Abstract

Objective

Explore changes in micro-RNA (miRNA) expression in blood after sport-related concussion (SRC) in collegiate athletes.

Methods

Twenty-seven collegiate athletes (~41% male, ~75% white, age 18.8 ± 0.8 years) provided both baseline and post-SRC blood samples. Serum was analyzed for expression of miR-153–3p (n = 27), miR-223–3p (n = 23), miR-26a-5p (n = 26), miR-423–3p (n = 23), and miR-let-7a-5p (n = 23) at both time points via quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR). Nonparametric analyses were used to compare miRNA expression changes between baseline and SRC and to evaluate associations with clinical outcomes (symptom severity, cognition, balance, and oculomotor function, and clinical recovery time).

Results

Participants manifested a significant increase in miRNA expression following SRC for miR153–3p (Z = −2.180, p = .029, 59% of the participants increased post-SRC), miR223–3p (Z = −1.998, p = .046, 70% increased), and miR-let-7a-5p (Z = −2.190, p = .029, 65% increased). There were no statistically significant associations between changes in miRNA expression and clinical test scores, acute symptom severity, or clinical recovery time.

Conclusion

MiR-153–3p, miR-223–3p, and miR-let-7a-5p were significantly upregulated acutely following SRC in male and female collegiate athletes compared to baseline levels, though several athletes demonstrated no change or a decrease in expression. The biological mechanisms and functional implications of the increased expression of these circulating miRNA are unclear and require more research, as does their relevance to clinical outcomes.

Keywords: Concussion, biomarker, micro-RNA, miR-153, miR-223, miR-let-7a

Introduction

Developing objective indicators of sport-related concussion (SRC) remains an essential goal for improving diagnostic accuracy and informing clinical decision-making. Growing knowledge that individual aspects of the neurophysiological response to SRC occur and recover at different times relative to clinical characteristics (1,2) has sparked research investigating the potential role of advanced biomarkers. Several candidate fluid biomarkers utilized at first in the study of moderate to severe traumatic brain injury (TBI) have emerged in research on mild TBI and SRC.

Some of the most commonly studied blood biomarkers measured in serum or plasma are S100 calcium-binding protein B (S100B), ubiquitin carboxy-terminal hydrolase L1 (UCH-L1), glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), and tau. We investigated the diagnostic accuracy of these and other serum biomarkers previously (see Concussion BASICS: Part 3), and also reported data regarding their normative distributions and reliability (Concussion BASICS: Part 1). A reliable and valid blood biomarker has not yet been identified and continued research into these and other potential biomarkers is warranted (3,4). Micro-RNA represents one potential novel research avenue in mTBI and SRC (5).

Micro-RNAs (miRNA) are small, non-protein-coding, RNA sequences that are highly conserved across species and are implicated in post-transcription protein regulation. Conservation across animal species underscores a unique role for miRNA in translational research. An estimated two-thirds of all protein-coding genes within the human genome are thought to bind with miRNA, highlighting their importance in the regulation of protein synthesis (6).Micro-RNA play a critical role in modulating immune functioning, cellular metabolism, and apoptosis (5). Accordingly, they have been explored as potential biomarkers for a variety of conditions including cancer (7), autoimmune disorders (8), and neurodegenerative disease (9).

Micro-RNAs may also be objective markers for SRC given that they easily cross the blood-brain barrier and are implicated in cellular aspects of nervous system injury (e.g. neuroinflammation and repair) and degeneration (5). The goal of this exploratory study was to compare miRNA expression following SRC to baseline (pre-injury) expression. We specifically evaluated a panel of miRNAs that previous studies indicated were differentially expressed in association with central nervous system (CNS) dysfunction (Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of findings of circulating miRNA associated with central nervous system dysfunction.

| miRNA | Animal Models | Human/Human Cell Lines |

|---|---|---|

| miR-153-3p | • Upregulation in hippocampus following controlled cortical impact (rat) (10,11) • Negatively regulates amyloid precursor protein expression (mouse) (10) |

• Downregulated in Alzheimer’s disease versus controls (12) • Negatively regulates amyloid precursor protein expression in cultured human fetal brain cells (12) |

| miR-223-3p | • Upregulation in hippocampus following controlled cortical impact (rat) (13) • Upregulation in spinal cord tissue following spinal cord injury (rat) (14) |

• Upregulation in ischemic stroke versus controls (15) • Downregulation in Alzheimer’s disease versus controls (16) |

| miR-26a-5p | • Upregulation in embryonic astrocytes relative to embryonic neurons (mouse) (17) | • Upregulation in blood serum of patients with chronic traumatic brain injury induced hypopituitarism (18) |

| miR-423-3p | • Upregulation in hippocampus of chronic temporal lobe epilepsy (rat) (19) | • Differentiated patients with greater risk of amnesia following mild traumatic brain injury (blood plasma) (20) • Upregulated in Alzheimer’s disease versus controls (hippocampus and medial frontal gyrus) (21) • Downregulated in acute stroke (22) |

| miR-let-7a-5p | • Upregulation following rat spinal cord injury (23) | • Downregulated in recovery following stroke (22) |

Methods

Participants

These data are a subset of a larger group of studies collectively known as the Concussion Biomarkers Assessed from Serum in Collegiate Student-Athletes (BASICS) study (currently under review).

