Abstract

Hypokalemia of renal origin can arise from genetic abnormalities in a variety of transporters or channel proteins that mediate tubular handling of potassium. Recently, mutations in claudin 10 have been documented in patients with hypokalemia in association with a range of other electrolyte abnormalities and skin and sweat gland manifestations. Here, we report a 12-year old Hispanic boy who presented with anhydrosis, aptyalism, alacrima, hypokalemia, and hypocalciuria, in whom we detected a homozygous mutation in the claudin 10 gene. Over the 4-year follow-up period, he developed hypermagnesemia and a decline in eGFR to 59 ml/min/1.73 m2. His unaffected parents and siblings were heterozygous for the mutation. We summarize the clinical phenotype encountered in patients with claudin 10 mutations. It is characterized by significant heterogeneity in electrolyte and extrarenal abnormalities and it is associated with a risk of progressive loss of kidney function in up to 33% of cases. Awareness of this association between claudin 10 mutations and electrolyte abnormalities, namely, hypokalemia and hypermagnesemia, sheds new light on the physiology of potassium and magnesium handling along the nephron and increases the likelihood of identifying the underlying tubular mechanism in patients with newly-diagnosed hypokalemia with or without concomitant hypermagnesemia.

Keywords: claudin-10 (CLDN10), hypokalemia, hypermagnesemia, anhydrosis, aptyalism, alacrima, genetic disease, kidney function, whole-exome sequencing, mutation detection, tight juntion, paracellular transport, case report

INTRODUCTION

Renal causes of hypokalemia include conditions associated with increased urine flow rate or alterations in the transepithelial membrane potential (1). If these disturbances are excluded, then an intrinsic tubular defect in potassium handling is likely. In pediatric patients, the most common tubulopathies associated with hypokalemia are Bartter, Gitelman, and EAST (epilepsy, ataxia, sensorineural deafness, and salt-wasting renal tubulopathy) syndromes (2). These disorders cause metabolic alkalosis and hypokalemia, attributable, respectively, to genetic mutations in the sodium/potassium/chloride cotransporter in the medullary thick ascending limb, the sodium/chloride cotransporter in the distal convoluted tubule, and KCNJ10, an inwardly rectifying potassium channel in the distal convoluted tubule (2).

However, there are patients with hypokalemia with no identifiable mutation in these transport proteins. We report a boy who presented with reduced sweating, saliva production, and lacrimation and subsequently hypokalemia. Using whole-exome sequencing, we identified a mutation in the claudin 10 gene (CLDN10) that has recently been reported to be associated with hypokalemia, hypermagnesemia, and abnormal dermatological findings (3,4,5). The features in our case broaden the spectrum of disease presentations associated with mutations in CLDN10.

CASE REPORT

A 12-year-old Hispanic boy with obesity was referred for evaluation of hypokalemia. He had been followed since age 17 months in the Dysautonomia Center for anhydrosis, aptyalism, and alacrima. The family immigrated to the United States from Ecuador. There was no family history of renal disease or tubular dysfunction. However, the mother and father are first cousins.

At the initial evaluation, he had polyuria but no lightheadedness, syncope, muscle cramps, or salt craving. Physical examination included height at 25th percentile, BMI of 33 kg/m2, normal blood pressure, and no edema. The skin was normal in color and thickness and not scaly. There was no rash, vesicles, pustules, or ichthyosis. His potassium concentration was 2.7 mmol/L and he was placed on potassium chloride 10 mmol orally twice daily (0.3 mmol per kilogram of body weight per day). Additional testing demonstrated hypochloremia, hyporeninemia, hyperaldosteronism, and hypercholesterolemia. His serum creatinine concentration was normal, at 0.61 mg/dl.

The hypokalemia persisted and the potassium chloride dose was increased to 30 mmol orally twice daily (0.6 mmol/kg per day). He continued to have polydipsia and polyuria, though the latter gradually improved. During follow-up, he developed hypermagnesemia and a decline in eGFR from 101 at baseline to 59 ml/min/1.73 m2. He had no hypertension or proteinuria, and with a genetic basis for his disease, a kidney biopsy was not performed because it was unlikely to provide information that would influence his management.

