Abstract

Purpose

Whether or not young patients with squamous cell carcinoma of oral cavity (OC-SCC) have a difference in prognosis remains a controversy. This study aimed to analyze the clinical characteristics and difference of survival rates between adult patients less than 40 years of age and those 40 years of age and older.

Methods

A retrospective analysis was conducted using the database of patients diagnosed with OC-SCC between 1990 and 2013 in the Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center, but patients older than 85 years, younger than 18 years, or died within 6 months of diagnosis were excluded. Patients were categorized into two groups: the young group (< 40 years of age) and the older group (≥ 40 years of age). Cox regression, survival and subgroups analyses were performed. The primary endpoints included the rates of 5-year overall survival (OS) and disease-specific survival (DSS).

Results

A total of 1902 OC-SCC patients were identified. The percentage of female in the young group was significantly higher than that in the older group (40.27% vs 31.03%, p < 0.001). This study failed to find the difference in TNM classification or tumor stage between the two groups (p > 0.05). The young group was more likely to receive adjuvant radiotherapy and/or chemotherapy (42.48% vs 26.91%, p < 0.001). The 5-year OS rate (71% vs. 57%, p < 0.001) and DSS rate (72% vs 58%, p < 0.001) in patients under 40 years were significantly higher than those for the older group.

Conclusion

Our findings suggested that OC-SCC in younger patients did not present at a more advanced stage. In addition, young age is an independent predictor for better survival.

Keywords: Young, Squamous cell carcinoma, Oral cavity, Survival

Introduction

Oral cavity cancer (OCC), which anatomically involves the lips, the front two-thirds of the tongue, the gums, the lining inside the cheeks and lips, the floor (bottom) of the mouth under the tongue, the hard palate (bony top of the mouth), and the small area of the gum behind the wisdom teeth [1], is one of the most common subsites of head and neck cancer [2]. Over 90% of cases are squamous cell carcinomas (SCC) [2]. Alcohol and tobacco consumption are considered to be the main risk factors for OCC [4, 5]. Further, OCC was found to be closely related to a high-risk human papillomavirus (HPV) infection [6]. In many parts of Asia, betel quid chewing increases the risk of oral cancer, independently of tobacco and alcohol use [7]. Worldwide, it is estimated that there will be 354,864 new cases of oral cancer and an estimated 177,384 people will die of the disease in 2018, representing close to 2% of cancer deaths. The incidence and mortality rates in men are approximately two times higher than those in women. Notably, OCC tends to cluster in South Asia [7]. In the United States, the incidence rate is highest in individuals aged 55–64 years, with a median age of 63 years. Data estimates from the US for the years 2009–2015 showed that the number of surviving patients of oral cavity and pharynx cancer at 5 years is 65.3%. Most patients (93.4%) are diagnosed at age 45 and above [9]. Traditionally, OCC occurs in the elderly during the 5th through the 7th decades of life; however, it has been reported to be increasing in incidence among younger populations globally, especially in young women [11].

The cause of this increasing trend remains unclear, but we should draw attention to the younger patients. Many published reports have obtained conflicting results. Some studies report that OC-SCC in young patients is more aggressive. Conversely, other studies suggest that younger patients with OC-SCC did not have worse survival. Whether or not the young with OC-SCC have a difference in prognosis remains a controversy. In this single-institution study performed in southern China, we aimed to compare differences in survival between patients aged younger than 40 years and those who were 40 years and older.

Materials and methods

The study was conducted in Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center (SYSUCC). The medical files, containing a total of 1902 patients who were treated primarily by surgical resection and histologically confirmed in our center from 1990 to 2013, were retrospectively reviewed. All the patients were followed for a minimum of 5 years. Patients were divided into two groups depending on age (patients < 40 years and patients ≥ 40 years). Demographics (age and sex), year of diagnosis (1990–1999, 2000–2009, 2010–2013), habits (alcohol and tobacco use), TNM classification, tumor stage (followed the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, Seventh Edition), treatment (surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy), and survival outcomes were documented (see Table 1), and these factors were compared between patients younger than 40 years and the older patients. P < 0.01 was considered to be statistically significant. For statistical analyses, we used SPSS, version 16.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| All patients | Young group (< 40) | Older group (40–85) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | p value |

