Highlights

-

•

The transmission onset of COVID-19 relative to the symptom onset is noteworthy.

-

•

We inferred transmission onset time from 72 infector-infectee pairs with defined contact history.

-

•

The median transmission onset was 1.31 days after, and the peak was 0.72 days before the symptom onset.

-

•

The pre-symptomatic transmission proportion was 37% (95% CI, 16–52%).

-

•

The transmission onset peaked with the symptom onset and the pre-symptomatic transmission proportion is substantial.

Keywords: COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, Infectious disease transmission, Infectious disease incubation period

Abstract

Objectives

The distribution of the transmission onset of COVID-19 relative to the symptom onset is a key parameter for infection control. It is often not easy to study the transmission onset time, as it is difficult to know who infected whom exactly when.

Methods

We inferred transmission onset time from 72 infector-infectee pairs in South Korea, either with known or inferred contact dates, utilizing the incubation period. Combining this data with known information of the infector's symptom onset, we could generate the transmission onset distribution of COVID-19, using Bayesian methods. Serial interval distribution could be automatically estimated from our data.

Results

We estimated the median transmission onset to be 1.31 days (standard deviation, 2.64 days) after symptom onset with a peak at 0.72 days before symptom onset. The pre-symptomatic transmission proportion was 37% (95% credible interval [CI], 16–52%). The median incubation period was estimated to be 2.87 days (95% CI, 2.33–3.50 days), and the median serial interval to be 3.56 days (95% CI, 2.72–4.44 days).

Conclusions

Considering that the transmission onset distribution peaked with the symptom onset and the pre-symptomatic transmission proportion is substantial, the usual preventive measures might be too late to prevent SARS-CoV-2 transmission.

Introduction

SARS-CoV-2, a novel coronavirus first reported in Wuhan City, China in December 2019, has been spreading globally; the World Health Organization declared it as a pandemic on March 11, 2020 (World Health Organization, 2020a; Zhu et al., 2020). A total of 3,096,626 cases of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and 217,896 confirmed deaths were counted world wide by April 30, 2020 (World Health Organization, 2020b).

Considering its global threat, the transmission dynamics of COVID-19 should be made explicit. There have been studies reporting the estimated serial interval and incubation period, based on the early epidemics in China (Backer et al., 2020, Lauer et al., 2020, Li et al., 2020, Nishiura et al., 2020). The serial interval is the duration between the symptom onset of successive cases; the incubation period is the time since infection to the symptom onset. Those are key epidemiological parameters that give essential insight to infer the transmission potential and determine the quarantine duration (White and Pagano, 2008).

There have been multiple reports of pre-symptomatic transmission of SARS-CoV-2, highlighting the difficulty of containment and mitigation of the disease (He et al., 2020, Liu et al., 2020, Wei et al., 2020). However, transmission onset distribution of COVID-19 has never been studied before. It is not easy to study the transmission onset time, as it is difficult to know who infected whom exactly when. In this report, we tried to estimate the transmission onset distribution relative to the symptom onset, using robust epidemiologic data of infector-infectee pairs in South Korea.

Methods

Data

We searched public reports of confirmed COVID-19 patients by the government and each municipal website in South Korea (Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020; Seoul Metropolitan Government, 2020; Gyeonggi Provincial Government, 2020a,b). As of March 31, 2020, there were 9887 confirmed cases, of which 8260 (83.5%) were linked to specific clusters such as religious groups, hospitals, or long-term healthcare facilities (Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020). Five-hundred and sixty cases (5.7%) were imported from abroad (Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020). We screened all available cases between January 23 to March 31, 2020, and selected the pairs with a clearly defined contact history. We excluded cases from main clusters unless the causal relationship between an infector and infectee pair was evident.

For each pair of cases, we collected information on symptom onset dates of both the infector and the infectee, exposure dates of the infectee by the infector, and the confirmation dates of both. Considering the South Korean quarantine policy, the confirmation date could be regarded as the date on which isolation started. Demographic information on age and sex were also gathered.

Procedures

We tried to estimate the time difference between an infector’s symptom onset and its transmission onset time. We defined symptom onset date , an infectee’s infection date , an infector’s transmission onset date , and contact time of the pair as , where subscripts L and R denote the left and right boundaries, meaning the earliest and the latest contact dates respectively. The aim of the study is to estimate the timing of relative to the , which we denominate as . We put as an infectee and as the corresponding infector, and observed . should be within the interval , and transmission onset of an infector () is described as . Using the pair , we were able to estimate the distribution ) of .

