Abstract

The quality of life associated with eating is becoming an increasingly significant problem for patients who undergo esophagectomy as a result of the improved survival rate after esophageal cancer surgery. Delayed gastric emptying (DGE) is a common complication after esophagectomy. Although several strategies have been proposed for the management and prevention of DGE, no clear consensus exists. The purpose of this review is to present a brief overview of DGE and to help clinicians choose the most appropriate treatment through an analysis of DGE by cause. Furthermore, we would like to suggest some tips to prevent DGE based on our experience.

Keywords: Esophageal neoplasms, Esophagectomy, Gastric emptying, Pyloric intervention, Mediastinum

Introduction

The survival rate after esophageal cancer surgery has improved as a result of early cancer detection and advances in adjuvant therapy [1]. However, impaired quality of life (QOL) associated with eating remains a significant problem [2,3]. Delayed gastric emptying (DGE) after esophagectomy and reconstruction with a gastric conduit is a common complication that occurs in 15%–39% of patients [4-6]. Although the severity of DGE varies, symptoms arising from food retention in the thorax seriously worsen patients’ QOL. In the short term, DGE can lead to anastomotic leak, pneumonia, and a longer hospital stay [5,7-9]. In the long-term, it is strongly associated with nutritional problems [10-13]. Therefore, considering these numerous sequelae, DGE should never be overlooked. The purpose of this review is to introduce DGE in a systematic manner and to help clinicians choose the most appropriate treatment through an analysis of DGE by cause. Furthermore, we would like to suggest some tips to prevent DGE.

Definition

Various studies have presented different definitions of DGE, and there are no clearly established criteria. In 1995, Finley et al. [14] defined DGE as barium retention in the gastric conduit for more than 15 minutes in a standing position after a barium swallow, and 11% of patients who underwent esophageal cancer surgery through right thoracotomy were diagnosed with DGE. In 2005, Lee et al. [15] considered DGE to be present when the 50% gastric emptying time (T50) exceeded 180 minutes in a 99m-DTPA scintigraphy study. Using this cutoff value, it was found that DGE occurred in 37.5% of patients after esophageal resection. The average T50 of this group was 422 minutes, showing a serious delay [15]. An optimal and universally accepted definition is needed to systematically classify the severity of DGE patients and to compare research results more objectively.

Pathophysiology

DGE is caused by a combination of anatomical and physiological changes in the gastric conduit after esophageal resection [3,16]. Gastric motility itself is affected by alterations of smooth muscle cells (myogenic), enteric neurons (hormonal), and the autonomic nervous system (neural). These changes are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Anatomical and physiological causes of delayed gastric emptying after esophagectomy

| Causes |

|---|

| Relaxation dysfunction of the pylorus |

| Dysfunctional peristalsis (complete vagotomy) |

| Unfavorable pressure gradient |

| : negative thoracic pressure, positive abdominal pressure |

| Torsion or angulation of the conduit |

| Redundant gastric conduit |

| Insufficient widening of esophageal hiatus |

Symptoms

As no unified definition or diagnostic criteria exist for DGE, different symptoms associated with DGE have been reported across studies [6,11,13,17,18]. Being well-informed of the symptoms related to DGE helps to educate patients regarding the changes in the body that take place in response to eating, and is useful for managing patients after surgery. When food remains in the intrathoracic gastric conduit for a long time, it can cause nausea, regurgitation, vomiting, dysphagia to solids, loss of appetite, coughing, pain, chest pressure, bloating, heartburn, early satiety, a large amount of gastric tube drainage fluid, or aspiration pneumonia [16]. The development of tools that can be used to evaluate the severity of DGE is necessary for managing those patients objectively.

Diagnosis

A chest X-ray is routinely performed during the postoperative period. Presence of the air-fluid level or dilatation in the gastric conduit strongly suggests DGE (Fig. 1). When DGE is clinically suspected, the clinician should investigate whether a mechanical obstruction may be causing the symptoms. Although there is still no clear indication for revisional surgery, if a mechanical obstruction is suspected, rather than an intrinsic functional problem of gastric conduit, it is more likely that reoperation will be appropriate.

