SUMMARY:

Medullary edema with enhancement is rarely reported at initial MR imaging in intracranial dural arteriovenous fistulas. We report a series of 5 patients with dural arteriovenous fistulas, all of whom demonstrated a characteristic pattern of central medullary edema and medullary enhancement at initial MR imaging. Cognard type V dural arteriovenous fistula, defined by drainage into the perimedullary veins and the veins surrounding the brain stem, is a rare yet well-described pathologic entity. Even more rarely reported, however, is its clinical presentation with predominantly bulbar symptoms and MR imaging findings of central medullary edema with enhancement. This constellation of findings frequently leads to a convoluted clinical picture, prompting work-up for alternative disease processes and delaying diagnosis. Because an expedited diagnosis is critical in preventing poor outcomes, it is paramount to make the referring physician and neuroradiologist more cognizant of this rare-yet-characteristic imaging manifestation of dural arteriovenous fistula.

Intracranial dural arteriovenous fistulas (DAVFs) result from a meshwork of anomalous communications between dural arteries and dural venous sinuses or cortical veins, without an intervening capillary network or nidus, and account for approximately 10%–15% of intracranial vascular malformations.1 The rare Cognard type V DAVF is defined by its drainage into veins around the brain stem and further caudally into the perimedullary veins.2 Consequently, this subtype often presents with symptoms related to swelling of the cervical cord, including a slowly progressive myelopathy initially involving the upper limbs. The imaging findings include an enlarged cervical cord and engorged perimedullary veins.

What is less commonly understood and described here is the clinical presentation with bulbar symptoms related to brain stem involvement.3 The imaging findings within the brain stem are even more rarely reported, though intuitively, a brain MR may be the initial imaging test ordered by clinicians in these patients. MR imaging may reveal central medullary edema with occasional intense medullary enhancement.4 Engorged perimedullary veins may not be evident. These findings may lead the clinician further astray and prompt a work-up for a neoplasm and infectious or inflammatory processes. Ultimately, improper management and, in some reported instances, biopsy for a suspected neoplasm may occur.5

We report a series of 5 patients who presented at 2 nearby academic institutions from 2012 to 2016 with DAVFs demonstrating medullary edema and enhancement at initial imaging. Most interesting, the unique pattern of edema was nearly identical in all 5 cases and, retrospectively, has been anecdotally mentioned previously.5–7 All 5 patients underwent CT and MR imaging examinations, and 2 patients underwent MR spectroscopy/perfusion because there was concern for a neoplasm. All patients eventually underwent conventional angiography.

This multicenter retrospective study was approved by the institutional review board of each institution with data compiled into a single Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act–compliant data base.

Cases

Case 1.

