Abstract

Background:

Emergency department (ED) visits are critical events for older adults, but little is known regarding their experiences, particularly about their physical needs, the involvement of accompanying family members, and the transition back to the community.

Objective:

To explore experiences of an ED visit among patients aged 75 and older.

Methods:

In a mixed-methods study, a cohort of patients aged 75 and older (or a family member) discharged from the ED back to the community was recruited from 4 urban EDs. A week following discharge, structured telephone interviews supplemented with open-ended questions were conducted. A subsample (76 patients, 32 family members) was purposefully selected. Verbatim transcripts of responses to the open-ended questions were thematically analyzed.

Results:

Experiences related to physical needs included comfort, equipment supporting mobility and autonomy, help when needed, and access to drink and food. Family members required opportunities to provide patient support and greater involvement in their care. At discharge, patients/families required adequate discharge education, resolution of their health problem, information on medications, and greater certainty about planned follow-up medical and home care services.

Conclusions:

Our findings suggest several areas that could be targeted to improve patient and family perceptions of the care at an ED visit.

Keywords: older adults, emergency medicine, patient experiences, family, transitional care

Introduction

Emergency department (ED) visits are critical events for older adults who often present with complex physical health problems, functional, and often cognitive impairment (1). Senior Friendly Hospital Initiatives (SFHI) (2) and geriatric ED guidelines (3) recommend protocols identifying and assessing those at risk of functional decline and other adverse outcomes after discharge, connecting with homecare and medical services in the community, and adapting the ED environment to their needs. As such, understanding both patient and family experiences of ED care can inform quality improvement initiatives (4) as older patients are usually accompanied by family members or friends who play an important role in their care (5).

A review of qualitative studies and surveys addressing older patients’ perceptions of ED care identified several domains of experiences (6). Among these domains, those that are common to all age groups, that is, interpersonal attributes of care, waiting times, and communication, have been studied (7,8). However, domains that are more relevant to older adults, that is, physical needs, the needs of family members, and transitional care needs, have been less fully investigated (6).

Previous studies have mostly focused on ED experiences of older patients with specific conditions, for example, living with chronic diseases (9), receiving end-of-life care, or admitted to hospital from ED (10 -13). Few studies involving small samples, however, have investigated ED care and postdischarge experiences among older patients returning to their original residence after an ED visit (14,15). This vulnerable population, known to be at increased risk of functional decline (16), merits further attention. In addition, family members’ experiences have seldom been taken into account (5,17). Moreover, patient interviews were usually conducted either during the ED visit (18,19), which would give incomplete information on transitional care, or 6 to 12 months following the ED visit (9,17,20), which might have led to recall bias.

Rationale for the Study

This study was conducted in the context of a multisite project. A previous quantitative phase involved the development of experience measures among older patients discharged to the community from the ED (21). The current report, using a qualitative descriptive approach (22), aims to describe the lived experiences of ED care and discharge processes among patients 75 years and older (or their family members) discharged to their original residence with a particular focus on those domains that are more relevant to older patients.

Method

Setting

We selected 4 university-affiliated EDs in 2 cities based on the results of a 2013/14 survey of elder friendly care at 76 Quebec EDs (23). Taking into account the feasibility of allocating research staff, we limited the EDs for this study to those located in Montreal and Quebec City (2 EDs in each). In a series of meeting with study partners (experts in geriatric ED care across Canada) and members of the research team, the results of the survey were used to select 4 EDs that were similar in size, staffing, and volume of visits of patients aged 75 and older, but with different patterns of implementation of geriatric ED services (3). Appendix A shows the key characteristics of 4 EDs. Institutional research ethics boards of all participating hospitals approved the study protocol.

Sample

A cohort of patients aged 75 and older discharged to their original residence (own home, residence, nursing home) was recruited from July 2014 to February 2016. We targeted patients aged 75 or older since this age group reflects a higher prevalence of frailty and is often the recommended cut point for the delivery of geriatric services such as the SFHI in Quebec (24). During weekday work hours, 3 trained research assistants (RAs) identified patients aged 75 years and older in ED clinical registries. They approached all ambulatory (walk-in or waiting room) patients; these patients are less likely to be admitted and mostly discharged home. Patients who are placed on ED beds (locally termed stretchers) are either acutely ill or cannot tolerate staying seated and often expected to be admitted to hospital. RAs approached bed patients only if they were expected to be discharged back to their original residence according to ED clinical staff. An accompanying proxy (family member or friend) was invited to participate if a patient was too ill, cognitively impaired, or not able to communicate in English or French (judged by ED clinical staff, families, and RAs). Eligibility criteria for proxies were ability to answer questions in English or French, residence in the province of Quebec, and reachable by telephone after the ED discharge. Potentially eligible patients or proxies signed informed consent forms and completed a face-to-face baseline questionnaire in the ED. This questionnaire included language spoken at home, country of birth, living arrangements, marital status, years of education, and the Identification of Seniors at Risk screening questionnaire for functional decline (25).

