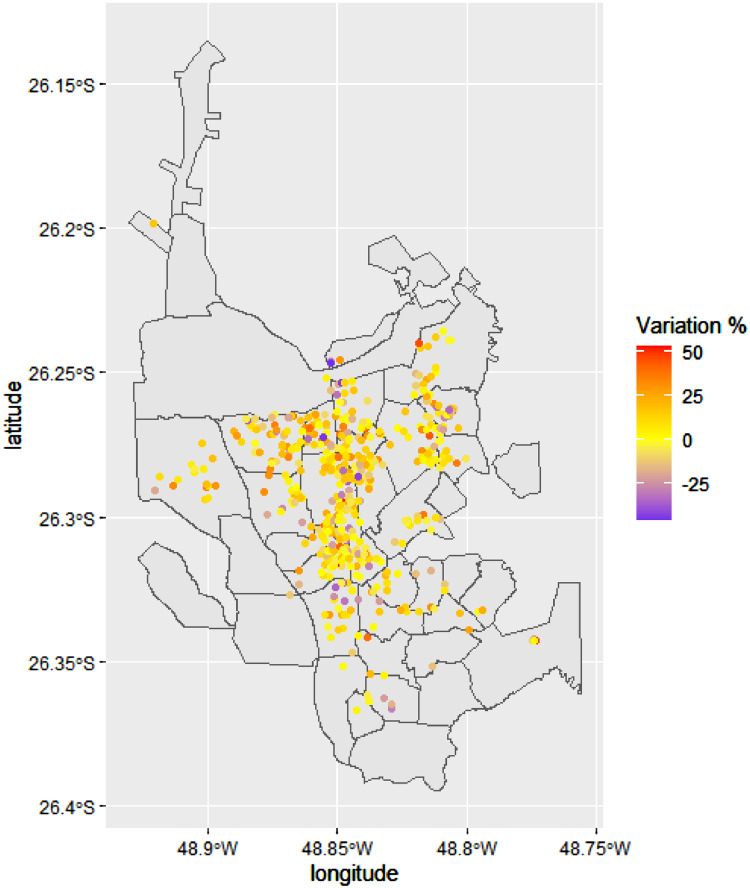

The spatial distribution of dwellings and the respective variations in water consumption can be seen on the map in Fig. 5 . The global Moran's I index indicates a positive and significant (p-value = 0.018) but weak (I = 0.016) association between the variation in water consumption and the spatial distribution of buildings.

Fig. 5.

Spatial distribution and variation of water consumption in households.

The residential water consumption category is divided into houses (n = 319), condominiums (n = 134), and apartment buildings (n = 395). In the case of condominiums and apartment buildings, consumer units missing information on the number of dwellings were excluded from this analysis. The descriptive statistics are presented in Table 4 divided by type of building. Water consumption data are presented in two periods, before and after the implementation of COVID-19 spread-prevention actions.

Table 4.

- Descriptive statistics of residential water consumption (m³/household/day) for each category.

| Category | Before | After |

|---|---|---|

| (Feb-21 Mar-17) | (Mar-18 Apr-12) | |

| Houses (n = 319) | ||

| Mean ± SD | 0.40377 ± 0.18026 | 0.40382 ± 0.18173 |

| Median | 0.39058 | 0.38081 |

| Interquartile Range | 0.26525 | 0.29573 |

| Condominiums (n = 134) | ||

| Mean ± SD | 0.33169 ± 0.13646 | 0.32880 ± 0.127695 |

| Median | 0.32927 | 0.33109 |

| Interquartile Range | 0.15399 | 0.16600 |

| Apartment buildings (n = 395) | ||

| Mean ± SD | 0.33998 ± 0.12132 | 0.33998 ± 0.12132 |

| Median | 0.31608 | 0.34765 |

| Interquartile Range | 0.14745 | 0.15080 |

*SD: Standard Deviation.

A Kruskal-Wallis H test was performed to explore the variation of water consumption per dwelling considering the different types of buildings (houses, condominiums and buildings). There is a statistically significant difference between categories (n = 848, χ 2 = 16.908, p-value = 0.0002). The results of the Bonferroni post hoc test show a significant difference between apartment buildings and condominiums (p-value = 0.014), and between apartment buildings and houses (p-value = 0.00034). The results indicate that the increase in water consumption was higher in apartment buildings when compared to houses, whether isolated or grouped in condominiums.

