Abstract

Aim

To investigate the specific risk factors for novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) transmission among health care workers (HCWs) in a tertiary care university hospital.

Methods

Upper respiratory samples of HCWs were tested for SARS-CoV-2 by reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction. A case-control study was conducted to explore the possible risk factors that lead to SARS-CoV-2 transmission to HCWs.

Results

Of 703 HCWs screened between March 20 and May 20, 2020, 50 (7.1%) were found to be positive for SARS-CoV-2. The positivity rates for SARS-CoV-2 among physicians, nurses, cleaning personnel, and the other occupations were 6.3%, 8.0%, 9.1%, and 2.6%, respectively. The infection rate was 8.3% among HCWs who worked in COVID-19 units and 3.4% among those who did not work in coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) units (RR = 2.449, confidence interval = 1.062-5.649, P= .027). The presence of a SARS-CoV-2 positive person in the household (P = .016), inappropriate use of personnel protective equipment while caring for patients with COVID-19 infection (P = .003), staying in the same personnel break room as an HCW without a medical mask for more than 15 minutes (P = .000), consuming food within 1 m of an HCW (P = .003), and failure to keep a safe social distance from an HCW (P = .003) were statistically significant risk factors for infection.

Conclusion

HCWs have a high risk for SARS-CoV-2 transmission while providing care to COVID-19 patients. Transmission may also occur in nonmedical areas of the hospital while speaking or eating. Periodic screening of HCWs for SARS-CoV-2 may enable early detection and isolation of infected HCWs.

Key Words: Health care worker, COVID-19, Case-control, Infection control

INTRODUCTION

The novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2), the causative agent of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), has become the most severe public health emergency worldwide.1 The disease, which emerged in Wuhan, China in December 2019, rapidly spread internationally and was declared a pandemic by the World Health Organization on March 11, 2020.2 SARS-CoV-2 has infected over 4,500,000 people and caused over 300,000 deaths worldwide.1 Current data suggest that, in community settings, person-to-person transmission most commonly occurs via the respiratory droplets of the infected person (during coughing, sneezing, speaking, etc.), close contact with the infected person, or self-delivery of the virus to the eyes, nose, or mouth via contaminated hands after contact with SARS-CoV-2-contaminated surfaces.3 In health care settings, in addition to respiratory droplet-borne or contact-borne transmission, airborne transmission can also occur during aerosol-generating implementations.

The SARS-CoV-2 is highly contagious, and health care workers (HCWs) have been working with a significant risk of virus transmission while providing care to suspected or confirmed COVID-19 patients. Several reports have indicated that many HCWs have been infected with SARS-CoV-2 in many hospitals worldwide.4, 5, 6, 7, 8 The World Health Organization and other national and international public health authorities have published guidelines for handling COVID-19, which recommend implementing safety protocols for HCWs such as using appropriate personnel protective equipment (PPE).9 , 10 However, as the recommended infection control precautions have not been adequate enough to prevent the spread of the SARS-CoV-2 infection among HCWs, unrecognized risk factors may contribute to the virus transmission in hospitals.

This study investigates the specific risk factors for the SARS-CoV-2 transmission among HCWs in a university hospital and makes suggestions for improving occupational safety during the COVID-19 outbreak.

Material and methods

Hospital settings

Zonguldak Bülent Ecevit University Hospital is a teaching and tertiary care hospital with 630 inpatient beds, which includes 82 intensive care unit beds (adult: 50, newborn: 25, and pediatric: 7). The first laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 case in Turkey was announced by the Turkish Ministry of Health (MoH) on March 11, 2020. One week after the first recorded case in the country, the first laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 case in Zonguldak Province was detected on March 18, and the first case in our hospital was confirmed on March 20. Appendix 1 summarizes the main organization and preparedness plans for the COVID-19 pandemic in our hospital.

The first HCW infected with SARS-CoV-2 at our hospital was detected on March 26, 2020 (6 days after the first confirmed case of a COVID-19 admission). The HCW was a medical doctor (resident in the Anesthesiology and Reanimation Department) and had not worked in a COVID-19 unit before being infected. As the parents of the resident also tested positive for SARS-CoV-2, we could not identify whether SARS-CoV-2 transmission was hospital-acquired or household-acquired. The number of infected HCWs reached 5 on the 10th day and 11 on the 15th day after notification of the first laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 case in the hospital. However, only 2 of the infected HCWs had worked in a COVID-19 unit before becoming infected. Furthermore, there were clusters of 4 and 3 cases of infected HCWs in 2 non-COVID-19 units.