Serum samples were obtained from male and female University of Florida varsity athletes (age mean ±SD = 18.8 ± 0.8 years). A trained phlebotomist performed all blood draws following individual athlete consent according to a protocol approved by an independent ethical and biomedical research review board (Western IRB) with approved language by the university’s institutional review board (IRB-01). Sample size varied slightly for each miRNA biomarker (N = 23–27). All participants in this study provided two blood samples via venipuncture: (1) a healthy baseline blood sample obtained during the athletes’ respective offseasons and (2) a post-SRC blood sample obtained acutely following an SRC diagnosed by a certified athletic trainer and certified sports medicine-trained team physician according to consensus guidelines (24).

Baseline blood draws were performed outside of each athlete’s respective competitive sports season in order to maximize the likelihood that the protein expression represented a true baseline value. We determined the most recent exposure to head impacts for football and women’s soccer players based on team schedules, typical date ranges for supervised athletic activity potentially posing a risk of head impacts, and, in the case of incoming freshmen football players, inspection of their respective high school football schedules indicating date of their last competition prior to enrollment in the study. Based on all available information for the broader Concussion BASICS sample, the median time between last exposure to head impacts and baseline blood draw was 80 days (mean 98.4 days). Post-SRC blood draws were obtained as soon as possible following diagnosed concussion (mean 405.8 min). Micro-RNA biomarker-specific sample characteristics are provided in Table 2. All baseline and post-SRC blood draws for the current sample were obtained between 2012 and 2015.

Table 2.

Sample characteristics stratified by miRNA biomarker.

| miR-153-3p | miR-223-3p | miR-26a-5p | miR-423-3p | miR-let-7a-5p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 27 | 23 | 26 | 23 | 23 |

| Age, y (mean [SD]) | 18.8 (0.8) | 18.9 (0.8) | 18.8 (0.8) | 18.8 (0.9) | 18.7 (0.8) |

| Sex (%Male) | 40.7 | 43.5 | 38.5 | 39.1 | 34.8 |

| Race (%White) | 74.1 | 73.9 | 73.1 | 73.9 | 78.3 |

| Concussion History (%) | |||||

| 0 | 55.6 | 52.2 | 57.7 | 56.5 | 56.5 |

| 1 | 22.2 | 26.1 | 19.2 | 21.7 | 21.7 |

| 2+ | 22.2 | 21.7 | 19.2 | 21.7 | 21.7 |

| Time Between Concussion and Blood Draw, m (mean [median]) | 384 (232) | 411 (232) | 394 (232) | 416 (233) | 424 (233) |

Note: Analyses of variance and chi-square analyses indicated no between-miRNA biomarker group differences in any above factor (p > .05 for all analyses).

Abbrev: m – minutes; SD – standard deviation; y – years

Micro-RNA analysis

Blood samples were drawn via venipuncture, collected in Serum Separator Tubes (SST®, Quest Diagnostics), left to clot for 30–60 minutes, and centrifuged at 1,500 rpm for 15 min. The resulting serum was isolated, aliquoted, and stored at −80°C and then shipped on dry ice to a central repository for storage until the time of testing as per a pre-defined specimen handling the procedure.

RNA isolation and reverse transcription

Micro-RNA were analyzed via quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR). Total RNA, including miRNA, was isolated from 100 μL of serum using the MagMAX mirVana Total RNA Isolation Kit (#A27828). The synthetic cel-miR-39–3p spike-in RNA oligo was added to the total RNA at a final concentration of 1 pM. A 2 μL of total RNA was used for reverse transcription using the TaqMan® Advanced miRNA cDNA Synthesis Kit (#A28007). The PCR reaction condition was performed with the following program: (1) 42°C, (2) 15 min, 85°C, (3) 5 min, 4°C.

MiR-amp PCR reaction

5 μL RT product was used for miR-amp PCR reaction by the TaqMan® Advanced miRNA cDNA Synthesis Kit. The PCR reaction was performed with the following program: (1) 95°C, 5 min, (2) 14 cycle*(95°C, 3 s → 60°C, 30 s), (3) 99°C, 10 min → 4°C Hold.

Quantitative PCR

0.25 μL miR-Amp reaction product was diluted with 2.25 μL nuclease-free H2O to generate 10X-dilution miR-amp reaction product. Each PCR reaction included 0.25 μL miR-Amp reaction product with TaqMan® Fast Advanced Master Mix (#4444556). A 10-μL reaction volume was used according to the following table: Each sample was tested in triplicate. ViiA™ 7 Real-Time PCR System was used with the following program: (1) 95°C, 20 s) and 40 cycles (95°C, 1 s → 60°C, 20 s).

