Abstract

Stroke is an acute cerebro-vascular disease with high incidence and poor prognosis, most commonly ischemic in nature. In recent years, increasing attention has been paid to inflammatory reactions as symptoms of a stroke. However, the role of inflammation in stroke and its underlying mechanisms require exploration. In this study, we evaluated the inflammatory reactions induced by acute ischemia and found that pyroptosis occurred after acute ischemia both in vivo and in vitro, as determined by interleukin-1β, apoptosis-associated speck-like protein, and caspase-1. The early inflammation resulted in irreversible ischemic injury, indicating that it deserves thorough investigation. Meanwhile, acute ischemia decreased the Sirtuin 1 (Sirt1) protein levels, and increased the TRAF6 (TNF receptor associated factor 6) protein and reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels. In further exploration, both Sirt1 suppression and TRAF6 activation were found to contribute to this pyroptosis. Reduced Sirt1 levels were responsible for the production of ROS and increased TRAF6 protein levels after ischemic exposure. Moreover, N-acetyl-L-cysteine, an ROS scavenger, suppressed the TRAF6 accumulation induced by oxygen-glucose deprivation via suppression of ROS bursts. These phenomena indicate that Sirt1 is upstream of ROS, and ROS bursts result in increased TRAF6 levels. Further, the activation of Sirt1 during the period of ischemia reduced ischemia-induced injury after 72 h of reperfusion in mice with middle cerebral artery occlusion. In sum, these results indicate that pyroptosis-dependent machinery contributes to the neural injury during acute ischemia via the Sirt1-ROS-TRAF6 signaling pathway. We propose that inflammatory reactions occur soon after oxidative stress and are detrimental to neuronal survival; this provides a promising therapeutic target against ischemic injuries such as a stroke.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s12264-020-00489-4) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: ROS, Stroke, Pyroptosis, TRAF6, Sirt1

Introduction

Ischemic stroke is one of the main diseases with high mortality and disability worldwide [1]. The location and size of the cerebral ischemic region depend on the distribution of the occluded artery, after which metabolic and functional dysfunctions emerge [2]. Generally, two therapies are used to treat stroke: prompt blood restoration by thrombolysis and mechanical thrombectomy [3]. However, the effects of these treatments are modest [4]. Moreover, the loss of neuronal cells is the vital problem in stroke, making recovery difficult or even impossible at the late stage [5]. Therefore, novel neuro-protective strategies at the early stage with more positive effects deserve to be explored further.

Neuroinflammation is reported to be induced by cerebral ischemia; this is initiated by the accumulation of inflammatory cells and mediators in the ischemic region from resident cerebral cells and infiltrating immune cells. Then, the following inflammatory injuries appear [6]. Recently, pyroptosis, a special kind of pro-inflammatory cell death, has been reported to occur in embryonic cortical neurons without interaction with glial cells under some specific conditions, such as poly-deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) exposure [7]. The inflammatory reactions in neurons augment their susceptibility to injury, which aggravate neuronal damage and ultimately lead to death [8]. Protective therapies targeting neuro-inflammation have been considered as a promising area of research in recent years. Meanwhile, the key periods for treatment against inflammation are critical issues that require immediate investigation [9].

Members of the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) receptor associated factor (TRAF) subfamily serve as signaling adaptors in signaling events by coupling TNF receptor superfamily members [10]. To date, seven members of the TRAF family have been discovered, and are named TRAF1–7 in the order of their discovery. Among these members, TRAF6 has the least homology and the greatest difference in the C-terminal domain [11]. TRAF6 is distributed widely and abundantly in the central nervous system (CNS) and contributes to the inflammatory reactions in ischemic stroke [12]. Recently, the role of TRAF6 in the CNS has attracted increasing attention. It has been reported that down-regulation of TRAF6 is an effective target for improving the outcome of ischemic stroke in the cortex of rats [13].

Sirtuin1 (Sirt1) is a nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide-dependent deacetylase that is involved in many biological processes, including cellular metabolism, oxidative stress, gene transcription, and the cellular lifespan [14]. It has been reported that increased expression of Sirt1 in an Alzheimer’s disease model contributes to neuronal survival [15]. Furthermore, the activation level of Sirt1 is associated with ischemia/reperfusion injury [16]. Also, increased Sirt1 expression plays a key role in the ischemic preconditioning-mediated protection against the subsequent ischemia/reperfusion injury in the mouse heart. Sirt1 is regarded as an anti-aging protein because its activation significantly delays the process of aging [17]. Further, since the Sirt1 protein level decreases in the brain of the elderly and a higher incidence of ischemic stroke is found in the elderly, there may be a possibility that Sirt1 is involved in the process of ischemic stroke [18]. However, due to the limitation of knowledge of signaling pathways involving Sirt1, its potential application is limited.

Oxidative stress and post-ischemic inflammatory responses are regarded as vital pathogenic mechanisms responsible for post-ischemic cerebral injury [19]. Oxygen and glucose levels change abruptly after ischemia, inducing subsequent inflammation, autophagy, oxidative stress, and apoptosis due to initial renal ischemia [20]. Emerging evidence indicates that there may be crosstalk between oxidative stress and inflammation in ischemic stroke [21]. However, the underlying scenario is obscure, requiring elucidation. In this current study, we found that the inflammatory reaction was pyroptotic, depending on up-regulated TRAF6, originating from the increased ROS burst after Sirt1 suppression. Sirt1-ROS-TRAF6 is responsible for the progress from oxidative stress to inflammation, which indicates that oxidative stress may be the onset of ischemic injury.

Methods

Animal Models

Experiments were performed at room temperature (RT, 18°C–22°C) on adult male C57BL/6J mice (Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) (weighing 18 g–22 g). All experimental procedures were approved by the Animal Research Committees of Capital Medical University and were carried out in accordance with the in-house guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals of Capital Medical University. The middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO) surgery was carried out as previously reported [22].

N2a Cell Cultures and Treatments

Before experiments, N2a cells were differentiated with serum-deprivation for 12 h as reported previously [23]. Differentiated mouse neuroblastoma N2a cells were cultured in high-glucose DMEM (Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium) supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum and 2 mmol/L L-glutamine at 37°C in a humidified incubator with 5% (v/v) CO2. Cells were re-plated at low density (20,000 cells/cm2), and cultured for 1 day prior to the experiment.

Primary Hippocampal Neuron Culture

Hippocampal neurons were cultured as described previously [24]. Pregnant Wistar rats were anesthetized and the brains of E18–19 embryos obtained by Cesarean section. The hippocampi were removed and incubated with 0.25% trypsin–EDTA for 15 min at 37°C and mechanically dissociated. The resulting single-cell suspension was diluted to a density of 2×105 cells/mL in high-glucose DMEM with 10% fetal bovine serum, 10% equine serum, and 2 mmol/L L-glutamine, then plated in 35-mm cell plates coated with poly-L-lysine (Sigma). Cells were kept at 37°C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2. After 4 h, the medium was replaced by serum-free Neurobasal medium with B27 supplement and 0.5 mmol/L L-glutamine. Every 3 days half of the medium was replaced and the cells were used for experiments 10–14 days after plating.

Oxygen-Glucose Deprivation/Re-oxygenation (OGD/R) of N2a Cells

The OGD/R cellular model was used to simulate ischemia/reperfusion injury in vitro. N2a cells were exposed to OGD (glucose-free DMEM, 5% CO2, 2% O2 and 93% N2 for 1 h)/R (high glucose DMEM supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum, 2 mmol/L L-glutamine, and 5% CO2, 21% O2, and 74% N2 for 1 h or 24 h).

Thiazolyl Blue Tetrazolium Bromide (MTT) Assay

Ten microliters of MTT [3-(4,5-dimethyl-2-thiazolyl)-2,5-diphenyl-2-H-tetrazolium bromide, 5 mg/mL stock in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)] was added into each well of a 96-well plate, and incubated at 37°C for 4 h. Dimethyl sulfoxide (100 μL) was used to solubilize the insoluble blue formazan, and OD values of the mixture were measured with a Bio-Rad microplate reader at 550 nm and 650 nm. All MTT assays involved no less than four separate samples, which were measured in triplicate. The viability of vehicle-treated control cells without OGD exposure was taken as 100% with values for the other groups expressed as a percentage of control.

