Abstract

BACKGROUND AND PURPOSE:

The Seikaly and Jha submandibular gland transfer surgery is performed to facilitate gland shielding during radiation therapy for head and neck tumors to circumvent radiation-induced xerostomia. It results in an asymmetric postsurgical appearance of the submandibular and submental spaces. Our purpose was to characterize the morphologic and enhancement characteristics of the transferred submandibular gland and identify potential pitfalls in postoperative radiologic interpretation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS:

This retrospective study identified patients with head and neck cancer who had undergone the submandibular gland transfer procedure at our institution. Chart reviews were performed to identify relevant oncologic histories and therapies. CT and MR neck imaging was reviewed to characterize morphologic and enhancement characteristics of the pre- and postoperative submandibular glands, as well as interpretive accuracy.

RESULTS:

Eleven patients with oropharyngeal and nasopharyngeal squamous cell carcinomas who underwent submandibular gland transfer were identified. The transferred glands were significantly lengthened in the anteroposterior dimension compared with contralateral glands (P < .001) and displaced anteriorly and inferiorly within the submandibular and submental spaces. Enhancement patterns of the transferred submandibular glands varied, depending on the time of imaging relative to the operation and radiation therapy. Submandibular gland transfer was acknowledged in the postoperative report in 7/11 cases. Errors in interpretation were present in 2/11 reports.

CONCLUSIONS:

After the submandibular gland transfer procedure, the submandibular and submental spaces lose their symmetric appearances as the transferred submandibular glands become lengthened and located more anteriorly and inferiorly, with variable enhancement characteristics. Familiarity with the postsurgical appearance of the transferred submandibular glands is key to accurate imaging interpretation.

The Seikaly and Jha submandibular transfer procedure consists of the surgical relocation of the submandibular gland (SMG) to the ipsilateral submental space. The aim of this surgery is to displace the submandibular gland farther away from the highest dose regions of radiation, thereby decreasing the risk of radiation-induced xerostomia.1–6 Briefly, the procedure begins with a limited level I neck dissection and release of the submandibular gland from its surrounding tissues. As originally described, this is followed by evaluation for retrograde flow in the facial artery and vein supplying the gland and ligation of these vessels if there is sufficient retrograde flow. Alternatively, the gland and supporting vessels can be mobilized sufficiently to allow stretching of the vessels as the gland is repositioned anteriorly. The mylohyoid muscle is then bisected to allow repositioning of the submandibular gland into the submental space, while maintaining its connection with the submandibular duct and ganglion (Fig 1). Once in the submental space, the SMG is anchored deep or sutured superficial to the ipsilateral anterior belly of the digastric muscle.3,7

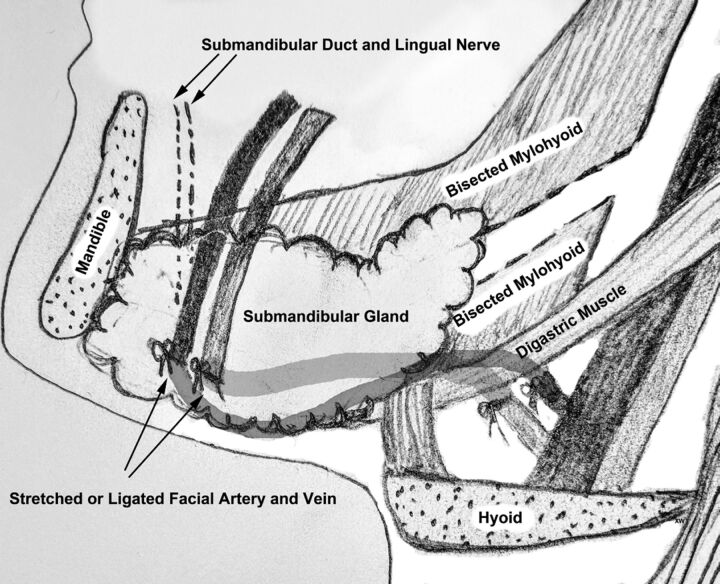

Fig 1.

