Abstract

Nintedanib, a tyrosine kinase inhibitor approved for the treatment of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, has anti-fibrotic, anti-inflammatory, and anti-angiogenic activity. We explored the impact of nintedanib on microvascular architecture in a pulmonary fibrosis model. Lung fibrosis was induced in C57Bl/6 mice by intratracheal bleomycin (0.5 mg/kg). Nintedanib was started after the onset of lung pathology (50 mg/kg twice daily, orally). Micro-computed tomography was performed via volumetric assessment. Static lung compliance and forced vital capacity were determined by invasive measurements. Mice were subjected to bronchoalveolar lavage and histologic analyses, or perfused with a casting resin. Microvascular corrosion casts were imaged by scanning electron microscopy and synchrotron radiation tomographic microscopy, and quantified morphometrically. Bleomycin administration resulted in a significant increase in higher-density areas in the lungs detected by micro-computed tomography, which was significantly attenuated by nintedanib. Nintedanib significantly reduced lung fibrosis and vascular proliferation, normalized the distorted microvascular architecture, and was associated with a trend toward improvement in lung function and inflammation. Nintedanib resulted in a prominent improvement in pulmonary microvascular architecture, which outperformed the effect of nintedanib on lung function and inflammation. These findings uncover a potential new mode of action of nintedanib that may contribute to its efficacy in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis.

Keywords: Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, Angiogenesis inhibitors, Intussusceptive angiogenesis, Microvascular corrosion casting, Synchrotron radiation tomographic microscopy

Introduction

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is a disabling, progressive, and ultimately fatal disease characterized by fibrosis of the lung parenchyma and loss of pulmonary function [1]. IPF is believed to be caused by repetitive alveolar epithelial cell injury and dysregulated repair, with uncontrolled proliferation of pulmonary fibroblasts and their differentiation into myofibroblasts. These myofibroblasts deposit excessive amounts of extracellular matrix components in the interstitial space [2]. A number of pro-fibrotic mediators, including platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) [3], fibroblast growth factors (FGFs) [4], and transforming growth factor (TGF)b [5], play important roles in the pathogenesis of IPF. Pathologic angiogenesis appears to be intrinsically associated with fibrogenic progression in pulmonary fibrosis, but it is unclear how morphological neovascularization correlates with the progression of fibrosis.

Nintedanib is a potent inhibitor of the receptor tyrosine kinases FGF receptor-1, −2, −3, PDGF receptor a/b, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) receptor-1, −2, −3, and Flt-3 and of non-receptor tyrosine kinases like Src, Lyn, and Lck, which occupy the intracellular ATP-binding pocket [6]. In primary lung fibroblasts from patients with IPF, nintedanib inhibited growth factor-stimulated migration and proliferation [7] and attenuated TGFb-induced transformation to myofibroblasts [8].

The in vivo efficacy of nintedanib was explored in silica-induced lung fibrosis in mice and bleomycin-induced lung fibrosis in mice and rats [9]. Nintedanib exerted significant anti-fibrotic and anti-inflammatory activity. Nintedanib suppressed transcript levels of central fibrosis-related genes (TGFb1, procollagen 1) and total collagen levels and reduced the fibrotic score in histomorphometric analyses of fibrotic lungs. Nintedanib reduced the levels of lymphocytes in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF), diminished levels of inflammatory mediators (IL-1β, IL-6, CXCL1/KC) and the percentage of myeloid dendritic cells in lung tissue, and reduced pulmonary inflammation and granuloma formation [9].

Preclinical studies have shown that inhibition of VEGF, PDGF, and FGF signaling pathways reduces tumor angiogenesis in the lung [10]. The potential impact of anti-angiogenic activity in the treatment of IPF has not been clarified [11]. Nintedanib inhibits proliferation of endothelial cells, pericytes, and smooth muscle cells, where it inhibits the proliferation of VEGF-stimulated human umbilical vein endothelial cells, PDGF-BB-stimulated human umbilical artery smooth muscle cells, and PDGF-BB-stimulated bovine retinal pericytes [6]. Nintedanib also demonstrated anti-angiogenic efficacy in a mouse model of xenograft tumors [6]. The objective of this study was to explore the pulmonary vascular alterations in the mouse model of bleomycin-induced lung fibrosis and the impact of nintedanib on the remodeled microvascular architecture.

Materials and methods

Animals

C57/BL6 mice (Charles River, Sulzfeld, Germany) aged 8–12 weeks, weighing 22–30 mg, were used in all experiments. The care of the animals was consistent with guidelines of the German Federal Association for Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care.

Bleomycin model and treatment

Induction of bleomycin-induced lung fibrosis, compound treatment, and animal housing were carried out according to standardized procedures.

Animals were short-term anesthetized with isoflurane (3–5%). Bleomycin (Calbiochem, Darmstadt, Germany) at a dose of 0.5 mg/kg (1.5–2 U/mg) in sterile isotonic saline (50 μL per animal) was intratracheally instilled by means of a 22 gauge plastic cannula (Vasofix, 0.5 × 25 mm, B. Braun Melsungen, Germany) coupled to a 1-mL syringe. Mice in the vehicle group were given the same volume of sterile saline.

Treatment with nintedanib was started 7 days after bleomycin instillation by twice daily oral (by gavage) administration of 50 mg/kg (hydroxyethylcellulose [Natrosol®] suspension 0.5%) and continued until day 19 after bleomycin application.

Experimental setup

On day 19, lung density was assessed by micro-computed tomography (lCT) analysis. On day 20, final analyses were conducted. Lung function was determined in all animals. Half of the animals were subjected to bronchoalveolar lavage, tissue sampling for histology/immunohistochemistry, and tissue sampling for hydroxyproline analysis and mRNA analysis. The other half were subjected to vascular corrosion casting and synchrotron radiation tomographic microscopy (SRXTM).

Assessment of lung function

Mice were anesthetized with pentobarbital 48 mg/kg combined with xylazine 2.32 mg/kg injected i.p. After tracheostomy and intubation, the tracheal cannula was connected to a FlexiVent system (SCIREQ, Montreal, PQ, Canada) for pulmonary function testing. To prevent spontaneous breathing, animals received pancuronium bromide 0.64 mg/kg i.v. (Inresa Arzneimittel GmbH, Freiburg, Germany). Ventilation was conducted with 150 breath/min, a tidal volume of 10 mL/kg, and an end-expiratory pressure of 3 cm H2O. After recruiting total lung capacity (30 cm H2O), dynamic lung compliance and forced vital capacity were measured. Static compliance was determined by generating pressure volume loops with a maximal plateau pressure of 30 cm H2O.