Data analysis

The Thermo Fisher Cloud Relative Quantification (RQ) Analysis Module was used to analyze the qPCR data. Poor data were automatically filtered using the Amp Score flag (less than 0.9) and the Cq Confidence flag (less than 0.6). The amplification curves for all flagged data were manually inspected by a trained qPCR technician and only retained for further analysis if the curves were determined to reflect true amplification. The RQ analysis approach involves normalization of each sample to the exogenous spike-in control (delta-CT or dCt) followed by a comparison of each sample to a reference sample (delta-delta-Ct or ddCt). The reference sample was one that demonstrated appreciable expression in nearly all targets; the RQ value for the reference sample was 1. All other samples were calculated relative to that sample. A typical Ct cut-off for ‘real’ expression is Ct = 35 for 10 μL reactions in a 384-well plate format; however, when pre-amplification is performed, a typical cut-off is Ct = 30. Therefore, samples with average Ct>30 are considered to have little to no expression of the target miRNA. miRNA samples with mean Ct>30 were not excluded from analyses since both a baseline and post-SRC value were available for each participant, and relevant within-subject data could still be ascertained. The percentage of samples with Ct>30 are reported in the results.

Clinical outcomes

Clinical data included symptom severity (Sport Concussion Assessment Tool [SCAT3] Symptom Inventory), cognitive tests (Standardized Assessment of Concussion [SAC (25)] and Immediate Postconcussion Assessment and Cognitive Testing [ImPACT (26)] scores), postural stability (Balance Error Scoring System [BESS (27)]), and saccades/timed number naming (King-Devick test [KD (28)]), which are described in more detail elsewhere (see Concussion BASICS Part 1). Baseline test scores were obtained in the course of routine preseason pre-participation examinations as required by the university’s concussion management protocol. Post-SRC scores on the same tests, obtained closest to the post-SRC blood draw, were used for analyses. All were done within 5 days of one another with the majority occurring within 24 h. The median time between blood draw and symptom severity, SAC, BESS, and KD was 0 days (same day as blood draw) and 1 day for ImPACT (the day before or after blood draw). All ImPACT data were found to be valid based on embedded validity criteria. Both the change scores (from baseline) and the absolute post-SRC scores were evaluated. Clinical recovery was defined as the amount of time (days) between the date the participant sustained an SRC and the date of clearance for full return to athletic activity. This time frame includes the combined time of symptom resolution and completion of a graduated physical exertion protocol. Standard protocol followed the 2009 and 2013 Concussion in Sport Group consensus guidelines and progressed athletes from rest and light aerobic activity (Stages 1 and 2), to anaerobic and sport-specific activity without contact (Stages 3 and 4), to clearance for return to sport (noncontact sports) or full contact activity (contact sports; Stage 5). Date of Stage 5 clearance was used as the clinical recovery time point (24,29).

Statistical analyses

We utilized nonparametric analyses due to non-normally distributed data. Within-subject changes in RQ of a given miRNA biomarker from baseline to post-SRC were analyzed using Wilcoxon Signed Rank tests. Specifically, an increase in RQ from baseline to post-SRC indicated increased expression of the miRNA biomarker and a decrease in RQ from baseline to post-SRC indicated decreased expression of the miRNA biomarker. Effect size estimates were calculated using the common language effect size statistic proposed by Grissom and Kim (30), also known as a probability index. This is interpreted similarly to an area under the curve (AUC) statistic; it is the likelihood that, in a randomly selected matched pair (i.e. a matched baseline and post-concussion pair), the score from condition 2 (i.e. the post-concussion value) will be greater than the score from condition 1 (i.e. the baseline value). Therefore, a probability index of 0.5 means there is an equal likelihood (50% chance) that the post-concussion value will be higher or lower than the baseline value (i.e. random chance or negligible effect). A probability index of 0.75 means that there is a 75% chance that the post-concussion value will be higher than the baseline value. The following cut-offs are used in this study based on previously published relationships between AUC values and traditional conventions for Cohen’s d effect sizes (31): 0.56 (equivalent to d = 0.2) is a small effect, 0.64 (equivalent to d = 0.5) is a medium effect, and 0.71 (equivalent to d = 0.8) is a large effect.

Associations between changes in miRNA RQ and post-SRC clinical outcomes were analyzed using Spearman correlations. A priori significance was set at p < .05 for pre- to post-SRC RQ changes, and p < .01 for analyses of associations with clinical outcomes to conservatively adjust for multiple comparisons. We reported correlations with at least a moderate effect size (ρ[rho]>.300) given that our limited sample size may be inadequately powered to detect a statistically significant relationship if one exists. Clinical outcomes were also compared between participants demonstrating increased expression of a given miRNA biomarker and participants demonstrating no change or decreased expression using Mann–Whitney U tests.