RAs recruited patients systematically from ED logs and balanced the number of ED bed with ambulatory patients. At the time of recruitment, it was often not known whether or not a bed patient would be admitted. Patients became eligible once the discharge was confirmed in ED registries. Patients admitted to hospital were excluded. This process was designed to allow the recruitment of patients whose discharges were confirmed during out of work hours or weekends. Some information on ED visits was retrieved from ED registries: patient sex, age, autonomy code (ambulatory vs bed), the Canadian Triage and Acuity Scale (immediate to urgent [scores 1-3] vs less urgent to nonurgent [scores 4-5]) (26), and dates and times of arrival and discharge.

Follow-up interviews

RAs conducted telephone interviews with participants 1 week after discharge and administered a structured questionnaire comprising 26 items representing potential problematic experiences (21).

The telephone survey included open-ended questions to explore in-depth the lived experiences of the ED care and discharge processes and to identify other experiences not covered by the questionnaire. Both patients and families were asked the same questions, with minor adjustments to family members (Appendix B). A purposive subsample of participants, who provided in-depth feedback to those open-ended questions and were judged by the RAs to have introspection (27), was flagged for the qualitative analysis. Termination of data collection was not based on data saturation (redundancy) by design, and analysis took place after data collection was completed (28). The same RA recruited and conducted the interview with each participant, which established a priori social contact between the interviewers and participants.

Analysis

We compared the characteristics of the ED visits and patient demographics in our purposeful subsample and to those who were not selected for the qualitative analysis, using χ2 tests (29) with the significance level at .05. The analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4.

Qualitative segments of tape-recorded interviews, lasting 5 to 15 minutes, were transcribed verbatim. D.C-S. examined the quality of the de-identified transcripts and stored them in QDA Miner 4.0 software. We used a hybrid approach, deductive–inductive thematic analysis (30), whereby the data were mainly analyzed in the light of predetermined 3 domains of experiences considered to be more relevant to older patients (physical needs, the needs of family members, transitional care needs) in the literature (6) (deductive). Domains of experiences that are common to all age groups (interpersonal attributes of care, communication, waiting times), and other patterns inductively emerging from the data (e.g., appreciation of ED care) were also analyzed, but not reported in this paper.

Comparisons within each interview and between different interviews were conducted as follows: (a) 2 bilingual coders (D.C-S. and one study RA with expertise in qualitative research) independently coded the first 25 transcripts and developed a preliminary codebook; (b) D.C-S. coded the remaining transcripts using the preliminary codebook and updated the codebook; (c) using the updated codebook, the RA independently coded 30 randomly selected transcripts from the remaining transcripts (the software determined 94% agreement), the 2 coders discussed disagreements until reaching consensus, and (d) the main findings were further validated with other 2 team members (F.D. and J.M.) and illustrated with quotes. We believe that we reached data saturation with the subsample included in the analysis since there were no more emerging patterns in the data after coding about two-thirds of the transcripts.

Results

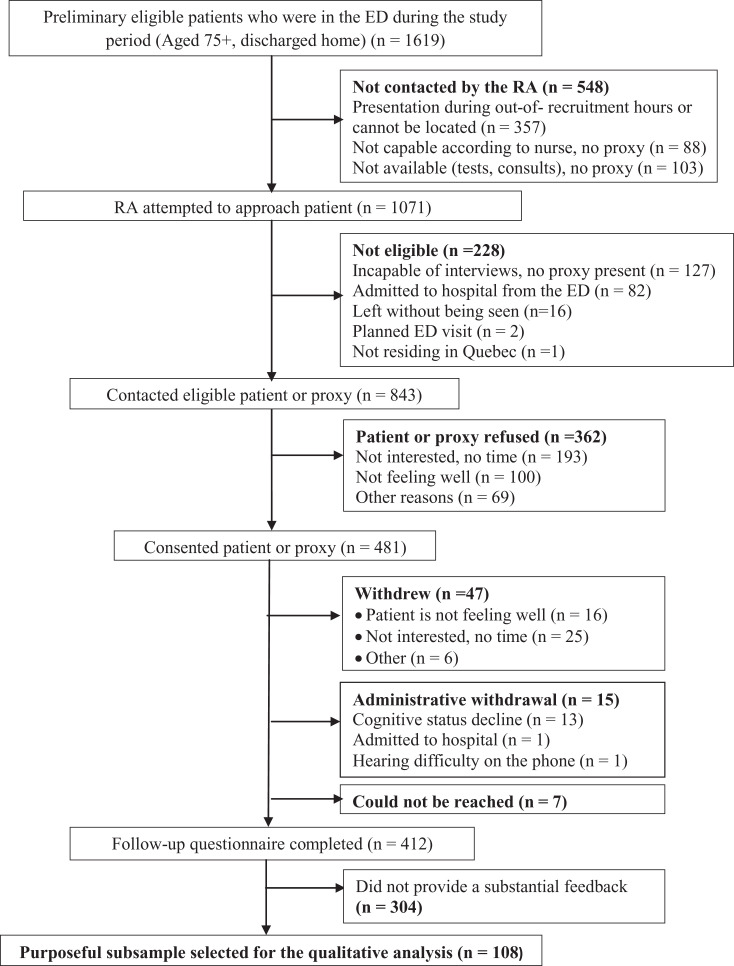

Of 843 eligible patients contacted in the ED by an RA, 481 (57%) patients or their proxies provided written consent. Of the 481 who consented, 412 (85.6%) completed the 1-week interview (Figure 1). Among 108 selected participants, 32 family members (26 children, 5 spouses, and 1 friend) completed the interviews on behalf of patients. Table 1 shows baseline patient characteristics in the larger cohort, comparing the purposeful subsample selected for the qualitative analysis to the sample including those excluded. Both groups were similar in general, although the subsample was more highly educated than those excluded.

