Abstract

Objective

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a chronic inflammatory skin disease that is complicated by an increased risk for skin and systemic infections. Preventive therapy for AD is based on skin barrier improvement and anti-inflammatory treatments, whereas overt skin and systemic infections require antibiotics or antiviral treatments. This review updates the pathophysiology, diagnosis, management, controversy of antibiotic use, and potential treatments of infectious complications of AD.

Data Sources

Published literature obtained through PubMed database searches and clinical pictures.

Study Selections

Studies relevant to the mechanisms, diagnosis, management, and potential therapy of infectious complications of AD.

Results

Skin barrier defects, type 2 inflammation, Staphylococcusaureus colonization, and cutaneous dysbiosis are the major predisposing factors for the increased infections in AD. Although overt infections require antibiotics, the use of antibiotics in AD exacerbation remains controversial.

Conclusion

Infectious complications are a comorbidity of AD. Although not common, systemic bacterial infections and eczema herpeticum can be life-threatening. Preventive therapy of infections in AD emphasizes skin barrier improvement and anti-inflammatory therapy. The use of antibiotics in AD exacerbation requires further studies.

Key Messages.

-

•

Factors that contribute to the increased infections in atopic dermatitis (AD) are skin barrier defects, suppression of cutaneous innate immunity by type 2 inflammation, Staphylococcus aureus colonization, and cutaneous dysbiosis.

-

•

Skin infections in AD increase the risk of life-threatening systemic infections.

-

•

The use of antibiotics for AD exacerbation remains controversial, and further studies are needed to define which subsets of these patients can benefit from antibiotics.

-

•

The goals of infection prevention in AD consist of skin barrier improvement, anti-inflammatory therapy, and minimizing the use of antibiotics.

Instructions.

Credit can now be obtained, free for a limited time, by reading the review article and completing all activity components. Please note the instructions listed below:

-

•

Review the target audience, learning objectives and all disclosures.

-

•

Complete the pre-test.

-

•

Read the article and reflect on all content as to how it may be applicable to your practice.

-

•

Complete the post-test/evaluation and claim credit earned. At this time, physicians will have earned up to 1.0 AMA PRA Category 1 Credit TM . Minimum passing score on the post-test is 70%.

Overall Purpose

Participants will be able to demonstrate increased knowledge of the clinical treatment of allergy/asthma/immunology and how new information can be applied to their own practices.

Learning Objectives

At the conclusion of this activity, participants should be able to:

-

•

Describe the mechanisms that lead to increased infections in atopic dermatitis (AD).

-

•

Discuss the strategies for infection prevention in AD.

Release Date: January 1, 2021

Expiration Date: December 31, 2022

Target Audience

Physicians involved in providing patient care in the field of allergy/asthma/immunology

Accreditation

The American College of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology (ACAAI) is accredited by the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME) to provide continuing medical education for physicians.

Designation

The American College of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology (ACAAI) designates this journal-based CME activity for a maximum of 1.0 AMA PRA Category 1 Credit TM. Physicians should claim only the credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity.

Disclosure Policy

As required by the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME) and in accordance with the American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology (ACAAI) policy, all CME planners, presenters, moderators, authors, reviewers, and other individuals in a position to control and/or influence the content of an activity must disclose all relevant financial relationships with any commercial interest that have occurred within the past 12 months. All identified conflicts of interest must be resolved, and the educational content thoroughly vetted for fair balance, scientific objectivity, and appropriateness of patient care recommendations. It is required that disclosure be provided to the learners prior to the start of the activity. Individuals with no relevant financial relationships must also inform the learners that no relevant financial relationships exist. Learners must also be informed when off-label, experimental/investigational uses of drugs or devices are discussed in an educational activity or included in related materials. Disclosure in no way implies that the information presented is biased or of lesser quality. It is incumbent upon course participants to be aware of these factors in interpreting the program contents and evaluating recommendations. Moreover, expressed views do not necessarily reflect the opinions of ACAAI.

Disclosure of Relevant Financial Relationships

All identified conflicts of interest have been resolved. Any unapproved/investigative uses of therapeutic agents/devices discussed are appropriately noted.

Planning Committee

-

•

Larry Borish, MD, Consultant, Fees/Contracted Research: AstraZeneca, Novartis, Regeneron, Teva

-

•

Mariana C. Castells, MD, PhD, has no relevant financial relationships to disclose

-

•

Anne K. Ellis, MD, MSc, Advisory Board/Speaker, Honorarium: Alk-Abello, Aralez, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Circassia Ltd., GlaxoSmithKline, Meda, Merck, Novartis, Pediapharma, Pfizer, Sanofi, Takeda; Research, Grants: Bayer, Circassia Ltd., Green Cross Pharmaceuticals, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, Sanofi, Sun Pharma

-

•

Mitchell Grayson, MD, Advisory Board, Honorarium: AstraZeneca, Genentech, Novartis

-

•

Matthew Greenhawt, MD, Advisory Board/Consultant/Speaker, Fees/Honorarium: Allergenis, Aquestive, DVB Technologies, Genentech, Intrommune, Kaleo, Nutricia, Sanofi/Genzyme

-

•

William Johnson, MD, has no relevant financial relationships to disclosure

-

•

Donald Leung, MD, Chair, DSMC/ Consultant, Fees: AbbVie, Aimmune, Regeneron, Sanofi-Aventis Pharma; Research, Grants: Incyte Corp, Pfizer

-

•

Jay Lieberman, MD, Advisory Board/Author/Speaker, Honorarium/Contracted Research: Aimmune, ALK-Abello, Aquestive Therapeutics, DBV Technologies

-

•

Gailen D. Marshall, Jr, MD, PhD, has no relevant financial relationships to disclose

-

•

Anna Nowak-Wegrzyn, MD, Chair, Honorarium/Contracted Research: Alk-Abello, Merck; Consultant, Fees: LabCorp; Co-Investigator, Fees: Sanofi Aventis; Private Investigator, Contracted Research/Honorarium: Abbott, Astellas Pharma, Danone Nutricia, DBV Technologies, Nestle

-

•

John J. Oppenheimer, MD, Consultant, Fees: DBV Technologies, GlaxoSmithKline, Sanofi, Teva; Adjudication, Fees: MedImmune

-

•

Jonathan M. Spergel, MD, PhD, Advisory Board/Consultant/Research, Fees/Contracted Research/Honorarium: Aimmune Therapeutics, DBV Technologies, Regeneron, Pfizer; Speaker, Honorarium: Abbott

Authors

-

•

Vivian Wang, MD, has no relevant financial relationships to disclose.

-

•

Juri Boguniewicz, MD, has no relevant financial relationships to disclose.

-

•

Mark Boguniewicz, MD, has no relevant financial relationships to disclose.

-

•

Peck Y. Ong, MD, has no relevant financial relationship to disclose.

Recognition of Commercial Support: This activity has not received external commercial support.

Copyright Statement: ©2015-2021 ACAAI. All rights reserved.

CME Inquiries: Contact the American College of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology at education@acaai.org or 847-427-1200.