Illustrative schematic demonstrating the key steps in the SMG transfer operation, including mobilization or ligation of the facial artery and vein proximal to the SMG, anterior and inferior translation of the gland into the submental space, and bisection of the mylohyoid muscle to allow repositioning of the submandibular duct and ganglion.3,7

Because this procedure is only performed contralateral to the primary head and neck malignancy, it results in an asymmetric postsurgical appearance of the submandibular and submental spaces, which can lead to diagnostic errors. The confounding postoperative appearance of this transferred submandibular gland has been previously demonstrated on PET/CT imaging.8 The purpose of this study was to better characterize the CT and MR imaging findings of the transferred SMG and to identify potential pitfalls in the evaluation of the postsurgical submandibular and submental spaces.

Materials and Methods

This institutional review board–approved, Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act–compliant study reviewed surgical records from University of California, San Francisco, from the past 5 years to identify patients with head and neck cancer who had undergone the submandibular gland transfer procedure. A medical chart review was conducted to identify the patient's primary site of disease and pathology, date of the surgical intervention, description of the surgical intervention (as per the operative report), and dates and dosages of subsequent radiation treatment. Average radiation doses with SDs to the transferred and contralateral SMGs were calculated. Student t tests were performed to assess whether the transferred SMGs received significantly lower radiation doses relative to the contralateral glands.

The available pre- and postoperative neck CT and MR imaging examinations of these patients were then reviewed to characterize morphologic and enhancement characteristics of the SMGs and key surrounding structures, including the mylohyoid, anterior belly of the digastric, and platysma muscles. Specific morphologic measurements of the submandibular glands were obtained as described in Table 1. Paired pre and post t tests were performed to determine whether there was any statistically significant difference in positions between the transferred SMGs and the contralateral glands before and after surgery. Radiology reports were also reviewed for any commentary on the SMGs.

Table 1:

SMG morphologic measurement definitions

| Morphologic Measurement | Definition | Direction of Measurement |

|---|---|---|

| AP length | As measured between anteriormost border of gland and posteriormost border of SMG | On axial images, perpendicular to axis connecting the mandibular condyles |

| AP length difference | Difference between the AP lengths of the SMGs by subtraction of the AP length of the contralateral gland from the transferred gland | On axial images, perpendicular to axis connecting the mandibular condyles |

| Posterior margin difference | Distance between the posteriormost border of the gland and that of the contralateral gland | On axial images, perpendicular to axis formed by connecting the mandibular condyles |

| Superior margin difference | Distance between the superiormost border of the gland and that of the contralateral gland | On coronal images, perpendicular to axis formed by connecting the mandibular condyles |

| Anteroinferior margin difference | Distance between the anteroinferior-most border of the gland and that of the contralateral gland | On axial images, perpendicular to axis formed by connecting the mandibular condyles |

Note:—AP indicates anteroposterior.

Results

Patient Characteristics

Eleven patients with head and neck malignancies (10 men and 1 woman; ages, 44–64 years) underwent the submandibular transfer procedure at our institution and underwent postoperative contrast-enhanced CT or MR imaging. Eight procedures were performed by 1 surgeon, and 3 were performed by 2 other surgeons. All primary tumors had a histology of squamous cell carcinoma, and the primary subsites were nasopharyngeal in 1 patient and oropharyngeal in 10 patients, with tonsillar primary disease in 7 patients and base of the tongue primary disease in 3 patients. All patients had preoperative neck CT, though 2 patients had only noncontrast CT studies. Two patients also had preoperative MR imaging. Postoperatively, 9 patients underwent contrast-enhanced MR imaging, and 6 patients underwent contrast-enhanced CT. Ten of 11 patients underwent radiation-planning NCCT after the operation.

All patients were treated with chemoradiation with curative intent, and none had preradiation resection of the primary tumor or involved lymph nodes. Two patients underwent radiation treatment at outside institutions; therefore, dosage information was not available for these cases. Dosage information for the remaining patients demonstrated lower dosages to the transferred glands, which received on average 35.90 ± 13.88 Gy, than to the contralateral glands, which received on average 63.85 ± 4.89 Gy (Table 2, P < .001).

