Abstract.

Chronic Chagas disease can progress to myocardial involvement with intense fibrosis, which may predispose patients to sudden cardiac death through ventricular arrhythmia. The associations of myocardial fibrosis detected by cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) parameters with non-sustained ventricular tachycardia (NSVT) were evaluated. This cross-sectional study included patients in early stages of Chagas disease (n = 47) and a control group (n = 15). Patients underwent cardiac evaluation, including CMR examination. Myocardial fibrosis assessment by CMR with measurement of late gadolinium enhancement (LGE), native T1, and extracellular volume (ECV) was performed. There was an increase in myocardial fibrosis CMR parameters and ventricular arrhythmias among different stages of Chagas disease, combined with a decrease in the left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) by CMR and also in the right ventricular systolic function by S’ wave on tissue Doppler. Fibrosis mass and ECV were associated with the Rassi score, ventricular extrasystole, and E/e’ ratio in a logistic regression model adjusted for age and gender. The ECV maintained an association with the presence of NSVT, even after adjustments for fibrosis mass and LVEF assessed by CMR. The receiver-operating characteristic area under the curve for global ECV (0.85; 95% CI: 0.71–0.99) and NSVT was greater than that for fibrosis mass (0.75; 95% CI: 0.54–0.96), although this difference was not statistically significant. Extracellular volume could be an early marker of increased risk of ventricular arrhythmia in Chagas disease, presenting an independent association with NSVT in the initial stages of chronic Chagas cardiomyopathy, even after adjustment for fibrosis mass and LVEF.

INTRODUCTION

Chronic Chagas cardiomyopathy (CCC) is the most severe and frequent manifestation of symptomatic chronic Chagas disease that imposes a high social and economic burden.1,2 Moreover, Chagas disease has become a global health concern, mainly because of migratory movements, with non-endemic countries reporting increasing numbers of infected individuals.3

Chronic Chagas cardiomyopathy is considered an arrhythmogenic condition because of the presence of a variety of atrial or ventricular arrhythmias,4 the latter related to the risk of sudden cardiac death (SCD) even in the absence of previous significant symptoms or ventricular dysfunction. The identification of patients with increased risk of SCD is of paramount importance, particularly in earlier disease stages, allowing the implementation of preventive strategies. Currently, there is no clear recommendation for primary prevention with implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) in Chagas disease.

Nevertheless, severe ventricular dysfunction and frequent ventricular arrhythmias are known to be associated with the risk of sudden death and are present in most cases of advanced CCC.5,6 The main pathophysiological mechanism of ventricular tachyarrhythmia is related to reentrant circuits originating from fibrotic myocardial lesions. Abnormal electrical conduction occurs in areas with heterogeneous distributions of electrically inert scar tissue surrounded by gray zones with normal cardiomyocytes, which form the basis of reentrant circuits.7–9

Cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) imaging with late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) is currently the best noninvasive method for the assessment of myocardial fibrosis.10 Recent studies have demonstrated that the presence of scarring, revealed by LGE, is strongly associated with a high risk of SCD in patients with Chagas disease.11–14 However, LGE-based assessment fails to account for interstitial and diffuse collagen distribution, which leads to underestimation of the total myocardial fibrosis mass.15 New CMR techniques, such as native T1 mapping and myocardial extracellular volume (ECV) calculation, enable the quantification of diffuse myocardial fibrosis and have shown close correlation with histological findings.16,17 In a recent publication,18 the ECV was reported to be superior to LGE as a risk marker for SCD in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM); however, the ECV has not been used as a biomarker of ventricular arrhythmia risk in the context of Chagas disease.

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the associations between LGE and new CMR-derived parameters, including native T1 mapping features and ECV, with ventricular arrhythmia in patients with Chagas disease in the initial stages of chronic cardiomyopathy.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Study population.

This cross-sectional study enrolled outpatients followed at the Clinical Research Laboratory for Chagas Disease (Oswaldo Cruz Foundation, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil), and age- and gender-matched healthy controls without known cardiovascular disease between October 2017 and October 2018. Patients were of both genders and aged ≥ 18 years, had at least two positive serological test results from different methods for Trypanosoma cruzi, and had preserved or minimally reduced (≥ 45%) left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), as revealed by two-dimensional transthoracic echocardiography (TTE). Exclusion criteria were evidence of any other type of cardiomyopathy, previous infarction or coronary artery disease (CAD), more than two CAD risk factors, renal dysfunction, and contraindication for CMR imaging.

Participants were divided into four groups: controls and patients classified according to the Brazilian Consensus on Chagas disease19:

-

1.

control, healthy, and asymptomatic;

-

2.

chronic indeterminate form of Chagas disease, with no evident cardiac involvement;

-

3.

stage A of CCC, with altered electrocardiogram (ECG), but normal echocardiogram findings; and

-

4.

stage B1 of CCC, with abnormal ECG and TTE (LVEF ≥ 45%) findings.