Introduction

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is the most common chronic inflammatory skin disease that affects both children and adults with a prevalence of up to 18% and 7%, respectively. Patients with AD and their caregivers experience decreased quality of life, including disruption in daily activities at school and at work, sleep disturbance, depression, and anxiety.1 In addition to these complications, patients with AD are at increased risk for infections.2 The prevalence of cutaneous and systemic infections in patients with AD is significantly higher than those without AD.3 Infectious complications of AD include skin and soft tissue infections (SSTI), eczema herpeticum (EH), bacteremia, osteomyelitis, septic arthritis, and endocarditis.4 These complications lead to significant financial burden on the health care system.5 In this review, we will summarize the advances in the mechanisms, clinical complications, and management of infections in AD.

What Causes an Increase in Infections in AD?

Skin Barrier Defects

AD is inherently associated with skin barrier defects, as measured by transepidermal water loss.6 Patients with AD have a significantly thinner stratum corneum owing to a lack of terminal keratinocyte differentiation. As a result of skin barrier abnormalities, AD is associated with increased transepidermal water loss, which is greatest in the patients with most severe AD.2 The molecular basis for skin barrier defects is due to a deficiency in proteins and lipids with barrier functions including filaggrin, involucrin, claudins, ceramides, cholesterol, and free fatty acids.7 The filaggrin gene loss-of-function (FLG LoF) was the first evidence for the genetic basis of skin barrier defects in AD.2 FLG LoF leads to decreased skin hydration and renders AD susceptible to environmental insults including allergens and pathogens.2 In healthy skin, filaggrin is broken down into hygroscopic amino acids, including urocanic acid and pyrrolidone carboxylic acid, which maintain the acidic pH of the stratum corneum. The acidic environment in healthy skin decreases the expression of 2 staphylococcal surface proteins, clumping factor B and fibronectin-binding protein, which bind to host proteins cytokeratin 10 and fibronectin, respectively.2 Defects in filaggrin expression lead to decreased urocanic acid and pyrrolidone carboxylic acid levels and a rise in pH, which favors Staphylococcus aureus proliferation.8 FLG LoF is associated with early-onset AD and is present in approximately 25% to 30% of patients with AD of European and Asian descent.9 A more recent study using a newer sequencing method (massively parallel sequencing) also found a relatively high prevalence (15.3%) of FLG LoF among African American children with AD.10 This prevalence is significantly higher than the 5.8% that was previously reported.10 Patients with AD with FLG LoF had a 7-times higher risk of having 4 or more episodes of skin infections requiring antibiotics within 1 year than patients with AD without FLG LoF.2 FLG LoF also confers a significantly higher risk for EH in patients with AD.2 Lipids in the stratum corneum of patients with AD have been found to differ substantially in composition from those of healthy individuals. Patients with AD have decreased expression of fatty acid elongases that contribute to observed changes in skin lipids and interleukin (IL)-4 and IL-13, having an inhibitory effect on these enzymes.11 In addition to physical barrier defects, AD is also known to have a deficient chemical barrier that comprises innate defense molecules including β-defensin 2 and cathelicidin.2

Immune Dysregulation

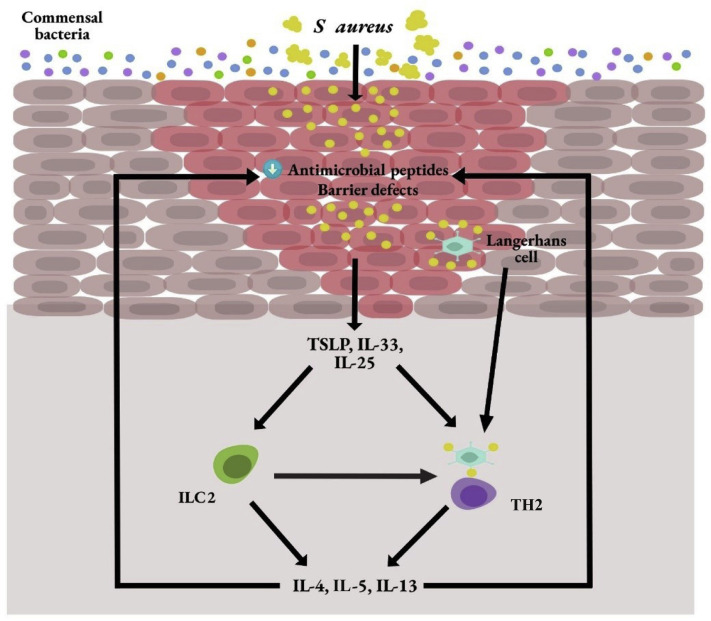

Keratinocytes are skin epithelial cells that contribute to the barrier functions and immune response. In patients with AD, keratinocytes produce an increased amount of thymic stromal lymphopoietin, IL-33, and IL-25,2 which activate innate lymphoid cells 2 (ILC2) to produce type 2 cytokines, including IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13.12 IL-4 and IL-13 have been indicated to suppress keratinocyte expression of antimicrobial peptides and skin barrier functions,11 , 13 thus predisposing patients with AD to have increased skin infections. In addition to keratinocytes, endothelial cells, macrophages, mast cells, and basophils are other cellular sources of IL-33.12 , 14 IL-33 is stored preformed in the nucleus of these cells and produced readily to exert its inflammatory effects.12 It attaches to its receptor (ST2) on ILC2 to activate the production of IL-5 and IL-13.2 IL-25 acts on both ILC2 and T cells by attaching to its receptor, IL-17RB.12 , 15 In combination with IL-33 and thymic stromal lymphopoietin, it enhances the proliferation and cytokine expression by ILC2.12 Both IL-33 and IL-25 are highly expressed in AD lesions.2

Defects in dendritic cells also contribute to increased infections in AD. Both myeloid and plasmacytoid dendritic cells in patients with AD produced significantly less interferon-α.2 Toll-like receptor-2 (TLR-2)-sensing of S aureus by Langerhans cells and inflammatory dendritic epidermal cells has also been found to be impaired in patients with AD.16 Natural killer cells have recently been found to be deficient in patients with AD.17 This deficiency may also contribute to increased type 2 inflammation owing to a potential counter-regulatory mechanism between the natural killer cells and type 2 inflammation.17

Staphyloccocus aureus Colonization

Up to 90% of patients with AD are colonized with S aureus.2 This predominance of S aureus is unique to AD, as compared with healthy individuals and patients with another chronic inflammatory skin disease, psoriasis.18 The predominance of S aureus in AD may be attributed to the virulence factors of this bacteria and its ability to evade the cutaneous immunity of patients with AD. S aureus fibronectin has a special affinity for type 2 inflammation.19 In addition, S aureus produces enterotoxins (superantigens) that are known to break down the skin barrier and enhance type 2 inflammation.19 Superantigens also down-regulate the cutaneous production of interferon-γ and tumor necrosis factor-α, both of which are important mediators of cellular immunity against bacterial and viral infections.20 Methicillin-resistant S aureus (MRSA) has been found to produce significantly more superantigens than methicillin-sensitive S aureus (MSSA).2 Both superantigens and another staphylococcal toxin, the α toxin, may contribute to keratinocyte apoptosis and barrier defects in AD.2 , 21 Staphylococcal δ toxin may also contribute to AD inflammation by inducing mast cell degranulation.19

