Abstract

Surface-enhanced Raman scattering (SERS) sensing in microfluidic devices, namely optofluidic-SERS, suffers an intrinsic trade-off between mass transport and hot spot density, both of which are required for ultra-sensitive detection. To overcome this compromise, photonic crystal-enhanced plasmonic mesocapsules are synthesized, utilizing diatom biosilica decorated with in-situ growth silver nanoparticles (Ag NPs). In our optofluidic-SERS testing, 100× higher enhancement factors and greater than 1,000× better detection limit were achieved compared with traditional colloidal Ag NPs, the improvement of which is attributed to unique properties of the mesocapsules. First, the porous diatom biosilica frustules serve as carrier capsules for high density Ag NPs that form high density plasmonic hot-spots. Second, the submicron-pores embedded in the frustule walls not only create a large surface-to-volume ratio allowing for effective analyte capture, but also enhance the local optical field through the photonic crystal effect. Last, the mesocapsules provide effective mixing with analytes as they are flowing inside the microfluidic channel. The reported mesocapsules achieved single molecule detection of Rhodamine 6G in microfluidic devices and were further utilized to detect 1 nM of benzene and chlorobenzene compounds in tap water with near real-time response, which successfully overcomes the constraint of traditional optofluidic sensing.

Keywords: Optofluidic Device, Photonic Crystals, Plasmonic Mesocapsules, Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering

Graphical Abstract

The table of contents: Hierarchical photonic crystal-enhanced plasmonic mesocapsules from diatom biosilica decorated with Ag NPs for ultra-sensitive optofluidic-SERS are presented. SERS EFs more than 100× and limit of detections greater than 1000× compared to regular colloidal Ag NPs are achieved and the mesocapsules are used to detect benzene and chlorobenzene in tap water.

1. Introduction

Recent advances in the fields of photonics and microfluidics have accelerated the development of optofluidics, in which photonic and microfluidic architectures are integrated synergistically to provide enhanced function and performance. Optofluidic devices are particularly well-suited for biological and chemical sensing. Especially, nanophotonic sensors employed in optofluidics have greatly overcome the limitations of conventional optical sensors in terms of size, sensitivity, specificity, tunability, photo-stability, and in vivo applicability [1]. Equally important, microfluidic devices enable facile delivery of sample solution to the sensing region and allow for high throughput detection. However, the limit of mass transport imposed by the laminar flow inside the microfluidic channel dictates the sensitivity and throughput of optofluidic devices [2]. In past years, various optofluidic devices have been developed using micro-ring resonators [3], metamaterials [4], surface plasmon resonance (SPR) [5], and surface-enhanced Raman scattering (SERS) [6]. As a vibrational spectroscopic technique, SERS can provide specific information about the molecular structure by the strong local optical field enhancement generated by plasmonic nanoparticles (NPs) or nanostructures [7]. Most published optofluidic-SERS results were obtained utilizing either 1) colloidal metallic NPs flowing inside microfluidic channels, or 2) SERS-active plasmonic nanostructures fabricated on the surface of the microfluidic channels to provide the necessary SERS enhancement factors (EFs). Plasmonic NPs, primarily based on silver (Ag) or gold (Au), such as colloidal metallic NPs[8], nanorods [9], nanostars [10], core-shell NPs [11], and functional NPs [12] are widely used for optofluidic-SERS sensing. This is due to the simple chemical synthesis process and the rapid mixing with the target analyte in microfluidic channel devices. In other words, colloidal NPs can largely overcome the slow diffusive process of low concentration analytes to flat surface sensors due to the uniform dispersion of colloidal NPs in solution. The exclusive advantages have spurred escalating research interests to engineer colloidal NPs. For example, Pinkhasova et al. [11a] reported Ag core-Au shell plasmonic NPs with entrapped thiocyanate label molecules immobilized in long fiber channels to allow SERS interrogation of trace levels of rhodamine 6G (R6G). Han et al. [12b] developed an optofluidic-SERS sensor using Fe3O4/Ag microspheres for detection of 4,4’-bipyridine. However, colloidal NPs usually suffer low SERS EFs because of the low plasmonic hot spot density and strength. Although using higher concentration colloidal NPs may improve the SERS EF, it will undesirably cause aggregation or deposition, both of which will degrade the sensitivity.

To increase the plasmonic hot spot density and strength, SERS-active plasmonic nanostructures fabricated on the surface of the microfluidic channels with much larger EFs have been developed. Microflowers [13], nanodisks [14], nanodimers [15], electrostatic assembling of Au NPs patterns [16], nanotubes [17], two-dimensional (2-D) periodic Cu-Ag nanostructures [18], and nanorods [19] have all been used to enhance SERS signals. For instance, Xu et al. [20] used a laser-processing technique to fabricate Ag micro-flowers at the desired position inside the microfluidic channel for in-situ monitoring of the reduction of 4-nitrophenol to 4- aminophenol. Different than optofluidic-SERS sensing relying on colloidal NPs in microfluidic channels, the detection limit using surface-deposited SERS-active plasmonic nanostructures is determined by the mass transport of target molecules to the sensor surface. As microfluidic channels support laminar flow profiles, the analyte molecules rely on very slow diffusive processes to reach the sensor surface, which can take hours or even days for sub-picomolar concentration detection [21]. Because of the slow diffusive process, very few target molecules can be captured by the surface-deposited plasmonic nanostructures, resulting in limited sensitivity. To overcome this problem, “flow-over” technique has been replaced by “flow-through” strategy to mitigate the slow mass transport experienced by most optofluidic sensors [21]. For example, Eftekhari et al. [21c] developed flow-through nanohole array to aid in mass transport. Guo et al. [22] demonstrated optofluidic Fabry-Pérot cavity label-free biosensor with integrated flow-through micro-channels. Kumar et al. [23] found that an Au/Si3N4 membrane with nanopore arrays can effectively promote flow-through via capillary flow and evaporation. Although the integration of flow-through structures with microfluidic device improves the mass transport to active sensing areas, it requires expensive nano-scale fabrication processes to create such rationally designed plasmonic nanostructures. Additionally, flow-through devices require active pumps to apply high external pressure to force the fluid through the structure, which complicates the usage of these optofluidic devices for practical applications.