Case-control study

A routine survey to identify the mode of transmission and possible risk factors that contribute to SARS-CoV-2 transmission to HCWs in the hospital was performed by the Infection Control Committee. A 33-item questionnaire (supplementary document in Appendix 2), including possible exposure modes to SARS-CoV-2 in the hospital, was prepared, and interviews with the voluntary HCWs were conducted face-to-face (35 HCWs) or via telephone (150 HCWs) by the infection control nurses and the infection disease fellow. The HCWs who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 by real-time reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) were recorded as the case group and those who tested negative for SARS-CoV-2, had no symptoms compatible with COVID-19 infection and had stayed asymptomatic for 14 days following the RT-PCR test formed the control group. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (2008). Written approval was obtained from the Hospital Administration, and the study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Medical Faculty at Zonguldak Bülent Ecevit University (approval number: 2020/10) in Zonguldak.

RT-PCR detection

HCWs who had symptoms compatible with the COVID-19 infection or who were in close contact with a person infected with SARS-CoV-2 were admitted to the COVID-19 policlinic in the hospital. Combined samples from the oropharynx and nasopharynx via flocked swabs were obtained from the HCWs and sent to the microbiology laboratory of our hospital in a viral transport medium (Bioeksen, Turkey). The presence of SARS-CoV-2 in specimens was detected by RT-PCR amplification of SARS-CoV-2 RdRp-gene using Bio-Speedy-2 Version 1 and 2 RT-qPCR kits (Bioeksen, Turkey). The limit of detection reported by the MoH’s General Directorate of Public Health was 5.6 copies/reaction, and analytical sensitivity and specificity of 99.4% and 99.0%, respectively. RT-qPCR was performed using Rotor-Gene 5r Plex RT-PCR Systems (Qiagen, Germany). A cycle threshold value (Ct-value) less than 38 was defined as a positive test result, and a Ct-value of 38 or more was defined as a negative test result.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics of the categorical variables are given as numbers or percentages, and continuous variables are given as medians (min-max). The chi-square test or Fisher's exact test was used to evaluate the categorical variables. Binary logistic regression analysis was performed using stepwise backward selection to identify independent predictors associated with SARS-CoV-2 positivity in HCWs. All variables with a Pvalue <.20 in the initial analysis were included in the multivariate analysis. The associations are presented as odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). A statistical analysis was performed using SPSS Version 18.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). All Pvalues were 2-sided, and values less than .05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