There are three possible scenarios for in our data.

-

(i)

There is an exact calendar date of exposure. In this case, we could directly determine the timing of transmission as .

-

(ii)

There is a specified duration of exposure .

-

(iii)

There is a continuous exposure such as household members .

Recall that the aim is to estimate the distribution of based on the data for infectees. We employed the following parametric model for :

where , , , is the gamma distribution with the parameter , and is the uniform distribution with the support . In the model, is the shift parameter for cases with transmission before symptom onset. We introduced the term to make the effect of negative outliers of be minimal to estimate the parameter. That is, we considered to be an outlier if . In the model, is an arbitrary limit for an outlier of W. In the analysis, we used , since the usual incubation period is within 14 days.

A difficulty in estimating is that the exact is not observed for cases in categories (ii) and (iii). However, conceptually we could impute the timing of transmission by use of the estimated incubation period distribution (Reich et al., 2009). With our notation, is the incubation period. From our data of contact dates and symptom onset dates, we could estimate the distribution of Z, which we utilized to impute . That is, in case (ii), we could generate from the conditional probability distribution , and then we let . Similarly, we could generate from the conditional probability distribution for case (iii). To accommodate this idea, we used a Bayesian method and obtained the posterior distribution of based on the Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) algorithm in which is imputed for cases in categories (ii) and (iii). A detailed description of the MCMC algorithm is provided in the Supplementary Material.

For sensitivity analysis, we utilized the incubation period distribution from a previous study and replicated the same analysis as above (Lauer et al., 2020). Moreover, we hold the parameter as 4, and compared the result using the same procedure, since the minimum of from our data was −4 days. Serial interval distribution could be automatically estimated from our data.

All analyses were conducted using the R statistical software version 3.6.3. All code and data are available in the Supplementary Material. We present case numbers with a randomization process, instead of nationally designated identification numbers, in order to maintain confidentiality.

Ethics approval

All the data used in this study were publicly available and approved by the National Cancer Center's institutional review board assessment (NCC2020-0119).

Results

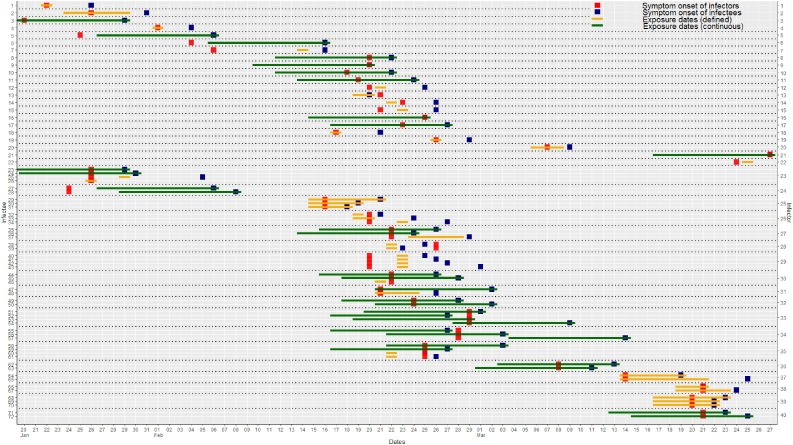

We found 89 infectees with a defined source of infection (infector) and contact history. Four infectors (4.5%) were asymptomatic until diagnosed and thus were excluded from the analysis. Sixteen infectees (18.0%) were asymptomatic when diagnosed, among which 13 cases had no specified contact date and were unable to guess the infection time. In sum, 72 infector-infectee pairs were included in the study (Figure 1 ).

Figure 1.

Transmission plot of infector-infectee pairs. For cases of continuous exposure, the interval presentation was limited to 10 days before the symptom onset, whoever came first. The upper 95th percentile of the pre-estimated incubation period is 10.1.