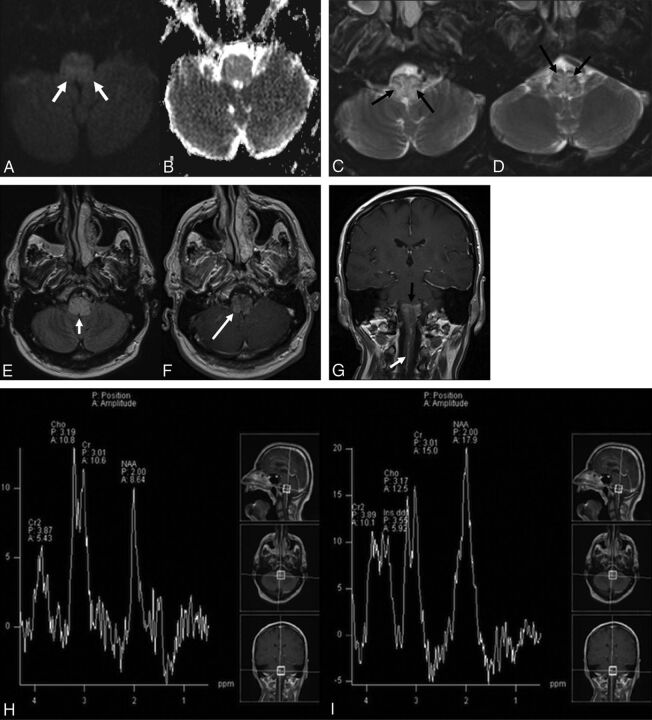

A 59-year-old man presented with new-onset dizziness and severe nausea and vomiting. He reported positional vertigo that had commenced 5 weeks before presentation. MR imaging revealed a relatively diffuse T2 hyperintense signal within the medulla, with peripheral and internal linear areas of sparing, as well as associated mild medullary enhancement (Fig 1A–F). CTA was also performed, and no vascular malformation was identified. MR imaging with spectroscopy/perfusion was performed several days later to exclude neoplasms (Fig 1G–J). This repeat MR imaging demonstrated prominent vessels along the surface of the medulla and upper cervical cord (Fig 1G). Spectroscopy did not reveal findings concerning for an aggressive neoplasm, and MR perfusion demonstrated decreased relative cerebral blood volume (Fig 1J) and flow within the medulla. Concern was raised for a potential DAVF, and catheter angiography was recommended. Angiography revealed a DAVF in the wall of the left superior petrosal sinus (Fig 1K, -L). The patient underwent a combination of endovascular embolization and surgical resection of the DAVF, and repeat angiography showed no recurrence. His symptoms markedly improved with no recurrence at 3-year follow-up.

Fig 1.

A 59-year-old man who presented with new-onset dizziness and severe nausea and vomiting. Initial MR imaging demonstrates mild hyperintense signal on axial DWI (b = 1000) (white arrows, A) without definite restricted diffusion on the corresponding ADC map (B). There is relatively diffuse hyperintense signal abnormality within the medulla on axial T2WI with fat suppression (C and D) with sparing of the periphery and several internal linear regions (black arrows). This pattern of sparing was not initially recognized. E, Axial FLAIR imaging demonstrates relatively diffuse hyperintense signal abnormality within the medulla (short white arrow). Axial postcontrast T1WI (F) demonstrates mild patchy enhancement (long white arrow). G, Coronal postcontrast T1WI reveals a dilated perimedullary vein (white arrow) extending inferiorly from the patchy enhancement within the medulla (black arrow) and coursing caudally along the upper cervical cord. MR spectroscopy with TEs of 135 (H) and 35 (I) ms demonstrates no significant elevation in choline with decreased NAA. MR perfusion imaging (J) reveals slightly decreased relative CBV within the medulla. Suspicion was raised for an underlying DAVF. Left external carotid injection on digital subtraction angiography arterial phase lateral (K) and delayed venous phase anteroposterior (L) views demonstrates a DAVF in the wall of the left superior petrosal sinus (long white arrow) fed by meningeal branches of the occipital (short white arrow), ascending pharyngeal (long black arrow), and middle meningeal (short black arrows) arteries, with retrograde venous drainage via the petrosal vein to the pial perimedullary veins running to the cervical cord as the anterior and posterior spinal veins (black dashed arrows).

Case 2.