Results

There were no differences in age, sex, race, concussion history, or time from SRC to obtaining a blood sample between miRNA biomarker samples (Table 2). Change in miRNA expression was not significantly associated with sex, race, or the number of previously diagnosed concussions (p > .05 for all analyses). The percentages of samples with mean Ct>30 (signifying very low expression of miRNA) for each miRNA were as follows (baseline/post-SRC): miR-153–3p (93%/81%), miR-223–3p (4%/0%), miR-26a-5p (0%/4%), miR-423–3p (9%/0%), and miR-let-7a-5p (0%/4%). Results pertaining to miR-153–3p should be interpreted cautiously given the high rate of both baseline and post-SRC samples with low expression of miRNA.

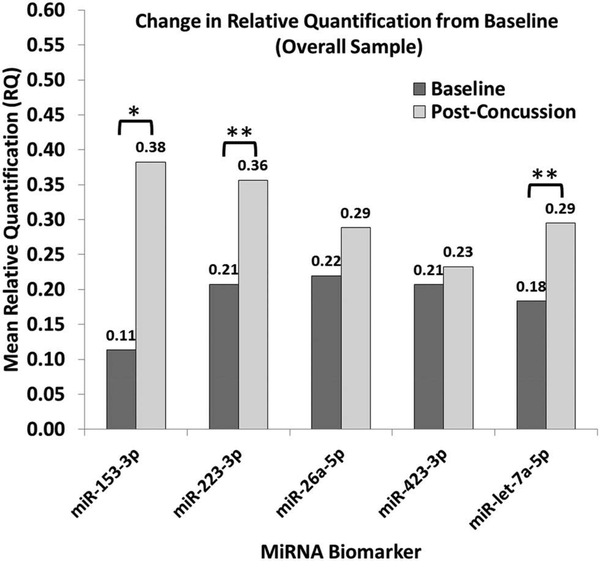

Participants exhibited a significant increase in miRNA expression following SRC for miR153–3p (Z = −2.180, p = .029), miR223–3p (Z = −1.998, p = .046), and miR-let −7a-5p (Z = −2.190, p = .029). No significant changes in miR26a-5p or miR423–3p were noted (p > .05). Figure 1 shows post-SRC miRNA expression changes from baseline and displays associated effect sizes based on the probability of an elevated RQ value. Further, the actual percentage of participants exhibiting increased, decreased, or no change in miRNA expression for each biomarker are provided in Table 3. We stratified data according to the elapsed time between SRC and obtaining the post-SRC blood sample using a median split (~4 hours). Sample size limitations restricted formal analyses, but a qualitative examination of the data suggests no apparent differences in the proportion of participants exhibiting elevated miRNA expression after SRC based on the timing of the blood draw (Table 3).

Figure 1.

Post-concussion change from baseline in mean relative quantification (RQ) of each micro-RNA biomarker.

*Medium effect size (probability index [p] = 0.64)**Large effect size (probability index [p] > 0.71)

Table 3.

Descriptive results of Wilcoxon signed-rank test assessing within-subject changes in serum miRNA expression from baseline to post-SRC (percentage of participants indicated). Results are further stratified by elapsed time between SRC and obtaining the post-SRC blood sample based on a median split (4 hours post-SRC).

| Overall |

Blood drawn <4 h after SRC |

Blood drawn >4 h after SRC |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MiRNA | C > B | C < B | C = B | C > B | C < B | C = B | C > B | C < B | C = B |

| miR153-3p | 59.3* | 33.3 | 7.4 | 64.7 | 23.5 | 11.8 | 50.0 | 50.0 | 0.0 |

| miR223-3p | 69.6* | 26.1 | 4.3 | 71.4 | 21.4 | 7.1 | 66.6 | 33.3 | 0.0 |

| miR26a-5p | 57.7 | 34.6 | 7.7 | 56.3 | 43.8 | 0.0 | 60.0 | 20.0 | 20.0 |

| miR423-3p | 52.3 | 47.7 | 0.0 | 57.1 | 42.9 | 0.0 | 44.4 | 55.5 | 0.0 |

| miR-let-7a-5p | 65.2* | 26.1 | 8.7 | 61.5 | 30.8 | 7.7 | 70.0 | 20.0 | 10.0 |

Significant increase from baseline (p < .05). Wilcoxon signed-rank statistics are not reported for analyses stratified by time between SRC and blood draw due to small sample sizes.