Table 2:

Radiation therapy detailsa

| Patient No. | Primary Tumor Site | Prescribed Dose to Primary Tumor (Gy) | Prescribed Dose to Involved Neck (Gy) | Mean Dose to SMG on Involved Side (Gy) | Prescribed Dose to Uninvolved Neck (Gy) | Mean Dose to Transferred SMG (Gy) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | R BOT | 60 | 54 | 58.64 | 48 | 20.45 |

| 2 | R tonsil | 69.96 | 59.4 | 61.33 | 54.12 | 28.99 |

| 3 | R tonsil | 69.96 | 59.4 | 68.8 | 54.12 | 43.97 |

| 4 | R BOT | 69.96 | 59.4 | 66.01 | 59.4 | 41.44 |

| 5 | R BOT | 60 | 54 | 60.01 | 48 | 44.95 |

| 6 | L tonsil | 66 | 59.4 | 66.7 | 54.12 | 16.59 |

| 7 | R tonsil | 66 | 59.4 | 59.4 | 54.12 | 38.8 |

| 8 | R tonsil | 69.96 | 59.4 | 72.7 | 54.12 | 27.17 |

| 9 | Nasopharynx | 69.96 | 59.4 | 61.02 | 59.4 | 60.77 |

| Average dose (Gy) | 66.87 | 58.20 | 63.85 | 53.93 | 35.90 | |

| SD | 4.24 | 2.38 | 4.89 | 4.04 | 13.88 |

Note:—R indicates right; BOT, base of tongue; L, left.

Postsurgical radiation dosages for the 9 out of 11 patients who received radiation therapy at our institution following the SMG transfer procedure. Per the Student t test, the transferred SMG received a significantly lower radiation dose than the contralateral SMG (P < .001).

SMG Morphology

Preoperatively, there was no significant difference in location or morphology between the bilateral submandibular glands in each patient (Table 3). Specifically, there were no significant differences between the preoperative anteroposterior length differences, anteroposterior locations of the anteroinferior margin of the SMGs, and the posterior and superior margins of the gland to be transferred relative to the contralateral side (all P values > .05).

Table 3:

SMG locationa

| Preoperative (mm) | P Value | Postoperative (mm) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anteroposterior length difference | 2.5 (−4–5) | .28 | 10.5 (−1–17) | <.001 |

| Anteroinferior margin difference | 0 (0–0) | 13.5 (10–16) | <.001 | |

| Posterior margin difference | −1.8 (−9–3) | .10 | 7.2 (0–16) | <.001 |

| Superior margin difference | 0.2 (−3–6) | .79 | −7.5 (−15–0) | <.001 |

Preoperative and postoperative morphologic features of the transferred SMGs, presented as averaged length and location differences between the SMGs in each patient (transferred gland–contralateral gland) followed by ranges of the differences. Positive values indicate anterior and superior directions, respectively. P values for significance of length differences are derived from paired pre- and post-t tests with a reference value of 0 mm (no difference).

