The long-acting complement inhibitor ravulizumab has recently been approved for the treatment of patients with paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH) in first line or after treatment with eculizumab.1–3 The trials investigating efficacy of ravulizumab demonstrated noninferiority compared to eculizumab.2,3 Thus the indication for changing to ravulizumab is mainly related to quality of life and economization of healthcare due to less frequent dosing. However, no recommendations regarding the switch of patients requiring more than the standard dose of eculizumab to ravulizumab are available, as these patients had been excluded from clinical trials.3 We report on a 48 year-old male who was diagnosed with PNH in 1994. When we offered eculizumab for treatment, the patient declined due to the frequent hospital visits associated with eculizumab administration. In 2014, his general condition suddenly worsened, and he suffered from severe abdominal pain. The lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) level was 2191 U/l and the neutrophil granulocyte clone size amounted to 99%. A magnetic resonance tomography scan revealed Budd-Chiari syndrome and portal vein thrombosis together with splenomegaly and ascites. The patient agreed to eculizumab therapy and therapeutic anticoagulation with phenprocoumon. However, using the standard dose of eculizumab (900 mg every 2 weeks), no sufficient reduction of hemolysis could be achieved and the dose had to be increased stepwise to 1800 mg every two weeks.

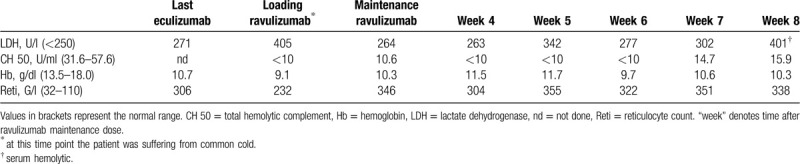

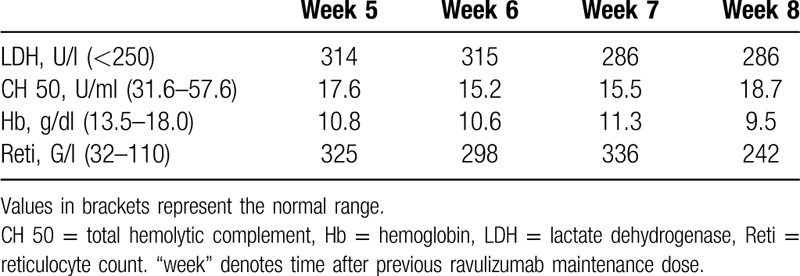

When ravulizumab was approved by health authorities, we discussed a switch to this long-lasting complement inhibitor and offered this treatment to our patient who consented. The standard procedure to switch from eculizumab to ravulizumab for a patient weighing 80 kg (as the patient described here) consists of a loading dose of 2700 mg ravulizumab, followed by a maintenance dose of 3300 mg after 2 weeks and, thereafter, 3300 mg every 8 weeks.2,3 Due to the high dose of eculizumab required in our patient, an increased loading dose of 3300 mg, equivalent to the maintenance dose was chosen to ensure sufficient amounts of circulating antibodies upfront to avoid breakthrough hemolysis (BTH) between loading and first maintenance dose. On day one of ravulizumab therapy, the patient suffered from a common cold accompanied by mild hemolysis (LDH level 405 U/l). Two weeks later the common cold had resolved, LDH amounted to 264 U/l, and total hemolytic complement (CH50, determined using the auto kit CH50 assay (Fujifilm) on a Cobas C501 device by Roche) was 10.6 U/ml, suggesting adequate control of hemolysis and complement activity following the ravulizumab loading dose. We therefore continued and administered the first maintenance dose of ravulizumab with 3300 mg. Based on the dosing-regimen of eculizumab, we assumed that the weight-adjusted maintenance dose of 3300 mg ravulizumab should result in sufficient control of hemolysis for at least 4 weeks. We subsequently examined LDH, CH50 and blood counts 4 weeks after the first maintenance dose and thereafter every week (Table 1). To determine the optimal dosing-interval in our patient, we chose an increase of LDH to >1.5× the upper limit of normal (ULN) as trigger for next dosing. At week 8, the LDH exceeded this 1.5 × ULN threshold for the first time (Table 1) so that we administered the second maintenance dose of ravulizumab. To rule out the possibility that the relatively long dosing-interval was caused by a high concentration of circulating antibody following the increased loading dose, we continued to monitor LDH levels weekly (Table 2). Eight weeks after the second maintenance therapy no increase of LDH to >1.5 × ULN was found and therapy was again administered as planned. During the switch period, the patient did not develop BTH or other adverse events and is now on a stable regimen with the weight-adjusted dose of ravulizumab of 3300 mg every 8 weeks.