Measurement of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Production

After treatments and washing with HBSS (Hanks balanced salt solution, Gibco), ROS production was addressed by staining with 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescin diacetate (DCFDA; 5 μmol/L, Sigma) in HBSS for 30 min. The N2a cells were then washed and ROS production of DCFDA-preloaded cells was assessed under a fluorescence microscope (Leica, Germany). NAC (2 mmol/L, Sigma) was used as a scavenger of cytoplasmic ROS. Mito-Tempo (5 μmol/L, Sigma) was used as a scavenger of mitochondrial ROS.

Real-Time qPCR Assessment of Gene Expression

To evaluate the mRNA level of TRAF6, mRNA was isolated with TRIzol reagent from the different groups of N2a cells. The primer pairs for TRAF6 were 5′-CCACCCCTGGAAAGCAAGTA-3′ (forward) and 5′-ATGCAGGCTTTGCAGAACCT-3′(reverse) [25], and for GAPDH were 5’-CCTTCATTGACCTCAACTAC-3’ (forward) and 5’-GGAAGGCCATGCCAGTGAGC-3’ (reverse) [26].

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

The cerebral cortex in the penumbra was put into 1.0 mL PBS, pH 7.4, and immediately frozen on dry ice. Then, the tissue was stored at −80°C until use. To obtain the supernatant, the cortex was thawed on ice and centrifuged at 3,000 rpm for 20 min at 4°C. After that, the supernatant was placed in a new tube for use.

The IL-1β protein level in the supernatant was assessed using an IL-1β kit (R&D Systems, Inc., USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocols. The results were assessed by comparing the samples to the standard curve provided with the kit.

Immunofluorescence Staining

After OGD exposure, N2a cells were treated with anti-caspase-1 (Abcam Technology, Cambridge, MA). After washing, the cells were incubated with Alexa Fluor 594-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) for 2 h at RT. Then the samples were counter-stained with DAPI (Sigma). Images were captured with a fluorescence microscope imaging system (Leica, Germany).

Evaluation of Superoxide Dismutase 2 (SOD2) Enzyme Activity

SOD2 enzymatic activity was measured using a SOD assay kit with WST-8 method (Beyotime Co., S0103) following the manufacturer’s instructions. To separate the activity of SOD2, the inhibitors A and B were added to block the activity of SOD1. The absorption at 450 nm was measured using a microplate reader.

Knock-Down of TRAF6 by Small-Interfering (si)RNA Transfection

N2a cells cultured in 6-well plates were transfected with 180 pmol of TRAF6-specific siRNAs (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA) using Lipofectamine™ 3000 transfection reagent (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The medium was replaced with growth culture medium 5 h after transfection. After the cells had been transfected for 72 h, they were harvested for OGD exposure and subsequent experiments.

Recombinant Lentiviral Vector

Lentiviruses containing sequences encoding rat TRAF6 (lenti-TRAF6, Weijin Biotechnologies Corp., Inc.) was constructed for in vitro studies of hippocampal neurons. The cultured neurons were infected for 72 h with lentiviruses at a multiplicity of infection of 50.

Sample Preparation and Western Blot Analysis

As reported previously [27], frozen samples were rapidly thawed and homogenized at 4°C in Buffer C [50 mmol/L Tris-Cl, pH 7.5, containing 2 mmol/L EDTA, 1 mmol/L EGTA, 100 mmol/L iodoacetamide (an SH-group blocker), 5 mg/mL each of leupeptin, aprotinin, pepstatin A, and chymostatin, 50 mmol/L potassium fluoride, 50 nmol/L okadaic acid, and 5 mmol/L sodium pyrophosphate]. The protein concentration was determined using a BCA kit (Pierce Co., Rockford, IL). Proteins (25 μg) from each sample were loaded for sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis [10% (w/v) SDS gel]. Proteins were then electrophoresed and transferred onto poly-vinylidene difluoride membranes (GE Healthcare, UK) at 4°C. After several rinses with TTBS (20 mmol/L Tris-Cl, pH 7.5, 0.15 mol/L NaCl, and 0.05% Tween-20), the transferred membrane was blocked with 10% non-fat milk in TTBS for 1 h and then incubated with anti-TRAF6 (Abcam Technology, Cambridge, MA), anti-ASC (CST), anti-caspase-1 (Abcam), anti-interleukin 1β (Abcam), and anti-SQSTM1/p62 (Abcam) antibodies and the corresponding secondary antibodies (Stressgen Biotechnologies Corp., Victoria, BC, Canada) for 1 h. After incubation with the primary and secondary antibodies, an enhanced chemiluminescence kit (GE Healthcare, UK) was used to detect signals. To verify equal loading of protein, the blots were re-probed with primary monoclonal antibody against β-actin (Sigma), and GAPDH (CST). Quantitative analysis for immunoblotting was performed after scanning the X-ray film with Quantitative-One software (Gel Doc 2000 imaging system, Bio-Rad Co., CA).

Antibody Array Analysis

One hundred milligrams of cerebral cortex was thawed on ice with 1 mL RIPA (CST, 9806S) containing protease inhibitor and phosphatase inhibitor. Then, the lysate was centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C and the supernatant was placed in a new tube. A BCA protein assay kit (Thermo Scientific) was used to quantify the total protein. Samples were obtained by diluting protein lysate > 10-fold to 0.5 mg/mL with blocking buffer. The total volume was 1 mL for each of the protein samples for antibody array analysis.

Independent replicate antibody array assays were used and the RayBio AAM-INF-1 analysis tool software, provided with the array, was used to assess the signal intensities of identified proteins. Aligned data were normalized with background subtraction from the positive control densities. The positive control of the first sample was regarded as 100% and the signal intensities of other samples were calculated according to the formula: normalized intensity of signal spot = (signal intensity of spot) × (positive signal intensity on reference array/positive signal intensity on sample array) [28].

Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as the mean ± SD. Statistical analysis was conducted by one-way analysis of variance followed by all pair-wise multiple comparison procedures using the Bonferroni test (Sigmastat 10.0). A value of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Ischemia Induces Pyroptosis in Cortical Regions of MCAO Mice