| Total | 1902 | 100 | 226 | 100 | 1676 | 100 | |

| Age: median ± SD | 54.6 ± 12.2 | 33.5 ± 4.7 | 57.5 ± 9.9 | ||||

| Sex | < 0.001 | ||||||

| Male | 1291 | 67.88 | 135 | 59.73 | 1156 | 68.97 | |

| Female | 611 | 32.12 | 91 | 40.27 | 520 | 31.03 | |

| Period of diagnosis | 0.0520 | ||||||

| 1990–1999 | 627 | 32.97 | 88 | 38.94 | 539 | 32.16 | |

| 2000–2009 | 838 | 44.06 | 98 | 43.36 | 740 | 44.15 | |

| 2010–2013 | 437 | 22.98 | 40 | 17.70 | 397 | 23.69 | |

| Site | < 0.001 | ||||||

| Tongue | 1218 | 64.04 | 198 | 87.61 | 1020 | 60.83 | |

| Other parts of mouth | 635 | 33.39 | 26 | 11.50 | 609 | 36.34 | |

| Lip | 49 | 2.58 | 2 | 0.88 | 47 | 2.8 | |

| Smoking history | 0.0352 | ||||||

| Smoker | 767 | 40.33 | 102 | 45.13 | 665 | 39.68 | |

| Never | 807 | 42.43 | 78 | 34.51 | 729 | 43.50 | |

| Unknown | 328 | 17.25 | 46 | 20.35 | 282 | 16.83 | |

| Alcohol use history | 0.056 | ||||||

| Drinker | 1120 | 58.89 | 142 | 62.83 | 978 | 58.36 | |

| Never | 407 | 21.40 | 27 | 11.95 | 380 | 22.67 | |

| Unknown | 375 | 19.72 | 57 | 25.22 | 318 | 18.97 | |

| T classification | 0.3065 | ||||||

| T1 | 548 | 28.81 | 74 | 32.74 | 474 | 28.28 | |

| T2 | 731 | 38.43 | 77 | 34.07 | 654 | 39.02 | |

| T3 | 198 | 10.41 | 19 | 8.41 | 179 | 10.68 | |

| T4 | 411 | 21.61 | 55 | 24.34 | 356 | 21.24 | |

| Unknown | 14 | 1 | 0.44 | 13 | 0.78 | ||

| N classification | 0.6639 | ||||||

| N0 | 1249 | 65.67 | 150 | 66.37 | 1099 | 65.57 | |

| N1–3 | 547 | 28.76 | 61 | 26.99 | 486 | 29 | |

| Unknown | 106 | 5.57 | 15 | 6.64 | 91 | 5.43 | |

| Distant metastases invasion | 0.8439 | ||||||

| M0 | 1895 | 99.63 | 225 | 99.56 | 1670 | 99.64 | |

| M1 | 7 | 0.37 | 1 | 0.44 | 6 | 0.36 | |

| Tumor stage extension | 0.6774 | ||||||

| Stage I–II | 964 | 50.68 | 117 | 51.77 | 847 | 50.54 | |

| Stage III–IV | 823 | 43.27 | 93 | 41.15 | 730 | 43.56 | |

| Unknown | 115 | 6.05 | 16 | 7.08 | 99 | 5.91 | |

| Treatment | |||||||

| Surgery only | 1028 | 54.05 | 94 | 41.59 | 934 | 55.73 | < 0.001 |

| Surgery with RT/CT | 547 | 28.76 | 96 | 42.48 | 451 | 26.91 | < 0.001 |

| RT/CT | 327 | 17.19 | 36 | 15.93 | 291 | 17.36 | 0.1153 |

Bivariate analysis of the independent variables was done using the Chi-square test to compare characteristics between the two groups. P value < 0.01 indicates a statistically significant difference. CT chemotherapy, RT radiotherapy

Results

A total of 1902 patients comprised the study cohort. Those who were older than 85 years, younger than 18 years, or died within 6 months of diagnosis were excluded. The clinicopathologic characteristics of the two groups are presented in Table 1. Among these patients, 226 (11.88%) were less than 40 years of age (young group). Overall, the average patient age was 54.6 ± 12.2 years and 33.5 ± 4.7 years in the young group and 57.5 ± 9.9 years in the older group. In the young group, the morbidity rate of females was significantly higher than that in the older group (40.27% vs. 31.03%). The tongue was the most common primary site (64.04%), followed by other parts of the mouth. The tongue SCC in young patients appeared to be more common than in the older group (87.61% vs. 60.83%, p < 0.001). No statistical differences were found between the two groups with regard to tobacco and/or alcohol use. There was no significant difference between the groups concerning TNM classification or tumor stage. Interestingly, compared with the older group, the young group was less likely to undergo surgery alone (94, 41.59% vs. 934, 55.73%, p < 0.001). Young patients tended to receive postoperative adjuvant radiotherapy (RT) and/or chemotherapy (CT) compared with the older group (96, 42.48% vs. 451, 26.91%, p < 0.001).