Electrocardiogram findings were considered abnormal in the presence of complete or incomplete (≥ second degree) bundle-branch block, second- or third-degree atrioventricular block, mono or polymorphic ventricular extrasystole, non-sustained ventricular tachycardia (NSVT), primary repolarization alterations, or abnormal Q waves.

The research was conducted according to the precepts of the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by the local ethics committee (Research Ethics Committee of the Evandro Chagas National Institute of Infectious Diseases, Oswaldo Cruz Foundation). All patients have provided written informed consent to publication.

Sample size.

Sample size calculation was based on the study published by Siepen et al.,20 in which an absolute difference of 4.0% for the ECV was estimated between groups with and without dilated heart disease, with an SD of 4.0% for each group. Considering 80% power and 5% significance level, a total of 60 subjects (15 per group) were required for the present study.

Routine investigations and measurements.

Patients underwent the clinical examination, 12-lead ECG, chest X-ray, and 24-hour electrocardiographic Holter monitoring at the first visit and then were classified according to the New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class and the Rassi score.5 Two-dimensional transthoracic echocardiography was performed on the following day, whereas hematocrit measurement and CMR were performed approximately 2 weeks thereafter.

Holter monitoring was performed with a digital recorder (Mortara H3+™, Milwaukee, WI) to observe the basal rhythm, atrioventricular conduction pattern, numbers of premature complexes, and presence of ventricular and supraventricular tachycardia. Two-dimensional TTE examinations were performed by the same experienced professional, who was blinded to clinical classification, using a Vivid 7 equipment (General Electric Medical Systems®, Milwaukee, WI). All TTE measurements were acquired in accordance with the European and American recommendations.21

Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging protocol.

All subjects underwent CMR imaging performed with a 3.0-T scanner (Magnetom Prisma; Siemens AG, Erlangen, Germany). Cine images were acquired in long- and short-axis planes. T1 mapping images were obtained in a mid-ventricular short-axis plane using the Modified Look-Locker Inversion (MOLLI) recovery sequence before and 15 minutes after contrast infusion. The 5(3)3 MOLLI sequence design22 was used for pre-contrast (native) T1 mapping, whereas the 4(1)3(1)2 design was used for post-contrast acquisition.23 LGE images were acquired 10 minutes after contrast infusion with a breath-hold segmented gradient-recalled echo inversion recovery sequence.

Cardiac magnetic resonance image analysis.

Images were analyzed in a blinded fashion using multi-platform commercial software (OsiriX MD; Pixmeo, Geneva, Switzerland). Myocardial T2 and pre- and post-contrast T1 were quantified directly on T2 and T1 mapping images, respectively, using the mean signal intensity value from a region of interest (ROI) drawn manually to cover the entire left ventricular myocardium. In addition, a 2-cm2 circular ROI was placed in the center of the left ventricular cavity on T1 maps to determine pre- and post-contrast blood pool T1 values for ECV calculation. Myocardial LGE mass was quantified using the visual semiquantitative score approach.24 The extent of LGE was determined in each of the 17 myocardial segments on short-axis LGE images and recorded using a 5-point scoring scheme. This quantification technique was chosen for the following reasons: 1) it is straightforward, 2) shows a high degree of agreement with the manual planimetric method,25,26 3) has lower inter- and intra-rater variability than the pixel-wise signal intensity semi-automatic method,27 and 4) avoids a main limitation of the latter, namely, the lack of consensus on an ideal threshold for fibrosis detection.

Data analysis.

The Research Electronic Data Capture web application was used for data management, and Stata software version 13.0 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX) was used for the statistical analysis. Patient characteristics were expressed as means (SDs) or percentages (absolute frequencies). A nonparametric test of trend for the ranks was used to compare differences between groups (ntrend in Stata).

Associations between exposure variables and outcomes were examined using multinomial or binomial logistic and linear regression models. Models were adjusted for age and gender, and those for the ECV were further adjusted for fibrosis mass and LVEF assessed by CMR. The ability of logistic regression models to predict NVST was evaluated using a receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) curve. The areas under the curve (AUCs), sensitivity, and specificity were calculated. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05 for all analyses.

RESULTS

This study included a total of 62 subjects: 47 patients with Chagas disease and 15 controls. Twenty-one (44.7%) patients were male, and the mean patient age was 58.6 ± 10.4 years. All demographic characteristics were similar between patients and controls (Table 1). Thirty-eight (80.8%) patients reported no symptom, eight (17%) had palpitations, four (8.5%) had histories of typical vasovagal syncope, and one (2.1%) reported atypical precordial pain with the exclusion of obstructive coronary disease. Five (10.6%) patients from group 3 or 4 had chronic digestive Chagas disease. All individuals were in NYHA class I. The only cardiovascular medications used were antihypertensive agents, statins, and oral hypoglycemic agents. As the patients did not present heart failure or systolic dysfunction, neurohumoral blockade was not indicated.

Table 1.

