Abstract

We consider the situation where there is a known regression model that can be used to predict an outcome, Y, from a set of predictor variables X. A new variable B is expected to enhance the prediction of Y. A dataset of size n containing Y, X and B is available, and the challenge is to build an improved model for Y|X,B that uses both the available individual level data and some summary information obtained from the known model for Y|X. We propose a synthetic data approach, which consists of creating m additional synthetic data observations, and then analyzing the combined dataset of size n+m to estimate the parameters of the Y|X, B model. This combined dataset of size n+m now has missing values of B form of the observations, and is analyzed using methods that can handle missing data (e.g. multiple imputation). We present simulation studies and illustrate the method using data from the Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial. Though the synthetic data method is applicable to a general regression context, to provide some justification, we show in two special cases that the asymptotic variance of the parameter estimates in the Y|X, B model are identical to those from an alternative constrained maximum likelihood estimation approach. This correspondence in special cases and the method’s broad applicability makes it appealing for use across diverse scenarios.

Keywords: Synthetic data, constrained maximum likelihood, data integration, prediction models

1. INTRODUCTION

In clinical biomedicine, many well-known models are used to predict a measure of disease from patient characteristics. Examples include but are not limited to the breast cancer risk calculator (Gail et al., 1989), and the colorectal cancer risk assessment tool (Freedman et al., 2009). These models are usually constructed from large datasets using principled statistical methods to predict a measure of risk or disease state, treating the patient characteristics as predictors. The patient characteristics, denoted as X, can range from traditional epidemiologic, behavioral variables to well-known imaging, genetic and other molecular biomarkers. The predicted outcome variable Y, and the predictors X, are often assumed to be connected through a regression model of the form Y|X. The individual level original data that were used to construct this model are usually not available to the public but what are accessible are certain forms of summary-level information. This information can be available in the form of coefficient estimates for the fitted model, individual prediction probabilities or multiple prediction probabilities from competing models for the same outcome. The equations underlying the existing model may or may not be known.

While these existing models are often based on traditional epidemiologic and behavioral risk factors and well-established biomarkers, wider availability of high throughput data and novel assay technologies are generating new candidate biomarkers, say B, for possible inclusion in existing risk prediction models. Due to the potential improvement of prediction accuracy of the current model, it is ideal to incorporate B into the well-established model Y|X, and construct an expanded prediction model of interest Y|X,B. However, it is very likely that B and X are assessed only on participants in a study of moderate size and cannot be retrospectively measured on the much larger population used for Y|X model. It is natural to consider using the information from the well-established model to increase the accuracy of the expanded model. This represents a general statistical challenge to build a good model for Y|X, B that uses both the known external information from the Y|X model and the individual level data from a small sample dataset of Y, X and B.

There exist proposals in the literature to incorporate external information into regression estimation. Imbens & Lancaster (1994) investigate how aggregate data (e.g. the population average of the response) could be used to improve ML estimates in a regression model. More recently, Grill et al. (2015) proposed a simple method of incorporating new markers into an existing calculator via Bayes Theorem. Chatterjee et al. (2016) developed a constrained semi-parametric maximum likelihood (CSPML) method for incorporating external coefficients to calibrate the current regression model. The performance of various approaches was assessed in a simulation study by Grill et al. (2017). Cheng et. al (2018, 2019) proposed constrained ML and Bayes methods to incorporate information obtained from external sources into regression estimation. In general, the constrained ML approaches require a specific form for the external information, e.g. estimated coefficients from a correctly specified mean model and assumptions regarding the transportability of the distribution of Y, X,B across the internal and external sample. The constrained maximum likelihood (CML) approach proposed in Cheng et al. (2018) also requires the specification of a model for B|X and relies on some parametric assumptions. Although the CSPML approach does not require the Y|X model to be correctly specified or a model for B|X, it does require the transportability of the X distribution, unless it is known in the external sample. Estes, Mukherjee & Taylor (2018) and Cheng et al. (2018) have found that the violations of this assumption and the small sample size in the internal data will cause sensitive and unstable estimation.

In this paper, we propose a synthetic data framework as a more flexible solution to this genre of problems, motivated by methods developed in the survey methodology literature (Reiter, 2002; Raghunathan, Reiter & Rubin, 2003; Reiter & Kinney, 2012). In this approach synthetic data for Y and X are generated from the Y|X model and added to the observed data, then from this combined dataset a model for Y|X, B is built. Our method relaxes the requirement on the information that is available from the external model such that the only requirement is the ability to generate predictions of Y given X.

The following is the structure of the remainder of this article: in Section 2, we introduce the notation, assumptions and implementation of the proposed synthetic data method. In Section 3, under various simulation scenarios, we evaluate the performance of the synthetic data method. We demonstrate the proposed method through an application to the Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial (PCPT) data in Section 4. We provide some theoretical justification and insight for the synthetic data method in Section 5. In two special cases we show that with a very large number of synthetic observations, our approach gives identical asymptotic variances for the parameters of the Y|X, B model as the constrained maximum likelihood (CML) estimation approach that exists in the literature. Because the CML is a maximum likelihood estimator, it is optimal if the models are correctly specified. Since the synthetic data method has the same asymptotic variance, it can also be considered optimal. Concluding remarks are presented in Section 6.

2. METHOD

2.1. General Description of the Problem

Let Y denote the outcome of interest, which can be either continuous or binary. X is a set of p standard variables and let B denote a new biomarker. There are two populations, an external population for which we do not have individual level data and an internal population for which we do have a dataset of size n with subject level data. We will assume that the distributions of Y|X, B are the same in the two populations, and likewise for the Y|X distribution. Our target of interest is the mean structure of Y|X, B:

| (1) |

where g is the known link function. We assume that a small dataset of size n with variables Y, X and a new covariate B is available to us for building the model of interest.

We assume a large, well-characterized previous study from the external population describes the provided information on the calculated distribution of Y|X. This information can come in various forms, including partial or full knowledge of the distribution of the Y|X model.

2.2. Synthetic Data Method

We propose an algorithmic approach that can produce synthetic data on (Y, X, B), by using the combination of the available information from the established model and the observations from the current dataset. The synthetic data would incorporate the external information as well as enlarge the sample size, and thus it helps improve the inference about coefficients γ in model 1, compared to just analyzing the small dataset based on the observed data.