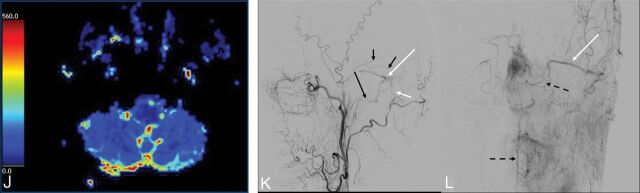

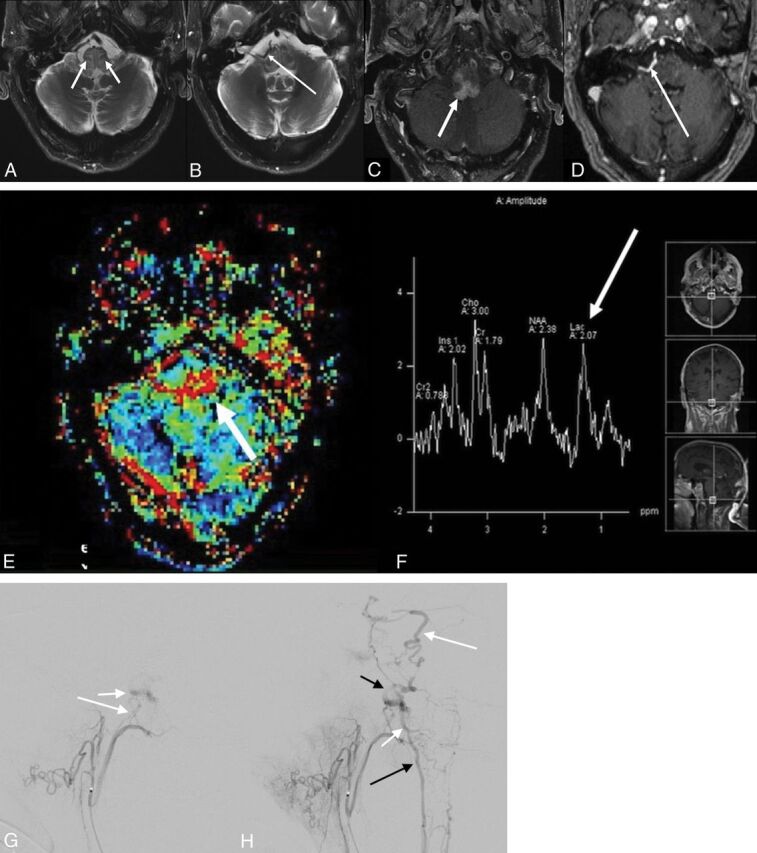

A 72-year-old man presented with 3 months of imbalance, slurred speech, and dysphagia. He had a vestibular schwannoma resected 15 years prior. MR imaging demonstrated relatively diffuse T2 hyperintense signal within the medulla, with peripheral and internal linear regions of sparing, with intense enhancement in the medulla and adjacent cerebellar flocculus (Fig 2A–D). Additionally, an unusual enhancing vascular structure, near but separate from the right vertebral artery, was identified (Fig 2D). Concern was initially raised for a DAVF. The patient underwent 4-vessel cerebral angiography outside our department, but no vascular malformation was identified. Subsequent clinical work-up, including multiple lumbar punctures for cytology, failed to demonstrate evidence of malignancy. MR spectroscopy/perfusion revealed a lactate/lipid peak and prolongation of the mean transit time and mildly decreased cerebral blood volume within the medulla (Fig 2E, -F). The case was reviewed by the tumor board, and one of the authors strongly suggested a DAVF, despite the prior negative findings on angiography (which did not include selective injections of the external carotid arteries). Repeat cerebral angiography in our department with selective external carotid and, potentially, spinal artery injections, was recommended. Arteriovenous shunting in the region of the anterior condylar vein was identified on repeat angiography (Fig 2G). Dilated draining veins along the brain stem and upper cord were present (Fig 2H). Embolization was performed with Onyx injection (Covidien, Irvine, California) in the neuromeningeal division of the ascending pharyngeal artery feeding the fistula. No evidence of residual DAVF was seen, and the patient had improvement in symptoms, particularly his dysphagia. Five-month follow-up angiography did not show recurrence, and follow-up MR imaging revealed resolution of edema and enhancement.

Fig 2.