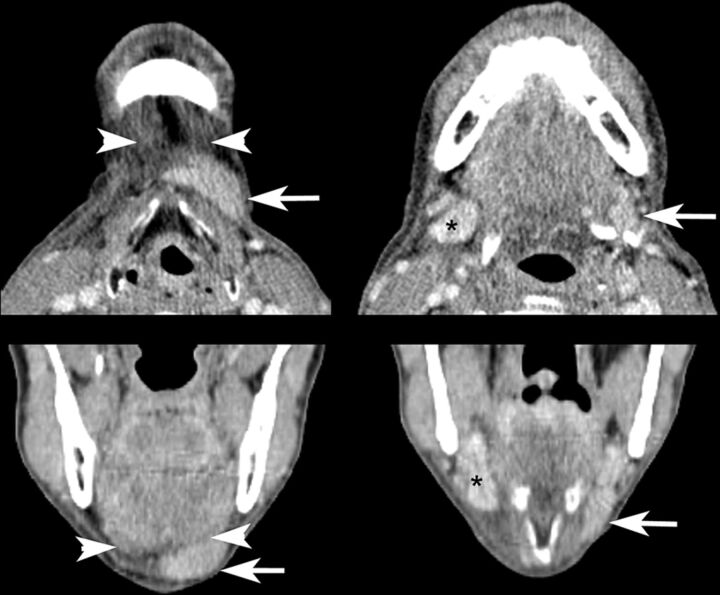

On postoperative imaging, the transferred SMGs were lengthened significantly in the anteroposterior dimension compared with the contralateral glands (Table 3). The transferred SMGs were located more anteriorly within the submandibular and submental spaces, as characterized by the more anterior locations of their anteroinferior and posterior margins (Fig 2). On average, the superior margins of the transferred glands were located inferiorly relative to the contralateral glands.

Fig 2.

Contrast-enhanced CT images demonstrating the typical asymmetric appearance of the submental and submandibular spaces after SMG transfer. The left transferred SMG (arrows) is elongated and displaced inferiorly and anteriorly into the submental space superficial to the anterior belly of the digastric muscle (arrowheads), resulting in an asymmetric soft-tissue density in the submental space and diminished soft-tissue volume in the submandibular space relative to the contralateral gland (asterisks). Note also edema of surrounding tissues in this patient who was 3 months postchemoradiation with cisplatin and NRG-HN002 (NCT02254278; ClinicalTrials.gov) de-escalation protocol at time of imaging.

In 10 of the 11 cases, the submandibular gland was in the subcutaneous tissue superficial to the anterior belly of the digastric muscle; however, in 1 case, it was implanted deep to the ipsilateral anterior belly of the digastric muscle (Fig 3).

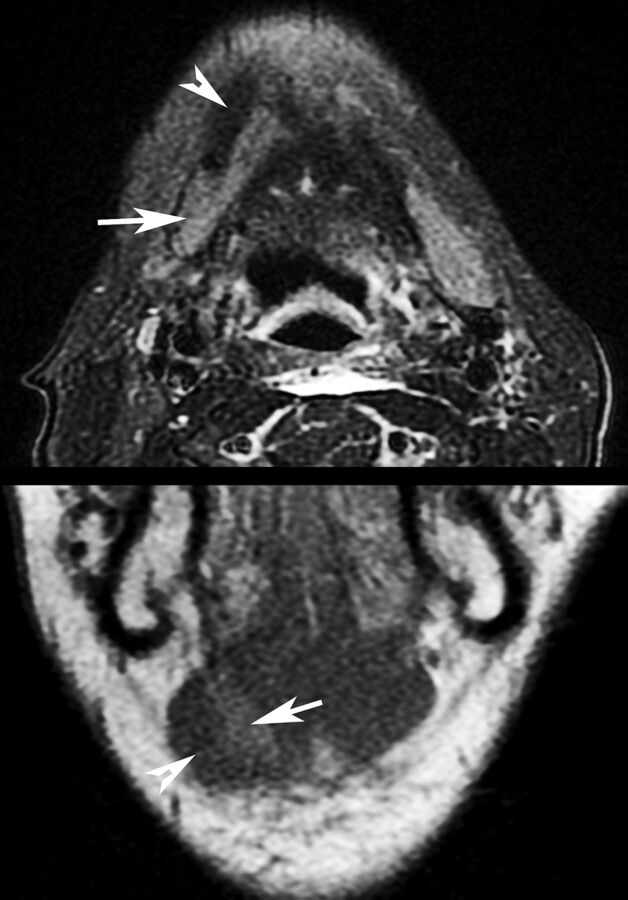

Fig 3.

Appearance of SMG (arrows) transferred deep to the anterior belly of the digastric muscle (arrowheads) on axial T2-weighted, fat-suppressed imaging and coronal T1-weighted imaging. The patient was 2 months postchemoradiation with cisplatin and intensity-modulated radiation therapy at imaging.

