Abstract

Objective

Narrow dentoalveolar ridges remain a serious challenge for the successful placement of dental implants. The aim of this study was to compare the clinical outcomes of piezosurgery versus surgical disc on ridge splitting in the atrophic edentulous maxilla.

Materials and Methods

This was a double-blinded randomized clinical trial. The healthy subjects who were candidates for maxillary ridge expansion were included in this experiment. Patients were randomly divided into two groups: piezosurgery group and surgical disc group. The width of the bone in the surgical site was measured by surgical calliper before the osteotomy. The bone width was remeasured after ridge-split completion (before suturing) and during the implant placement (4 months later). Then data were analysed by SPSS software, and the P value was set at 0.05.

Results

The study sample size included 20 cases. Our outcomes showed that both techniques (surgical disc and piezotome) were effective in ridge splitting (P < 0.001). However, the average bone width which was obtained after ridge splitting was significantly higher in the piezosurgery group (P < 0.05).

Conclusion

It can be concluded that both methods of piezosurgery and surgical disc can significantly lead to increase in the ridge width. However, the piezosurgery technique was more effective in ridge splitting.

Keywords: Ridge splitting, Atrophic maxillary ridge, Dental implant, Piezosurgery, Surgical disc

Introduction

Nowadays, the increased quality of life, the high therapeutic expectations and tendency to receive the most efficient treatments have made the use of novel medical and dental techniques inevitable [1–3]. It should be noted that a minimum thickness of 1–1.5 mm of bone should remain on both buccal and lingual/palatal aspects of the dental implants to ensure a successful treatment outcome [4–8].

Narrow and atrophic dentoalveolar ridges remain a serious challenge for the successful placement of dental implants [4–9]. Several techniques, such as guided bone regeneration, bone block grafting and ridge splitting may be applicable for bone expansion. However, the ridge-split procedure provides a quicker method in which an atrophic ridge can be predictably expanded and grafted, and it eliminates the need for a second surgical site harvesting [2, 4, 5, 7, 8, 10–12].

Several methods have been accomplished for the ridge-splitting procedure, manually with osteotomes or motor-driven devices like the surgical disc and saw [4–9, 13]. Recently, piezosurgery, that utilizes ultrasonic vibration to perform the accurate cutting, has been used for osteotomy and osteoplasty as well [2, 4, 5, 7, 8, 10–12, 14].

Regarding the importance and widespread application of diverse devices in the ridge expansion methods and the fact that there has been no clinical trial to evaluate and compare the mentioned techniques [4–8], we decided to compare the effects and clinical outcomes of piezosurgery and surgical disc on ridge splitting in the atrophic edentulous maxilla.

Materials and Methods

The experimental design of this study has been approved by the ethical committee of our university with the code of IR.mums.sd.REC1394.313.

The guidelines of Helsinki were followed in this study. Patients were informed that all their personal information remained classified and informed consents were obtained. All subjects accepted ridge splitting and implant placement. Moreover, all cases cooperated during all the stages of the experiment, and none encountered any complications.

This experiment was conducted in the oral and maxillofacial surgery department of Mashhad Dental School, Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Mashhad, Iran, between January 2018 and September 2018. It was a double-blinded randomized clinical trial in which the statistician and the patients were blind toward the design of the study.

The study sample size included 20 cases. The subjects with ASA Class I and II ASA systemic condition, who were candidates for maxillary ridge expansion and implant placement were included in this trial. They all had 2–4 mm of bone width in the treated maxillary region (which was confirmed by both pre-operative CBCT and clinical measurement). The absence of diabetes, systemic diseases and drug intake history affecting bone metabolism were the other inclusion criteria. The postoperative infection and wound dehiscence as well as lack of patient’s cooperation for follow-ups were our exclusion criteria.

Subjects were divided into two groups, namely piezosurgery and surgical disc groups randomly using a random number table. The width of bone in the surgical site was measured using a surgical calliper before the osteotomy. The surgical site was anesthetized using infiltration of lidocaine 2% with epinephrine 1/80,000 and a mucoperiosteal flap was created in the maxillary posterior region and then it was completely elevated. Afterwards, one incision was created on the crestal region of the edentulous ridge and two more were made on the mesial and distal of edentulous premolar region on the buccal side.