Abbrev: C > B – Post-concussion expression greater than baseline expression; C < B – Post-concussion expression less than baseline expression; C = B – Post-concussion expression equal to baseline expression; h – hours; SRC – sport-related concussion

Association with clinical outcomes

There were no statistically significant associations between changes in miRNA expression and either changes in clinical test scores or absolute post-SRC test scores (p > .01 for all analyses). A greater increase in miR-423–3p expression may be associated with a greater decrease in ImPACT Verbal Memory (ρ = −.336, p = .116) relative to baseline. A greater increase in miR-153–3p expression from baseline may be associated with slower ImPACT Reaction Time after SRC (ρ = .330, p = .093). Greater increases in miR-26a-5p (ρ = −.324, p = .114) and miR-423–3p expression (ρ = −.363, p = .089) from baseline may be associated with lower ImPACT Verbal Memory scores after SRC. Finally, a greater increase in miR-let-7a-5p expression from baseline may be associated with more errors on the BESS (ρ = .523, r = .026), lower ImPACT Verbal Memory (ρ = −.374, r = .086) and Visual Memory scores (ρ = −.423, p = .050), and slower ImPACT Reaction Time (ρ = .443, p = .039).

Participants exhibiting increased expression of miR-let-7a-5p had significantly slower ImPACT Reaction Time after SRC than those with no change or a decreased expression of miR-let-7a-5p (U = 13.5, Z = −2.753, p = .006). There were no other significant differences in clinical outcomes between participants who did exhibit increased expression of a given miRNA biomarker and participants who exhibited no change or decreased expression. There were also no significant associations between miRNA expression changes and clinical recovery time or acute symptom severity after SRC.

Discussion

The main finding of our study was significantly upregulated peripheral expression of miR-153–3p, miR-223–3p, and miR-let-7a-5p following sport-related concussion (SRC) in a subset of male and female collegiate athletes. Two other miRNA biomarkers (miR26a-5p and miR-423–3p) showed no change. This is the first investigation of circulating miRNA changes in a concussed sample of athletes, and initial evidence suggests some individuals may differentially express serum miRNA after injury. Most studies of miRNA dysregulation have involved moderate to severe traumatic brain injury (TBI), or unrelated conditions such as cancer, and often use animal models with subsequent histological examinations. Our study uniquely studied miRNA from serum in more mild brain injury samples in vivo while utilizing a within-subject design, but this also limits direct comparisons to existing literature.

Prior studies showed that the five miRNAs examined in this study were associated with aspects of CNS injury, and also described the biological mechanisms these miRNA may modulate post-brain injury. Specifically, miRNA are thought to play a role in signaling the secondary effects of brain injury such as inflammation, apoptosis, and protein expression. The complex neurometabolic cascade associated with SRC involves indiscriminate neurotransmitter release (e.g. potassium efflux, sodium, and calcium influx) along the neuron and a resulting depletion of energy stores (32). Many of these neurophysiological processes underlie the rationale for studying more typical biomarkers of brain injury such as S100 calcium-binding protein B (S100B), ubiquitin carboxy-terminal hydrolase L1 (UCH-L1), and glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), among others. However, differential expression of certain miRNA post-concussion may modulate these pathophysiological reactions and, subsequently, could point the way to therapeutic targets.

The conservation of miRNAs across species and their potential for clinical translational research are among the purported benefits for studying miRNA as brain injury biomarkers. In support of this, the three miRNA exhibiting significantly increased serum expression after SRC in our sample align with several preclinical findings. Liu and colleagues reported miR-153 upregulation in the rat hippocampus following moderate TBI and noted that several of its target genes, such as Snca, are involved in the regulation of cellular activity and synaptic cell surface proteins (10). The Snca gene encodes the alpha-synuclein protein, linking dysregulated miR-153 to Parkinson disease and cognitive dysfunction (33). Data suggest that miR-153 normalizes subacutely following controlled cortical brain injury in younger rodent models (10). MiR-223 is associated with leukocyte activation and inflammation (34,35) and was upregulated throughout rat brain cells following TBI, particularly in microglia and astrocytes and less so in neurons (13). Other studies demonstrated miR-223 upregulation in both rat hippocampal and cortical tissue after TBI (36,37). Secondary effects of CNS trauma are also apparent in rodent spinal cord injury where increased expression of miR-let-7a has been observed (23) up to 1-month post-injury. The miR-let-7 family and its target genes (e.g. RAS and MYC) are reportedly associated with apoptotic signaling, such that increased miR-let-7a expression promotes pro-apoptotic cell responses (38,39).

Taken together, preliminary findings indicate that circulating miRNA potentially signal SRC, but their diagnostic accuracy should be measured against other common concussion biomarkers. We previously evaluated the diagnostic accuracy of beta-amyloid peptide 42 (Aβ−42), total tau, S100B, UCH-L1, and GFAP in an overlapping sample of collegiate athletes measured both at baseline and post-SRC (see Concussion BASICS: Part 3). Descriptively, 69% and 77% of the athletes exhibited elevated (any change) S100B and UCH-L1 after SRC, respectively, compared to 59–70% exhibiting increased expression of the three miRNAs with significant changes in the present study. S100B and UCH-L1 performed better than miRNAs when blood samples were obtained within 4 h of injury (>85% of the athletes increasing post-SRC), suggesting acute serum S100B and UCH-L1 changes relative to baseline may outperform miRNA in detecting SRC.

