Abstract

Objectives

To determine factors associated with parents who plan to vaccinate their children against influenza next year, especially those who did not vaccinate against influenza last year using a global survey.

Study design

A survey of caregivers accompanying their children aged 1-19 years old in 17 pediatric emergency departments in 6 countries at the peak of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. Anonymous online survey included caregiver and child demographic information, vaccination history and future intentions, and concern about the child and caregiver having COVID-19 at the time of emergency department visit.

Results

Of 2422 surveys, 1314 (54.2%) caregivers stated they plan to vaccinate their child against influenza next year, an increase of 15.8% from the previous year. Of 1459 caregivers who did not vaccinate their children last year, 418 (28.6%) plan to do so next year. Factors predicting willingness to change and vaccinate included child's up-to-date vaccination status (aOR 2.03, 95% CI 1.29-3.32, P = .003); caregivers' influenza vaccine history (aOR 3.26, 95% CI 2.41-4.40, P < .010), and level of concern their child had COVID-19 (aOR 1.09, 95% CI 1.01-1.17, P = .022).

Conclusions

Changes in risk perception due to COVID-19, and previous vaccination, may serve to influence decision-making among caregivers regarding influenza vaccination in the coming season. To promote influenza vaccination among children, public health programs can leverage this information.

Keywords: vaccine hesitancy, parental attitudes

Abbreviations: COVIPAS, International COVID-19 Parental Attitude Study; COVID-19, Coronavirus disease 2019; ED, Emergency department

See related article, p 271

Seasonal influenza is a major public health problem, responsible for thousands of deaths every year, including children.1 Despite the wide availability of seasonal influenza vaccines and clear guidelines for who should be immunized, vaccine uptake remains low in most countries.2 With the unprecedented coronavirus severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 illness, now called coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), which currently lacks a publicly available vaccine, public health authorities worldwide recommended numerous strategies to reduce spread, including reducing physical encounters and wearing masks. These measures have had variable success in curtailing the spread of the virus around the world. Vaccines are likely to provide the best protection from contracting the illness, and there are currently more than 100 projects centered on the development of a vaccine and many have entered clinical trials.3

There is a high likelihood that community transmission of COVID-19 will continue into the next influenza epidemic,4 complicating diagnoses and further increasing the burden on healthcare systems.5 To mitigate these issues, vaccinating large parts of the population against influenza in late 2020 is a key goal of public health officials.

The objective of this timely survey study was to determine, during the COVID-19 peak pandemic, caregiver intentions toward influenza vaccination of their children, as well as themselves. To better understand how COVID-19 has influenced attitudes toward influenza vaccination, we specifically aimed to describe characteristics of caregivers who intend to immunize their children in 2020-2021 despite the child not receiving influenza immunization in the previous year. Understanding caregivers' attitudes can help public health officials plan targeted messaging to parents to promote influenza vaccination in the upcoming season.

Methods

Study Cohort

This study is part of a larger COVID-19 Parental Attitude Study (COVIPAS) study, surveying caregivers of children presenting for emergency care, in the era of COVID-19. Caregivers who arrived to 17 pediatric emergency departments (EDs) in the US (Seattle, Tacoma, Los Angeles, Dallas, Atlanta), Canada (Vancouver, Toronto, Saskatoon, Edmonton, Calgary), Israel (Shamir), Japan (Tokyo), Spain (Barcelona), and Switzerland (Zurich, Bern, Geneva, Bellinzona) were asked to participate, using posters in waiting areas and patient rooms. For infectious control purposes, respondents used their own smartphones to complete the survey by logging into a secured online platform based on REDCap metadata-driven software (Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tennessee). Several intuitional review boards (in Switzerland and Spain) provided a waiver of consent such that responding to the survey was considered consent to participate.

Languages available to complete the study were English, French, German, Italian, Spanish, Hebrew, and Japanese. Although sites joined recruitment in a staggered fashion, surveys were obtained between March 27 and June 30, 2020. Only one caregiver per family was asked to complete the survey.

For this study, analyses were limited to surveys completed by parents or caregivers, for patients older than 1 year and younger than 19 years of age. Children younger than 1 year were excluded, as these children might not have been eligible to receive influenza vaccine during the previous year. Vaccination against influenza is available for children older than 6 months in all countries that this survey took place.

Exposures

Outcome Measures

The study-specific questionnaire was developed to include questions regarding demographic characteristics, information about the ED visit, and attitudes around COVID-19. Respondents also were asked about their child's vaccination history excluding influenza. Children were considered up-to-date on their vaccinations if the caregiver chose the response: “My child has received all recommended vaccines/immunizations on the schedule suggested by our doctor.”

