Abstract

Constrictive pericarditis and cardiac tamponade are two key pathologies of the pericardium. Both increase the intrapericardial pressure and cause adverse effects on the physiological distention and relaxation of the heart’s chambers. They share multiple overlapping features and, therefore, can be very challenging to differentiate between the two with regards to clinical presentation and non-invasive imaging techniques. We present a similar case with a diagnostic challenge from the laboratory investigations and non-invasive imaging. We have discussed the pathophysiology with the common and distinguishing features of the two pathologies when there is an ambiguity.

Keywords: constrictive pericarditis, pericardial tamponade, echocardiogram

Introduction

Constrictive pericarditis (CP) and pericardial tamponade are two different entities with different pathophysiology and treatment modalities. However, infrequently patients can present with comparable clinical features, equivocal electrocardiogram (ECG), and analogous echocardiogram and MRI findings. Subsequently, it may come down to invasive studies, i.e., cardiac catheterization, to differentiate between the two. We present a case in which clinical presentation, basic workup, and advanced non-invasive investigations remained inadequate to distinguish between effusive CP and pericardial tamponade.

Case presentation

A 23-year-old Indian gentleman presented with a three-week history of shortness of breath on exertion and productive cough with whitish sputum for five days. He also complained of a low-grade fever and pleuritic chest pain for one week. His past medical history was unremarkable. He had a history of alcohol intake and smoking. The patient was vitally stable, other than tachycardia (105 beats per minute). ECG showed sinus tachycardia. A chest X-ray was done, which was grossly unremarkable.

On examination, the patient had a mild decreased intensity of breath sounds over the right infrascapular area and a positive pulsus paradoxus. The rest of the physical examination was unremarkable.

A possibility of viral pericarditis with heart failure was considered, and consequently, a transthoracic echocardiogram was ordered, which showed a circumferential pericardial effusion, mainly adjacent to the right ventricle with echo signs of tamponade (Figure 1). The viral panel for common respiratory viruses was negative.

Figure 1. Red arrows: circumferential pericardial effusion (echocardiogram).

At this point, the diagnosis of pericardial tamponade was considered, and a pericardiocentesis was attempted. Approximately 100 cc of hemorrhagic fluid was aspirated and sent for analysis. The fluid was transudate and did not grow any pathogen.

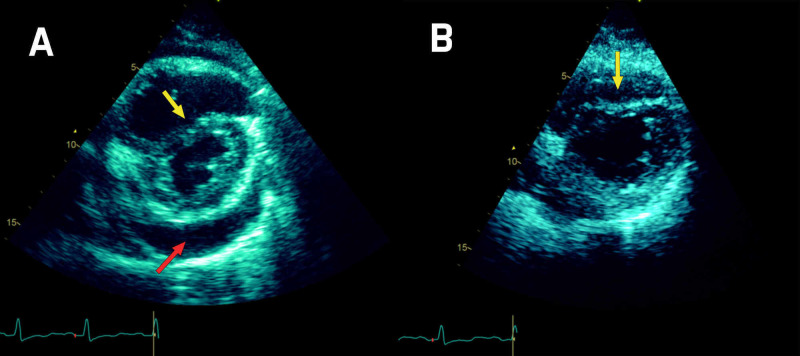

Follow-up echocardiogram revealed a septal bounce (Figure 2) and thickened pericardium. Despite the patient being admitted with pericardial tamponade, minimal fluid could be drained from the pericardium.

Figure 2. Echo short axis view: pericardial effusion and septal bounce.

(A) Pre-drainage: pericardial effusion (red arrow) and septal bounce (yellow arrow). (B) Post-drainage: persistent septal bounce (yellow arrow).

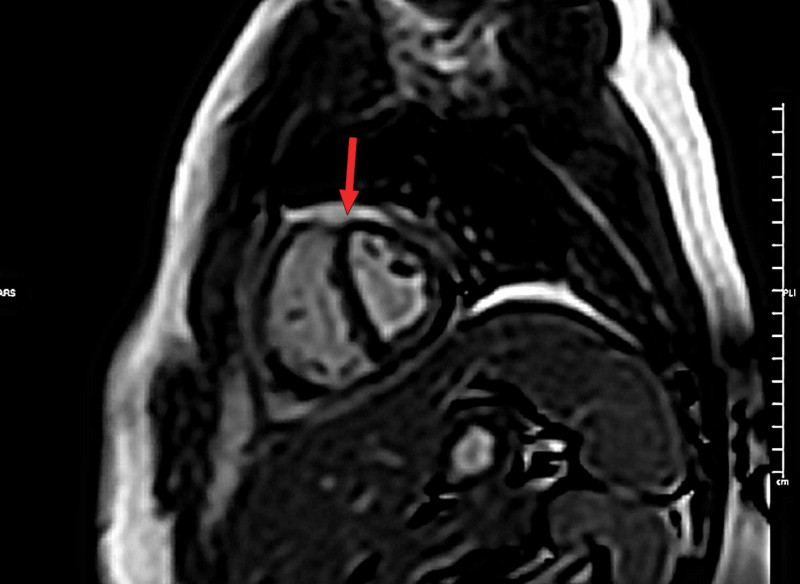

MRI of the heart showed evidence of interventricular septal bounce (Figure 3), and the late gadolinium enhancement images showed pericardial enhancement suggestive of pericarditis (Figure 4).

Figure 3. MRI short-axis view. Red arrow: septal bounce.

Figure 4. MRI short-axis view. Red arrow: septal bounce (late gadolinium enhancement).