SMG CT and MR Imaging Enhancement

On preoperative contrast-enhanced CT, the percentage Hounsfield differences between the target gland and the contralateral gland varied between −18% and 9%, though for all cases except 1, the percentage differences fell below 10%. In 1 exceptional case, there was a percentage difference of −18% between the operative target SMG and the contralateral gland. This patient had bulky enhancing lymph nodes and soft-tissue stranding adjacent to the contralateral gland, suggesting concomitant inflammation or infection.

For the 6 cases that had postoperative contrast-enhanced CT, the transferred gland demonstrated comparable, to slightly decreased enhancement relative to the contralateral gland, ranging from −35% to 9% difference in Hounsfield units.

On postoperative MR imaging, most of the transferred SMGs demonstrated decreased enhancement compared with the contralateral glands (range, −14 to −1%). The 2 postoperative MRIs that demonstrated increased enhancement (18% and 35% differences) were acquired in the short term, 24 and 28 days postoperatively and before any radiation therapy. Other MRIs were acquired between 52 and 322 days, after the patients had started or undergone radiation therapy.

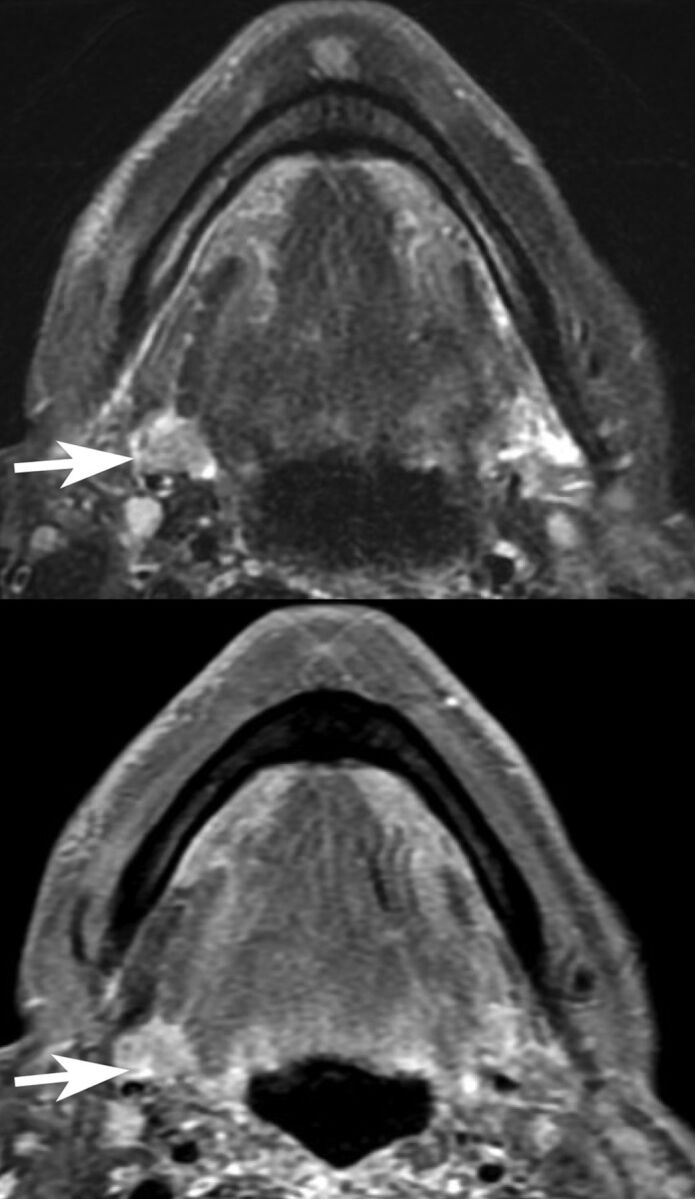

Additional MR Imaging Findings

For MR imaging examinations performed between 24 and 106 days postoperatively, T2 hyperintense edema was seen in the platysma musculature adjacent to the transferred submandibular gland (5 of 9 cases, Fig 4). For the 4 cases in which MR imaging was performed between 138 and 322 days postoperatively, no edema was evident. Although enhancement and T2 hyperintense signal were noted in the mylohyoid and digastric musculature for some cases, no correlation was noted between the imaging date and the presence or absence of these findings.