Characteristics of participants included in the study stratified by Chagas disease clinical presentation

| Clinical assessment | Control (n = 15) | Chronic indeterminate form (n = 16) | Cardiac A (n = 15) | Cardiac B1 (n = 16) | P-value (for trend) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 54.8 (±12.6) | 57.9 (±12.2) | 57.7 (±11.0) | 60.0 (±8.3) | 0.22 |

| Male gender | 8 (53.3) | 5 (31.3) | 8 (53.3) | 8 (50.0) | 0.82 |

| Cardiac magnetic resonance | |||||

| LV end diastolic volume (ml) | 131.1 (±19.9) | 141.8 (±35.1) | 136.6 (±38.3) | 154.3 (±46.1) | 0.21 |

| LV end systolic volume (ml) | 38.1 (±9.0) | 45.1 (±21.7) | 43.1 (±14.3) | 71.0 (±38.6) | 0.001 |

| LVEF (%) | 71.2 (±3.6) | 69.5 (±6.8) | 68.4 (±5.2) | 55.9 (±10.8) | < 0.001 |

| WMSI | 1 (±0) | 1.06 (±0.25) | 1.02 (±0.06) | 1.52 (±0.43) | < 0.001 |

| Presence of LGE | 0.0 (0) | 7 (43.8) | 6 (40.0) | 15 (93.8) | < 0.001 |

| Subendocardial LGE | – | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | – |

| Meso- or epicardial LGE | – | 7 (43.8) | 6 (40.0) | 14 (87.5) | 0.01 |

| Transmural LGE | – | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 6 (37.7) | 0.002 |

| Percentage of LGE (%) | – | 4.4 (±3.9) | 6.5 (±4.7) | 13.6 (±12.3) | 0.01 |

| Myocardial native T1 (ms) | 1,213.7 (±28.1) | 1,225.0 (±40.4) | 1,219.3 (±27.8) | 1,268.4 (±61.6) | 0.003 |

| T2 (ms) | 42.2 (±4.1) | 43.9 (±2.8) | 41.5 (±2.0) | 44.2 (±3.1) | 0.35 |

| ECV (%) | 24.6 (±1.7) | 25.8 (±2.6) | 25.8 (±2.5) | 29.5 (±3.8) | < 0.001 |

| Fibrosis mass (g) | 0.0 (0.0) | 1.99 (4.30) | 3.35 (5.64) | 15.7 (17.09) | < 0.001 |

| RVEF (%) | 68.0 (±4.0) | 68.0 (±6.0) | 68.2 (±5.4) | 62.6 (±7.6) | 0.06 |

| Holter/echocardiography | |||||

| PVC (presence vs. absence) | – | 7 (43.8) | 11 (73.3) | 16 (100) | < 0.001 |

| Number of isolated PVC* | – | 24.3 (±24.8) | 889.0 (±1395.9) | 3,380.5 (±6905.7) | < 0.001 |

| NSVT (presence vs. absence) | – | 0 (0) | 1 (6.7) | 7 (43.8) | 0.001 |

| LVEDV (mL) | – | 93.9 (±30.5) | 90.4 (±13.4) | 106.2 (±26.3) | 0.06 |

| LVESV (mL) | – | 34.4 (±13.8) | 31.6 (±6.9) | 43.9 (±16.6) | 0.05 |

| LVEF (%) | – | 65.1 (±5.0) | 65.1 (±5.8) | 60.8 (±8.4) | 0.08 |

| E/e’ ratio | – | 8.5 (±2.7) | 7.7 (±2.6) | 11.3 (±5.7) | 0.09 |

| RV S’ | – | 12.3 (±1.7) | 12.4 (±1.5) | 11.0 (±1.5) | 0.04 |

Values are n (%) or mean (±SD). ECV = extracellular volume; LGE = late gadolinium enhancement; LV = left ventricular; LVEDV = left ventricular end diastolic volume; LVESV = left ventricular end systolic volume; LVEF = left ventricular ejection fraction; NSVT = non-sustained ventricular tachycardia; PVC = premature ventricular contraction; RVEF = right ventricular ejection fraction; RV S’ = right ventricular S’ wave on tissue Doppler; WMSI = wall motion score index.

Assessed by 24-hour Holter monitoring.

On 24-hour Holter monitoring, the number of ventricular extrasystoles increased progressively with the disease stage. The frequency of ventricular extrasystole and NSVT was increased in patients with B1 CCC. There was a decrease in the LVEF measured by CMR among different stages of Chagas disease; however, the LVEF did not differ significantly when evaluated by echocardiography, presumably because of the higher sensitivity of CMR. There was no difference in right ventricular ejection fraction evaluated by CMR, whereas there was a decrease in right ventricular systolic function by S’ wave on tissue Doppler (P = 0.04). Regional wall motion abnormalities were evaluated by CMR, and wall motion score index was higher in B1 group (P < 0.001).