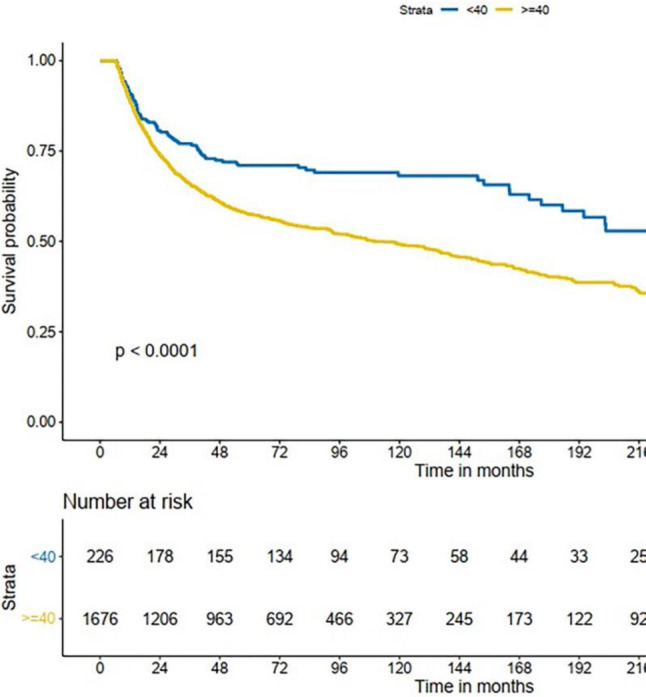

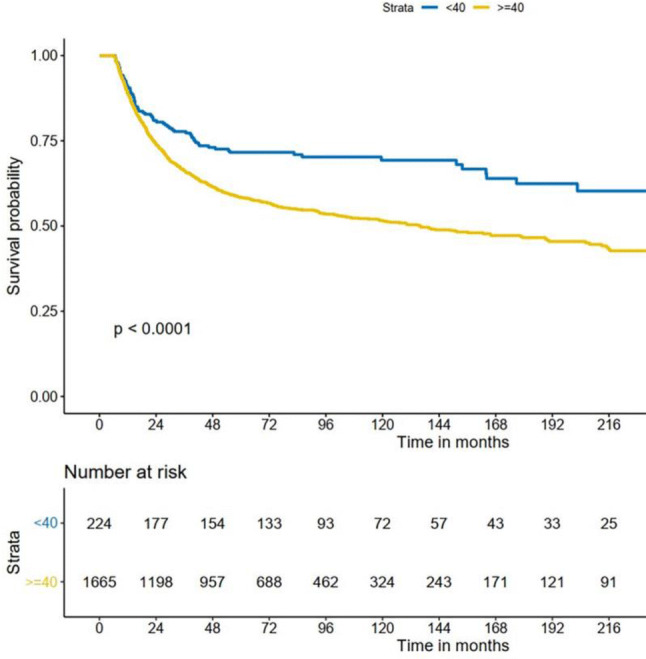

The minimum duration of follow-up time was 5 years. Of 1902 patients, the 5-year overall survival (OS) rate was 59% [95% confidence interval (CI) 56.8–61.2%] and the 5-year disease-specific survival (DSS) rate was 60% (95% CI 57.8–62.2%). The 5-year OS rate was 71% (95% CI 68.0–77.0%) in the young group and 57% (95% CI 54.6–59.4%) in the older group. The 5-year DSS rate was 72% (95% CI 67.0–78.0%) in the young group and 58% (95% CI 55.6–60.4%) in the older group. The OS and DSS between the two groups were compared with Kaplan–Meier plot. The results indicated that there were significant differences between the two groups. Figures 1 and 2 show that both OS and DSS in younger patients with OC-SCC are better than in older patients.

Fig. 1.

Kaplan–Meier estimate of overall survival between the age groups

Fig. 2.

Kaplan–Meier estimate of disease-specific survival between the age groups

The univariate and multivariable Cox proportional hazards model for DSS were performed (Table 2). Older age was a significant predictor of worse prognosis at all stages. In addition, other clinically significant worse predictors of DSS in both univariate and multivariable regression included male sex, tumor site (other part of mouth), higher TNM classification, worse tumor stage, and treatment with RT/CT.

Table 2.

