Abstract

BACKGROUND AND PURPOSE:

The multisegment clot sign has been observed at the site of large-artery occlusion in patients with acute ischemic stroke. This study aimed to assess its occurrence rate and relationship with stroke etiologies in patients with acute intracranial large-artery occlusion.

MATERIALS AND METHODS:

We included consecutive patients with acute ischemic stroke who had acute intracranial large-artery occlusion and underwent perfusion CT within 8 hours after stroke onset. The multisegment clot sign was assessed on dynamic CT angiography derived from perfusion CT. The stroke etiologies were defined by the international Trial of Org 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment criteria. Poisson regression analyses and diagnostic testing were used to investigate the relationship between the multisegment clot sign and stroke etiologies.

RESULTS:

Finally, 194 patients with intracranial large-artery occlusion were enrolled. According to the Trial of Org 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment criteria, 110 (56.7%) patients were diagnosed with cardioembolism; 43 (22.2%), with large-artery atherosclerosis; and 41 (21.1%), with undetermined etiology. The multisegment clot sign was found in 74 (38%) patients. Poisson regression analysis showed that the presence of the multisegment clot sign was significantly higher in patients with cardioembolism than in those with large-artery atherosclerosis (52.7% versus 9.3%; prevalence ratio, 1.53; 95% confidence interval, 1.03–2.90; P = .037). For determined etiologies, the sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive values of the multisegment clot sign for predicting cardioembolism were 52.7%, 90.7%, 93.5%, and 42.9%, respectively.

CONCLUSIONS:

The presence of the multisegment clot sign on dynamic CTA specifically indicates intracranial large-artery occlusion caused by an embolism from a cardiac source, which may be useful for acute management and secondary prevention of stroke.

Intracranial large-artery occlusion (LAO) is a common cause of acute ischemic stroke and may cause severe disability and mortality.1 LAO is estimated to account for 20%–50% of ischemic stroke and varies in different populations.2 Endovascular therapy has been recommended as a standard treatment for acute proximal cerebral LAO.3 Recently, the success of endovascular therapy has been reported to be affected by the sources of the vessel occlusion.4 Cardioembolism (CE) and large-artery atherosclerosis (LAA) are the 2 common causes of LAO. However, differentiating these 2 etiologies is often challenging, especially in an acute clinical scenario where a quick treatment decision must be made after acute ischemic stroke.5

Attempts have been made to address this challenge by implementing advanced brain imaging. Recent MR imaging studies suggest that both the 2-layered susceptibility vessel sign on T2*-weighted images and the overestimation ratio of the susceptibility vessel sign can predict CE.6,7 Another study showed that the branching-site occlusion on digital subtraction angiography was highly associated with CE.4 Because CT is available in most emergency departments of comprehensive stroke centers, perfusion CT is routinely performed before reperfusion treatment. Given that DSA is an invasive procedure and MR imaging has its contraindications, dynamic CT angiography derived from CTP is a more ideal and convenient technique, which can provide dynamic angiographic and parenchymal information. Therefore, it is worthwhile to investigate its role in predicting CE.

Recently, on the basis of dynamic CTA derived from CTP, which uses the extended image-acquisition time span, we noticed a phenomenon of 1 clot presenting as multiple segments. Because pathology studies have shown that the clot from CE has a higher proportion of red blood cells than LAA clots and is more prone to dissociate itself into multiple segments,8 we thought that the presence of this sign might be associated with cardiac-origin clots.

In the present study, we introduce the definition of the multisegment clot (MSC) sign on dynamic CTA and aim to evaluate the association between the MSC sign and stroke etiologies.

Materials and Methods

Patients

This study was approved by the human ethics committee of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University, School of Medicine. We retrospectively reviewed our prospectively collected data base for consecutive patients with acute ischemic stroke who received thrombolytic therapy with or without endovascular therapy between May 2009 to March 2016. We enrolled patients under the following conditions: 1) They underwent CTP within 8 hours after stroke onset, 2) had occlusion of the internal carotid artery or middle cerebral artery up to the proximal M2 segment, and 3) had acute ischemic stroke with CE, LAA, or undetermined etiology. Patients who had poor image quality because of motion artifacts or incomplete images were excluded.