Figure 1.

Recruitment flow chart in 4 emergency departments.

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics.a

| Data Sources and Variables | Purposeful Subsample for Qualitative Analysis, n = 108 | Remaining Sample With No Substantial Feedback, n = 304 | χ2, P Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Emergency department registry data | |||||

| Female | 77 | 71.3 | 198 | 65.1 | .243 |

| Age group | .445 | ||||

| 75-84 | 67 | 62.0 | 201 | 66.1 | |

| 85+ | 41 | 38.0 | 103 | 33.9 | |

| Autonomy status | .451 | ||||

| Bedside | 53 | 49.1 | 162 | 53.3 | |

| Ambulatory | 55 | 50.9 | 142 | 46.7 | |

| Triage code | .967 | ||||

| Immediate (1) to urgent (3)b | 47 | 43.5 | 133 | 43.8 | |

| Less urgent (4) to nonurgent (5) | 61 | 56.5 | 171 | 56.3 | |

| Emergency department length of stay | .092 | ||||

| <12 hours | 78 | 72.2 | 192 | 63.2 | |

| 12-24 hours | 16 | 14.8 | 76 | 25.0 | |

| >24 hours | 14 | 13.0 | 36 | 11.8 | |

| Baseline interview | |||||

| Language spoken at home | .739 | ||||

| French | 90 | 83.3 | 249 | 81.9 | |

| English | 18 | 16.7 | 55 | 18.1 | |

| Born in Canada | 86 | 79.6 | 251 | 82.6 | .497 |

| Living arrangement | .080 | ||||

| Home | 65 | 60.2 | 211 | 69.4 | |

| Otherc | 43 | 39.8 | 93 | 30.6 | |

| Marital status | .089 | ||||

| Married/common-law | 46 | 42.6 | 142 | 47.0 | |

| Widowed | 32 | 29.6 | 106 | 35.1 | |

| Separated/divorced/single | 30 | 27.8 | 54 | 17.9 | |

| (missing) | (0) | (2) | |||

| Years of education completed | .029 | ||||

| 0-6 (some elementary school) | 19 | 17.8 | 37 | 12.3 | |

| 7-11 (completed some high school) | 30 | 28.0 | 127 | 42.2 | |

| 12+ (completed high school) | 58 | 54.2 | 137 | 45.5 | |

| (missing) | (1) | (3) | |||

| High-risk for functional decline (ISAR score 2+) | 48 | 44.4 | 137 | 45.1 | .911 |

Abbreviation: ISAR, Identification of Seniors at Risk, Bold value indicates the significance at the alpha level of 0.05.

a n = 412.

b Immediate (1) (n = 2), very urgent (15 minutes; 2) (n = 25).

c Senior residence, nursing home, or rehabilitation center.

Emerging subthemes categorized under the 3 domains are described in detail below, in descending order, from most to least frequent for a given domain, with illustrative verbatim extracts from the transcripts. Additional representative quotes are provided in Table 2. Since patient and family perspectives were comparable in general, we report overall experiences without stratification by informant.

Table 2.

Summary of Thematic Analysis Findings and Illustrative Quotes.a

| Domain of Experience | Positive Experiences | Negative Experiences |

|---|---|---|

| Domain 1: Older patients’ physical needs | ||

| Comfort | It was her [staff] who told me, who arranged the nice armchair. She covered it with blankets, and put me on the chair, and then brought me a nice warm blanket to put around my shoulders. This was the moment I appreciated the most | You know, the lady next to me was snoring…And each time they opened the curtain, closed the curtain [separating beds]…you couldn’t sleep peacefully |

| Equipment supporting mobility and autonomy | Since I felt sort of well and since I was going to spend quite some time in the emergency, I said: “I am going to sit down,” and I had a nice rocking chair | There was no footstool to get on the bed. I couldn’t get back on the bed by myself. I had to climb on the bed |

| Help when needed | I went to the bathroom. He [staff] came help me open and close the door. He told me to ring when I was done. When I came out, there was a woman in the aisle, and she washed my hands and everything. I found it very good | I didn’t ask anything, but what I didn’t like was that no one came to help me remove my clothes to put on the hospital gown |

| Access to drink and food | And, other thing that I observed, the meal was correct, it was even good, I can say that | She hadn’t eaten for the entire day. I thought they had given her food at the emergency department, but they didn’t give her anything. It was 9 pm, and she was mad because she had not eaten |

| Domain 2: The needs of family members | ||

| ED care practices and policies involving families | My dad could be a good example of someone arriving with severe anxiety. In this case like this, I took care of this aspect. I was there, I talked to him, I calmed him down | It’s true that there is a surveillance for 5 minutes every half an hour [allowing family to see the patient], that I understand, but in the case of a person who has Alzheimer’s, I often find that it is a constraint because she [mother] might need me to be next to her |

| Space for family beside patients | We were able to be present there all the time. I was able to stay with my dad, and I was saying to myself I’m not privileged because sometimes I would look at the neighboring rooms and it was the same thing | You know, you keep asking him to climb on a stupid bed. The room is barely a closet, so even if you want to assist him to get on the bed, you can’t |