μCT

Animals were anesthetized with isoflurane 1.5% and fixed in the prone position. μ-CT images were acquired with a Quantum FX lCT system (Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA, USA) with cardiac gating (without respiratory gating), using the following parameters: 90 kV; 160 μA; FOV, 60 × 60 × 60 mm; spatial resolution 0.11 mm, resulting in a total acquisition time of 4.5 min. Images were analyzed using MicroView 2.0 software (GE Healthcare, Amersham, UK), which allows a semiautomatic segmentation of the lungs. Hounsfield unit (HU) histograms were obtained for the left and right lungs using bins of 10-HU width. In the absence of a well-established standard to quantify fibrotic changes in rodents with μCT, and to avoid relying on an arbitrary threshold to identify fibrotic regions [12, 13], the HU corresponding to the peak of the HU-histogram for the segmented pixels was used as a measure of fibrosis. Total lung volume was computed.

Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF)

Mice were killed by intraperitoneal injection of pentobarbital (400 mg/kg, Narcoren, Merial GmbH, Halbergmoos, Germany). The left bronchus was sealed by a ligature, and the right lung was lavaged twice with 400 μL PBS. Total cell count of BAL cells and differential cell count were determined by means of a Sysmex XT1800 iVet cell analyzer (Sysmex Europe GmbH, Norderstedt, Germany).

Histochemistry and immunohistochemistry

Analysis and quantitation of cellular proliferation (anti-Ki67, Clone TEC-3, Dako, Hamburg, Germany) was performed using immunohistochemistry. Cross sections of the left lung lobe were harvested, formalin fixed, and embedded in paraffin. Three microscopic fields at 40× magnification were used. Picrosirius red staining was used to compare the collagen content of fibrotic foci with normal tissue.

Ashcroft score

Fibrotic changes in each lung section were assessed as the mean score of severity from observed microscopic fields [14]. More than 25 fields within each lung section were observed at a magnification of 100×. Scores from 0 (normal) to 8 (total fibrosis) were assigned using a predetermined scale. After examination of the whole section, the mean of the scores from all fields was taken as the fibrotic score.

Hydroxyproline analysis

Whole collagen content of the right lung was quantified colorimetrically using an assay of hydroxyproline. The lung tissue was hydrolyzed with 1 mL 6 N HCl (Amresco, OH, USA) at 110°C for 16 h. Triplicates of 5 μL of the supernatant were placed in a 96-well plate and mixed with 50 μL 0.1 M citrate buffer, pH 6.0, and 100 μL 150 mg chloramine T (Sigma-Aldrich, Darmstadt, Germany) dissolved in citrate buffer (0.1 M, pH 6.0; Sigma-Aldrich) an incubated at room temperature for 20 min. Next, 100 μL of cooled Ehrlich’s (1.25 g distilled water-dissolved dimethylbenzaldehyde; Sigma-Aldrich) was added to the reaction mixture and incubated at 65°C for 30 min. Absorbance was measured at 550 nm in an Infinite M200Pro spectrophotometer (TECAN, Wiesbaden, Germany). Total hydroxyproline (lg/lung weight) was calculated on the basis of individual lung weights and the corresponding relative hydroxyproline content.

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction

Relative messenger RNA (mRNA) levels were quantified in total lung RNA by reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction on a LightCycler 1.5 instrument (Roche, Mannheim, Germany) using the TaqMan methodology (Roche, Indianapolis, IN, USA). Total RNA was isolated with TRIzol Reagent (Sigma-Aldrich), and 1 lg total RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA using the iScript cDNA Synthesis Kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). TaqMan reaction mixtures were purchased from Applied Biosystems. Gapdh mRNA was used to normalize data and to control for RNA integrity. TaqMan reactions were performed using a Step One Plus sequence amplification system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). The results were expressed as the ratio of the copy number of the target gene divided by the number of copies of the housekeeping gene (Gapdh) within the polymerase chain reaction run.

Quantitative reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction primers:

Acta2, forward 5′-ACAGCCCTCGCACCCA-3′, reverse 5′-CAAGATCATTGCCCCTCCAGAACGC-3′, probe 5′-GCCACCGATCCAGACAGAGT-3′; Ifng, forward 5′-CAGCAACAGCAAGGCGAAA-3′, reverse 5′-CTGGACCTGTGGGTTGTTGAC-3′, probe 5′-TCAAACTTGGCAATACTCATGAATGCATCCT-3′; Mmp2, forward 5′-CCGAGGACTATGACCGGGATAA-3′, reverse 5′-CTTGTTGCCCAGGAAAGTGAAG-3′, probe 5′-TCTGCCCCGAGACCGCTATGTCCA-3′; Mmp3, forward 5′-GATGAACGATGGACAGAGGATG-3′, reverse 5′-TGGTACCAACCTATTCCTGGTTGCTGC-3′, probe 5′-CAGAGAGTTAGATTTGGTGGGTACCA-3′; Col1a1, forward 5′-TCCGGCTCCTGCTCCTCTTA-3′, reverse 5′-GTATGCAGCTGACTTCAGGGATGT-3′, probe 5′-TTCTTGGCCATGCGTCAGGAGGG-3′; Tgfb1 forward 5′-AGAGGTCACCCGCGTGCTAA-3′, reverse 5′-ACCGCAACAACGCCATCTATGAGAAAACCA-3′, probe 5′-ACCGCAACAACGCCATCTATGAGAAAACCA-3′; and Timp1, forward 5′-TCCTCTTGTTGCTATCACTGATAGCTT-3′, reverse 5′-CGCTGGTATAAGGTGGTCTCGTT-3′, probe 5′-TTCTGCAACTCGGACCTGGTCATAAGG-3′; Tnfa, forward 5′-GGGCCACCACGCTCTTC-3′, reverse 5′-GGTCTGGGCCATAGAACTGATG-3′, probe 5′-ATGAGAAGTTCCCAAATGGCCTCCCTC-3′ were purchased from Eurofins Genomics.