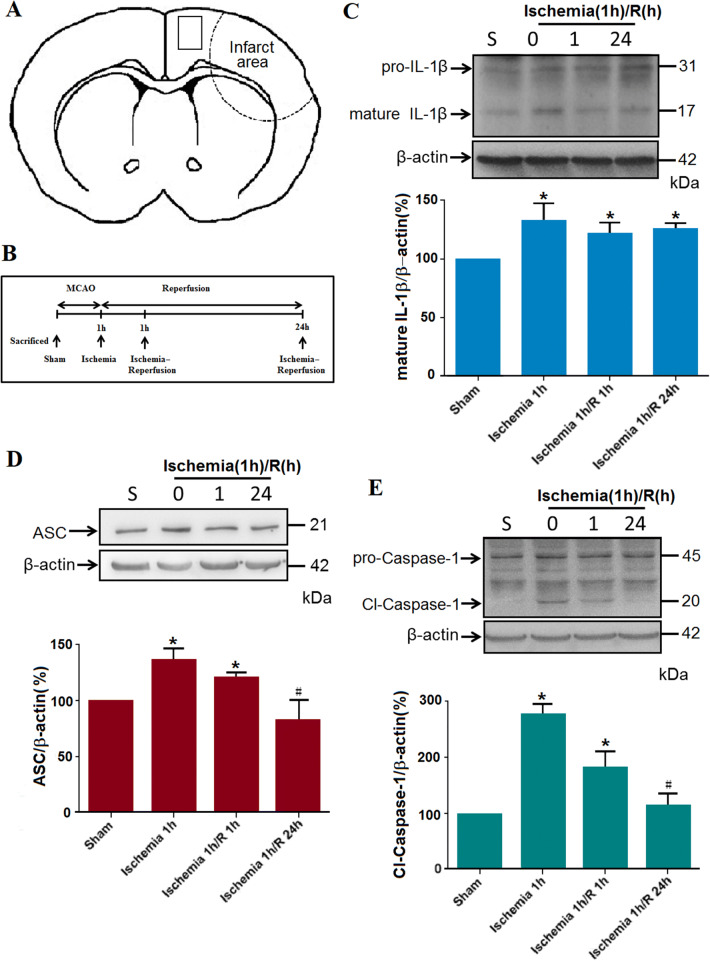

Pyroptosis is characterized as an inflammatory, caspase-1-dependent, and programmed form of cell death. It has been overwhelmingly accepted that pyroptosis is induced by the inflammasome, a multi-protein complex containing apoptosis-associated speck-like protein with a caspase recruitment domain (ASC), an adaptor protein, and caspase-1, an inflammatory cysteine-aspartic protease [7, 29]. To address whether pyroptosis occurs in cortical regions after acute ischemia (Fig. 1A, B), we assessed the levels of IL-1β, ASC, and cleaved caspase-1 in the ischemic rat cortex after MCAO using western blot assays (Fig. 1C–E). The data were collected from four groups: sham, MCAO 1 h, MCAO 1 h/reperfusion 1 h, and MCAO 1 h/reperfusion 24 h. After a 1-h ischemic insult, the mature IL-1β, ASC, and cleaved caspase-1 were all increased and remained at a higher level during the subsequent reperfusion compared with the sham group. Moreover, ASC oligomerization was detected by western blot analysis using a monoclonal antibody against ASC. Of note, ischemia or ischemia/reperfusion resulted in the production of multimers of ASC (Fig. S1). Further, the translocation of caspase-1 to the nuclei of neurons was observed with MAP2, caspase-1, and DAPI staining (Fig. S2) in the peri-ischemic region of MCAO mice, indicating that caspase-1 is activated in some neurons after 1 h of ischemia.

Fig. 1.

MCAO-induced cerebral ischemia results in the pyroptosis of neural cells. A Schematic of the brain showing the areas of selected samples for the following experiments. B Illustration of the experimental protocol. C Representative blots and statistical results for mature IL-1β levels with western blot assay (β-actin was used as the loading control; *P < 0.05; n= 5/group). D Representative blots and statistical results for ASC protein levels (*P < 0.05; n= 5/group). E Representative blots and statistical results for cleaved-caspase-1 protein levels (*P < 0.05, n= 5/group).

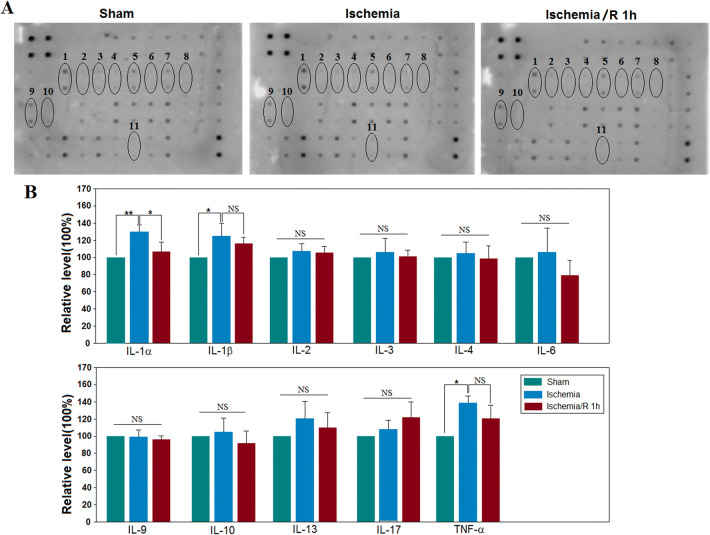

Antibody array analysis in the cerebral cortex of mice from the sham, naïve ischemia (1 h), or ischemia (1 h)/reperfusion (1 h) groups was performed using the RayBio® Label–based array containing duplicate spots of 40 proteins. We emphasized 11 cytokines (Fig. 2A). Among the 10 identified cytokines, the expression of IL-1α, IL-1β, and TNF-α increased significantly after the ischemic insult and subsequent reperfusion (P < 0.05 vs control, n= 3/group; Fig. 2B). These results indicated that there was an inflammatory reaction in the ischemic stage. These results suggest an interesting phenomenon: the early inflammatory responses of neural cells are mainly in the pyroptotic mode, which may be the gateway to the subsequent injury.

Fig. 2.

MCAO-induced cerebral ischemia (1 h) increases the levels of IL-1α, IL-1β, and TNF-α, while the subsequent reperfusion (1 h) reduces the inflammatory cytokines. A Representative results of cerebral tissue influenced by MCAO-induced injury. The regions 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, and 11 represent the blots of IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-2, IL-3, IL-4, IL-6, IL-9, IL-10, IL-13, IL-17, and TNF-α. B Statistical results showing that MCAO-induced ischemia increases the relative levels of IL-1α, IL-1β, and TNF-α (*P < 0.05 vs sham, n= 3/group). Meanwhile, the increased level of IL-1α, but not IL-1β and TNF-α, was reduced after the subsequent 1 h of reperfusion.

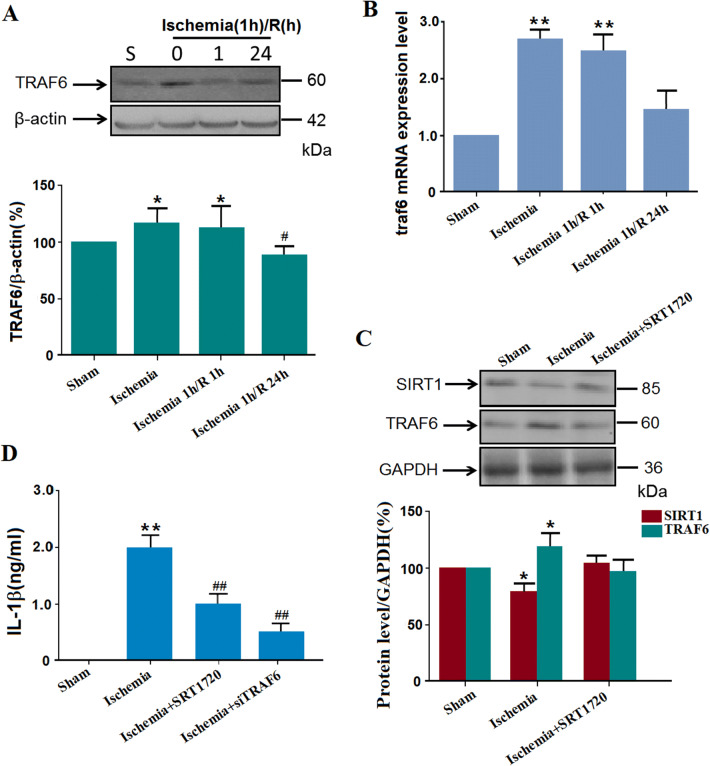

TRAF6 Protein Levels Increase Due to Decreased Sirt1 Protein Levels in the Cortex of Naïve Ischemic Mice

TRAF6 is the only member of the TRAF subfamily to participate in Toll-like receptor signaling to the nuclear factor of kappa light polypeptide gene enhancer (NF-κB), which plays a vital role in inflammatory reactions [30, 31]. To explore whether TRAF6 is involved in this ischemia-induced inflammatory reaction, TRAF6 protein levels were assessed with western blot assays (Fig. 3A). We found that naïve ischemic or ischemia 1 h/R 1 h significantly increased the TRAF6 protein levels (Fig. 3A). Further, to determine whether the increased level of TRAF6 resulted from increased synthesis, qPCR was used to confirm the mRNA level of traf6 (Fig. 3B). The traf6 mRNA levels in the ischemia and ischemia 1 h/R 1 h groups were significantly higher than that in the sham group. Also, the Sirt1 protein levels were decreased by ischemic insults. And when the agonist of Sirt1, SRT1720, was injected intracerebroventricularly before surgery, no increase in TRAF6 protein levels was induced by cerebral ischemia, indicating that the Sirt1 activation may result in the activation of TRAF6 (Fig. 3C). Further, when TRAF6-specific siRNAs or SRT1720 were injected intracerebroventricularly before surgery, the increased IL-1β in the supernatant induced by ischemic insults was suppressed (Fig. 3D).

Fig. 3.