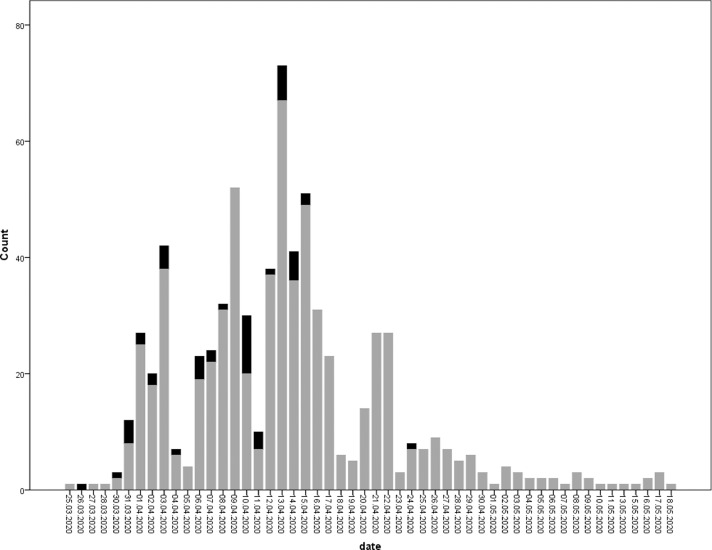

During a 60-day period (March 20-May 20), 703 HCWs were admitted to the COVID-19 policlinic, and 50 (7.1%) were found to be positive for SARS-CoV-2 by RT-PCR (Fig 1 ). Among the 50 HCWs, 7 were medical doctors (6 residents and 1 faculty member), 28 were nurses, 12 were cleaning personnel (environmental service workers), 2 were laboratory technicians, and 1 was nutrition service worker. The mean age of the infected HCWs was 35.5 (min-max = 21-61, SD = 7.57); 33 were female (66%) and 17 were male (34%). The positivity rates for SARS-CoV-2 among the physicians, nurses, cleaning personnel, and other occupations were 6.3%, 8.0%, 9.1%, and 2.6%, respectively (Table 1 ). Of the HCWs, 546 had a single RT-PCR test and the remaining 157 had 2-5 tests.

Fig 1.

The number of HCWs who tested for SARS-CoV-2 by RT-PCR on the timeline. The black bars indicate the HCWs who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 and the grey bars indicate the HCWs who tested negative for SARS-CoV-2.

Table 1.

The positivity rates for SARS-CoV-2 among physicians, nurses, cleaning personnel, and other occupations

| Profession | RT-PCR positive n/N (%) | RT-PCR negative n/N (%) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Medical doctor | 8/128 (6.3%) | 120/128 (93.8%) | .094 |

| Nurse | 22/274 (8%) | 252/274 (92%) | |

| Cleaning personnel | 17/186 (9.1%) | 169/186 (90.9%) | |

| Other | 3/115 (2.6%) | 112/115 (97.4%) | |

| Total | 50/703 (7.1%) | 653/703 (92.9%) |

Among the HCWs who were screened for SARS-CoV-2 by RT-PCR, 8.3% worked in the COVID-19 units and 3.4% did not work in the COVID-19 units, indicating a statistically significant difference (RR = 2.449, CI = 1.062-5.649, P= .027). In the subgroup analyses, the positivity rates were higher among the nurses, the environmental service workers, and other professions who worked in the COVID units compared to those who did not. However, the differences were not statistically significant (Table 2 ).

Table 2.

RT-PCR positivity rates among the HCWs who worked in COVID-19 units and those who did not

| Work location | RT-PCR positive n/N (%) | RT-PCR negative n/N (%) | Relative risk (RR) |

|---|---|---|---|

| HCWs worked in a COVID-19 unit | 44/527 (8.3%) | 483/527 (91.7%) | RR = 2.449 (CI = 1.062-5.649) P = .027 |

| HCWs did not work in a COVID-19 unit | 6/176 (3.4%) | 170/176 (96.6%) | |

| Medical doctor worked in a COVID-19 unit | 5/114 (4.4%) | 109/114 (95.6%) | RR = 0.205 (CI = 0.055-0.766) P = .042 |

| Medical doctor did not work in a COVID-19 unit | 3/14 (21.4%) | 11/14 (78.6%) | |

| Nurses worked in a COVID-19 unit | 19/187 (10.2%) | 168/187 (89.8%) | RR = 2.947 (CI = 0.896-9.693) P = .057 |

| Nurses did not work in a COVID-19 unit | 3/87 (3.4%) | 84/87 (96.6%) | |

| Cleaning personnel worked in a COVID-19 unit | 17/167 (10.2%) | 150/167 (89.8%) | RR = 2.237 (CI = 0.314-15.910) P = .700 |

| Cleaning personnel did not work in a COVID-19 unit | 0/19 (0.0%) | 19/19 (100%) | |

| Other worked in a COVID-19 unit | 3/59 (5.1%) | 56/59 (94.9%) | RR = 3.803 (CI = 0.438-33.032) P = .365 |

| Other did not work in a COVID-19 unit | 0/56 (0.0%) | 56/56 (100.0%) |

Case-control study

Since the possible risk factors for SARS-CoV-2 transmission were dissimilar, laboratory personnel and nutrition service personnel were excluded, and statistical analyses were performed for 47 cases and 134 controls. Table 3 shows a comparison of the cases and the controls according to their basic characteristics and the possible exposure modes to SARS-CoV-2. In the univariate analyses, the presence of a SARS-CoV-2 positive individual in the household (P = .016), inappropriate use of PPE during the care of suspected or confirmed cases of COVID-19 (P = .003), staying in the same personnel break room as an HCW without a medical mask for more than 15 minutes (P = .000), consuming food within 1 m of other HCWs (P = .003), and failing to keep a safe social distance from an HCW (P = .003) were higher in the case group than in the controls, with statistically significant differences (Table 3).