Quantitative vessel architecture analysis by microvascular corrosion casting

After systemic heparinization with 2000 U/kg heparin i.p., mice were thoracotomized under deep anesthesia. The pulmonary artery was cannulated through the right ventricle with an olive-tipped cannula and perfused with 10 mL saline at 37°C followed by 10 mL of a buffered 2.5% glutaraldehyde solution (Sigma) at pH 7.4. After casting the microcirculation with 10 mL of polyurethane-based casting resin PU4ii (vasQ-tec, Zurich, Switzerland) and caustic digestion, the microvascular corrosion casts were imaged after coating with gold in an argon atmosphere with a Philips ESEM XL30 scanning electron microscope. From each lung series of stereopairs with tilt angles of 6° were made for quantitative analyses. The stereopairs were color coded and reconstructed as anaglyphic images. With the known tilt angle, calculations of individual points marked interactively in both images of each stereopair were carried out using macros defined for the Kontron KS 300 software (Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany). For definition of the dimensions of the microvascular unit, the intervascular distances as well as the vessel diameters and the variability of the vessel diameters were assessed in the fibrotic areas only for comparative purposes and depicted as cumulative percentage.

Qualitative vessel architecture analysis by microvascular corrosion casting

Analysis of microvascular corrosion casts was used to assess the effects of nintedanib on the vascular architecture. Features of intussusceptive angiogenesis, a rapid mode of vasculature expansion, were identified in the vascular cast as tiny holes (hallmarks of intussusceptive pillars) and small capillary loops with diameters between 2 and 5 lm. The effect of nintedanib (+Bleo +Nint) on fibrotic capsula and foci was compared with a vehicle group (not treated with bleomycin, -Bleo) and a positive control group (treated with bleomycin but not nintedanib, +Bleo).

Synchrotron radiation tomographic microscopy (SRXTM)

The samples were scanned at an X-ray wavelength of 1Å (corresponding to an energy of 12.398 keV) at the microtomography station of the Materials Science Beamline at the Swiss Light Source of the Paul Scherrer Institut (Villigen, Switzerland). The monochromatic X-ray beam (ΔE/E = 0.014%) was tailored by a slits system to a profile of 1.4 mm2. After penetration of the sample, X-rays were converted into visible light by a thin Ce-doped YAG scintillator screen (Crismatec Saint-Gobain, Nemours, France). Projection images were further magnified by diffraction-limited microscope optics and finally digitalized by a high-resolution CCD camera (Photonic Science, East Sussex, UK). For the tissue samples, the optical magnification was set to 20×, and vascular casts were scanned without binning with an optical magnification, resulting in a voxel size 0.325 μm3. For each measurement, 1001 projections were acquired along with dark and periodic flat field images at an integration time of 4 s each without binning. Data were postprocessed and rearranged into flat field-corrected sinograms online. Reconstruction of the volume of interest was performed on a 16-node Linux PC Farm (Pentium 4, 2.8 GHz, 512 megabytes RAM) using highly optimized filtered back-projection. A global thresholding approach was used for surface rendering. For 3D visualization and surface rendering, Amira software (Burlington, MA, USA) was installed on an Athlon 64 3500-based computer. The 3D visualizations were analyzed with the program Avizo Fire 7.0.

Transmission electron microscopy

Fibrotic foci were analyzed by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) to detect the potential role of alveolar type II cells and alveolar macrophages in the healing process. Samples designated for TEM were fixed with 2.5% buffered glutaraldehyde and embedded in Epon (Serva, Heidelberg, Germany). 700-Å ultrathin sections were analyzed using a Leo 906 digital transmission electron microscope (Leo, Oberkochen, Germany).

Statistics

All data are presented as mean ± standard deviation of n animals. Statistical differences between groups were analyzed by paired t test, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with subsequent Dunnett’s multiple comparison test for all parametric data and Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Dunn’s multiple comparison test for nonparametric data (GraphPad Prism 6.0; GraphPad Software, Inc. La Jolla, CA, USA), and p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Nintedanib induces a trend toward improved lung function

Twenty days after bleomycin administration, dynamic lung compliance, forced vital capacity (FVC), and static lung compliance were significantly decreased compared with mice treated with vehicle (Table 1). Nintedanib resulted in a trend toward improved lung function with respect to FVC (~20% improvement) (Table 1), static lung compliance (~25% improvement) (Table 1; Fig. 1a) which did not reach statistical significance. This trend was also recorded in an experiment conducted in preparation for this study (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Table 1.

The effect of nintedanib on lung function

| Vehicle without bleomycin | Bleomycin | Bleomycin + nintedanib | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD (n = 15) | Mean | SD (n = 24) | Mean | SD (n = 24) | |

| Cdyn (mL/cm H2O) | 0.043 | ±0.0022 | 0.034 | ±0.0061* | 0.034 | ±0.0065 |

| FVC (mL) | 1.14 | ±0.071 | 0.95 | ±0.13* | 0.99 | ±0.13 |

| Cstat (mL/cm H2O] | 0.026 | ±0.0016 | 0.020 | ±0.0032* | 0.022 | ±0.0032 |

Lung function tests were conducted invasively at the end of the experiment (day 20). Pathology was induced by intratracheal administration of bleomycin. Nintedanib treatment was conducted from day 7 to day 19 (50 mg/kg b.i.d.)

Cdyn, Dynamic lung compliance; FVC, forced vital capacity; Cstat, static lung compliance, calculated at an applied inflation pressure of 30 cm H2O

p < 0.0001 versus vehicle without bleomycin

Fig. 1.