MCAO-induced cerebral ischemia (1 h) increases the TRAF6 protein levels. A Representative blots and statistics for the TRAF6 protein levels in western blot assays (*P < 0.05 vs sham; #P < 0.01 vs ischemia group; n= 5/group). B qPCR results showing the mRNA levels of TRAF6 in naïve ischemia, ischemia 1 h/R 1 h, and sham groups (**P < 0.01; n= 8/group). C Salvage of the ischemia-increased TRAF6 protein level by intracerebroventricular injection of the Sirt1 activator SRT1720 (50 μg/kg) (*P < 0.05, n= 5/group). D ELISA of supernatant IL-1β levels after ischemic insults and the effects of SRT1720 or TRAF6-specific siRNA (**P < 0.01 vs sham; n= 6/group; ##P < 0.01 vs ischemia group; n= 6/group; NC, negative control).

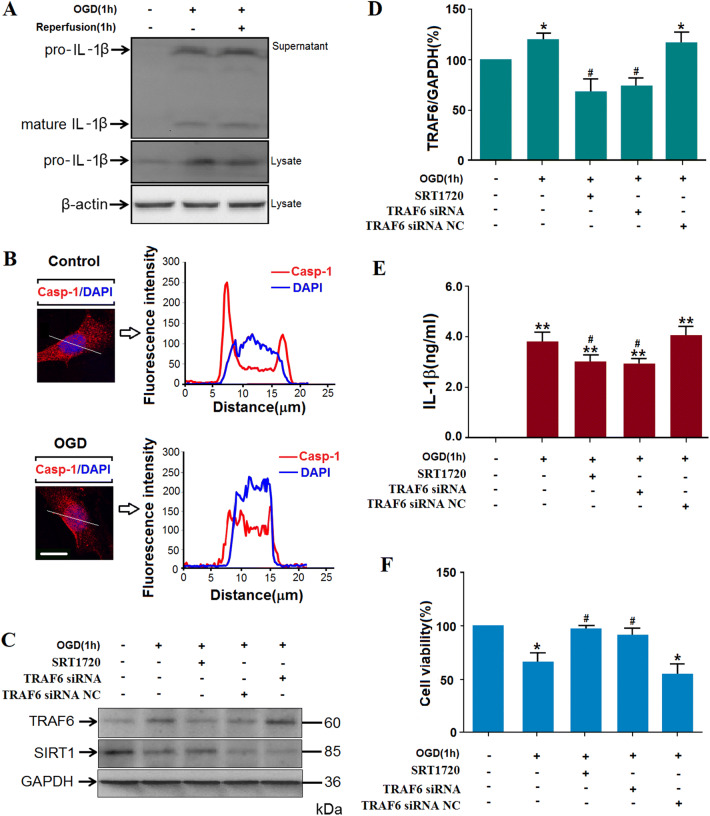

Suppression of TRAF6 or Increased Sirt1 Protein Levels in N2a Cells Decreased the Pyroptosis and Subsequent Death of OGD/R Cells

Based on the crucial role of TRAF6 in inflammation and the current in vivo results [32], we still needed to further explore the detailed mechanism of the Sirt1-TRAF6 signaling pathway in inflammatory reactions under ischemic stress. The following experiments were carried out in differentiated N2a cells (Fig. S3). First, pyroptosis in N2a cells under ischemic stress was assessed by the levels of pro-inflammatory IL-1β and activation of caspase-1. After 1 h OGD, mature IL-1β and the protein level of pro-IL-1β increased significantly (Figs. 4A and S4), while the cleaved caspase-1 translocated to the nuclei (Fig. 4B). Second, the TRAF6 protein levels increased after ischemia (Fig. 4C, D; statistical results of Sirt1 protein levels in Fig. S5). When the activator of Sirt1, SRT1720, or TRAF6-specific siRNA was added before OGD, the increase in TRAF6 protein levels was reduced, indicating that Sirt1 is upstream of TRAF6. Third, both the increased TRAF6 and decreased Sirt1 protein levels resulted in IL-1β production in the supernatant of OGD-treated N2a cells (Fig. 4E). Fourth, cell viability measured with the MTT assay was reduced after OGD and rescued after TRAF6 was knocked down or Sirt1 was activated (Fig. 4F). All these phenomena considered as a whole suggest the occurrence of pyroptosis of N2a cells via the Sirt1-TRAF6 signaling pathway after OGD. Since induced pyroptosis is deleterious and sustained cytokines are harmful, further study is warranted.

Fig. 4.

Oxygen-glucose deprivation (OGD) causes pyroptosis in N2a cells. A Representative image showing pro-IL-1β protein levels in cells and mature IL-1β in supernatants after 1 h OGD and the subsequent re-oxygenation. B Representative images showing translocation of cleaved caspase-1 to the nucleus by confocal microscopy in N2a cells exposed to OGD (line tracings correspond to marked area; scale bar, 10 μm). C Representative blots of TRAF6 protein levels in N2a cells. D Analysis of TRAF6 protein levels as in C (*P < 0.05 vs normoxia; n= 5 group). When the cells were transfected with TRAF6-specific siRNA or pretreated with SRT1720, the increased TRAF6 protein levels were reduced (#P < 0.05 vs OGD group; n= 5/group; NC, negative control). E ELISA of mouse IL-1β in supernatants of OGD-treated N2a cells and after transfection of TRAF6 siRNA or SRT1720 (**P < 0.01 vs normoxia; #P < 0.05 vs OGD group; n= 6/group). F Quantitative analysis of MTT assay showed that OGD decreased cell viability (*P < 0.05 vs control; n= 6/group). When the N2a cells were transfected with TRAF6 siRNA or pretreated with SRT1720, the viability was salvaged significantly (#P < 0.05 vs OGD/R group; n= 6/group).

OGD-Induced Reduction of Sirt1 Contributes to ROS Production, Followed by TRAF6 Activation

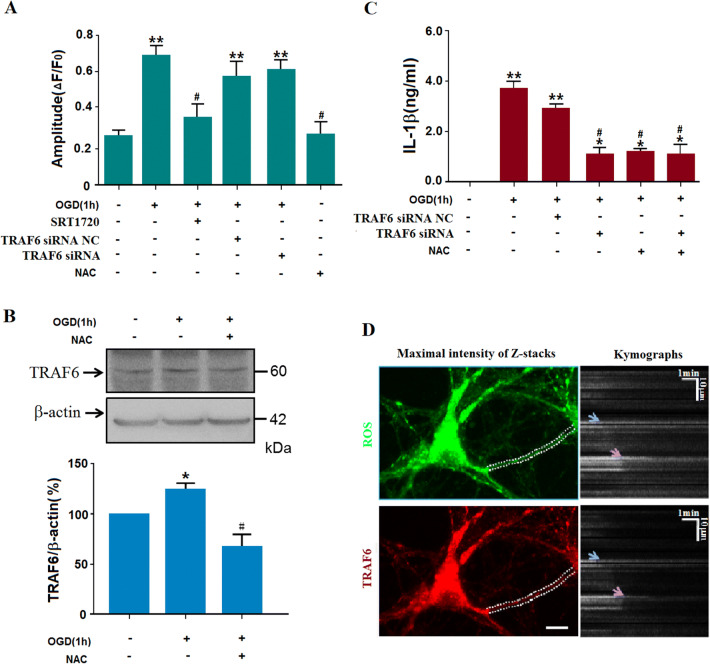

It has been reported that there is a close relationship between ROS and inflammatory responses [33]. To explore whether ROS is involved in the relationship between Sirt1 and TRAF6 under our experimental conditions, the intercellular ROS level was assessed by DCF staining. N2a cells were pretreated with TRAF6-specific siRNAs before OGD. ROS production increased after OGD exposure, and remained at a similar level when the TRAF6-specific siRNAs were added. NAC, a ROS scavenger, was used as the positive control, and this significantly reduced the ROS level (Fig. 5A). Both NAC and TRAF6-specific siRNAs decreased OGD-induced neuronal death (Fig. 5B). Moreover, NAC treatment reversed the OGD-induced increase in TRAF6 protein level (Fig. 5C), indicating that ROS is upstream of TRAF6. Further, when Sirt1 was activated with SRT1720, the ROS level decreased, which had shown a burst after OGD exposure (Fig. 5A). Finally, when NAC and TRAF6-specific siRNAs were added to the medium before the ischemic insult, the increased IL-1β secretion was significantly suppressed (Fig. 5C). Besides, when the Sirt1 protein level was knocked down with siRNAs, the ROS production increased significantly (Fig. S6). Moreover, TRAF6 knockdown had no effect on the Sirt1 protein level (Fig. S5). The current results indicated that pyroptosis in N2a cells is induced by increased TRAF6 via the Sirt1-ROS signaling pathway.