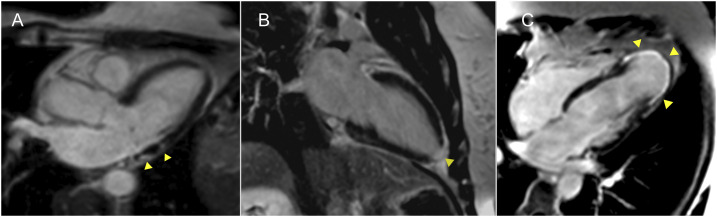

There was an increase in myocardial fibrosis CMR parameters among different stages of Chagas disease. The frequency of focal fibrosis evaluated by LGE increased progressively with the disease stage (Table 1). No patient demonstrated isolated subendocardial LGE. Meso-epicardial LGE was detected similarly in patients with indeterminate (43.8%) and stage A (40%) disease and was more frequent in patients with B1 CCC (87.5%). Transmural LGE was evidenced only in patients with B1 disease (37.7%). Typical observed patterns of myocardial LGE are illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Typical observed patterns of myocardial LGE. Images from three patients with LGE depicting the most common scar patterns (arrowheads). (A) Meso-epicardial LGE in the left ventricular lateral wall. (B) Transmural LGE involving the left ventricular apex. (C) Transmural LGE involving all left ventricular apical segments with aneurism formation. LGE = late gadolinium enhancement. This figure appears in color at www.ajtmh.org.

Fibrosis mass (LGE) was associated with the following outcomes in the age- and gender-adjusted logistic regression model: B1 cardiac stage, intermediate–high Rassi score, presence of ventricular extrasystoles, and the E/e’ ratio. The left ventricular ejection fraction measured by CMR was correlated inversely with the right ventricular S’ wave measured by tissue Doppler echocardiography (Table 2).

Table 2.

Association between fibrosis mass and clinical outcomes (n = 47)

| Outcome | Fibrosis mass | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multinomial logistic regression* | ||||

| Non-adjusted RRR (95% CI) | P-value | Adjusted age/gender RRR (95% CI) | P-value | |

| Clinical form: cardiac A | 1.08 (0.90 to 1.30) | 0.38 | 1.07 (0.89 to 1.29) | 0.47 |

| Clinical form: cardiac B1 | 1.24 (1.04 to 1.49) | 0.02 | 1.27 (1.05 to 1.54) | 0.02 |

| Binomial logistic regression | ||||

| Non-adjusted OR (95% CI) | P-value | Adjusted age/gender OR (95% CI) | P-value | |

| Rassi score: intermediate and high | 1.07 (1.00 to 1.14) | 0.03 | 1.07 (1.00 to 1.14) | 0.05 |

| PVC (presence vs. absence) | 2.06 (1.10 to 3.87) | 0.02 | 2.06 (1.04 to 4.10) | 0.04 |

| NSVT (presence vs. absence) | 1.04 (0.99 to 1.10) | 0.12 | 1.05 (0.99 to 1.12) | 0.08 |

| Linear regression | ||||

| Non-adjusted Β (95% CI) | P-value | Adjusted age/gender Β (95% CI) | P-value | |

| LVEF—CMR | −0.67 (−0.81 to −0.53) | < 0.001 | −0.65 (−0.79 to −0.50) | < 0.001 |

| Number of PVC† | +19.25 (−111.57 to +150.09) | 0.76 | +47.46 (−90.69 to +185.59) | 0.48 |

| E/e’ ratio | +0.20 (+0.13 to +0.29) | < 0.001 | +0.22 (+0.14 to +0.30) | < 0.001 |

| RV S’ | −0.04 (−0.08 to −0.008) | 0.02 | −0.05 (−0.09 to −0.005) | 0.03 |

CMR = cardiac magnetic resonance; LVEF = left ventricular ejection fraction; NSVT = non-sustained ventricular tachycardia; OR = odds ratio; PVC = premature ventricular contraction; RRR = relative risk reduction; RV S’ = right ventricular S’ wave on tissue Doppler.

Indeterminate group was used as reference.

Assessed by 24-hour Holter monitoring.