Functional lung testing showed that nintedanib was associated with a trend toward improved lung function and a reduced proliferative activity. a Functional lung testing. Pressure volume loops were conducted with an inflation pressure of up to 30 cm H2O. Data are mean ± standard error of the mean. Vehicle group without bleomycin stimulation (-Bleo), n = 13, positive control animals stimulated with bleomycin 0.5 mg/kg (+Bleo), n = 24, bleomycin-stimulated animals treated with nintedanib 50 mg/kg twice daily from day 7 until day 19 (+Bleo +Nint), n = 23. b Tissue density assessed volumetrically by μCT. The ratio between the volume of the dense fibrotic tissue and the total lung volume (F/L) is presented. Vehicle group without bleomycin stimulation (-Bleo), n = 18, positive control animals stimulated with bleomycin (+Bleo), n = 24, bleomycin-stimulated animals treated with nintedanib 50 mg/kg twice daily (+Bleo +Nint), n = 24; ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001. c Quantitative assessment of interstitial pulmonary fibrosis was carried out based on the standardized histopathologic quantification according to Ashcroft. Treatment with nintedanib (?Bleo ?Nint) resulted in a significant reduction of the fibrosis grade compared with bleomycin-stimulated lungs (+Bleo); ***p < 0.001. d Quantification of anti-Ki-67-positive cells showed that treatment with nintedanib significantly reduced proliferation rate. Data are mean ± standard error of the mean (-Bleo), n = 12, (+Bleo), n = 12, (+Bleo +Nint), n = 12; ***p < 0.001

Nintedanib reduces fibrotic density and bleomycin-induced lung inflammation

Administration of bleomycin significantly increased lung tissue density assessed by μCT, whereas treatment with nintedanib significantly reduced the ratio of dense fibrotic tissue to total lung volume by 78% (Fig. 1b, p < 0.001). These findings were in line with the histopathologic analysis of fibrotic tissue illustrated by Azan- and Sirius red-positive areas (Fig. 2). The histopathologic quantification of fibrosis grade using the Ashcroft score revealed a significant reduction in fibrotic areas with nintedanib (2.08 ± 1.99, p < 0.001) compared with animals treated with bleomycin only (positive controls) (4.89 ± 1.19), while vehicle-treated animals had an Ashcroft score of 0.03 ± 0.16 (Fig. 1c). Remarkably, hydroxyproline content was not different between the positive controls and the nintedanib-treated animals (not shown). Bleomycin-instilled mice showed elevated levels of mRNA expression of procollagen α1 (p < 0.001), TGFβ1 (p < 0.01), TIMP-1 (p < 0.001) and MMP-2 (p < 0.001) (Fig. 3). Nintedanib reduced the protein expression of TGFb1 (p < 0.05), MMP-2 (p < 0.001), and TIMP-1 (p = ns). Surprisingly, bleomycin treatment reduced the expression of alpha smooth muscle actin (ACTA2; Supplemental Fig. 2). The expression of MMP-3, IFNc, and TNFα was not significantly different between the positive controls and nintedanib-treated mice (Supplemental Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Increased tissue density and fibrotic foci was readily recognized in lower-resolution analysis of Azan- and Sirius-red stained sections in positive controls (+Bleo). The grade of fibrosis in nintedanib-treated animals was reduced (+Bleo +Nint). Bars 200 μm

Fig. 3.

The expression of pro-fibrogenic, fibrolytic and pro-inflammatory transcripts in bleomycin-treated lungs (+Bleo). Relative lung mRNA transcript levels of a procollagen α1(I), b TGFβ1 (transforming growth factor-β1), c TIMP-1 (tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1), and d MMP-2 (matrix metalloproteinase isoform 2) were determined by quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction. Data are mean ± standard deviation. The x-fold increase in expression normalized to the expression in the vehicle group (-Bleo) is presented. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001

Nintedanib reduces the amount of inflammatory cells and suppresses proliferation

Cell proliferation was assessed by morphometric analysis of anti-ki67-stained sections (Supplemental Fig. 3). In animals not treated with bleomycin, 5.2 ± 5.6 positive stained nuclei per field of view (FOV) were detected, mainly attributed to the self-renewal of cells like alveolar macrophages or alveolar epithelial type II cells. Bleomycin-stimulated animals had an average proliferation rate of 96.4 ± 35.0 positive cells per FOV, which was nearly 20-fold higher than in the vehicle group. Treatment with nintedanib resulted in a significant 63% reduction of this proliferative activity (35.3 ± 20.4 positive stained cells per FOV) (Fig. 1d). All differences reached statistical significance (p < 0.001).

Bleomycin caused a significant increase in total cells (Fig. 4a), monocytes (Fig. 4b), and lymphocytes (Fig. 4c) measured in the BALF, whereas neutrophil counts remained low (Fig. 4d). Nintedanib decreased the total cell count in BALF by 46% and reduced the monocyte and lymphocyte cell counts by 57% (Fig. 4b) and 46% (Fig. 4c), respectively.

Fig. 4.

Flow cytometric evaluation of bronchoalveolar lavage fluid. Cytometry of BALF showed that treatment with nintedanib had striking effects on the amount of inflammatory cells. Treatment with nintedanib resulted in a trend toward reduced cell counts. Total cell count: The total cell count (a) was reduced by 46%. Inflammatory cells: The monocyte (b) and lymphocyte (c) counts were halved, whereas neutrophils (d) were not affected by nintedanib. Data are mean ± standard error of the mean. Vehicle group without bleomycin stimulation (-Bleo), n = 9, positive control animals stimulated with bleomycin (+Bleo), n = 12, bleomycin-stimulated animals treated with nintedanib 50 mg/kg twice daily (+Bleo +Nint), n = 12; **p < 0.01

Nintedanib improves and largely normalizes the microvascular architecture

Qualitatively, bleomycin stimulation reduced the integrity of the alveolar morphology. Instead of perialveolar baskets, large areas with densely packed vessel bulks in the fibrotic foci, and a higher vascular density, especially in the foci, were observed. There was no hierarchy of the vascularity, but, instead, a chaotic tumor vessel-like arrangement with tortuous vessel courses and numerous blind-ending vessels (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Nintedanib restored a “normal” pulmonary vascular architecture. Scanning electron micrographs of microvascular corrosion casts illustrate the striking architectural differences between the positive control animals stimulated with bleomycin (+Bleo) and the bleomycin-stimulated animals treated with nintedanib (+Bleo +−Nint). The microvascular architecture of the lungs of animals treated with nintedanib was characterized by a recurrence of alveolar basket structure, whereas the lungs of the positive controls showed huge areas with densely packed vessel bulks constricting the airway system. Bars 200 μm