| Domain 3: Transitional care needs | ||

| Discharge information | I would say all, the reception, the staff, everything there, was very very very well orchestrated. It’s excellent what I was given as advice and for follow-up especially. I learned to do everything | Regarding the discharge, I left the same way I arrived, you know. No one said good bye, and I left. My grandson came to get me, and we left. There was nothing. There was no one even came to ask me whether I had any questions. It was over, you know. Let’s go |

| Resolution of health problems | We are very happy, very satisfied. My father is doing better, and I think the medical protocol has been followed very meticulously. Urinary problem is a minor problem but it gives major pain sensations, which is very uncomfortable. We were listened to well. We have to admit that my human experience went very well with my father in this context | Well, we came back in the middle of the night. I had an intense pain crisis here and there and became worried because we didn’t really know what was going on. So, we called the ambulance. I told [family member]: “we need to return to…” I felt like I had to return to the emergency, rather the hospital. So, the ambulance came to get me |

| Plans for further medical care | Doctor wanted to speak to the gastroenterologist before my mother leaves, and she had the blood tests results to receive and she gave them to us. It was reassuring, and we knew that we would have the follow-up the next day afternoon | I don’t know if she [emergency clerk] will call me to set up the appointment or if the rheumatologist office will, I don’t know. I am missing some information, but I didn’t receive any paper or prescription |

| Medication | The 2 pills [given at the emergency before leaving], one for the evening and one for the morning…This is excellent; it certainly helps a lot, especially late at night. The drug stores were closed since maybe 9, 10 o’clock. That helped me a lot | They contradicted the 2 doctors…one who said “you have a cyst behind, but you have to stop the Coumadin and then we will operate you…And then the other said: no, no, no, we must not stop, we must not stop the Coumadin, it must continue. So, that’s it, they both contradicted each other |

| Safe transport | One gentleman took me down to the door where the ambulances are and showed me where the phone was to phone for a taxi. And he came down with me to show me all that, which is good because I would have never thought of going that way | After being discharged from the emergency department, I found that I had to figure things out myself. The exit, I didn’t know where it was. I had to inform myself, talk to people, and find the exit, take a cab to get back home. The thing is when you get there, you are by yourself, you’re here for the first time. It isn’t obvious |

| Home care services | So, the [community health center] nurse had to come back in order to give her blood thinner and clean her wound | I’d have to find another place too. I do not have the energy, you know, to take care of it, and you have to go visit [places] you know…I need someone to do some of the shopping |

Abbreviation: ED, emergency department.

a Subthemes under each domain were tabulated in descending order, from most to least frequent for a given domain.

Domain 1: Older Patients’ Physical Needs

This theme was defined as the most basic of all older patients’ needs while staying in the ED, having to do with physical survival and autonomy. It encompassed the following 4 subthemes: comfort, equipment supporting mobility and autonomy, help when needed, and access to drink and food.

Comfort

Many participants expressed the lack of elements such as dimmed lights and silence at night enabling them to sleep. Many requested adjustments to room temperature and the provision of an extra blanket when needed.

The ceiling lights could have different settings…if the person is completely lying on their back, she always has those lights in her eyes. P42_ED3_translated

We ask for a blanket, they tell us that they have no budget. It was my daughter who brought me a blanket. I was freezing, shivering…P44_ED4_translated

Equipment supporting mobility and autonomy

The availability of the equipment needed to maintain mobility and autonomy, such as wheelchairs and walkers or other specific equipment in the washrooms, was reported to be essential by many participants.

Listen, to be able to take off clothes in the bathroom comfortably, it’s not easy. There’s no chair, there’s no bar to hold on to, there’s nothing. P87_ED2_translated

Help when needed

Participants also appreciated receiving help when they needed, specifically for going to the bathroom, putting their clothes on, getting onto high beds, or calling their families. Receiving help was critically important for patients with mobility problems.

I am disabled; I am waiting for hip surgery. I have a lot of back pain, and I have difficulty moving around. And she told me: “Go to the bathroom over there. Go to the bathroom.” So I went to the bathroom. I had [intravenous] perfusion. P38_ED3_translated

Access to Drink and Food

Access to drink and food when thirsty or hungry was vital for some participants.

Well the only thing that I really minded, and I was there quite a long time before I found that fountain, was a lack of water. I guess I was in shock, among other things, you get thirsty, and of course I hadn’t had anything to eat since breakfast. By the time the evening came, I was truly thirsty. P176_ED1

I was not well served, no. Go to the hospital, wait 14 hours, not be able to go to the toilet, not be able to have a glass of water, not be able to eat, not be able to sleep! P8_ED2_translated

Domain 2: The Needs of Family Members

This theme was defined as the needs of family members or friends to assist and comfort their relatives while accompanying them in the ED. The 2 recurring subthemes were ED care practices and policies fostering family presence and participation in care and enough space for family members to be beside the patient.

Emergency Department Care Practices and Policies Involving Family

Some participants emphasized the need for ED care practices that foster family presence and participation in care. Participants also wanted to see an ED policy giving families unlimited access to their relatives in order to be able to provide them the physical and psychological support they needed.