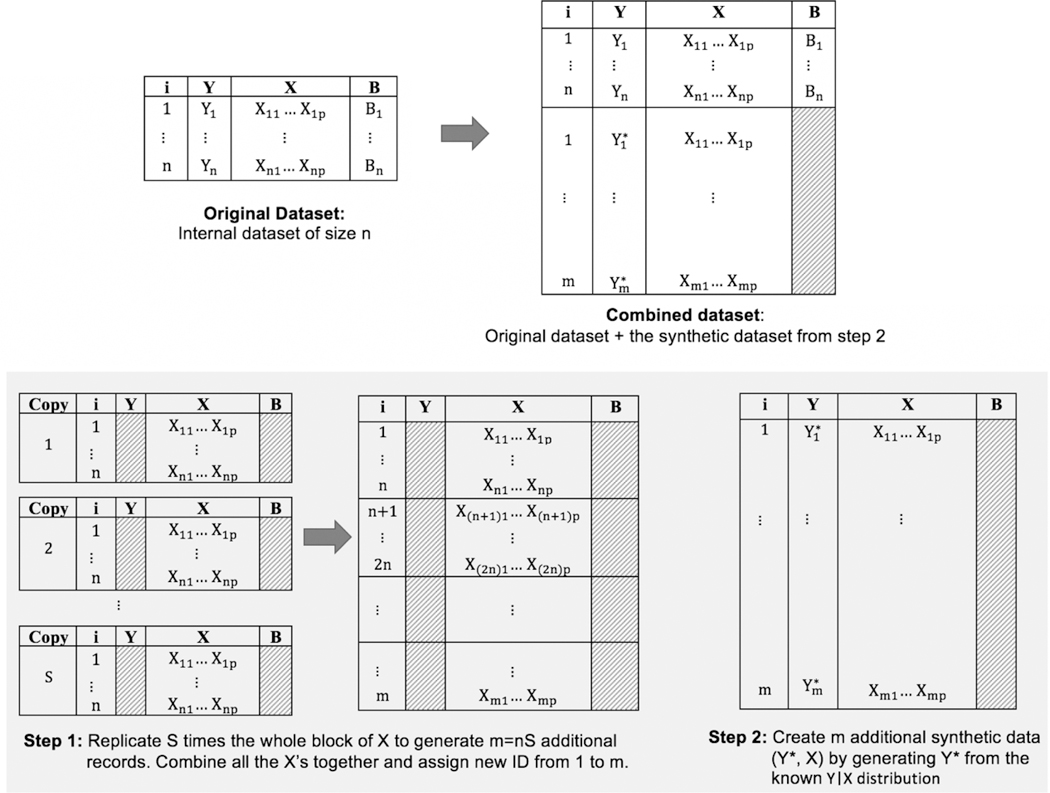

The synthetic data approach consists of creating m additional synthetic data observations, and then analyzing the combined dataset of size n+m to estimate the parameters of model (1). The synthetic data are created in two steps as shown in Figure 1. In step 1, we replicate X a large number (say S) times in blocks of n rows to create m = nS additional records. In step 2, we generate pseudo data called Y* from the known Y|X distribution for these new m records. Finally, we combine the synthetic observations with the original dataset, and we note that the combined data will now have missing values of B for m observations. The combined data is then analyzed to give an estimate of γ.

Figure 1:

Two steps to create the synthetic data

There may be different ways in which the combined data can be analyzed. In Section 5 we present two special cases for which a closed-form maximum likelihood estimate γ exists for the combined dataset of size n+m. In other cases, like the simulation study settings in Section 3,no closed-form solution for the maximum likelihood estimate of γ exists, and our proposed approach to deal with missing data is to use multiple imputation to impute the m missing values of B. Multiple imputation is a general procedure for analyzing datasets with missing values. It consists if defining a procedure to fill in the missing values, then applying that procedure many times to create many separate complete datasets. Each completed dataset is then analyzed and the results of these separate analyses are combined to give final estimates. In this particular case the multiple imputation approach requires us to specify a parametric model (B|X, Y), from which we draw 50 values of B to give 50 completed datasets. Then we fit model 1 for each complete data (Y, X, B) of size n+m. We then average the estimates of γ from the 50 complete datasets, and compute the total variance using Rubin’s rules (Rubin, 1987). We then proceed with inference.

Multiple imputation has the additional advantage of being able to handle multiple biomarkers in B, some of which may be discrete and some continuous. It also allows for flexible structure for the conditional mean model for each biomarker in B given all other variables in the dataset, such as the possibility to incorporate non-linearity and interactions. For implementing multiple imputation, we use the R package MICE (Van Buuren & Groothuis-Oudshoorn, 2011). We use the function mice with imputation algorithm logreg (the Bayesian logistic regression model with flat prior) for the imputation of a binary B and the imputation algorithm norm (the Bayesian linear regression model) for the imputation of a continuous B. In the situation in which there are multiple B’s, say B1 and B2, imputations are done sequentially. That is, first draw B1 from the B1 |X, Y, B2 distribution, then draw B2 from the B2|X, Y, B1 distribution, and iterate between B1 and B2.

3. SIMULATION STUDY

To assess the performance of the proposed synthetic data method for both estimation and prediction, we conduct simulation studies under four different scenarios. Each scenario has a different true distribution for Y|X, B and for B|X for the internal data. For both the outcome and the predictors we consider both continuous and binary variables to illustrate the computational implementation in a range of situations. We also consider the situation of multiple B’s to evaluate the applicability of the synthetic method in the multi-dimensional cases. In some cases a misspecified imputation model is used within the synthetic data approach, thus allowing us to evaluate the robustness of the method. Only in special cases (see Section 5) can we provide a theoretical justification for the synthetic data approach, thus the simulations are intended to provide numerical properties of the synthetic data approach in situations where the relevant theoretical properties are not yet available.

In real situations, we expect a moderate number of X variables, and their joint distribution could be quite complex with skew distributions and correlations between different X’s. To achieve this we adopted a procedure of generating X’s as described in Xu, Daniels & Winterstein (2016). We generate 9 correlated X’s in each of the four simulation scenarios as described below:

where N+ and N− represent half normal distributions, and either one or the other is selected with the shown probability. We then generate B from the B|X distribution, and finally generate Y from the Y|X, B distribution. For scenario 1 (where Y is continuous, as described below) the form of the external model for Y|X is readily available. For cases (scenarios 2, 3, and 4 where Y is binary, as described below) where the closed-form of model Y|X is not available, we numerically derive the external model Y|X. Specifically, we generate an independent dataset of (Y, X, B) of size 10000 and fit a linear or logistic regression model g(E(Y|X)) depending on the type of Y. The estimated coefficients of this model serve as the external information we obtained from the established model Y|X.