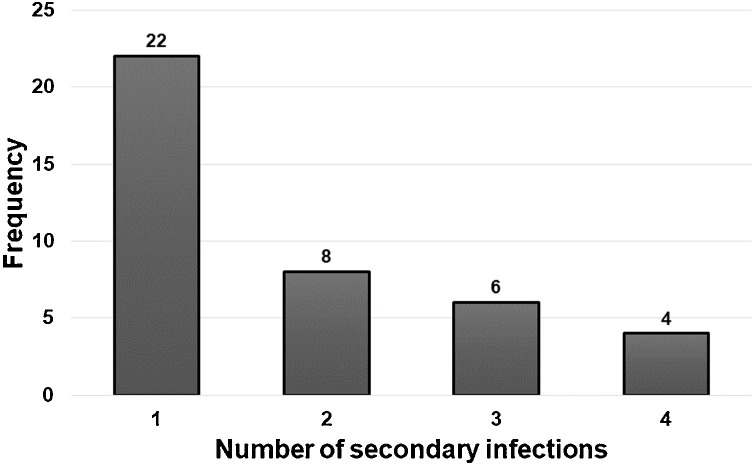

Twenty-two cases documented a single point date of contact, and 16 cases had a documented duration of contact dates. Otherwise, 34 cases (32 household members and two colleagues) had continuous exposure history (Supplementary Material). The median age of the 72 infectees was 40 years (interquartile range [IQR], 24–54 years). Of these, 34 (47%) were male, and 38 (53%) were female. The infectees had 40 unique infectors. The average number of transmissions per infector was 1.8, with a maximum of four cases (Figure 2 ).

Figure 2.

The number of secondary infections per infector in the reported data set.

We estimated the incubation period distribution of COVID-19 using a lognormal model. Among 35 pairs with given contact dates, the median incubation period was 2.87 days (95% credible interval [CI], 2.33–3.50) (Table 1 ). The estimated median serial interval from 69 infector-infectee pairs with given symptom onset dates was 3.56 days (95% CI, 2.72–4.44), with the best-fit using a lognormal distribution (Table 2 ).

Table 1.

Estimated incubation period distributions for COVID-19 based on 35 infector-infectee pairs with defined contact dates.

| Lognormal | Gamma | Weibull | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median (95% CI) | 2.87 (2.33–3.50) | 2.99 (2.44–3.60) | 3.10 (2.54–3.71) |

| Parameter 1 | 1.055 (0.845–1.254) | 4.544 (2.590–10.494) | 2.310 (1.747–3.743) |

| Parameter 2 | 0.493 (0.301–0.643) | 0.709 (0.312–1.178) | 3.635 (3.030–4.208) |

| Log-likelihood | −46.6 | −45.4 | −45.1 |

For the lognormal distribution, parameter 1 and parameter 2 are the mean and SD of the natural logarithm; for all other distributions, parameter 1 and parameter 2 are the shape and scale parameters, respectively.

Table 2.

Estimated serial interval distributions for COVID-19 based on 69 infector-infectee pairs with symptom onset dates.

| Lognormal | Gamma | Weibull | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median (95% CI) | 3.56 (2.72–4.44) | 3.75 (2.87–4.72) | 3.93 (3.04–4.92) |

| Parameter 1 | 3.18 (2.22–4.24) | 3.45 (2.56–5.19) | 1.96 (1.64–2.44) |

| Parameter 2 | 0.75 (0.47–1.03) | 2.19 (1.44–2.91) | 8.47 (7.53–9.53) |

| Log-likelihood | −77.5 | −192.8 | −189.8 |

For the lognormal distribution, parameter 1 and parameter 2 are the mean and SD of the natural logarithm; for all other distributions, parameter 1 and parameter 2 are the shape and scale parameters, respectively.

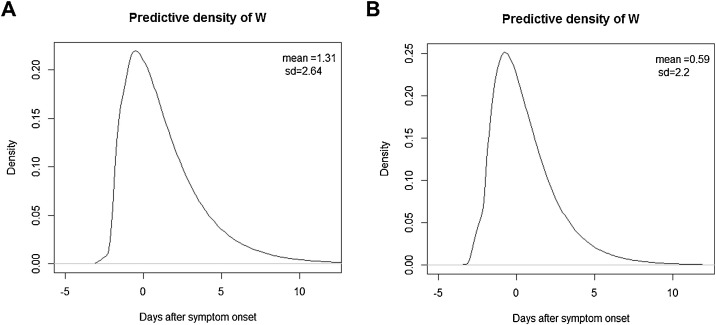

Based on the 72 infector-infectee pairs, the Bayes estimate of the transmission onset distribution after a smoothing procedure is given in Figure 3 A. The mean and median values were 1.31 days (95% CI, 0.38–2.55) and 0.68 days (95% CI, −0.09 to 1.73) after infectors’ symptom onset, respectively, with the peak at 0.72 days before symptom onset. The pre-symptomatic transmission proportion was 37% (95% CI, 16–52%).