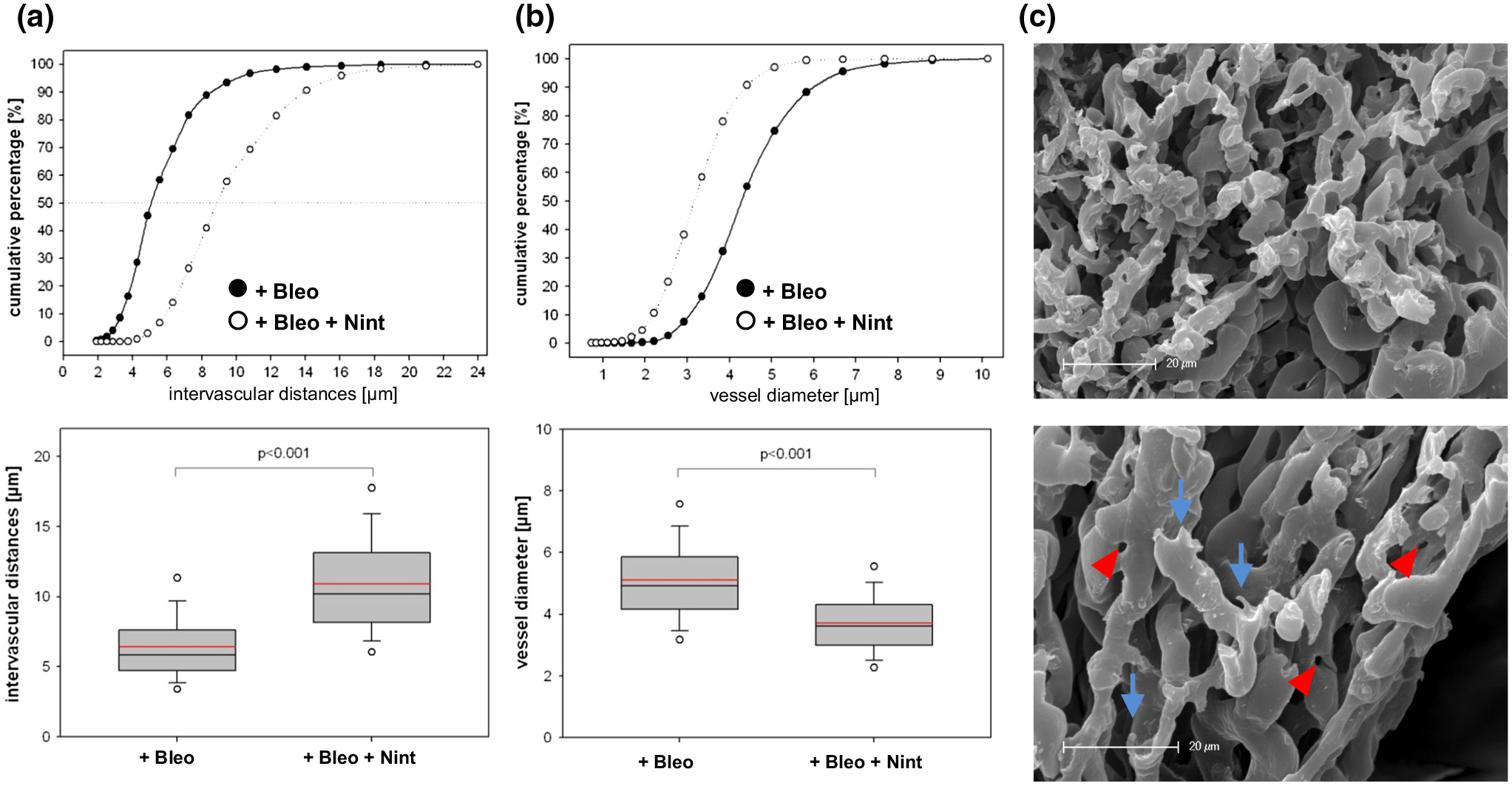

The mean intervessel distance in the positive controls was 6.43 ± 2.58 μm, whereas nintedanib-treated animals showed a mean intervessel distance of 10.89 ± 3.71 μm, indicating significantly lower vessel densities (Fig. 6a, p < 0.001). The individual vessel diameters were assessed in the vessels of fibrotic lesions. The vessels in bleomycininstilled lungs had a mean vessel diameter of 5.1 ± 1.38 lm in the foci, whereas the bleomycin-stimulated, nintedanib-treated animals showed a mean vessel diameter of 3.71 ± 1.0 μm (p < 0.001) (Fig. 6b), indicating a normalizing effect of nintedanib on the microvascular architecture in the fibrotic lesions.

Fig. 6.

Nintedanib normalized microvascular architecture as assessed by 3D-morphometry. Intervascular distances (a) and vessel diameters (b) in fibrotic foci assessed tridimensionally in microvascular corrosion casts shown as cumulative frequencies and box-whisker plots with the median, 5th, 10th, 25th, 75th, 90th, and 95th percentiles; mean (red). All p values were significant (p < 0.001). c Scanning electron micrographs of a fibrotic bleomycin lung (+Bleo). Vascular casts showing a chaotic tumor-like vasculature with sprouting angiogenesis (blue arrows). Adjacent to the bronchi are intussusceptive pillars (red arrowheads), hallmarks of intussusceptive angiogenesis. Lungs from positive controls stimulated with bleomycin (+Bleo), n = 12, bleomycin-stimulated animals treated with nintedanib 50 mg/kg twice daily (+Bleo +Nint), n = 14. Bars 20 μm.

Sprouting and intussusceptive angiogenesis as a driver of fibrotic neovascularization

Altered vascular architecture occurred predominantly in the subpleural and peribronchial regions in bleomycin-treated mice, whereas the vehicle group showed intact lung architecture (Fig. 7a, b). SRXTM qualitatively confirmed that the lungs of bleomycin-treated animals had reduced integrity of the alveolar morphology with densely packed vessel bulks (Fig. 7c, d). Microvascular corrosion casting revealed the appearance of both forms of angiogenesis, namely sprouting angiogenesis depicted as small protrusions (Figs. 6c [blue arrows], 7d [red squares]) and the fast adapting—shear stress and flow dependent—intussusceptive angiogenesis (Figs. 6c [red arrowheads], 7d [yellow circles]). The lungs of mice treated with bleomycin and nintedanib also revealed a lack of regular vascular hierarchy, but to a far lower extent (Fig. 7e). The microvascular architecture in the lungs of nintedanib-treated mice resembled normal, autochthonous vascular lung architecture with alveolar plexus (Fig. 7f); the diameters of the individual vessel segments showed little variation, whereas the lungs of mice treated with bleomycin alone were characterized by large caliber, sinusoidal vessel networks with frequent vessel diameter changes (see supplemental movies).

Fig. 7.