For each simulation scenario, we first simulate 500 datasets of size n. Then we create the synthetic data following the steps introduced in Section 2, and combine them with the original data to get 500 datasets of size n+m with m missing B values. For each simulated dataset, we create 50 complete datasets by imputing the missing B values given Y and X. In all four scenarios, we use linear additive models for imputing from the B|X, Y distribution, without including any interaction terms. We compare the results of the synthetic data method to the direct MLE, which uses the complete dataset of size n, in terms of estimation accuracy and prediction ability. We report the average estimated coefficients, standard deviation and 95% coverage rate for To measure the predictive performance, we generate a new dataset of size 1500 for each scenario, and evaluate the prediction in this new dataset. In the new dataset, let denote the average of the generated Y values. For the continuous Y, we use the mean squared error (MSE) defined as For binary Y, we use AUC and scaled Brier score (defined as as measures of predictive performance.

The four simulation scenarios and results are described as follows:

-

Scenario 1: Y and B are Gaussian distributed. The true model of and Bi is simulated as The corresponding Y|X model is The current data sample size n = 200, replication number S = 10, and thus the synthetic data sample size m = nS = 2000.

The results in Table 1 for scenario 1, show that compared to the direct MLE, the synthetic data method leads to obvious reduction in standard deviation of γX’s and good coverage rates of confidence intervals. In addition, it is able to reduce the MSE closer to the true value by 50%.

-

Scenario 2: Y is binary and B is Gaussian distributed. The true model of Y|X, B is which gives is simulated as The current data sample size n = 400, S = 10, and m = nS = 4000.

In Table 2, where Y is binary and B follows Gaussian distribution, including B into the regression model can reduce the scaled Brier score by 15 %, and improve the AUC by 9 %.

-

Scenario 3: Y and B are both binary. The true model of Y|X, B is and Bi is simulated as The Pr(Y = 1) and Pr(B = 1) are around 0.5 and 0.55, respectively, and n = 400, S = 8, and m = nS = 3200.

The simulation results in Table 3 for scenario 3, in which Y and B are both binary, show that including B in the regression model can reduce the scaled Brier score by 10.8 %, and increase the AUC by 5%.

-

Scenario 4: Y is binary and two mixed types of B are included, one binary and another Gaussian. The true model of Y|X, B1, B2 is from P(Y=1) is approximately 0.53. The binary B1i; is simulated as which gives The Gaussian B2i is simulated as where n = 400, S = 8, and m = nS = 3200.

The results in Table 4 show that the synthetic data method does improve the scaled Brier score and AUC compared to the MLE and these almost attain the best possible values, and that the coverage rates of the confidence intervals for the γ’s are good.

Table 1:

Simulation results for scenario 1 with Gaussian Y, one Gaussian B and nine correlated X’s: for each method, we report mean (Monte Carlo standard deviation) [95 % coverage rate] and MSE across 500 simulated datasets.

| Not including B | True value | Direct MLE | Synthetic Data Method | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| γ0 | 0 | 0 | −0.04 (0.14) [97%] | 0.00 (0.18) [96%] |

| γX1 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.50 (0.13) [94%] | 0.51 (0.08) [95%] |

| γX2 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.48 (0.13) [94%] | 0.50 (0.07) [95%] |

| γX3 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.49 (0.12) [95%] | 0.50 (0.07) [95%] |

| γX4 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.50 (0.11) [98%] | 0.50 (0.07) [95%] |

| γX5 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.50 (0.13) [93%] | 0.50 (0.08) [93%] |

| γX6 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.50 (0.12) [94%] | 0.50 (0.07) [95%] |

| γX7 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.50 (0.12) [94%] | 0.50 (0.07) [95%] |

| γX8 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.50 (0.11) [97%] | 0.50 (0.07) [95%] |

| γX9 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.50 (0.13) [94%] | 0.51 (0.07) [95%] |

| γB | − | 0.5 | 1.00 (0.13) [95%] | 1.00 (0.11) [95%] |

| MSE | 0.464 | 0.334 | 0.355 | 0.345 |

Table 2:

Results for simulation scenario 2 with binary Y, one Gaussian B and nine correlated X’s: for each method, we report mean (Monte Carlo standard deviation) [95 % coverage rate], average scaled Brier score and AUC across 500 simulated datasets

| Not including B | True value | Direct MLE | Synthetic Data Method | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| γ0 | 0.849 | 1 | 1.00 (0.17) [94%] | 0.96 (0.08) [92%] |

| γX1 | 0.435 | 2 | 2.01 (0.29) [96%] | 1.92 (0.24) [94%] |

| γX2 | 0.432 | 2 | 2.00 (0.28) [96%] | 1.90 (0.23) [94%] |

| γX3 | 0.437 | 2 | 2.01 (0.28) [95%] | 1.90 (0.23) [95%] |

| γX4 | 0.433 | 2 | 2.01 (0.30) [96%] | 1.91 (0.24) [95%] |

| γX5 | 0.422 | 2 | 2.02 (0.28) [95%] | 1.90 (0.24) [93%] |

| γX6 | 0.421 | 2 | 2.01 (0.28) [97%] | 1.89 (0.23) [93%] |

| γX7 | 0.431 | 2 | 2.01 (0.29) [96%] | 1.91 (0.23) [94%] |

| γX8 | 0.415 | 2 | 2.00 (0.27) [97%] | 1.89 (0.23) [94%] |

| γX9 | 0.445 | 2 | 2.01 (0.29) [96%] | 1.92 (0.23) [95%] |

| γB | − | −3 | −3.02 (0.45) [97%] | −2.85 (0.43) [95%] |

| Scaled Brier score | 0.801 | 0.680 | 0.702 | 0.686 |

| AUC | 0.767 | 0.837 | 0.828 | 0.835 |

Table 3:

Results for simulation scenario 3 with binary Y, one binary B and nine correlated X’s: for each method, we report mean (Monte Carlo standard deviation) [95 % coverage rate], average scaled Brier score and AUC across 500 simulated datasets

| Not including B | True value | Direct MLE | Synthetic Data Method | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| γ0 | −0.328 | −1 | −1.00 (0.21) [94%] | −1.00 (0.15) [96%] |

| γX1 | 0.305 | 0.2 | 0.20 (0.13) [94%] | 0.20 (0.05) [96%] |

| γX2 | 0.318 | 0.2 | 0.21 (0.13) [95%] | 0.21 (0.05) [94%] |

| γX3 | 0.296 | 0.2 | 0.20 (0.13) [95%] | 0.21 (0.05) [95%] |

| γX4 | 0.296 | 0.2 | 0.19 (0.13) [93%] | 0.20 (0.05) [95%] |

| γX5 | −0.066 | −0.2 | −0.21 (0.13) [94%] | −0.19 (0.05) [96%] |

| γX6 | −0.405 | −0.2 | −0.20 (0.13) [96%] | −0.20 (0.06) [96%] |

| γX7 | −0.420 | −0.2 | −0.19 (0.13) [96%] | −0.21 (0.06) [95%] |

| γX8 | −0.698 | −0.5 | −0.50 (0.15) [93%] | −0.51 (0.06) [96%] |

| γX9 | −0.713 | −0.5 | −0.51 (0.14) [95%] | −0.52 (0.06) [94%] |

| γB | − | 1.5 | 1.50 (0.28) [96%] | 1.49 (0.28) [95%] |

| Scaled Brier score | 0.750 | 0.666 | 0.687 | 0.669 |

| AUC | 0.789 | 0.833 | 0.823 | 0.831 |

Table 4:

Results for simulation scenario 4 with binary Y, binary B1 and continuous B2 and nine correlated X’s: for each method, we report mean (Monte Carlo standard deviation) [95 % coverage rate], average scaled Brier score and AUC across 500 simulated datasets

| Not including B | True value | Direct MLE | Synthetic Data Method | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| γ0 | 0.250 | −0.2 | −0.197 (0.21) [96%] | −0.13 (0.15) [93%] |

| γX1 | 0.441 | −0.2 | −0.19 (0.19) [96%] | −0.14 (0.13) [94%] |

| γX2 | 0.779 | 0.2 | 0.21 (0.21) [94%] | 0.23 (0.13) [94%] |

| γX3 | −0.132 | 0.2 | 0.19 (0.17) [95%] | 0.17 (0.10) [94%] |

| γX4 | −0.218 | 0.1 | 0.09 (0.17) [95%] | 0.08 (0.10) [95%] |

| γX5 | 1.047 | 0.1 | 0.10 (0.26) [96%] | 0.15 (0.21) [95%] |

| γX6 | 0.705 | −0.1 | −0.10 (0.28) [94%] | −0.06 (0.21) [94%] |

| γX7 | 0.529 | −0.3 | −0.29 (0.27) [94%] | −0.25 (0.21) [93%] |

| γX8 | −0.750 | 0.3 | 0.29 (0.25) [97%] | 0.23 (0.21) [95%] |

| γX9 | −0.757 | 0.3 | 0.30 (0.25) [96%] | 0.22 (0.21) [94%] |

| γB1 | − | 1 | 0.996 (0.31) [96%] | 0.88 (0.30) [93%] |

| γB2 | − | 2 | 1.99 (0.45) [95%] | 1.83 (0.43) [93%] |

| Scaled Brier score | 0.637 | 0.575 | 0.598 | 0.582 |

| AUC | 0.849 | 0.876 | 0.868 | 0.873 |

Overall, the simulation studies show that: (1) the synthetic data method can improve the efficiency of estimating γx’s and reduce the MSE of the predictions and increase the AUC for binary Y; (2) In scenario 1 where the B|X, Y model used for imputation is correctly specified, there is no bias in the estimates of γB and the γx’s; (3) In scenarios 2, 3 and 4 where the B|X, Y model used in the imputation is mis-specified, despite the improved predictive performance there is some bias in the estimates of γB and the γx’s. In future work, we will investigate if even further improvements in performance can be achieved using alternative or more flexible or more nonparametric approaches for imputing B.

4. PROSTATE CANCER PREVENTION TRIAL DATA EXAMPLE

To assess the performance of the synthetic data method in a real example, we apply it to the Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial calculator. The high-grade prostate cancer calculator (PCPThg) (Thompson et al., 2016), predicts the probability of high-grade prostate cancer derived from a logistic regression based on standard clinical variables – PSA level, age, DRE findings, prior biopsy result and ethnicity. The equation for the model is:

| (2) |

where pi is the probability of observing high grade prostate cancer for subject i. A detailed description of the calculator and the external and internal and a validation dataset are given in Tomlins et al. (2015) and Cheng et al. (2018). We consider incorporating two biomarkers that have been shown to be predictive of prostate cancer into model 2. One is prostate cancer antigen 3 (PCA3), a continuous variable, and the other is the indicator variable of TMPRSS2:ERG (T2:ERG) gene fusions. We consider 3 different expanded models, one with the addition of PCA3 only, one with the addition of T2:ERG only and one with the addition of both PCA3 and T2:ERG. To compare the coefficient estimation across methods, we show the estimated coefficients and standard errors in Table 5 from 679 observations in the internal dataset. To compare prediction power, we calculate the scaled Brier Score and the AUC based on the validation dataset with 1218 observations.

Table 5:

Expanded PCPThg model: for each method, point estimate (standard error) from the internal dataset, and the scaled Brier score and the AUC from the validation dataset. The sample size of the internal dataset is 679. The sample size of the validation dataset is 1218. Replicate number S=10 giving m=6790 in the synthetic data method.

| Model | PSA | Age | DRE findings |

Prior biopsy history |

Race | PCA3 | T2:ERG | Scaled Brier Score |

AUC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Original PCPThg | 1.29 | 0.031 | 1.00 | −0.36 | 0.96 | - | - | 0.933 | 0.707 |

| Estimated PCPThg | 1.06(0.18) | 0.033 (0.012) | 1.15 (0.26) | −1.44(0.27) | 0.44 (0.29) | - | - | 0.975 | 0.716 |

| Expanded model with PCA3 score | |||||||||

| Direct regression* | 0.97 (0.19) | 0.009 (0.013) | 1.06 (0.27) | −1.27 (0.27) | 0.05 (0.31) | 0.56 (0.08) | − | 0.953 | 0.767 |

| Synthetic data method | 1.30 (0.08) | 0.012(0.006) | 0.91 (0.13) | −0.56 (0.12) | 0.50 (0.14) | 0.57 (0.08) | − | 0.878 | 0.765 |

| CSPML | 1.22(0.08) | 0.007 (0.005) | 0.86 (0.10) | −0.20 (0.08) | 0.58 (0.11) | 0.56 (0.097) | − | 0.888 | 0.759 |

| Expanded model with binary T2:ERG | |||||||||

| Direct regression* | 0.98 (0.18) | 0.032 (0.012) | 1.02 (0.26) | −1.41 (0.27) | 0.57 (0.29) | − | 0.76 (0.20) | 0.930 | 0.744 |

