Sir,

Lockdown is “ an official order to control the movement of people or vehicles because of a dangerous situation” as defined by the Oxford Learners’ Dictionary.[1] In the case of the COVID-19 pandemic, a lockdown would restrict mass movements to help alleviate the spread of the infection. This sort of restriction is done by “stay home orders” or “movement control orders”.[2] Like in case of natural disasters such as earthquakes, floods and storms, lockdowns as a result of pandemics may become a fertile ground for several psychological disorders. A lockdown can be the best action at the time of such a crisis to save lives. However, both the pandemic and the lockdown may present with complex challenges to mental health that may go far beyond worrying about the crisis to worrying about administration reaction time and the future.[3,4] The multitude of effects may include inciting fear, phobia, and anxiety amongst people.[5] Loneliness, which is an important indicator for social wellbeing, would be a common experience to many at this time of lockdown. Loneliness itself can give rise to or escalate physical and psychological issues.[6] Literature suggests that during such situations, persons may suffer from adverse psychological outcomes such as anger, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder. Factors like the duration of staying at home, fear of infection, worry about ample home supplies, worry about receiving timely information, monetary loss, and stigma related to the pandemic can trigger psychological disturbances.[4,7] Decreased financial security and mindset switch from living to survival are the other factors which contribute to mental health issues.[8] Also, unemployment due to lockdown can cause low self-esteem and physical health consequences.[9] In a recent study,[10] it was found that depression and anxiety were significantly increased after the announcement of lockdown. Amongst persons under 35 years of age, factors like living alone or with children and those who are affected more financially appear to be most at risk of developing depression and anxiety.[10] During the lockdown period, people may have difficulty in sleeping, concentrating at household work and may have alcohol or substance withdrawal issues or indulge in such use. Patients with a previous history of medical or psychiatric illness may have problems such as being more irritable, withdrawn, and have difficulty accessing treatment facilities or procuring medications. This could lead to relapse of illness.[11]

Children and elderly persons may be highly vulnerable to mental health issues during this phase. Children who are in the active stages of their lives are at homes due to closure of schools. This may lead to them being confined in a closed milieu making them deficient of stimulation and interaction with their peers, both of which are essential for their mental health. They may experience anxiety, fear of getting infected, fear that someone in their family will die, and the fear of going for treatment, just like adults do. Children may model the behaviour of their anxious parents and be stressed during these times. The elderly population is also a highly vulnerable group, especially the ones who have preexisting physical illnesses. Many of them would have already been experiencing reduced social interaction and the current scenario would intensify the negative impact of social isolation on their psychological health, making them prone to depression and anxiety disorders. The lockdown may induce fear, anxiety, and acute stress,[12,13] particularly when the information that elderly population are more affected[14] is delivered to them via their family, friends, media, or internet sources.

Social isolation, loneliness, physical inactivity, or sedentary lifestyle, although are inter-related, are individual entities. Owing to the present social isolation where the public interaction is restricted, the above can interplay and interfere in health status of the person as a whole and we believe it will have effects on musculoskeletal pain. Smith et al.,[15] in their study, accomplished that although people who suffer from long-lasting musculoskeletal pain have a higher risk of being lonely, they have a lower chance of being socially isolated. Another study which assessed the health risks associated with social isolation concluded that socially isolated people irrespective of their age had relatively higher risks of impaired self-rated health and musculoskeletal issues.[16] The literature is ambiguous to explore a cause and effect relationship between musculoskeletal pain and isolation. However, the imposed restriction on social interaction and outdoor activities will eventually have twofold manifestation. It would affect an individual’s pain threshold as evidenced by increased inflammatory and pain modulating markers level, especially in those who are already suffering from chronic pain syndromes.[17] Also, the lack of physical activity because of the current restrictions would lead to musculoskeletal pain especially upper and lower backache.