As comparison to the aforementioned two plasmonic nanostructures for optofluidic-SERS devices, multi-scale hierarchical mesocapsules that use micro-scale dielectric particles with densely loaded nano-scale plasmonic NPs can offer the advantages of both colloidal NPs and surface-patterned SERS substrates. Plasmonic mesocapsules are capable of eliminating the diffusion limit due to the rapid mixing with the analyte in the microfluidic channel while still providing high density plasmonic hot spots for SERS sensing. Additionally, the porous nature of plasmonic mesocapsules offers strong adsorption to many target molecules due to Langmuir adsorption isotherm [24], which can greatly enhance the detection limit. In recent years, a few plasmonic mesocapsules have been reported for optofluidic sensing. Kohler et al. [25] utilized microfluidic synthesis of polymer capsules with a high content of Ag NPs with which adenine can easily interact with the SERS-active area. Xu et al. [26] synthesized dual functional plasmonic-magnetic mesocapsules consisting of silica microtubes with embedded solid nanomagnets and uniformly coated Ag NPs. Hollow sections generate strong SERS EFs and embedded nanomagnets serve as nanomotors to increase the mixing with the analyte from a living cell membrane. Spadaro et al. [27] developed an enhanced hybrid design of silica-Au mesocapsules for in-situ SERS monitoring using a porous silica shell. Similarly, Infusino et al. [28] and Lopez et al. [29] found that microporous silica capsules with embedded Au NPs gained strong SERS EFs in optofluidic sensing. Nevertheless, the SERS EFs of these reported mesocapsules only comes from the high density plasmonic NPs, while the porous silica shells or tubes only serve as carriers for plasmonic NPs. Improving the optofluidic-SERS sensitivity to extreme levels such as single molecule detection still remains a challenge.

In this work, we develop multi-scale, hierarchical photonic crystal-enhanced plasmonic mesocapsules made of diatom photonic biosilica decorated with in-situ synthesized Ag NPs for ultra-sensitive optofluidic-SERS sensing, as illustrated in Figure 1. Diatoms are microalgae that possess hierarchal micro- and nano-structured silica shells called frustules. Diatom frustules are comprised of highly porous, amorphous biosilica, perforated with 2-D periodic pore array that can behave as photonic crystals [30]. Unique properties of diatom biosilica include: 1) photonic crystal optical field concentration induced by the 2-D periodic pores embedded in the frustules to enhance the SERS sensitivity [30], and 2) high adsorption capacity due to Langmuir adsorption isotherm, which may effectively enhance analyte mass transport into the sensing area [24]. Our previous work theoretically and experimentally demonstrated that a diatom frustule can provide guided-mode resonance (GMR) within the visible wavelength range and can enhance the localized surface plasmonic resonances (LSPRs) of metal NPs, especially for those within the diatom’s pores [30]. We also experimentally confirmed the analyte concentration effect due to the super-hydrophilic biosilica, which induces microscopic fluid flow upon inkjet-printed liquid droplet evaporation. In this article, we demonstrated ultra-sensitive optofluidic-SERS sensing of R6G inside a microfluidic channel device with a detection limit of 10−13 M, which is essentially down to single molecule sensitivity. The multi-scale, hierarchical photonic crystal-enhanced plasmonic mesocapsules showed SERS EFs of more than 100× and enhanced detection limit of at least 1,000× compared to regular colloidal Ag NPs. Additionally, it took less than one minute for the mesocapsules to detect such low level of analytes, thus overcoming the slow mass transport of laminar flows. We also applied the mesocapsules to detect water contamination and achieved a limit of detection of 1 nM for both benzene and chlorobenzene in tap water.

Figure 1.

Schematic of optofluidic-SERS sensing using diatom photonic crystal-enhanced plasmonic mesocapsules

2. Experimental section

2.1. Materials

Silver nitrate (AgNO3), tin (II) chloride (SnCl2), ascorbic acid (AA), hydrochloric acid (HCl), R6G, benzene (Bz), and chlorobenzene (CBz) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich in the USA. Poly-dimethysiloxane (PDMS) was purchased from Dow-Sylgard in the USA. All chemicals with analytical-grade purity were used as the starting materials without further purification. Ultra-pure water (≈18 MΩ·cm) was used as a solvent in the experiments. All glassware used in the experiments was first cleaned with nitric acid.