Sprouting and intussusceptive angiogenesis play a pivotal role in fibrogenesis shown in SRXTM. a Three-dimensional evaluation of microvascular corrosion casts by SRXTM illustrating the regular alveolar duct structure accompanied by the limiting alveolar entrance ring vessels. Bars 75 lm. b A typical example of vasculature in the basket-shaped alveoli. Bars 30 μm. c Analysis of the fibrotic lungs of bleomycin-stimulated animals revealed an increased, irregular vascularity with loss of tissue integrity and double-layered vessels. Bars 60 μm. d In fibrotic lungs intussusceptive holes (yellow circles) were found, indicative of the occurrence of intussusceptive angiogenesis around larger vessel structures. Several angiogenic sprouts are highlighted with a red square. e In the lungs of animals treated with nintedanib, the vascular density was decreased and regular alveolar patterns were observed. Bars 50 μm. f After nintedanib treatment, the alveolar entrance ring vessels (dashed red line) defining the alveolar opening were predominantly found in the remodeled tissue reenabling the blood-gas exchange. Bars 30 μm (see movies in supplemental material).

Nintedanib alleviates collagen accumulation and restores alveolar structure

Semithin sections of alveolar tissue demonstrated an accumulation of type II pneumocytes (Fig. 8a). Ultrastructural analyses by TEM revealed striking morphologic differences between nintedanib- and vehicle-treated lungs (Fig. 8b–d). At first glance, huge masses of mature-type striated collagen fibrils were found in bleomycin- and vehicle-treated animals, especially in the vicinity of the bronchial system (Fig. 8b). As an inflammatory, desmoplastic envelope, we observed inflammatory cells (neutrophils, lymphocytes) framing the huge masses of chaotically arranged collagen fibers (Fig. 8b). Occasionally, marginalized fibroblasts revealed high-secreting activity demonstrated by a high content of rough endoplasmic reticulum (Fig. 8b). The orientation of the collagen fibers appeared highly divergent, and around the focal accumulation of collagen fibers, high densities of vessels with capillary wall building were seen (Fig. 8c). The lungs of nintedanib-treated mice did not display the large bulks of collagen fibers seen in the lungs of vehicle-treated, bleomycin-stimulated animals (Fig. 8d), and the collagen bundles appeared looser and more degraded (Fig. 8e).

Fig. 8.

Lung ultrastructure revealed therapeutic effects of nintedanib. a Semithin sections of a bleomycin-treated alveolar tissue showing loss of normal alveolar architecture with thickened interalveolar septa and an increased number of type II pneumocytes (yellow asterisks), bars 50 μm. b Transmission electron micrographs illustrating the close interaction of collagen deposition, fibroblasts, and inflammatory cells in bleomycin-treated mice. fibr fibroblasts, bars 10 μm. c In bleomycin-treated mice, a bulk of densely packed, thin capillaries were observed constricting alveolar space, bars 5 μm. d Nintedanib-treated animals did not display this huge mass of differentiated collagen fibers, bars 10 μm. e Collagen fibers appeared looser and more degraded in nintedanib-treated mice, bars 2 μm. Capillaries, c.

Discussion

The present study investigated the effects of the tyrosine kinase inhibitor nintedanib on three-dimensional morphogenetic evidence of angiogenesis in an animal model of lung fibrosis, compared with conventional parameters of angiogenesis and fibrosis.

First, treatment with nintedanib resulted in a trend toward improved lung function and a reduction in inflammatory cells in the BALF. Second, lung tissue density, assessed by lCT and histopathologic Ashcroft score, was significantly improved by nintedanib, in line with a reduction in proliferative activity. Third, nintedanib had positive effects on microvascular architecture, increasing intervascular distances and reducing vessel diameters. Data obtained using SRXTM suggest a role for sprouting and intussusceptive angiogenesis in alveolar tissue neoalveolarization on a sub-micron level. Finally, ultrastructural analysis revealed a reduction in the bulk of collagen bundles and an increase in activated macrophages and type 2 cells with nintedanib.

Functional testing of lung parameters revealed a trend toward a better outcome with nintedanib. Clinical trials have confirmed that nintedanib slows disease progression in patients with IPF by significantly reducing the decline in FVC [15, 16]. The limited effect of nintedanib observed in this study might be explained by the study design, with a relative short treatment duration and early tissue harvesting limiting the time for alveolar restoration. The main experimental limitation of the bleomycin animal model is that bleomycin only causes an inflammatory response that is triggered by the overproduction of free radicals and pro-inflammatory cytokines [17], and the development of fibrosis remains partially reversible [18].

Our analysis of BALF showed an increased number of monocytes and lymphocytes in bleomycin-treated animals, whereas nintedanib reduced the number of these cells. Macrophages are critical drivers of fibrogenesis by promoting inflammation and angiogenesis [19, 20], and recent evidence suggests a role for activated macrophages in acute exacerbations of IPF [21]. Our recent flow cytometry data in compensatory lung regeneration confirm the active contribution of macrophages and local alveolar type II cells to alveolar growth in neoalveolarization and neovascularization [22, 23].

Nintedanib is a potent inhibitor of the VEGF receptor, FGF receptor, and PDGF receptor [6, 24], which trigger pro-angiogenic signaling in lung fibrosis [25, 26]. In the present study, treatment with nintedanib almost normalized the vascular architecture, with restoration of alveolar basket structures in fibrotic lungs. This finding of architectural restoration is in line with the improved lung function in mice and in patients with IPF [15, 16, 27]. In clinical trials, nintedanib reduced the decline in FVC independent of the severity of lung function impairment at baseline [27].

The reciprocal interaction between endothelial cells, macrophages, and fibroblasts stimulates the fibrotic cascade proceeding from the initial epithelial damage to the excessive deposition of extracellular matrix [28, 29]. The loss of integrity of the basement membrane and alveolar–capillary membrane enables the continuous destruction of lung architecture by pro-angiogenic and pro-fibrotic stimuli. Thus, fibroblasts from patients with IPF express higher levels of PDGF receptors and FGF receptors than controls [7]. Nintedanib prevents the pro-proliferative and fibrotic effects triggered by PDGF-BB, bFGF, and VEGF [7, 8]. Hilberg et al. [6] demonstrated that nintedanib inhibited the proliferation of three cell types contributing to tumor angiogenesis (endothelial cells, pericytes, and smooth muscle cells) in epithelial lung carcinoma cell lines, emphasizing the anti-proliferative and anti-angiogenic potency of nintedanib.