Fig. 5.

ROS-mediated activation of TRAF6 plays an important role in OGD-induced injury. A OGD exposure increased the ROS production, which was reduced by NAC and SRT1720, but not TRAF6-specific siRNA (**P < 0.01 vs normoxia group, #P < 0.05 vs OGD group; n= 3/group). B Pretreatment with NAC suppressed OGD-induced activation of TRAF6 (*P < 0.05 vs normoxia group, #P < 0.05 vs OGD group; n= 5/group). C ELISA of mouse IL-1β in supernatants of OGD-treated N2a cells showing that OGD increased IL-1β secretion, which was blocked by treatment with NAC or TRAF6-specific siRNA (**P < 0.01 vs normoxia, #P < 0.05 vs OGD group; n= 6). D Representative images of a dendritic ROS burst and TRAF6 accumulation after OGD and subsequent NAC treatment. Left, DCF fluorescence revealing ROS and TRAF6 signals in a dendritic segment (dashed lines, boundaries of dendrite; scale bar, 10 μm); right, kymographs with ImageJ software show the two signals decayed at almost the same time (arrows) after 15–19 min after NAC treatment (because DCF is apt to enrichment in mitochondria, the images were acquired within 30 min after washes).

To further explore the correlation between ROS and TRAF6, serial images of ROS and lenti-RFP-TRAF6 were recorded. The dynamic changes in ROS and TRAF6 were analyzed with Flash Sniper software and presented with ImageJ (Fig. 5D). To obtain precise signals of ROS and TRAF6, we measured the fluorescence intensities of ROS and TRAF6 in the dendritic processes of primary cultured hippocampal neurons where there were fewer overlapping signals and less noise. The neurons were subjected to OGD for 30 min, and then treated with NAC. The OGD-induced accumulation of TRAF6 was attenuated with the decay of the ROS burst. Based on the scavenging of ROS by NAC and the similar decay onset of the ROS burst and TRAF6 accumulation, it is likely that the ROS burst in the cytoplasm contributes to the TRAF6 accumulation.

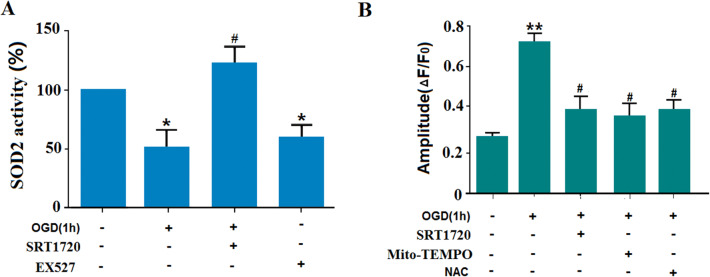

Reduction of Sirt1 Increases ROS Levels in a SOD2-Dependent Manner

SOD2 plays a key role in the production of ROS as the vital mitochondrial oxidative scavenger [34]. To explore whether the Sirt1-induced ROS production depends on SOD2, its activity was investigated under different experimental conditions. We found that OGD exposure suppressed the SOD2 activity. However, SRT1720, the Sirt1 activator, salvaged the SOD2-dependent actions. Moreover, EX527 (5 mmol/L; an inhibitor of Sirt1) decreased the SOD2-mediated actions, and this served as a positive control here (Fig. 6A). To further strengthen our conclusion, we measured cytoplasmic ROS using DCF staining. OGD significantly increased the ROS level in the cytoplasm, and this was suppressed by pretreatment with 5 μmol/L SRT1720 or 200 μmolpyroptosis in long-term ischemic injury/L Mito-Tempo. Based on the scavenging of mitochondrial ROS by Mito-Tempo, it can be deduced that the OGD-induced ROS burst in the cytoplasm is derived from mitochondria (Fig. 6B). So, the decreased SOD2-mediated activity contributes to the cytoplasmic ROS burst. Sirt1 plays a vital role in ROS production in a SOD2-dependent manner under OGD. Now, there are two possibilities for the role of Sirt1 in SOD2 modulation. One is that Sirt1 may translocate to mitochondria for its activity, but we did not find this in the current study. Another is that other molecules may be involved in the interaction between Sirt1 and SOD2; this deserves to be thoroughly explored.

Fig. 6.

OGD exposure increases ROS levels in the cytoplasm of N2a cells via the SIRT1-SOD2 pathway. A SOD2 activity was suppressed by OGD exposure, and salvaged by SRT1720, an activator of SIRT1 (EX527 treatment group served as a positive control). B ROS levels in the cytoplasm of N2a cells were increased by OGD exposure. SRT1720, Mito-Tempo, and NAC treatment decreased the OGD-induced ROS burst (*P < 0.05 vs controls, #P < 0.05 vs OGD group). All experiments were repeated three times.

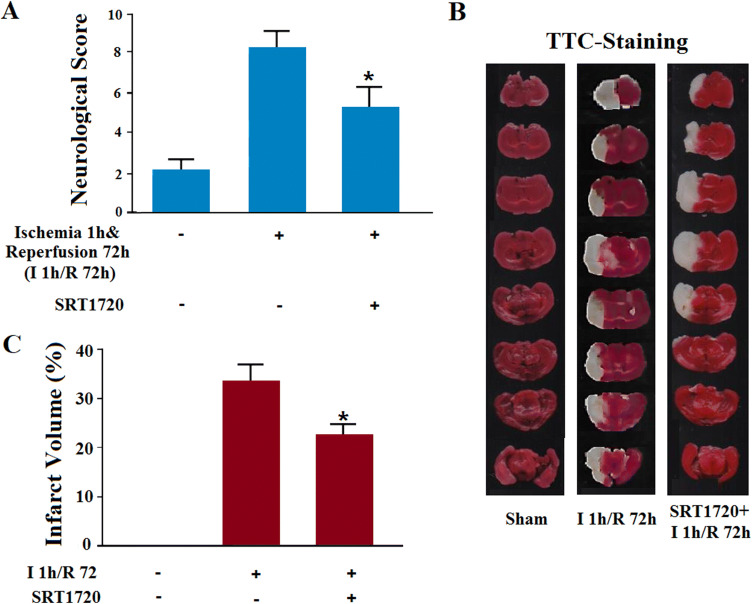

Anti-oxidative Stress Therapy Alleviates the Ischemic Injury in MCAO Mice

Neuronal injury starts from the acute stage of stroke, and then a second progressive injury occurs during the sub-acute period [35]. Among the mechanisms, the importance of early pyroptosis in long-term ischemic injury needs to be further elucidated. The following experiment was carried out on MCAO mice with ischemia for 1 h and reperfusion for 72 h. After the agonist of Sirt1 was injected intracerebroventricularly 30 min before the MCAO surgery (Fig. 7A), the infarct volume declined and the neurological score improved (Fig. 7B, C). Since the decreased action of Sirt1 occurred in the early onset of pyroptosis, gain-of-function of Sirt1 was thought to act via the early suppression of inflammation. Our results indicated that the mechanism responsible for the late ischemia-induced injury may ‘hitch a ride’ on the early inflammatory reactions, among which the early pyroptosis is especially worthy of note.

Fig. 7.

Gain-of-function of Sirt1 alleviates ischemia-induced injury in MCAO mice (ischemia 1 h/reperfusion 72 h).A SRT1720 alleviated MCAO-increased neurological score (*P < 0.05 vs ischemia group; n= 6/group).B Representative images of TTC-stained cerebral slices from mice subjected to sham, naïve ischemia, or ischemia 1 h/R 72 h. C SRT1720 alleviated MCAO-increased infarct volume (*P < 0.05 vs ischemia group; n= 6/group).