Clinical Data

Baseline clinical variables were recorded, including demographics, risk factors (smoking, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, or a history of stroke/TIA or atrial fibrillation), prior antiplatelet usage, prior warfarin (Coumadin) use, onset-to-imaging time, baseline National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale score, and laboratory and radiologic data. The stroke etiologies were determined according to the Trial of Org 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment (TOAST).5 CE needed to fit evidence of cardiac disease that has a potential for embolism and no evidence of stenosis of ≥50% on relevant intracranial or extracranial large arteries.5 LAA needed to fit clinical and brain imaging findings of either severe (>50%) stenosis or occlusion of a major brain artery or branch cortical artery, presumably due to atherosclerosis, and no potential sources of cardiogenic embolism. Undetermined etiology included the following: 1) ≥2 potential causes of stroke, or 2) no likely etiology determined despite an extensive evaluation, or 3) no cause found due to inadequate evaluation.5

Imaging Protocol

Baseline CTP was performed on a 64-slice CT scanner (Somatom Definition Flash; Siemens, Erlangen, Germany), including an NCCT scan (120 kV, 320 mA, contiguous 5-mm axial slices, 7-second acquisition time) and volume CTP (100 mm in the z-axis, 4-second delay after the start of contrast medium injection, 74.5-second total imaging duration, 80 kV, 120 mA, 1.5-mm slice thickness, 32 × 1.2 mm collimation). Volume CTP consisted of 26 consecutive spiral acquisitions of the brain. All 26 scans were divided into 4 parts: 1) 2 scans with 3-second cycle time; 2) 15 scans with 1.5-second cycle time; 3) 4 scans with 3-second cycle time; and 4) 5 scans with 6-second cycle time. Axial slice coverage was 150 mm. A 60-mL bolus of contrast medium, Imeron (iopamidol; Bracco, Milan, Italy), with a single injection at a flow rate of 6 mL/s was followed by a 20-mL saline chaser at 6 mL/s.

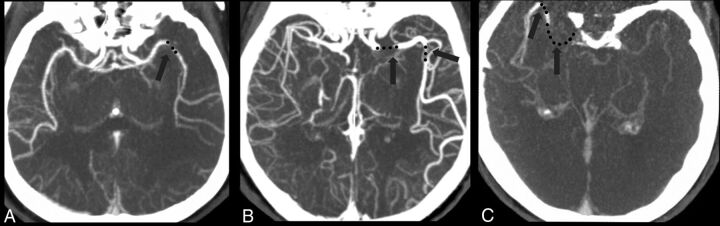

Assessment of the MSC Sign

Thick-slab reformatted dynamic CTA images were reconstructed from CTP source images in axial, coronal, and sagittal planes with a 30-mm-thick maximum intensity projection on an Advantage Windows Workstation (GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, Wisconsin). The MSC sign was defined as >1 occlusion site on 26-phase dynamic CTA, including angiographic information of both the early and late phases (Figure). We assessed the MSC sign on all 26 phases by adjusting the planes forward and backward on dynamic CTA to ensure every occlusion site. Two experienced neurologists blinded to the patient information assessed the MSC sign with rater discrepancies settled by consensus discussion.

FIGURE.

Examples of the multisegment clot sign on dynamic CT angiography derived from CT perfusion. A, One patient with LAA had 1 clot (black dot) presenting as 1 segment in the middle cerebral artery, which was categorized as a 1-segment clot. B, One patient with CE had 2 segments of the clot on a delayed phase of dynamic CTA, which was categorized as a multisegment clot. C, Another patient with CE had 2 segments of the clot on a late delayed phase of dynamic CTA, which was also categorized as a multisegment clot.

Statistical Analysis

The patients were trichotomized according to the TOAST criteria or dichotomized according to the presence of the MSC sign. The κ statistic value was used to assess intraobserver and interobserver variability for evaluating the MSC sign. Clinical characteristics and imaging profiles were summarized by medians with interquartile range for continuous variables, and percentages for categoric variables. For continuous variables, the Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare difference between 2 groups, and the Kruskal-Wallis test was used to compare difference among 3 groups. For categoric variables, the χ2 test was used to compare differences among groups. Variables with a P < .2 in univariate regression analyses were included in Poisson regression or a binary logistic regression model. Diagnostic parameters, including sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive values, were calculated to assess the prognosis of the MSC sign in differentiating CE from other etiologies. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS, Version 22.0 (IBM, Armonk, New York) and STATA 14.0 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas). A P value < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

A total of 194 patients were finally included (112 men; median age, 73 years; interquartile range, 60–80 years; median baseline NIHSS score, 13; interquartile range, 8–17). Among them, 110 (56.7%) were in the CE group, 43 (22.2%) were in the LAA group, and 41 (21.1%) were in the undetermined etiology group. The MSC sign was identified in 74 (38%) patients. The intraobserver and interobserver κ values for the detection of the MSC sign were 0.989 and 0.956, respectively.