Sample size limitations precluded firm conclusions regarding the association between changes in miRNA expression post-SRC and clinical outcomes. The correlation coefficients reported in our results may suggest clinically relevant links, but future research with sufficiently powered samples must replicate these findings. MiR-let-7a-5p changes most broadly correlated with clinical outcomes in our study (both cognitive and balance scores). Acute expression of miRNA did not have predictive value for clinical recovery time but, as noted, incorporating additional post-SRC collection points and different miRNAs that may be upregulated in temporal accordance with pathophysiological cascades (10,11) could ultimately improve their utility.

This exploratory study had several limitations. We relied on a small sample of collegiate athletes who sustained an SRC, which may reduce generalizability to other ages and TBI severities. It is unknown what factors beyond brain injury may affect miRNA expression, a particularly important consideration given that a single miRNA can bind with a multitude of target genes with many functional implications. Previous studies incorporated analytic approaches that investigated hundreds of miRNAs simultaneously, while we relied on such studies to inform the rationale for looking at just five potentially relevant miRNAs. Athletes in our sample were distinct from previously studied human populations with histories of moderate to severe TBI. Our study was strengthened by its within-subject design but relied on just one post-injury collection point. Additionally, we cannot speak to specific biological mechanisms underlying pre- to post-SRC changes in miRNA expression or the ultimate relevance of such changes. Other miRNA studies used online prediction programs for identifying target genes potentially regulated by the miRNA of interest, which in turn provides information regarding their functional implications using gene ontology methods. We relied on these previous studies for informing points within our discussion. Further, while 153–3p exhibited significant upregulation from pre- to post-SRC, a high proportion of both baseline and post-SRC samples had an average Ct>30, meaning that these samples had little to no expression of the target miRNA. While it is possible that results were representative of true, but extremely low levels of relative expression, alternative explanations should also be considered. As average Ct values approach 35, it becomes increasingly likely that the particular methodology employed fails to appropriately detect an experimentally sensitive threshold of the target miRNA. Thus, we feel that findings surrounding miR-153–3p should be interpreted cautiously.

Future studies should seek to replicate current findings in a larger sample, focusing on miR-153–3p, miR-223–3p, and miR-let-7a-5p. These studies should be sufficiently powered to examine the relationship between miRNA and a wider breadth of clinical data. In addition, future studies should use in vitro cell lines in order to better understand the role of these specific miRNA in the pathophysiology of concussion, which may, in turn, lead to the development of novel pharmacotherapeutic interventions. Researchers following present methodology for processing of miRNA may expect to detect small relative quantifications, particularly for miR-153–3p and may consider using a detection threshold of Ct>35 rather than 30. In addition, studying miRNAs beyond the few included in the present study might incrementally improve SRC management with regard to diagnosis or prognosis, emphasizing the preliminary nature of the current findings.

Conclusions

MiR-153–3p, miR-223–3p, and miR-let-7a-5p were significantly upregulated acutely following sport-related concussion in male and female collegiate athletes compared to baseline expression, although several athletes demonstrated no change or a decrease in expression. The biological mechanisms and functional implications of the increased expression of these circulating miRNAs are unclear and require more research, as does their relevance to clinical outcomes.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Laura Ranum, PhD (Director, Centre for NeuroGenetics, University of Florida College of Medicine) and Dr. Lien Nguyen, PhD (Postdoctoral Associate, Centre for NeuroGenetics, University of Florida College of Medicine) for providing an independent technical review of the methodology for this study. We also thank Dr. Shelley Heaton, PhD (Clinical Associate Professor, Department of Clinical and Health Psychology, University of Florida), for her determination that the manuscript is free of biased presentation based on her independent review, in accordance with requirements pertaining to the University of Florida’s financial stake in Banyan Biomarkers, Inc.

Disclosure statement

The authors have no relevant disclosure statements pertaining to the equipment, methods, or findings from the current study. BA received partial support from Banyan Biomarkers, Inc., for data collection and analysis. RB reports receiving funding from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (UL1 RR029890) and National Institute of Aging (1Florida Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center; P50 AG047266). SD is supported by the 1Florida ADRC and AG047266. SD also reports serving on advisory boards for Amgen, Cognition Therapeutics, and Acumen, and chairs a Drug Monitoring Committee for Biogen. MJ is supported by McKnight Brain Institute and Florida Department of Elderly Affairs. RH holds stock in and is an employee of Banyan Biomarkers, Inc. JC is supported by Banyan Biomarkers Inc., Florida High Tech Corridor Matching Funds Program, and NCAA-DoD CARE Consortium (Award NO W81XWH-14-2- 0151). RB, AS, and GH report no relevant funding sources.