Fig. 1.

Thoracic stomach syndrome. This is a complication that can occur after esophagectomy with whole-stomach reconstruction. The main symptom is chest discomfort after eating.

Several diagnostic modalities can be used to differentiate DGE by cause. Chest computed tomography (CT) can play an important role in ruling out whether there is any sign of mechanical obstruction in the upper gastrointestinal (GI) tract. For instance, a twisted conduit may be suspected if the lesser curve staple line is rotated on a CT scan [19]. Endoscopy is a useful tool to confirm the presence of an anastomotic stricture or narrow pyloric orifice. The presence of residual food in the gastric conduit during endoscopy despite proper fasting can also be an important clue that suggests DGE. The barium swallowing test is a non-invasive, relatively inexpensive, and easily accessible modality that can demonstrate any redundancy, kink, or herniation of the gastric conduit, as well as the level of mechanical obstruction [20]. However, this test is limited in that it can only visualize the flow of thick liquid, not solids. A quantitative evaluation provides an objective assessment of the severity of DGE. Scintigraphy using a mixed meal with a radioactive isotope has been used in several studies; this method has the advantage of being able to visualize the dynamic flow of solids, but the disadvantage of it being difficult to standardize different protocols for each institution [15,21,22]. A wireless capsule motility (SmartPill GI monitoring system; Smart Pill Corp., Buffalo, NY, USA) was designed to sense and transmit intraluminal pH, pressure, and temperature data from a capsule at regular intervals as it passes through the GI tract [23]. The diagnostic accuracy of this modality is comparable to that of gastric-emptying scintigraphy [24]. Manometry is used to access gastropyloric motor activity, which is quantified by calculating the motility index [25].

Management

In general, intrathoracic gastric motility gradually improves over a period of 6 months to 3 years after surgery [26]. Therefore, even if DGE is present, a less invasive approach, such as dietary modification, medication, or gastroscopic intervention, is considered first. In very severe cases, revisional surgery may be required to properly restore the function of the gastric conduit [19,27,28].

Dietary modifications to include smaller, more frequent, and more liquid-based meals help to reduce the severity of DGE. Soft and cooked foods consisting of low-fat and low-fiber ingredients are recommended. Isotonic food at a moderate temperature is encouraged to enhance gastric emptying [29].

Prokinetics are believed to play a role in promoting gastric contractility, enhancing gastric dysrhythmia, and improving the coordination of antral and duodenal movement [30]. Several studies have investigated various prokinetic drugs such as metoclopramide (a dopamine D2 receptor antagonist, the only drug approved by the Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of gastroparesis), domperidone (with a similar mode of action to that of metoclopramide, but not penetrating the blood-brain barrier), or cisapride [30], but there is still no clear evidence of benefits in patients with DGE after esophagectomy. In contrast, erythromycin, a motilin receptor agonist in the antrum and duodenum, proved its efficacy [21,25]. However, its use is limited by its tachyphylaxis, and its effects wane after a few weeks of daily use [31,32].

Increased pyloric resistance after complete vagotomy can be managed by endoscopic pyloric balloon dilatation (EPBD), which has been widely accepted as a safe and effective therapy [33,34]. Kim et al. [35] reported that 8% of esophagectomy patients who underwent pyloric finger fracture for pyloric drainage needed EPBD postoperatively. In a comparison of scintigraphy findings before and after the procedure, DGE improved in two-thirds of DGE patients with EPBD. Preoperative EPBD was introduced to replace the intraoperative pyloric drainage procedure [36]. Hadzijusufovic et al. [36] reported that preoperative EPBD reduced the postoperative pyloric dysfunction rate compared with the non-intervention group (13.2% versus 37.5%) and emphasized that a balloon size of 30 mm was more successful than a 20-mm balloon (93.3% versus 58.5%).