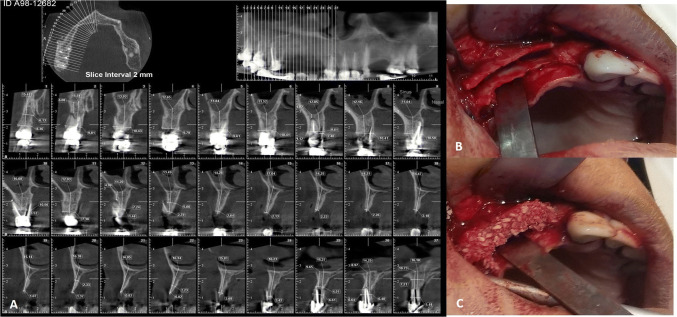

Then, the bone splitting was performed by an expert surgeon using either surgical disc (NSK Ltd, Tokyo, Japan) or Piezotome (Piezotome® Solo, Acteon, South Korea) in accordance with the patients’ group for the expansion of maxillary alveolar ridge in the posterior region. Consequently, the bone plates were split up using an osteotome and a surgical mallet. The space between these plates was filled with 500–1000 µm particles of Allograft Cenobone material (Tissue Regeneration Corporation Ltd, Kish, Iran), and the surgical site that underwent osteotomy was covered by Cenomembrane (Tissue Regeneration Corporation Ltd, Kish, Iran) (Fig 1).

Fig. 1.

Ridge splitting with piezosurgery. a Pre-operative CBCT view showed the atrophic maxillary ridge, b intraoperative clinical view of ridge splitting, C the clinical view of augmented ridge after splitting procedure

After scoring the periosteal flap and repositioning the mucoperiosteal flap for a tension-free primary closure, the surgical site was sutured using a 3.0 Vicril suture (Ethicon, Norderstedt, Germany). After surgical completion and prior to the flap suturing, the bone width was remeasured using the surgical calliper. It should be noted that the ethical committee of our university did not allow us to take extra CBCT (cone-beam CT scan) view from the patients. Therefore, it is not possible for the authors to use postoperative CBCT for study measurements.

All subjects received gelofen 400 mg (Iranpakhsh, Tehran, Iran) and amoxicillin 500 mg (Iranpakhsh, Tehran, Iran) every 8 h for 1 week postoperatively. Four months later, during placement of the implant, the width of bone in the region of the osteotomy was evaluated again.

In the present study, the predictor variable was the type of technique (pizotome vs. surgical disc) used for atrophic ridge splitting. The outcome variable was the bone width which was measured three times by the surgical calliper (before the surgery, immediately after the surgery and at the time implantation).

The data were analysed using t test, Friedman, ANOVA and Fisher’s exact tests. The calculations were performed utilizing SPSS 16 (SPSS, Chicago, IL) and the P value was set at 0.05.

Results

In this experiment, a total of 20 cases including 11 females (55%) and 9 males (45%) with the average age of 46.5 ± 8.4 ranging from 38 to 57 were studied.

The population was divided into two groups using a random number table and each group was dedicated to either ridge-splitting techniques (piezosurgery or surgical disc group). Fisher’s exact test showed that there was no significant difference in gender distribution between the studied groups (Table 1). Table 2 shows that the mean age had no difference between the groups, according to the independent t test.

Table 1.

Gender distribution in the studied groups (n = 20)

| Gender | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Female | Male | ||

| Groups | |||

| Piezosurgery | |||

| Number | 6 | 4 | 10 |

| Percent (%) | 60 | 40 | 100 |

| Surgical disc | |||

| Number | 5 | 5 | 10 |

| Percent (%) | 50 | 50 | 100 |

| Total | |||

| Number | 11 | 9 | 20 |

| Percent (%) | 55 | 45 | 100 |

| P value | 1 | ||

Table 2.

Comparison of the patients’ age in the studied groups (n = 20)

| Groups | Number | Mean ± SD | Age range | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Piezosurgery | 10 | 46.1 ± 6.49 | 38–56 | 0.666 |

| Surgical disc | 10 | 47.3 ± 5.74 | 40–57 |

The width of the edentulous maxillary region for each patient was measured three times clinically (before the ridge-splitting surgery, immediately after the surgery and at the time implantation).