Table 1 shows that patients with the MSC sign had lower blood glucose levels (P = .017), lower leukocyte counts (P = .028), and higher rates of cardioembolism (78.4% versus 43.3%, P < .001) compared with those without the MSC sign. Besides, patients with the MSC sign were inclined to be older (P = .097) and have lower rates of diabetes mellitus (P = .072). Moreover, atrial fibrillation was a significant independent predictor of the presence of the MSC sign after adjusting for age, onset to imaging time, blood glucose levels, leukocyte counts, hypertension, and diabetes mellitus in the binary logistic regression model (odds ratio, 3.704; 95% CI, 1.761–7.790; P = .001). The area under the curve generated from the final regression model to predict the presence of MSC sign was 0.72.

Table 1:

Comparison of baseline characteristics between patients with and without the MSC signa

| No MSC (n = 120) | MSC (n = 74) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr) | 70 (60–79) | 76 (63–80) | .097 |

| Male sex (No.) (%) | 71 (59.2%) | 41 (55.4%) | .606 |

| Baseline NIHSS score | 13 (7–16) | 13 (9–17) | .217 |

| Systolic BP (mm Hg) | 149 (133–162) | 150 (137–169) | .288 |

| Diastolic BP (mm Hg) | 80 (71–90) | 79 (71–94) | .975 |

| Onset-to-imaging time (min) | 185 (115–236) | 152 (92–223) | .105 |

| Laboratory data | |||

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 7.10 (6.28–8.30) | 6.60 (5.78–7.36) | .017 |

| Leukocytes (10E9/L) | 8.30 (6.60–10.53) | 7.10 (5.75–9.25) | .028 |

| Percentage of neutrophils | 75.75 (64.63–83.40) | 74.70 (61.50–84.65) | .874 |

| Platelets (10E9/L) | 183 (145–216) | 171 (130–209) | .305 |

| Risk factors | |||

| Smoking (No.) (%) | 42 (35.0%) | 23 (31.1%) | .574 |

| Hypertension (No.) (%) | 73 (60.8%) | 52 (70.3%) | .182 |

| Diabetes mellitus (No.) (%) | 27 (22.5%) | 9 (12.2%) | .072 |

| Hyperlipidemia (No.) (%) | 46 (38.3%) | 27 (36.5%) | .796 |

| History of stroke/TIA (No.) (%) | 21 (17.5%) | 11 (14.9%) | .631 |

| Atrial fibrillation (No.) (%) | 53 (44.2%) | 56 (75.7%) | <.001 |

| Prior antiplatelet use (No.) (%) | 19 (15.8%) | 14 (18.9%) | .578 |

| Prior Coumadin use (No.) (%) | 4 (3.3%) | 6 (8.1%) | .260 |

| Stroke etiologies | |||

| CE (No.) (%) | 52 (43.3%) | 58 (78.4%) | <.001 |

| LAA (No.) (%) | 39 (32.5%) | 4 (5.4%) | <.001 |

| Undetermined etiology (No.) (%) | 29 (24.2%) | 12 (16.2%) | .188 |

Note:—BP indicates blood pressure.

Data are expressed as median (Q1–Q3) for continuous variables.

Table 2 shows the clinical and image characteristics of the 3 groups. Univariate analysis showed that age, sex, baseline NIHSS score, smoking, atrial fibrillation, and the presence of the MSC sign were significantly different among the 3 groups. Patients with CE were older and had lower proportions of men and current smokers and higher baseline NIHSS scores compared with those with LAA (P < .05). Moreover, the rate of the MSC sign was higher in patients with CE than in those with LAA or undetermined etiology (52.7%, 9.3%, and 29.3%, respectively; P < .001).