| Synthetic data method | 1.21 (0.07) | 0.030 (0.005) | 0.96 (0.10) | −0.59 (0.09) | 0.99(0.11) | − | 0.76 (0.22) | 0.897 | 0.741 |

| CSPML | 1.14(0.07) | 0.032 (0.004) | 1.06 (0.14) | −0.52(0.11) | 0.80 (0.17) | − | 0.72 (0.20) | 0.931 | 0.742 |

| Expanded model with PCA3 score and binary T2:ERG | |||||||||

| Direct regression* | 0.94 (0.19) | 0.010(0.010) | 1.00 (0.28) | −1.27 (0.28) | 0.15 (0.31) | 0.52 (0.08) | 0.47 (0.21) | 0.928 | 0.776 |

| Synthetic data method | 1.23(0.09) | 0.008 (0.007) | 0.83 (0.13) | −0.53 (0.11) | 0.63 (0.15) | 0.55 (0.10) | 0.45 (0.20) | 0.867 | 0.773 |

| CSPML | 1.20(0.08) | 0.008 (0.005) | 0.78 (0.11) | −0.21 (0.09) | 0.67 (0.12) | 0.52 (0.10) | 0.48 (0.27) | 0.879 | 0.769 |

Firth corrected MLE is used

For both of the expanded PCPThg models incorporating PCA3 score or binary T2:ERG, if we compare the standard errors across different methods, it is easily seen that the synthetic data method can reduce the standard errors of regression coefficients compared to direct regression by at least 50%.

The expanded PCPThg model incorporating both PCA3 score and binary T2:ERG fitted to the training dataset again shows that the method can reduce the standard errors of regression coefficients compared to direct regression. The results in Table 5 show no improvement in AUC from using the synthetic data approach compared to direct MLE, but noticeable improvement in the Brier score.

We also include in Table 5 the estimates from applying the constrained semiparametric maximum likelihood method (CSPML). It is a published method that can be applied in this case. We see it gives similar predictive performance as the synthetic data method, but the estimated coefficients differ.

5. ALGEBRAIC JUSTIFICATION IN TWO SPECIAL CASES

5.1. Estimation and Variance of γ

To establish that the synthetic data approach is asymptotically as efficient as constrained ML approaches, we consider two special cases where closed-form results of MLE for the combined dataset of size n+m in the synthetic data approach are available, so multiple imputation does not need to be used. For these cases, we compare the synthetic data approach to the basic constrained ML method (CML, Cheng et al., 2018) and the constrained semi-parametric ML method (CSPML, Chatterjee et al., 2016). These two maximum likelihood approaches are optimal based on their assumptions. The standard ML approach based on just the observed data without incorporating external information is also provided for reference comparison. For each approach, we derive the explicit formulas for the asymptotic variance of estimated coefficients, namely, in model (1).

The rationale for studying these two examples in depth is to establish some theoretical underpinning for the synthetic data approach. Given its broad applicability to other more general situations with a mixed set of continuous and categorical multivariable predictors in X and B, a justification in simpler cases that can be studied analytically makes the approach more plausible in other situations where studying the analytical properties is not immediate.

As needed we will be considering three different likelihoods, one based on the distribution Y|X, B, one based on the distribution (Y, B)|X and one based on the joint distribution of Y, X and B. When writing distributions, we will include the parameters when necessary, e.g. f (Y|X, B, γ), but parameters will be excluded when not necessary.

For this study we either know the full form of the distribution of Y|X, the mean of which may be characterized by a linear combination of X’s, as given in equation (3), with known β’s and a known link function g1:

| (3) |

or we just know the mean structure but not the full distribution of Y|X.

As mentioned earlier, our interest lies in building the mean structure of the Y|X, B distribution as given in model 1. For some approaches, we will also need to consider the relationship between X and B for which we specify a model, the mean of which is given by

| (4) |

We note that for all of these models there may be additional parameters necessary to define the full distributions (e.g. the variance σβ for Gaussian Y). But for ease of notation we will not include these additional parameters unless it is necessary, thus we denote the distributions as f(Y|X, β), f(Y|X, B, γ) and f(B|X, θ).

As a reference comparison, we will also present results for standard ML estimation on a complete dataset of size n. In this approach, we estimate the parameters of model (1) using the internal dataset of Y, X, and B without taking the external summary-level information into account. We obtain the estimates by maximizing the likelihood over γ. Then the asymptotic covariance matrix of is obtained from the inverse of the Fisher information matrix.

Approach 1:The synthetic data method. In special cases in which a direct solution is possible, the likelihood for a dataset of size n+m is and can also be written as This likelihood is then maximized over γ and θ to obtain the ML estimates and the asymptotic variance is obtained from the inverse of the Fisher information.

- Approach 2: Constrained ML on a complete dataset of size n. For this approach we posit a model f(B|X, θ) then maximize the likelihood which can be written as

subject to a constraint on the parameters that is derived from the external information. The equality gives a relationship between the unknown parameters γ, θ and the known parameter β. Assuming θ can be written as a function of γ and β, i.e. as θ(γ, β), then since is known the optimization problem becomes an unconstrained optimization problem, specifically maximization of

with respect to γ using the known value β* of β. We consider two variations of the CML method: Approach 2.1 where only the coefficients β are known, and Approach 2.2 where both β and σβ are known. -

Approach 3: Constrained semi-parametric ML method applied to a dataset of size n. For this method, the estimates are obtained by maximizing the likelihood over γ and the empirical distribution of (X, B), subject to a constraint. In this approach the distribution of (X, B) is treated nonparametrically, and the constraint is derived from the integrated score equation of model (3). In this case the constraint is . The constrained optimization problem is implemented via Lagrange multipliers and gives both an estimate of γ and the non-parametric MLE of the distribution of (X, B). The asymptotic variance of for this approach is given by where

withIntuitively, the asymptotic variance of this constrained ML estimator is the inverse of information matrix I of f (Y|X, B, γ) plus the additional information due to knowing β from the external study CL−1CT.

5.2. Description of two special cases

In the following two special cases, the goal is to derive the asymptotic efficiency of through a closed-form expression for and then compare the efficiency gain among all three approaches through the Asymptotic Relative Efficiency (ARE) of ’s, compared to from the standard MLE. This will show how much efficiency we can gain by incorporating the external information from the Y|X model and what determines that gain. We provide all the algebraic details of the derivations in the Appendix.

5.2.1. Special Case 1: Y and B are Gaussian distributed

In this section, we assume that Y and B are continuous and have a Gaussian distribution, and assume the identity link for g1 and g2 in models (3) and (4).