References

- 1.Kamins J, Bigler E, Covassin T, Henry L, Kemp S, Leddy J,Mayer A, McCrea M, Prins M, Schneider K, et al. What is the physiological time to recovery after concussion? A systematic review. Br J Sports Med. 2017;51(12):935–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McCrea M, Broshek D, Barth J. Sports concussion assessment and management: future research directions. Brain Injury. 2015;29 (2):276–82. doi: 10.3109/02699052.2014.965216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Papa L, Ramia M, Edwards D, Johnson B, Slobounov S. Systematic review of clinical studies examining biomarkers of brain injury in athletes after sports-related concussion. J Neurotrauma. 2015;32(10):661–73. doi: 10.1089/neu.2014.3655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McCrea M, Meier T, Huber D, Ptito A, Bigler E, Debert C, Manley G, Menon D, Chen J, Wall R, et al. Role of advanced neuroimaging, fluid biomarkers and genetic testing in the assessment of sport-related concussion: a systematic review. Br J Sports Med. 2017;51(12):919–29. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2016-097447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Di Pietro V, Ragusa M, Davies D, Su Z, Hazeldine J, Lazzarino G, Hill L, Crombie N, Foster M, Purrello M, et al. MicroRNAs as novel biomarkers for the diagnosis and prognosis of mild and severe traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma. 2017;34(11):1948–56. doi: 10.1089/neu.2016.4857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Friedman R, Farh K, Burge C, Bartel D. Most mammalian mRNAs are conserved targets of microRNAs. Genome Res. 2009;19(1):92–105. doi: 10.1101/gr.082701.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kunej T, Godnic I, Ferdin J, Horvat S, Dovc P, Calin G. Epigenetic regulation of microRNAs in cancer: an integrated review of literature. Mutat Res/Fund Mol Mech Mutagen. 2011;717(1):77–84. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2011.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pauley K, Cha S, Chan E. MicroRNA in autoimmunity and autoimmune diseases. J Autoimmun. 2009;32(3):189–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2009.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bilen J, Liu N, Bonini N. A new role for microRNA pathways: modulation of degeneration induced by pathogenic human disease proteins. Cell Cycle. 2006;5(24):2835–38. doi: 10.4161/cc.5.24.3579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu L, Sun T, Liu Z, Chen X, Zhao L, Qu G, Li Q. Traumatic brain injury dysregulates microRNAs to modulate cell signaling in rat hippocampus. PLoS One. 2014;9(8):e103948. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0103948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hu Z, Yu D, Almeida-Suhett C, Tu K, Marini A, Eiden L, Braga M, Zhu J, Li Z. Expression of miRNAs and their cooperative regulation of the pathophysiology in traumatic brain injury. PLoS One. 2012;7(6):e39357. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Long J, Ray B, Lahiri D. MicroRNA-153 physiologically inhibits expression of amyloid-β precursor protein in cultured human fetal brain cells and is dysregulated in a subset of Alzheimer disease patients. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(37):31298–310. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.366336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang W-X, Visavadiya N, Pandya J, Nelson P, Sullivan P, Springer J. Mitochondria-associated microRNAs in rat hippocampus following traumatic brain injury. Exp Neurol. 2015;265:84–93. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2014.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nakanishi K, Nakasa T, Tanaka N, Ishikawa M, Yamada K, Yamasaki K, Kamei N, Izumi B, Adachi N, Miyaki S, et al. Responses of microRNAs 124a and 223 following spinal cord injury in mice. Spinal Cord. 2010;48(3):192. doi: 10.1038/sc.2009.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen Y, Song Y, Huang J, Qu M, Zhang Y, Geng J, Zhang Z, Liu J, Yang G. Increased circulating exosomal mirna-223 is associated with acute ischemic stroke. Front Neurol. 2017;8. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2017.00057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jia L, Liu Y. Downregulated serum miR-223 servers as biomarker in Alzheimer’s disease. Cell Biochem Funct. 2016;34(4):233–37. doi: 10.1002/cbf.3184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smirnova L, Gräfe A, Seiler A, Schumacher S, Nitsch R, Wulczyn F. Regulation of miRNA expression during neural cell specification. Eur J Neurosci. 2005;21(6):1469–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.03978.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Taheri S, Tanriverdi F, Zararsiz G, Elbuken G, Ulutabanca H, Karaca Z, Selcuklu A, Unluhizarci K, Tanriverdi K, Kelestimur F. Circulating MicroRNAs as potential biomarkers for traumatic brain injury-induced hypopituitarism. J Neurotrauma. 2016;33 (20):1818–25. doi: 10.1089/neu.2015.4281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li -M-M, Jiang T, Sun Z, Zhang Q, Tan -C-C, Yu J-T, Tan L. Genome-wide microRNA expression profiles in hippocampus of rats with chronic temporal lobe epilepsy. Sci Rep. 2014;4:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mitra B, Rau T, Surendran N, Brennan J, Thaveenthiran P, Sorich E, Fitzgerald M, Rosenfeld J, Patel S. Plasma micro-RNA biomarkers for diagnosis and prognosis after traumatic brain injury: A pilot study. J Clin Neurosci. 2017;38:37–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2016.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cogswell J, Ward J, Taylor I, Waters M, Shi Y, Cannon B, Kelnar K, Kemppainen J, Brown D, Chen C, et al. Identification of miRNA changes in Alzheimer’s disease brain and CSF yields putative biomarkers and insights into disease pathways. J Alzheimers Dis. 2008;14(1):27–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sepramaniam S, Tan J-R, Tan K-S, DeSilva D, Tavintharan S, Woon F-P, Wang C-W, Yong F-L, Karolina D-S, Kaur P, et al. Circulating microRNAs as biomarkers of acute stroke. Int J Mol Sci. 2014;15(1):1418–32. doi: 10.3390/ijms15011418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu G, Keeler E, Zhukareva V, Houlé D. Cycling exercise affects the expression of apoptosis-associated microRNAs after spinal cord injury in rats. Exp Neurol. 2010;226(1):200–06. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2010.08.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McCrory P, Meeuwisse W, Dvorak J, Aubry M, Bailes J, Broglio S, Cantu R, Cassidy D, Echemendia R, Castellani R, et al. Consensus statement on concussion in sport—the 5th international conference on concussion in sport held in Berlin, October 2016. Br J Sports Med. 2017. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2017-097699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McCrea M, Kelly J, Randolph C, Kluge J, Bartolic E, Finn G, Baxter B. Standardized assessment of concussion (SAC): on-site mental status evaluation of the athlete. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 1998;13(2):27–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.ImPACT - Manual. [accessed 2017 July 27]. https://www.impacttest.com/dload/ImPACT21_usermanual.pdf.