Univariate and multivariate analyses of clinicopathologic and treatment factors for DSS

| Univariate | Multivariate | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | p | HR (95% CI) | p | |

| Age | ||||

| Young group (ref) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Older group | 1.685 (1.321–2.149) | < 0.001 | 1.593 (1.240–2.047) | < 0.001 |

| Sex | ||||

| Male(ref) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Female | 0.695 (0.596–0.809) | < 0.001 | 0.910 (0.758–1.093) | 0.3130 |

| Period | ||||

| 1990–1999 (ref) | 1 | 1 | ||

| 2000–2009 | 0.856 (0.737–0.994) | 0.0420 | 0.852 (0.710–1.023) | 0.0857 |

| 2010–2013 | 0.667 (0.546–0.813) | < 0.001 | 0.694 (0.56–0.861) | < 0.001 |

| Site | ||||

| Tongue (ref) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Other site of OC | 1.855 (1.618–2.126) | < 0.001 | 1.389 (1.202–1.604) | < 0.001 |

| Lip | 0.447 (0.239–0.836) | 0.0117 | 0.470 (0.249–0.888) | 0.0201 |

| Smoking history | ||||

| Smoker (ref) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Never | 1.349 (1.166–1.561) | < 0.0001 | 0.992 (0.817–1.203) | 0.9311 |

| Unknown | 0.898 ( 0.726–1.111) | 0.3211 | 0.951 (0.620–1.458) | 0.8172 |

| Alcohol use history | ||||

| Drinker (ref) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Never | 1.365 (1.164–1.602) | 0.0001 | 1.097 (0.906–1.328) | 0.3443 |

| Unknown | 0.869 (0.719–1.050) | 0.1457 | 0.870 (0.587–1.290) | 0.4899 |

| T classification | ||||

| T1(ref) | 1 | 1 | ||

| T2 | 1.800 (1.482–2.187) | < 0.001 | 1.454 (1.191–1.775) | < 0.001 |

| T3 | 2.840 (2.225–3.625) | < 0.001 | 1.540 (1.133–2.094) | < 0.001 |

| T4 | 3.590 (2.942–4.380) | < 0.001 | 1.727 (1.313–2.271) | < 0.001 |

| Unknown | 1.488 (0.658–3.365) | 0.3399 | 1.065 (0.253–4.489) | 0.9315 |

| N classification | ||||

| N0 (ref) | 1 | 1 | ||

| N1-3 | 2.480 (2.149–2.861) | < 0.001 | 1.684 (1.350–2.102) | < 0.001 |

| Unknown | 2.548 (1.988–3.265) | < 0.001 | 0.985 (0.180–5.391) | 0.9865 |

| Distant metastases | ||||

| M0 (ref) | 1 | 1 | ||

| M1 | 5.704 (2.706–12.021) | < 0.0001 | 3.118 (1.453–6.688) | 0.0035 |

| Tumor stage | ||||

| Stage I–II (ref) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Stage III–IV | 2.613 (2.258–3.023) | < 0.001 | 2.425 (2.111–2.785) | < 0.001 |

| Unknown | 2.827 (2.198–3.634) | < 0.001 | 1.061 (0.187–6.017) | 0.9466 |

| Treatment | ||||

| Surgery only (ref) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Surgery with RT/CT | 1.698 (1.443–1.999) | < 0.001 | 1.297 (1.088–1.546) | < 0.001 |

| RT/CT | 4.606 (3.904–5.435) | < 0.001 | 3.156 (2.605–3.824) | < 0.001 |

A Cox proportional hazards model was used to analyze predictors of survival. P value < 0.01 indicates a statistically significant difference

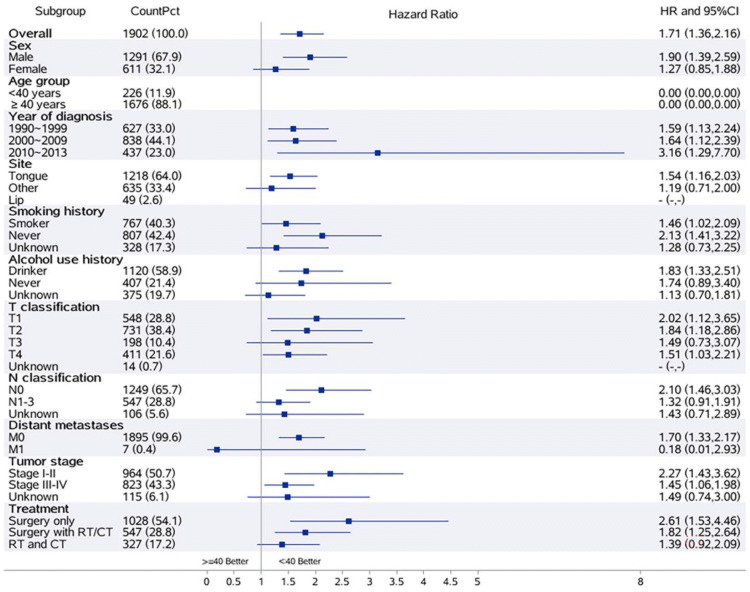

The DSS in the young group was consistently favorable [all hazard ratios (HR) except distant metastases M1] across all subgroups (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Subgroup analyses