Without loss of generality, we consider a simplified situation where p = 1. We also assume the marginal means of Yi, Xi and Bi are all equal to zero, thus we use a no intercept model. Let denote the variance of X. Then

| (5) |

| (6) |

| (7) |

Depending on the information available from the external model Y|X, we consider two possible situations which correspond to two different constraints. The first situation is when the estimated coefficient β = β* is known from model 5. This gives the constraint The second situation is when both of the estimated coefficient β = β* and the variance are known.

For the standard MLE of the complete dataset of size n, it is easy to show that the asymptotic variance of are equal to respectively. The detailed algebraic derivation for each of the three approaches can be found in Appendix A1–A3. The comparison results for all three approaches are shown in Table 6.

TABLE 6:

Summary of 3 approaches when Y and B are Gaussian

| Approach | Method for including external information |

Available form of the external information |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard MLE (ref) | None | NA | 1 | 1 |

| 1: Synthetic data method | m additional synthetic data observations | Ability to draw Y values from Y|X distribution, regardless of the form | 1 − D | |

| 2: Constrained MLE (Cheng et al., 2018) | Constraint | 2.1: The estimated coefficient β is known. | 1 − A | 1 |

| 2.2: Both of the estimated coefficient β and the standard deviation σβ are known. | 1 − D | |||

| 3: CSPML (Chatterjee et al., 2016) | Constraint | Known expectation of Y| X | 1 − A | 1 |

{Synthetic Data, CML, CSPML}

5.2.2. Special case 2: Y, X, B are all binary

Assume we are interested in a saturated model:

| (8) |

describing the joint effect of X, B on Y, when Y, X, B are all binary variables. The external information from model 3 can be expressed as:

| (9) |

The association between B and X is defined through the model:

We denote P(X = a, Y = b) as the probability of (X = a, Y = b) combination and P(B = 0, X = a, Y = b) as the probability of (B = 0, X = a, Y = b) combination, where The detailed derivation for each of the three approaches can be found in Appendix B1–B4. The comparison results, showing the ARE’s, for all three approaches are given in Table 7.

TABLE 7:

Summary of 3 approaches when Y, X and B are binary

| Approach | Method for including external information |

Available form of the external information |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||

| Standard MLE (ref) | None | NA | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 1: Synthetic data method | m additional synthetic data observations | Ability to draw Y values from Y|X distribution, regardless of the form | 1 − F† | 1 − G‡ | 1 |

| 2: Constrained MLE (Cheng et al., 2018) | Constraint | Known estimated coefficient β | 1 − F | 1 − G | 1 |

| 3: CSPML (Chatterjee et al., 2016) | Constraint | Known expectation of Y|X | 1 − F | 1 − G | 1 |

5.3. SUMMARY

Based on the detailed derivation in Appendix, in Tables 6 and 7, we summarize the methods and the assumed forms of the summary-level external information from the Y|X model for each approach. The result of ARE of variance compared to the variance from the standard MLE is also given for each of the special cases.

Let the asymptotic relative efficiency under approach M relative to the standard MLE (without external information) be denoted by where M. ∈ {Synthetic Data, CML(2.1), CML(2.2), CSPML} for Gaussian Y, and M ∈ {Synthetic Data, CML, CSPML} for binary Y.

Result 1. Special case 1: (Y, B) continuous and normally distributed

where Table 6 summarizes the results. In summary, the synthetic data method has the same asymptotic variance as the CML (approach 2.2), and both are more efficient than the CSPML and the CML (approach 2.1). For the CSPML and the CML (approach 2.1) are more efficient than the standard MLE. For the CSPML and the CML (approach 2.1) have the same efficiency as the standard MLE.

Result 2.Special case 2: (Y, X, B) all binary

where Table 7 summarizes the results. In conclusion, the synthetic data method, CML and CSPML all converge to the same asymptotic variance. For they are more efficient than the standard MLE. For they have the same efficiency as the standard MLE.

5.4. Justification from another perspective

In the two special cases, we show that using the synthetic data approach with very large m gives identical asymptotic variance for the parameters of model (1) as the constrained ML approach. Below we provide a different intuitive justification for the synthetic data approach, for a more general situation, if certain conditions apply. Assume that Y and B are scalar random variables and that X is a vector of covariates. We will assume parametric models for all the conditional distributions, and these can be written as f (Y, B|X,ϕ), f (Y|X, B,γ), f (Y|X, β), f (B|X, θ) and f (B|X, Y, κ). Assume that f(Y|X, B, γ) is the model of interest, and that f(Y|X, β) is the form of the model that was fit to the external data, and that the estimate of β from the external data approximates the true value of β. We assume that all these models represent the true distributions and are compatible with each other in the sense that f(Y, B|X, ϕ) = f (Y|X, B, γ) × f (B|X, θ) = f (B|X, Y, κ) × f (Y|X, β). We assume there is a 1-to-1 mapping between ϕ and (γ, θ) and between ϕ and (κ, β), and that κ and β are distinct and that γ and θ are distinct. With these conditions, we can write f (Y, B|X, ϕ) as f (Y, B|X, κ, β).

With this set-up, the constrained ML estimate is obtained by maximizing the likelihood over ϕ, subject to the known β. This can be rewritten as maximizing the likelihood over κ, subject to the known β. Then from the combination of the estimate of κ and the known β we can obtain the estimate of γ.

The synthetic data method consists of maximizing the likelihood

which is equivalent to maximizing

over κ and β. When optimizing over β for fixed κ, the second term dominate the optimization procedure when m is very large. Thus the estimate of β will essentially reproduce the known value from the external data (since this was the value used to generate the synthetic data). Thus the synthetic data method will reduce to the maximization of the remaining part of the likelihood fixed, which is exactly the constrained ML method.