Fig 4.

Axial and coronal fat-suppressed postcontrast T1-weighted imaging performed 28 days postoperatively for staging purposes demonstrated platysma enhancement (arrows) adjacent to the transferred SMG. The patient had not yet undergone chemoradiation at imaging.

Imaging Report Review

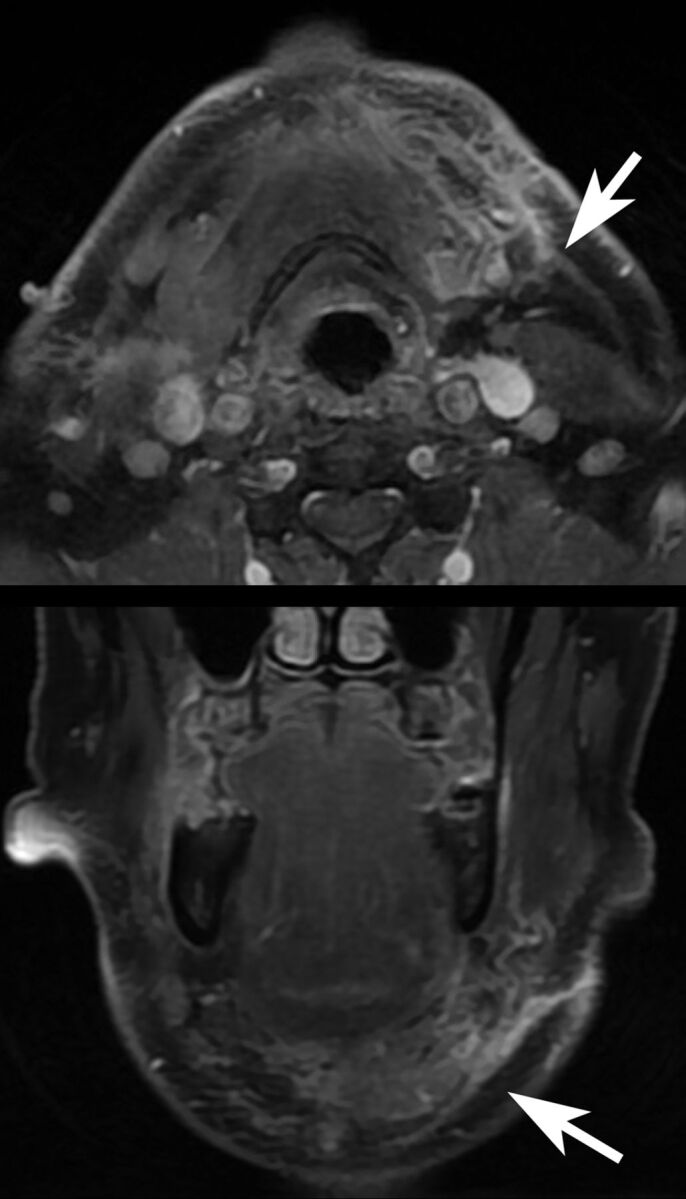

For 7 of the 11 cases, the history of submandibular transfer was either provided as a part of the clinical history or acknowledged in the body of the report and presumably had either been recognized or gleaned from the electronic medical record by the radiologist. In one of the cases, the clinical history of submandibular transfer was provided, but the report incorrectly noted that the transferred gland “was not visualized.” In 1 of the cases in which the history of submandibular gland transfer was neither provided nor acknowledged, the superior aspect of the contralateral SMG was incorrectly interpreted as a parapharyngeal mass (Fig 5).

Fig 5.

Postoperative asymmetry within the submandibular space results in misinterpretation of the superior aspect of the normal contralateral SMG (arrows) as a parapharyngeal mass (axial T2 fat-suppressed and postcontrast imaging). The patient was 2 months postchemoradiation with cisplatin and intensity-modulated radiation therapy at imaging.

Discussion

Our findings demonstrate that while preoperative morphologies, locations, and enhancement characteristics of the SMGs are symmetric, the SMG becomes elongated and translated anteriorly and inferiorly into the submental space after the SMG transfer procedure and may demonstrate differential enhancement patterns. This scenario results in considerable asymmetry in the submandibular and submental spaces, which causes challenges in image interpretation.