Discussion

In many types of cancer, age at diagnosis is viewed as an independent predictor of outcome [11]. In the field of OC-SCC, there is no uniform category of “young” patients and previous analyses were performed using age thresholds ranging from 30 to 45 years of age [12–19]. It is difficult to determine a reasonable cutoff between “young” and “old” adults. Because 40 years of age was used as an age threshold in most of the previous studies, it is reasonable that for our study, a young adult is defined as someone less than 40 years of age. The inconsistent cutoff age for young patients has contributed to the conflicting findings in the literature. Therefore, there is a need for studies to use a standard division.

A review of the reported studies demonstrates that our clinical characteristic findings are in agreement with several previously published large cohort studies [12–19]. First, OC-SCC mainly occurs in men between the 5th and 6th decades of life. Second, the young group exhibited a higher proportion of women compared with adults 40 years and older (40.27% vs. 31.03%, respectively). The findings should heighten the awareness of the occurrence of OC-SCC in young women and merits further investigation. Third, lymph node (28.76%) and distant (0.37%) metastases are not unusual and a majority of patients had early stage disease (Stage I–II, 50.68%). Furthermore, more than half of patients (54.05%) were treated with surgery alone, as surgical treatment is the main treatment method. In the young group, patients were more likely to receive adjuvant RT and/or CT (42.48% vs. 26.91%, p < 0.01). In the findings on site predilection was generally consistent with the previous OC-SCC literature [3, 22, 23]. The young group was more likely to have tongue cancer (87.61% vs. 60.83%, p < 0.01).

Several similar studies have analyzed survival of patients with early-onset OC-SCC (Table 3). More population-based studies with large samples are needed, especially performed in non-western regions to estimate the outcome of OC-SCC in young groups of patients. In this study, it is notable that 11.88% of patients were diagnosed before age of 40 years, a higher rate than that in most studies, particularly those studies from the US and Europe [20, 24–26]. Considering that cancers of the oral cavity are highly frequent in southern Asia, the higher proportion in young people might indicate that the sociocultural lifestyle of the population, such as betel quid chewing and the use of tobacco and alcohol, plays an important role in this geographic or regional diversity [27]. In our study, the percentage of patients with early stage (Stage I–II, 50.68%) was lower than in western developed countries [20], but higher than other southern Asian regions (e.g., India, Thailand, Taiwan, and Japan) [11, 14, 17, 19, 28–30]. It is suggested that low socioeconomic status or related patient factors (e.g., education, diet, health care, and living conditions) may increase the risk of OC-SCC. A significant difference in survival rates was found among young people between affluent and non-affluent groups [31]. A deeper knowledge of the public on OC-SCC could help avoid exposing people to the risk factors. This means we need to do more to raise awareness by identifying people at risk and taking measures to allow early detection and minimize the undesirable consequences of OC-SCC [32].

Table 3.

Similar studies that used a cutoff age of 40

| Author | Year | Patients | Young group | Male:Female in young | Survival | Prognosis for young group | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Young | Old | ||||||

| Udeabor et al. [26] | 2012 | 977 | 3.9% | 3.8:1 | 66.2%/5-y OS | 57.6%/5-y OS | Better |

| Van Monsjou et al. [25] | 2013 | 1762 | 3.1% | 1.8:1 |

58%/5-y OS 69%/5-y DSS |

42%/5-y OS 74%/5-y DSS |

No significant difference in DSS; better for OS |

| Fang et al. [43] | 2014 | 176 | 8.5% | 0.7:1 | 63%5-y DSS | 625-y DSS | No significant difference |

| Sun Q [15] | 2015 | 486 | 7.2% | 1.6:1 | 65%5-y DSS | 66.75-y DSS | No significant difference |

| Jae-Ho Jeon et al. [37] | 2016 | 117 | 20% | 1.9:1 |

40%/5-y OS 42%/5-y DSS |

70%/5-y OS 73%/5-y DSS |

Worse |

| Mahmood et al. [11] | 2018 | 115 | 34.8% | 4.7:1 | 62.5%/5-y OS | 37.3%/5-y OS | Better |

| Oliver et al. [20] | 2019 | 22 930 | 9.9% | 1.15:1 | 79.6%/5-y OS | 69.5%/5-y OS | Better |