2.2. Synthesis of photonic crystal plasmonic mesocapsules

Diatom frustules were isolated from living cell cultures of Pinnularia sp. The diatom cells were cultivated according to microbiological methods highlighted in our previous work [30a, 31]. The isolated diatom frustules in solution were used for the in-situ growth of Ag NPs, as illustrated in Figure S1 (a) in the Supporting Information (SI). The in-situ synthesis of Ag NPs on diatom frustules was conducted via the modified Tsukruk method [32]. First, 4 mL of a 50 μg/mL diatom frustule solution was added to 3 mL of 20 mM of SnCl2 and 1 mL of 20 mM of HCl for 20 min to deposit the nucleation sites of Sn2+ on the diatom frustule surface, and then washed with water and acetone using a nylon filter vials (Thomson, USA). A volume of 0.5 mL of Sn2+ deposited diatom frustule suspension was then injected into a 3 mL of 20 mM aqueous solution of AgNO3 for 20 min to grow Ag seeds on the diatom frustules followed by a second wash with a nylon filter vial. Finally, 0.5 mL of Ag-seeded diatom biosilica solution was mixed with 1.5 mL of the final growth medium (1 mL of 5 mM AgNO3 and 0.5 mL of 50 mM AA) for 20 min to grow Ag NPs on the diatom frustules followed by multiple washings with water and acetone to remove impurities. Ag NP-decorated diatom frustules were re-dispersed in MeOH or an aqueous solution and stored below 4 °C for further use. The morphology and optical properties of the synthesized Ag NPs on diatom frustules were characterized using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and UV-Vis spectrophotometry.

2.3. Method for optofluidic-SERS characterization

The design and fabrication of the microfluidic device is given in the SI. Mixture fluid (700 μL) containing various concentrations of target molecules (i.e., R6G, NB, Bz, CBz) and mesocapsules was injected through the microfluidic channel for optofluidic-SERS measurement. SERS spectra were acquired from the glass slide side by focusing the laser onto the mesocapsules using a Horiba Jobin Yvon Lab Ram HR800 Raman microscope. All of the samples were excited with a 2.0 mW, 532 nm incident laser using a 10× objective lens. The laser spot size is ~4 μm in diameter. The Raman spectra were acquired with 10-second integration time in the Raman spectral range, from 400 to 1800 cm−1. For each sensing condition, a total of 20 spectra were taken and for each figure with one representative spectrum shown. For intensity comparisons, the peak intensity for the 20 spectra were averaged and plotted with standard deviation error bars.

The EF was calculated according to the standard equation:

| (1) |

where ISERS and IBulk are the SERS and normal Raman scattering intensities, respectively. NSERS and NBulk are the numbers of molecules contributing to the inelastic Raman scattering intensity, respectively.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Characterization of photonic crystal-plasmonic mesocapsules

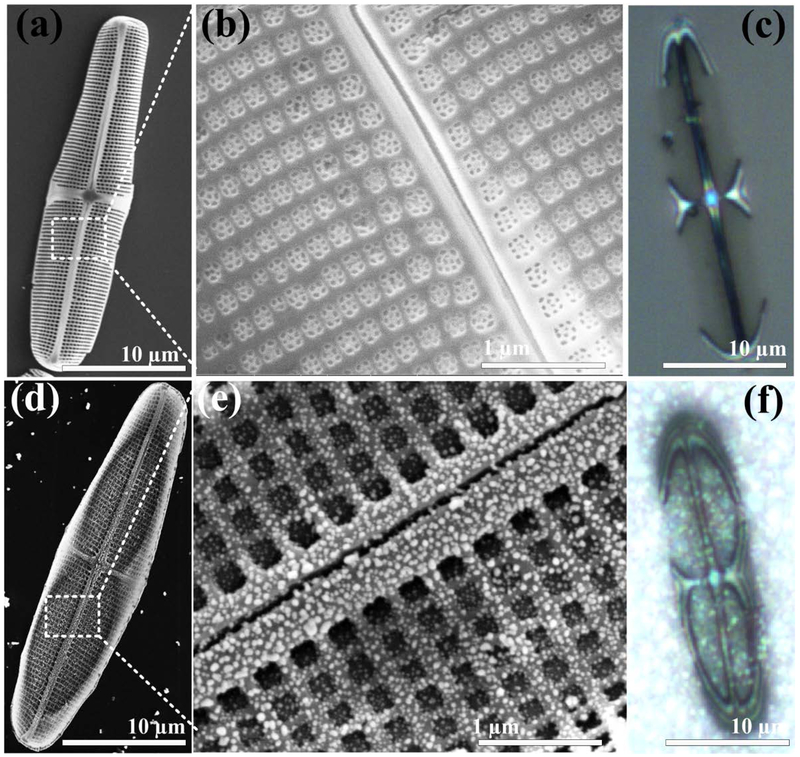

Pinnularia sp. diatoms possess elliptical frustules with hierarchical periodic pores. The SEM was employed to characterize the surface morphology of Pinnularia sp. frustules isolated from cell culture. A frustule structure with submicron features is shown in Figure 2 (a-b). The semi-elliptical dimensions for the frustule valve are ~27 and ~5 μm along the major and minor axes, respectively, with a height of ~5 μm and embedded within the frustule is a periodic 2-D array of primary nanopores with nominal diameter of −200 nm. The primary pores of the diatom frustule contain several sub-nanopores with diameters of 20-50 nm.

Figure 2.