Dysbiosis of Skin Flora

The maintenance of healthy skin also depends on its commensal microbiome. Normal skin flora is found beyond the surface of the epithelium, which highlights the protective role in immune defense and regulation.22 The most abundant microbes consists of Cutibacterium acnes (formerly known as Propionibacterium acnes), Corynebacterium , and coagulase-negative Staphylococcus (CoNS).22 Patients with AD are deficient in commensal bacteria,22 and this facilitates the virulence of S aureus in lesional skin (Fig 1 ). The roles of commensal bacteria are 2-fold as follows: (1) their ability to modulate the host immune system to minimize inflammation and to increase protection against microbial pathogens; (2) their ability to directly outcompete microbial pathogens such as S aureus. CoNS, S epidermidis, was found to produce a lipoitechoic acid that is capable of preventing injury-induced TLR-3–mediated cutaneous inflammation by means of TLR-2 interaction.22 S epidermidis also modulates host cytotoxic and regulatory T cells in wound repair and immune tolerance, respectively.22 In addition to its anti-inflammatory role, S epidermidis may also up-regulate antimicrobial peptide production by keratinocytes to protect against microbial pathogens.22 CoNS including S epidermidis, S lugdunensis, and S hominis are capable of producing proteases or antimicrobial factors that either prevent biofilm formation by S aureus or are bactericidal against it.22

Figure 1.

Dysbiosis and immune dysregulation of atopic dermatitis. IL, interleukin; ILC2, innate lymphoid cells 2; S aureus, Staphylococcus aureus; TH2, T-helper cells type 2; TSLP, thymic stromal lymphopoietin.

Bacterial Infections

Impetigo, cellulitis, and skin abscesses are common SSTIs in AD. The most common cause of these infections is S aureus. Impetigo typically presents with oozing serum that has dried up, giving it a honey-crusted appearance surrounded by an erythematous base (Fig 2 ). Impetigenous lesions may also present with fluid-filled blisters (bullous impetigo), which may be mistaken for EH. Nonpurulent SSTIs include erysipelas and cellulitis. These infections usually start in a focal skin area but may spread rapidly to cover the major parts of the body such as the arms, legs, trunk, or face.23 Focal erythema, swelling, warmth, and tenderness are signs of these infections. These patients may experience fever and bacteremia. Purulent SSTI presents as skin abscesses, which may be fluctuant or nonfluctuant nodules or pustules surrounded by an erythematous swelling. The lesions may be tender and warm. MRSA is a common cause of these lesions. In addition, SSTI in patients with AD may lead to systemic complications, which include bacteremia, osteomyelitis, septic arthritis or bursitis, and, more rarely, endocarditis and staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome, which is mediated by staphylococcal toxins. Persistent fever and specific signs—including an ill-looking appearance, lethargy (bacteremia), focal point tenderness of the bone (osteomyelitis), joint swelling (septic arthritis/bursitis), heart murmur (endocarditis), and widespread desquamation (staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome)—should raise suspicion for these infections. Persistent elevated inflammatory markers such as C-reactive protein or erythrocyte sedimentation rate further increase the index of suspicion for these infections. MSSA and MRSA cause an equal proportion of infectious complications (40% each) in hospitalized children with AD.4 These infection rates are consistent with that of the general pediatric inpatient populations across the United States.24 The second most common cause of SSTI and systemic infections in AD is Streptococcus pyogenes. Str pyogenes may cause infections in patients with AD by itself or in combination with S aureus. These skin infections typically present with pustules or impetigo. The lesions may appear as punched-out erosions with scalloped borders that mimic EH.25 Although SSTI and systemic infections in AD present with overt signs that facilitate diagnosis and antibiotic treatment, the so-called infected eczema associated AD exacerbation is not as clearly defined.26 Patients with severe AD exacerbation tend to have more generalized cutaneous signs and symptoms. These include erythema, swelling, oozing, and tenderness, all of which may also be signs of skin infections. However, Cochrane analysis indicates that antibiotics do not improve the severity of AD in these patients.27 The main concern with the overuse of antibiotics in AD exacerbation is the potential development of bacterial resistance and dysbiosis.28 However, apart from the outcome of AD severity, there may be a subset of patients with severe AD exacerbation who may benefit from antibiotics in terms of infections or the prevention of infectious complications.4 , 28 , 29 It has been proposed that these patients may be differentiated by a higher density of S aureus and the amount of tissue damage caused by S aureus–host interaction.29 Children with severe AD exacerbation were found to have elevated C-reactive protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rate, although these levels were significantly less than that of patients with infectious complications.4 There may be a potential use in these inflammatory markers in identifying patients with AD who are at risk for severe infectious complications.

Figure 2.

Impetigo in a child with atopic dermatitis.

Viral Infections

EH is caused by infection with herpes simplex virus (HSV)–1, which is a potentially life-threatening infectious complication in patients with AD. Nearly a third of children who are hospitalized for AD infectious complications were related to EH.4 Younger age and non-White race (African Americans, Asians, and Native Americans) are at increased risk for hospitalization with EH.30 EH can manifest with skin pruritus or pain and presence of vesicles, punched-out erosions (Fig 3 ), or hemorrhagic crusts that can become more extensive. A local skin infection may progress to disseminated vesicles with skin breakdown. Systemic EH infection may present with fever, malaise, viremia, and complications including keratoconjunctivitis, encephalitis, and septic shock.

Figure 3.

Eczema herpeticum.

Exposure to HSV-1 is common in the general population and is present in 60% of adults and 20% of children.31 Immunologic and genetic elements likely contribute to the vulnerability of a subset of patients with AD, given that EH only affects 3% of patients with AD.31 Patients with AD and EH have been reported to have interferon-γ receptor 1 single nucleotide polymorphisms and reduced interferon-γ production that may contribute to an impaired immune response to HSV-1.2 Patients with AD who develop EH tend to have more severe AD, earlier-onset AD, high total serum immunoglobulin E/peripheral eosinophils, and presence of other atopic diseases such as food allergies and asthma, as compared to their AD counterparts without EH.2 Patients with AD who have a history of S aureus skin infections are also at higher risk for developing EH.2 This is consistent with the clinical observation that EH frequently occurs concurrently with secondary S aureus skin infection in patients with AD.2

Eczema coxsackium (EC) should be considered as a differential diagnosis for EH because it can present with extensive vesicles and skin erosion.2 EC is a viral infection caused by coxsackie viruses in the enterovirus family. Some patients with EC may also have symptoms of the hand-foot-mouth disease, such as oral sores and papules involving hands and feet (Fig 4 ). Other possible symptoms include fever, sore throat, and poor appetite. In contrast to EH, EC is not life-threatening and can be managed with standard AD treatments.2 If the diagnosis between EH and EC is unclear, a lesional polymerase chain reaction for enterovirus can be obtained to differentiate between the 2 etiologies. Though more common in children, EC has also been described in adults.32

Figure 4.