Table 3.

Basic characteristics of the cases and the controls

| Variables | Cases N = 47 | Controls N = 134 | P* value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Date interval of RT-PCR detection | 26.03.2020-16.04.2020 | 26.03.2020-30.04.2020 | |

| Age (the mean, min-max) | 35.7 (21-61) | 34.4 (21-50) | .253 |

| n/(%) | n/(%) | ||

| Sex | .507 | ||

| Female | 32 (68.1) | 84 (62.7) | |

| Male | 15 (31.9) | 50 (37.3) | |

| Profession | .107 | ||

| Medical doctor | 7 (14.9) | 41 (30.6) | |

| Nurse | 28 (59.6) | 67 (50.0) | |

| Cleaning personnel | 12 (25.5) | 26 (19.4) | |

| Having an underlying disorder | 16 (34.0) | 41 (30.6) | .662 |

| Presence of an HCW in the household | 10 (21.3) | 31 (23.1) | .793 |

| Presence of a SARS-CoV-2 positive person in the household | 3 (6.5) | 0 (0.0) | .016 |

| Presence of a SARS-CoV-2 positive person within the occupational or social surroundings | 25 (53.2) | 109 (81.3) | .000 |

| Working in a COVID-19 unit (yes) | 31 (66.0) | 99 (73.9) | .299 |

| Entering a room in which a suspected or confirmed COVID-19 patient was hospitalized (yes) | 31 (66.0) | 103 (76.9) | .142 |

| Examining (touching) a suspected or confirmed Covid-19 patient (yes) | 27 (57.4) | 102 (76.1) | .015 |

| Obtaining a respiratory sample from a suspected or confirmed COVID-19 patient (yes) | 9 (19.1) | 43 (32.1) | .092 |

| Intubating a suspected or confirmed COVID-19 patient or being present in the room during intubation (yes) | 6 (13.3) | 21 (15.7) | .705 |

| Resuscitating a suspected or confirmed COVID-19 patient or being present in the room during resuscitation (yes) | 6 (13.0) | 14 (10.4) | .629 |

| Entering the ICU room of a suspected or confirmed patient with mechanical ventilation (yes) | 9 (19.6) | 33 (24.6) | .484 |

| Being present in the operation room during a surgical procedure on a suspected or confirmed COVID-19 patient (yes) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.5) | 1.000 |

| Improper use of PPE while caring for a suspected or confirmed COVID-19 patient | 8 (17.0 ) | 5 (3.8 ) | .003 |

| Making a mistake while implementing infection control precautions (yes) | 3 (6.4) | 3 (2.3) | .191 |

| Staying in the same personnel break room as an HCW without wearing medical mask for more than 15 minutes (yes) | 33 (70.2) | 37 (27.8) | .000 |

| Consuming food within one meter of an HCW (yes) | 33 (70.2) | 60 (44.8) | .003 |

| Failing to keep a safe social distance from an HCW | 29 (63.0) | 52 (39.1) | .005 |

A student t test was used to compare the groups; a P value indicates the degree of statistical significance.

When the groups were compared using binary logistic regression analyses, inappropriate use of PPE during the care of suspected or confirmed cases of COVID-19 (OR = 11.295, CI = 2.183-59.429, P = .04) and staying in the same personnel break room as other HCWs without wearing a medical mask for more than 15 minutes (OR = 7.422, CI = 1.898-29.020, P = .04) were found to be statistically significant risk factors for SARS-CoV-2 transmission to HCWs.

In subgroup analyses, staying in the same room and consuming food were not statistically significant risk factors for medical doctors, but they were for the nurses and the environmental service workers.

Among the 50 RT-PCR positive HCWs, 14 were asymptomatic, 36 were symptomatic, and 7 were treated as inpatients. No deaths or intensive care unit requirements occurred.