SEM top-view images of diatom frustules (a-b) and in-situ synthesized Ag NPs on diatom biosilica surface (d-e). Optical images of diatom frustules and plasmonic mesocapsules in microfluidic channels (c and f).

The morphological features of the diatom frustules provide large reaction sites inside or nearby the pore for in-situ growth of Ag NPs. Additionally, the diatom frustule surface is rich in silanol groups [30a, 31], which increase the quantity of nucleation site and the reaction rate. The Ag NPs were immobilized with a high density on the diatom frustule surface as shown in Figure S1 (a). After each reaction step of in-situ growth of Ag NPs on the diatom frustule, it was rinsed with ethanol and aqueous solution and then filtered by nylon filter vials to effectively remove the impurities and ions that are not anchored to the diatom surface. The concentrated diatom biosilica was added into an aqueous mixture of SnCl2 and HCl for 15 min, resulting in securely anchored and uniformly distributed nucleation sites of Sn2+ ions deposited on the diatom frustule surface. This was achieved due to the strong interactions between Sn2+ and the hydroxyl groups of the diatom frustule. Such interactions lower the mobility of Sn2+ and increase the formation of nucleation sites and prevent the growth of large tin particles. The diatom frustules were then added into an aqueous AgNO3 solution for 10 min, which rapidly reduced the Ag seeds on the pores. Most of the Ag-seed formation on the diatom frustule surface from the salt solutions was successfully achieved following the first reduction reaction, which also allows the small Ag seeds in the submicron pores.

| (2) |

The formation of larger high-density Ag NPs on the diatom frustule surface greatly depends on the Ag seeds through a heterogeneous nucleation mechanism with various factors, such as the free energy of different phases, concentration of the growth solution, and surface energy of the particles [31a, 32]. The density and particle size of Ag NPs on the diatom frustule surface can be controlled by a homogenous growth mechanism, which provides a limited growth step with respect to the diffusion of growth particles in the solution and the concentration of the growth medium. The larger uniform Ag NPs were grown on the Ag seeds deposited on the diatom frustule surface by submerging the frustules in a final growth medium containing a mixture of AgNO3 and ascorbic acid for 10 min. The FE-SEM top-view images of the hybrid photonic crystal-plasmonic mesocapsules are shown in Figure 2(d-e). The Ag NPs on the diatom pore surface are nearly spherical in shape with a diameter of 45 ± 5 nm. The higher density Ag NPs on the diatom frustule surfaces were formed by controlling the final growth time and optimizing the growth medium concentration. The growth samples in Figure 2 show that Ag NPs are densely packed with narrow gaps in the nearby pore areas of the diatom frustule surface. This proximity generates strong local field effect and improves the SERS signals. The optical images of a single diatom frustule and a photonic crystal-plasmonic mesocapsule in solution are shown in Figure 2(c) and (f).

Due to the small index contrast, diatom biosilica possess only very small or even no true photonic bandgaps [33]. The periodic structure of diatom frustule, however, does induce GMRs, which can be coupled with the LSPRs of metallic nanoparticles to enhance the SERS sensitivity, which have been both thoeretically and experimentally investigated in our previous publications [34]. Figure S2 (a) shows the extinction spectra of diatom frustules in solution, colloidal Ag NPs and photonic crystal enhanced-plasmonic mesocapsules. Diatom frustules show weak but relatively broad extinction at 500-600 nm wavelength range due to the nonideal GMR effect, which comes from the imperfect periodic structure of diatom frutules. The SPR peak of colloidal Ag NPs appears at 390 nm, suggesting that Ag NPs were evenly dispersed in the aqueous solution without aggregation and with uniform diameters of 40-50 nm. A strong SPR extinction peak of the photonic crystal enhanced-plasmonic mesocapsules appears at 425 nm with a shoulder at 579 nm. The red shift of the Ag NP SPR is attributed to the increase of the refractive index of the dielectric media due to the presence of diatom biosilica, while the shoulder at 579 nm marks the end of the hybrid Ag SPR-diatom photonic crystal resonances [35].

3.2. SERS characterization of photonic crystal-plasmonic mesocapsules in fluid

The optofluidic properties of photonic crystal-plasmonic mesocapsules were first characterized by UV-visible and SERS measurement. A 700-μL mesocapsule solution with a concentration of 10 μg/mL was injected into a cuvette and the extinction spectra were measured with the interrogating light source focused towards the top of the cuvette. The extinction spectra of the mesocapsules in the solution as a function of time (0 to 7 min) are shown in Figure S2 (b) in SI. Initially, the peak position of the mesocapsule absorption at 425 nm was strong thus confirming the suspension of the mesocapsules in solution. Under static environment, the extinction peak gradually decreased due to the deposition of mesocapsules. Regular colloidal Ag NPs were used as a reference, where the results are similar to that of the mesocapsules.

An optofluidic reservoir with 3mm diameter was fabricated using PDMS material and is shown in Figure S3 (a). For SERS examination, R6G at a concentration of 10−6 M was mixed with the solution containing mesocapsules and was injected into the reservoir and covered by a glass slide. In Figure S3 (b) in SI, the SERS spectra from the mesocapsule solution were measured at different time using a 532 nm Raman laser. The SERS characteristic peak of R6G appears at 1362 cm−1, which is assigned to the C-C stretching modes [36]. The SERS characteristic peak intensity gradually decreased as time progressed, which is consistent with the results from the extinction spectra as shown in Figure S3 (c) in SI. Therefore, all optofluidic-SERS measurements in Section 3.3 were taken within one minute after injecting the mesocapsules into the optofluidic reservoir or microfluidic channels.