Eczema coxsakium with palm lesions.

Molluscum contagiosum (MC) is a poxvirus that belongs to the Molluscipoxvirus subfamily, but it is distinct from vaccinia, variola, and cowpox viruses in the Orthopoxvirinae genus.33 MC infection in patients with AD may be diffused or along the AD distribution (Fig 5 ). Skin barrier defects predispose patients with AD to MC, and long-term scratching leads to the spread by autoinoculation. MC infection in AD has been associated with FLG LoF.34

Figure 5.

Molluscum contagiosum along with the flexural areas of a patient with atopic dermatitis.

Eczema vaccinatum (EV) is a life-threatening infection in patients with AD that is caused by a live vaccinia virus in smallpox vaccines.2 EV is reported to be rare since the discontinuation of routine smallpox vaccination in 1971. In 2002, owing to the concern that smallpox virus may be used as a weapon for bioterrorism, a national program began to vaccinate US military members, select laboratory researchers, and first responders with the smallpox vaccine.2 Pre-outbreak smallpox vaccine is contraindicated in persons with a history of AD or persons who are in close contact with patients with AD. With careful screening, there have only been a few cases of disseminated EV or EV by autoinoculation since 2002.35 Most of the affected patients have been either military members or close contacts of military members who had a recent history of smallpox vaccination. Although rare, an acute presentation of vesiculopustular/nodular rash in a patient with AD with a military background, or who had close contact with military personnel, along with a recent history of smallpox vaccination, should raise an index of suspicion for EV.

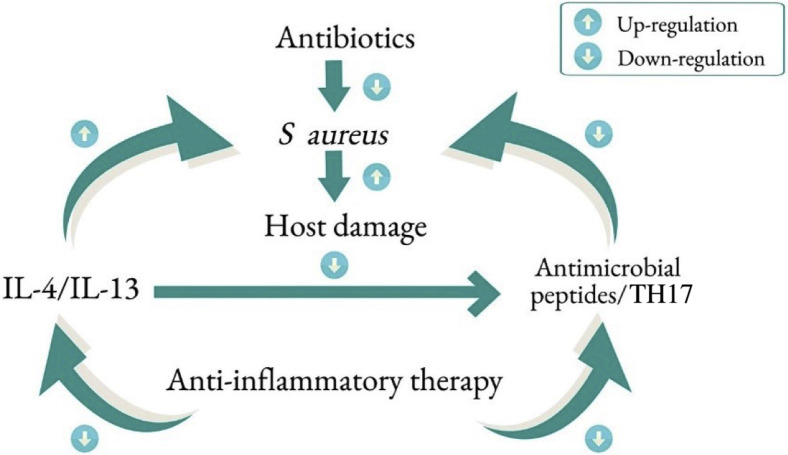

Prevention of Infections in AD

The approach in preventing infections in AD is based on addressing the predisposing factors for infections. Daily skin hydration and moisturization are recommended for patients with AD to maintain skin barrier function.36 Patients with AD should take a daily warm shower or bath, followed by gentle drying and application of a moisturizer or a prescribed topical medication. The choice of moisturizer should be based on the patient’s or parent’s preference and experience. In general, a thick or ointment-based moisturizer (eg, petrolatum) is better than cream in retaining moisture in the skin. Application of petrolatum has been indicated to up-regulate antimicrobial peptides and induce key barrier differentiation markers such as filaggrin and involucrin, in patients with AD.37 The use of standard topical anti-inflammatory medications, including topical corticosteroids (TCS) and topical calcineurin inhibitors (TCI), have been reported to improve skin barrier functions based on transepidermal water loss.38, 39, 40 Furthermore, TCS and TCI have been reported to decrease S aureus colonization in AD lesions.41, 42, 43, 44 Topical anti-inflammatory treatments have been associated with increased microbial diversity in AD lesions.45 , 46 Although multiple case reports have found an association between EH and the use of anti-inflammatory medications in AD, this was not supported by a recent multicenter study, which reviewed more than 200 cases of EH.47 The authors found that the use of TCS, TCI, systemic corticosteroid, or cyclosporine was not associated with the onset of EH. Uncontrolled AD inflammation is likely the primary risk factor for EH (or bacterial infections), rather than the anti-inflammatory treatment. Therefore, in the absence of an active infection, anti-inflammatory treatment should confer protection against infections in patients with AD (Fig 6 ). Dupilumab, a monoclonal antibody that targets the IL-4 α receptor to neutralize the effects of IL-4 and IL-13, was found to decrease S aureus colonization and increase microbial diversity.48 Pooled analysis of dupilumab clinical trials revealed significant improvement in SSTI and EH as compared with placebo.49 , 50 These observations are consistent with the suppressive effects of IL-4 and IL-13 on skin barrier functions and endogenous antimicrobial peptide expression in AD lesions, predisposing patients with AD to increased infections. Because of the current unprecedented global pandemic caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), there has been some concern about whether systemic anti-inflammatory medications for AD including dupilumab may increase the risk of patients with AD for this viral infection. Case series, mainly from Italy, thus far, have not supported an increased risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection in patients with AD who are treated with dupilumab. A global web-based registry has been set up for clinicians to monitor the risks and outcomes of SARS-CoV-2 in patients with AD receiving systemic agents, including dupilumab (www.covidderm.org).

Figure 6.

Principles of infection prevention and treatment in atopic dermatitis. IL, interleukin; S aureus, Staphylococcus aureus; TH17, T-helper 17 cells.

Attempts to decolonize S aureus is largely experimental. There is insufficient evidence that diluted bleach bath and antibiotics result in sustained decolonization of S aureus in AD.27 Dilute bleach at 0.005% was not suppressive of S aureus growth or toxin production.51 Acetic acid (apple cider vinegar) has been used as an antimicrobial bathing additive for AD,52, although its efficacy in S aureus clearance in AD has not been established. Another study reported that 0.5% acetic acid daily bath for 14 days did not improve skin barrier function or acidity in patients with AD, as compared with plain water baths.53 In contrast, skin irritation was reported in some patients treated with dilute acetic acid. Chlorhexidine bath has been used in the decolonization of MRSA in the general population, but it has not been studied adequately in AD. A potential adverse effect of this antimicrobial agent is allergic contact dermatitis.54 The Infectious Diseases Society of America published guidelines for the management of recurrent SSTI because of MRSA in 2011.55 Similar principles apply to the management of recurrent SSTI in AD. Based on these guidelines and findings of more recent studies/expert opinion, a suggested approach to the decolonization of S aureus in patients with AD with recurrent SSTIs is outlined in Table 1 .55, 56, 57

Table 1.