Historically, numerous previous reports on this topic found that the biologic behavior of OC-SCC in younger patients was more aggressive compared with that in elderly patients [13, 34]. It has been reported that OC-SCC in young patients had a significantly higher rate of nodal metastases, which resulted in a more advanced tumor stage [20, 34, 35]. In clinicopathologic features, some studies have shown OC-SCC in young patients had a more advanced TNM classification and higher proportion of poorly differentiated tumors [36, 37]. However, reviewing the most recent studies, the treatment outcomes of the young group are heterogeneous and it is possible to confirm that younger patients may have similar or better outcomes than older patients [18, 20, 26, 38–44]. In our cohort, histopathologic variables, such as tumor TNM, did not show any significant differences between young and old patients. And, it was not possible to confirm a higher rate of nodal metastases. Therefore, it was no surprise that no difference was found in tumor stage between the two groups (p = 0.677). Interestingly, treatment comparisons showed that the younger patients were more likely to receive postoperative adjuvant RT and/or CT, a more aggressive approach than older patients. RT, generally recommended as an adjuvant treatment in head and neck cancers, is preferred for those with evidence of adverse features or advanced stage. For the patients involved in our study, CT alone is not recommended as a postoperative adjuvant therapy without RT. However, in rare cases, personal reasons, for example, misconceptions in irradiation, economic problem and rejection of so many times of radiotherapy fractions, could explain that they underwent CT alone as an adjuvant therapy without RT. It is unclear why young patients undergo intensification. A possible reason is that the young patients were more tolerant to adjuvant therapy than the old group and practitioners probably think young patients could benefit from treatment intensification despite there being no clear indication for adjuvant therapy.

The 5-year OS was 59% and the 5-year DSS rate was 60%. The 5-year OS was 71% in the young group and 57% in the older group. The 5-year DSS was 72% in the young group and 58% in the older group. The higher OS and DSS in young patients showed a significant prognostic advantage in younger patients. In both univariate and multivariable analyses, older age, advanced TNM stage, surgery with RT and/or CT, and RT and/or CT were associated with worse prognosis. In DSS subgroup analyses, the results of the better survival of the young group, as compared with the older group, were that treatment outcome was consistently favorable across all patient subgroups (except distant metastases M1). In clinical practice, age, stage, and site are the most important determinants of treatment selection for patients with OC-SCC [45]. However, these outcome data of the present study suggest that young age alone should not alter treatment.

There are limitations to our study. First, it was conducted at a single institution. Another limitation is lack of matched controls and recurrence or clinicopathologic data (e.g., tumor grade, extracapsular extension, margins, and number of examined lymph nodes). However, despite these limitations, our study is one of the largest studies from a high-risk region of OC-SCC, including the high quality of the data, which enabled us to control for multiple factors and minimize error and bias.

Conclusion

OC-SCC in young adults represents a rare disease, with an increasing incidence, particularly in females. Comparison by age group showed no differences in rates of advanced TNM stage. But young adults are more commonly treated with adjuvant RT and/or CT. Our findings have evidenced that young age at diagnosis is an independent predictor of better survival. Thus, a comprehensive tailoring of treatment on a case-by-case basis according to current guidelines is recommended.

Funding

Research grants from funding agencies (the National Natural Science Foundation of China, No. 81802713 and No. 81672671).

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center ethics committee (GZR2018-188) and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Shuwei Chen and Zhu Lin contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Shuwei Chen, Email: chenshuw@sysucc.org.cn.

Zhu Lin, Email: linzhu@sysucc.org.cn.

Jingtao Chen, Email: chenjt1@sysucc.org.cn.

Ankui Yang, Email: yangak@sysucc.org.cn.

Quan Zhang, Email: zhangquan@sysucc.org.cn.

Chuanbo Xie, Email: xiechb@sysucc.org.cn.

Xing Zhang, Email: zhangx1@sysucc.org.cn.

Zhongyuan Yang, Email: yangzhy@sysucc.org.cn.

Wenkuan Chen, Email: chenwk@sysucc.org.cn.

Ming Song, Email: songming@sysucc.org.cn.