We asked caregivers to answer 4 questions about influenza vaccination separate than the vaccination schedule: (1) “Was your child immunized for influenza (flu) in the last 12 months?” (2) “Have you been immunized for influenza (flu) in the last 12 months?” (3) “Do you plan to immunize your child for influenza (flu) next year?” and (4) “Do you plan to immunize yourself for influenza (flu) next year?”

The survey was developed to assess opinions caregivers may have or actions they may take during the pandemic. Literature related to reports from the severe acute respiratory syndrome epidemic in 2002-2003 was reviewed and considerations regarding public health measures in mid-March 2020, during the COVID-19 pandemic were reflected in the survey. All items of the survey, including those presented in this report, were evaluated a priori by 10 individuals representing the target group and 10 healthcare providers working in the ED environment. The final version of the survey is based on the feedback and test clarity generated from these 2 groups.

Statistical Analyses

Basic descriptive statistics and frequencies were used to describe all variables. We compared survey data from caregivers who stated whether they plan to immunize or not immunize their children against influenza in the coming year. We then compared caregivers who did not immunize for influenza their children last year and compared those that said they do or do not plan to immunize their children for influenza next year. To determine which factors were significantly associated with caregiver decision-making to vaccinate next year despite not doing so last year, we used bivariate analyses: the Mann–Whitney U test was used for comparing non-normal continuous variables, independent t tests were used for comparing normally-distributed continuous variables, and χ2 or Fisher exact tests were used for categorical variables. Multivariable logistic regression was used to estimate the aORs of agreeing to immunize against influenza in the coming year using all the variables that showed a level of P < .100 in the bivariate analyses. All analyses were conducted with R, version 3.5.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). A P value less than .05 in the multivariate analysis was considered statistically significant.

Results

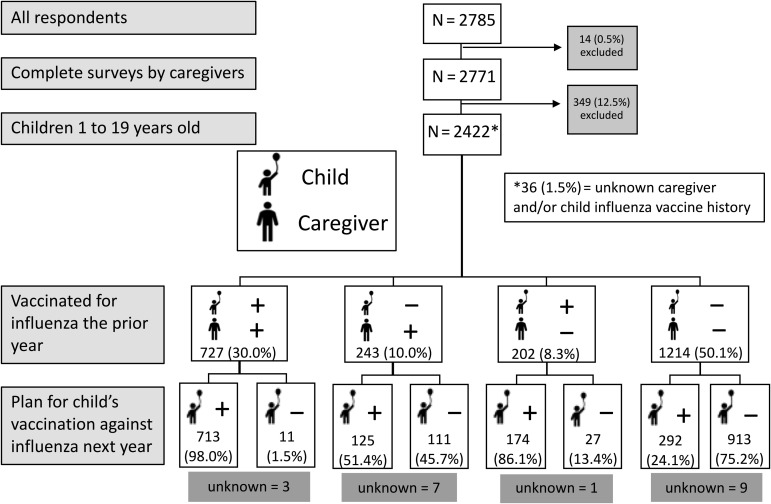

A total of 2785 surveys were completed online. Seven (0.3%) were excluded because the surveys were incomplete, 7 (0.3%) were completed by the patient, 343 (12.3%) were for a patient younger than 1 year of age, 3 (0.1%) for patients older than 19 years old, and 3 (0.1%) with an unspecified patient age (Figure 1 ). Some participants abstained from answering certain questions, accounting for a small number of unknown responses to each question. The final study sample included 2422 respondents: 2350 parents (97.0%), 67 other caregivers, and 5 respondents who did not specify their relationship to the child. Median age of caregivers was 40.0 (SD 7.6) years and median age of the child was 8.3 (SD 4.6) years.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of caregivers' decision to plan to vaccinate their children against influenza next year grouped by their decision to vaccinate themselves and their children against influenza last year. Fourteen surveys were excluded for incomplete responses or surveys filled out by children; 349 surveys excluded of children younger than 1 year old (n = 343), older than 19 years old (n = 3), or did not specify their age (n = 3) at time of survey completion. Unknown are children whose vaccination plan was unspecified.

A total of 1314 (54.3%) respondents stated they intend to vaccinate their children against influenza in the coming 12 months, an increase of 15.9% compared with those that reported an influenza vaccine for their child in the past 12 months (Figure 1). As many as 42 of 2422 (1.7%) respondents did not specify their intention to vaccinate their child and 1394 of 2393 (58.3%) respondents stated they planned to obtain the vaccine for themselves next influenza season, compared with 974 (40.6%) in the past year (Table I ).

Table I.