Suggested Decolonization Regimen to Eradicate S aureus Carriage Among Patients With AD and Their Household Contacts

| Decolonization strategy |

|---|

| 1. Optimize underlying condition |

Daily skin care

|

| Basic wound care measures for severe eczema lesions (eg, covering open or weeping wounds to prevent the spread and secondary infection). Avoidance of triggers for eczema flares. |

| 2. Education on best personal hygiene practices |

| Mechanisms of S aureus transmission (eg, skin-to-skin contact, fomites). Emphasize personal hygiene practices

|

| 3. Environmental hygiene measures |

| Regularly clean high-touch surfaces (eg, counters, door knobs, and appliances) with commercially available disinfectants. Use a barrier between exposed skin and high-touch surfaces touched by multiple people (eg, exercise equipment). Wash clothing, towels, and washcloths with hot water and detergent before reuse. Wash bedding at onset and completion of decolonization regimen. Wash hands before and after touching pets. |

| 4. Personal and household decolonization |

| Nasal decolonization with intranasal mupirocin 2% ointment twice daily for 5-10 days. And Topical decolonization with either one of the following:

|

| 5. If recurrent infections despite decolonization |

| Optimize underlying condition, personal, and environmental hygiene. Assess level of adherence with above regimen. Repeat decolonization of patient and all household contacts as follows:

|

| May consider concomitant use of oral antibiotic therapy on a case-by-case basis with rifampin and another oral agent to which the isolate is susceptible to for 5-10 days. |

Abbreviations: AD, atopic dermatitis; S aureus, Staphylococcus aureus; tsp, teaspoon.

Dilute bleach baths may be preferable to chlorhexidine solutions in patients with AD because chlorhexidine can cause skin irritation. Repeat exposure can lead to resistance and it is costlier.

Chlorhexidine can be applied as a wash or disposable wipe. Care should be taken to avoid contact with the face and the 4% solution should be thoroughly rinsed off with water after application.

Can consider changing decolonizing agents.

Management of Infectious Complications in AD

Approximately 20% of children with AD hospitalized for infectious complications had invasive bacterial infections.4 For patients with AD who have signs and symptoms of systemic illness, hospitalization and empirical intravenous antibiotics are recommended. The empirical antibiotic regimen should provide coverage against S aureus because this is the most frequently identified bacterial pathogen in AD. For critically ill patients, coverage for both MRSA and MSSA with vancomycin and an antistaphylococcal beta-lactam is appropriate because vancomycin is inferior to nafcillin or first-generation cephalosporins for the treatment of serious MSSA infections.55 For severe but non–life-threatening infections, vancomycin may be used alone as empirical therapy, pending culture results. Clindamycin can also be considered if there is no concern for an endovascular infection and the local prevalence of clindamycin resistance is less than 15%.58 Bacteremia because of S aureus requires the use of a bactericidal intravenous agent initially. For MRSA, vancomycin is the drug of choice. For MSSA, cefazolin and nafcillin are both acceptable first-line agents, though nafcillin can cause venous irritation and phlebitis when administered peripherally. As long as there are no concerns for ongoing bacteremia or an endovascular focus, completion of therapy with an oral agent to which the isolate is susceptible is appropriate in children with S aureus bacteremia.55 Duration of therapy should be determined by the clinical response, but typically 7 to 14 days is recommended. Infective endocarditis is a rare complication of AD.4 Careful auscultation for a heart murmur is recommended.

For patients with AD with uncomplicated, nonpurulent skin infection, a beta-lactam antibiotic that covers both S aureus and β-hemolytic streptococci (eg, cefazolin or cephalexin) may be sufficient pending clinical response or culture, taking into account local epidemiology and resistance patterns.4 , 55 In contrast, for patients with AD with a skin abscess, history of MRSA colonization, close contacts with a history of skin infections, or recent hospitalization, coverage for MRSA should be considered. Clindamycin, doxycycline, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, and linezolid are all acceptable oral options for MRSA skin infections in both children and adults, assuming the isolate is susceptible in-vitro.55 Of note, the rates of clindamycin resistance have been rising among both MRSA and MSSA nationally, though there is regional variation.59 Patients with AD with minor, localized skin infections such as impetigo may be treated with topical mupirocin ointment. The duration of therapy typically ranges from 5 to 10 days depending on clinical response.55

Lesional HSV polymerase chain reaction should be sent on suspicion of EH. However, treatment with systemic antiviral should not be withheld pending the results of HSV testing. Coinfection of EH with S aureus is also common and concurrent treatment with an anti–S aureus antibiotic should be considered. Table 2 provides the antiviral treatment options for EH and suggested dosing in adults and children. There are no formal guidelines regarding the preferred route of administration of antivirals or indications for hospitalization in patients with EH. For patients with extensive skin involvement, signs of systemic illness, and those less than 1 year of age, parenteral acyclovir should be considered initially. Fever and mild systemic symptoms often accompany mucocutaneous HSV infections, particularly with the initial episode. Once clinical improvement is reported, a transition to an oral agent to complete the course of therapy is appropriate. For mild cases, oral acyclovir can be considered and was associated with faster healing and resolution of pain in a randomized, placebo-controlled trial of 60 adults and adolescents with EH.60 Valacyclovir, the L-valyl ester prodrug of acyclovir, has a 3 to 5-fold greater bioavailability than oral acyclovir, which can be dosed less frequently, and with plasma concentrations are comparable with parenteral acyclovir.58 Topical antivirals do not have an appreciable benefit in HSV mucocutaneous disease and do not have a role in the treatment of EH.58 Patients with herpetic lesions on or around the eye should be emergently evaluated by an ophthalmologist.33 Rarely, EH can be complicated by HSV meningoencephalitis, which should be treated with a prolonged course of intravenous acyclovir and managed in conjunction with a neurologist and infectious disease specialist.

Table 2.

Antiviral Drugs for the Treatment of Eczema Herpeticum Owing to HSV

| Drug | Suggested adult/adolescent dose | Suggested pediatric dose | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acute treatment | |||

| Acyclovir | IV: 5-10 mg/kg/dose every 8 h Oral: 200-400 mg/dose 5 times daily |

IV: 5-10 mg/kg/dose every 8 h ≥2 y: Oral 20 mg/kg/dose 4 times daily (max 800 mg/dose) |

|

| Valacyclovir | Oral (typical): 1 g twice daily Oral (alternative): 500 mg 3 times daily |

≥3 mo: Oral: 20 mg/kg/dose twice daily (max 1000 mg/dose) |

|

| Famciclovir | Oral: 500 mg/dose twice daily | Insufficient data to recommend dosing |

|

| Foscarnet | IV: 80-120 mg/kg/day in divided doses every 8-12 h | IV (limited data): 120 mg/kg/day in divided doses every 8-12 h |

|

| Long-term suppressive therapy | |||

| Acyclovir | ≥12 y: Oral: 400 mg/dose twice daily | Oral: 20 mg/kg/dose twice daily (max 400 mg/dose) |

|

| Valacyclovir | Oral: 1 g once daily | Insufficient data to recommend dosing |

|

Abbreviations: CBC, complete blood cell count; HSV, herpes simplex virus; IV, intravenous.