Intussusceptive angiogenesis plays a pivotal role in various proliferative diseases [30–32]. Our study is the first, to our knowledge, to demonstrate a role for intussusceptive angiogenesis in fibrogenesis, as imaged by scanning electron microscopy and SRXTM. These methods allowed a high-definition display of vessel morphology, providing 3-D detail down to the capillary level [33]. Mechanical stress and related changes in blood flow are thought to play pivotal roles in the initiation of intussusceptive remodeling. We have shown a rapid upregulation of intussusceptive vessel expansion in a model of compensatory lung growth after pneumonectomy [33]. Intussusceptive angiogenesis is distinct from sprouting angiogenesis because it has no requirement for cell proliferation, can rapidly expand an existing capillary network, and can maintain organ function during replication and remodeling. Thus, this pillar formation and branch remodeling may represent an adaptive response to the increasing blood flow and blood pressure during inflammation and regeneration. The occurrence of intussusceptive angiogenesis is related to the homing and mobilization of endothelial precursor cells from the bone marrow or the peripheral blood integrating and lining the endothelial wall [30]. Interestingly, clinical findings have shown an imbalance of circulating and proliferating endothelial progenitor cells in patients with IPF, with enhanced endothelial progenitor cell mobilization into the pulmonary vasculature [34]. This homing may be associated with the recurrence of intussusceptive angiogenesis. However, recent studies have suggested that recruitment of circulating fibrocytes occurs [29, 35]. These circulating fibrocytes are a subpopulation of bone marrow hematopoietic-derived cells characterized by the expression of procollagen type I and hematopoietic markers, such as CD45 and CD34 [35]. The relative contribution of circulating fibrocytes and endothelial progenitor cells to the aggravation of pulmonary fibrosis remains to be determined.

Notably, nintedanib treatment led to the development of near-normal lung vasculature likely to restore the delicate blood-gas exchange. Although excessive extracellular matrix substantially accounts for the decline of lung function in pulmonary fibrosis, microvascular remodeling as irregularly shaped capillaries and/or the increase in alveolar–capillary diameters further attenuates blood-gas exchange [36]. In addition to vascular architectural changes, pulmonary capillary endothelial cells might serve as a source of fibroblasts in pulmonary fibrosis via endothelial–mesenchymal transition [37]. Taken together, the changes in microvascularity may be considered a decisive morphogenetic factor in the aggravation of pulmonary fibrosis.

In summary, this study provides the first evidence that the anti-angiogenic activity of nintedanib restores the integrity of lung architecture in pulmonary fibrosis. Our findings suggest that pulmonary fibrogenesis and neoangiogenesis interact in the progression of pulmonary fibrosis. Nintedanib might interfere with these pivotal pathogenetic mechanisms in pulmonary fibrosis, significantly improving lung function and normalizing the microvascular architecture. Further work is necessary to illuminate the dynamic capillary–alveolar interactions between structural adaptations of the microvascular architecture and inflammation in pulmonary fibrosis using SRXTM.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work is dedicated to the memory of the late Prof. Moritz A. Konerding. The authors acknowledge the skillful technical assistance of Kerstin Bahr (University Medical Center Mainz), Janine Beier, Helene Lichius, and Andrea Vögtle (all Boehringer Ingelheim, Biberach). Editorial assistance, funded by Boehringer Ingelheim, was provided by Clare Ryles of Fleishman-Hillard Fishburn. M.A., L.W., M.A.K., D.Sc., and S.J.M were involved in the conception and design. M.A., Y.O.K., W.L.W., C.D.V., S.K., D.St., and L.W. were involved in the experimental work, analysis, and interpretation. M.A., Y.O.K., W.L.W, C.D.V., D.Sc., S.J.M., S.K., D.St., and L.W. drafted the manuscript and revised it for intellectual content. M.A. is the guarantor of this work and, as such, had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Funding This study was funded in part by Boehringer Ingelheim, Biberach, Germany

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s10456-017-9543-z) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