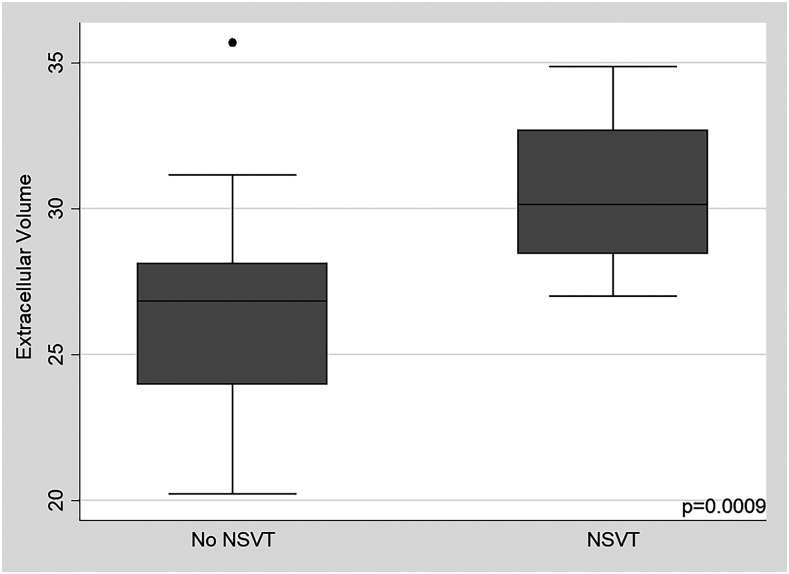

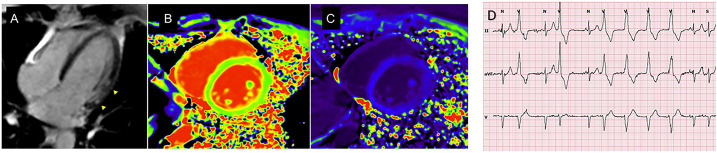

Similar results were observed for the myocardial ECV and native T1. When this model was adjusted according to fibrosis mass, the significance of the Rassi score, presence of ventricular extrasystoles, E/e’ ratio, and right ventricular S’ wave were lost. Significance was maintained only for the LVEF and presence of ventricular tachycardia (Table 3). Moreover, after adjusting for the LVEF detected by CMR, the ECV remained associated with NSVT (P = 0.02). Figure 2 demonstrates differences in ECV values between patients with and without NSVT (P = 0.0009). An example of a patient with altered CMR parameters and NSVT is shown in Figure 3.

Table 3.

Association between extracellular volume and clinical outcomes (n = 47)

| Outcome | Extracellular volume | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multinomial logistic regression* | ||||

| Non-adjusted RRR (95% CI) | P-value | Adjusted modelis† RRR (95% CI) | P-value | |

| Clinical form: cardiac A | 0.96 (0.75 to 1.23) | 0.73 | 0.95 (0.70 to 1.29) | 0.75 |

| Clinical form: cardiac B1 | 1.53 (1.12 to 2.08) | 0.008 | 1.30 (0.89 to 1.90) | 0.17 |

| Binomial logistic regression | ||||

| Non-adjusted OR (95% CI) | P-value | Adjusted model OR (95% CI) | P-value | |

| Rassi score: intermediate and high | 1.40 (1.07 to 1.81) | 0.01 | 1.35 (0.95 to 1.90) | 0.09 |

| PVC (presence vs. absence) | 1.38 (1.08 to 1.78) | 0.01 | 1.12 (0.77 to 1.62) | 0.55 |

| NSVT (presence vs. absence) | 1.56 (1.13 to 2.17) | 0.007 | 1.80 (1.13 to 2.87) | 0.01 |

| Linear regression | ||||

| Non-adjusted Β (95% CI) | P-value | Adjusted model Β (95% CI) | P-value | |

| LVEF—CMR | −1.83 (−2.49 to −1.17) | < 0.001 | −0.84 (−1.47 to −0.20) | 0.01 |

| Number of PVC‡ | +142.5 (−397.8 to 682.8) | 0.60 | +30.3 (−731.6 to +792.2) | 0.94 |

| E/E’ ratio | +0.54 (+0.22 to +0.86) | 0.001 | −0.006 (−0.38 to +0.37) | 0.97 |

| RV S’ | −0.14 (−0.28 to −0.006) | 0.04 | −0.08 (−0.27 to +0.11) | 0.40 |

B = β coefficient; CMR = cardiac magnetic resonance; LVEF = left ventricular ejection fraction; NSVT = non-sustained ventricular tachycardia; OR = odds ratio; PVC = premature ventricular contraction; RRR = relative risk reduction; RV S’ = right ventricular S’ wave on tissue Doppler.

Indeterminate group was used as reference.

Adjusted model includes gender, age, and fibrosis mass as covariates.

Assessed by 24-hour Holter monitoring.

Figure 2.

Extracellular volume values among participants with and without NSVT. NSVT = non-sustained ventricular tachycardia.

Figure 3.

Extracellular volume, native T1, and LGE were associated with ventricular arrhythmia in the initial stages of chronic Chagas cardiomyopathy. A 50-year-old patient presenting mesocardial LGE in the left ventricular lateral wall (arrowheads in A), a longer native T1 of 1,291 ms, an elevated ECV of 32% (B and C), and NSVT on 24-hour Holter monitoring (D). ECV = extracellular volume; LGE = late gadolinium enhancement; NSVT = non-sustained ventricular tachycardia. This figure appears in color at www.ajtmh.org.