Good contact with the patient and the family, who was, as a matter of fact, me and my mother. Really, he [doctor] spoke very honestly. And it wasn’t like: “What is she doing here? She doesn’t belong here.” P264_ED2_daughter_translated

Well I find it very very good…It’s the hospital of our choice…it always seemed like a family hospital. P146_ED1_daughter

Space for family beside patients

Families expressed the need for space to accompany their relatives who have mobility, cognitive, or sensory problems and require regular help.

She [mother] can’t see, and she is deaf. It’s not easy. I always stayed with her. So we were sitting next to her. P248_ED4_daughter_translated

I had an exam in a room there, an ultrasound, and my daughter stayed with me. Then, I went to a room in the emergency room, and my daughter stayed with me in the room. P38_ED3_translated

Domain 3: Transitional Care Needs

Six subthemes classified under this domain were discharge information, resolution of health problems, plans for further medical care, medications, safe transport, and home care services.

Discharge Information

Many participants felt that either they did not receive the discharge information they needed, in person or in a written format, or that the purpose of the written document was not explained.

Elsewhere, they always give me a paper that says what they have, what they did, and all that I give to the residence nurse or her doctor or a copy to each person, but this time, I left with nothing. P257_ED3_friend_translated

They could give me a little more information like a date [for the operation]. Now, I am living with uncertainty, with a big question mark. P354_ED2_translated

Resolution of Health Problems

Some patients felt that they were rushed to discharge without resolving the health problems led to their ED visit. Anxious about not having resolutions, some participants sought help elsewhere or considered returning to the ED.

If they could have kept me longer…because I was given my discharge on Monday and I am still suffering from the same problems. P87_ED2_translated

My problem that I had when I left home to go to the hospital, I have the same problem. 203_ED4_translated

Plans for Further Medical Care

Some participants expressed a need for reassurance about their further medical care and other diagnostic procedures through follow-up calls from the ED or access to specialists. Although in most cases they had to wait for the service to which they were referred, which is not under control of the ED, a few felt that they did not receive the appropriate process they needed.

When you have hip pain or knee pain, maybe they think: “They will not die of it. We will treat him tomorrow.” If I had been given a specialist, access to a specialist faster, I think it is what I need. P188_ED3_translated

He [doctor] told me: “We’ll meet again, I’ll call you back,” but he did not tell me when. P35_ED3_translated

Because of anxiety over delays with receiving further care after ED visits, some participants sought help from other resources such as Info-Santé-811 support (telephone hot-line in case of a nonurgent health issue) or considered going to a private clinic.

Medication

Another important concern was about the lack of information provided before discharge about medications especially when new medications were prescribed or changed. When asked if participants received information on the reasons for prescribing new medications, how to use them or their potential side effects, they reported that they usually sought this information from the community pharmacists. As well, a few mentioned having difficulty obtaining the medication after the visit either because they were discharged at night or because the medication was unavailable at their pharmacy.

I learned them [potential side effects] when I received the antibiotics with the letter including all information. Yes, at the pharmacy. P305_ED4_translated

Because I got to the pharmacy 10 minutes before it closed, and they didn’t have any. They [ED staff] sent me home with a prescription that I couldn’t fill…It’s very stressful when you’re trying to take care of your elderly mother and you don’t have the medication necessary for them. P296_ED1_daughter

Safe Transport

Some patients underscored the need for staff to help find appropriate transport back home.

One thing I appreciated was the doctor who discharged me from the hospital. He made sure I was going home and that someone was coming to pick me up. The nurse came and told me where I could call a taxi…Everyone seemed to be preoccupied that I had a safe return home. P232_ED3_translated

Home Care Services

A few participants expressed uncertainties about whether they would receive expected home care services or what would happen if they became unable to live alone, to travel when needed, or to perform activities of daily living.

The doctor asked himself to know “If Mrs X fell down, would this be a good time to assess if she is able to remain at that residence?”, or “Should we do an evaluation to see if she needs to receive additional services or to change her residence?” The fact that the doctor was concerned about that was a plus point, in my opinion, very positive. P257_ED3_friend_translated

No, they did not clean [the wound]. I have to do it myself, and I am not able to. It is too hard. I try to call [community health center], try to see if maybe they can send me someone. I’ve not heard from them yet. P210_ED1_translated

Discussion

Emergency departments play a central role in older adults’ care transitions between the hospital and community (15). This qualitative study provided a better understanding of patients’ physical needs, while in the ED, family caregivers’ involvement in care, and experiences of patients and their families transitioning back into the community. Our findings highlight several areas that could be addressed by EDs to more appropriately respond to patients’ physical needs, enable accompanying family members to participate in care, and improve patient and family education around the time of discharge.

Meeting older patients’ physical needs in the ED, attention to physical comfort, making mobility equipment available, providing timely assistance during the ED stay, and access to food and drink were sometimes poorly addressed. There appears to be a sense of urgency to address these fundamental aspects of care. The EDs could increase patients comfort by adjusting the room temperature, providing extra blankets, or reducing lights and noise at night (3). More staffing or revision of roles may resolve time concerns in the ED environment so that the staff can assist dependent patients more actively with their activities of daily living. EDs should ensure nutritional intake and hydration by making food and beverages available on demand (3). Screening for high risk of functional decline at triage and in-depth assessments on those who screened positive (31) could help staff identify patients with special physical needs and plan their ED care. Moreover, in order to increase staff’s ability to perform best practices for preventing deconditioning, physical space should accommodate easy access to washrooms and mobilization with walkers or wheelchairs. Patients’ autonomy and independent functioning should also be facilitated with appropriate and accessible equipment such as adjustable beds and comfortable chairs (3). Volunteers may accompany older patients without accompanying family members within the fast-paced ED environment and help prevent potential decline (32). All of these measures could prevent deterioration and iatrogenic complications associated with deconditioning in the ED.