Patients with AD with recurrent EH may benefit from long-term suppressive therapy, though this has not been studied. Suggested oral suppressive dosages are listed in Table 2. The need for ongoing therapy should be reassessed after 6 to 12 months. The development of resistance to acyclovir is rare in EH, but may be suspected in cases of recalcitrant EH or frequent recurrences of EH despite suppressive therapy and good adherence to long-term therapy.33 , 61 Forscarnet is the recommended therapy for acyclovir-resistant HSV infections, because acyclovir-resistant HSV isolates are also resistant to valacyclovir.

The treatment for EC is supportive of the continuation of routine skin care and AD treatments, including TCS. MC is benign, and observation is recommended in most cases. An attempt should be made to minimize scratching that spreads the lesions. This includes daily skincare and topical anti-inflammatory treatments. Sedating fast-acting antihistamines may be helpful in decreasing scratch during sleep. Treatments such as curettage, cryotherapy, salicylic acid, imiquimod, and cantharidin (beetle juice) are associated with either pain, the risk for scarring, or mixed results of efficacy.62 However, a more recent randomized placebo-controlled trial has indicated efficacy in the use of cantharidin for the treatment of pediatric MC.63 When evaluating pustule-vesicular rash in patients with AD with a military background or a history of close contact with a military personnel who had a recent vaccination, an index of suspicion for EV should be raised. Suspected cases should be reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Emergency Operation Center for assistance in diagnosis and management. EV patients with systemic symptoms may require treatment with vaccinia immune globulin.

Potential Therapy in the Pipeline

A number of agents currently in the pipeline that may help in the prevention of infections in AD include anti-inflammatory treatments that target type 2 inflammation.64 These include monoclonal antibodies that target IL-13, IL-33, thymic stromal lymphopoietin, and OX40. Janus kinase inhibition has also been shown to reduce inflammation and improve skin barrier in AD. Both topical and oral janus kinase inhibitors are in various phases of clinical trials. Topical delgocitinib has been approved for AD in Japan.65 Pruritus and associated scratching in AD can contribute to significant damage to the skin barrier and new therapeutic options are needed. A long-term trial with nemolizumab (anti–IL-31 receptor A monoclonal antibody) reported improvement in pruritus and AD severity.64 Other anti-itch treatments under investigation include transient receptor potential melastatin agonists and vanilloid antagonists.66 Improvement of skin barrier function and cutaneous innate immunity in AD is of interest, because it may prevent external triggers and skin infections.67 Although the attempt to prevent AD in healthy infants with a daily emollient application has been disappointing,68 whether or not skin barrier functions may be modified in established AD remains to be investigated. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor agonists, which increase filaggrin expression, were found to improve AD and endogenous antimicrobial production in preliminary studies.69 , 70 Directly targeting S aureus is also an active area of investigation. These treatments include natural products with anti–S aureus activity,71 synthetic antimicrobial peptides,72 and S aureus lytic agents.73 There is currently no approved S aureus vaccine. However, approaches that target S aureus toxins are in development.74 There is increasing evidence that topically applied probiotics may be a viable approach against S aureus in AD. In a small study, a gram-negative bacteria, Roseomonas mucosa, was found to improve AD and decrease S aureus burden in adults and children with AD.75 S hominis strains were found to produce an autoinducing peptide that is capable of inhibiting S aureus accessory gene regulatory quorum sensing system and prevent biofilm formation by S aureus.76

Conclusion

AD is a complex disease associated with skin barrier defects that result in allergen or pathogen invasion and dysfunctional immune responses, causing a vicious cycle of inflammation. The skin microbiome is altered because of this dysregulation and pathogenic organisms such as S aureus are more likely to colonize the skin. The combination of skin barrier defects, immune dysregulation, and alteration in the skin microbiome result in an increased risk for skin infections.

The prevention of infection in AD should emphasize skin barrier repair and maintenance anti-inflammatory medications without relying on antibiotics. The need for antibiotics in patients with severe AD exacerbations remains controversial. This is because some of the signs and symptoms associated with severe AD exacerbation resemble that of bacterial skin infections. It is possible that there is a threshold at which S aureus levels and the extent of host tissue damage evolve into an infection. Studies are needed to investigate the biomarkers that assist in determining this threshold. Acute-phase response markers such as C-reactive protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rate may be helpful in determining the need for antibiotics in patients with severe AD exacerbation who are suspected of having infections. Future studies should also address whether anti-inflammatory treatments, especially those that specifically target type 2 inflammation, may benefit patients with AD with active infection. This is based on the premise that suppressing type 2 inflammation may lead to the improvement of immunity against microbial pathogens.

Footnotes

Disclosures: The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Funding: The authors have no funding sources to report.