A 72-year-old man with 2- to 3-month history of imbalance and dysphagia. A and B, Axial T2WI with fat suppression from initial MR imaging demonstrates diffuse hyperintense signal in the medulla with segments of linear sparing (short white arrows), creating a geographic pattern, as well as an unusual vascular structure (long white arrow). C and D, Axial postcontrast T1-weighted fat-suppression imaging demonstrates intense enhancement within the medulla (short white arrow) and again depicts the unusual vascular structure (long white arrow), which appears separate from the vertebral arteries. Dynamic susceptibility contrast MR perfusion imaging reveals prolongation in mean transit time (short white arrow, E), and MR spectroscopy with a TE of 35 ms (F) reveals a lactate/lipid peak (long white arrow) without significant elevation in choline. G, Lateral view from a selective right ascending pharyngeal injection on DSA demonstrates arteriovenous shunting with early opacification of the anterior condylar vein (short white arrow) supplied by feeders from the neuromeningeal division of the ascending pharyngeal artery (long white arrow). H, More delayed lateral image demonstrates dilated veins along the surface of the brain stem and upper cord (short white arrow), draining both superiorly along the anterolateral surface of the pons toward the petrosal vein (long white arrow) and inferiorly toward the anterior spinal vein (long black arrow). The tortuous vein (short black arrow) likely corresponds to the anomalous venous structure seen on the original MR imaging.

Case 3.

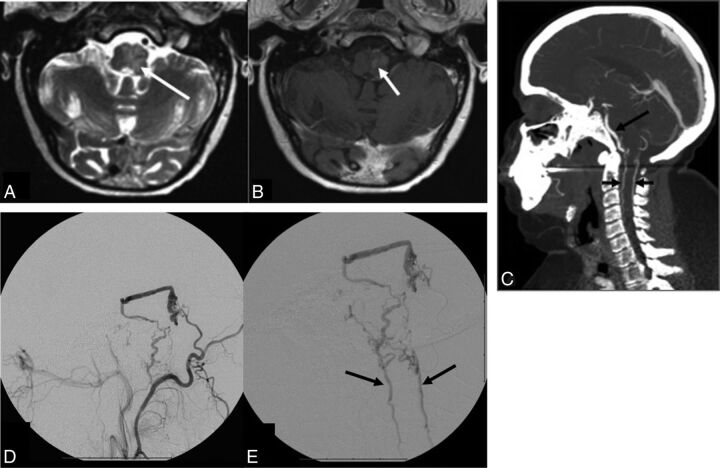

A 35-year-old woman with a medical history significant for pilocytic astrocytoma as a child presented with 4 weeks of progressive unsteady gait and lower extremity weakness as well as dysphonia and nasal speech. MR imaging demonstrated patchy T2 hyperintensity within the medulla, with peripheral and several internal linear regions of sparing, and subtle intramedullary enhancement (Fig 3A, -B). Serpiginous vessels on postcontrast sequences and flow voids were seen along the surface of the medulla and brain stem. CTA revealed prominent perimedullary and ventral and dorsal spinal veins (Fig 3C). Cerebral angiography demonstrated a DAVF in the wall of the superior petrosal sinus (Fig 3D, -E). Endovascular embolization was performed with injection of Onyx into the mastoid branch of the occipital artery. The patient experienced marked clinical improvement with mild residual left lower extremity weakness. A 3-month follow-up angiogram showed no recurrence.

Fig 3.

A 35-year-old woman with a history of pilocytic astrocytoma as a child now presenting with 4 weeks of progressive difficulty in walking. A, Axial T2WI reveals patchy hyperintensity within the medulla (long white arrow) with peripheral sparing. B, Axial postcontrast T1WI demonstrates subtle intramedullary enhancement (short white arrow). C, Sagittal CTA reformatted image depicts prominent perimedullary (long black arrow) as well as ventral and dorsal spinal veins (short black arrows). Selective DSA of the occipital (D) and mastoid branch via microcatheter (E) demonstrates the fistulous connection in the wall of the superior petrosal sinus with retrograde pial reflux via the petrosal vein to the perimedullary and spinal veins (black arrows).

Case 4.