Our findings reinforced the importance of considering the needs of families accompanying patients in the ED. Enough space at the bedside allowing families to stay closer to their older relatives and become active participants in their care was reported to be fundamental. This finding parallels the literature supporting families’ role in older patients’ care. For example, as older ED patients often become anxious while waiting, having families to support them can help to alleviate this problem (19). Families are also knowledgeable about patients’ baseline level of functional capacity and their medication, which is essential for staff to know when planning further care and management at home. Families feel more satisfied when they are able to take care of their relatives, collaborate with the staff as an active participant, and provide psychological support (5). As such, ED care practices nurturing partnership with families and allocating time for ED staff to communicate with them should be established. In view of the aging population and increasing ED visits by patients with significant cognitive impairment, it has been suggested that the dyad of the older patient and their family member must be the unit of care in the ED (17).

We identified several transitional care needs as patients were returning to the community. Many participants confirmed the need for personalized and comprehensible discharge information to ensure the continuity of their care in the community. Implementing interventions targeting staff–patient communication (33) or patient-oriented discharge summaries (34) may have the potential to reduce ED return visits. Patient and families should also be given the opportunity to ask questions. Some patients complained about lack of resolution of their health problems. This could indicate inadequate patient education on what symptoms to expect or information on self-management, or possibly that they had been discharged with unrecognized problems. Filling the new ED prescriptions was often stressful, and community pharmacists were found to be a good resource to obtain instructions on new medications. It was also felt that patient referrals for further medical care were not followed up appropriately. In fact, coordination among the different health professionals is particularly important for this population who often may need different or additional services after ED visits. As such, when there are doubts, either the family doctor should be informed about recommended follow-up appointments or community services, or ED staff might do this follow-up.

Limitations and Strengths

Although we aimed for maximum variation in 4 selected EDs, participants were from the same geographical area, extrapolation to the general older population is limited. Our purpose in this qualitative study was to explore subthemes of patient experiences. For those wishing to quantify the experiences of older adults of ED care, we suggest using our previously published validated measures (21). Also, this study provides a report of interesting/relevant lines of inquiry on the 3 predetermined domains, which somewhat limits seeing all types of experiences. The difference in education level in the subsample was another limitation. This study also had some strengths. We fully described the characteristics of the subsample which was large and diverse (patients/families, ambulatory/bedside, multicultural). The internal validity was optimized: standardized telephone interview procedures by trained RAs with participants in their home setting minimized social desirability bias, the short-time lapse between the ED visit and the interviews minimized recall bias, and intercoder reliability was measured. Finally, our research designed by an interdisciplinary team fostered reflection and the adoption of multiple perspectives on the phenomenon under study.

Conclusions

Despite the existence of evidence-based geriatric ED guidelines, in our sample of 4 hospitals, patient and family experiences were often inconsistent with these recommendations. Our findings reinforced the fact that, locally, each ED could improve their care of older adults, particularly those who are unable to communicate and/or are not mobile. More emphasis is needed on preparation for the transition back home; this could be accomplished through appropriate patient education and collaboration with community-based care providers—the family doctor, community pharmacist, and home care services. Future research and quality improvement should address these areas by engaging ED and community care providers in addition to patients and family members.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Mona Magalhaes, MA, for her help with data collection and intercoder reliability of the qualitative analysis and Eric Belzile, MSc, for performing the statistical analysis.

Author Biographies

Deniz Cetin-Sahin is a research fellow at St. Mary’s Research Centre and works at Donald Berman Maimonides Center for Research in Aging while pursuing her PhD in Family Medicine and Primary Care at McGill University, Montreal, Canada.

Francine Ducharme is dean and full professor, Faculty of Nursing, University of Montreal, Canada.

Jane McCusker is a professor Emerita, Department of Epidemiology, Biostatistics and Occupational Health at McGill University, and Principal Scientist at St. Mary’s research Centre in Montreal, Canada. Her research focus is in 4 broad areas: care of vulnerable older adults in the emergency department, delirium in older adults, depression in older adults, and family caregiving.

Nathalie Veillette is an associate professor, Faculty of Medicine, Rehabilitation School, University of Montreal, and Researcher at Montreal Geriatric Institute Research Center, Canada.

Sylvie Cossette is vice-dean research and international development, Faculty of Nursing, University of Montreal, and Researcher at the Montreal Heart Institute Research Center, Canada.

T.T. Minh Vu is a clinical assistant professor in Geriatric Medicine,University of Montreal Hospital Center and Montreal Geriatric Institute, Montreal University, Canada.

Alain Vadeboncoeur is a clinical professor, University of Montreal, and emergency physician at the Montreal Heart Institute, Canada.