Comparison between caregivers who plan to vaccinate their children and those who do not plan to vaccinate against influenza

| Questions caregivers were asked | Number of surveys (n = 2422) | Population | Do not plan to vaccinate against influenza (n = 1066) | Plan to vaccinate against influenza (n = 1314) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child's mean age, y (SD) | 2422 | 8.6 (4.6) | 8.7 (4.3) | 8.4 (4.8) | .237 |

| Child's sex female | 2418 | 1163 (48.1%) | 515 (48.3%) | 629 (47.9%) | .841 |

| Child has chronic illness | 2392 | 360 (15.1%) | 105 (9.8%) | 250 (19.0%) | <.001 |

| Child uses chronic medication use | 2392 | 440 (18.4%) | 136 (12.8%) | 298 (22.7%) | <.001 |

| Who completed the survey | 2417 | .165 | |||

| Father | 605 (25.0%) | 285 (26.7%) | 308 (23.4%) | ||

| Mother | 1745 (72.2%) | 751 (70.5%) | 966 (73.5%) | ||

| Other∗ | 67 (2.8%) | 27 (2.5%) | 38 (2.9%) | ||

| Caregiver's age, y (SD) | 2383 | 40.2 (7.6) | 40.6 (7.4) | 40.0 (7.6) | .056 |

| Caregivers with higher education | 2365 | 1819 (76.9%) | 761 (71.4%) | 1038 (79.0%) | <.001 |

| Child vaccinations up to date | 2729 | 2188 (91.5%) | 920 (86.3%) | 1244 (94.7%) | <.001 |

| Child received flu vaccine in last 12 mo | 2390 | 931 (39.0%) | 38 (3.6%) | 888 (67.6%) | <.001 |

| Caregiver received flu vaccine in last 12 mo | 2401 | 974 (40.6%) | 122 (11.4%) | 842 (64.1%) | <.001 |

| Caregiver plans on receiving flu vaccine next year | 2393 | 1394 (58.3%) | 171 (16.0%) | 1213 (92.3%) | <.001 |

| Mean score 10-point Likert scale—caregiver concerned their child has COVID-19 (SD) | 2355 | 1.90 (2.84) | 1.79 (2.69) | 1.97 (2.93) | .129 |

| Mean score 10-point Likert scale—caregiver concerned their child has influenza (SD) | 2331 | 1.17 (2.31) | 1.14 (2.18) | 1.17 (2.39) | .761 |

| Mean score 10-point Likert scale—caregiver concerned they have COVID-19 (SD) | 2343 | 1.84 (2.72) | 1.78 (2.63) | 1.86 (2.77) | .493 |

| Mean score 10-point Likert scale—caregivers concerned they have influenza (SD) | 2327 | 0.90 (1.99) | 0.87 (1.84) | 0.90 (2.08) | .667 |

| Mean score 10-point Likert scale—caregivers concerned about missing work (SD) | 2319 | 2.71 (3.48) | 2.48 (3.35) | 2.87 (3.55) | .007 |

| Mean score 10-point Likert scale—caregivers concerned about child missing school (SD) | 2328 | 2.98 (3.52) | 2.79 (3.43) | 3.10 (3.57) | .037 |

| Caregivers believe that social distancing is worthwhile | 2398 | 2246 (93.7%) | 965 (90.5%) | 1251 (95.2%) | <.001 |

Other includes grandparents, siblings, stepparents, foster parents, and aunts/uncles.

Values in bold are statistically significant.

Table I provides demographic information including a comparison between caregivers who plan to vaccinate for influenza in the coming season and those who do not. The greatest likelihood of planning to vaccinate the child next year was if the caregiver planned to vaccinate themselves in the upcoming year (1213/2422; 50.1% of children). Caregivers were more likely to suggest they will immunize next year if they had education beyond high school, if the child had a chronic illness or took medications regularly, if the child was up-to-date on their vaccines other than influenza according to their country-specific vaccination schedule, or if the child or caregiver received influenza vaccine the previous year.

Of 1459 caregivers who did not vaccinate their children against influenza in the last year, 418 (28.6%) indicated they plan to vaccinate next season, 1025 (70.3%) did not vaccinate last year and will not vaccinate this year, and 16 (1.1%) abstained from answering. Only 38 of 2422 (1.6%) vaccinated their child last year but do not plan to do so next year.