References

- 1.Rodríguez-Santamarta T, Rodrigo JP, García-Pedrero JM, et al. Prevalence of human papillomavirus in oral squamous cell carcinomas in northern Spain. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2016;273(12):4549–4559. doi: 10.1007/s00405-016-4152-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.de Castro JG, Dos SA, Aparecida DAKF, et al. Tongue cancer in the young[J] Curr Opin Oncol. 2016;28(3):193–194. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0000000000000285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chi AC, Day TA, Neville BW. Oral cavity and oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma–an update[J] CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65(5):401–421. doi: 10.3322/caac.21293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sankaranarayanan R, Ramadas K, Thara S, et al. Long term effect of visual screening on oral cancer incidence and mortality in a randomized trial in Kerala, India[J] Oral Oncol. 2013;49(4):314–321. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2012.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chaturvedi P, Singh A, Chien CY, et al. Tobacco related oral cancer[J] BMJ. 2019;365:l2142. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l2142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hubbers CU, Akgul B. HPV and cancer of the oral cavity[J] Virulence. 2015;6(3):244–248. doi: 10.1080/21505594.2014.999570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guha N, Warnakulasuriya S, Vlaanderen J, et al. Betel quid chewing and the risk of oral and oropharyngeal cancers: a meta-analysis with implications for cancer control[J] Int J Cancer. 2014;135(6):1433–1443. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, et al. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries[J] CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(6):394–424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.SEER Cancer Stat Facts: oral cavity and pharynx cancer. National Cancer Institute. Bethesda, MD, https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/oralcav.html.