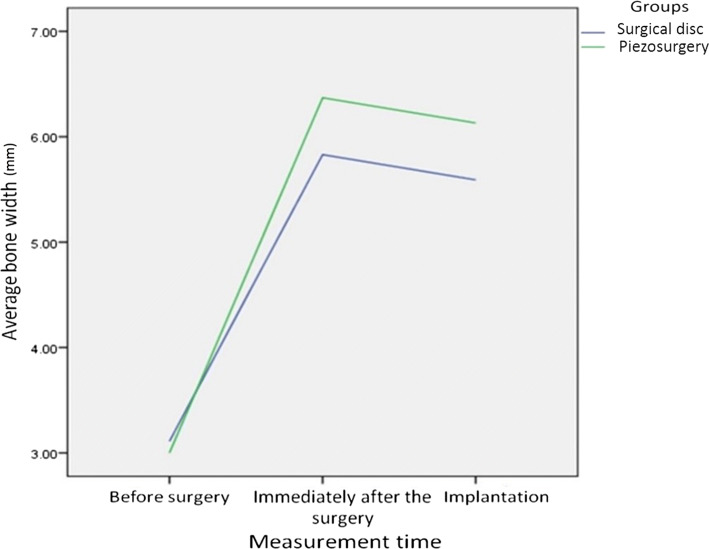

Table 3 illustrates the average bone width alterations at the studied times in surgical disc group. ANOVA test revealed that the average bone width on the second and third measurements had increased significantly compared to the first measurement (P < 0.001). Moreover, Table 4 shows the average bone width alterations at the studied times in the piezosurgery group. Friedman test indicated that the average bone width on the second and third measurements increased statistically compared to the first measurement (P < 0.001).

Table 3.

Comparison of the bone width average (mm) at the studied times in surgical disc group (n = 10)

| Time | N | Mean ± SD | The range | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-operatively | 10 | 3.11 ± 0.64 | 1.2–4.0 | < 0.001 |

| Immediately after the surgery | 10 | 5.83 ± 0.65 | 5.0–6.8 | |

| At the time of Implant placement (after 3 months) | 10 | 5.59 ± 0.64 | 4.7–6.6 |

Table 4.

Comparison of the bone width average (mm) at the studied times in piezosurgery group (n = 10)

| Time | N | Mean ± SD | The range | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-operatively | 10 | 3.0 ± 0.44 | 2.2–3.5 | < 0.001 |

| Immediately after the surgery | 10 | 6.37 ± 0.51 | 5.8–6.1 | |

| At the time of Implant placement (after 3 months) | 10 | 6.13 ± 0.42 | 5.7–6.8 |

As demonstrated in Table 5, although the pre-operative average bone width was a bit higher in surgical disc group, compared to pizotome group, the difference was not significant (P = 0.660). The average bone width obtained after ridge-splitting procedure and at the time of implantation was significantly higher in the piezosurgery group (P = 0.044 and 0.039, respectively). The above-mentioned information is clearly illustrated in Fig. 2.

Table 5.

Comparison of the average bone width (mm) between the experimental groups at the studied times (n = 20)

| Groups | Before surgery | Immediately after surgery | At the time of implantation (3 months later) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Surgical Saw | 3.11 ± 0.64 | 5.83 ± 0.65 | 5.59 ± 0.64 |

| Piezosurgery | 3.0 ± 0.44 | 6.37 ± 0.51 | 6.13 ± 0.42 |

| P value | 0.660* | 0.044** | 0.039* |

*Independent t test;** Mann–Whitney U test

Fig. 2.

Diagram of bone width differences between the experimental groups at the studied times following ridge-splitting technique

The successful implant osseointegration was observed in all cases, both clinically and radiographically without any complications.

Discussion

The purpose of this clinical study was the evaluation of ridge-splitting success using piezosurgery compared with the conventional surgical disc.

Given the increasing use of piezosurgery in many areas of oral and maxillofacial surgery and its widely reported protective effects [3, 9, 15, 16], an objective evaluation of this technique in the pre-implant ridge expansion surgery is warranted.

Narrow edentulous ridges less than 5 mm width present a challenge to the clinician for implant placement; hence, lateral bone augmentation procedures are necessary. These procedures involve the use of bone grafting techniques (with different types of grafts such as autografts, allografts, xenografts, or bone substitutes) and guided bone regeneration (GBR) per se or in combination with grafting procedures as well as the use of ridge expansion techniques such as split ridge osteotomy and horizontal distraction osteogenesis [4, 5, 12, 13, 17].

The ridge-split procedure represents one form of augmentation technique for narrow ridges. The procedure can be used for simultaneous placement of implants in addition to ridge expansion, thus reducing the overall time for implant therapy [2, 4–6, 8, 10–12].

Ridge splitting for root-form implant placement was developed in the 1970s by Dr. Hilt Tatum [18].

The split technique is an advantageous bone augmentation technique as it provides a shorter treatment period in comparison with conventional bone graft techniques, and it does not require a waiting period of 4–6 months for bone consolidation prior to implant placement [4, 5, 12, 13, 17].