Discussion

Post-ischemic inflammation has been reported to be involved in neural cell death in the acute and sub-acute stages, along with the other mechanisms responsible for the pathogenesis of stroke [36]. Barrett et al. proposed that neuro-inflammation may be the main gateway to secondary cerebral injury in stroke [37]. Over the past years, many studies have emphasized the inflammatory responses induced by ischemic stroke for improving the outcome. However, initial treatments targeting inflammatory reactions against acute ischemic stroke have failed [38], and this is thought to be due to the nature of immune cells in stroke. Inflammatory reactions participate in the process of post-ischemic injury. Besides, they are also involved in post-stroke repair and regeneration [39]. Whether inflammatory responses constitute an initial event or consequence of ischemic stroke has been a frequent topic of debate; however, the increasing number of ischemic stroke-associated genes being addressed in inflammatory pathways indicates a causative role, at least in part. In the present study, we demonstrated a definite inflammatory burst as pyroptosis at the early stage of stroke. Combined with the previous study, interventions in inflammatory reactions should be taken into consideration from the early to the late stages of stroke.

Sirt1, regarded as a bio-energetic regulator, serves as the onset of the subsequent oxidative stress in cerebral stroke [40]. Sirt1 warrants special interest since it is involved in both gene expression and cell metabolism under the cellular stress induced by cerebral ischemia [41]. The strategy of Sirt1 activation may alleviate stroke injury via the suppression of apoptosis and inflammation [42]. Based on its importance in ischemic stroke, the serum Sirt1 concentration is a promising means of evaluating functional outcomes, including dementia, anxiety, and depression in patients with acute ischemia [43]. Here, we found decreased Sirt1 protein levels both in vivo and in vitro, and this was followed by increased ROS and TRAF6 activation, indicating that Sirt1 indicates the onset of oxidative stress and inflammatory responses follow. So, treatment by Sirt1 activation may be an effective strategy for ischemic stroke. Moreover, the relationship between Sirt1-induced pathological processes and its role at different stages of ischemic stroke deserves further study.

The activation of Sirt1 has been reported to play a key role in the anti-oxidative stress pathway via the Sirt1-FOXOs signaling pathway, which results in the release of high levels of ROS [44]. Then, an inflammatory response is elicited and systemic inflammation occurs [45]. In a rat model of traumatic brain injury, TRAF6 protein levels are significantly increased on day 7 after injury, in both neurons and astrocytes. These results show that TRAF6 is important for both neurons and astrocytes in stress injury [46]. Strikingly, in the present study, we found that the increase in TRAF6 was initiated by the ROS burst, suggesting that early inflammatory reactions may occur via the ROS-TRAF6 signaling pathway. Based on the current results, we determined that TRAF6-mediated pyroptosis occurs at the early stage of the post-ischemic period. Although it is a special kind of inflammation-induced programmed death, the same phenomena occurred, such as the increased level of TNF-α. Both our current results and those reported previously suggested that the TRAF6 protein level is important for neuronal survival and is an effective target for stroke treatment.

Oxidative stress is a crucial mechanism during I/R injury, and the production of ROS is an important contributor to cerebral I/R injury [47]. The increased ROS by I/R mainly results from the mitochondrial electron transport chain [48]. ROS has been reported to initiate and augment neuronal apoptosis after I/R. The current data suggest that cytoplasmic ROS is vital for cerebral damage-induced inflammation following I/R [49]. However, it remains obscure how Sirt1 regulates the ROS burst after ischemia. Our results indicated that the decrease of ROS level reduced ischemia-induced TRAF6 accumulation and the ischemia-induced injury. The Sirt1-mediated signaling pathway for ROS production may require deeper investigation.

During pyroptosis, proteolytic cleavage of caspase-1 transforms pro-IL-1β into its mature form, which further activates the NF-κB pathway to take part in cerebral innate immunity and inflammation via the production and action of other inflammatory cytokines [50]. IL-1 is a pro-inflammatory cytokine that is regarded as a vital mediator and the major effector of injury in experimental cerebral ischemic stroke or excitotoxicity in rodents [51]. Both IL-1α and IL-1β are produced soon after exposure to cerebral ischemia [52]. Inhibiting the actions of IL-1α and IL-1β with the IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1Ra) provides a protective strategy in experimental models of stroke [53]. Knock-out of both IL-1α and IL-1β significantly alleviates the ischemia-induced injury in response to experimental stroke [54]. Although IL-1α and IL-1β signal through a common receptor (IL-1RI), they have different actions in sterile inflammation [55]. And, different from IL-1β, the release of IL-1α is not caspase-1 dependent [56]. It has also been reported that IL-1α expression precedes IL-1β after cerebral ischemic insults [57]. In the present study, the expression of IL-1α and IL-1β increased after acute ischemia and IL-1α, but not IL-1β, declined after the subsequent reperfusion. Although the burst of mature IL-1β was determined to be consistent with the scenario of pyroptosis, the regulatory mechanism of IL-1α remains obscure and should be explored further.

Generally, inflammasomes are cytoplasmic supra-structured complexes that are formed after the signals of exogenous invasion or endogenous injury are sensed [58, 59]. Among these, the formation of NLRP3-centered complexes is vital for the activation of NLRP3 and the occurrence of pyroptosis. And, these complexes may derive from the combination of NLRP3 with ASC or NEK7 [60, 61]. Meanwhile, there is also a caspase recruitment domain in the structure of the ASC protein, resulting in caspase dimerization and activation [62, 63]. In our study, there may be a kind of ASC-centered complex with caspase-1 based on the activation of ASC and caspase-1. Due to the importance of supra-structured complexes in the inflammation, study of the formation of complexes and their gain-of-function should be emphasized in further studies.

N2a cells are derived from a mouse neuroblastoma cell line from a spontaneous tumor in an albino strain A mouse. Differentiated N2a cells possess many neuronal characteristics and express many neuronal markers [64]. Based on their neuronal characteristics, N2a cells have been widely used in many areas of study, including ischemia, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, and Alzheimer’s disease [19, 65, 66]. However, LePage et al. also reported that negative cytotoxicity data obtained using neuroblastoma cell lines should be viewed with caution because N2a cells are less sensitive to neurotoxicity than cerebellar granule neurons [67]. Here, we mainly used N2a cells to study neuro-inflammation. Although we demonstrated significant phenomena, the experimental conditions we used may not be suitable for primary neuronal cultures, which is a limitation of our study.

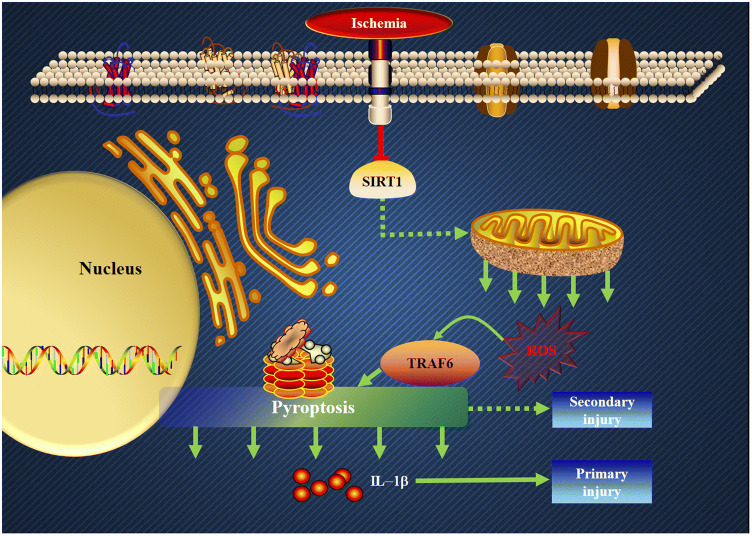

From the current findings, we can draw the following conclusions (Fig. 8). First, inflammatory reactions occur during the early stage of ischemic stroke. Second, the increased production of ROS that results from a decreased Sirt1 protein level plays an important role in the inflammatory reactions involving TRAF6. Third, there is crosstalk between oxidative stress and pyroptosis at the early stage of ischemic stroke. Fourth, the decreased Sirt1 protein level is the onset of early inflammatory reactions. Fifth, pyroptosis is mediated by the Sirt1-ROS-TRAF6 signaling pathway. Sixth, the pyroptosis in neuronal cells is harmful, and can be suppressed in both an anti-oxidative stress manner and an anti-inflammation manner. Although we cannot disclose the whole scenario of the interaction between oxidative stress and inflammatory reactions during ischemic insults, the results suggest primarily that this is a promising prospect in further stroke research. In sum, based on our current results, we propose that the therapeutic strategies against inflammatory reactions should place emphasis on neuronal protection even at the early stage of ischemic stroke.