References

- 1.Raghu G, Collard HR, Egan JJ, Martinez FJ, Behr J, Brown KK, Colby TV, Cordier JF, Flaherty KR, Lasky JA, Lynch DA, Ryu JH, Swigris JJ, Wells AU, Ancochea J, Bouros D, Carvalho C, Costabel U, Ebina M, Hansell DM, Johkoh T, Kim DS, King TE, Kondoh Y, Myers J, Muller NL, Nicholson AG, Richeldi L, Selman M, Dudden RF, Griss BS, Protzko SL, Schunemann HJ (2011) An official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT statement: idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: evidence-based guidelines for diagnosis and management. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 183:788–824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.King TE Jr, Pardo A, Selman M (2011) Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Lancet 378:1949–1961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bonner JC (2004) Regulation of PDGF and its receptors in fibrotic diseases. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 15:255–273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Inoue Y, King TE Jr, Barker E, Daniloff E, Newman LS (2002) Basic fibroblast growth factor and its receptors in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 166:765–773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Khalil N, O’Connor RN, Unruh HW, Warren PW, Flanders KC, Kemp A, Bereznay OH, Greenberg AH (1991) Increased production and immunohistochemical localization of transforming growth factor-beta in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 5:155–162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hilberg F, Roth GJ, Krssak M, Kautschitsch S, Sommergruber W, Tontsch-Grunt U, Garin-Chesa P, Bader G, Zoephel A, Quant J, Heckel A, Rettig WJ (2008) BIBF 1120: triple angiokinase inhibitor with sustained receptor blockade and good antitumor efficacy. Cancer Res 68:4774–4782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hostettler KE, Zhong J, Papakonstantinou E, Karakiulakis G, Tamm M, Seidel P, Sun Q, Mandal J, Lardinois D, Lambers C, Roth M (2014) Anti-fibrotic effects of nintedanib in lung fibroblasts derived from patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respir Res 15:157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wollin L, Maillet I, Quesniaux V, Holweg A, Ryffel B (2014) Antifibrotic and anti-inflammatory activity of the tyrosine kinase inhibitor nintedanib in experimental models of lung fibrosis. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 349:209–220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wollin L (2015) Mode of action of nintedanib in the treatment of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Eur Respir J 45:1434–1445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crino L, Metro G (2014) Therapeutic options targeting angiogenesis in nonsmall cell lung cancer. Eur Respir Rev 23:79–91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Renzoni EA (2004) Neovascularization in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: too much or too little? Am J Respir Crit Care Med 169:1179–1180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ford NL, Martin EL, Lewis JF, Veldhuizen RA, Holdsworth DW, Drangova M (2009) Quantifying lung morphology with respiratory-gated micro-CT in a murine model of emphysema. Phys Med Biol 54:2121–2130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Artaechevarria X, Blanco D, Pérez-Martín D, de Biurrun G, Montuenga LM, de Torres JP, Zulueta JJ, Bastarrika G, Muñoz-Barrutia A, Ortiz-de-Solorzano C (2010) Longitudinal study of a mouse model of chronic pulmonary inflammation using breath hold gated micro-CT. Eur Radiol 20:2600–2608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hübner RH, Gitter W, El Mokhtari NE, Mathiak M, Both M, Bolte H, Freitag-Wolf S, Bewig B (2008) Standardized quantification of pulmonary fibrosis in histological samples. Biotechniques 44:507–517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Richeldi L, du Bois RM, Raghu G, Azuma A, Brown KK, Costabel U, Cottin V, Flaherty KR, Hansell DM, Inoue Y, Kim DS, Kolb M, Nicholson AG, Noble PW, Selman M, Taniguchi H, Brun M, Le Maulf F, Girard M, Stowasser S, Schlenker-Herceg R, Disse B, Collard HR (2014) INPULSIS Trial Investigators: efficacy and safety of nintedanib in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med 370:2071–2082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Richeldi L, Costabel U, Selman M, Kim DS, Hansell DM, Nicholson AG, Brown KK, Flaherty KR, Noble PW, Raghu G, Brun M, Gupta A, Juhel N, Klüglich M, du Bois RM (2011) Efficacy of a tyrosine kinase inhibitor in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med 365:1079–1087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moeller A, Ask K, Warburton D, Gauldie J, Kolb M (2008) The bleomycin animal model: a useful tool to investigate treatment options for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis? Int J Biochem Cell Biol 40:362–382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Izbicki G, Segel MJ, Christensen TG, Conner MW, Breuer R (2002) Time course of bleomycin-induced lung fibrosis. Int J Exp Pathol 83:111–119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wynn TA, Barron L (2010) Macrophages: master regulators of inflammation and fibrosis. Semin Liver Dis 30:245–257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pechkovsky DV, Prasse A, Kollert F, Engel KM, Dentler J, Luttmann W, Friedrich K, Müller-Quernheim J, Zissel G (2010) Alternatively activated alveolar macrophages in pulmonary fibrosis-mediator production and intracellular signal transduction. Clin Immunol 137:89–101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schupp JC, Binder H, Jäger B, Cillis G, Zissel G, Müller-Quernheim J, Prasse A (2015) Macrophage activation in acute exacerbation of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. PLoS ONE 10:e0116775. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0116775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chamoto K, Gibney BC, Ackermann M, Lee GS, Konerding MA, Tsuda A, Mentzer SJ (2013) Alveolar epithelial dynamics in postpneumonectomy lung growth. Anat Rec (Hoboken) 296:495–503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chamoto K, Gibney BC, Ackermann M, Lee GS, Lin M, Konerding MA, Tsuda A, Mentzer SJ (2012) Alveolar macrophage dynamics in murine lung regeneration. J Cell Physiol 227:3208–3215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Roth GJ, Binder R, Colbatzky F, Dallinger C, Schlenker-Herceg R, Hilberg F, Wollin SL, Kaiser R (2015) Nintedanib: from discovery to the clinic. J Med Chem 58:1053–1063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hellberg C, Ostman A, Heldin CH (2010) PDGF and vessel maturation. Recent Results Cancer Res 180:103–114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grimminger F, Günther A, Vancheri C (2015) The role of tyrosine kinases in the pathogenesis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Eur Respir J 45:1426–1433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Costabel U, Inoue Y, Richeldi L, Collard HR, Tschoepe I, Stowasser S, Azuma A (2016) Efficacy of nintedanib in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis across prespecified subgroups in INPULSIS. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 193:178–185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ueha S, Shand FH, Matsushima K (2012) Cellular and molecular mechanisms of chronic inflammation-associated organ fibrosis. Front Immunol 3:71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Strieter RM (2008) What differentiates normal lung repair and fibrosis? Inflammation, resolution of repair, and fibrosis. Proc Am Thorac Soc 5:305–310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mentzer SJ, Konerding MA (2014) Intussusceptive angiogenesis: expansion and remodeling of microvascular networks. Angiogenesis 17:499–509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ackermann M, Tsuda A, Secomb TW, Mentzer SJ, Konerding MA (2013) Intussusceptive remodeling of vascular branch angles in chemically-induced murine colitis. Microvasc Res 87:75–82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ackermann M, Morse BA, Delventhal V, Carvajal IM, Konerding MA (2012) Anti-VEGFR2 and anti-IGF-1R-Adnectins inhibit Ewing’s sarcoma A673-xenograft growth and normalize tumor vascular architecture. Angiogenesis 15:685–695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ackermann M, Houdek JP, Gibney BC, Ysasi A, Wagner W, Belle J, Schittny JC, Enzmann F, Tsuda A, Mentzer SJ, Konerding MA (2014) Sprouting and intussusceptive angiogenesis in postpneumonectomy lung growth: mechanisms of alveolar neovascularization. Angiogenesis 17:541–551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Smadja DM, Mauge L, Nunes H, d’Audigier C, Juvin K, Borie R, Carton Z, Bertil S, Blanchard A, Crestani B, Valeyre D, Gaussem P, Israel-Biet D (2013) Imbalance of circulating endothelial cells and progenitors in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Angiogenesis 16:147–157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.de García de Alba C, Buendia-Roldán I, Salgado A, Becerril C, Ramírez R, González Y, Checa M, Navarro C, Ruiz V, Pardo A, Selman M (2015) Fibrocytes contribute to inflammation and fibrosis in chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis through paracrine effects. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 191:427–436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schraufnagel DE, Mehta D, Harshbarger R, Treviranus K, Wang NS (1986) Capillary remodeling in bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Pathol 125:97–106 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hashimoto N, Phan SH, Imaizumi K, Matsuo M, Nakashima H, Kawabe T, Shimokata K, Hasegawa Y (2010) Endothelial-mesenchymal transition in bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 43:161–172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.