In Figure 3(a), the SERS spectra of R6G were measured at concentrations of 10−5 to 10−14 M mixed with mesocapsules and regular colloidal Ag NPs in the optofluidic reservoir. The strong characteristic SERS peak at 1362 cm−1 was used to obtain the SERS EFs. The mesocapsules exhibit absolute SERS EFs of 108~1011× when the R6G is below 1nM, which are more than 100× greater when compared to the regular colloidal Ag NPs as shown in Figure 3(b). A maximum average optofluidic-SERS EF of 4.49×1011 was achieved at a 10−14 M R6G concentration from the mesocapsules, which achieved a detection limit of 1,000× better than that of colloidal Ag NPs. At the concentration of 0.01 pM, our calculation in the SI shows that there are only 3.8 × 10−4 molecules within the detection volume if we assume the R6G molecules are evenly distributed in the solution. However, we can still reliably detect the R6G signals at 0.01pM, which should be attributed to the analyte concentration effect at the porous diatom frustule surface due to Langmuir adsorption isotherm [24]. Nevertheless, we are still confident to assume single-molecule detection at this extremely low concentration level, which highlights the ability of our mesocapsules for ultra-sensitive optofluidic-SERS detection.

Figure 3.

SERS spectra of 10−5-10−14 M R6G molecules mixed with photonic crystal enhanced-plasmonic mesocapsules in the optofluidic reservoir interrogated by Raman laser wavelength 532-nm (a). Log-scale EFs were compared between photonic crystal enhanced-plasmonic mesocapsules and colloidal Ag NP samples (b).

3.3. Real-time optofluidic-SERS sensing

We performed optofluidic-SERS sensing in a PDMS microfluidic channel device, the fabrication of which is detailed in the SI. Figure 4 (a) shows the bright and dark-field optical images of the microfluidic device with photonic crystal enhanced-plasmonic mesocapsules. First, 500 μL of mesocapsule solution and 200 μL of various concentrations of R6G (10−5 to 10−13 M) analyte solution was mixed and injected into the microfluidic device and the SERS signals were detected under stationary condition. The SI video file shows the mixture solution of the mesocapsules injected into the microfluidic channel. With the mesocapsule-analyte solution in the sensing area of the microfluidic channel, measurements are taken with a laser integration time of 10 seconds over a sensing area of 4×4 μm2. Figure 4 (b) shows the SERS spectra of different concentrations of (10−5 to 10−13 M) R6G mixed with mesocapsules in the microfluidic channel. The limit of detection was determined to be 0.1 pM and the correlation coefficient was 0.95, which is shown in Figure S3 (d) in the SI. Note that R6G concentrations near 0.1 pM are clearly single-molecule SERS detection since there are only 3.8 × 10−3 R6G molecules within the area of the laser spot by uniform distribution assumption.

Figure 4.

Dark and bright-field images of mesocapsules in microfluidic channel (a). SERS spectra of 10−5-10−13 M R6G molecules mixed with photonic crystal-plasmonic mesocapsules solution in optofluidic channel (b). Log EF of photonic crystal-plasmonic mesocapsules and colloidal Ag NPs samples were compared (c). Measured real-time SERS signal as a function of the R6G concentrations mixed with photonic crystal-plasmonic mesocapsules in optofluidic channel, over time (d). The line color indicates target molecule concentration; (red: 1 mM, blue: 1nM, Green: 1 pM).

In Figure 4(c), the average EFs of the mesocapsules at different concentrations using the 1362 cm−1 Raman peak were compared to those of regular colloidal Ag NPs. The average EF values of mesocapsules reached as high as 2.2×1010 at 10−13 M R6G. The mesocapsules exhibited SERS EFs of more than 100× greater than those achieved using regular colloidal Ag NPs, thus showing similar enhancement effects in a microfluidic channel as in the previous stationary fluidic reservoir. Compared with other reported optofluidic-SERS sensing using plasmonic mesocapsules, our photonic crystal-enhanced plasmonic mesocapsules exhibit much greater SERS EFs, which is summarized in Table S1 in the SI. This unprecedented optofluidic-SERS EFs can be attributed to the multi-functional nature of diatom photonic crystals. First, the diatom frustules serve as the matrix for high density Ag NPs, which form plasmonic resonance inside the gaps. Second, the photonic crystal effect can further enhance the plasmonic resonance effects [30], although the enhancement can possibly be reduced in microfluidic devices due to the smaller index contrast between biosilica and fluid. Third, the hydrophilic surface of diatom pores can absorb target molecules in the solution due to Langmuir adsorption isotherm [24], allowing physical concentration of the analyte and facilitates better mass transport to the sensing area [37]. Quantitative analysis of these three different effects is beyond the scope of this manuscript and will be investigated in our future research.