Table 1.

Laboratory Values During Switch From Eculizumab to Ravulizumab.

Table 2.

Laboratory Values During the Second “Cycle” of Ravulizumab

While eculizumab has led to a major improvement in survival and quality of life in patients with PNH,4 the necessity for frequent dosing (associated with hospital visits in many countries) as well as restrictions in holiday planning have kept some patients from starting potentially life-saving therapy. Indeed, our patient had initially declined complement inhibitor therapy despite being informed about the risk of untreated PNH5,6 and had accepted treatment only after a near fatal complication of the disease. Following the approval of ravulizumab in Europe in 2019, patients may switch from eculizumab to ravulizumab outside of clinical trials. Such a switch has been described in clinical trials for patients receiving the approved dose of eculizumab.2,3 In patients treated with eculizumab who have an insufficient response to this drug, either the dosage may be increased or the interval between the doses are shortened.4 However, no data exist on the modality and the dosing scheme for ravulizumab in patients requiring higher doses of eculizumab. In our patient sufficient control of hemolysis could only be achieved by doubling the standard dose of eculizumab. Potential risks associated with the switch from high-dose eculizumab to ravulizumab such as BTH, seemed acceptable and manageable due to continuous monitoring. Indeed, no BTH or other adverse events were recorded in our patient. An interesting observation was that a “standard” ravulizumab dosing-interval of 8 weeks was sufficient in a patient previously treated with a double standard dose of eculizumab. Even though previous clinical trials have shown that ravulizumab seems to be slightly more potent than eculizumab at standard dosing, no significant differences in LDH normalization, transfusion-frequency or BTH were observed.2,3 To determine whether an accumulation of antibody due to the loading dose might have contributed to the long interval in the first “cycle,” we repeated the LDH monitoring in a second “cycle,” but again no BTH occurred. One might also speculate that the disease activity in our patient could have abated spontaneously over time and even with a standard dose of eculizumab a satisfactory control of hemolysis might have been achieved at the time of switching to ravulizumab.

Together, switching our patient from higher than approved doses of eculizumab to ravulizumab was well-tolerated and control of hemolysis was achieved with the standard dose of ravulizumab. However, more patients and a longer observation time are required—preferably in a clinical trial—to define standards for the switch of PNH patients from high-dose eculizumab to ravulizumab.

Footnotes

Citation: Füreder W, Valent P. Switching from high-dose eculizumab to ravulizumab in paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria: a case report. HemaSphere, 2020;4:4:(e455). http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/HS9.0000000000000455

Author contributions: WF and PV analyzed the data and wrote the paper.

WF received honoraria from Alexion and Novartis.

PV received honoraria from Alexion, Celgene, Deciphera, Pfizer, Blueprint, Astellas, Incyte and Novartis.

References

- 1.Sheridan D, Yu ZX, Zhang Y, et al. Design and preclinical characterization of ALXN1210: a novel anti-C5 antibody with extended duration of action. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0195909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee JW, Sicre de Fontbrune F, Wong Lee L, et al. Ravulizumab (ALXN1210) vs eculizumab in adult patients with PNH naive to complement inhibitors: the 301 study. Blood. 2019;133:530–539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kulasekararaj AG, Hill A, Rottinghaus ST, et al. Ravulizumab (ALXN1210) vs eculizumab in C5-inhibitor-experienced adult patients with PNH: the 302 study. Blood. 2019;133:540–549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kelly RJ, Hill A, Arnold LM, et al. Long-term treatment with eculizumab in paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria: sustained efficacy and improved survival. Blood. 2011;117:6786–6792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hill A, Richards SJ, Hillmen P. Recent developments in the understanding and management of paroxysmal nocturnal haemoglobinuria. Br J Haematol. 2007;137:181–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hill A, Kelly RJ, Hillmen P. Thrombosis in paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria. Blood. 2013;121:4985–4996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]