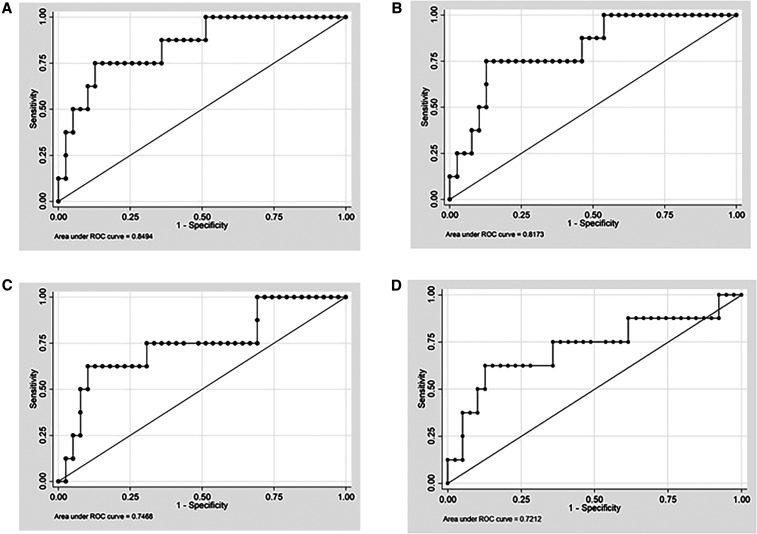

In the ROC curve analysis, the myocardial ECV showed good accuracy for the identification of NSVT, with an AUC of 0.85 (95% CI: 0.71–0.99; Figure 4). Similar associations were detected between native myocardial T1 and NSVT (AUC: 0.81; 95% CI: 0.65–0.97) and also between fibrosis mass (LGE) and NSVT (AUC = 0.75; 95% CI: 0.54–0.96), with no statistically significant differences between the models (P = 0.26). Wall motion score index had the lower AUC for NSVT identification (AUC: 0.72; 95% CI: 0.48–0.95), although not significantly different from the ECV (P = 0.22).

Figure 4.

Receiver-operating characteristic curves for associations of ECV, native T1, and fibrosis mass with NSVT. ROC curves and corresponding AUC statistics for associations between NSVT and the ECV (A), native T1 (B), fibrosis mass (C), and WMSI (D). AUC = area under the curve; ECV = extracellular volume; ROC = receiver-operating characteristic; NSVT = non-sustained ventricular tachycardia; WMSI = wall motion score index. Models are adjusted for gender and age.

The cutoff points of greatest accuracy for NSVT prediction obtained from the ROC curve analysis were 28.0% for the myocardial ECV and 1258 ms for native myocardial T1, with a sensitivity of 75% for both and specificities of 85% and 79%, respectively.

DISCUSSION

To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to use native T1 and the ECV to quantify interstitial fibrosis in patients with Chagas disease, evaluating the associations of these values with ventricular arrhythmia. Our findings demonstrated that myocardial ECV was independently associated with NSVT, even after adjustments for fibrosis mass (LGE) and the LVEF.

The presence of ventricular arrhythmia has been considered a reliable surrogate for SCD, an important cause of death related to Chagas disease even in patients with preserved left ventricular function.28,29 Sudden cardiac death related to Chagas disease is an underdiagnosed event because malignant ventricular arrhythmias may mimic acute coronary syndrome.30 The pathophysiology of ventricular arrhythmia is related to scar and fibrotic tissues, described as substrates for reentry.7 Recent studies using LGE in CMR imaging showed that the presence of myocardial fibrosis was a marker of the risk of such arrhythmia in patients with HCM, CAD, dilated cardiomyopathy, and valvar, congenital, and other nonischemic heart diseases, including Chagas disease.18

As LGE-based assessment depends on the heterogeneous and coalescent distribution of myocardial collagen content for the identification of areas of fibrosis,10,12 it fails to account for interstitial and more diffuse distribution in some cases, which leads to the underestimation of the total myocardial fibrosis mass. Myocardial T1 mapping and, particularly, ECV calculation enable the identification of areas of increased myocardial collagen content, regardless of its distribution pattern, and have shown high degrees of correlation with the histological assessment of interstitial fibrosis.20

Extracellular volume was reported to be superior to all tested clinical and CMR parameters for the identification of patients with HCM at increased risk of SCD, including LGE.18 Although the ECV is considered to be more sensitive than LGE for the estimation of the myocardial collagen concentration in patients with various diseases, it has not been evaluated in patients with CCC, in which mortality is strongly associated with left ventricular dysfunction and heart failure.29 Rassi et al.5 established a scoring system with six independent prognostic factors to estimate the all-cause mortality risk in patients with Chagas disease, but studies examining the risk of SCD specifically are lacking. Recently, our group proposed a risk score for the prediction of sudden death in these patients, which included four independent clinical variables: QT interval dispersion, premature ventricular complexes, severe left ventricular dysfunction, and syncope.6 After 5.5 years of follow-up, low-, moderate-, and high-risk groups presented SCD rates of 1.5%, 25%, and 51%, respectively. Unfortunately, this score was not externally validated, and QT interval dispersion measurements lack standardization and have poor reproducibility.