Figure 3.

Estimated distribution of the transmission onset of COVID-19 relative to the symptom onset (A) using the incubation period distribution in the current study, and (B) using the previous incubation period distribution (Lauer et al., 2020).

For sensitivity analysis, applying the incubation period of the previous study, the transmission onset distribution was inferred as shown in Figure 3B. The mean and median values were 0.59 days (95% CI, −0.33 to 1.79) and 0.12 days (95% CI, −0.75 to 1.06) after the infector’s symptom onset, respectively, with the peak at 0.41 days before symptom onset. The pre-symptomatic transmission proportion was 48% (95% CI, 29–67%). With a fixed parameter of as 4, the mean and median were 0.59 (95% CI, −0.34 to 1.79) and −0.07 days (95% CI, −0.91 to 0.99), with the pre-symptomatic transmission proportion of 51% (95% CI, 37–64%).

Discussion

The transmission onset distribution is of utmost interest to clinicians and public health workers, but it has not yet been widely studied due to a lack of epidemiological information. Based on actual data, we herewith provide evidence that the transmission of COVID-19 can start before symptom onset, and the probability peaks at the symptom's start and declines after that. Interestingly, this distribution trend looks similar to published SARS-CoV-2 viral load kinetics although it could not include the viral load data before the symptom onset (Kim et al., 2020, Zou et al., 2020).

In South Korea, the first COVID-19 case was identified on January 19, 2020, in a traveler from Wuhan City, who was quarantined immediately after airport screening. Until February 18, 2020, there were only imported cases from abroad or cases from their close contacts who were under surveillance. The situation was totally changed after an outbreak with an unknown source of infection occurred in a religious community, resulting in a total of 5210 confirmed cases in that single cluster as of April 12, 2020, a number which was almost half (49.6%) of the total 10,512 cases in South Korea (Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020). This study spanned from late January to the end of March 2020, and encompassed all the phases observed in South Korea, thus enhancing the reliability of the results. Furthermore, in South Korea, close contacts of confirmed patients were screened extensively with SARS-CoV-2 nucleic acid testing, regardless of whether they had symptoms. Given this situation, it can be assumed that cases of infection are unlikely to have been missed.

Among the 89 infectors, four cases (4.5%) were asymptomatic when diagnosed, but out of 89 infectees, 16 cases (18.0%) were asymptomatic when diagnosed. The difference is attributed to the active surveillance of close contacts of COVID-19 patients, including screening tests of those asymptomatic, and in turn, pre-symptomatic. Our study revealed that approximately 40% of individuals with COVID-19 infected others when they (infectors) could not acknowledge any symptom. This finding is in line with other recently published studies revealing a pre-symptomatic transmission ratio of 46% (95% CI, 21–46%), 44% (95% CI, 25–69%) in China, and 48% (95% CI, 32–67%) in Singapore (Ganyani et al., 2020, He et al., 2020, Liu et al., 2020).

This study has several limitations. First, the dates of symptom onset and contact time were identified from the epidemiological investigation, and it could be false due to recall bias. Second, we only collected data from definite infector-infectee pairs with defined contact times. Hence, our estimation of transmission onset distribution is the upper bound of the actual value. Third, considering the substantial proportion of pre-symptomatic transmission, it is possible that a single infectee had multiple infectors, and so-called effective contacts could not be identified. Fourth, we excluded clustered data to promote the accuracy of causal relationships. The transmission behavior of SARS-CoV-2 might have different characteristics within unique clusters, but this could not be measured in this study. Fifth, we might have missed late-onset transmission cases, considering the pre-emptive screening and isolation measures implemented in South Korea.

This study provides an important message in terms of public health practice. It indicates that the usual preventive measure of isolating people when they become symptomatic might be too late to prevent SARS-CoV-2 transmission.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (No. 2020R1A2C3A01003550).

Conflict of interests

None declared.