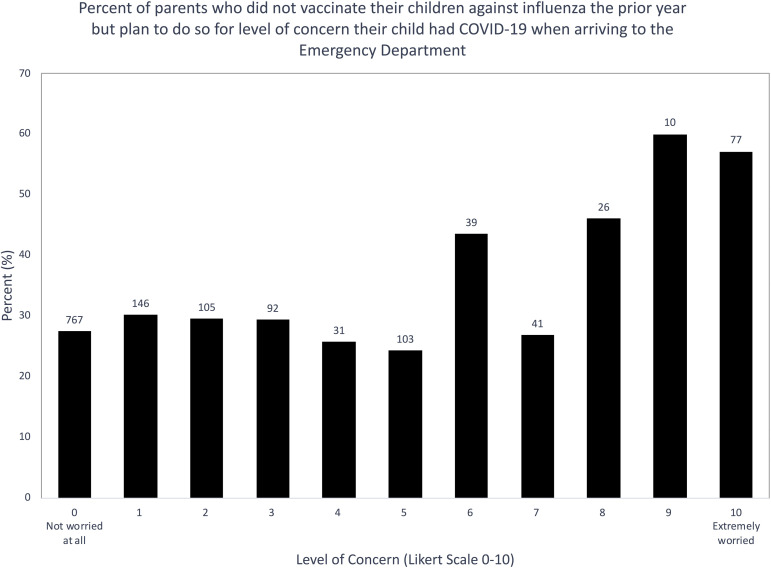

Most caregivers were not concerned about their child having COVID-19 when coming to the EDs in the 6 countries where this survey took place, and we found a significant correlation between level of concern and plan to vaccinate against influenza (P = .037; Figure 2 [available at www.jpeds.com]).

Figure 2.

Percent of caregivers who did not vaccinate their child against influenza last year but plan on having their child vaccinated next year by worry that child has COVID-19. Percentages are based on respondents who disclosed their vaccination plan and their level of COVID-19 worry (n = 1437). χ2 test used for frequencies; χ2 = 19.3, df = 10, P = .037.

Table II describes characteristics of caregivers who did not vaccinate the child last year but plan to vaccinate their child against influenza in the coming year. Caregivers were more likely to change from non-vaccination last year to vaccination in the coming year when they had education more than high-school, they took the vaccine themselves or planning to get vaccinated themselves next year, had a child with an up-to-date vaccination schedule excluding influenza vaccines or were worried their child may have COVID-19 or influenza during the visit in the ED.

Table II.

Factors associated with caregivers who did not vaccinate their child against influenza in the past 12 months but who plan to have their child immunized against influenza next year

| Questions caregivers were asked | Non-flu vaccinators who do not plan to vaccinate against influenza (n = 1025) | Non-flu vaccinators who plan to vaccinate against influenza (n = 418) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Child's mean age, y (SD) | 8.7 (4.3) | 9.2 (4.6) | .091 |

| Child's sex female | 492 (48.0%) | 192 (45.9%) | .357 |

| Child has chronic illness | 100 (9.76%) | 50 (12.0%) | .254 |

| Child uses chronic medication | 130 (12.7%) | 66 (15.8%) | .149 |

| Who completed the survey | .263 | ||

| Father | 274 (26.7%) | 102 (24.4%) | |

| Mother | 723 (70.5%) | 299 (71.5%) | |

| Other∗ | 25 (2.4%) | 16 (3.8%) | |

| Caregiver's age, y (SD) | 40.7 (7.4) | 40.7 (7.6) | .989 |

| Caregivers with higher education | 732 (71.4%) | 328 (78.5%) | .005 |

| Child vaccinations up to date | 885 (86.3%) | 393 (94.0%) | <.001 |

| Caregiver received flu vaccine in last 12 mo | 111 (10.8%) | 125 (29.9%) | <.001 |

| Caregiver plans on receiving flu vaccine next year | 166 (16.2%) | 389 (93.1%) | <.001 |

| Caregiver would vaccinate their child against COVID-19 if a vaccine existed | 492 (48.0%) | 337 (80.6%) | <.001 |

| Mean score 10-point Likert scale—caregivers concerned their child has COVID-19 (SD) | 1.74 (2.65) | 2.18 (3.10) | .012 |

| Mean score 10-point Likert scale—caregivers concerned their child has influenza (SD) | 1.13 (2.16) | 1.54 (2.71) | .006 |

| Mean score 10-point Likert scale—caregivers concerned they have COVID-19 (SD) | 1.76 (2.61) | 2.11 (2.95) | .035 |

| Mean score 10-point Likert scale—caregivers concerned they have influenza (SD) | 0.85 (1.82) | 1.19 (2.37) | .012 |

| Mean score 10-point Likert scale—caregivers concerned about child missing school (SD) | 2.75 (3.40) | 3.29 (3.66) | .012 |

| Mean score 10-point Likert scale—caregivers concerned about missing work (SD) | 2.46 (3.33) | 3.17 (3.71) | .001 |

| Caregiver believes social distancing during COVID-19 is worthwhile | 929 (90.6%) | 395 (94.5%) | .030 |

Other includes grandparents, siblings, stepparents, foster parents, and aunts/uncles.

Values in bold are statistically significant.