SMG ptosis is an age-related phenomenon in which inferior displacement of both submandibular glands results from laxity of the platysma muscle and skin and can be a concern in cosmetic neck rejuvenation.9 Ptotic SMGs are symmetrically inferiorly displaced within the submandibular space and are not translated anteriorly into the submental space as is the case with a unilaterally transferred SMG.9 The asymmetric appearance of a transferred SMG and the history of a prior operation distinguish it from ptotic SMGs.

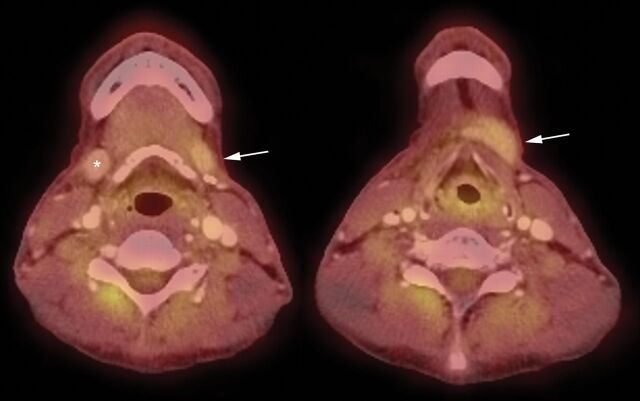

Enhancement of the transferred SMG relative to the contralateral SMG appears to depend on the timing of the study. Increased MR imaging enhancement in the transferred SMG in the immediate postoperative period (24 and 28 days) may reflect reactive hyperemia and correlate with the considerably increased FDG avidity in the transferred gland reported 3 weeks postoperatively in the literature.8 For all MR imaging examinations performed >52 days from the time of the operation, the transferred SMG demonstrated decreased enhancement relative to the contralateral gland. This may reflect a sequela of altered vascularity, because ligation of the facial artery and vein proximal to the SMG and reliance on retrograde collaterals are components of the transfer procedure.1 Another cause for differential enhancement may be the different radiation dosages delivered to the SMGs. Increased enhancement of irradiated salivary glands has been well described previously, especially at dosages of >45 Gy.10,11 The fact that the transferred SMGs received, on average, 35.90 ± 13.88 Gy as opposed to the contralateral glands, which received, on average, 63.85 ± 4.89 Gy, may contribute to these differential enhancement characteristics, especially given that 39 Gy is commonly thought to be a “submandibular gland–sparing” dose due to dose tolerance considerations.12 Relatively preserved gland function may also explain the mildly increased FDG uptake of the transferred, less irradiated gland compared with the contralateral gland reported in a patient 2 years postoperatively8 and replicated in a patient in our cohort in a PET/CT examination acquired 5 months after the operation (Fig 6).

Fig 6.

PET/CT images demonstrating mildly increased FDG uptake in the left transferred SMG (arrows) compared with the contralateral gland (asterisk) 5 months after SMG transfer surgery and 3 months following conclusion of chemoradiation. These findings are congruent with previously published PET findings in a SMG transfer operation and may reflect relatively preserved function in the transferred gland.8

Edema of the platysma musculature appears to resolve with increased time after the operation, suggesting that this is a postoperative finding. The lack of correlation between imaging date and the presence or absence of mylohyoid/digastric muscle enhancement and T2 hyperintensity suggest that these findings may reflect denervation changes.

Regardless of whether the clinical history of SMG transfer is provided, the presence of asymmetric soft tissue within the submandibular and submental spaces can be confusing. Lack of familiarity with the appearance and submental location of the transferred gland may account for the case in which the history of SMG transfer was recognized but the transferred gland was reported as not visualized. Asymmetry of the submandibular spaces may have contributed to the incorrect interpretation of the superior aspect of a contralateral SMG as a parapharyngeal mass because the transferred gland was no longer in its expected location to provide a point of reference.