Brasche and Bischof (2005) found shorter home-staying periods for people living in the center of cities with more than 200,000 inhabitants and for occupants of small apartments. Sukarno et al. (2017) mention the possibility of occupations with longer working hours and social activities that reduce the period at home in more populated areas. Also, the mean time (in hours) spent daily at home is greater in single-family households when compared to multi-family buildings (Brasche and Bischof, 2005). Considering these studies and the analysis of water consumption after social isolation measures, the most significant increase in water consumption in apartment buildings may indicate that the time spent at home has increased more significantly in this type of building.

3.3. Discussion

Some studies found results suggesting that social isolation may be associated with containing the epidemic (Tian et al., 2020; Tobías, 2020). Assessing the impact of social isolation measures on urban water consumption is essential for the planning and management of water resources. According to Spencer et al. (2020), public health and the reduction of infectious diseases are important components of urban planning. The management of water resources during the COVID-19 pandemic is especially important because hygiene and cleaning habits (Pung et al., 2020; Sohrabi et al., 2020) need to be practiced by the population. Thus, aspects related to urban water consumption must be evaluated to ensure proper water supply, which is fundamental to limit the evolution of the pandemic.

The results conveyed a reduction in industrial, commercial and public water consumption, as well as an increase in residential water consumption. Regarding the pandemic control, the recommendation is to prioritize and guarantee the water supply to health services and other essential activities, such as activities directly or indirectly linked to the pandemic's spread prevention. Furthermore, the continuity of water supply to all residential consumers must be guaranteed, since essential hygiene practices can only be maintained by the population with proper water supply.

The fundamental access to safe water and sanitation systems for all communities, especially in crisis situations, must be enforced in the development of public policies. The human right to water and sanitation is based on the following normative criteria: availability, quality, safety, acceptability, accessibility and affordability (Albuquerque, 2010). As many cities face water supply crises, it is essential to plan water systems and act to increase resilience in situations of water stress.

4. Conclusions

The coronavirus (COVID-19) spread-prevention actions had a remarkable impact on urban water consumption, leading to a decrease in commercial, industrial and public usage, and a slight increase on residential consumption. The comparison between water consumption averages in the sample shows that it decreased by 53%, 42% and 30% in the industrial, commercial and public categories, respectively. The average water consumption in the sample increased by 11% in the residential category.

The results obtained for the Wilcoxon test show that there are differences in water consumption per category in the periods before and after the social-isolation measures. As for the regression models, the results showed a significant reduction in water consumption for commercial, industrial and public activities. However, the parameter that indicates the increase in water consumption in the residential category was not significative. When analyzing the differences in residential consumption by type of building, it was found that consumption variation was higher in apartment buildings.

The greatest reduction in water consumption was observed in industrial activities, followed by the commercial segment. The closure of schools, shopping malls, restaurants and hotels has reduced water consumption in those types of venues. A decrease in consumption observed in hospitals, due to specificities of location and time, is also noteworthy. The assessment of water consumption under crisis or pandemic situations is important for decision makers to define actions to ensure the availability of water for the population and for the maintenance of essential services. In the specific case of this study, hygiene and cleaning measures, essential to prevent the spread of COVID-19, are extremely important and depend on the availability of safe water.

Credit author statement

Andreza Kalbusch: Conceptualization; Formal analysis; Funding acquisition; Investigation; Methodology; Project administration; Supervision; Validation; Writing - original draft; Writing - review & editing.

Elisa Henning: Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Project administration; Software; Supervision; Validation; Writing - original draft; Writing - review & editing.

Miqueias Paulo Brikalski: Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Software; Validation; Writing - original draft; Writing - review & editing.

Felipe Vieira de Luca: Data curation; Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Validation; Writing - original draft; Writing - review & editing.

Andrea Cristina Konrath: Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Software; Supervision; Validation; Writing - original draft; Writing - review & editing.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Águas de Jonville for the water consumption database. This research was supported by Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico – CNPq (grant number 421062/2018–5) and Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa e Inovação do Estado de Santa Catarina – FAPESC (grant number 2019TR594).