Discussion

The pandemic SARS-CoV-2 is a highly contagious agent, and many HCWs have become infected while providing care to COVID-19 patients in many hospitals worldwide.4, 5, 6, 7 In a publication released by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 19% of the 49,370 COVID-19 patients reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention between February 12 and April 9, 2020 were HCWs, the majority of whom claimed that their exposure occurred in healthcare settings.11 Among 25,961 laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 patients from Wuhan, China, HCWs accounted for 5.1% of the patients.5 Additionally, according to the data collected from 30 countries by the International Council of Nurses, an average of 6% (range between 0% and 18%) of the confirmed COVID-19 cases were HCWs.12 A recent report from the Turkish Medical Association indicated that nearly 6% of the laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 cases were HCWs, based on the public declaration of the Turkish MoH on April 29.13 Further, the authors of a survey conducted on March 6-8, 2020 in the Netherlands screened 1,067 HCWs from 9 hospitals for SARS-CoV-2 by RT-PCR; 4.1% of the HCWs tested positive and the positivity rate between the hospitals varied between 0% and 9.5%.6 In our hospital, of the 703 HCWs—nearly 45% of the total number of HCWs working in the hospital—tested by RT-PCR, 7.1% were found to be positive for SARS-CoV-2. The SARS-CoV-2 infection rates among the physicians, nurses, cleaning personnel, and the other occupations were 6.3%, 8.0%, 9.1%, and 2.6%, respectively.

A few published studies have investigated the possible risk factors for SARS-CoV-2 in HCWs. In a study in China, 72 physicians and nurses with acute respiratory illness were retrospectively enrolled to investigate the risk factors. Working in a high-risk department, suboptimal handwashing before or after patient contact, longer working hours, and improper use of PPE were found to be risk factors for SARS-CoV-2 transmission between HCWs.14 In our hospital, we began preparing for the COVID-19 pandemic several days before the first case was detected in Turkey (Appendix 1). The most important part of the preparedness was providing personnel training before assigning HCWs to the COVID-19 units to ensure proper PPE use and to enforce the use of basic infection control precautions among all HCWs when entering and leaving patient rooms. Nevertheless, within the first 15 days of the pandemic in the hospital, 11 HCWs were infected with SARS-CoV-2. The initial observational findings indicated that the clusters of infected HCWs were unrelated to COVID-19 patients or units and were mostly related to nonmedical activities in non-COVID-19 units. In a non-COVID inpatient clinic, four HCWs (1 physician, 2 nurses, and 1 cleaning staff) were concurrently infected with SARS-CoV-2, and the most salient risk factor was having lunch in the same personnel break room at the same time. Furthermore, in another non-COVID unit, a cluster of 3 infected HCWs defined similar activities as possible risk factors for the transmission of SARS-CoV-2. The Infection Control Committee immediately declared the following additional recommendations for HCWs to prevent SARS-CoV-2 transmission:

-

1.

Mandatory and continuous use of medical masks by HCWs in all areas (including administrative offices, technical services, cafeterias, and break rooms) of the hospital.

-

2.

Forbidden consumption of food in all personnel break rooms.

-

3.

Forbidden sitting face-to-face while dining at the central cafeteria of the hospital.

-

4.

Informing and re-training all HCWs of the additional recommendations.

In addition, in two COVID-19 inpatient clinics, the nurses break rooms had no windows for fresh air ventilation; thus, new break rooms with windows were provided for the nurses in those clinics.

Following the implementation of the additional infection control precautions, the number of infected HCWs decreased, and only 1 HCW became infected after April 15, 2020 (Fig 1). In the case-control study, univariate analyses showed that the presence of a SARS-CoV-2 positive individual in the household (P = .016), inappropriate use of PPE while caring for patients with suspected or confirmed cases of COVID-19 (P = .003), staying in the same personnel break room as an HCW without wearing a medical mask for more than 15 minutes (P = .000), consuming food within 1 m of another HCW (P = .003), and failing to keep a safe social distance from an HCW (P = .003) were found to be statistically significant risk factors for the transmission of SARS-CoV-2. Logistic regression analyses supported that inappropriate use of PPE (OR = 11.295, CI = 2.183-59.429, P = .04) and staying in the same personnel break room as an HCW without a medical mask (OR = 7.422, CI = 1.898-29.020, P = .04) were statistically significant risk factors for the transmission of SARS-CoV-2 to HCWs. To our knowledge, this is the first published report demonstrating that staying in the personnel break room without wearing a medical mask for more than 15 minutes, concurrent food consumption in the hospital at a distance of less than 1 m and failure to adhere to social distancing rules were statistically significant risk factors for the transmission of SARS-CoV-2 among HCWs in hospital settings.