Table 2:

Comparison of baseline characteristics among the 3 groups

| CE (n = 110) | LAA (n = 43) | Undetermined Etiology (n = 41) | Pa | Pb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr) | 74 (66–80) | 67 (56–79) | 63 (59–79) | .016 | .016 |

| Male sex (No.) (%) | 52 (47.3%) | 32 (74.4%) | 28 (68.3%) | .003 | .002 |

| Baseline NIHSS score | 14 (10–18) | 10 (5–14) | 14 (9–18) | .002 | .001 |

| Systolic BP (mm Hg) | 150 (133–168) | 154 (138–164) | 144 (129–155) | .172 | .450 |

| Diastolic BP (mm Hg) | 79 (71–94) | 80 (72–93) | 78 (68–89) | .370 | .955 |

| Onset-to-imaging time (min) | 154 (92–225) | 163 (112–230) | 197 (134–262) | .128 | .540 |

| Prior antiplatelet use (No.) (%) | 19 (17.3%) | 6 (14.0%) | 8 (19.5%) | .790 | .618 |

| Risk factors | |||||

| Smoking (No.) (%) | 28 (25.5%) | 21 (48.8%) | 16 (39.0%) | .016 | .005 |

| Hypertension (No.) (%) | 73 (66.4%) | 29 (67.4%) | 23 (56.1%) | .451 | .899 |

| Diabetes mellitus (No.) (%) | 20 (18.2%) | 11 (25.6%) | 5 (12.2%) | .285 | .306 |

| Hyperlipidemia (No.) (%) | 41 (37.3%) | 15 (34.9%) | 17 (41.5%) | .818 | .783 |

| History of stroke/TIA (No.) (%) | 19 (17.3%) | 9 (20.9%) | 4 (9.8%) | .365 | .599 |

| Atrial fibrillation (No.) (%) | 98 (89.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 11 (26.8%) | <.001 | <.001 |

| MSC sign (No.) (%) | 58 (52.7%) | 4 (9.3%) | 12 (29.3%) | <.001 | <.001 |

Note:—BP indicates blood pressure.

Data are expressed as median (Q1–Q3) for continuous variables among the 3 groups.

Data are expressed as median (Q1–Q3) for continuous variables between CE and LAA.

Thus, age, sex, smoking, baseline NIHSS score, systolic blood pressure, onset-to-imaging time, and the MSC sign were included in the Poisson regression model to select predictors of CE stroke. It revealed that the presence of the MSC sign (prevalence ratio, 1.53; 95% CI, 1.03–2.90; P = .037) was independently associated with CE after adjustment compared with the LAA (Table 3). The area under the curve generated from the final model based on Poisson regression was 0.84. However, the presence of the MSC sign could not independently predict CE from undetermined etiology after adjustment for age, sex, smoking, baseline NIHSS score, systolic blood pressure, and onset-to-imaging time (prevalence ratio, 1.19; 95% CI, 0.80–1.76; P = .393) (Table 4).

Table 3:

Poisson regression for differentiating CE from LAA

| Variables | PR (95% CI) | P Value |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.01 (0.99–1.02) | .453 |

| Baseline NIHSS score | 1.02 (0.99–1.05) | .195 |

| Male | 0.86 (0.53–1.40) | .552 |

| Smoking | 0.83 (0.48–1.43) | .499 |

| Systolic BP | 1.00 (0.99–1.01) | .550 |

| Onset-to-imaging time | 1.00 (1.00–1.00) | .984 |

| MSC sign | 1.53 (1.03–2.90) | .037 |

Note:—PR indicates prevalence ratio; BP, blood pressure.

Table 4:

Poisson regression for differentiating CE from undetermined etiology

| Variables | PR (95% CI) | P Values |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.00 (0.99–1.02) | .602 |

| Baseline NIHSS score | 1.00 (0.97–1.04) | .784 |

| Male sex | 0.84 (0.53–1.34) | .472 |

| Smoking | 0.94 (0.55–1.60) | .818 |

| Systolic BP | 1.00 (1.00–1.00) | .776 |

| Onset-to-imaging time | 1.00 (1.00–1.00) | .373 |

| MSC sign | 1.19 (0.80–1.76) | .393 |

Note:—PR indicates prevalence ratio; BP, blood pressure.

Among patients with determined etiologies, there were 110 patients with CE and 43 with LAA. The sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive values of the MSC sign for predicting CE were 52.7%, 90.7%, 93.5%, and 42.9%, respectively (Table 5).