FIGHTING THESE EFFECTS OF THE LOCKDOWN

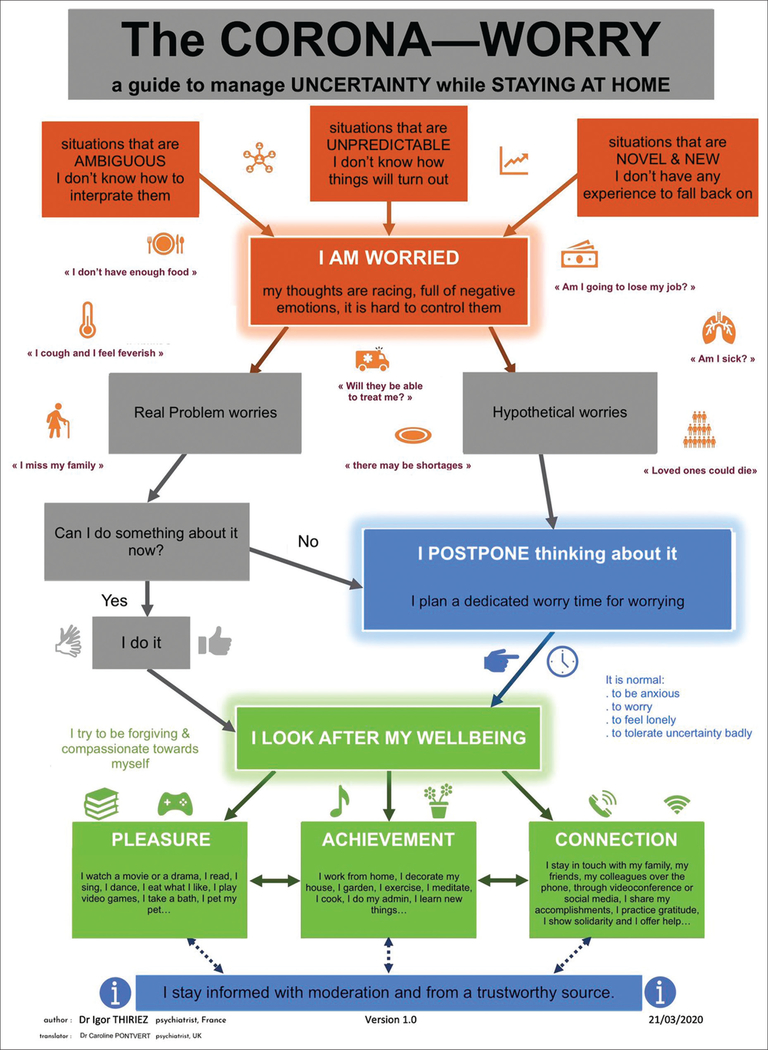

Maintaining social contact and routines may be essential for maintaining mental health. In conditions like in the current lockdown period in India, this may not be possible. Hence, staying linked with acquaintances and family members online or via phone may be worthwhile. An interesting diagrammatic representation on how to manage uncertainty while staying at home during the lockdown periods, prepared by Dr. Igor Thiriez, a psychiatrist from France and translated by Dr. Caroline Pontvert, a psychiatrist from the United Kingdom is shown in Figure 1.[18,19]

Figure 1:

The corona-worry (with permission from Dr. Igor Thiriez).

In case of children, fear and panic may be reduced by adequate care and attention, making them understand the current situation in simple ways and maintaining honesty.[10] Children may also spend more time outside home during a pandemic due to lack of awareness of the gravity of the situation and become hosts of COVID-19. To avoid such occurrences, certain interventions such as paid leave for parents may be beneficial.[20] For older persons, approaches such as physical exercises, keeping routines at home, and maintaining social connectivity if they are acquainted with gadgets may help.[10] Early detection and awareness of psychological wellbeing can go a long way in minimising the risk and improving the wellbeing of society.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This work was supported by India-US Fogarty Training in Chronic Non-Communicable Disorders & Diseases Across Lifespan Grant # 1D43TW009120 (SS Bhandari, Fellow; LB Cottler, PI).

Source of support: This work was supported by India-US Fogarty Training in Chronic Non-Communicable Disorders & Diseases Across Lifespan Grant # 1D43TW009120 (SS Bhandari, Fellow; LB Cottler, PI).

Footnotes

Declaration of interest: None.