Ultimately right heart catheterization was planned to assess the right-sided pressures and confirm the constriction hemodynamics accurately. While admitted, the patient received a course of antibiotics and ibuprofen, and he was discharged in an asymptomatic condition, with a plan of outpatient cardiac catheterization yet to be done.

Discussion

The pericardium envelopes the cardiac chambers and under physiological conditions exerts subtle functions, including mechanical effects that enhance normal ventricular interactions that contribute to balancing left and right cardiac outputs [1].

Pericardial tamponade is usually an acute or subacute condition in which fluid accumulates between the outer fibrous layer and the inner membranous layer of the pericardium. Because the pericardium is non-compliant, this build-up of fluid causes a rise in the intrapericardial pressure and hence compresses the heart. The common causes include idiopathic, infectious, autoimmune, neoplasms, and trauma.

On the other hand, CP is usually a chronic process of gradual thickening of the pericardium, causing it to lose its elasticity over time. This results in restriction of the heart to expand fully during inspiration to accommodate a venous return, thus causing a decline in pulmonary venous pressure and ultimately reduced left ventricular volume. Common causes include viral, post-radiotherapy, connective tissue disorders, and idiopathic.

CP and pericardial tamponade share many similarities in various aspects. Both can be preceded by viral infections or can be secondary to malignancies or autoimmune diseases. Pulsus paradoxus may also be seen in CP, though with a frequency less than that seen in cardiac tamponade [2]. Other mutual findings may include a raised jugular venous pressure (JVP), sinus tachycardia, and a pericardial rub.

Echo features can be strikingly congruent, for example, ventricular interdependence; the distension of the right ventricle is limited to the interventricular septum, which along with relative underfilling of the left ventricle allows the septal protrusion to the left, decreasing left ventricular compliance and leading to more reduced left ventricle loading during inspiration [3].

MRI is the best suited modality for detecting minor or confined pericardial effusions, pericardial inflammation, and functional irregularities caused by pericardial constriction and pericardial mass characterization. The wide field of view enables assessment of surrounding structures as well [4]. It allows detection of pericardial effusions with high sensitivity, demonstrating fluid collections as small as 30 mL [5]. The ultimate modality to categorically distinguish between CP and cardiac tamponade is invasive, i.e. catheterization, which is also the gold standard for the diagnosis of pericardial constriction [6]

Cardiac tamponade and CP, while having several features in common, do differ in their effect on how they alter ventricular filling. The differences stem from differences in the pattern of restriction to ventricular filling. After the drainage of pericardial fluid, the presence of annulus inversus (Figure 5) (seen in echocardiogram) is highly suggestive of CP. Furthermore, in CP restriction is limited to late diastole, while it is throughout the diastole in cardiac tamponade. This is evident by the rapid 'y' descent, 'dip & plateau' pattern, and pressure equalization during late diastole in cases of CP. On the contrary, in cases involving cardiac tamponade, pressure equalization occurs throughout the diastole. Furthermore, unrestricted thoracic pressure transmission in cardiac tamponade contributes to a retained inspiratory rise in systemic venous return (absence of the Kussmaul sign) and respiratory variability in the right atrial pressure. The preferential inspirational filling of RV, therefore, is secondary to increased filling, rather than reduced left ventricular filling seen in CP [7].

Figure 5. Classic annulus inversus suggestive of the physiology of constrictive pericarditis.

(A) Tissue Doppler pulsed wave over septal annulus of the mitral valve. (B) Tissue Doppler pulsed wave over lateral annulus of the mitral valve.

Conclusions

Although CP and cardiac tamponade are two discrete clinical conditions with respect to etiology, pathophysiology, and management, considerable similarities exist among the two. Sometimes similar clinical features and non-invasive investigations can be insufficient to single out the diagnosis, and eventually cardiac catheterization is required for the diagnostic purpose.

The content published in Cureus is the result of clinical experience and/or research by independent individuals or organizations. Cureus is not responsible for the scientific accuracy or reliability of data or conclusions published herein. All content published within Cureus is intended only for educational, research and reference purposes. Additionally, articles published within Cureus should not be deemed a suitable substitute for the advice of a qualified health care professional. Do not disregard or avoid professional medical advice due to content published within Cureus.

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Human Ethics

Consent was obtained by all participants in this study. Medical Research Center ABHATH (Doha Qatar) issued approval MRC-04-19-162. This case report was submitted in Medical Research Center, Qatar, and approval letter was obtained which is available to be presented if required

References

- 1.Cardiac tamponade, constrictive pericarditis, and restrictive cardiomyopathy. Goldstein JA. Curr Probl Cardiol. 2004;29:503–567. doi: 10.1016/j.cpcardiol.2004.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Van Dam MN, Fitzgerald BM. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2020 . Pulsus Paradoxus. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.ACC/AHA/ASE 2003 guideline update for the clinical application of echocardiography: summary article. A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines (ACC/AHA/ASE committee to update the 1997 guidelines for the clinical application of echocardiography) Cheitlin MD, Armstrong WF, Aurigemma GP, et al. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42:954–970. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(03)01065-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cardiac MRI: part 2, pericardial diseases. Rajiah P. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2011;197:621–634. doi: 10.2214/AJR.10.7265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Imaging findings in cardiac tamponade with emphasis on CT. Restrepo CS, Lemos DF, Lemos JA, et al. Radiographics. 2007;27:1595–1610. doi: 10.1148/rg.276065002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Invasive hemodynamics of constrictive pericarditis. Doshi S, Ramakrishnan S, Gupta SK. Indian Heart J. 2015;67:175–182. doi: 10.1016/j.ihj.2015.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Acute cardiac tamponade. Spodick DH. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:684–690. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra022643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]