At his most recent evaluation, he is generally well although his hypokalemia remains difficult to control, with a potassium concentration of 3.1 mmol/L. His kidneys are normal in size without nephrocalcinosis.

Additional Investigations

Whole-exome sequencing was performed (detailed methods provided in Item S1) and identified homozygous mutations in CLDN10, ANXA5 (encoding annexin V), and FUT2 (encoding fucosyltransferase 2). The mutation in CLDN10 is absent in the Exome Aggregation Consortium (ExAC)5a and NHLBI GO Exome Sequencing Project5b databases, is highly conserved amongst paralogs and homologs of the CLDN10 protein, and PolyPhen and SIFT predictions5c suggest it is deleterious. The FUT2 mutation is present in 8 Latino individuals in the ExAC database, with 1 individual homozygous for the mutation. Mutations in FUT2 are associated with microbial diversity in the colonic mucosa. The mutation in ANXA5 is not present in the ExAC database and mutations in this gene are associated with recurrent pregnancy loss. CLDN10 was the best possible candidate gene based on its function in the kidney, its expression pattern, and the fact that mutations in CLDN16 and CLDN19 cause hypomagnesemia. The CLDN10 mutation, at chr13:96212403:A>G, is predicted to lead to a substitution of a glycine for an arginine at a residue highly conserved across species and CLDN isoforms (position 78 in claudin 10 isoform a, so denoted here as R78G).

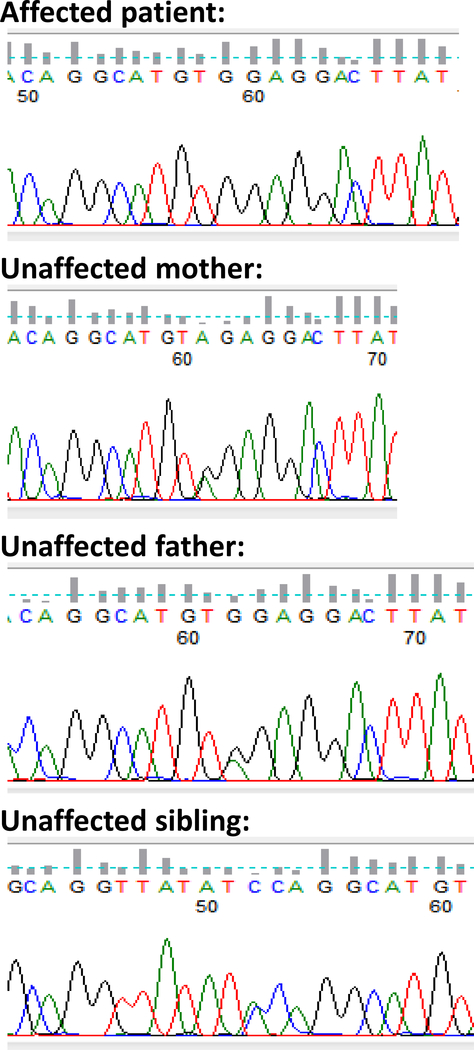

Polymerase chain reaction amplification and direct Sanger sequencing of CLDN10 in the affected child, unaffected parents, sister, brother, and maternal uncle revealed the homozygous R78G mutation only in the affected child, and the heterozygous mutation in both parents, unaffected siblings, and unaffected maternal uncle (Figure 1). This solidifies the proposition that the homozygous R78G mutation in CLDN10 is the cause of the condition in this kindred.

Figure 1.

chromatograms showing results of direct sequencing.

DISCUSSION

We describe an boy who initially presented with anhydrosis, alacrima, and hypokalemia. He later developed hypermagnesemia and a decline in eGFR to CKD stage 3. Genetic testing revealed a homozygous mutation in CLDN10, a gene implicated in the pathogenesis of hypermagnesemia. This case highlights the role of CLDN10 in the regulation of serum potassium and magnesium levels and the potential adverse long-term consequences of this mutation.