Although SCD is more common in patients with Chagas disease with advanced left ventricular dysfunction, Tassi et al.9 demonstrated that electrical instability can be present and associated with myocardial fibrosis (LGE) even in patients with preserved or minimally impaired ventricular function, reinforcing the importance for the early identification of individuals at risk. Our population comprised subjects with relatively preserved (≥ 45%) LVEF, no relevant symptom of arrhythmia, and NYHA functional class I, including those with the indeterminate chronic stage and early stages of cardiac forms of Chagas disease (A and B1). Nonetheless, ventricular extrasystoles were frequent with the progression of disease severity, being present in all patients in B1 stage. Similar to Tassi et al.,9 we observed the presence of LGE in a low-risk population, including patients with the chronic indeterminate form of Chagas disease. Fibrosis mass (LGE) increased progressively with the disease severity, and meso-epicardial LGE was the most prevalent pattern, present in around 40% of patients with the chronic indeterminate and A stages, and in 87.5% of those with B1 stage. On the other hand, the transmural pattern was detected only in patients with B1 (37.7%). In contrast to a recent publication,11 we did not observe the isolated subendocardial LGE pattern. These discrepant results can be explained by differences in the characteristics of study population because we excluded patients with possible CAD and reduced (< 45%) LVEFs, whereas Senra et al.’s population had a mean LVEF of 43.3%, and 5.4% evidenced the subendocardial pattern.

In 2016, Uellendahl et al.31 published the first study of CMR quantification of myocardial fibrosis and provided prognostic data for patients with Chagas disease. They demonstrated a strong correlation between the extent of myocardial fibrosis (LGE) and the Rassi score (r = 0.76), used to predict all-cause mortality. This finding was validated in recent longitudinal studies that evaluated the value of myocardial fibrosis (LGE) for the prediction of outcomes such as cardiovascular death and sustained ventricular tachycardia.11,13 These reports suggest that the prognostic value of LGE adds to the risk stratification obtained with the clinical Rassi score,5 possibly improving the selection of patients for ICD.

The C statistic for the ECV and fibrosis mass for the identification of NSVT were similar; however, after adjustments for fibrosis mass and LVEF, the ECV was the only variable associated with NSVT. Regardless, ROC curve analysis indicated a high accuracy for the ECV and native T1 in the prediction of NSVT.

The present study has some limitations. The sample included in this study was relatively small, even though a priori calculation indicated adequate power (80%) to identify ECV differences between patients with and without dilated heart disease.20 In addition, the cross-sectional design precludes us to establish a causal pathway, although it is useful to raise hypotheses that should be confirmed in future longitudinal studies with hard outcomes. The small number of total events may be explained by the inclusion of patients in the initial CCC stages, which may have decreased the statistical power and increased the risk of overfit.

Extracellular volume showed an independent association with NSVT in the initial stages of CCC, even with adjustment for fibrosis mass and LVEF. Prospective studies are necessary to confirm if ECV would be an early marker of increased risk of ventricular arrhythmia in Chagas disease that could help us to make rational, data-based decisions regarding primary prevention ICD implantation.