References

- 1.Capozza K., Gadd H., Kelley K., Russell S., Shi V., Schwartz A. Insights from caregivers on the impact of pediatric atopic dermatitis on families: “I’m tired, overwhelmed, and feel like I’m failing as a mother.”. Dermatitis. 2020;31(3):223–227. doi: 10.1097/DER.0000000000000582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ong P.Y., Leung D.Y. Bacterial and viral infections in atopic dermatitis: a comprehensive review. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2016;51(3):329–337. doi: 10.1007/s12016-016-8548-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Narla S., Silverberg J.I. Association between atopic dermatitis and serious cutaneous, multiorgan, and systemic infections in US adults. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2018;120(1):66–72.e11. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2017.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang V., Keefer M., Ong P.Y. Antibiotic choice and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus rate in children hospitalized for atopic dermatitis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2019;122(3):314–317. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2018.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sandhu J.K., Salame N., Ehsani-Chimeh N., Armstrong A.W. Economic burden of cutaneous infections in children and adults with atopic dermatitis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2019;36(3):303–310. doi: 10.1111/pde.13828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grice K., Sattar H., Baker H., Sharratt M. The relationship of transepidermal water loss to skin temperature in psoriasis and eczema. J Invest Dermatol. 1975;64(5):313–315. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12512258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Elias P.M., Sugarman J. Does moisturizing the skin equate with barrier repair therapy? Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2018;121(6) doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2018.07.008. 653–656.e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rippke F., Schreiner V., Doering T., Maibach H.I. Stratum corneum pH in atopic dermatitis: impact on skin barrier function and colonization with Staphylococcus aureus. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2004;5(4):217–223. doi: 10.2165/00128071-200405040-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smieszek S.P., Welsh S., Xiao C., et al. Correlation of age-of-onset of atopic dermatitis with filaggrin loss-of-function variant status. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):2721. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-59627-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Margolis D.J., Mitra N., Wubbenhorst B., et al. Association of filaggrin loss-of-function variants with race in children with atopic dermatitis. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155(11):1269–1276. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.1946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berdyshev E., Goleva E., Bronova I., et al. Lipid abnormalities in atopic skin are driven by type 2 cytokines. JCI Insight. 2018;3(4) doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.98006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stier M.T., Peebles R.S., Jr. Innate lymphoid cells and allergic disease. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2017;119(6):480–488. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2017.08.290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ong P.Y., Ohtake T., Brandt C., et al. Endogenous antimicrobial peptides and skin infections in atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(15):1151–1160. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ryffel B., Alves-Filho J.C. ILC2s and basophils team up to orchestrate IL-33-induced atopic dermatitis. J Invest Dermatol. 2019;139(10):2077–2079. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2019.06.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leyva-Castillo J.M., Galand C., Mashiko S., et al. ILC2 activation by keratinocyte-derived IL-25 drives IL-13 production at sites of allergic skin inflammation. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;145(6):1606–1614.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.02.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Iwamoto K., Nümm T.J., Koch S., Herrmann N., Leib N., Bieber T. Langerhans and inflammatory dendritic epidermal cells in atopic dermatitis are tolerized toward TLR2 activation. Allergy. 2018;73(11):2205–2213. doi: 10.1111/all.13460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mack M.R., Brestoff J.R., Berrien-Elliott M.M., et al. Blood natural killer cell deficiency reveals an immunotherapy strategy for atopic dermatitis. Sci Transl Med. 2020;12(532) doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aay1005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fyhrquist N., Muirhead G., Prast-Nielsen S., et al. Microbe-host interplay in atopic dermatitis and psoriasis. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):4703. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-12253-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim J., Kim B.E., Ahn K., Leung D.Y.M. Interactions between atopic dermatitis and Staphylococcus aureus infection: clinical implications. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2019;11(5):593–603. doi: 10.4168/aair.2019.11.5.593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Orfali R.L., Yoshikawa F.S.Y., Oliveira L.M.D.S., et al. Staphylococcal enterotoxins modulate the effector CD4+ T cell response by reshaping the gene expression profile in adults with atopic dermatitis. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):13082. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-49421-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Orfali R.L., da Silva Oliveira L.M., de Lima J.F., et al. Staphylococcus aureus enterotoxins modulate IL-22-secreting cells in adults with atopic dermatitis. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):6665. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-25125-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nakatsuji T., Gallo R.L. The role of the skin microbiome in atopic dermatitis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2019;122(3):263–269. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2018.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stevens D.L., Bisno A.L., Chambers H.F., et al. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of skin and soft tissue infections: 2014 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59(2):e10–e52. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gerber J.S., Coffin S.E., Smathers S.A., Zaoutis T.E. Trends in the incidence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection in children’s hospitals in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49(1):65–71. doi: 10.1086/599348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shayegan L.H., Richards L.E., Morel K.D., Levin L.E. Punched-out erosions with scalloped borders: Group A Streptococcal pustulosis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2019;36(6):995–996. doi: 10.1111/pde.13956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Francis N.A., Ridd M.J., Thomas-Jones E., et al. Oral and topical antibiotics for clinically infected eczema in children: a pragmatic randomized controlled trial in ambulatory care. Ann Fam Med. 2017;15(2):124–130. doi: 10.1370/afm.2038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.George S.M., Karanovic S., Harrison D.A., et al. Interventions to reduce Staphylococcus aureus in the management of eczema. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;2019(10):CD003871. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003871.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harkins C.P., Holden M.T.G., Irvine A.D. Antimicrobial resistance in atopic dermatitis: need for an urgent rethink. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2019;122(3):236–240. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2018.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alexander H., Paller A.S., Traidl-Hoffmann C., et al. The role of bacterial skin infections in atopic dermatitis: expert statement and review from the International Eczema Council Skin Infection Group. Br J Dermatol. 2020;182(6):1331–1342. doi: 10.1111/bjd.18643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hsu D.Y., Shinkai K., Silverberg J.I. Epidemiology of eczema herpeticum in hospitalized U.S. Children: analysis of a nationwide cohort. J Invest Dermatol. 2018;138(2):265–272. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2017.08.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Leung D.Y. Why is eczema herpeticum unexpectedly rare? Antiviral Res. 2013;98(2):153–157. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2013.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harris P.N.A., Wang A.D., Yin M., Lee C.K., Archuleta S. Atypical hand, foot, and mouth disease: eczema coxsackium can also occur in adults. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014;14(11):1043. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(14)70976-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wollenberg A., Wetzel S., Burgdorf W.H., Haas J. Viral infections in atopic dermatitis: pathogenic aspects and clinical management. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;112(4):667–674. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2003.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Manti S., Amorini M., Cuppari C., et al. Filaggrin mutations and molluscum contagiosum skin infection in patients with atopic dermatitis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2017;119(5):446–451. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2017.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Said M.A., Haile C., Palabindala V., et al. Transmission of vaccinia virus, possibly through sexual contact, to a woman at high risk for adverse complications. Mil Med. 2013;178(12):e1375–e1378. doi: 10.7205/MILMED-D-13-00233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Boguniewicz M., Fonacier L., Guttman-Yassky E., Ong P.Y., Silverberg J., Farrar J.R. Atopic dermatitis yardstick: practical recommendations for an evolving therapeutic landscape. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2018;120(1):10–22.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2017.10.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Czarnowicki T., Malajian D., Khattri S., et al. Petrolatum: barrier repair and antimicrobial responses underlying this “inert” moisturizer. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;137(4):1091–1102.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Woods M.T., Brown P.A., Baig-Lewis S.F., Simpson E.L. Effects of a novel formulation of fluocinonide 0.1% cream on skin barrier function in atopic dermatitis. J Drugs Dermatol. 2011;10(2):171–176. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dähnhardt-Pfeiffer S., Dähnhardt D., Buchner M., Walter K., Proksch E., Fölster-Holst R. Comparison of effects of tacrolimus ointment and mometasone furoate cream on the epidermal barrier of patients with atopic dermatitis. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2013;11(5):437–443. doi: 10.1111/ddg.12074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jensen J.M., Weppner M., Dähnhardt-Pfeiffer S., et al. Effects of pimecrolimus compared with triamcinolone acetonide cream on skin barrier structure in atopic dermatitis: a randomized, double-blind, right-left arm trial. Acta Derm Venereol. 2013;93(5):515–519. doi: 10.2340/00015555-1533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nilsson E.J., Henning C.G., Magnusson J. Topical corticosteroids and Staphylococcus aureus in atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;27(1):29–34. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(92)70151-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pournaras C.C., Lübbe J., Saurat J.H. Staphylococcal colonization in atopic dermatitis treatment with topical tacrolimus (Fk506) J Invest Dermatol. 2001;116(3):480–481. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2001.12799.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hung S.H., Lin Y.T., Chu C.Y., et al. Staphylococcus colonization in atopic dermatitis treated with fluticasone or tacrolimus with or without antibiotics. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2007;98(1):51–56. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)60859-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gong J.Q., Lin L., Lin T., et al. Skin colonization by Staphylococcus aureus in patients with eczema and atopic dermatitis and relevant combined topical therapy: a double-blind multicentre randomized controlled trial. Br J Dermatol. 2006;155(4):680–687. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2006.07410.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kong H.H., Oh J., Deming C., et al. Temporal shifts in the skin microbiome associated with disease flares and treatment in children with atopic dermatitis. Genome Res. 2012;22(5):850–859. doi: 10.1101/gr.131029.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gonzalez M.E., Schaffer J.V., Orlow S.J., et al. Cutaneous microbiome effects of fluticasone propionate cream and adjunctive bleach baths in childhood atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75(3) doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2016.04.066. 481–493.e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Seegräber M., Worm M., Werfel T., et al. Recurrent eczema herpeticum - a retrospective European multicenter study evaluating the clinical characteristics of eczema herpeticum cases in atopic dermatitis patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34(5):1074–1079. doi: 10.1111/jdv.16090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Callewaert C., Nakatsuji T., Knight R., et al. IL-4Rα blockade by dupilumab decreases Staphylococcus aureus colonization and increases microbial diversity in atopic dermatitis. J Invest Dermatol. 2020;140(1) doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2019.05.024. 191–202.e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Eichenfield L.F., Bieber T., Beck L.A., et al. Infections in dupilumab clinical trials in atopic dermatitis: a comprehensive pooled analysis. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2019;20(3):443–456. doi: 10.1007/s40257-019-00445-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fleming P., Drucker A.M. Risk of infection in patients with atopic dermatitis treated with dupilumab: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78(1) doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2017.09.052. 62–69.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sawada Y., Tong Y., Barangi M., et al. Dilute bleach baths used for treatment of atopic dermatitis are not antimicrobial in vitro. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019;143(5):1946–1948. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2019.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Asch S., Vork D.L., Joseph J., Major-Elechi B., Tollefson M.M. Comparison of bleach, acetic acid, and other topical anti-infective treatments in pediatric atopic dermatitis: a retrospective cohort study on antibiotic exposure. Pediatr Dermatol. 2019;36(1):115–120. doi: 10.1111/pde.13663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Luu L.A., Flowers R.H., Kellams A.L., et al. Apple cider vinegar soaks [0.5%] as a treatment for atopic dermatitis do not improve skin barrier integrity. Pediatr Dermatol. 2019;36(5):634–639. doi: 10.1111/pde.13888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Magdaleno-Tapial J., Martínez-Doménech A., Valenzuela-Oñate C., Ferrer-Guillén B., Esteve-Martínez A., Zaragoza-Ninet V. Allergic contact dermatitis to chlorhexidine in pediatric patients. Pediatr Dermatol. 2019;36(4):540–541. doi: 10.1111/pde.13808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Liu C., Bayer A., Cosgrove S.E., et al. Clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Disease Society of America for the treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in adults and children: executive summary. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52(3):285–292. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hogan P.G., Mork R.L., Thompson R.M., et al. Environmental methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus contamination, persistent colonization, and subsequent skin and soft tissue infection. JAMA Pediatr. 2020;174(6):1–11. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.0132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.McNeil J.C., Fritz S.A. Prevention strategies for recurrent community-associated Staphylococcus aureus skin and soft tissue infections. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2019;21(4):12. doi: 10.1007/s11908-019-0670-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kimberlin D., Brady M., Jackson M., Long S., editors. Red Book: 2018 Report of the Committee of Infectious Diseases. American Academy of Pediatrics; Itasca, IL: 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sutter D.E., Milburn E., Chukwuma U., Dzialowy N., Maranich A.M., Hospenthal D.R. Changing susceptibility of Staphylococcus aureus in a US pediatric population. Pediatrics. 2016;137(4) doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-3099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Niimura M., Nishikawa T. Treatment of eczema herpeticum with oral acyclovir. Am J Med. 1988;85(2A):49–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Frisch S., Siegfried E.C. The clinical spectrum and therapeutic challenge of eczema herpeticum. Pediatr Dermatol. 2011;28(1):46–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2010.01356.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Moye V., Cathcart S., Burkhart C.N., Morrell D.S. Beetle juice: a guide for the use of cantharidin in the treatment of molluscum contagiosum. Dermatol Ther. 2013;26(6):445–451. doi: 10.1111/dth.12105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Guzman A.K., Schairer D.O., Garelik J.L., Cohen S.R. Safety and efficacy of topical cantharidin for the treatment of pediatric molluscum contagiosum: a prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot trial. Int J Dermatol. 2018;57(8):1001–1006. doi: 10.1111/ijd.14079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Renert-Yuval Y., Guttman-Yassky E. New treatments for atopic dermatitis targeting beyond IL-4/IL-13 cytokines. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2020;124(1):28–35. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2019.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dhillon S. Delgocitinib: first approval. Drugs. 2020;80(6):609–615. doi: 10.1007/s40265-020-01291-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lee Y.W., Won C.H., Jung K., et al. Efficacy and safety of PAC-14028 cream - a novel, topical, nonsteroidal, selective TRPV1 antagonist in patients with mild-to-moderate atopic dermatitis: a phase IIb randomized trial. Br J Dermatol. 2019;180(5):1030–1038. doi: 10.1111/bjd.17455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sugita K., Soyka M.B., Wawrzyniak P., et al. Outside-in hypothesis revisited: the role of microbial, epithelial, and immune interactions. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2020;125:517–527. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2020.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Perrett K.P., Peters R.L. Emollients for prevention of atopic dermatitis in infancy. Lancet. 2020;395(10228):923–924. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)33174-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Peppers J., Paller A.S., Maeda-Chubachi T., et al. A phase 2, randomized dose-finding study of tapinarof (GSK2894512 cream) for the treatment of atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80(1):89–98.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.06.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Smits J.P.H., Ederveen T.H.A., Rikken G., et al. Targeting the cutaneous microbiota in atopic dermatitis by coal tar via AHR-dependent induction of antimicrobial peptides. J Invest Dermatol. 2020;140(2):415–424.e10. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2019.06.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Nakagawa S., Hillebrand G.G., Nunez G. Rosmarinus officinalis L. (Rosemary) extracts containing carnosic acid and carnosol are potent quorum sensing inhibitors of Staphylococcus aureus virulence. Antibiotics (Basel) 2020;9(4):149. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics9040149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Niemeyer-van der Kolk T., van der Wall H., Hogendoorn G.K., et al. Pharmacodynamic effects of topical omiganan in patients with mild to moderate atopic dermatitis in a randomized, placebo-controlled, phase II trial [e-pub ahead of print]. Clin Transl Sci. https://doi.org/10.1111/cts.12792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 73.Fowler V.G., Jr., Das A.F., Lipka-Diamond J., et al. Exebacase for patients with Staphylococcus aureus bloodstream infection and endocarditis. J Clin Invest. 2020;130(7):3750–3760. doi: 10.1172/JCI136577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Miller L.S., Fowler V.G., Shukla S.K., Rose W.E., Proctor R.A. Development of a vaccine against Staphylococcus aureus invasive infections: evidence based on human immunity, genetics, and bacterial evasion mechanisms. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2020;44(1):123–153. doi: 10.1093/femsre/fuz030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Myles I.A., Earland N.J., Anderson E.D., et al. First-in-human topical microbiome transplantation with Roseomonas mucosa for atopic dermatitis. JCI Insight. 2018;3(9) doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.120608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Williams M.R., Costa S.K., Zaramela L.S., et al. Quorum sensing between bacterial species on the skin protects against epidermal injury in atopic dermatitis. Sci Transl Med. 2019;11(490) doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aat8329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]