Paul-André Lachance is a clinical professor, University of Montreal, and emergency physician at Hôpital de la Cité-de-la-Santé, Laval, Canada.

Rick Mah is an emergency physician at St. Mary’s Hospital Center, Montreal, Canada.

Simon Berthelot is an assistant professor in the Department of Family Medicine and Emergency Medicine, Université Laval, and emergency physician at the CHU de Québec-Université Laval, Canada.

Appendix A

Key Characteristics of 4 Emergency Departments. Source: 2012/13 Quebec ED Registry

| Data Sources and Variables | ED-1 | ED-2 | ED-3 | ED-4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Source: 2012/13 Quebec Emergency Department Registry | ||||

| Number of bed | 15 | 49 | 43 | 22 |

| Level of care | Secondary | Secondary | Tertiary | Secondary |

| University affiliation | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Total number of annual visits | 38 124 | 78 814 | 74 305 | 30 310 |

| Volume of visits by aged 75+ | 19% | 17% | 6.50% | 19.50% |

| Among visits aged 75+ | ||||

| Mean length of stay (bed/ambulatory) | (22.3/4.4) | (26.2/5.9) | (15.5/3.8) | (31.7/3.4) |

| % of stretcher visit | 65% | 66% | 85% | 64% |

| % admission | 32% | 37% | 40% | 23% |

| % admission (among bed visits) | 48.1% | 55.2% | 47.1% | 35.6% |

| % admission (among ambulatory visits) | 0.3% | 1.0% | 0.1% | 0.0% |

| Source: 2013/14 survey of lead informants | ||||

| Elder friendly ED score (0-100) | ||||

| A) Screening tool and assessment | ||||

| Lead nurse | 0 | 80 | 100 | 100 |

| Lead physician | 20 | 80 | 80 | 80 |

| B) Clinical protocols and care practices for older adults | ||||

| Lead nurse | 85.7 | 42.9 | 71.4 | 57.1 |

| Lead physician | 28.6 | 42.9 | 85.7 | 57.1 |

| C) Discharge planning | ||||

| Lead nurse | 75 | 37.5 | 50 | 50 |

| Lead physician | 62.5 | 50 | 50 | 37.5 |

| Mean number of physicians in the ED | 3-4 | 5-7 | 8+ | 3-4 |

| Mean number of nurses in the ED | 7-10 | 11+ | 11+ | 11+ |

Abbreviation: ED, emergency department.

Appendix B

Open-Ended Interview Questions (Italics Show Adjustments for Families)

-

What did you like most about the care you (your [RELATIONSHIP]) received during your (her/his) visit to the emergency room?

Probes:

Is there something from your (her/his) visit that stands out for you?

Is there something about your (her/his) care that you really appreciated? It could be something about the staff (nurses, doctors, or other staff members in the emergency department [ED]), the facilities, or the way in which your (her/his) stay in the ED unfolded.

-

How could your [RELATIONSHIP’s] emergency care have been improved?

Probes:

In your opinion, how do you think your (her/his) care could have been better?

Is there anything that you saw or that happened that you really did not like?

What would you have liked to have received, or what would you have liked to have seen during your (her/his) visit to the ED?

-

Is there something else you would like to tell us about your visit to the emergency department or about the procedures involved in your departure from the emergency department?

Probe:

Is there anything else that you saw or experienced during your ED visit, from the time you arrived to the time you left, that you think we should know about, either positive or negative?

Authors’ Note: J.M., F.D., N.V., S.C., A.V., and T.T.M.V. conceived and designed the study and obtained research funding. D.C-S., J.M., and F.D. supervised the conduct of the study and data collection. P-A.L., R.M., and S.B. facilitated research ethics approval and data acquisition at the participating institutions and assisted with interpretation of data. F.D. and J.M. provided advice on data analysis. D.C-S. analyzed the qualitative data and drafted the manuscript, and all authors contributed substantially to its revision. D.C-S. takes responsibility for the paper as a whole. Portions of this work was presented at the 45th Annual Scientific and Educational Meeting of the Canadian Association on Gerontology, October 2016 and St. Mary’s Hospital Research Centre Seminar Series, October 2017, in Montreal, Quebec, Canada.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclose receipt of the following financial support for the research and/or publication of this article: This study was supported by the Quebec Research Fund—Health (#25234) and St. Mary’s Hospital Foundation (Montreal, Quebec).