With the increasing prevalence of minimally invasive esophagectomy, intraoperative pyloric drainage procedures, including pyloroplasty, pyloromyotomy, or pyloric finger fracture, have become time-consuming and difficult to put into practice. As an alternative, intra-pyloric injection of botulinum toxin (IPBT) has been proposed; it presented a high success rate for the prevention of DGE [37,38] and showed comparable results to a surgical pyloric procedure [17]. Theoretically, botulinum toxin could weaken the pyloric smooth muscles temporarily during the early postoperative period, and the relaxing effect might disappear along with potentially decreased bile reflux and dumping syndrome within 12 weeks. However, Eldaif et al. [39] reported that although the use of IPBT significantly decreased the operative time compared to pyloromyotomy and pyloroplasty, the patients who received IPBT suffered from more reflux symptoms, had more frequent use of promotility drugs, needed more frequent endoscopic pyloric interventions, and had no benefits compared to those who underwent pyloromyotomy and pyloroplasty in terms of reducing dumping symptoms. In a well-matched cohort study, Stewart et al. [40] demonstrated a similar incidence of DGE between patients who received no pyloric intervention and those who received IPBT in the setting of minimally invasive esophagectomy.

A few case reports have shown the feasibility of electrostimulation for intractable DGE after esophagectomy [41,42]. A battery-powered neurostimulator (Enterra; Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN, USA) was implanted in the subcutaneous pocket of the abdominal wall and connected to the intrathoracic gastric antrum with 2 stimulating electrodes. Although gastric electrical stimulation treatment is an approved method for patients with idiopathic and diabetic gastroparesis [43], more evidence is needed for this technique to be applied to patients with DGE after esophagectomy.

The condition of most DGE patients improves by dietary control, lifestyle modifications, medication, or an endoscopic intervention [44]. If a patient still has serious DGE symptoms despite these conservative therapies, revisional surgery may be needed for correctable anatomical problems. Kent et al. [19] reported that 4% of esophagectomy patients underwent a revisional operation, and the identified patients had a diaphragmatic hernia, redundant gastric conduit, or both. A mechanical obstruction was observed in 54% of patients with a redundant conduit. Revisional surgery aimed to reposition the herniated organ or the excessive conduit lying horizontally over the diaphragm into the abdomen. Depending on the patient’s condition, widening of the narrow hiatal opening causing external obstruction, tailoring of the bulging conduit, or correction of the twisted conduit was performed. When performing these complex operations, the vitality of the conduit should not be affected, so both a thoracic and abdominal approach is recommended for safe dissection [27,28].

Prevention

We believe that anticipatory measures to prevent DGE are more important than curative measures. However, it is not easy to determine which surgical technique or policy is preferable as a preventive method. Below are 4 factors to consider to reduce the incidence of DGE.

Whole stomach versus gastric tube

Both the gastric tube and whole-stomach approaches have been widely used as for conduit formation. Theoretically, the whole-stomach approach provides better preservation of the submucosal vessels and can slightly increase gastric capacity [20,45]. Advocates who prefer the whole- stomach approach showed that whole-stomach patients had fewer meals and snacks per day, with faster eating and fewer complaints of early satiety [20,26]. In contrast, Zhang et al. [46] insisted that a straight, narrow conduit avoiding redundancy can be constructed by gastric tube formation, with a lower incidence of postoperative reflux esophagitis and thoracic stomach syndrome. Other studies have shown that the anatomical structure of the gastric tube is more in line with physiological needs and could reduce the incidence of postoperative complications owing to the low anastomotic tension associated with this technique [47]. Barbera et al. [48] demonstrated that a more narrow stomach enhanced the test meal with a faster emptying rate. Lee et al. [49] developed a flow visualization experimental model of a gastric conduit with variable sizes of acrylic-based photopolymer tube grafts and pyloric-mimicking openings. The authors concluded that a narrow gastric tube and/or a pyloric drainage procedure could improve gastric emptying. However, this debate has not yet been fully resolved.