Claudins are proteins that are components of tight junctions and serve as regulators of paracellular transport along the nephron (6,7). They can act as either barriers that seal the paracellular space or pores permitting selective movement of small ions and water (7,8). Claudins associate with one another in interactions that can involve different claudin isoforms, and can occur in cis (within the same cell plasma membrane) or in trans (between adjacent cell plasma membranes) (9,10).

The unique pattern of claudin subtype expression underlies the properties and function of each specific nephron segment (6,9,10). In the proximal tubule, CLDN2 and CLDN10 isoform a contribute to bulk reabsorption of salt and water. The thick ascending limb is enriched with CLDN16 and CLDN19, which facilitate reabsorption of calcium and magnesium (6). CLDN4 and CLDN8 support chloride transport in the distal nephron and indirectly enable electrogenic sodium reabsorption (6).

Given the integral role of claudins in the kidney, it is not surprising that defects in these proteins are implicated in the pathogenesis of several renal diseases. Pathogenic mutations in CLDN16 or CLDN19 result in familial hypomagnesemia with hypercalciuria and nephrocalcinosis, and end-stage kidney disease in most patients. Genetic variants in CLDN14 have been associated with a greater risk of nephrolithiasis (6,7).

Mice lacking claudin 10 present with hypermagnesemia and interstitial nephrocalcinosis. Most recently, pathogenic mutations in CLDN10 have been linked clinically to hypokalemia with metabolic alkalosis. The original article from Klar et al described 13 affected individuals from 2 distantly related Pakistani families who presented with anhydrosis and heat intolerance.3 Six patients were intensively studied and found to have a missense mutation in CLDN10 isoform b. None of the patients had hypokalemia but all 6 had hypermagnesemia. Three individuals with available laboratory data had eGFR in the range 71–74 ml/min/1.73 m2 (CKD Stage 2). The second report from Bongers et al involved two patients who presented with hypokalemia, normal serum magnesium levels, urine concentrating defect, and hypocalciuria.4 There was variable expression of the mutant protein, with reduced levels in the tight junction in one case. Neither patient had any reported dermatological abnormalities. In the third report from Hadj-Rabia et al of 6 cases linking CLDN10 mutations and hypokalemia, the authors coined a novel disease entity, HELIX syndrome, characterized by hypohydrosis, electrolyte abnormalities, lacrimal gland dysfunction, icthyosis, and xerostomia.5 Hypermagnesemia was documented in 5 out of 6 cases.

Based on in vitro studies, mutant CLDN10 channels retain selective permeability for cations over anions but are less permeable to sodium (3). The increased sodium concentration in the tubular fluid enhances the electrical gradient supporting magnesium reabsorption. In addition, there is altered interaction with CLDN16 and CLDN19, resulting in hypermagnesemia. The increased delivery of sodium to the aldosteronesensitive portions of the distal tubule and collecting duct promotes increased potassium secretion and hypokalemia.

Table 1 summarizes the variable clinical features of patients with a documented CLDN10 mutation. Hypohydrosis and lacrimal duct dysfunction were noted in 13 cases, hypokalemia in 6/15 (40%), hypermagnesemia in 12/15 (80%), and hypocalciuria in all cases. Three patients, including our patient, had polyuria, indicating that the altered tubular function may have disrupted the medullary gradient or responsiveness to vasopressin, and impaired the urinary concentration capacity. Importantly, 4/12 patients for whom information was available showed a decline in eGFR, indicating that the syndrome is not benign. The cause of the decline in eGFR requires further study, but this may be related to hypokalemia-induced interstitial inflammation, vasoconstriction, and increased fibrosis (11,12,13). The phenotypic heterogeneity may reflect the degree of involvement of the two CLDN10 isoforms, other genetic modifiers, or differences in dietary intake of potassium, magnesium, and other electrolytes.

Table 1.