- 27.Riemann B, Guskiewicz K. Effects of mild head injury on postural stability as measured through clinical balance testing. J Athl Train. 2000;35(1):19. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oride M, Marutani J, Rouse M, Deland P. Reliability study of the Pierce and King-Devick saccade tests. Optom Vis Sci. 1986;63 (6):419–24. doi: 10.1097/00006324-198606000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McCrory P, Meeuwisse W, Aubry M, Cantu B, Dvořák J, Echemendia R, Engebretsen L, Johnston K, Kutcher J, Raftery M, et al. Consensus statement on concussion in sport: the 4th international conference on concussion in sport held in Zurich, November 2012. Br J Sports Med. 2013;47(5):250–58. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2013-092313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grissom R, Kim J. Effect sizes for research: univariate and multivariate applications. 2nd ed. New York: Routledge; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rice M, Harris G. Comparing effect sizes in follow-up studies: ROC area, Cohen’s d, and r. Law Hum Behav. 2005;29(5):615. doi: 10.1007/s10979-005-6832-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Giza C, Hovda D. The new neurometabolic cascade of concussion. Neurosurgery. 2014;75(04):S24. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0000000000000505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Doxakis E Post-transcriptional regulation of α-synuclein expression by mir-7 and mir-153. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(17):12726–34. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.086827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Johnnidis J, Harris M, Wheeler R, Stehling-Sun S, Lam M, Kirak O, Brummelkamp T, Fleming M, Camargo F. Regulation of progenitor cell proliferation and granulocyte function by microRNA-223. Nature. 2008;451(7182):1125. doi: 10.1038/nature06607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Taïbi F, Metzinger-Le Meuth V, Massy ZA, Metzinger L. miR-223: an inflammatory oncomiR enters the cardiovascular field. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis. 2014;1842(7):1001–09. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2014.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lei P, Li Y, Chen X, Yang S, Zhang J. Microarray based analysis of microRNA expression in rat cerebral cortex after traumatic brain injury. Brain Res. 2009;1284:191–201. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.05.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Redell B, Liu Y, Dash K. Traumatic brain injury alters expression of hippocampal microRNAs: potential regulators of multiple pathophysiological processes. J Neurosci Res. 2009;87(6):1435–48. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Johnson M, Grosshans H, Shingara J, Byrom M, Jarvis R, Cheng A, Labourier E, Reinert K, Brown D, Slack F, et al. RAS is regulated by the let-7 microRNA family. Cell. 2005;120(5):635–47. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sampson V, Rong N, Han J, Yang Q, Aris V, Soteropoulos P, Petrelli N, Dunn S, Krueger L. MicroRNA let-7a down-regulates MYC and reverts MYC-induced growth in Burkitt lymphoma cells. Cancer Res. 2007;67(20):9762–70. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]