Table 5:

Diagnostic testing of the multisegment clot sign for predicting cardioembolism with or without excluding patients with undetermined etiology

| Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | Positive Predictive Value (%) | Negative Predictive Value (%) | Accuracy | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All patients (n = 194) | 52.7 | 81.0 | 78.4 | 56.7 | 64.9 |

| Excluding UE (n = 153) | 52.7 | 90.7 | 93.5 | 42.9 | 63.4 |

Note:—UE indicates undetermined etiology.

Discussion

Our study indicates that conditions of patients with acute LAO with the MSC sign are more likely due to CE rather than LAA. In the current study, the MSC sign was detected in more than half of the patients with CE, and this sign predicted CE with high specificity and a positive predictive value of 90.7% and 93.5%, respectively.

The sensitivity (52.7%) and the specificity (90.7%) of the MSC sign to predict stroke etiologies were similar to the previously reported 2-layered susceptibility vessel sign on T2*WI, and that previous study included only patients with CE and LAA.6 The sensitivity of the MSC sign to predict CE is not high, while the MSC sign exhibited a higher specificity for CE. Thus, we cannot exclude CE in the patients without the MSC sign. However, the high specificity and positive predictive value showed the usefulness of the MSC sign for diagnosing CE, even in patients without known atrial fibrillation.

The underlying mechanism of the MSC sign may be related to clot size, hemodynamic features, and the clot composition. A previous study showed that the CE clot had a larger size and longer walking pathway to occlusion site compared with an LAA clot, which might increase the risk of CE clot collisions on the vessel wall, resulting in splitting of the clot.9 In addition, the CE clot has the hemodynamic feature of passing through high-pressure gradient areas such as a mitral or aortic valve after discharging from a cardiac chamber,10 while beyond the site of stenosis, the blood flow velocity of an LAA clot is relatively slow. This difference may make it easier for the CE clot to divide into pieces than the LAA clot.10 Clot composition may also play a role. A CE clot has a high proportion of erythrocytes, while an LAA clot contains a high composition of fibrin.11–13 Moreover, different from a CE clot, an atherothrombotic clot usually consists of an exterior meshwork of fibrin and platelet aggregates and an interior close-packed array of compressed polyhedral erythrocytes.14,15 As a result, the contrast agent penetrates into the space between separated segments due to clot permeability or collateral circulation and is presented as the MSC sign on dynamic CTA.

Currently, guidelines recommend endovascular therapy for patients with acute LAO, while different devices and combined therapy have been introduced when treating patients with different etiologies.16 Rapid identification of the etiology is crucial for emergent management. With a short acquisition time and wide use of CTP, the assessment of the MSC sign is quick and easy. By providing interventionists with additional information about occlusion etiology, the MSC sign may help decision-making for endovascular procedures and even advance the secondary prevention strategy.17,18 The etiology of acute LAO seems related to stent retriever refractoriness and some other complications, such as inadvertent detachment, stent retrievers getting stuck, and frequent reocclusions.19–22 The presence of truncal-site occlusion reflecting intracranial atherosclerosis was associated with a lower chance of stent retriever success, and these patients more frequently required adjunctive therapies, such as stent placement or use of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors.4 Failure of stroke intervention was associated with longer procedural times and delayed recanalization, resulting in larger infarct volumes and worse neurologic outcomes.23 Thus, those patients may require greater monitoring for stroke progression and edema development in the postprocedure period.24 Therefore, stroke etiology provides potentially useful information for neurologists and neurointerventionists involved in acute ischemic stroke treatment.

In the present study, 12 (29.3%) patients in the undetermined etiology group presented with the MSC sign, which could not differentiate CE from undetermined etiology. A previous histologic study found that the features of the clots in patients with undetermined etiology were like those of cardiogenic thrombi.25 Therefore, the presence of the MSC sign in patients with acute ischemic stroke with inexplicit etiology during this hospitalization indicates the importance of the search for the cardiac sources. Anticoagulation is highly effective for reduction of recurrent stroke among patients with atrial fibrillation.26 Our findings suggest that anticoagulation should be considered among patients with the MSC sign.

In clinical practice, CTP is used to provide information about infarct core and penumbra. The advantage of evaluating the MSC sign on dynamic CTA is no additional x-ray exposure and contrast medium usage because it is derived from CTP. CT scanners are more widely available than MR imaging scanners and are commonly located in emergency departments of local hospitals.27 In addition, it is reported that early arterial imaging can overestimate clot length while a late-phase CTA can more accurately delineate the distal thrombus extent.27 The “delayed-vessel sign” on multiphase CTA refers to the presence of an artery distal to the point of occlusion that is absent or poorly opacified on the early angiographic phases but becomes more opacified and denser on the late phases, which can rapidly indicate the presence of an ipsilateral vessel occlusion.28 Moreover, compared with MR imaging, dynamic CTA is less commonly influenced by motion and denture artifacts.