Esophageal hiatus

Sufficient widening of the esophageal hiatus to 4 fingers’ width has been widely accepted. However, care must be taken because an excessively widened esophageal hiatus may cause hiatal hernia after esophagectomy. Since hiatal hernia mainly occurs on the left side, it may be more advantageous to make an incision for hiatus widening on the right side.

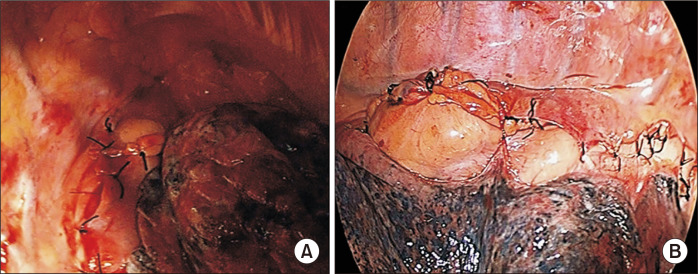

Mediastinalization

The whole stomach is larger and more distensible than a gastric tube, and therefore more susceptible to DGE by Laplace’s law [50]. Therefore, mediastinalization of the interposed stomach using mediastinal pleural coverage is an alternative method for maintaining alignment of the gastric conduit if the whole stomach is chosen as a conduit (Fig. 2). This technique is especially helpful to prevent bulging or redundancy in the whole-stomach conduit. However, if a gastric tube conduit or the McKeown operation is used, it may be omitted or non-feasible.

Fig. 2.

Mediastinalization of the interposed stomach using mediastinal pleural coverage. To do this, the mediastinal pleura should be well preserved from the beginning of esophageal dissection. (A) Upper part of the conduit. (B) Middle and lower level of the conduit.

According to Laplace’s law, reinforcing the gastric wall tension itself can lead to a rapid increase of intraluminal gastric pressure when the stomach is filled, facilitating gastric emptying [50]. The staple lines of the lesser curvature in the gastric conduit are frequently oversewn with a second layer of continuous Lembert sutures. If the surgeon thinks that the conduit is somewhat redundant after creating a gastric tube using a stapler, we recommend reducing the graft size and increasing the gastric wall tension through a continuous Lembert suture using a barbed monofilament (3-0 V-Loc 90; Medtronic). Maintenance of nasogastric tube (NGT) suction during the postoperative period can be used to keep the thoracic stomach decompressed until mediastinal fixation of the conduit [3]. When the whole stomach is used, we prefer to maintain prophylactic NGT placement to prevent the development of thoracic stomach syndrome. However, conventional NGT use in esophagectomy is still a matter of debate. Weijs et al. [51] reported that early removal of the NGT had no inferiority in terms of pulmonary complications, anastomotic leakage, and mortality compared to routine NGT use in their meta- analysis.

Pyloric drainage procedure

Pyloric interventions have been thought of as the major form of prophylaxis against DGE. There are 5 pyloric management strategies at the time of esophagectomy: no intervention [52,53], botulinum toxin injection [37], finger fracture [15], pyloroplasty [54], and pyloromyotomy [7,39]. Each method has its advantages and disadvantages, so we cannot say with certainty which one is the best. However, advocates for the no-intervention strategy have been gradually reporting convincing results [40,55,56].