A 64-year-old woman presented to an outside hospital with progressive bilateral arm and leg weakness for the prior 6 months that gradually evolved to tetraparesis. MR imaging of the cervical spine revealed diffuse T2 hyperintensity within the medulla and cervical spinal cord, with peripheral and internal linear regions of sparing, with relatively diffuse enhancement. This was initially diagnosed as transverse myelitis and managed with steroids, intravenous immunoglobulin, and plasma exchange. The patient's symptoms progressed for the next 5 months, and she was seen at our institution. MR imaging revealed mild expansion of the medulla and cervical spinal cord with a similar pattern of T2 hyperintensity and enhancement. Subtle prominent vessels were now evident along the ventral pial surface of the medulla. CTA revealed venous congestion at the cervicomedullary junction, and cerebral angiography demonstrated a DAVF along the superior petrosal sinus supplied by the tentorial branch of the inferolateral trunk with perimedullary venous drainage. The DAVF was initially treated with an Onyx injection into the occipital arterial supply; however, residual shunting was seen without successful penetration of Onyx on the venous side. Surgical resection was performed the following day, and 1-week angiographic follow-up demonstrated no residual fistula. Clinical recovery, however, was limited, with persistent tetraparesis 12 months after treatment.

Case 5.

A 50-year-old man presented with new-onset upper and lower extremity weakness. He was initially diagnosed with transverse myelitis and came to our institution for a second opinion. MR imaging of the cervical spine revealed expansion of the lower medulla and cervical cord with T2 hyperintensity, sparing the periphery, and faint enhancement with prominent vessels along the ventral cervical cord. Cerebral angiography revealed a spinal DAVF in the left C1 foramen with perimedullary venous drainage to the anterior spinal vein. Due to the short arterial pedicle, endovascular management was deferred. Surgical management was initially unsuccessful with persistence of the DAVF. His symptoms progressed for the next 6 weeks to marked lower extremity weakness, bowel and bladder dysfunction, and dysphagia, with an inability to maintain secretions, requiring percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube placement and tracheostomy. A second operation was then performed and was successful; however, clinical examination findings remained unchanged.

Discussion

While an intracranial DAVF with perimedullary spinal venous drainage is rare, even more uncommon is its presentation with medullary or pontomedullary edema, with only 31 cases previously reported in the English language medical literature. Because timely diagnosis is paramount in minimizing the potential for catastrophic outcomes, it is critical to make the referring physician and neuroradiologist more cognizant of this rare-yet-characteristic imaging manifestation of a DAVF.

This series illustrates the challenges in diagnosing this atypical presentation of DAVF. Because symptomatology is related to the distribution of venous drainage rather than the site of the fistula, the clinical presentation may mimic demyelinating and inflammatory disorders, brain stem and spinal cord infarction, or neoplasms. Symptom onset may be sudden or gradual, with our patients' presentations ranging from sudden onset of nausea and vomiting to gradually progressive tetraparesis.8–12 As exemplified in our patients, the challenges in recognizing this rare disease entity often lead to a significant delay in diagnosis, on the order of several months from the time of initial investigation and months to years from the time of initial symptoms.

Imaging findings of DAVF often overlap more common disease entities, convoluting the diagnostic dilemma. Prominent perimedullary flow voids on T2WI, a feature suggestive of an underlying vascular malformation, are present in only 37% of cases.4 With contrast-enhanced imaging, the detection rate of atypical perimedullary vessels increases to 76% but is often subtle.5 Use of MRA increases the detection rate to 85%.5 Four of our 5 patients (80%) retrospectively demonstrated atypical perimedullary vessels or flow voids on initial MR imaging, subtle in some instances. Prominent veins are likely a later sign.5 In Cognard type V lesions, the perimedullary venous drainage is predominantly through the anterior spinal veins, making them less prominent on MR imaging.4