There are several limitations to this study. First, it is a retrospective study, though data were prospectively collected using a stroke registry and CTP protocol. A potential risk of selection bias might exist. Second, the sensitivity of the MSC sign was not high, so we cannot exclude CE in our patients without the MSC sign. Third, it was difficult to assess the thrombi beyond the M2 segment; this issue makes the MSC sign less positive. Fourth, the LAA group did not include patients with potential vulnerable plaque despite <50% stenosis, such as those with carotid intraplaque hemorrhage or enhancing intracranial atherosclerotic plaque.29 Finally, we did not make the histologic comparison of the clots between patients with and without the MSC sign, lacking the information about the nature of different clots.

Conclusions

The presence of the multisegment clot sign on dynamic CTA specifically indicates the cause of CE in patients with acute LAO. In clinical practice, this sign may be helpful for acute management and secondary prevention of ischemic stroke.

ABBREVIATIONS:

- CE

cardioembolism

- LAA

large-artery atherosclerosis

- LAO

intracranial large-artery occlusion

- MSC

multisegment clot

- TOAST

Trial of Org 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment

Footnotes

Disclosures: Zhicai Chen—RELATED: Grant: National Natural Science Foundation of China (81601017) and Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (LQ16H090003).* Min Lou—RELATED: Grant: National Natural Science Foundation of China (81622017 and 81471170) and National Key Research and Development Program of China (2016YFC1301500).* *Money paid to the institution.

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81622017, 81601017, 81400946), the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2016YFC1301500), Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (2017XZZX002-09), and the Natural Science Foundation of Zhejiang Province (LQ16H090003).

The perfusion analysis software (MIStar) used in this study was provided to the site as part of the involvement in the International Stroke Perfusion Imaging Registry (INSPIRE, a study funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia).