Conclusions

Familiarity with the postsurgical appearance of SMG transfer and recognizing the location of the transferred gland and its relationship to the contralateral SMG is important to correctly interpret subsequent neck imaging. Our study demonstrates that after this procedure, there is a loss of SMG symmetric morphology. The transferred gland is located more anteriorly and inferiorly within the submandibular and submental spaces, most frequently superficial to the anterior belly of the digastric musculature. In all except the most immediately postoperative MR imaging examinations (<52 days), the transferred submandibular gland appears to demonstrate less intense enhancement than the native contralateral gland, though T2 signal hyperintensity within the platysma muscle was reliably seen in examinations performed in the first 106 days.

ABBREVIATION:

- SMG

submandibular gland

Footnotes

Disclosures: Sue S. Yom—UNRELATED: Consultancy: BioMimetix Pharmaceutical, Eli Lilly; Grants/Grants Pending: Merck, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Genentech*; Royalties: UpToDate, Springer; Travel/Accommodations/Meeting Expenses Unrelated to Activities Listed: AstraZeneca. Chase M. Heaton—UNRELATED: Consultancy: OncoSec. Christine M. Glastonbury—UNRELATED: Royalties: Elsevier-Amirsys, Comments: book and chapter royalties. *Money paid to the institution.

Paper previously presented at: Annual Meeting of the American Society of Head and Neck Radiology, September 16–20, 2017; Las Vegas, Nevada.

REFERENCES

- 1. Jha N, Seikaly H, McGaw T, et al. Submandibular salivary gland transfer prevents radiation-induced xerostomia. Int J Radiat Oncol Boil Phys 2000;46:7–11 10.1016/S0360-3016(99)00460-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Liu R, Seikaly H, Jha N. Anatomic study of submandibular gland transfer in an attempt to prevent postradiation xerostomia. J Otolaryngol 2002;31:76–79 10.2310/7070.2002.19035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Seikaly H, Jha N, Harris JR, et al. Long-term outcomes of submandibular gland transfer for prevention of postradiation xerostomia. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2004;130:956–61 10.1001/archotol.130.8.956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rieger J, Seikaly H, Jha N, et al. Submandibular gland transfer for prevention of xerostomia after radiation therapy: swallowing outcomes. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2005;131:140–45 10.1001/archotol.131.2.140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Jha N, Seikaly H, Harris J, et al. Phase III randomized study: oral pilocarpine versus submandibular salivary gland transfer protocol for the management of radiation-induced xerostomia. Head Neck 2009;31:234–43 10.1002/hed.20961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jha N, Harris J, Seikaly H, et al. A phase II study of submandibular gland transfer prior to radiation for prevention of radiation-induced xerostomia in head-and-neck cancer (RTOG 0244). Int J Radiat Oncol Boil Phys 2012;84:437–42 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2012.02.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Seikaly H, Jha N, McGaw T, et al. Submandibular gland transfer: a new method of preventing radiation-induced xerostomia. Laryngoscope 2001;111:347–52 10.1097/00005537-200102000-00028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Makis W, Ciarallo A, Abikhzer G, et al. Submandibular salivary gland transfer: a pitfall in head and neck imaging with F-18 FDG PET/CT. Clin Nucl Med 2011;36:712–16 10.1097/RLU.0b013e318219ac4a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lee MK, Sepahdari A, Cohen M. Radiologic measurement of submandibular gland ptosis. Facial Plast Surg 2013;29:316–20 10.1055/s-0033-1349356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Saito N, Nadgir RN, Nakahira M, et al. Posttreatment CT and MR imaging in head and neck cancer: what the radiologist needs to know. Radiographics 2012;32:1261–82; discussion 1282–84 10.1148/rg.325115160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bronstein AD, Nyberg DA, Schwartz AN, et al. Increased salivary gland density on contrast-enhanced CT after head and neck radiation. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1987;149:1259–63 10.2214/ajr.149.6.1259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Murdoch-Kinch CA, Kim HM, Vineberg KA, et al. Dose-effect relationships for the submandibular salivary glands and implications for their sparing by intensity modulated radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2008;72:373–82 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.12.033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]