Conclusion

The optimal strategy for preventing DGE is still a matter of debate among surgeons. However, there is no doubt that a straight, narrow, and mediastinalized conduit without redundancy is beneficial for gastric emptying. We are now facing the need to consistently modify esophageal surgery techniques to be suitable for the changing environment of minimally invasive surgery.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Van Hagen P, Hulshof MC, van Lanschot JJ, et al. Preoperative chemoradiotherapy for esophageal or junctional cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2074–84. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1112088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Elliott JA, Docherty NG, Eckhardt HG, et al. Weight loss, satiety, and the postprandial gut hormone response after esophagectomy: a prospective study. Ann Surg. 2017;266:82–90. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Donington JS. Functional conduit disorders after esophagectomy. Thorac Surg Clin. 2006;16:53–62. doi: 10.1016/j.thorsurg.2006.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li B, Zhang JH, Wang C, et al. Delayed gastric emptying after esophagectomy for malignancy. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2014;24:306–11. doi: 10.1089/lap.2013.0416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benedix F, Willems T, Kropf S, Schubert D, Stubs P, Wolff S. Risk factors for delayed gastric emptying after esophagectomy. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2017;402:547–54. doi: 10.1007/s00423-017-1576-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang L, Hou SC, Miao JB, Lee H. Risk factors for delayed gastric emptying in patients undergoing esophagectomy without pyloric drainage. J Surg Res. 2017;213:46–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2017.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arya S, Markar SR, Karthikesalingam A, Hanna GB. The impact of pyloric drainage on clinical outcome following esophagectomy: a systematic review. Dis Esophagus. 2015;28:326–35. doi: 10.1111/dote.12191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sutcliffe RP, Forshaw MJ, Tandon R, et al. Anastomotic strictures and delayed gastric emptying after esophagectomy: incidence, risk factors and management. Dis Esophagus. 2008;21:712–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2008.00865.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bolton JS, Conway WC, Abbas AE. Planned delay of oral intake after esophagectomy reduces the cervical anastomotic leak rate and hospital length of stay. J Gastrointest Surg. 2014;18:304–9. doi: 10.1007/s11605-013-2322-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McLarty AJ, Deschamps C, Trastek VF, Allen MS, Pairolero PC, Harmsen WS. Esophageal resection for cancer of the esophagus: long-term function and quality of life. Ann Thorac Surg. 1997;63:1568–72. doi: 10.1016/S0003-4975(97)00125-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gockel I, Gonner U, Domeyer M, Lang H, Junginger T. Long-term survivors of esophageal cancer: disease-specific quality of life, general health and complications. J Surg Oncol. 2010;102:516–22. doi: 10.1002/jso.21434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deldycke A, van Daele E, Ceelen W, van Nieuwenhove Y, Pattyn P. Functional outcome after Ivor Lewis esophagectomy for cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2016;113:24–8. doi: 10.1002/jso.24084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anandavadivelan P, Wikman A, Johar A, Lagergren P. Impact of weight loss and eating difficulties on health-related quality of life up to 10 years after oesophagectomy for cancer. Br J Surg. 2018;105:410–8. doi: 10.1002/bjs.10686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Finley FJ, Lamy A, Clifton J, Evans KG, Fradet G, Nelems B. Gastrointestinal function following esophagectomy for malignancy. Am J Surg. 1995;169:471–5. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9610(99)80197-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee HS, Kim MS, Lee JM, Kim SK, Kang KW, Zo JI. Intrathoracic gastric emptying of solid food after esophagectomy for esophageal cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 2005;80:443–7. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2005.02.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Konradsson M, Nilsson M. Delayed emptying of the gastric conduit after esophagectomy. J Thorac Dis. 2019;11(Suppl 5):S835–44. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2018.11.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bagheri R, Fattahi SH, Haghi SZ, et al. Botulinum toxin for prevention of delayed gastric emptying after esophagectomy. Asian Cardiovasc Thorac Ann. 2013;21:689–92. doi: 10.1177/0218492312468438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burrows WM. Gastrointestinal function and related problems following esophagectomy. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2004;16:142–51. doi: 10.1053/j.semtcvs.2004.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kent MS, Luketich JD, Tsai W, et al. Revisional surgery after esophagectomy: an analysis of 43 patients. Ann Thorac Surg. 2008;86:975–83. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2008.04.098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Collard JM, Tinton N, Malaise J, Romagnoli R, Otte JB, Kestens PJ. Esophageal replacement: gastric tube or whole stomach? Ann Thorac Surg. 1995;60:261–6. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(95)00411-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Burt M, Scott A, Williard WC, et al. Erythromycin stimulates gastric emptying after esophagectomy with gastric replacement: a randomized clinical trial. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1996;111:649–54. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5223(96)70318-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nishikawa M, Murakami T, Tangoku A, Hayashi H, Adachi J, Suzuki T. Functioning of the intrathoracic stomach after esophagectomy. Arch Surg. 1994;129:837–41. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1994.01420320063012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cassilly D, Kantor S, Knight LC, et al. Gastric emptying of a non-digestible solid: assessment with simultaneous SmartPill pH and pressure capsule, antroduodenal manometry, gastric emptying scintigraphy. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2008;20:311–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2007.01061.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maqbool S, Parkman HP, Friedenberg FK. Wireless capsule motility: comparison of the SmartPill GI monitoring system with scintigraphy for measuring whole gut transit. Dig Dis Sci. 2009;54:2167–74. doi: 10.1007/s10620-009-0899-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nakabayashi T, Mochiki E, Garcia M, et al. Gastropyloric motor activity and the effects of erythromycin given orally after esophagectomy. Am J Surg. 2002;183:317–23. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9610(02)00796-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Collard JM, Romagnoli R, Otte JB, Kestens PJ. The denervated stomach as an esophageal substitute is a contractile organ. Ann Surg. 1998;227:33–9. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199801000-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rove JY, Krupnick AS, Baciewicz FA, Meyers BF. Gastric conduit revision postesophagectomy: management for a rare complication. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2017;154:1450–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2017.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schaheen LW, Joubert KD, Luketich JD. Revising a gastric conduit after esophagectomy: how do we get it right? J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2017;154:1461–2. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2017.05.092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tang DM, Friedenberg FK. Gastroparesis: approach, diagnostic evaluation, and management. Dis Mon. 2011;57:74–101. doi: 10.1016/j.disamonth.2010.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Parkman HP, Hasler WL, Fisher RS American Gastroenterological Association. medical position statement: diagnosis and treatment of gastroparesis. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:1589–91. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.09.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dhir R, Richter JE. Erythromycin in the short- and long-term control of dyspepsia symptoms in patients with gastroparesis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2004;38:237–42. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200403000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weber FH, Jr, Richards RD, McCallum RW. Erythromycin: a motilin agonist and gastrointestinal prokinetic agent. Am J Gastroenterol. 1993;88:485–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lanuti M, DeDelva P, Morse CR, et al. Management of delayed gastric emptying after esophagectomy with endoscopic balloon dilatation of the pylorus. Ann Thorac Surg. 2011;91:1019–24. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2010.12.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Swanson EW, Swanson SJ, Swanson RS. Endoscopic pyloric balloon dilatation obviates the need for pyloroplasty at esophagectomy. Surg Endosc. 2012;26:2023–8. doi: 10.1007/s00464-012-2151-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim JH, Lee HS, Kim MS, Lee JM, Kim SK, Zo JI. Balloon dilatation of the pylorus for delayed gastric emptying after esophagectomy. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2008;33:1105–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2008.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hadzijusufovic E, Tagkalos E, Neumann H, et al. Preoperative endoscopic pyloric balloon dilatation decreases the rate of delayed gastric emptying after Ivor-Lewis esophagectomy. Dis Esophagus. 2019;32:doy097. doi: 10.1093/dote/doy097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Martin JT, Federico JA, McKelvey AA, Kent MS, Fabian T. Prevention of delayed gastric emptying after esophagectomy: a single center's experience with botulinum toxin. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;87:1708–13. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2009.01.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kent MS, Pennathur A, Fabian T, et al. A pilot study of botulinum toxin injection for the treatment of delayed gastric emptying following esophagectomy. Surg Endosc. 2007;21:754–7. doi: 10.1007/s00464-007-9225-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Eldaif SM, Lee R, Adams KN, et al. Intrapyloric botulinum injection increases postoperative esophagectomy complications. Ann Thorac Surg. 2014;97:1959–64. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2013.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stewart CL, Wilson L, Hamm A, et al. Is chemical pyloroplasty necessary for minimally invasive esophagectomy? Ann Surg Oncol. 2017;24:1414–8. doi: 10.1245/s10434-016-5742-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Salameh JR, Aru GM, Bolton W, Abell TL. Electrostimulation for intractable delayed emptying of intrathoracic stomach after esophagectomy. Ann Thorac Surg. 2008;85:1417–9. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2007.09.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Asti E, Lovece A, Bonavina L. Thoracoscopic implant of neurostimulator for delayed gastric conduit emptying after esophagectomy. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2016;26:299–301. doi: 10.1089/lap.2016.0089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Patel R, Kulkarni P. The Enterra device and the future of gastric electrical pacing. J Gastric Disord Ther. 2016;2:2–5. doi: 10.16966/2381-8689.127. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Baker A, Wooten LA, Malloy M. Nutritional considerations after gastrectomy and esophagectomy for malignancy. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2011;12:85–95. doi: 10.1007/s11864-010-0134-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pierie JP, de Graaf PW, van Vroonhoven TJ, Obertop H. The vascularization of a gastric tube as a substitute for the esophagus is affected by its diameter. Dis Esophagus. 1998;11:231–5. doi: 10.1093/dote/11.4.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang W, Yu D, Peng J, Xu J, Wei Y. Gastric-tube versus whole-stomach esophagectomy for esophageal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0173416. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0173416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shu YS, Sun C, Shi WP, Shi HC, Lu SC, Wang K. Tubular stomach or whole stomach for esophagectomy through cervico-thoraco-abdominal approach: a comparative clinical study on anastomotic leakage. Ir J Med Sci. 2013;182:477–80. doi: 10.1007/s11845-013-0917-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Barbera L, Kemen M, Wegener M, Jergas M, Zumtobel V. Effect of site and width of stomach tube after esophageal resection on gastric emptying. Zentralbl Chir. 1994;119:240–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lee JI, Choi S, Sung J. A flow visualization model of gastric emptying in the intrathoracic stomach after esophagectomy. Ann Thorac Surg. 2011;91:1039–45. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2010.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bemelman WA, Verburg J, Brummelkamp WH, Klopper PJ. A physical model of the intrathoracic stomach. Am J Physiol. 1988;254(2 Pt 1):G168–75. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1988.254.2.G168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Weijs TJ, Kumagai K, Berkelmans GH, Nieuwenhuijzen GA, Nilsson M, Luyer MD. Nasogastric decompression following esophagectomy: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Dis Esophagus. 2017;30:1–8. doi: 10.1111/dote.12530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fritz S, Feilhauer K, Schaudt A, et al. Pylorus drainage procedures in thoracoabdominal esophagectomy: a single-center experience and review of the literature. BMC Surg. 2018;18:13. doi: 10.1186/s12893-018-0347-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lanuti M, de Delva PE, Wright CD, et al. Post-esophagectomy gastric outlet obstruction: role of pyloromyotomy and management with endoscopic pyloric dilatation. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2007;31:149–53. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2006.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Murphy TJ, Levy RM, Crist LR, Luketich JD. Minimally invasive pyloroplasty. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010;22:338–40. doi: 10.1053/j.semtcvs.2011.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Palmes D, Weilinghoff M, Colombo-Benkmann M, Senninger N, Bruewer M. Effect of pyloric drainage procedures on gastric passage and bile reflux after esophagectomy with gastric conduit reconstruction. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2007;392:135–41. doi: 10.1007/s00423-006-0119-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nguyen NT, Dholakia C, Nguyen XM, Reavis K. Outcomes of minimally invasive esophagectomy without pyloroplasty: analysis of 109 cases. Am Surg. 2010;76:1135–8. doi: 10.1177/000313481007601026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]