The response of the optofluidic-SERS system to different concentrations of analyte was also tested. Figure 4(d) shows the real-time SERS sensing of mesocapsules mixed with various concentrations of R6G. The mixed solution started with an analyte concentration of 1 mM, which was injected for 1 minute, after which three SERS spectra were acquired at 20 second intervals. Solution containing 1 nM R6G was then injected and measured for the same time intervals followed by a solution with 1 pM analyte concentration. Measurements were then taken by, again, injecting 1 nM and then 1 mM R6G solutions at the same 1 minute injection intervals and 20 second measurement intervals. As the R6G concentration was reduced, the intensity of the SERS signal immediately decreased, indicating that the mesocapsules mixed with the target analyte in the microfluidic channel permitted in-situ, continuous SERS detection during the injection. Such near-real-time SERS response proves that such multi-scale, hierarchical photonic crystal-enhanced plasmonic mesocapsules can successfully break the constraint of sensitivity-response time of traditional optofluidic sensing.

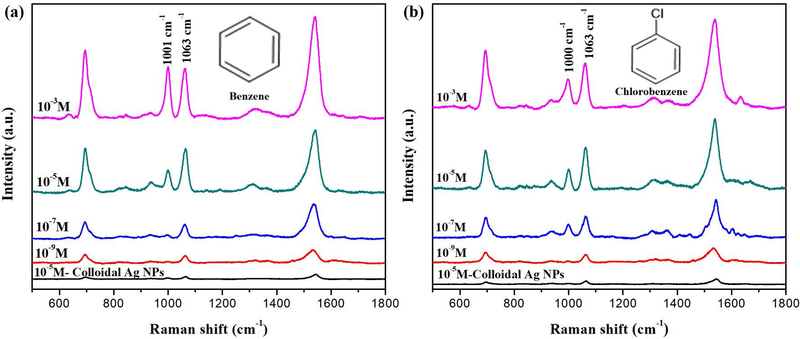

3.4. Optofluidic-SERS sensing of water contamination molecules

Optofluidic-SERS sensing using the photonic crystal enhanced-plasmonic mesocapsules was applied for water quality monitoring. Benzene and chlorobenzene are volatile organic compounds (VOCs) and are colorless aromatic liquids [38], which can pollute groundwater through atmospheric deposition, petroleum products, and chemical plant effluents. Benzene and chlorobenzene are toxic and have deleterious effects to human health and environment. Exposure to organic compounds leads to short-term health issues, such as anemia and temporary nervous system disorders, and long-term health issues including cancer and chromosome aberrations. A U.S. federal survey estimated that 1.3% of all groundwater systems contain benzene at concentrations greater than 0.5 μg/liter [39]. Consequently, various analytical techniques have been applied over the past decade for the detection of benzene and chlorobenzene in ground water, including mass spectrometry, liquid/gas chromatography, and enzyme-linked immune sorbent assay methods [40]. Although those analytical methods provide high sensitivity, they require sample preparation and are time-consuming and expensive. Therefore these methods are not suitable for on-site sensing.

In our experiment, various concentrations of benzene and chlorobenzene were mixed with tap water and further mixed with the mesocapsules. Figure 5(a) and (b) show the measured SERS spectra of benzene and chlorobenzene using the photonic crystal enhanced plasmonic mesocapsules. The strong SERS feature peaks at 1000 cm−1 and 1063 cm−1 is attributed to the ring breathing mode and in-plane deformation mode [41], respectively. These two peaks are still distinguishable at the 1 nM detection limit, corresponding to 0.05 μg/liter, which is 10× lower than the safety level. Compared with optofluidic-SERS sensing using colloidal Ag NPs with detection limit of only 10−5M as shown in Fig. 5, this detection limit is four orders of magnitude better.

Figure 5.

SERS spectra of 10−3-10−9 M benzene and chlorobenzene in water solutions mixed with photonic crystal-plasmonic mesocapsules solution, or colloidal Ag NPs (black), in optofluidic channel examined by Raman laser wavelength 532-nm(a-b). The inset shows chemical structures of benzene and chlorobenzene.

4. Conclusion

In summary, we have synthesized multi-scale, hierarchical photonic crystal-enhanced plasmonic mesocapsules made of diatom photonic biosilica decorated with in-situ growth Ag NPs to achieve ultra-sensitive optofluidic-SERS sensing with more than 100× higher EFs and at least 1,000× improvement in detection limit compared with traditional colloidal Ag NPs. The holistic improvement in optofluidic-SERS sensing comes from multiple unique features including high density Ag NPs assembled on the porous diatom biosilica frustules, photonic crystal enhancement to the plasmonic hot spots, effective analyte capture due to the porous submicron-pores embedded in the frustule walls, and effective mixing with analytes as the mesocapsules are flowing inside the microfluidic channel. The reported biological photonic crystal-enhanced plasmonic mesocapsules achieved single molecule detection of Rhodamine 6G in microfluidic devices and were further utilized to detect 1 nM of benzene and chlorobenzene compounds in tap water with near real-time response, which successfully overcomes the constraint of traditional optofluidic sensing. We expect that optofluidic-SERS sensors using diatom photonic crystal-enhanced plasmonic mesocapsules can potentially play pivotal roles in a broad spectrum of sensing applications including water quality monitoring, environmental protection, food sensing, forensic analysis, and drug abuse detection.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

This work was financially supported by the National Institutes of Health under Grant No. 1R21DA0437131, the National Science Foundation under Grant No. 1701329, and the United States Department of Agriculture under Grant No. 2017-67021-26606.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

Supporting Information is available from the Wiley Online Library or from the author.