- 10.Patel SC, Carpenter WR, Tyree S, et al. Increasing incidence of oral tongue squamous cell carcinoma in young white women, age 18 to 44 years[J] J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(11):1488–1494. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.31.7883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mahmood N, Hanif M, Ahmed A, et al. Impact of age at diagnosis on clinicopathological outcomes of oral squamous cell carcinoma patients[J] Pak J Med Sci. 2018;34(3):595–599. doi: 10.12669/pjms.343.14086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garavello W, Spreafico R, Gaini RM. Oral tongue cancer in young patients: a matched analysis[J] Oral Oncol. 2007;43(9):894–897. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2006.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Soudry E, Preis M, Hod R, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma of the oral tongue in patients younger than 30 years: clinicopathologic features and outcome[J] Clin Otolaryngol. 2010;35(4):307–312. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-4486.2010.02164.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Komolmalai N, Chuachamsai S, Tantiwipawin S, et al. Ten-year analysis of oral cancer focusing on young people in northern Thailand[J] J Oral Sci. 2015;57(4):327–334. doi: 10.2334/josnusd.57.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sun Q, Fang Q, Guo S. A comparison of oral squamous cell carcinoma between young and old patients in a single medical center in China[J] Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8(8):12418–12423. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cariati P, Cabello-Serrano A, Perez-De PM, et al. Oral and oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma in young adults: a retrospective study in Granada University Hospital[J] Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2017;22(6):e679–e685. doi: 10.4317/medoral.21755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Iamaroon A, Pattanaporn K, Pongsiriwet S, et al. Analysis of 587 cases of oral squamous cell carcinoma in northern Thailand with a focus on young people[J] Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2004;33(1):84–88. doi: 10.1054/ijom.2003.0503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Macek MD. Younger adults with oral cavity squamous cell cancer have a significantly higher 5-year survival rate than do older adults in the united states, controlling for patient- and disease-specific characteristics[J] J Evid Based Dent Pract. 2010;10(3):158–159. doi: 10.1016/j.jebdp.2010.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Iype EM, Pandey M, Mathew A, et al. Oral cancer among patients under the age of 35 years[J] J Postgrad Med. 2001;47(3):171–176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oliver JR, Wu SP, Chang CM, et al. Survival of oral tongue squamous cell carcinoma in young adults[J] Head Neck. 2019;41(9):2960–2968. doi: 10.1002/hed.25772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gamez ME, Kraus R, Hinni ML, et al. Treatment outcomes of squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity in young adults[J] Oral Oncol. 2018;87:43–48. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2018.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Manuel S, Raghavan SK, Pandey M, et al. Survival in patients under 45 years with squamous cell carcinoma of the oral tongue[J] Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003;32(2):167–173. doi: 10.1054/ijom.2002.0271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ibayashi H, Pham TM, Fujino Y, et al. Estimation of premature mortality from oral cancer in Japan, 1995 and 2005[J] Cancer Epidemiol. 2011;35(4):342–344. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2011.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pabiszczak MS, Wasniewska E, Mielcarek-Kuchta D, et al. Variable course of progression of oral cavity and oropharyngeal carcinoma in young adults[J] Contemp Oncol (Pozn) 2013;17(3):286–290. doi: 10.5114/wo.2013.35279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van Monsjou HS, Lopez-Yurda MI, Hauptmann M, et al. Oral and oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma in young patients: the Netherlands Cancer Institute experience[J] Head Neck. 2013;35(1):94–102. doi: 10.1002/hed.22935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Udeabor SE, Rana M, Wegener G, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity and the oropharynx in patients less than 40 years of age: a 20-year analysis[J] Head Neck Oncol. 2012;4:28. doi: 10.1186/1758-3284-4-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Krishna RS, Mejia G, Roberts-Thomson K, et al. Epidemiology of oral cancer in Asia in the past decade: an update (2000–2012) [J] Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2013;14(10):5567–5577. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2013.14.10.5567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mathew IE, Pandey M, Mathew A, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue among young Indian adults[J] Neoplasia. 2001;3(4):273–277. doi: 10.1038/sj.neo.7900172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huang CC, Ou CY, Lee WT, et al. Life expectancy and expected years of life lost to oral cancer in Taiwan: a nation-wide analysis of 22,024 cases followed for 10 years[J] Oral Oncol. 2015;51(4):349–354. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2015.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yamamoto N, Sato K, Yamauchi T, et al. A 5-year activity report from the Oral Cancer Center, Tokyo Dental College[J] Bull Tokyo Dent Coll. 2013;54(4):265–273. doi: 10.2209/tdcpublication.54.265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Warnakulasuriya S, Mak V, Moller H. Oral cancer survival in young people in South East England[J] Oral Oncol. 2007;43(10):982–986. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2006.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.de Camargo CM, Voti L, Guerra-Yi M, et al. Oral cavity cancer in developed and in developing countries: population-based incidence[J] Head Neck. 2010;32(3):357–367. doi: 10.1002/hed.21193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liao CT, Wang HM, Hsieh LL, et al. Higher distant failure in young age tongue cancer patients[J] Oral Oncol. 2006;42(7):718–725. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2005.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Funk GF, Karnell LH, Robinson RA, et al. Presentation, treatment, and outcome of oral cavity cancer: a National Cancer Data Base report[J] Head Neck. 2002;24(2):165–180. doi: 10.1002/hed.10004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lacy PD, Piccirillo JF, Merritt MG, et al. Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: better to be young[J] Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2000;122(2):253–258. doi: 10.1016/S0194-5998(00)70249-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang YY, Wang DC, Su JZ, et al. Clinicopathological characteristics and outcomes of squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue in different age groups[J] Head Neck. 2017;39(11):2276–2282. doi: 10.1002/hed.24898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jeon JH, Kim MG, Park JY, et al. Analysis of the outcome of young age tongue squamous cell carcinoma[J] Maxillofac Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017;39(1):41. doi: 10.1186/s40902-017-0139-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hyam DM, Conway RC, Sathiyaseelan Y, et al. Tongue cancer: do patients younger than 40 do worse?[J] Aust Dent J. 2003;48(1):50–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.2003.tb00009.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Friedlander PL, Schantz SP, Shaha AR, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue in young patients: a matched-pair analysis[J] Head Neck. 1998;20(5):363–368. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0347(199808)20:5<363::aid-hed1>3.0.co;2-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pitman KT, Johnson JT, Wagner RL, et al. Cancer of the tongue in patients less than forty[J] Head Neck. 2000;22(3):297–302. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0347(200005)22:3<297::aid-hed14>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Davidson BJ, Root WA, Trock BJ. Age and survival from squamous cell carcinoma of the oral tongue. Head Neck. 2001;23(4):273–279. doi: 10.1002/hed.1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lee CC, Ho HC, Chen HL, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma of the oral tongue in young patients: a matched-pair analysis[J] Acta Otolaryngol. 2007;127(11):1214–1217. doi: 10.1080/00016480701230910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fan Y, Zheng L, Mao MH, et al. Survival analysis of oral squamous cell carcinoma in a subgroup of young patients[J] Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2014;15(20):8887–8891. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2014.15.20.8887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Goldenberg D, Brooksby C, Hollenbeak CS. Age as a determinant of outcomes for patients with oral cancer[J] Oral Oncol. 2009;45(8):e57–e61. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2009.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Goldenberg D, Mackley H, Koch W, et al. Age and stage as determinants of treatment for oral cavity and oropharyngeal cancers in the elderly[J] Oral Oncol. 2014;50(10):976–982. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2014.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]