For HCWs, exposure to SARS-CoV-2 may be hospital-acquired, household-acquired, or community-acquired.11 The first HCW in our hospital that was infected with SARS-Co-V-2 had no exposure in the hospital but had been exposed to the virus in the household. Among the 50 infected HCWs in our hospital, 6.5% had household contact with infected individuals and 53.2% had contact with infected individuals in occupational or social surroundings. Therefore, it has not yet been possible to determine whether the proportion of HCWs infected with SARS-CoV-2 in our hospital was hospital-acquired or community-acquired. Further, seroprevalence studies both in the HCWs and in the community may provide results that are more informative. However, HCWs have a naturally high risk for SARS-CoV-2 infection due to occupational exposures that may occur several times within healthcare settings. In the current study, the positivity rates for SARS-CoV-2 among the HCWs who worked in frontline positions were higher (RR = 2.449, CI = 1.062-5.649, P = .027) than those who were not in frontline positions.

While individuals infected with SARS-CoV-2 mostly spread the virus during the symptomatic period, transmission may also occur within the asymptomatic or presymptomatic stages of the disease.15 Considering this situation is one of the key points in the success of preventing and controlling the transmission of the virus. In the current case series, 28% of the HCWs had no symptoms at admission for RT-PCR testing. The early detection and isolation of those HCWs has prevented SARS-CoV-2 transmission from those HCWs to other HCWs, patients, and the community. Therefore, periodic screening of the HCWs, even when asymptomatic and especially among those who are at high risk for SARS-CoV-2 transmission, may enable early detection and isolation of the HCWs.

This study has some limitations. First, the RT-PCR test is not an optimal method for detecting SARS-CoV-2 among HCWs. According to many publications, the sensitivity of SARS-CoV-2 detection by RT-PCR in nasal swap samples was reported to be an average of 70%.16 , 17 In SARS-CoV-2 infection in humans, IgM and IgG antibodies begin to rise at the early stage of the disease (initial 5-7 days after incubation) and reach their highest levels within two or three weeks.18 The seroconversion rates of IgM and IgG antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 at the late stage of the diseases were reported to be over 90% in recent publications.19 , 20 Therefore, a seroprevalence study could provide more accurate information on the infection rates of SARS-CoV-2 among HCWs in our hospital. However, convenient serodiagnostic test kits were not traditionally available in Turkey, while the current study was underway. Second, we did not question all possible modes of exposure to SARS-CoV-2 in the hospital. We questioned the possible risk factors of exposure categorically, but we failed to investigate the frequency, intensity, and duration of exposure for each HCW. Third, the data obtained in the case-control study may be partially subjective since the interviews rely heavily on participants’ self-reports. However, the initial observational findings of the infection control nurses, the results of the case-control study, and the personal experience and statements of the infected HCWs about the possible mode of transmission of the SARS-CoV-2 infection in the hospital were all in concordance in the current study.

CONCLUSION

HCWs face a high risk of SARS-CoV-2 transmission while providing care for suspected or confirmed COVID-19 patients. However, transmission may also occur in non-medical areas while speaking or eating in the hospital. The proper use of PPE and the implementation of basic infection control precautions are essential. Periodic screening of HCWs for SARS-CoV-2 may enable early detection and isolation of infected HCWs.

Acknowledgments

We thank to the voluntary HCWs for their interview, since they have provided the main data of this study, to the members of the Pandemic Control Committee for their intellectual contribution, and of course, to all the HCWs for their great combat against to COVID-19 infection in our hospital.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: None to report.

Contribution of the authors: All listed authors have made significant contributions to this article.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found in the online version at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajic.2020.07.039.

Appendix. SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

References

- 1.WHO timeline - COVID-19. Available at:https://www.who.int/news-room/detail/27-04-2020-who-timeline—covid-19. Accessed August 19, 2020.