Reference

- [1] a).Hoa XD, Kirk AG, Tabrizian M, Biosensors and Bioelectronics 2007, 23, 151; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Anker JN, Hall WP, Lyandres O, Shah NC, Zhao J, Van Duyne RP, Nat Mater 2008, 7, 442; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Stewart ME, Anderton CR, Thompson LB, Maria J, Gray SK, Rogers JA, Nuzzo RG, Chemical Reviews 2008, 108, 494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Brolo AG, Nat Photon 2012, 6, 709; [Google Scholar]; e) Inhee C, Yeonho C, Selected Topics in Quantum Electronics, IEEE Journal of 2012, 18, 1110; [Google Scholar]; f) Raschke G, Kowarik S, Franzl T, Sönnichsen C, Klar TA, Feldmann J, Nichtl A, Kürzinger K, Nano Letters 2003, 3, 935. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Sheehan PE, Whitman LJ, Nano Letters 2005, 5, 803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Mancuso M, Goddard JM, Erickson D, Optics express 2011, 20, 245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Bang S, Kim J, Yoon G, Tanaka T, Rho J, Micromachines 2018, 9, 560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Li D, Lu B, Zhu R, Yu H, Xu K, Biomicrofluidics 2016, 10, 011913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6] a).Lim C, Hong J, Chung BG, deMello AJ, Choo J, Analyst 2010, 135, 837; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Yazdi SH, White IM, Analytical Chemistry 2012, 84, 7992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Luo S-C, Sivashanmugan K, Liao J-D, Yao C-K, Peng H-C, Biosensors and Bioelectronics 2014, 61, 232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8] a).Hoonejani MR, Pallaoro A, Braun GB, Moskovits M, Meinhart CD, Nanoscale 2015, 7, 16834; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Pallaoro A, Hoonejani MR, Braun GB, Meinhart CD, Moskovits M, ACS Nano 2015, 9, 4328; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Zhang Z, Gernert U, Gerhardt RF, Höhn E-M, Belder D, Kneipp J, ACS Catalysis 2018, 8, 2443. [Google Scholar]

- [9].Kim D, Campos AR, Datt A, Gao Z, Rycenga M, Burrows ND, Greeneltch NG, Mirkin CA, Murphy CJ, Van Duyne RP, Haynes CL, Analyst 2014, 139, 3227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Nguyen AH, Lee J, Il Choi H, Seok Kwak H, Jun Sim S, Biosens Bioelectron 2015, 70, 358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11] a).Pinkhasova P, Chen H, Kanka J, Mergo P, Du H, Applied Physics Letters 2015, 106; [Google Scholar]; b) Yamaguchi A, Fukuoka T, Takahashi R, Hara R, Utsumi Y, Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical 2016, 230, 94. [Google Scholar]

- [12] a).Wang G, Li K, Purcell FJ, Zhao D, Zhang W, He Z, Tan S, Tang Z, Wang H, Reichmanis E, ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2016, 8, 24974; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Han B, Choi N, Kim KH, Lim DW, Choo J, The Journal of Physical Chemistry C 2011, 115, 6290. [Google Scholar]

- [13].Xu BB, Zhang R, Liu XQ, Wang H, Zhang YL, Jiang HB, Wang L, Ma ZC, Ku JF, Xiao FS, Sun HB, Chem Commun (Camb) 2012, 48, 1680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Li M, Zhao F, Zeng J, Qi J, Lu J, Shih W-C, J. Biomed. Opt 2014, 19, 111611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Perozziello G, Candeloro P, De Grazia A, Esposito F, Allione M, Coluccio ML, Tallerico R, Valpapuram I, Tirinato L, Das G, Giugni A, Torre B, Veltri P, Kruhne U, Della Valle G, Di Fabrizio E, Opt Express 2016, 24, A180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Wu Y, Jiang Y, Zheng X, Jia S, Zhu Z, Ren B, Ma H, R Soc Open Sci 2018, 5, 172034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Lamberti A, Virga A, Chiadò A, Chiodoni A, Bejtka K, Rivolo P, Giorgis F, Journal of Materials Chemistry C 2015, 3, 6868. [Google Scholar]

- [18].Bai S, Serien D, Hu A, Sugioka K, Advanced Functional Materials 2018, 28. [Google Scholar]

- [19].Xie Y, Yang S, Mao Z, Li P, Zhao C, Cohick Z, Huang P-H, Huang TJ, ACS Nano 2014, 8, 12175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Xu BB, Ma ZC, Wang H, Liu XQ, Zhang YL, Zhang XL, Zhang R, Jiang HB, Sun HB, Electrophoresis 2011, 32, 3378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21] a).Guo Y, Li H, Reddy K, Shelar HS, Nittoor VR, Fan X, Applied Physics Letters 2011, 98, 041104; [Google Scholar]; b) Huang M, Yanik AA, Chang T-Y, Altug H, Optics Express 2009, 17, 24224; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Eftekhari F, Escobedo C, Ferreira J, Duan X, Girotto EM, Brolo AG, Gordon R, Sinton D, Analytical Chemistry 2009, 81, 4308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Guo Y, Li H, Reddy K, Shelar HS, Nittoor VR, Fan X, Applied Physics Letters 2011, 98. [Google Scholar]