Central medullary or pontomedullary edema has been reported in 73% of patients with Cognard type V DAVFs.5 All our patients demonstrated a nearly identical pattern of geographic central medullary edema with sparing of the periphery as well as internal linear segments in a tigroid pattern. In this series, not all cases of Cognard type V DAVFs were reviewed; rather, only those cases demonstrating central medullary edema were included, so the proportion of total cases of type V DAVFs from our institutions with the aforementioned specific imaging features is unknown. This peripheral sparing appearance has been mentioned in case reports.13 This pattern contrasts with the infiltrative process seen in brain stem tumors. Maintenance of the normal signal of the peripheral subpial tissue may be secondary to direct drainage of the extracellular vasogenic edema into the CSF through the permeable pia mater.14,15 Perivascular spaces may also play a role in draining the peripheral tissue.16

Of the 20 cases in the literature reporting on the presence of medullary contrast enhancement for Cognard type V DAVFs, 11 cases (55%) demonstrated enhancement. Medullary enhancement was demonstrated in all our cases, 4 of which were initially scanned on a 1.5T scanner and 1 on a 3T scanner, with 3 different vendors used. Medullary enhancement was demonstrated in all our cases. The combination of medullary edema and enhancement may lead to the consideration of neoplastic or inflammatory etiologies, as was the case in 3 of our 5 cases, and has reportedly led to inappropriate brain stem biopsies.5 Two of our patients underwent MR perfusion/spectroscopy because a neoplasm was considered. MR perfusion and spectroscopy in DAVF are also uncommonly reported. A prolonged mean transit time with decreased cerebral blood volume may be present secondary to venous congestion with ischemia, seen in both of our patients.17,18 Additionally, spectroscopy may reveal increased lactate, which was demonstrated in 1 of our patients.

Four of our 5 patients had true intracranial DAVFs. Case 5 revealed the site of the fistula at the craniocervical junction along the C1 foramen. In 3 of our 4 cases of true intracranial DAVFs, conventional angiography revealed the site of the fistula to be along the superior petrosal sinus, and in 1 case, the anterior condylar vein. The goal of treatment is closure of the draining vein proximally as it exits the fistula. Successful endovascular embolization with Onyx was performed in 2 of our patients; combined embolization and an operation, in 2 patients; and 2 operations, in 1 patient. As in case 2, the medullary edema might resolve following treatment.5

Bulbar symptoms were present in 3 of our 5 (60%) cases: case 2 (slurred speech and dysphagia), case 3 (dysphonia and nasal speech), and case 5 (inability to maintain secretions). A systematic review of the literature on Cognard type V DAVFs identified bulbar symptoms in 31% of patients and found no significant difference in prognosis between those with versus those without bulbar symptoms.19 In our series, 2 of 3 patients with clinical improvement and 1 of 2 patients without clinical improvement had bulbar symptoms, further exemplifying a lack of relationship between the presence of bulbar symptoms and prognosis.

Three of our 5 patients (60%) had near-complete resolution of symptoms and angiographically complete occlusion of the DAVF. Unfortunately, the 2 patients with the most significant delay in diagnosis and treatment did not show significant clinical improvement following treatment, further exemplifying the importance of early diagnosis and management.

Conclusions

This relatively unusual-but-characteristic pattern of medullary edema with areas of sparing and patchy enhancement should prompt scrutiny for atypical perimedullary vessels. If no such vessels are identified, MRA/CTA or conventional angiography should be recommended. Of utmost importance, selective injection of the external carotid arteries is mandated at the time of conventional angiography to avoid false-negative results as was the case in 1 of our patients.

ABBREVIATION:

- DAVF

dural arteriovenous fistula

Footnotes

Disclosures: Richard Silbergleit—UNRELATED: Consultancy: Relievant Medsystems.

Several of these cases were previously presented at: Annual Meeting of the American Society of Neuroradiology and the Foundation of the ASNR Symposium, May 21-26, 2016; Washington, DC.