In a study, Stricker et al. [5] introduced piezosurgery for the treatment of atrophic jaws. This technique could be implemented simultaneously with the insertion of implants in one session [4]. However, it may be performed in a two-step fashion [4].

This method creates a sagittal osteotomy of the edentulous ridge using instruments such as chisels between the two cortical plates to expand the ridge width and consequently allows the placement of implants [4–9].

In addition, ridge splitting decreases the morbidity since it avoids a second surgical donor site for bone harvesting. However, this procedure can only increase the buccolingual bone dimension and is not applicable if there is insufficient bone height for implant placement [2, 4, 5, 7, 8, 10–12].

Ridge-split augmentation aims at the creation of a new implant bed by longitudinal osteotomy of the alveolar ridge. As a result, the adequate bone height for implant placement should exist as the splitting of the crest will not increase the bone volume vertically [1, 8, 10, 11, 19]. A minimum of 3 mm of bone width, including at least 1 mm of cancellous bone, is desired to insert a chisel between cortical plates and consequently expand the cortical bones [8, 19].

As a matter of fact, implementing the technique on atrophic ridges less than 3.0 mm wide may result in unfavourable bone fractures that lead to bone resorption [11, 17].

This method is more applicable for maxilla than mandible. The thinner cortical plates and softer medullary bone make the maxillary ridge easier to expand [4, 8, 9, 14, 17]. Hence, the authors selected atrophic maxillary ridge in this experiment.

Different surgical techniques have been employed for ridge splitting, up to now [4–9, 13]. Suh et al. [13] described the microsaw and disc technique which provides better control in preparing a cut along a narrow alveolar ridge and it appears less traumatic to the bone. Additionally, less bone is lost, since the microsaw and disc method creates much thinner cuts compared to conventional burs [17].

Piezosurgery, that utilizes ultrasonic vibration which allows clean cutting with precise incisions, is a relatively new technique for osteotomy and osteoplasty [6, 19].

Advantages of piezoelectric ultrasonic surgical instruments are the precise and accurate micrometric bone cuts as well as clear surgical fields without soft tissue damage [3, 8, 9, 17].

Ultrasonic vibrations have been used to cut tissue for three decades in oral and maxillofacial surgery [19]. Peizosurgery was used to minimize surgical trauma and preserve the cortices for support, and it serve as a source of osteocytes for appropriate osseointegration of the implants [7, 15, 19, 20].

Our study outcomes depicted that both techniques (surgical disc and piezotome) were effective in ridge-splitting procedure (P < 0.001). It should be noteworthy that the piezosurgery and the disc are both devices to split the bone not expand the ridge. However, the average bone width obtained after ridge-splitting surgery and at the time of implant placement was significantly higher in piezosurgery group (P < 0.05).

These results were in line with the articles which reported the success of piezosurgery in oral and maxillofacial surgeries such as cranioplasty and orthognathic surgeries [9, 15, 16].

A meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies (RCT) by Jiang et al. [20] showed that the piezosurgery method, compared to those with rotating instruments, takes longer to conduct but associates with less postoperative complications.

Although CBCT is considered, the standard of care today when taking up cases for implant placement especially where augmentation is required [4–9, 13]. It should be noted that the ethical committee of our university did not allow us to take extra cone-beam CT scan (CBCT) view from the patients. Therefore, it is not possible for the authors to use postoperative CBCT for study measurements.

The ridge-split technique for the maxillary narrow alveolar ridge provides predictable results in relation to primary stability and implant surveillance. This technique avoids morbidity related to the harvesting of autologous bone graft and provides a stable widening of the alveolar crest [3, 4, 8].

Although the practitioner’s expertise and experience play a major role in the successful long-lasting implant placement, the evaluation of various anatomical factors, such as bone density in the edentulous region, influence the determination of number, size and position of the implants to reach the best results [4, 6, 8, 9].

Conclusion

It can be concluded that both ridge-splitting methods using piezosurgery and surgical disc can significantly lead to increase in ridge width. The piezosurgery and the disc are both devices to split the bone not expand the ridge. However, the piezosurgery technique was more effective in ridge splitting clinically.

Limitations and Suggestions

Further clinical trial studies with larger sample sizes should be considered in future experiments to evaluate the relevance of our findings clinically.