The requirement that all the conditional distributions are compatible with each other will not usually be true, but maybe a reasonable approximation if flexible enough models are being used. The conditions do hold for the normal and the tri-binary examples in Section 5.2.1 and 5.2.2. Another case where they hold is when Y and B follow a bivariate normal distribution given X, i.e. Then the constrained ML is to maximize the likelihood

6. DISCUSSION

In this paper, we have introduced the synthetic data method for incorporating summary-level information from well-established external models into the regression model estimation based on internal data. We demonstrate in some special cases that with a large number of synthetic data observations, the synthetic data approach is asymptotically as efficient as the constrained ML approach. This provides some justification for what at first sight might seem to be an adhoc approach. In a simulation study, we demonstrate the ability of the method to improve the predictive ability of the model

A key advantage of the synthetic data method is that it naturally incorporates the prior knowledge into the internal data by creating large “fake” data that is compatible with the Y|X established model. By creating pseudo-data from Y|X instead of constrained optimization, the synthetic data method not only simplified the task from solving complex constrained optimization, but also provides a potentially more flexible and general framework to handle this problem. The only requirement for the synthetic data approach is the ability to generate Y values given X from the information of the external models, without the need to know the exact form of model. It is broadly applicable for general data types for Y, X and B, and when B is more than one new biomarker. It can be extended to the situation where more than one external model is available, i.e. Y|X1, Y|X2,...,Y|Xk. In this setting, a combination of external studies that measured overlapping but necessarily identical covariates can provide joint information to develop a model for Y|X model, where X is the union of X1, X2,...,Xk.

The CSPML approach is also broadly applicable, and can handle multiple B’s, and it has some optimality properties. But it does require knowledge of the form of the Y|X model and requires that the distribution of the X’s are identical in the external and the internal populations, which seems unlikely to be satisfied in practice.

When analyzing the synthetic dataset, the value of B can be considered as missing, which converts the problem of incorporating external information into a problem of analyzing data with missing values. If multiple imputation procedures are to be used to impute the value of B, then further research would be needed to suggest efficient and robust ways in which this should be implemented. There is the potential to improve even further on the method by using different ways of imputing B, beyond the approach we illustrated in the simulation study.

Another interesting issue that will need to be investigated is the size of m. The theoretical result in this paper suggests that m should be very large, but this is under the assumption that the Y|X and Y|X, B models are compatible with each other. In practice, they are unlikely to be exactly compatible, which would suggest limiting the size of m. A pragmatic suggestion is to make m equal to the size of the external data, if that is known. By doing this the amount of information in the synthetic data about the relationship between Y and X is similar to the amount of information in the external data about the relationship between Y and X.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was partially supported by the National Science Foundation and National Institutes of Health.

APPENDIX

Derivation of asymptotic variances for the special case 1.

Appendix A1. Approach 1: Synthetic data method

If the synthetic data approach is applied, and under the assumption that the true value of β and σβ are used to generate the synthetic data, then the combined data will have the same distribution as a dataset of size n+m in which m values of B have been removed. For this particular data structure, it is possible to obtain formulas for the asymptotic variance of the maximum likelihood estimates of γ. In particular, Gourieroux and Monfort (1981) give the exact expression of the ML estimators and the corresponding asymptotic covariance. The likelihood for the combined data is which can be rewritten as Based on this they introduce a set of transformed parameters, and re-parameterized the distributions (5)–(7). They then identify the 1-to-1 relationship among the original parameters and the new set of parameters.

We obtain the estimators of the original parameters by the re-parameterization method, and then apply the delta method to get the asymptotic variance of According to Gourieroux and Monfort (1981), we introduce a set of transformed parameters a, b, c, d, and e, and re-parameterized the distributions (5)–(7) as We then identify the 1-to-1 relationship among the original parameters and the new set of parameters:

| (1) |

The ML estimators and their asymptotic variances are easy to obtain from the linear model where i = 1,...,n+m. Similarly, the ML estimators and their asymptotic variances are easy to obtain from the linear model where i= 1,...,n. The estimators of the original parameters are obtained through the relationship derived from equations (1), where

and the asymptotic variance of can be derived using the delta method:

From this we find the relative efficiency gain of by adding m synthetic data observations compared to the original dataset of size n is

where When m gets very large such that . This demonstrates some gain in efficiency for both

Appendix A2. Approach 2: Constrained MLE

Depending on the information available from the external model Y|X, there are two possible situations which correspond to two different constraints:

-

Approach 2.1: Only the estimated coefficient β is known from model (5)

For model (5)–(7), it is easy to see that the constraint describing the relationship between the unknown variable θ, the known variable β and the target variable γ is given by The log-likelihood is given by(2) The goal is to maximize the log-likelihood (2) over γ, σγ and σθ subject to the constraint θ = θ*, where By replacing θ with θ*, taking the derivative over γ, and taking inverse of the matrix, we obtain the asymptotic variance of equals to The corresponding ARE’s can be found in table 6, where we notice that there is some gain in efficiency for γX but no gain in efficiency for γB We can see that the largest gain in efficiency is when γB, θ and σX are small.

-

Approach 2.2: Both of the estimated coefficient β and the standard deviation σβ are known from model (5)

In this situation, knowing the true σβ gives us more information which is incorporated through an additional constraint. In addition to the constraint used in approach 2.1, we add another constraint Then the log-likelihood (2) is maximized with respect to Note that different from approach 2.1, and γ are not independent anymore. Thus, we need to consider in the information matrix, and take the inverse of a 3 × 3 matrix to get the correct asymptotic variance.

LetBy taking the inverse of I, we can get the asymptotic variance ofThus, we find that the ARE of from the constrained MLE compared to the standard MLE is identical to the synthetic data method (approach 1). This demonstrates the asymptotic equivalence of the synthetic data approach with large m, to the constrained ML approach that uses knowledge of all the parameters in the Y|X distribution.

Appendix A3. Approach 3: Constrained semiparametric MLE

This approach assumes that β is known, but does not assume that σβ is known. For this method calculation of the asymptotic variance of requires calculation of the three matrices I, C and L.

After some algebra for the situation that Y|X, B and B |X are both normal it can be shown that Thus,

which is identical to approach 2.1. ■

Derivation of asymptotic variances for the special case 2, Y, X and B binary.

Appendix B1. Standard MLE

We will be using the following notation:

The ML estimators are the solution of maximizing

In the tri-binary case, since X = X2, and B = B2, the Fisher information is

There are a total of four possible combinations of binary (X, B). Thus, the expectation terms of the matrix I(X, B) can be obtained through The asymptotic variance of is given by:

where P(BXY = 0ab) is the probability of the (B=0, X=a, Y=b) combination, and P(B = 1|XY = ab) is the probability of B=1 given X=a and Y=b, a,b∈ {0,1}.

Appendix B2. Approach 1: Synthetic data method

Motivated by the ML estimation in the missing data problem (Little, 1992), we re-formate our target likelihood as follows:

| (3) |

where f(Bi|Xi, Yi) and f(Xi, Yi) are independent from each other. The goal is to maximize likelihood 3 over γ.