References

- Albuquerque C. Independent Expert on the Issue of Human Rights Obligations Related to Access to Safe Drinking Water and Sanitation; 2010. UN Human Rights Council.https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/685823#record-files-collapse-header accessed 23 April 2020. [Google Scholar]

- André D.M., Carvalho J.R. Spatial determinants of urban residential water demand in fortaleza, Brazil. Water Resour. Manage. 2014;28:2401–2414. doi: 10.1007/s11269-014-0551-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Andrés M., Barragán J.M., Scherer M. Urban centres and coastal zone definition: which area should we manage? Land use policy. 2018;71:121–128. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2017.11.038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bence J.R. Analysis of short time series: correcting for autocorrelation. Ecology. 1995;76:628–639. doi: 10.2307/1941218. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bivand R., Wong D.W.S. Comparing implementations of global and local indicators of spatial association. TEST. 2018;27(3):716–748. doi: 10.1007/s11749-018-0599-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Booysen M.J., Visser M., Burger R. Temporal case study of household behavioural response to Cape Town's “Day Zero” using smart meter data. Water Res. 2019;149:414–420. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2018.11.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brasche S., Bischof W. Daily time spent indoors in German homes – Baseline data for the assessment of indoor exposure of German occupants. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health. 2005;208:247–253. doi: 10.1016/j.ijheh.2005.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brauer, M.; Zhao, J.T.; Bennitt, F.B.; Stanaway, J.D.;.2020. Global access to handwashing: implications for COVID-19 controling low-income countries. 10.1101/2020.04.07.20057117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Cortegiani A., Ingoglia G., Ippolito M., Giarratano A., Einav S... A systematic review on the efficacy and safety of chloroquine for the treatment of COVID-19. J. Criti. Care. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2020.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cureau R.J., Ghisi E. Electricity savings by reducing water consumption in a whole city: a case study in Joinville, Southern Brazil. J. Clean. Prod. 2020:261. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.121194. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Deyà-Tortella, B.; Garcia, C.; Nilsson, W.; Tirado, D., 2017. Analysis of water tariff reform on water consumption in different housing typologies in Calvià (Mallorca). 9, 425. 10.3390/w9060425. [DOI]

- Ghasemi A., Zahediasl S. Normality tests for statistical analysis: a guide for non-statisticians. Int. J. Endocrinol. Metab. 2012;10:486–489. doi: 10.5812/ijem.3505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang N.E., Qiao F. A data driven time-dependent transmission rate for tracking an epidemic: a case study of 2019-nCoV. Sci. Bull. 2020;65:425–427. doi: 10.1016/j.scib.2020.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyndman R.J., Athanasopoulos G. 2nd edition. OTexts; Melbourne, Australia: 2018. Forecasting: Principles and Practice. OTexts.com/fpp2 (accessed 13 April 2020) [Google Scholar]

- Hyndman R.J., Khandakar Y. Automatic time series forecasting: the forecast package for R. J. Statist. Softw. 2008;26:1–22. doi: 10.18637/jss.v027.i03. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- IBGE- Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatistica. Censo Demográfico2010. https://cidades.ibge.gov.br/brasil/sc/joinville/panorama (accessed 13 April 2020).

- Joinville, 2020. PORTARIA Nº 36/2020/SMS. https://sei.joinville.sc.gov.br/sei/publicacoes/controlador_publicacoes.php?acao=publicacao_visualizar&id_documento=10000006483651&id_orgao_publicacao=0 (accessed 15 April 2020).

- Kottek M., Grieser J..., Beck C., Rudolf B., Rubel F. World map of the Köppen-Geiger climate classification updated. Meteorol. Z. 2006;15:259–263. doi: 10.1127/0941-2948/2006/0130. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lau J.T.F., Griffiths S., Choi K.C., Tsui H.Y. Widespread public misconception in the early phase of the H1N1 influenza epidemic. J. Infect. 2009;59:122–127. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2009.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee A. Wuhan novel coronavirus (COVID-19): why global control is challenging? Public Health. 2020:179. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2020.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohr F.X. Prais: prais-Winsten estimator for AR(1) serial correlation. R Package version. 2019 https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=prais 1.1.1. accessed 02 April 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ollech, D., 2019. Seastests: seasonality tests. R package version 0.14.2. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=seastests (accessed 02 April 2020).