Clinical summary of cases with documented claudin 10 mutations

| Bongers et al4 | Hadj-Rabia et al5 | Klar et al3,1 | This Report | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pt 1 | Pt 2 | Pt 1 | Pt 2 | Pt 3 | Pt 4 | Pt 5 | Pt 6 | Pt 1 | Pt 2 | Pt 3 | Pt 4 | Pt 5 | Pt 6 | ||

| Age at presentation, y | 21 | 15 | 21 | 14 | 6.5 | 4.5 | 46 | 6 | 47 | 27 | 25 | 23 | 27 | 35 | 12 |

| Gender | F | M | M | F | F | F | M | M | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | M |

| Hypokalemia | Y | Y | Y2 | Y2 | N2 | N2 | Y2 | N2 | N | N | N | N | N | N | Y1 |

| Hypermagnesemia | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y |

| Hypocalciuria3 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | NR | Y |

| Extrarenal symptoms | Hypohidrosis, lacrimal gland dysfunction, ichthyosis, xerostomia | Hypohidrosis, lacrimal gland dysfunction, xerostomia | Hypohidrosis, lacrimal gland dysfunction, xerostomia | ||||||||||||

| Reduced eGFR4 | Y | N | N | N | N | Y | Y | N | NR | N | NR | NR | N | N | Y |

| Identified CLDN10 Mutation | c.446C>G & c.465–1G>A5 |

c.446C>G & c.217G>A6 |

Pts 1–4: c.386C>T8 & c.392C>T9; pts 5–6: c.2T>C7,9 |

c.144C>G7,9 | R78G5,7 | ||||||||||

There were 13 total patients in study, but authors only reported more extensive phenotypes for these 6

The diagnosis of hypokalemia was made in the presence of oral potassium supplementation

Bongers et al and Hadj-Rabia et al results based on 24-hour urine collection; Klar et al and our case based on urine spot samples

eGFR < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2; calculated by Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) equation in adults and the Schwartz formula in children

These two mutations affect both major Claudin 10 isoforms (a and b)

First listed mutation affects both isoform a and b; second listed mutation only affects isoform b

Homozygous mutations

Isoform a

isoform b

NR, not reported; pt, patient; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; CLDN10, claudin 10 gene; c, coding DNA

Our case is one of the youngest patients with hypokalemia in whom a CLDN10 mutation has been documented. The reduction in eGFR at this age suggests more severe kidney injury, compared to the other patients of similar age. Our patient resembles the patients described by Hadj-Rabi et al and Klar et al, who had abnormalities in the skin, mucous membrane, and hypermagnesemia. The absence of hypermagnesemia at initial presentation may reflect changes in diet intake of sodium and/or magnesium or an agedependent effect on the interaction of the mutant CLDN10 with other CLDN isoforms. However, similar to the patients described by Bongers et al, our patient had hypocalciuria, which initially suggested a diagnosis of Gitelman syndrome.

In conclusion, awareness of the association between CLDN10 mutations and hypokalemia and hypermagnesemia sheds new light on the physiology of potassium and magnesium handling along the nephron and increases the likelihood of identifying the underlying tubular mechanism in patients with newly-diagnosed disturbances in serum potassium or magnesium levels. We suggest testing for CLDN10 mutations in patients with hypokalemia or hypermagnesemia in conjunction with dermatological abnormalities or if testing for genes known to be associated with abnormal serum magnesium or potassium concentration is negative.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Support: This work was supported in part by grant NIDDK RO1100307 (HT).

Footnotes

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Item S1. Detailed methods.

Supplementary Material Descriptive Text for Online Delivery Supplementary Figure S1 (PDF). Detailed methods.