- [23].Kumar S, Cherukulappurath S, Johnson TW, Oh SH, Chem Mater 2014, 26, 6523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24] a).Yin Y, Langmuir 1991, 7, 216; [Google Scholar]; b) Sigal GB, Mrksich M, Whitesides GM, Langmuir 1997, 13, 2749; [Google Scholar]; c) Armatas GS, Salmas CE, Louloudi M, Androutsopoulos GP, Pomonis PJ, Langmuir 2003, 19, 3128. [Google Scholar]

- [25].Köhler JM, März A, Popp J, Knauer A, Kraus I, Faerber J, Serra C, Analytical Chemistry 2013, 85, 313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Xu X, Li H, Hasan D, Ruoff RS, Wang AX, Fan DL, Advanced Functional Materials 2013, 23, 4332. [Google Scholar]

- [27].Spadaro D, Iatí MA, Pérez-Piñeiro J, Väzquez-Väzquez C, Correa-Duarte MA, Donato MG, Gucciardi PG, Saija R, Strangi G, Maragò OM, The Journal of Physical Chemistry C 2017, 121, 691. [Google Scholar]

- [28].Infusino M, De Luca A, Veltri A, Väzquez-Väzquez C, Correa-Duarte MA, Dhama R, Strangi G, ACS Photonics 2014, 1, 371. [Google Scholar]

- [29].Mariño-Lopez A, Sousa-Castillo A, Blanco-Formoso M, Furini LN, Rodríguez-Lorenzo L, Pazos-Perez N, Guerrini L, Pérez-Lorenzo M, Correa-Duarte MA, Alvarez-Puebla RA, ChemNanoMat 0. [Google Scholar]

- [30] a).Kong X, Squire K, Li E, LeDuff P, Rorrer GL, Tang S, Chen B, McKay CP, Navarro-Gonzalez R, Wang AX, IEEE Trans Nanobioscience 2016, 15, 828; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Kong X, Xi Y, LeDuff P, Li E, Liu Y, Cheng LJ, Rorrer GL, Tan H, Wang AX, Nanoscale 2016, 8, 17285; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Wang AX, Kong X, Materials (Basel) 2015, 8, 3024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31] a).Kong X, Xi Y, Le Duff P, Chong X, Li E, Ren F, Rorrer GL, Wang AX, Biosens Bioelectron 2017, 88, 63; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Jeffryes C, Gutu T, Jiao J, Rorrer GL, Materials Science and Engineering: C 2008, 28, 107. [Google Scholar]

- [32].Chang S, Combs ZA, Gupta MK, Davis R, Tsukruk VV, ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 2010, 2, 3333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].De Stefano L, Maddalena P, Moretti L, Rea I, Rendina I, De Tommasi E, Mocella V, De Stefano M, Superlattices and Microstructures 2009, 46, 84. [Google Scholar]

- [34] a).Ren F, Campbell J, Rorrer GL, Wang AX, IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Quantum Electronics 2014, 20, 127; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Kong X, Squire K, Li E, LeDuff P, Rorrer GL, Tang S, Chen B, McKay CP, Navarro-Gonzalez R, Wang AX, IEEE Transactions on NanoBioscience 2016, 15, 828; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Kong X, Xi Y, LeDuff P, Li E, Liu Y, Cheng L-J, Rorrer GL, Tan H, Wang AX, Nanoscale 2016, 8, 17285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35] a).Mogensen KB, Kneipp K, The Journal of Physical Chemistry C 2014, 118, 28075; [Google Scholar]; b) Liu X, Li D, Sun X, Li Z, Song H, Jiang H, Chen Y, Scientific Reports 2015, 5, 12555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Sivashanmugan K, Liao J-D, You J-W, Wu C-L, Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical 2013, 181, 361. [Google Scholar]

- [37] a).Chen L, He X, Liu H, Qian L, Kim SH, The Journal of Physical Chemistry C 2018, 122, 11385; [Google Scholar]; b) Cyran JD, Donovan MA, Vollmer D, Siro Brigiano F, Pezzotti S, Galimberti DR, Gaigeot MP, Bonn M, Backus EHG, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2019, DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1819000116; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Schrader AM, Monroe JI, Sheil R, Dobbs HA, Keller TJ, Li Y, Jain S, Shell MS, Israelachvili JN, Han S, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2018, 115, 2890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Weisel CP, Chemico-biological interactions 2010, 184, 58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39] a).Health criteria and other supporting information, World Health Organization 1996, 2; [Google Scholar]; b) US environmental protection agency 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40] a).Huang G, Gao L, Duncan J, Harper JD, Sanders NL, Ouyang Z, Cooks RG, Journal of the American Society for Mass Spectrometry 2010, 21, 132; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Maiolini E, Knopp D, Niessner R, Eremin S, Bolelli L, Ferri EN, Girotti S, Analytical sciences : the international journal of the Japan Society for Analytical Chemistry 2010, 26, 773; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Marrubini G, Dugheri S, Pacenti M, Coccini T, Arcangeli G, Cupelli V, Manzo L, Biomarkers 2005, 10, 238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41] a).Ito M, Shigeoka T, Spectrochimica Acta 1966, 22, 1029; [Google Scholar]; b) Williams JH, Becucci M, Chemical Physics 1993, 177, 191; [Google Scholar]; c) Krasser W, Ervens H, Fadini A, Renouprez AJ, Journal of Raman Spectroscopy 1980, 9, 80. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.