- 2.Coronavirus disease (COVID-2019) situation reports. Available at:https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/situation-reports. Accessed August 19, 2020.

- 3.Interim U.S. guidance for risk assessment and work restrictions for healthcare personnel with potential exposure to COVID-19. Available at:https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/guidance-risk-assesment-hcp.html. Accessed August 19, 2020.

- 4.Xiang YT, Jin Y, Wang Y, Zhang Q, Zhang L, Cheung T. Tribute to health workers in China: a group of respectable population during the outbreak of the COVID-19. Int J Biol Sci. 2020;16:1739–1740. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.45135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chou R, Dana T, Buckley DI, Selph S, Fu R, Totten AM. Epidemiology of and risk factors for coronavirus infection in health care workers. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173:120–136. doi: 10.7326/M20-1632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reusken CB, Buiting A, Bleeker-Rovers C, et al. Rapid assessment of regional SARS-CoV-2 community transmission through a convenience sample of healthcare workers, the Netherlands, March 2020. Euro Surveill. 2020;25 doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.12.2000334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heinzerling A, Stuckey MJ, Scheuer T, et al. Transmission of COVID-19 to health care personnel during exposures to a hospitalized patient - solano county, california, february 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:472–476. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6915e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Keeley AJ, Evans C, Colton H, et al. Roll-out of SARS-CoV-2 testing for healthcare workers at a large NHS foundation trust in the United Kingdom, march 2020. Euro Surveill. 2020;25 doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.14.2000433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lynch JB, Davitkov P, Anderson DJ, et al. Infectious diseases society of America guidelines on infection prevention in patients with suspected or known COVID-19 published by IDSA, 4/27/2020. Available at: https://www.idsociety.org/COVID19guidelines/ip. Accessed August 19, 2020.

- 10.Infection prevention and control during health care when novel coronavirus (nCoV) infection is suspected. 2020. Available at:https://www.who.int/publications-detail/infection-prevention-and-control-during-health-care-when-novel-coronavirus-(ncov)-infection-is-suspected-20200125. Accessed August 19, 2020.

- 11.CDC COVID-19 Response Team Characteristics of health care personnel with COVID-19 — United States, february 12–April 9, 2020. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:477–481. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6915e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.ICN calls for data on healthcare worker infections and deaths. Available at:https://www.2020yearofthenurse.org/story/icn-calls-for-data-on-healthcare-worker-infection-rates-deaths/. Accessed August 19, 2020

- 13.Assessment Report for COVID-19. Turkish medical association. Available at:https://www.ttb.org.tr/userfiles/files/covid19-rapor.pdf. Accessed August 19, 2020

- 14.Ran L, Chen X, Wang Y, Wu W, Zhang L, Tan X. Risk factors of healthcare workers with corona virus disease 2019: a retrospective cohort study in a designated hospital of Wuhan in China [e-pub ahead of print]. Clin Infect Dis. 10.1093/cid/ciaa287. Accessed August 19, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Rivett L, Sridhar S, Sparkes D, et al. Screening of healthcare workers for SARS-CoV-2 highlights the role of asymptomatic carriage in COVID-19 transmission. Elife. 2020;9:e58728. doi: 10.7554/eLife.58728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li X, Geng M, Peng Y, Meng L, Lu S. Molecular immune pathogenesis and diagnosis of COVID-19. Version 2. J Pharm Anal. 2020;10:102–108. doi: 10.1016/j.jpha.2020.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bohn MK, Lippi G, Horvath A, et al. Molecular, serological, and biochemical diagnosis and monitoring of COVID-19: IFCC taskforce evaluation of the latest evidence. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2020;58:1037–1052. doi: 10.1515/cclm-2020-0722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Long QX, Liu BZ, Deng HJ, et al. Antibody responses to SARS-CoV-2 in patients with COVID-19. Nat Med. 2020:845–848. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0897-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xiang F, Wang X, He X, et al. Antibody detection and dynamic characteristics in patients with COVID-19 [e-pub ahead of print]. Clin Infect Dis. 10.1093/cid/ciaa461. Accessed August 19, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Lou B, Li TD, Zheng SF, et al. Serology characteristics of SARS-CoV-2 infection since exposure and post symptom onset. Eur Respir J. 2020;56:2000763. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00763-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.