To survive, animals must process aversive or stressful events quickly, and evaluate and store the related information. Accumulating neural circuity studies have identified key brain nuclei, such as the amygdala, lateral habenula (LHb), periaqueductal grey (PAG), ventromedial hypothalamic nucleus, hippocampus, among others, in the processing of negative experiences [1, 2]. Yet more work is needed to determine how these brain structures coordinate with each other in coping with such experiences.

A recent study published in Science entitled “Median raphe controls acquisition of negative experience in the mouse” from Dr. Nyiri’s group at the Hungarian Academy of Sciences sheds new light on this complex and important question [3]. Using cell-type-specific neuronal tracing, block-face scanning immunoelectron microscopy, in vivo and in vitro electrophysiology, and optogenetic and chemogenetic manipulations together with behavioral tasks, they revealed that the median raphe region (MRR, also named median raphe nucleus, MnR), especially the vesicular glutamate transporter 2 (vGluT2)-positive neurons in the MRR may serve as a key hub for the coordination of negative experience processing.

While the serotoninergic neurons in the MRR have been investigated, Szőnyi et al. studied a previously neglected neuron type – vGluT2-neurons. These constitute at least 20% of all MRR neurons, and are distributed both in the median and the paramedian parts of the region. Using multichannel recording and optogenetic tagging, they showed that MRR vGluT2-neurons respond selectively to an aversive stimulus (air puffs) and to a much lesser extent to mildly aversive light-emitting diode flashes, while they do not respond to the rewarding stimulus of water drops.

Three groups of functional experiments were carried out to decipher the roles of MRR vGluT2-neurons in negative experience. First, acute in vivo optogenetic somatic activation of these neurons caused significant real-time place aversion and conditioned place aversion, and a decrease in nose-pokes for food pallet rewards in hungry mice after pairing. Second, in vivo chemogenetic activation of the soma of the neurons led to highly aggressive behavior in a social interaction test and the resident-intruder test. Moreover, chronic chemogenetic activation of somata for 3 weeks induced anhedonia in the sucrose preference test. Third, the optogenetic activation of the MRR vGluT2-neurons triggered movement of the mice as well as hippocampal theta oscillations. In a loss-of-function study using a delay-cued fear conditioning paradigm, optogenetic inhibition of these neurons during the presentation of adverse stimuli decreased contextual freezing behavior and generalized conditioned fear, showing their essential role in storing the memory of a negative experience.

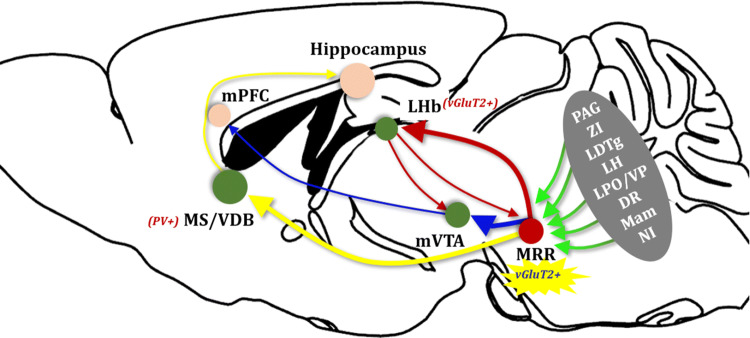

Szőnyi et al. reached the conclusion that “MRR controls acquisition of negative experience in the mouse” based not only on the above functional data but also their solid and detailed tracing of the inputs and outputs of MRR vGluT2-neurons. It is worth pointing out that the use of block-face scanning immunoelectron microscopy to demonstrate the details of the synapses formed by MRR vGluT2-neurons with their downstream targets is a highlight. As shown in Figure 1 (green lines), MRR vGluT2-neurons receive extensive inputs from aversion-, defense- and memory-related areas including the PAG, zona incerta, laterodorsal tegmental nucleus, lateral hypothalamus, lateral preoptic area and ventral pallidum, dorsal raphe, mammillary complex, and nucleus incertus. In the downstream tracing of MRR vGluT2-neurons, three structures were intensively studied: the LHb, medial ventral tegmental nucleus (mVTA), and medial septum/vertical limb of the diagonal band of Broca (MS/VDB). First, using double-injection of tracers, they found that MRR vGluT2-neurons establish glia-enwrapped synapses on LHb vGluT2-neurons, which then project to the mVTA. The vGluT2-positive MRR neurons and the vGluT2-positive LHb neurons projecting to the MRR also form direct reciprocal connections (Fig. 1, red lines). Second, MRR vGluT2-neurons directly innervate neurons in the mVTA that project to the medial prefrontal cortex (Fig. 1, blue lines). Third, MRR vGluT2-neurons also directly innervate parvalbumin-positive neurons in the MS/VDB that project to the hippocampus (Fig. 1, yellow lines). These anatomical tracing data provide structural rationales for the functional experiments and elaborate on the role of the MRR as a key hub for the acquisition of negative experience.