References

- 1. Kwon BJ, Han MH, Kang HS, et al. . MR imaging findings of intracranial dural arteriovenous fistulas: relations with venous drainage patterns. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2005;26:2500–07 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cognard C, Gobin YP, Pierot L, et al. . Cerebral dural arteriovenous fistulas: clinical and angiographic correlation with a revised classification of venous drainage. Radiology 1995;194:671–80 10.1148/radiology.194.3.7862961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. van Rooij WJ, Sluzewski M, Beute GN. Intracranial dural fistulas with exclusive perimedullary drainage: the need for complete cerebral angiography for diagnosis and treatment planning. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2007;28:348–51 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Haryu S, Endo T, Sato K, et al. . Cognard type V intracranial dural arteriovenous shunt: case reports and literature review with special consideration of the pattern of spinal venous drainage. Neurosurgery 2014;74:E135–42; discussion E142 10.1227/NEU.0000000000000069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Roelz R, Van Velthoven V, Reinacher P, et al. . Unilateral contrast-enhancing pontomedullary lesion due to an intracranial dural arteriovenous fistula with perimedullary spinal venous drainage: the exception that proves the rule. J Neurosurg 2015;123:1534–39 10.3171/2014.11.JNS142278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ricolfi F, Manelfe C, Meder JF, et al. . Intracranial dural arteriovenous fistulae with perimedullary venous drainage: anatomical, clinical and therapeutic considerations. Neuroradiology 1999;41:803–12 10.1007/s002340050846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Brunereau L, Gobin YP, Meder JF, et al. . Intracranial dural arteriovenous fistulas with spinal venous drainage: relation between clinical presentation and angiographic findings. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1996;17:1549–54 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gaensler EH, Jackson DE Jr, Halbach VV. Arteriovenous fistulas of the cervicomedullary junction as a cause of myelopathy: radiographic findings in two cases. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1990;11:518–21 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hähnel S, Jansen O, Geletneky K. MR appearance of an intracranial dural arteriovenous fistula leading to cervical myelopathy. Neurology 1998;51:1131–35 10.1212/WNL.51.4.1131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Li J, Ezura M, Takahashi A, et al. . Intracranial dural arteriovenous fistula with venous reflux to the brainstem and spinal cord mimicking brainstem infarction: case report. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 2004;44:24–28 10.2176/nmc.44.24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cahan LD, Higashida RT, Halbach VV, et al. . Variants of radiculomeningeal vascular malformations of the spine. J Neurosurg 1987;66:333–37 10.3171/jns.1987.66.3.0333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hassler W, Thron A. Flow velocity and pressure measurements in spinal dural arteriovenous fistulas. Neurosurg Rev 1994;17:29–36 10.1007/BF00309983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hurst RW, Grossman RI. Peripheral spinal cord hypointensity on T2-weighted MR images: a reliable imaging sign of venous hypertensive myelopathy. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2000;21:781–86 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Nicholas DS, Weller RO. The fine anatomy of the human spinal meninges: a light and scanning electron microscopy study. J Neurosurg 1988;69:276–82 10.3171/jns.1988.69.2.0276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hutchings M, Weller RO. Anatomical relationships of the pia mater to cerebral blood vessels in man. J Neurosurg 1986;65:316–25 10.3171/jns.1986.65.3.0316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fleury J, Gherardi R, Poirier J. Pathology of perivascular spaces in the central nervous system [in French]. Ann Pathol 1984;4:249–57 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Doege CA, Tavakolian R, Kerskens CM, et al. . Perfusion and diffusion magnetic resonance imaging in human cerebral venous thrombosis. J Neurol 2001;248:564–71 10.1007/s004150170133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kim DJ, Krings T. Whole-brain perfusion CT patterns of brain arteriovenous malformations: a pilot study in 18 patients. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2011;32:2061–66 10.3174/ajnr.A2659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. El Asri AC, El Mostarchid B, Akhaddar A, et al. . Factors influencing the prognosis in intracranial dural arteriovenous fistulas with perimedullary drainage. World Neurosurg 2013;79:182–91 10.1016/j.wneu.2012.09.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]