References

- 1. Hustey FM, Meldon SW. The prevalence and documentation of impaired mental status in elderly emergency department patients. Ann Emerg Med. 2002;39:248–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hart B, Frank C, Hoffman J, Dickey D, Kristjansson J. Senior friendly health services. Perspectives. 2006;30:18–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Carpenter CR, Bromley M, Caterino JM, Chun A, Gerson LW, Greenspan J, et al. Optimal older adult emergency care: introducing multidisciplinary geriatric emergency department guidelines from the American College of Emergency Physicians, American Geriatrics Society, Emergency Nurses Association, and Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. Ann Emerg Med. 2014;63:e1–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Weldring T, Smith SMS. Patient-Reported outcomes (Pros) and patient-reported outcome measures (Proms). Health Serv Insights. 2013;6:61–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Nikki L, Lepisto S, Paavilainen E. Experiences of family members of elderly patients in the emergency department: a qualitative study. Int Emerg Nurs. 2012;20:193–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Shankar KN, Bhatia BK, Schuur JD. Toward patient-centered care: a systematic review of older adults’ views of quality emergency care. Ann Emerg Med. 2014;63:529–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Muntlin A, Gunningberg L, Carlsson M. Patients’ perceptions of quality of care at an emergency department and identification of areas for quality improvement. J Clin Nurs. 2006;15:1045–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Vaillancourt S, Seaton MB, Schull MJ, Cheng AHY, Beaton DE, Laupacis A, et al. Patients’ perspectives on outcomes of care after discharge from the emergency department: a qualitative study. Ann Emerg Med. 2017;70:648–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Olofsson P, Carlstrom ED, Back-Pettersson S. During and beyond the triage encounter: chronically ill elderly patients’ experiences throughout their emergency department attendances. Int Emerg Nurs. 2012;20:207–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Richardson S, Casey MM, Hider P. Following the patient journey: older persons experiences of emergency departments and discharge. Accid Emerg Nurs. 2007;15:134–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Themessl-Huber M, Hubbard G, Munro P. Frail older people’s experiences and use of health and social care services. J Nurs Manag. 2007;15:222–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lyons I, Paterson R. Experiences of older people in emergency care settings. Emerg Nurse. 2009;16:26–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Way R. Discovery interviews with older people: reflections from a practitioner. Int J Older People Nurs. 2008;3:211–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Watson WT, Marshall ES, Fosbinder D. Elderly patient’s perceptions of care in the emergency department. J Emerg Nurs. 1999;25:88–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Spilsbury K, Bridges J, Meyer J, Holman C. The little things count. Older adults’ experiences of A&E care. Emerg Nurse. 1999;7:24–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Nagurney JM, Fleischman W, Han L, Leo-Summers L, Allore HG, Gill TM. Emergency department visits without hospitalization are associated with functional decline in older persons. Ann Emerg Med. 2017;69:426–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Parke B, Hunter KF, Strain LA, Marck PB, Waugh EH, McClelland AJ. Facilitators and barriers to safe emergency department transitions for community dwelling older people with dementia and their caregivers: a social ecological study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2013;50:1206–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kelley ML, Parke B, Jokinen N, Stones M, Renaud D. Senior-friendly emergency department care: an environmental assessment. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2011;16:6–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kihlgren AL, Nilsson M, Skovdahl K, Palmblad B, Wimo A. Older patients awaiting emergency department treatment. Scand J Caring Sci. 2004;18:169–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Parke B, Hunter KF, Schulz ME, Jouanne L. Know me—a new person-centered approach for dementia-friendly emergency department care. Dementia. 2019;18:432–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. McCusker J, Cetin-Sahin D, Cossette S, Ducharme F, Vadeboncoeur A, Vu TTM, et al. How older adults experience an emergency department visit: development and validation of measures. Ann Emerg Med. 2018;71:755–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Colorafi KJ, Evans B. Qualitative descriptive methods in health science research. HERD. 2016;9:16–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. McCusker J, Vu TTM, Veillette N, Cossette S, Vadeboncoeur A, Ciampi A, et al. Elder-friendly emergency department: development and validation of a quality assessment tool. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2018;66:394–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kergoat MJ. Approche Adaptée à la Personne Âgée en Milieu Hospitalier—Cadre de Référence. Quebec, QC, Canada: La Direction des communications du ministère de la Santé et des Services sociaux du Québec; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Warburton RN, Parke B, Church W, McCusker J. Identification of seniors at risk: process evaluation of a screening and referral program for patients aged ≥75 in a community hospital emergency department. Int J Health Care Qual Assur. 2004;17:339–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Murray MJ. The Canadian Triage and Acuity Scale: a Canadian perspective on emergency department geriatric services in Quebec and correlates of these changes. Emerg Med Australasia. 2003;15:6–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gerhard K, Harald W. The qualitative heuristic approach: a methodology for discovery in psychology and the social sciences. Rediscovering the method of introspection as an example. Forum: Qualitative Social Research. 2000;1(1): Art. 13, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs0001136. [Google Scholar]

- 28. O’Reilly M, Parker N. ‘Unsatisfactory Saturation’: a critical exploration of the notion of saturated sample sizes in qualitative research. Qual Res. 2013;13:190–7. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Fleiss J, Levin B, Paik M. Statistical Methods for Rates and Proportions. 3rd ed Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Fereday J, Muir-Cochrane E. Demonstrating rigor using thematic analysis: a hybrid approach of inductive and deductive coding and theme development. Int J Qual Meth. 2006;5:80–92. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hastings SN, Heflin MT. A systematic review of interventions to improve outcomes for elders discharged from the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2005;12:978–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sanon M, Baumlin KM, Kaplan SS, Grudzen CR. Care and respect for elders in emergencies program: a preliminary report of a volunteer approach to enhance care in the emergency department. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62:365–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Taylor D, Kennedy MP, Virtue E, McDonald G. A multifaceted intervention improves patient satisfaction and perceptions of emergency department care. Int J Qual Health Care. 2006;18:238–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hahn-Goldberg S, Okrainec K, Damba C, Huynh T, Lau D, Maxwell J, et al. Implementing patient-oriented discharge summaries (PODS): a multisite pilot across early adopter hospitals. Healthc Q. 2016;19:42–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]