In the multivariate logistic regression analysis (Table III ), the following factors predicted a willingness to change from not vaccinating the previous year to vaccinating their child next year: children were up-to-date with non-influenza vaccinations (aOR 2.03, 95% CI 1.29-3.32, P = .003); caregivers received influenza vaccine last year (aOR 3.26, 95% CI 2.41-4.40, P < .010); and caregivers were worried their child had COVID-19 in the ED (aOR 1.09, 95% CI 1.01-1.17, P = .022). Unlike the bivariate analysis, caregivers with higher than high-school education were less likely to change from non-vaccination in the previous year to vaccination in the coming year (aOR 0.71, 95% CI 0.52-0.96, P = .028).

Table III.

Predictors of caregivers who didn't vaccinate their child against influenza for their child receive a flu vaccine next year identified by multivariate logistic regression analysis

| Questions caregivers were asked | aOR | 95% CI | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Child's age | 1 | 0.99-1.00 | .205 |

| Caregivers with higher education | 0.71 | 0.52-0.96 | .028 |

| Child vaccinations are up to date | 2.03 | 1.29-3.32 | .003 |

| Caregivers received flu vaccine last year | 3.26 | 2.41-4.40 | <.01 |

| Caregiver's worry that child has COVID-19 | 1.09 | 1.01-1.17 | .022 |

| Caregiver's worry that they have COVID-19 | 0.994 | 0.923-1.07 | .863 |

Values in bold are statistically significant.

Discussion

An annual influenza vaccination is recommended by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices for all people 6 months and older who do not have contraindications to vaccination.2 Although influenza vaccine effectiveness is hard to determine in advance (was 45% in the US in 2019-2020 season),2 it is overall an effective, minimally invasive, and affordable protective measure against influenza disease and its complications. Reducing influenza illness is important to mitigate morbidity in the population and the burden on hospitals with ongoing COVID-19 illnesses. However, a 2019 survey reported that 6.1% of US parents are hesitant about routine childhood vaccines, and more than one-quarter (26%) are unsure about flu vaccines.6 Identifying predictors for vaccinating children against influenza in the upcoming season may have greater importance than in previous years.7

Behavioral changes related to COVID-19, including social distancing, hand washing, and wearing a mask, will impact influenza spread in the coming year,3 and it is unclear how relaxation of social distancing measures will influence the spread of influenza. Coinfection of COVID-19 and other respiratory pathogens, including influenza, occurred in a significant subset of patients with COVID-198 , 9 and a case report from China describing coinfection with COVID-19 and influenza A virus represent the difficulty in differentiating other causes of respiratory illness from COVID-19.10 The Director of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention predicted that “we're going to have a flu epidemic and coronavirus epidemic at the same time” and that the combination of the 2 will be “more difficult and potentially complicated.”4 Combined influenza and COVID-19 pandemics could result in considerable morbidity and mortality, stressing the health system,3 , 7 and a global interest (as seen through Google trends) in pneumococcal and influenza vaccines during February to March, 2020, has been reported.11

In our global survey of primarily parents attending pediatric EDs, a significant shift in parents' plan to vaccinate against influenza in the season following COVID-19 pandemic was noted. A total of 54.3% survey respondents plan to vaccinate for influenza and 29.0% (418/1443) of caregivers who did not vaccinate last year report a change in plan to do so next year, adding to the protection of their children and reducing the chance of transmission to others. We report that caregivers who plan to vaccinate themselves are very likely to vaccinate their children and predictors for caregivers to plan to vaccinate after not doing so last year include children that have up-to-date vaccinations other than influenza, if the caregiver received influenza vaccine last year, and if they were worried their child had COVID-19.

Seasonal influenza epidemics result in tens of millions of cases, and we have recently reported that caregivers in 14 EDs are likely to provide their children with a COVID-19 vaccine if it becomes available (unpublished data, Goldman et al, 2020). Ensuring influenza vaccine acceptance and uptake in children may also serve public health in promoting COVID-19 vaccines, when those become available.7

More than 70 independent barriers are associated with vaccine hesitancy and include psychological barriers (such as perceived risk, utility, and social benefit); contextual barriers (such as access to healthcare services); and lifestyle barriers (such as smoking, drinking, and physical activity).12 Trust in healthcare providers' advice and mainstream medicine, influence of social network and social norms, knowledge sources about vaccines, and general views toward health are key factors in parental vaccine decision-making.13 Vaccine risk-perception of parents is often complicated by cognitive bias and personal experience14 and in our cohort, caregivers were most likely to report plans to vaccinate their children against influenza next year if they plan to vaccinate themselves, meaning they trust the medical system and more specifically put faith in vaccines. Of interest, caregivers put more value and enhance the perceived risks associated with taking action, such as a child having a severe reaction to a vaccine, than the risk of an omitted action, like the chance of contracting a disease.15 It is important for primary care providers to highlight the safety and efficacy of the flu vaccines to parents.