Fig. 1.

The median raphe region (MRR) is a lower-brainstem structure that coordinates the acquisition of negative experience. MRR vGluT2-neurons receive extensive inputs from negative experience-related regions and coordinate negative experience processing via three key pathways: MRR–LHb, MRR–mVTA, and MRR–MS/VDB (MRR median raphe region, vGluT2 vesicular glutamate transporter 2, LHb lateral habenula, mVTA medial ventral tegmental nucleus, MS/VDB medial septum and vertical limb of the diagonal band of Broca, PV parvalbumin, mPFC medial prefrontal cortex, PAG periaqueductal gray, ZI zona incerta, LDTg laterodorsal tegmental nucleus, LH lateral hypothalamus, LPO/VP lateral preoptic area and ventral pallidum, DR dorsal raphe, Mam mammillary complex, NI nucleus incertus).

Exploring the question of negative experience coordination is no doubt very challenging considering the scope of “negative experience” and its complex processes [1, 4–8]. Negative experience in this study alone incorporates behavioral concepts that include active avoidance, conditioned fear, aggression, and depression. The related coordination includes at least the recognition of aversive/alerting signals, the production of quick and adequate behavioral responses, and the possible learning procedures [9, 10]. It is exciting to see in this article the identification of a new group of functional neurons in the MRR and their roles in the acquisition of negative experience along with detailed anatomical support.

In the field of the neural circuity underlying negative experience processing, the idea that one structure in the brainstem can coordinate the activities of several upstream convergent inputs and several downstream outputs simultaneously is intriguing. The detailed mechanism of the coordination, especially at different time scales (acute aversion and long-term hippocampal memory encoding), would help in the understanding of neuronal information processing in general and even in neurocomputation.

Psychiatric disorders present a unique and enormous challenge. Disorders such as depression and post-traumatic stress disorder are proposed to result from neural circuit disruption. Accumulating evidence has shown the involvement of the MRR in anxiety and other psycho-behavioral states [1]. The detailed anatomical structure of the inputs/outputs of MRR vGluT2-neurons and their physiological functions provide a rational basis for future studies: to investigate the connection between malfunction in this key hub and negative experience-related mood disorders, which might suggest new therapies.

Acknowledgements:

This research highlight article was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31971072 and 81671444), Guangdong International Cooperation Grant (2019A050510032), Shenzhen Science and Technology Innovation Committee Fund (JCYJ20180508152336419), and Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of Brain Connectome and Behavior (2017B030301017).

Conflict of interest

The author declares no competing interest.

References

- 1.Gross CT, Canteras NS. The many paths to fear. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2012;13:651–658. doi: 10.1038/nrn3301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang L, Chen IZ, Lin D. Collateral pathways from the ventromedial hypothalamus mediate defensive behaviors. Neuron. 2015;85:1344–1358. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.12.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Szőnyi A, Zichó K, Barth AM, Gönczi RT, Schlingloff D, Török B, et al. Median raphe controls acquisition of negative experience in the mouse. Science. 2019;366:eaay8746. doi: 10.1126/science.aay8746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cao X, Li LP, Wang Q, Wu Q, Hu HH, Zhang M, et al. Astrocyte-derived ATP modulates depressive-like behaviors. Nat Med. 2013;19:773–777. doi: 10.1038/nm.3162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cui Y, Yang Y, Ni Z, Dong Y, Cai G, Foncelle A, et al. Astroglial Kir4.1 in the lateral habenula drives neuronal bursts in depression. Nature. 2018;554:323–327. doi: 10.1038/nature25752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li L, Feng X, Zhou Z, Zhang H, Shi Q, Lei Z, et al. Stress accelerates defensive responses to looming in mice and involves a locus coeruleus-superior colliculus projection. Curr Biol. 2018;28(859–871):e855. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2018.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li Y, Zeng J, Zhang J, Yue C, Zhong W, Liu Z, et al. Hypothalamic circuits for predation and evasion. Neuron. 2018;97(911–924):e915. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2018.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang H, Yang J, Xi W, Hao S, Luo B, He X, et al. Laterodorsal tegmentum interneuron subtypes oppositely regulate olfactory cue-induced innate fear. Nat Neurosci. 2016;19:283–289. doi: 10.1038/nn.4208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Luo H, Liu Z, Liu B, Li H, Yang Y, Xu ZD. Virus-mediated overexpression of ETS-1 in the ventral hippocampus counteracts depression-like behaviors in rats. Neurosci Bull. 2019;35:1035–1044. doi: 10.1007/s12264-019-00412-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tang N, Ding YF, Zhang W, Hu J, Xu XH. Stay active to cope with fear: a cortico-intrathalamic pathway for conditioned flight behavior. Neurosci Bull. 2019;35:1116–1119. doi: 10.1007/s12264-019-00439-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]