- Pebesma E. Simple features for R: standardized support for spatial vector data. R J. 2018;10(1):439–446. doi: 10.32614/RJ-2018-009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pohlert T. The pairwise multiple comparison of mean ranks package (PMCMR) R Packag. 2014 https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=PMCMR accessed 02 May 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Pung R., Chiew C.J., Young B.E., Chin S., Chen M.I., Clapham H.E. Investigation of three clusters of COVID-19 in Singapore: implications for surveillance and response measures. Lancet North Am. Ed. 2020;395:1039–1046. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30528-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team . R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria; 2020. R: a language and environment for statistical computing.https://www.R-project.org/ Available at. accessed 10 April 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Roy D., Tripathy S., Kar S.K., Sharma N., Verma S.K., Kaushal V. Study of knowledge, attitude, anxiety & perceived mental healthcare need in Indian population during COVID-19 pandemic. Asian J. Psychiatry. 2020;51 doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santa Catarina, 2020. Decreto Nº 515 DE 17/03/2020. Declara situação de emergência em todo o território catarinense, nos termos do COBRADE n° 1.5.1.1.0 - doenças infecciosas virais, para fins de prevenção e enfrentamento à COVID-19, e estabelece outras providências. https://www.sc.gov.br/images/Secom_Noticias/Documentos/VERS%C3%83O_ASSINADA.pdf (accessed 15 April 2020).

- Sarkis J., Cohen M.J., Dewick P., Schröder P. A brave new world: lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic for transitioning to sustainable supply and production. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020;159 doi: 10.1016/j.resconrec.2020.104894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singhal T. A review of coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) Indian J. Pediatr. 2020;87:281–286. doi: 10.1007/s12098-020-03263-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohrabi C., Alsafi Z., O'Neill N., Khan M., Kerwan A., Al-Jabir A., Iosifidis C., Agha R. World health organization declares global emergency: a review of the 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19) Int. J. Surg. 2020;76:71–76. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.02.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorenson S.B., Morssink C., Campos P.A. Safe access to safe water in low income countries: water fetching in current times. Soc. Sci. Med. 2011;72:1522–1526. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer J.H., Finucane M.L., Fox J.M., Saksena S., Sultana N. Emerging infectious disease, the household built environment characteristics and urban planning: evidence on avian influenza in Vietnam. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2020;193 doi: 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2019.103681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sukarno I., Matsumoto H., Susanti L. Household lifestyle effect on residential electrical energy consumption in Indonesia: on-site measurement methods. Urban Climate. 2017;20:20–32. doi: 10.1016/j.uclim.2017.02.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tennekes M. Tmap: thematic Maps in R. J. Stat. Softw. 2018;84(6):1–39. doi: 10.18637/jss.v084.i06. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tian H., Liu Y., Li Y., Wu C., Chen B., Kraemer M.U.G. . An investigation of transmission control measures during the first 50 days of the COVID-19 epidemic in China. Science. 2020 doi: 10.1126/science.abb6105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian F., Lu Y., Hu H., Kinzelbach W., Sivapalan M. Dynamics and driving mechanisms of asymmetric human water consumption during alternating wet and dry periods. Hydrol. Sci. J. 2019;64:507–524. doi: 10.1080/02626667.2019.1588972. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tobías A. Evaluation of the lockdowns for the SARS-CoV-2 epidemic in Italy and Spain after one month follow up. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;725 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vargas L., Mingoti S.A., Heller L. Impact of a Programme for Water Affordability on Residential Consumption: implementation of the “Programa Mínimo Vital de Agua Potable” in Bogotá, Colombia. Water (Basel) 2018;10:158. doi: 10.3390/w10020158. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q., Wang X. Sci. Total Environ. 2020. Is economic growth decoupling from water use? Empirical analysis of 31 Chinese provinces. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wei Y., Wang Z., Wang H., Yao T., Li Y. Promoting inclusive water governance and forecasting the structure of water consumption based on compositional data: a case study of Beijing. Sci. Total Environ. 2018;634:407–416. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.03.325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickham H. Springer-Verlag; New York: 2016. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics For Data Analysis. [Google Scholar]

- Wilcoxon F. Individual Comparisons by Ranking Methods. In: Kotz S., Johnson N.L., editors. Breakthroughs in Statistics. Springer Series in Statistics (Perspectives in Statistics. Springer; New York, NY: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- WHO - World Health Organization, 2015. Water sanitation and hygiene (WASH) package and WASH safety plans Training of trainers. https://www.who.int/csr/disease/ebola/wash-training.pdf?ua=1>(accessed 02 April 2020).

- Zhong B.L., Luo W., Li H.M., Zhang Q.Q., Liu X.G., Li W.T., Li Y. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices towards COVID-19 among Chinese residents during the rapid rise period of the COVID-19 outbreak: a quick online cross-sectional survey. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2020;16:1745–1752. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.45221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou S.L., McMahon T.A., Walton A., Lewis J. Forecasting operational demand for an urban water supply zone. J. Hydrol. 2002;259:189–202. doi: 10.1016/S0022-1694(01)00582-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]