Past behavior is a strong factor in vaccinating children and those having been vaccinated in the past against seasonal influenza being more likely to be vaccinated against pandemic influenza.16 In our study, the influenza vaccination status of a child last year was strongly associated with a caregiver's plan to vaccinate next year (P < .001). Similarly, in a study from England, among 1001 parents with one-half their children vaccinated to influenza, vaccine uptake was associated with the child having previously vaccinated against influenza.17

Understanding factors that influence a change in influenza vaccine behaviour from year-to-year may guide public health efforts to increase uptake. Fogel and Hicks recently coined the term “flu-floppers,” describing patients who received the influenza vaccine in some years but not others. They suggested that many appear to randomly alternate vaccination status from year to year.18 In a year of COVID-19 pandemic, it is likely that public health worries influence parents to plan on vaccinating their children and only 4% of children vaccinated last year are likely not to be vaccinated next year (38/930 families) compared with 28.6% (417/1460) “flipping” toward vaccinating. Those who stop yearly influenza vaccinations for their children most commonly cited a perceived lack of effectiveness of the vaccine (29%, n = 41).18 Public health officials will need to ensure clear messaging on the safety of influenza vaccines next year, especially in face of COVID-19, to influence parental decision making to convert into vaccinating children.

In a web-based survey of 500 parents from an online panel representative of the US population, the main drivers of parents' decision to vaccinate their child against influenza were prevention of influenza, reduction of influenza symptoms, and doctor recommendation; barriers to vaccination included the risk of adverse effects and the perceived low risk of influenza.19 Similarly, a review of 64 studies reported an association between vaccination uptake and perceived vaccine safety, general positive attitudes toward vaccination, positive vaccine recommendations, social influences and trust in the healthcare profession, and perceiving fewer practical difficulties with vaccination.20 We similarly found that caregivers vaccinating their children according to the schedule, and thus likely have trust in the idea of vaccination, are likely to accept the influenza vaccination for their child next year.

Level of caregiver concern that the child had COVID-19 was associated with the change in action towards planning to vaccinate children against influenza. In a systematic review of 37 studies involving the 2009 influenza A virus subtype H1N1 (A/H1N1) pandemic influenza outbreak, the degree of threat experienced and perceptions of vaccination as an effective coping strategy was associated with stronger intentions and greater uptake of vaccination and concern about the disease as well as believing oneself to be at risk to H1N1 influenza were important factors.16 Fear of the child being sick with COVID-19 is a significant predictor of caregivers changing their mind to start vaccinating next year, which is supported by the fact that correlations were found between online searches for influenza vaccines and COVID-19, especially in “hotspots” of COVID-19, and increased interest in influenza vaccine compared with similar time periods in non-pandemic years.11

Although caregivers with greater than high school education are more likely to vaccinate their children against influenza (79% vs 71.4%, P < .01), including those not vaccinating last year (78.5% vs 71.4%, P = .005), when other factors were assessed in the multivariate analysis, greater education was associated with lower likelihood of families changing their mind to start vaccinating (OR 0.71, 95% CI 0.52-0.96; P = .028). Level of parental education is associated with both high and low uptake of vaccines,21 likely due to education serving as a surrogate marker for other factors impacting adherence.

Our study has a number of limitations. First, the population of caregivers responding to the survey does not represent all parents in the sites where the study was conducted, as we administered the survey in a pediatric ED setting and only a subset of families (likely <5% of visitors to 17 the pediatric EDs) filled out the survey. We also relied on caregiver possession of a smartphone/tablet/computer to complete the survey online, which may have limited a small percentage of caregivers from responding. Second, we relied on the accuracy of caregiver responses to the status of both influenza and non-influenza vaccinations, because no patient records were checked for confirmation. Finally, as in any survey, caregivers may share their opinions about vaccinations, but act differently once cities are back to a more normal activity, which highlights the importance of public health measures to encourage and ensure adequate vaccination uptake.

In summary, we report propensity of caregivers to vaccinate their children against influenza at a higher rate in the next influenza season, with 29% of those that did not vaccinate last year reporting a plan to do so next year. Caregivers who plan to vaccinate themselves, who received influenza vaccine last year, who were worried their child had COVID-19, and whose children had up-to-date vaccinations other than influenza were associated with plan to vaccinate against influenza. The SAR-CoV-2 pandemic is an opportunity to ramp up influenza vaccination for families previously choosing not to vaccinate. Providers should proactively reach out to offer influenza vaccination, especially to families who have not vaccinated in the past as part of a campaign to increase protection from influenza and mitigate morbidity and mortality during the overlapping influenza epidemic and COVID-19 pandemic.