Data availability

All code and data are available in the Supplementary Materials. We present case numbers with a randomization process, instead of nationally designated identification numbers, in order to maintain confidentiality.

Author contributions

J.Y.C. and Y.K. conceived of the study, and G.B. performed the analysis. J.Y.C. and G.B. wrote the first draft of the manuscript. Y.K. reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors interpreted the findings, contributed to writing the manuscript, and approved the final version for publication.

Acknowledgment

We acknowledge public health authorities in South Korea for their innumerable efforts to perform an epidemiologic investigation to stop the COVID-19 outbreak.

Footnotes

Supplementary material related to this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2020.07.075.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are Supplementary data to this article:

References

- Coronavirus Disease-19, Republic of Korea; Available from: http://ncov.mohw.go.kr/. [Accessed 12 April 2020].

- Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Situation Report–52; Available from: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200312-sitrep-52-covid-19.pdf?sfvrsn=e2bfc9c0_4. [Accessed 30 March 2020].

- https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) Pandemic; Available from: . [Accessed 7 May 2020].

- COVID-19 Response Status; Available from: https://blog.naver.com/gyeonggi_gov/221856148207. [Accessed 10 April 2020].

- COVID-19 Situation Report (Gyeonggi); Available from: https://www.gg.go.kr/bbs/board.do?bsIdx=722&menuId=2903#page=21. [Accessed 10 April 2020].

- COVID-19 Situation Report (Seoul); Available from: http://www.seoul.go.kr/coronaV/coronaStatus.do. [Accessed 10 April 2020].

- Backer J.A., Klinkenberg D., Wallinga J. Incubation period of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) infections among travellers from Wuhan, China, 20-28 January 2020. Euro Surveill. 2020;25(5) doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.5.2000062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganyani T., Kremer C., Chen D., Torneri A., Faes C., Wallinga J. Estimating the generation interval for COVID-19 based on symptom onset data. MedRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.29.2001269. 2020.03.05.20031815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He X., Lau E.H.Y., Wu P., Deng X., Wang J., Hao X. Temporal dynamics in viral shedding and transmissibility of COVID-19. Nat Med. 2020;26(5):672–675. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0869-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim E.S., Chin B.S., Kang C.K., Kim N.J., Kang Y.M., Choi J.P. Clinical course and outcomes of patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection: a preliminary report of the first 28 patients from the Korean Cohort Study on COVID-19. J Korean Med Sci. 2020;35(13):e142. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2020.35.e142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauer S.A., Grantz K.H., Bi Q., Jones F.K., Zheng Q., Meredith H.R. The incubation period of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) from publicly reported confirmed cases: estimation and application. Ann Intern Med. 2020;172(9):577–582. doi: 10.7326/M20-0504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q., Guan X., Wu P., Wang X., Zhou L., Tong Y. Early transmission dynamics in Wuhan, China, of novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(13):1199–1207. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., n null, Funk S., Flasche S. The contribution of pre-symptomatic infection to the transmission dynamics of COVID-2019 [version 1; peer review: 1 approved] Wellcome Open Res. 2020;5(58) doi: 10.12688/wellcomeopenres.15788.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishiura H., Linton N.M., Akhmetzhanov A.R. Serial interval of novel coronavirus (COVID-19) infections. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;93:284–286. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.02.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reich N.G., Lessler J., Cummings D.A., Brookmeyer R. Estimating incubation period distributions with coarse data. Stat Med. 2009;28(22):2769–2784. doi: 10.1002/sim.3659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei W.E., Li Z., Chiew C.J., Yong S.E., Toh M.P., Lee V.J. Pre-symptomatic transmission of SARS-CoV-2-Singapore, January 23-March 16, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(14):411–415. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6914e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White L.F., Pagano M. A likelihood-based method for real-time estimation of the serial interval and reproductive number of an epidemic. Stat Med. 2008;27(16):2999–3016. doi: 10.1002/sim.3136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu N., Zhang D., Wang W., Li X., Yang B., Song J. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(8):727–733. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou L., Ruan F., Huang M., Liang L., Huang H., Hong Z. SARS-CoV-2 viral load in upper respiratory specimens of infected patients. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(12):1177–1179. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2001737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All code and data are available in the Supplementary Materials. We present case numbers with a randomization process, instead of nationally designated identification numbers, in order to maintain confidentiality.