References

- 1. Saver JL, Jahan R, Levy EI, et al. ; SWIFT Trialists. Solitaire flow restoration device versus the Merci retriever in patients with acute ischaemic stroke (SWIFT): a randomised, parallel-group, non-inferiority trial. Lancet 2012;380:1241–49 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61384-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gorelick PB, Wong KS, Bae HJ, et al. Large artery intracranial occlusive disease: a large worldwide burden but a relatively neglected frontier. Stroke 2008;39:2396–99 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.505776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Powers WJ, Derdeyn CP, Biller J, et al. ; American Heart Association Stroke Council. 2015 American Heart Association/American Stroke Association Focused Update of the 2013 Guidelines for the Early Management of Patients with Acute Ischemic Stroke Regarding Endovascular Treatment: A Guideline for Healthcare Professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 2015;46:3020–35 10.1161/STR.0000000000000074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Baek JH, Kim BM, Kim DJ, et al. Importance of truncal-type occlusion in stentriever-based thrombectomy for acute stroke. Neurology 2016;87:1542–50 10.1212/WNL.0000000000003202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Adams HP, Bendixen BH, Kappelle LJ, et al. Classification of subtype of acute ischemic stroke: definitions for use in a multicenter clinical trial—TOAST. Trial of Org 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment. Stroke 1993;24:35–41 10.1161/01.STR.24.1.35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Yamamoto N, Satomi J, Tada Y, et al. Two-layered susceptibility vessel sign on 3-Tesla T2*-weighted imaging is a predictive biomarker of stroke subtype. Stroke 2015;46:269–71 10.1161/STROKEAHA.114.00722771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zhang R, Zhou Y, Liu C, et al. Overestimation of susceptibility vessel sign: a predictive marker of stroke cause. Stroke 2017;48:1993–96 10.1161/STROKEAHA.117.016727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kaesmacher J, Boeckh-Behrens T, Simon S, et al. Risk of thrombus fragmentation during endovascular stroke treatment. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2017;38:991–98 10.3174/ajnr.A5105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hart RG, Halperin JL. Atrial fibrillation and stroke: concepts and controversies. Stroke 2001;32:803–08 10.1161/01.STR.32.3.803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jung JM, Kwon SU, Lee JH, et al. Difference in infarct volume and patterns between cardioembolism and internal carotid artery disease: focus on the degree of cardioembolic risk and carotid stenosis. Cerebrovasc Dis 2010;29:490–96 10.1159/000297965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kang DW, Jeong HG, Kim DY, et al. Prediction of stroke subtype and recanalization using susceptibility vessel sign on susceptibility-weighted magnetic resonance imaging. Stroke 2017;48:1554–59 10.1161/STROKEAHA.116.016217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kim SK, Yoon W, Kim TS, et al. Histologic analysis of retrieved clots in acute ischemic stroke: correlation with stroke etiology and gradient-echo MRI. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2015;36:1756–62 10.3174/ajnr.A4402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sato Y, Ishibashi-Ueda H, Iwakiri T, et al. Thrombus components in cardioembolic and atherothrombotic strokes. Thromb Res 2012;130:278–80 10.1016/j.thromres.2012.04.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tutwiler V, Peshkova AD, Andrianova IA, et al. Contraction of blood clots is impaired in acute ischemic stroke. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2017;37:271–79 10.1161/ATVBAHA.116.308622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cines DB, Lebedeva T, Nagaswami C, et al. Clot contraction: compression of erythrocytes into tightly packed polyhedra and redistribution of platelets and fibrin. Blood 2014;123:1596–603 10.1182/blood-2013-08-523860 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Behme D, Molina CA, Selim MH, et al. Emergent carotid stenting after thrombectomy in patients with tandem lesions. Stroke 2017;48:1126–28 10.1161/STROKEAHA.117.016182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Campbell BC, Christensen S, Levi CR, et al. Comparison of computed tomography perfusion and magnetic resonance imaging perfusion-diffusion mismatch in ischemic stroke. Stroke 2012;43:2648–53 10.1161/STROKEAHA.112.660548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Payabvash S, Souza LC, Kamalian S, et al. Location-weighted CTP analysis predicts early motor improvement in stroke: a preliminary study. Neurology 2012;78:1853–59 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318258f799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Matias-Guiu JA, Serna-Candel C, Matias-Guiu J. Stroke etiology determines effectiveness of retrievable stents. J Neurointerv Surg 2014;6:e11 10.1136/neurintsurg-2012-010395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Toyoda K, Koga M, Hayakawa M, et al. Acute reperfusion therapy and stroke care in Asia after successful endovascular trials. Stroke 2015;46:1474–81 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.008781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gascou G, Lobotesis K, Machi P, et al. Stent retrievers in acute ischemic stroke: complications and failures during the perioperative period. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2014;35:734–40 10.3174/ajnr.A3746 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kang DH, Kim YW, Hwang YH, et al. Instant reocclusion following mechanical thrombectomy of in situ thromboocclusion and the role of low-dose intra-arterial tirofiban. Cerebrovasc Dis 2014;37:350–55 10.1159/000362435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Khatri P, Abruzzo T, Yeatts SD, et al. ; IMS I and II Investigators. Good clinical outcome after ischemic stroke with successful revascularization is time-dependent. Neurology 2009;73:1066–72 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181b9c847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Chaturvedi S, Campbell B. Predicting failure of acute stroke intervention. Neurology 2016;87:1528–29 10.1212/WNL.0000000000003214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ahn SH, Hong R, Choo IS, et al. Histologic features of acute thrombi retrieved from stroke patients during mechanical reperfusion therapy. Int J Stroke 2016;11:1036–44 10.1177/1747493016641965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ruff CT, Giugliano RP, Braunwald E, et al. Comparison of the efficacy and safety of new oral anticoagulants with warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation: a meta-analysis of randomised trials. Lancet 2014;383:955–62 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62343-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mortimer AM, Simpson E, Bradley MD, et al. Computed tomography angiography in hyperacute ischemic stroke: prognostic implications and role in decision-making. Stroke 2013;44:1480–88 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.679522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Byrne D, Sugrue G, Stanley E, et al. Improved detection of anterior circulation occlusions: the “delayed vessel sign” on multiphase CT angiography. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2017;38:1911–16 10.3174/ajnr.A5317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rai S, Thaler DE, Salehi P, et al. More to atherosclerosis than stenosis: symptomatic carotid artery with intraplaque hemorrhage. Stroke 2017;48:e104–07 10.1161/STROKEAHA.117.016923 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]