Let P(XY = ab) = Pr(Xi = a, Yi = b), a, b ∈ {0,1}, i = 1,...,m+n. With the constraint there are a total of three unknown variables in Similarly, denote P(B = 1|XY = ab) = Pr(Bi = 1|Xi = a, Yi = b). i = 1,…,n. Since there are four different combination of a and b, there are four unknown parameters which are independent from each other.

By plugging the four possible combinations of X and B into model (8) in the main text, we can easily derive the expressions for γ as presented in Table 8.

Table 8:

Formulas for γ in terms of P(B|XY) and P(XY)

| (X, B) combination | transformation of model 8 |

|---|---|

| (0, 0) | |

| (1, 0) | |

| (0, 1) | |

| (1, 1) |

Let mn(a, b) denote the number of observations with (X = a, Y = b) in the sample size of m+n. Since mn(a, b) ~ Multinomial(m + n, P(XY = ab)), we can easily obtain the ML estimation of P(XY), and corresponding estimated covariance as follows:

Denote by n(a,b) as the number of observations with (X = a, Y = b) in the sample of size n, and n(B = 1|XY = ab) as the count of B =1 given (X = a, Y = b). Since n(B = 1|XY = ab) ~ Binomial(n(a, b), P(B = 1|XY = ab)), the ML estimation of P(B|X, Y) and its estimated covariance can be expressed as:

Therefore, the ML estimation of γ can be expressed as:

By the delta method, and replacing estimated proportions by the corresponding probabilities we obtain the asymptotic variances

where

Therefore, we find that the ARE of by adding m synthetic data observations compared to the original dataset of size n is

| (4) |

Appendix B3. Approach 2: Constrained MLE

The summary-level information from model (9) is available in the form of coefficient estimates β. The constrained ML estimator is the solution of maximizing subject to the constraint that

The log-likelihood can be rewritten as

From the constraints we can write θ as a function of γ in the following way

Then K becomes Denote

where j = 0, 1, 2, 3. The asymptotic variance of can be derived through the 4 × 4 matrix where

Since all Y, X and B are binary variables, there are a total of eight possible combination of (Y, X, B). Thus, the expectation term in the matrix E(uγuγT) can be obtained through

A variation on the above approach is when the external summary information comes in the form of the predicted probability for any X, i.e. we are simply provided with In these cases, it is easy to construct an estimation method that uses this as a constraint. Also in the special case being considered here where Y and X are binary, it is easy to see that knowing is equivalent to knowing so this also fits into the above framework to obtain the asymptotic variance of

Appendix B4. Approach 3: Constrained semiparametric MLE

By implementing the specific distribution into the given formulas for I, C and L, we find that I is the same as the information matrix in approach 1, that the 4×2 matrix C is the first two columns of matrix I, and that

where S = Sγ(X, B) = γ0 + γXX + γBB + γXBXB and M ≡ Mβ(X) = β0 + β1X. The calculation of L is simple under the situation where X and B are both binary. Then I, C and L can be combined to give the variance of

Although we have not written out the formulas for the ARE of for approaches 2 and 3, we find that their values are numerically identical to equation 4 with λ = 0.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Chatterjee N, Chen Y-H, Maas P & Carroll RJ (2016). Constrained maximum likelihood estimation for model calibration using summary-level information from external big data sources. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 111(513), 107–117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng W, Taylor JMG, Gu T, Tomlins SA & Mukherjee B (2019). Informing a risk prediction model for binary outcomes with external coefficient information. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series C (Applied Statistics), 68(1), 121–139. 10.1111/rssc.12306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng W, Taylor JMG, Vokonas PS, Park SK & Mukherjee B (2018). Improving estimation and prediction in linear regression incorporating external information from an established reduced model. Statistics in Medicine, 37(9), 1515–1530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estes JP & Mukherjee B & Taylor JMG (2018). Empirical Bayes estimation and prediction using summary-Level information from external big data sources adjusting for violations of transportability. Statistics in Biosciences, 10(3), 568–586. 10.1007/s12561-018-9217-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedman AN, Slattery ML, Ballard-Barbash R, Willis G, Cann BJ, Pee D, Gail MH & Pfeiffer RM(2009). Journal of Clinical Oncology, 27(5), 686–693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gail MH, Brinton LA, Byar DP, Corle DK, Green SB, Schairer C & Mulvihill JJ (1989). Projecting individualized probabilities of developing breast cancer for white females who are being examined annually. Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 81(24), 1879–1886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gourieroux C & Monfort A(1981). On the problem of missing data in linear models. Review of Economic Studies, 48(4), 579–586. [Google Scholar]

- Grill S, Fallah M, Leach RJ, Thompson IM, Hemminki K & Ankerst DP (2015). A simple-to- use method incorporating genomic markers into prostate cancer risk prediction tools facilitated future validation. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 68, 563–573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grill S and Ankerst DP and Gail MH and Chatterjee N and Pfeiffer RM (2017). Comparison of approaches for incorporating new information into existing risk prediction models. Statistics in Medicine, 36(7), 1134–1156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imbens GW & Lancaster T (1994). Combining micro and macro data in microeconometric models. The Review of Economic Studies, 61(4), 655–680. [Google Scholar]

- Little RJA (1992). Regression With Missing X’s: A Review. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 87(420), 1227–1237. [Google Scholar]

- Raghunathan TE, Reiter JP & Rubin DB (2003). Multiple imputation for statistical disclosure limitation. Journal of Official Statistics, 19(1), 1. [Google Scholar]

- Reiter JP & Kinney SK(2012). Inferentially valid, partially synthetic data: Generating from posterior predictive distributions not necessary. Journal of Official Statistics, 28(4), 583–n/a. [Google Scholar]

- Reiter JP (2002). Satisfying disclosure restrictions with synthetic data sets. Journal of Official Statistics, 18(4), 531. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin DB (1987) Multiple Imputation for Nonresponse in Surveys. John Wiley Sons Inc., New York. [Google Scholar]

- Tomlins SA and Day JR and Lonigro RJ and Hovelson DH and Siddiqui J and Kunju LP and Dunn RL and Meyer S and Hodge P and Groskopf J and Wei JT and Chinnaiyan AM (2015). Urine TMPRSS2:ERG plus PCA3 for individualized prostate cancer risk assessment. European Urology,70:45–53, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Buuren S & Oudshoom CGM (2000). MICE: Multivariate imputation by chained equations (S software for missing-data imputation).Available at web.inter.nl.net/users/S.van.Buuren/mi/. [Google Scholar]

- Xu D, Daniels MJ, and Winterstein AG (2016). Sequential BART for imputation of missing covariates. Biostatistics, 17(3):589–602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]