Financial Disclosure: The authors declare that they have no relevant financial interests.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Weiner ID, Wingo CS. Hypokalemia--consequences, causes, and correction. J Am Soc Nephrol 1997;8(7):1179–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kleta R, Bockenhauer D. Salt-Losing Tubulopathies in Children: What’s New, What’s Controversial? J Am Soc Nephrol 2018; 29(3):727–739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Klar J, Piontek J, Milatz S, Tariq M, Jameel M, Breiderhoff T, Schuster J, Fatima A, Asif M, Sher M, Mäbert K, Fromm A, Baig SM, Günzel D, Dahl N. Altered paracellular cation permeability due to a rare CLDN10B variant causes anhidrosis and kidney damage. PLoS Genet 2017;13(7):e1006897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bongers EMHF, Shelton LM, Milatz S, Verkaart S, Bech AP, Schoots J, Cornelissen EAM, Bleich M, Hoenderop JGJ, Wetzels JFM, Lugtenberg D, Nijenhuis T. A Novel Hypokalemic-Alkalotic Salt-Losing Tubulopathy in Patients with CLDN10 Mutations. J Am Soc Nephrol 2017;28(10):3118–3128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hadj-Rabia S, Brideau G, Al-Sarraj Y, Maroun RC, Figueres ML, Leclerc-Mercier S, Olinger E, Baron S, Chaussain C, Nochy D, Taha RZ, Knebelmann B, Joshi V, Curmi PA, Kambouris M, Vargas-Poussou R, Bodemer C, Devuyst O, Houillier P, El-Shanti H. Multiplex epithelium dysfunction due to CLDN10 mutation: the HELIX syndrome. Genet Med 2018;20(2):190–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yu ASL. Claudins and the Kidney. J Am Soc Nephrol 2015;26(1):11–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Olinger E, Houillier P, Devuyst O. Claudins: a tale of interactions in the thick ascending limb. Kidney International 2018;93(3):535–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fromm M, Piontek J, Rosenthal R, Gunzel D, Krug SM. Tight junctions of the proximal tubule and their channel proteins. Pflugers Arch Eur J Physiol 2017;469(78):877–887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Muto S Physiological roles of claudins in kidney tubule paracellular transport. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 2017;312(1):F9–F24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gong Y, Hou J. Claudins in barrier and transport function—the kidney. Pflugers Arch Eur J Physiol 2017;469(1):105–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tolins JP, Hostetter MK, Hostetter TH. Hypokalemic nephropathy in the rat. Role of ammonia in chronic tubular injury. J Clin Invest 1987;79(5):1447–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ray PE, Suga S, Liu XH, Huang X, Johnson RJ. Chronic potassium depletion induces renal injury, salt sensitivity, and hypertension in young rats. Kidney Int 2001;59(5):18508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Suga S, Phillips MI, Ray PE, Raleigh JA, Vio CP, Kim YG, Mazzali M, Gordon KL, Hughes J, Johnson RJ. Hypokalemia induces renal injury and alterations in vasoactive mediators that favor salt sensitivity. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 2001;281(4):F620–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5a.Lek M, Karczewski KJ, Minikel EV, Samocha KE, Banks E, Fennell T, O’Donnell-Luria AH, Ware JS, Hill AJ, Cummings BB, Tukiainen T, Birnbaum DP, Kosmicki JA, Duncan LE, Estrada K, Zhao F, Zou J, Pierce-Hoffman E, Berghout J, Cooper DN, Deflaux N, DePristo M, Do R, Flannick J, Fromer M, Gauthier L, Goldstein J, Gupta N, Howrigan D, Kiezun A, Kurki MI, Moonshine AL, Natarajan P, Orozco L, Peloso GM, Poplin R, Rivas MA, Ruano-Rubio V, Rose SA, Ruderfer DM, Shakir K, Stenson PD, Stevens C, Thomas BP, Tiao G, Tusie-Luna MT, Weisburd B, Won HH, Yu D, Altshuler DM, Ardissino D, Boehnke M, Danesh J, Donnelly S, Elosua R, Florez JC, Gabriel SB, Getz G, Glatt SJ, Hultman CM, Kathiresan S, Laakso M, McCarroll S, McCarthy MI, McGovern D, McPherson R, Neale BM, Palotie A, Purcell SM, Saleheen D, Scharf JM, Sklar P, Sullivan PF, Tuomilehto J, Tsuang MT, Watkins HC, Wilson JG, Daly MJ, MacArthur DG; Exome Aggregation Consortium. Analysis of protein-coding genetic variation in 60,706 humans. Nature. 2016. August 18;536(7616):285–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5b.Exome Variant Server, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grand Opportunity Exome Sequencing Project (NHLBI GO ESP), Seattle, WA (URL: http://evs.gs.washington.edu/EVS/) [date (month, yr) accessed].

- 5c.Choi Y, Sims GE, Murphy S, Miller JR, Chan AP. Predicting the functional effect of amino acid substitutions and indels. PLoS One. 2012;7(10):e46688. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.