Data Statement

Data sharing statement available at www.jpeds.com.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Simon Craig, Dr Arjun Rao, Dr Esther L. Yue, Dr Ayano Shinagawa, Dr Kayo Yoshimura, Dr Christopher Kelly, and Dr Mike A. Irvine for their help with this study. We also thank Marissa Gibbard, Dawn Mount, and Halleu Cote from the BC Children's Research Institute for their remarkable support of conducting this study in the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

International COVID-19 Parental Attitude Study (COVIPAS) Group:

Sarah Ahmed, Samina Ali, Julie C. Brown, Simon Craig, Adrienne L. Davis, Nathalie Gaucher, Gualco Gianluca, Ran Goldman, Mark Griffiths, Jeanine E. Hall, Matt Hansen, Thomas L. Hurt, Christopher Kelly, Eileen J. Klein, Eran Kozer, Shashidhar Marneni, Ahmed Mater, Rakesh Mistry, Cristina Parra, Naveen Poonai, Arjun Rao, David Sheridan, Naoki Shimizu, and Esther L. Yue

Supplementary Data

Appendix

List of additional members of the International COVID-19 Parental Attitude Study (COVIPAS) Group Information (alphabetical):

Dr Sarah Ahmed, MD, Ta Department of Emergency Medicine, Mary Bridge Children's Hospital, Tacoma, WA.

Dr Samina Ali, MDCM, FRCPC, Department of Pediatrics, Faculty of Medicine & Dentistry, Women and Children's Health Research Institute, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada.

Dr Julie C. Brown, MD, Seattle Children's Hospital and University of Washington School of Medicine, Seattle, WA.

Dr Simon Craig, MBBS, FACEM, MPE, MPH, School of Clinical Sciences, Monash University, Melbourne, Australia.

Dr Adrienne L. Davis, MD, MSc, Pediatric Emergency Medicine, Hospital for Sick Children and University of Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

Dr Nathalie Gaucher, MD, FRCPC, PhD, Division of Emergency Medicine, Department of Pediatrics, CHU Sainte-Justine, Université de Montréal, Montréal, Québec, Canada.

Dr Gualco Gianluca, MD, Pediatric Emergency Department, Pediatric Institute of Italian part of Switzerland, Ticino, Switzerland.

Dr Ran Goldman, MD, The Pediatric Research in Emergency Therapeutics (PRETx) Program, Division of Emergency Medicine, Department of Pediatrics, University of British Columbia, and BC Children's Hospital Research Institute, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada.

Dr Mark Griffiths, MD, Division of Pediatric Emergency Medicine, Children's Healthcare of Atlanta, Emory School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA.

Dr Jeanine E. Hall, MD, Division of Emergency and Transport Medicine, Children's Hospital Los Angeles, USC Keck School of Medicine, Los Angeles, CA.

Dr Matt Hansen, MD, MCR, Department of Emergency Medicine, Oregon Health and Sciences University, Portland, OR.

Dr Thomas L. Hurt, MD, MED, Department of Emergency Medicine, Mary Bridge Children's Hospital, Tacoma, WA.

Dr Christopher Kelly, MD, Department of Pediatric Emergency Medicine, New York Presbyterian Brooklyn Methodist Hospital, New York, NY.

Dr Eileen J. Klein, MD, MPH Seattle Children's Hospital and University of Washington School of Medicine, Seattle, WA.

Dr Eran Kozer, MD, Sackler Faculty of Medicine, Tel Aviv University, Be'er Yakov, Israel.

Dr Shashidhar Marneni, MD, Department of Pediatric Emergency Medicine, Children's Medical Center of Dallas, UT Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX.

Dr Ahmed Mater, MD, FRCPC, FAAP, Pediatric Emergency Medicine, Jim Pattison Children's Hospital, and University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, Canada.

Dr Rakesh Mistry, MD, MS, Department of Emergency Medicine, Children's Hospital Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, CO.

Dr Cristina Parra, PhD, Hospital Sant Joan de Déu Barcelona, Pediatric Emergency Department, Barcelona, Spain.

Dr Naveen Poonai, MD, FRCPC, Departments of Paediatrics, Internal Medicine, Epidemiology & Biostatistics, Schulich School of Medicine & Dentistry, Western University, and Children's Health Research Institute, London, Ontario, Canada.

Dr Arjun Rao, MD, Department of Pediatric Emergency Medicine, Sydney Children's Hospital, Sydney, Australia.

Dr David Sheridan, MD, MCR, Department of Emergency Medicine, Oregon Health and Sciences University, Portland, OR.

Dr Naoki Shimizu, MD, PhD, Department of Pediatrics, St. Marianna University School of Medicine, Tokyo, Japan.