REFERENCES

- 1.Oxford Learner’s Dictionaries. Lockdown noun [Internet]. Oxford University Press; 2020. [cited 2020 Apr 6]. Available from: https://www.oxfordlearnersdictionaries.com/definition/english/lockdown?q=lockdown [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wikipedia. Stay-at-home order [Internet]. 2020. [cited 6 April 2020]. Available from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stay-at-home_order

- 3.Jones NM, Thompson RR, Schetter CD, Silver RC. Distress and rumor exposure on social media during a campus lockdown. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America (PNAS) [Internet]. 2017. Oct 31 [cited 2020 Apr 6];114(44):11663–8. Available from: 10.1073/pnas.1708518114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Joseph SJ, P G, Bhandari SS, Dutta S. How the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) could have a quivering impact on mental health? Open J Psychiatry Allied Sci [serial online]. 2020. Mar 27 [cited 2020 Apr 6]. [Epub ahead of print]. Available from: https://www.ojpas.com/get_file.php?id=34032267&vnr=836972 [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Person B, Sy F, Holton K, Govert B, Liang A; National Center for Inectious Diseases/SARS Community Outreach Team. Fear and stigma: the epidemic within the SARS outbreak. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10:358–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mushtaq R, Shoib S, Shah T, Mushtaq S. Relationship between loneliness, psychiatric disorders and physical health? A review on the psychological aspects of loneliness. J Clin Diagn Res. 2014;8:WE01–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brooks SK, Webster RK, Smith LE, Woodland L, Wessely S, Greenberg N, et al. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. Lancet. 2020;395:912–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hawryluck L, Gold WL, Robinson S, Pogorski S, Galea S, Styra R. SARS control and psychological effects of quarantine, Toronto, Canada. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10:1206–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Linn MW, Sandifer R, Stein S. Effects of unemployment on mental and physical health. Am J Public Health. 1985;75:502–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Armour S Depression and anxiety spiked after lockdown announcement, coronavirus mental health study shows [Internet]. The University of Sheffield; 2020. Mar 31 [cited 2020 Apr 6]. Available from: https://www.sheffield.ac.uk/news/nr/depression-anxiety-spiked-after-lockdown-announcementcoronavirus-mental-health-psychology-study-1.885549

- 11.Minding our minds during the COVID-19 [Internet]. 2020. [cited 2020 Apr 6]. Available from: https://www.mohfw.gov.in/pdf/MindingourmindsduringCoronaeditedat.pdf

- 12.World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe. Mental health and psychological resilience during the COVID-19 pandemic [Internet]. 2020. [cited 2020 Apr 6]. Available from: http://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/health-emergencies/coronavirus-covid-19/news/news/2020/3/mental-health-andpsychological-resilience-during-the-covid-19-pandemic

- 13.Santini ZI, Jose PE, York Cornwell E, Koyanagi A, Nielsen L, Hinrichsen C, et al. Social disconnectedness, perceived isolation, and symptoms of depression and anxiety among older Americans (NSHAP): a longitudinal mediation analysis. Lancet Public Health. 2020;5:e62–e70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Worldometer. Coronavirus age, sex, demographics (COVID-19) [Internet]. 2020. [cited 2020 Apr 6]. Available from: https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/coronavirus-age-sex-demographics/

- 15.Smith TO, Dainty JR, Williamson E, Martin KR. Association between musculoskeletal pain with social isolation and loneliness: analysis of the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. Br J Pain. 2019;13:82–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hämmig O Health risks associated with social isolation in general and in young, middle and old age. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0219663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thomas NE, Williams DR. Inflammatory factors, physical activity, and physical fitness in young people. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2008;18:543–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alienist & Rockologist. Corona-marigold [short guide to managing uncertainty during confinement] [Internet]. 2020. [cited 2020 Apr 6]. Available from: https://igorthiriez.com/portfolio/le-corona-souci-petit-guide-de-gestion-de-lincertitude-enperiode-de-confinement/

- 19.Pontvert C The corona-worry. In: Twitter [Internet]. 2020. Mar 25 [cited 2020 Apr 6]. Available from: https://twitter.com/caropontvert/status/1242843650679324673

- 20.Mizumoto K, Yamamoto T, Nishiura H. Contact behaviour of children and parental employment behaviour during school closures against the pandemic influenza A (H1N1–2009) in Japan. J Int Med Res. 2013;41:716–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]