Fig. 8.

Schematic of how Sirt1-ROS-TRAF6-induced pyroptosis contributes to the early neural injury after ischemia (red line, inhibitory effect; green arrows, positive correlations between members of the signaling cascade).

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31771292 and 31571162). We thank Professor Heping Cheng, Peking University, for kindly supporting the analytical methods for the fluorescence images.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Weijie Yan and Wei Sun have contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Katan M, Luft A. Global burden of stroke. Semin Neurol. 2018;38:208–211. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1649503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stoll G, Jander S, Schroeter M. Inflammation and glial responses in ischemic brain lesions. Prog Neurobiol. 1998;56:149–171. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(98)00034-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moskowitz MA. Brain protection: maybe yes, maybe no. Stroke. 2010;41:S85–86. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.598458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Del Zoppo GJ, Saver JL, Jauch EC, Adams HP, Jr, American Heart Association Stroke C Expansion of the time window for treatment of acute ischemic stroke with intravenous tissue plasminogen activator: a science advisory from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2009;40:2945–2948. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.192535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sekerdag E, Solaroglu I, Gursoy-Ozdemir Y. Cell death mechanisms in stroke and novel molecular and cellular treatment options. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2018;16:1396–1415. doi: 10.2174/1570159X16666180302115544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shukla V, Shakya AK, Perez-Pinzon MA, Dave KR. Cerebral ischemic damage in diabetes: an inflammatory perspective. J Neuroinflammation. 2017;14:21. doi: 10.1186/s12974-016-0774-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adamczak SE, de Rivero Vaccari JP, Dale G, Brand FJ, 3rd, Nonner D, Bullock MR, et al. Pyroptotic neuronal cell death mediated by the AIM2 inflammasome. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2014;34:621–629. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2013.236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ceulemans AG, Zgavc T, Kooijman R, Hachimi-Idrissi S, Sarre S, Michotte Y. The dual role of the neuroinflammatory response after ischemic stroke: modulatory effects of hypothermia. J Neuroinflammation. 2010;7:74. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-7-74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ahmad M, Graham SH. Inflammation after stroke: mechanisms and therapeutic approaches. Transl Stroke Res. 2010;1:74–84. doi: 10.1007/s12975-010-0023-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xie P. TRAF molecules in cell signaling and in human diseases. J Mol Signal. 2013;8:7. doi: 10.1186/1750-2187-8-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee NK, Lee SY. Modulation of life and death by the tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factors (TRAFs) J Biochem Mol Biol. 2002;35:61–66. doi: 10.5483/bmbrep.2002.35.1.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lomaga MA, Henderson JT, Elia AJ, Robertson J, Noyce RS, Yeh WC, et al. Tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor 6 (TRAF6) deficiency results in exencephaly and is required for apoptosis within the developing CNS. J Neurosci. 2000;20:7384–7393. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-19-07384.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang J, Fu B, Zhang X, Chen L, Zhang L, Zhao X, et al. Neuroprotective effect of bicyclol in rat ischemic stroke: down-regulates TLR4, TLR9, TRAF6, NF-kappaB, MMP-9 and up-regulates claudin-5 expression. Brain Res. 2013;1528:80–88. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2013.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rajendran R, Garva R, Krstic-Demonacos M, Demonacos C. Sirtuins: molecular traffic lights in the crossroad of oxidative stress, chromatin remodeling, and transcription. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2011;2011:368276. doi: 10.1155/2011/368276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xu J, Jackson CW, Khoury N, Escobar I, Perez-Pinzon MA. Brain SIRT1 mediates metabolic homeostasis and neuroprotection. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2018;9:702. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2018.00702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Duan J, Yin Y, Wei G, Cui J, Zhang E, Guan Y, et al. Chikusetsu saponin IVa confers cardioprotection via SIRT1/ERK1/2 and Homer1a pathway. Sci Rep. 2015;5:18123. doi: 10.1038/srep18123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blokh D, Stambler I. Information theoretical analysis of aging as a risk factor for heart disease. Aging Dis. 2015;6:196–207. doi: 10.14336/AD.2014.0623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meng X, Tan J, Li M, Song S, Miao Y, Zhang Q. Sirt1: Role under the condition of ischemia/hypoxia. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2017;37:17–28. doi: 10.1007/s10571-016-0355-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang CP, Shi YW, Tang M, Zhang XC, Gu Y, Liang XM, et al. Isoquercetin ameliorates cerebral impairment in focal ischemia through anti-oxidative, anti-inflammatory, and anti-apoptotic effects in primary culture of rat hippocampal neurons and hippocampal CA1 region of rats. Mol Neurobiol. 2017;54:2126–2142. doi: 10.1007/s12035-016-9806-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hadj Abdallah N, Baulies A, Bouhlel A, Bejaoui M, Zaouali MA, Ben Mimouna S, et al. Zinc mitigates renal ischemia-reperfusion injury in rats by modulating oxidative stress, endoplasmic reticulum stress, and autophagy. J Cell Physiol. 2018;233:8677–8690. doi: 10.1002/jcp.26747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nasoohi S, Ismael S, Ishrat T. Thioredoxin-interacting protein (TXNIP) in cerebrovascular and neurodegenerative diseases: Regulation and implication. Mol Neurobiol. 2018;55:7900–7920. doi: 10.1007/s12035-018-0917-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang N, Yin Y, Han S, Jiang J, Yang W, Bu X, et al. Hypoxic preconditioning induced neuroprotection against cerebral ischemic injuries and its cPKCgamma-mediated molecular mechanism. Neurochem Int. 2011;58:684–692. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2011.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang YP, Wang ZF, Zhang YC, Tian Q, Wang JZ. Effect of amyloid peptides on serum withdrawal-induced cell differentiation and cell viability. Cell Res. 2004;14:467–472. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7290249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Evans MS, Collings MA, Brewer GJ. Electrophysiology of embryonic, adult and aged rat hippocampal neurons in serum-free culture. J Neurosci Methods. 1998;79:37–46. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(97)00159-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sundar R, Gudey SK, Heldin CH, Landstrom M. TRAF6 promotes TGFbeta-induced invasion and cell-cycle regulation via Lys63-linked polyubiquitination of Lys178 in TGFbeta type I receptor. Cell Cycle. 2015;14:554–565. doi: 10.4161/15384101.2014.990302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Muller L, Tokay T, Porath K, Kohling R, Kirschstein T. Enhanced NMDA receptor-dependent LTP in the epileptic CA1 area via upregulation of NR2B. Neurobiol Dis. 2013;54:183–193. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2012.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li Y, Sun W, Han S, Li J, Ding S, Wang W, et al. IGF-1-involved negative feedback of NR2B NMDA subunits protects cultured hippocampal neurons against NMDA-induced excitotoxicity. Mol Neurobiol. 2017;54:684–696. doi: 10.1007/s12035-015-9647-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yumnam S, Venkatarame Gowda Saralamma V, Raha S, Lee HJ, Lee WS, Kim EK, et al. Proteomic profiling of human HepG2 cells treated with hesperidin using antibody array. Mol Med Rep. 2017;16:5386–5392. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2017.7232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martinon F, Burns K, Tschopp J. The inflammasome: a molecular platform triggering activation of inflammatory caspases and processing of proIL-beta. Mol Cell. 2002;10:417–426. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00599-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Newton K, Dixit VM. Signaling in innate immunity and inflammation. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2012, 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Abdullah M, Berthiaume JM, Willis MS. Tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor 6 as a nuclear factor kappa B-modulating therapeutic target in cardiovascular diseases: at the heart of it all. Transl Res. 2018;195:48–61. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2017.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ren M, Guo Y, Wei X, Yan S, Qin Y, Zhang X, et al. TREM2 overexpression attenuates neuroinflammation and protects dopaminergic neurons in experimental models of Parkinson’s disease. Exp Neurol. 2018;302:205–213. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2018.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee CW, Chi MC, Hsu LF, Yang CM, Hsu TH, Chuang CC, et al. Carbon monoxide releasing molecule-2 protects against particulate matter-induced lung inflammation by inhibiting TLR2 and 4/ROS/NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Mol Immunol. 2019;112:163–174. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2019.