Dr Esther L. Yue, MD, Department of Emergency Medicine, Oregon Health and Sciences University, Portland, OR.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . US Department of Health & human Services; Washington, DC: 2020. Estimated influenza illnesses, medical visits, hospitalizations, and deaths in the United States—2018-2019 influenza season [Internet]https://www.cdc.gov/flu/about/burden/2018-2019.html Accessed August 18, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . US Department of Health & human Services; Washington, DC: 2019. Flu vaccine coverage, United States 2018-19 influenza season [Internet]https://www.cdc.gov/flu/fluvaxview/coverage-1819estimates.htm Accessed August 18, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Singer B. COVID-19 and the next influenza season. Sci Adv. 2020;6:eabd0086. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abd0086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thanh Le T., Andreadakis Z., Kumar A., Romàn R., Tollefsen S., Saville M. The COVID-19 vaccine development landscape. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2020;19:305–306. doi: 10.1038/d41573-020-00073-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Broadfoot M. Scientific American; New York, NY: 2020. Coronavirus and the Flu: A Looming Double Threat [Internet] Sci Am 2020.https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/coronavirus-and-the-flu-a-looming-double-threat/ Accessed August 18, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kempe A., Saville A., Albertin C., Zimet G., Vreck A., Helmkamp L. Parental hesitancy about routine childhood and influenza vaccinations: a national survey. Pediatrics. 2020;146:e20193852. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-3852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gostin L.O., Salmon D.A. The dual epidemics of COVID-19 and influenza: vaccine acceptance, coverage, and mandates. JAMA. 2020;324:335–336. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.10802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nowak M.D., Sordillo E.M., Gitman M.R., Mondolgi A.E. Co-infection in SARS-CoV-2 infected patients: where are influenza virus and rhinovirus/enterovirus? J Med Virol. 2020 doi: 10.1002/jmv.25953. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim D., Quinn J., Pinsky B., Shah N.H., Brown I. Rates of co-infection between SARS-CoV-2 and other respiratory pathogens. JAMA. 2020;323:2085–2086. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.6266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wu Xiaojing, Cai Ying, Huang Xu, Yu Xin, Zhao Li, Wang Fan. Co-infection with SARS-CoV-2 and influenza A virus in patient with pneumonia, China. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26:1326. doi: 10.3201/eid2606.200299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Paguio J.A., Yao J.S., Dee E.C. Silver lining of COVID-19: Heightened global interest in pneumococcal and influenza vaccines, an infodemiology study. Vaccine. 2020;38:5430–5435. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.06.069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schmid P., Rauber D., Betsch C., Lidolt G., Denker M.-L. Barriers of influenza vaccination intention and behavior—a systematic review of influenza vaccine hesitancy, 2005-2016. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0170550. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0170550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dubé E., Gagnon D., MacDonald N., Bocquier A., Peretti-Watel P., Verger P. Underlying factors impacting vaccine hesitancy in high income countries: a review of qualitative studies. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2018;17:989–1004. doi: 10.1080/14760584.2018.1541406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Damnjanović K., Graeber J., Ilić S., Lam W.Y., Lep Ž., Morales S. Parental decision-making on childhood vaccination. Front Psychol. 2018;9:735. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Damnjanović K., Ilić S., Pavlović I., Novković V. Refinement of outcome bias measurement in the parental decision-making context. Eur J Psychol. 2019;15:41–58. doi: 10.5964/ejop.v15i1.1698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bish A., Yardley L., Nicoll A., Michie S. Factors associated with uptake of vaccination against pandemic influenza: a systematic review. Vaccine. 2011;29:6472–6484. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.06.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smith L.E., Webster R.K., Weinman J., Amlôt R., Yiend J., Rubin G.J. Psychological factors associated with uptake of the childhood influenza vaccine and perception of post-vaccination side-effects: a cross-sectional survey in England. Vaccine. 2017;35:1936–1945. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hicks BNF Steven D. “Flu-floppers”: factors influencing families' fickle flu vaccination patterns. Clinic Pediatr. 2020;59:352–359. doi: 10.1177/0009922819901002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Flood E.M., Rousculp M.D., Ryan K.J., Beusterien K.M., Divino V.M., Toback S.L. Parents' decision-making regarding vaccinating their children against influenza: a web-based survey. Clin Ther. 2010;32:1448–1467. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2010.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smith L.E., Amlôt R., Weinman J., Yiend J., Rubin G.J. A systematic review of factors affecting vaccine uptake in young children. Vaccine. 2017;35:6059–6069. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.09.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Larson H.J., Jarrett C., Eckersberger E., Smith D.M.D., Paterson P. Understanding vaccine hesitancy around vaccines and vaccination from a global perspective: a systematic review of published literature, 2007-2012. Vaccine. 2014;32:2150–2159. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.01.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.