Acknowledgements

The authors appreciate the continued support of the research counsellor of Mashhad University of medical sciences, Mashhad, Iran. The data were extracted from the undergraduated Thesis No. 2984.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest in this study.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in this study involving the human participant were in accordance with the ethical standards of our institutional research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The experimental design of this study has been approved by the Ethical Committee of Mashhad University of Medical Sciences with the code of IR.mums.sd.REC1394.313.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Bassetti MA, Bassetti RG, Bosshardt DD. The alveolar ridge splitting/expansion technique: a systematic review. Clin Oral Implant Res. 2016;27(3):310–324. doi: 10.1111/clr.12537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zakhary IE, El-Mekkawi HA, Elsalanty ME. Alveolar ridge augmentation for implant fixation: status review. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2012;114(5):179–189. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2011.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Samieirad S, Soofizadeh R, Shokouhifar A, Mianbandi V. A two-step method for the preparation of implant recipient site in severe atrophic maxilla: a case report of the alveolar ridge split technique followed by bone expansion. J Dent Mater Tech. 2018;8:10–20. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moro A, Gasparini G, Foresta E, Saponaro G, Falchi M, Cardarelli L, et al. Alveolar ridge split technique using piezosurgery with specially designed tips. Biomed Res Int. 2017;17:1–8. doi: 10.1155/2017/4530378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stricker A, Stübinger S, Voss P, Duttenhöfer F, Fleiner J. The bone splitting stabilisation technique—a modified approach to prevent bone resorption of the buccal wall. Oral Health Dent Manag. 2014;13(3):870–876. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pereira CCS, Gealh WC, Meorin-Nogueira L, Garcia-Júnior IR, Okamoto R. Piezosurgery applied to implant dentistry: clinical and biological aspects. J Oral Implantol. 2014;40(S1):401–408. doi: 10.1563/AAID-JOI-D-11-00196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kelly A, Flanagan D. Ridge expansion and immediate placement with piezosurgery and screw expanders in atrophic maxillary sites: two case reports. J Oral Implantol. 2013;39(1):85–90. doi: 10.1563/AAID-JOI-D-11-00124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Agrawal D, Gupta AS, Newaskar V, Gupta A, Garg S, Jain D. Narrow ridge management with ridge splitting with piezotome for implant placement: report of 2 cases. J Indian Prosthodont Soc. 2014;14(3):305–309. doi: 10.1007/s13191-012-0216-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pavlíková G, Foltán R, Horká M, Hanzelka T, Borunská H, Šedý J. Piezosurgery in oral and maxillofacial surgery. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2011;40(5):451–457. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2010.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.González-García R, Monje F, Moreno C. Alveolar split osteotomy for the treatment of the severe narrow ridge maxillary atrophy: a modified technique. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2011;40(1):57–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2010.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Demetriades N, Park JI, Laskarides C. Alternative bone expansion technique for implant placement in atrophic edentulous maxilla and mandible. J Oral Implantol. 2011;37(4):463–471. doi: 10.1563/AAID-JOI-D-10-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sohn D-S, Lee H-J, Heo J-U, Moon J-W, Park I-S, Romanos GE. Immediate and delayed lateral ridge expansion technique in the atrophic posterior mandibular ridge. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010;68(9):2283–2290. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2010.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Suh J-J, Shelemay A, Choi S-H, Chai J-K. Alveolar ridge splitting: a new microsaw technique. Int J Periodont Restor Dent. 2005;25(2):209–214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Han JY, Shin SI, Herr Y, Kwon YH, Chung JH. The effects of bone grafting material and a collagen membrane in the ridge splitting technique: an experimental study in dogs. Clin Oral Implant Res. 2011;22(12):1391–1398. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0501.2010.02127.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martini M, Röhrig A, Reich RH, Messing-Jünger M. Comparison between piezosurgery and conventional osteotomy in cranioplasty with fronto-orbital advancement. J Cranio Maxillofac Surg. 2017;45(3):395–400. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2016.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Spinelli G, Lazzeri D, Conti M, Agostini T, Mannelli G. Comparison of piezosurgery and traditional saw in bimaxillary orthognathic surgery. J Cranio Maxillofac Surg. 2014;42(7):1211–1220. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2014.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kheur M, Gokhale S, Sumanth S, Jambekar S. Staged ridge splitting technique for horizontal expansion in mandible: a case report. J Oral Implantol. 2014;40(4):479–483. doi: 10.1563/AAID-JOI-D-12-00068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tatum JH. Maxillary and sinus implant reconstructions. Dent Clin North Am. 1986;30(2):207–229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aly LAA. Piezoelectric surgery: applications in oral and maxillofacial surgery. Fut Dent J. 2018;14(2):129–136. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jiang Q, Qiu Y, Yang C, Yang J, Chen M, Zhang Z. Piezoelectric versus conventional rotary techniques for impacted third molar extraction: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Medicine. 2015;94(41):23–34. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000001685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]