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kirby K, Hu J, Hilliker AJ, Phillips JP. RNA interference-mediated silencing of Sod2 in Drosophila leads to early adult-onset mortality and elevated endogenous oxidative stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:16162–16167. doi: 10.1073/pnas.252342899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Andrabi SS, Ali M, Tabassum H, Parveen S, Parvez S. Pramipexole prevents ischemic cell death via mitochondrial pathways in ischemic stroke. Dis Model Mech 2019, 12. 10.1242/dmm.033860 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Dirnagl U, Iadecola C, Moskowitz MA. Pathobiology of ischaemic stroke: an integrated view. Trends Neurosci. 1999;22:391–397. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(99)01401-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Barrett KM, Lal BK, Meschia JF. Stroke: advances in medical therapy and acute stroke intervention. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2015;17:79. doi: 10.1007/s11886-015-0637-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.del Zoppo GJ. Acute anti-inflammatory approaches to ischemic stroke. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1207:143–148. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05761.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Drieu A, Martinez de Lizarrondo S, Rubio M. Stopping inflammation in stroke: Role of ST2/IL-33 signaling. J Neurosci. 2017;37:9614–9616. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1863-17.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kalaivani P, Ganesh M, Sathiya S, Ranju V, Gayathiri V, Saravana Babu C. Alteration in bioenergetic regulators, SirT1 and Parp1 expression precedes oxidative stress in rats subjected to transient cerebral focal ischemia: molecular and histopathologic evidences. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2014;23:2753–2766. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2014.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Petegnief V, Planas AM. SIRT1 regulation modulates stroke outcome. Transl Stroke Res. 2013;4:663–671. doi: 10.1007/s12975-013-0277-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lv H, Wang L, Shen J, Hao S, Ming A, Wang X, et al. Salvianolic acid B attenuates apoptosis and inflammation via SIRT1 activation in experimental stroke rats. Brain Res Bull. 2015;115:30–36. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2015.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liang X, Liu Y, Jia S, Xu X, Dong M, Wei Y. SIRT1: The value of functional outcome, stroke-related dementia, anxiety, and depression in patients with acute ischemic stroke. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2019;28:205–212. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2018.09.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang T, Gu J, Wu PF, Wang F, Xiong Z, Yang YJ, et al. Protection by tetrahydroxystilbene glucoside against cerebral ischemia: involvement of JNK, SIRT1, and NF-kappaB pathways and inhibition of intracellular ROS/RNS generation. Free Radic Biol Med. 2009;47:229–240. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Settembre C, Annunziata I, Spampanato C, Zarcone D, Cobellis G, Nusco E, et al. Systemic inflammation and neurodegeneration in a mouse model of multiple sulfatase deficiency. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:4506–4511. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700382104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chen J, Wu X, Shao B, Zhao W, Shi W, Zhang S, et al. Increased expression of TNF receptor-associated factor 6 after rat traumatic brain injury. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2011;31:269–275. doi: 10.1007/s10571-010-9617-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ten VS, Starkov A. Hypoxic-ischemic injury in the developing brain: the role of reactive oxygen species originating in mitochondria. Neurol Res Int. 2012;2012:542976. doi: 10.1155/2012/542976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hu S, Cheng D, Peng D, Tan J, Huang Y, Chen C. Leptin attenuates cerebral ischemic injury in rats by modulating the mitochondrial electron transport chain via the mitochondrial STAT3 pathway. Brain Behav. 2019;9:e01200. doi: 10.1002/brb3.1200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kalogeris T, Bao Y, Korthuis RJ. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species: a double edged sword in ischemia/reperfusion vs preconditioning. Redox Biol. 2014;2:702–714. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2014.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang Y, Liu L, Peng YL, Liu YZ, Wu TY, Shen XL, et al. Involvement of inflammasome activation in lipopolysaccharide-induced mice depressive-like behaviors. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2014;20:119–124. doi: 10.1111/cns.12170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Touzani O, Boutin H, Chuquet J, Rothwell N. Potential mechanisms of interleukin-1 involvement in cerebral ischaemia. J Neuroimmunol. 1999;100:203–215. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(99)00202-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang X, Yue TL, Barone FC, White RF, Gagnon RC, Feuerstein GZ. Concomitant cortical expression of TNF-alpha and IL-1 beta mRNAs follows early response gene expression in transient focal ischemia. Mol Chem Neuropathol. 1994;23:103–114. doi: 10.1007/BF02815404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Brough D, Tyrrell PJ, Allan SM. Regulation of interleukin-1 in acute brain injury. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2011;32:617–622. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2011.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Boutin H, LeFeuvre RA, Horai R, Asano M, Iwakura Y, Rothwell NJ. Role of IL-1alpha and IL-1beta in ischemic brain damage. J Neurosci. 2001;21:5528–5534. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-15-05528.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rider P, Carmi Y, Guttman O, Braiman A, Cohen I, Voronov E, et al. IL-1alpha and IL-1beta recruit different myeloid cells and promote different stages of sterile inflammation. J Immunol. 2011;187:4835–4843. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1102048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Terlizzi M, Molino A, Colarusso C, Donovan C, Imitazione P, Somma P, et al. Activation of the absent in melanoma 2 inflammasome in peripheral blood mononuclear cells from idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis patients leads to the release of pro-fibrotic mediators. Front Immunol. 2018;9:670. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Luheshi NM, Kovacs KJ, Lopez-Castejon G, Brough D, Denes A. Interleukin-1alpha expression precedes IL-1beta after ischemic brain injury and is localised to areas of focal neuronal loss and penumbral tissues. J Neuroinflammation. 2011;8:186. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-8-186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lamkanfi M, Dixit VM. Mechanisms and functions of inflammasomes. Cell. 2014;157:1013–1022. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Broz P, Dixit VM. Inflammasomes: mechanism of assembly, regulation and signalling. Nat Rev Immunol. 2016;16:407–420. doi: 10.1038/nri.2016.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sharif H, Wang L, Wang WL, Magupalli VG, Andreeva L, Qiao Q, et al. Structural mechanism for NEK7-licensed activation of NLRP3 inflammasome. Nature. 2019;570:338–343. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1295-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Stancu IC, Cremers N, Vanrusselt H, Couturier J, Vanoosthuyse A, Kessels S, et al. Aggregated Tau activates NLRP3-ASC inflammasome exacerbating exogenously seeded and non-exogenously seeded Tau pathology in vivo. Acta Neuropathol. 2019;137:599–617. doi: 10.1007/s00401-018-01957-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lu A, Magupalli VG, Ruan J, Yin Q, Atianand MK, Vos MR, et al. Unified polymerization mechanism for the assembly of ASC-dependent inflammasomes. Cell. 2014;156:1193–1206. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lu A, Li Y, Schmidt FI, Yin Q, Chen S, Fu TM, et al. Molecular basis of caspase-1 polymerization and its inhibition by a new capping mechanism. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2016;23:416–425. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.3199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wang LJ, Colella R, Yorke G, Roisen FJ. The ganglioside GM1 enhances microtubule networks and changes the morphology of Neuro-2a cells in vitro by altering the distribution of MAP2. Exp Neurol. 1996;139:1–11. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1996.0074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kamelgarn M, Chen J, Kuang L, Jin H, Kasarskis EJ, Zhu H. ALS mutations of FUS suppress protein translation and disrupt the regulation of nonsense-mediated decay. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018;115:E11904–E11913. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1810413115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Reddy PH, Manczak M, Yin X. Mitochondria-division inhibitor 1 protects against amyloid-beta induced mitochondrial fragmentation and synaptic damage in Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2017;58:147–162. doi: 10.3233/JAD-170051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.LePage KT, Dickey RW, Gerwick WH, Jester EL, Murray TF. On the use of neuro-2a neuroblastoma cells versus intact neurons in primary culture for neurotoxicity studies. Crit Rev Neurobiol. 2005;17:27–50. doi: 10.1615/critrevneurobiol.v17.i1.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.