REFERENCES

- 1.WHO , 2015. Chagas disease in Latin America: an epidemiological update based on 2010 updates. Wkly Epidemiol Rec 90: 33–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rassi A, Jr., Rassi A, Marin-Neto JÁ, 2010. Chagas disease. Lancet 375: 1388–1402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Antinori S, Galimberti L, Bianco R, Grande R, Galli M, Corbellino M, 2017. Chagas disease in Europe: a review for the internist in the globalized world. Eur J Int Med 43: 6–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maguire JH, Hoff R, Sherlock I, Guimarães AC, Sleigh AC, Ramos NB, Mott K, Weller TH, 1987. Cardiac morbidity and mortality due to Chagas disease: prospective electrocardiographic study of a Brazilian community. Circulation 75: 1140–1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rassi A, Jr., Rassi A, Little WC, Xavier SS, Rassi SG, Rassi AG, Rassi GG, Hasslocher-Moreno A, Sousa AS, Scanavacca MI, 2006. Development and validation of a risk score for predicting death in Chagas’ heart disease. N Engl J Med 355: 799–808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Souza AC, Salles G, Hasslocher-Moreno AM, do Brasil PEA, Saraiva RM, Xavier SS, 2015. Development of a risk score to predict sudden death in patients with Chagas’ heart disease. Int J Cardiol 187: 700–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rossi MA, 1991. The pattern of myocardial fibrosis in chronic Chagas’ heart disease. Int J Cardiol 30: 335–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baroldi G, Oliveira SJ, Silver MD, 1997. Sudden and unexpected death in clinically silent’ Chagas disease. A hypothesis. Int J Cardiol 58: 263–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tassi EM, Continentino MA, Nascimento EM, Pereira BB, Pedrosa RC, 2014. Relationship between fibrosis and ventricular arrhythmias in Chagas heart disease without ventricular dysfunction. Arq Bras Cardiol 102: 456–464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rochitte CE, Nacif MS, Oliveira AC, Jr., Siqueira-Batista R, Marchiori E, Uellendahl M, Higuchi ML, 2007. Cardiac magnetic resonance in Chagas’ disease. Artif Organs 31: 259–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Senra T, Ianni BM, Costa AC, Mady C, Martinelli-Filho M, Kalil-Filho R, Rochitte CE, 2018. Long-term prognostic value of myocardial fibrosis in patients with Chagas cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol 72: 2577–2587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rochitte CE, et al. 2005. Myocardial delayed enhancement by magnetic resonance imaging in patients with Chagas’ disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 46: 1553–1558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Volpe GJ, et al. 2018. Left ventricular scar and prognosis in chronic Chagas cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol 72: 2567–2576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Disertori M, Rigoni M, Pace N, Casolo G, Masè M, Gonzini L, Lucci D, Nollo G, Ravelli F, 2016. Myocardial fibrosis assessment by LGE is a powerful predictor of ventricular tachyarrhythmias in ischemic and nonischemic LV dysfunction: a meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol Img 9: 1046–1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Torreão JA, et al. 2015. Myocardial tissue characterization in Chagas’ heart disease by cardiovascular magnetic resonance. J Cardiovasc Magn Reason 17: 97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mewton N, Liu CY, Croisille P, Bluemke D, Lima JAC, 2011. Assessment of myocardial fibrosis with cardiac magnetic resonance. J Am Coll Cardiol 57: 891–903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kammerlander AA, et al. 2016. T1 Mapping by CMR imaging: from histological validation to clinical implication. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 9: 14–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Avanesov M, et al. 2017. Prediction of the estimated 5-year risk of sudden cardiac death and syncope or non-sustained ventricular tachycardia in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy using late gadolinium enhancement and extracellular volume CMR. Eur Radiol 27: 5136–5145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dias JCP, et al. 2016. Brazilian consensus on chagas disease 2015. Epidemiol Serv Saúde 25: 7–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.aus dem Siepen F, et al. 2015. T1 mapping in dilated cardiomyopathy with cardiac magnetic resonance: quantification of diffuse myocardial fibrosis and comparison with endomyocardial biopsy. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 16: 210–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mitchell C, Rahko PS, Blauwet LA, Canaday B, Finstuen JA, Foster MC, Horton K, Ogunyankin KO, Palma RA, Velazquez EJ, 2019. Guidelines for performing a comprehensive transthoracic echocardiographic examination in adults: recommendations from the American society of echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 32: 1–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kellman P, Arai AE, Xue H, 2013. T1 and extracellular volume mapping in the heart: estimation of error maps and the influence of noise on precision. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 15: 56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schelbert EB, et al. 2011. Myocardial extravascular extracellular volume fraction measurement by gadolinium cardiovascular magnetic resonance in humans: slow infusion versus bolus. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 13: 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fine NM, Tandon S, Kim HW, Shah DJ, Thompson T, Drangova M, White JA, 2013. Validation of sub-segmental visual scoring for the quantification of ischemic and nonischemic myocardial fibrosis using late gadolinium enhancement CMR. J Magn Reson Imaging 38: 1369–1376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Doesch C, Huck S, Böhm CK, Michaely H, Fluechter S, Haghi D, Dinter D, Borggrefe M, Papavassiliu T, 2010. Visual estimation of the extent of myocardial hyperenhancement on late gadolinium-enhanced CMR in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Magn Reson Imaging 28: 812–819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Klem I, Heiberg E, Van Assche L, Parker MA, Kim HW, Grizzard JD, Arheden H, 2017. Sources of variability in quantification of cardiovascular magnetic resonance infarct size - reproducibility among three core laboratories. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 19: 62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gräni C, et al. 2019. Comparison of myocardial fibrosis quantification methods by cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging for risk stratification of patients with suspected myocarditis. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 21: 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xavier SS, de Sousa AS, do Brasil PEAA, Gabriel FG, Holanda MT, Hasslocher-Moreno A, Garcia MY, Siciliano APRV, 2005. Incidence and predictors of sudden death in chronic Chagas cardiomyopathy with preserved systolic function. Rev SOCERJ 18: 457–463. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rassi A, Jr., Rassi A, Rassi SG, 2007. Predictors of mortality in chronic Chagas disease: a systematic review of observational studies. Circulation 115: 1101–1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moll-Bernardes RJ, et al. 2020. Case report: malignant ventricular arrhythmias mimicking acute coronary syndrome in chagas disease. Am J Trop Med Hyg 102: 797–799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Uellendahl M, de Siqueira MEM, Calado EB, Kalil-Filho R, Sobral D, Ribeiro C, Oliveira W, Martins S, Narula J, Rochitte CE, 2016. Cardiac magnetic resonance-verified myocardial fibrosis in chagas disease: clinical correlates and risk stratification. Arq Bras Cardiol 107: 460–466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]